Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Activity Schedules Gened wk11

Transféré par

api-360057284Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Activity Schedules Gened wk11

Transféré par

api-360057284Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

AuimSpec 0 Dsorer

Activity

Schedules.

Refusing to transition from one activity

to the next or between steps in a sin-

gle activity can impact a student's aca-

demic progress, socialization, and

independence. Problem behaviors dur-

ing transitions can impact the effec-

tiveness of teacher instruction and dis-

rupt other students' activities. As a

result, the child with the behavior

problem may be excluded from peer

social circles. Difficulty with transi-

tions can significantly limit a student's

ability to independently complete

activities across environments

throughout the school day (e.g.,

Forest, Homer, Lewis-Palmer, & Todd,

2004; Scheuermann & Webber, 2002;

Schreibman, Whalen, & Stahmer,

2000).

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is

characterized by a qualitative impair-

ment in at least two of the three fol-

Kate, a first-grade general education ed daily routines. These outbursts are lowing areas: social interaction; com-

teacher, has a new student with very disruptive to the rest of the class, munication; and restricted repetitive

Asperger's syndrome in her classroom. and some of the other students have and stereotyped patterns of behavior,

John has a very difficult time moving begun to avoid John during classroom interests, and activities. In addition,

from one activity to the next. Often he individuals diagnosed with autism

activities. John's parents report similar

will simply refuse to transition to the demonstrate delays or abnormal func-

difficulties at home during transitions

next activity by sitting down on the tioning with onset before age 3 in

floor and not moving. Other times he or changes in his schedule. Kate needs

social interaction, language used for

will scream and physically lash out at to find some research-based strategies social communication, and/or symbolic

his peers and the teacher. Kate noticed to help John more readily accept or imaginative play (American Psychi-

that the problem behaviors usually changes in his schedule and daily atric Association, APA, 2000). Students

occur during a change in his anticipat- activities. diagnosed with ASD often struggle

16 COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Helping Students With Autism

Spectrum Disorders in General

Education Classrooms Manage

TransitionIssues

Devender R. Banda I Eric Grimmett I Stephanie L. Hart

with transitions, which may lead to al., 2000). Further, many children with support systems. Visual supports, such

problem behaviors such as verbal and ASD have difficulties with communica- as picture cues and activity schedules,

physical aggression, tantrums, noncom- tion and socialization, which may con- may help reduce or eliminate the need

pliance, and self-injury (Schreibman et tribute to problem behaviors when fac- for students to rely on adults to pro-

al., 2000). ing both routine and unexpected vide assistance and clarification during

Transition problems can be especial- schedule changes (Jamieson, 2004). To scheduled and unscheduled changes.

ly evident when children with ASD are ease transitions, adults may opt to pro- Because children with ASD typically

taught in general education settings. vide support for every change within a respond to visual input as their pri-

The Centers for Disease Control and daily schedule. However, this may mary source of information (Quill,

Prevention (2007) report that the cause children with ASD to become 1995), the use of visual support sys-

prevalence of ASD was approximately overly dependent on adult caregivers to tems can supplement verbal directions

1 in 150 children and reflects an stay on task and on schedule through- when students have deficits in auditory

increase in diagnoses and special edu- out their daily activities (Heflin & processing. In addition, children with

cation servicing of children eligible Alaimo, 2007; Scheuermann & Webber, ASD may prefer photographs of people

to the people themselves; even when

directly interacting with people, these

Difficulty with transitions can significantly limit a children tend to focus on physical fea-

student's ability to independently complete activities tures rather than attending to the per-

son as an intact entity (Heflin &

across environments throughout the school day. Alaimo, 2007).

Activity schedules are a promising

educational strategy to support transi-

under "autism" designations over the 2002). The challenge to teachers is to tions for students with autism (Scheu-

past decade. Teachers can expect to provide students with the needed sup- ermann & Webber, 2002; Wetherby &

face transition problems in the general port during transitions while decreas- Prizant, 2000). An activity schedule is

education classroom with the inclusion ing dependence on adult instructions. a visual support system that combines

of students with ASD, as a general There are several strategies for photographs, images, or drawings in a

education environment can be over- reducing transition difficulties, such as sequential format to represent a target-

whelming to these children. The many choice making, incorporating preferred ed sequence of the student's day.

different activities scheduled in a typi- activities, using behavioral momentum Activity schedules provide predictabili-

cal school day are problematic for a or high-probability strategies, and rein- ty throughout the student's day and

child whose resistance to change is an forcing appropriate transition behav- allow a student to anticipate changes

inherent component of his or her iors. One promising area of interven- in the daily routine. Providing the stu-

autism (e.g., APA, 2000; Schreibman et tion for children with ASD is visual dent with increased time to process

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN I MAR/APR 2009 17

schedules with students with ASD in

inclusive settings. In this article, we

describe steps to build activity sched-

ules for use in general education class-

rooms and provide examples and

resources for general education teach-

ers (see box, "Online Resources for

Activity Schedules"). By following the

steps in this article and consulting with

special education professionals, general

education teachers will have the skills

to use activity schedules to decrease

transition issues in their classrooms.

Building and Implementing

Activity Schedules

Step 1: Identify and Define Target

Transition Behaviors

First, collaborate with parents and

other teachers involved with the stu-

dent to identify difficult transition

times during the day or specific situa-

tions. Students with ASD may have

problems terminating an ongoing activ-

ity or beginning a new activity. For

example, a student may cry or throw

materials when cleaning up the art

center to transition to lunch, because

upcoming changes enhances the

opportunity for increased participation Activity schedules provide predictability throughout the student's

in existing routines and transitions

(Jamieson, 2004). Best of all, activity day and allow a student to anticipate changes in the daily routine.

schedules are easy to construct and

can be applied to existing routines in Although activity schedules are fre- the student wants to continue the cur-

general education classrooms with

quently used by special education rent activity. Or, students may have

minimal effort.

teachers, general education teachers trouble beginning a new activity, like

Researchers in a number of studies

can also develop and use activity reading, if they were not able to com-

have consistently found activity sched-

ules to be an effective intervention for

children with ASD (Banda & Grimmett, Online Resources for Activity Schedules

2008; see box, "What Does the Litera- http://atto.tbtffalo.edLu/r-egisteredi/ATBasics/Populations/aac/scliedules.phip

ture Say About Activity Schedules?"). This Web site is part of the Assistive Technology TrYaining Online ProJect of

Using research-based strategies not the University of Buffalo and provides an overview of different visual sup-

only enhances teacher efficiency but port systems.

also complies with the No Child Left http://www.joeschedule.cotU/

Behind Act of 2001's directive to use For a juinimral fee, this Web site can help teachers plan, construct, and

evidence-based strategies. Researchers store their activity schedules very easily. A number of free schedules and

have found that activity schedule inter- e,xamiples are also provided.

ventions can successfully reduce prob-

lhttp)://autismi.hiealinigthiresliolds.comi/Itlerapy//visual-schedules

lem behaviors during transitions and This Web site provides more basic informnation about activity schedules, as

increase daily living skills, social well as a list of pertinent references.

behavior, and social initiation in stu-

WWW.m-aylýer-.johinsoni.com

dents with ASD (Banda & Grimmett;

Mayer-Johnson is the creator of Board na ker"11, a leading Picture commnunti-

Heflin & Alaimo, 2007; Scheuermann &

cation symnbol program.

Webber, 2002).

18 COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

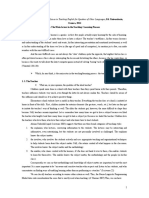

Figure 1. Example of Between-Activity Schedule

start homework spelling art reading seat work lunch recess

bathroom math math work gym snack pack up go home stop

4,2

--a

Note. Picture Communication Symbols © 1981-2008 by Mayer-Johnson LLC. All rights reserved worldwide. Used with permission.

Boardmaker® is a registered trademark of Mayer-Johnson LLC.

plete a required math worksheet. A ble completing multiple steps in a task Figure 2. Example of

problem behavior may also occur analysis-for example, a student who Within-Activity Schedule

when a schedule is changed, even if writes her name on the paper but does

the new activity is as desirable as the not begin the assignment-may need a

missed activity, such as a student who within-activity schedule (see Figure 2).

becomes upset when it rains and A within-in activity schedule shows the

recess must be held inside. steps of a single activity in order.

Next, specifically describe the prob-

lem behavior. For example, "When Step 4: Choose a Mode of

Presentation

Susie is asked to line up for lunch, she

often screams 'No!' and hits the stu- Activity schedules can take a number

dent next to her." This clearly defines of forms, all of which can be construct-

the problem behavior so that any ed using items in the classroom. The

observer could identify how it relates most common mode of presentation is

to transition issues. a simple notebook with one picture

attached to each page (Bryan & Gast,

Step 2: Collect Baseline Data on 2000; Dettmer, Simpson, Myles, &

the Problem Behavior Ganz, 2000). Activity schedules can

Before introducing the activity sched- also be constructed on a sentence strip

ule intervention, collect data on the by attaching Velcro and sequencing

frequency or duration of problem pictures. For high-functioning students

behaviors (e.g., refusal to complete an in primary grades, a teacher might use

activity, whining, refusal to begin an multiple pictures on each page with

activity) for 2 to 3 days to establish word labels under each picture to facil-

baseline (preintervention) data. By col- itate reading skills; higher functioning

lecting baseline data, the teacher can students in later grades can generate

determine an average frequency or their own written schedules. If the

duration of behavior(s) before intro- notebook is small, the student can take

ducing the activity schedule interven- it from class to class to provide support

tion. For dangerous or harmful behav- throughout the day.

iors, the intervention can be imple- Step 5: Choose a Medium for

mented without collecting baseline

the Activity Schedule

data to avoid delaying treatment.

Activity-schedule pictures can be line

Step 3: Choose a Between-Activity drawings, photos, or even lightweight

or Within-Activity Schedule objects. Pictures should be fairly sim-

There are two types of activity sched- ple and straightforward (see Figures 1

ules: between-activity and within-activ- and 2), such as a photograph of art

Note. Picture Communication Symbols

ity. A between-activity schedule (see supplies to represent art class, and are

© 1981-2008 by Mayer-Johnson LLC.

Figure 1) shows each activity of the readily available from commercial soft- All rights reserved worldwide. Used with

day in order and may list the time for ware (e.g., Boardmaker®, Mayer permission. Boardmaker® is a trademark

each activity. Students who have trou- Johnson). Pictures should be selected of Mayer-Johnson LLC.

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN I MAR/APR 2009 19

based on the student's abilities; for a direct the child to the activity schedule. respond to a classwide request to begin

student with limited cognitive abilities, After the completion of each activity, the next activity, individually address

select miniature objects (e.g., small use verbal or physical prompts as nec- the student and announce the next

ball for play) or photographs of the essary to help the student remove the activity. This type of cue will help the

student performing different activities. picture of the completed activity, put child focus on the next activity rather

For higher functioning students, use the picture in the finished pocket/ than allowing his refusal to escalate

abstract representations, such as clip basket, and begin the next activity on into a tantrum. Gradually provide

art, line drawings, or words. The ulti- the schedule. Then give praise for com- fewer physical and verbal prompts

mate goal of the activity schedule is to pleting the activity and direct the stu- until the student is able to independ-

increase independent transitions with- dent towards the next activity or step ently complete an activity, check the

in and between activities and decrease of an activity on the schedule. (For stu- schedule, move the activity picture

problem behaviors during transition dents using portable notebooks, model from the schedule to "finished" box,

times (Bryan & Gast, 2000; Dettmer et how to cross each step or activity off and transition to the next activity. For

al., 2000; Dooley, Wilczenski, & the list after it is completed.) higher functioning students or those

Torem, 2001; Massey & Wheeler, using portable notebooks, independent

2000). Step 8: Collect Intervention Data use of an activity schedule should

Continue to collect data while using require minimal verbal or nonverbal

Step 6: Choose a Location for the activity schedule to determine if adult prompts, such as a gesture

the Schedule problem behaviors are decreasing from towards the notebook.

Attach the schedule someplace that is baseline levels. Monitor data regularly

familiar to the child and easy to see to determine the effectiveness of the Step 11: Fade the Prominence

(e.g., desk, wall, cabinet). Label the activity schedule strategy. The child of the Activity Schedule

activity schedule with the child's should begin to use the schedule more This step is intended to make the

name; have some type of container independently and display fewer prob- schedule both socially and age appro-

(e.g., envelope, basket, box) to hold lem behaviors during transitions. If the priate. Move the schedule from the

completed activity pictures. Label each strategy is not working, retrain the stu- wall into a binder and discontinue

using Velcro. Put all of the pictures intD

a one-page document and have the stu-

The ultimate goal of the activity schedule is to increase dent check or cross off each item as it

is completed. Shrink the size of the

independent transitions within and between activities and pictures and increase the size of the

decrease problem behaviors during transition times. words until the schedule uses words

only. When the student no longer

activity in words (e.g., lunch) to pro- dent using the procedure outlined in needs to physically check off each

mote literacy skills and reduce depend- Step 7. item, remove the binder. The schedule

ency on pictures. Tell the student that can be laminated and attached to the

the schedule will show him/her what Step 9: Add New Pictures student's desk.

to do next throughout the day. For stu- or Words Finally, shrink the size of the text,

dents with portable notebooks, talk When the student is able to transition print, and laminate the schedule so

with the student to plan where to keep within or between selected activities, that it can be folded to fit in a wallet cr

the notebook (e.g., desk or backpack) even with prompts, extend the use of purse. At this point, the schedule is

during each activity or class. Pages the activity schedule to cover a longer essentially a list of activities. "Pocket"

from written activity schedules can be period of time within the same setting schedules can be continued into the

placed into protective plastic sheets so or subject. For example, if a student teenage and adult years.

that the student can use an overhead uses an activity schedule to complete

or dry erase marker to cross off com- an independent writing activity, add Step 12: Promote Generalization

pleted steps each day. steps to guide the student to complete Across Activities and Settings

the subsequent small-group writing Apply activity schedules to transitions

Step 7: Train the Student to Use activity. This way, more pictures or in as many settings as possible. As the

the Activity Schedule words can be added as the student student learns to use the activity

Training the student to use the activity begins using the activity schedules schedule, steps for additional activities

schedule is an important step. The independently. may be added to increase the student'3

majority of successful interventions uti- level of independence. For example,

lizing activity schedules use some type Step 10: Fade Prompts being able to complete a sequence of

of training through modeling and/or As a student becomes more independ- "name on paper, color, cut, glue, and

prompting (Banda & Grimmett, 2008). ent in the use of the schedule, reduce turn in" to complete a vocabulary

During the training period, routinely prompting. If a student does not worksheet suggests the student may be

20 COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

The strength of activity schedules is the ease in which with autism to use photographic activity

schedules: Maintenance and generaliza-

they can be planned, constructed, and incorporated into tion of complex response chains. Journal

of Applied BehaviorAnalysis, 26, 89-97.

existing activities across a number of settings. Massey, N. G., & Wheeler, J. J. (2000).

Acquisition and generalization of activity

ready to use an activity schedule to fol- Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, schedules and their effects on task man-

553-567. agement in a young child with autism in

low steps in a math activity. The

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention an inclusive pre-school classroom. Educa-

strength of activity schedules is the tion and RTaining in Mental Retardation

(2007, February 9). CDC releases new

ease in which they can be planned, data on autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and Developmental Disabilities,35,

constructed, and incorporated into from multiple communities in the United 326-335.

existing activities across a number of States [Press release]. Retrieved February Morrison, R. S., Sainato, D. M., Bencha-

22, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/od/ aban, D., & Endo, S. (2002). Increasing

settings, Following initial training, chil-

oc/media/pressrel/2007/rOt7O208.htm play skills of children with autism using

dren with ASD can use activity sched- Dauphin, M., Kinney, E. M., & Stromer, R. activity schedules and correspondence

ules to independently complete com- (2004). Using video-enhanced activity training. Journal of Early Intervention,

plex tasks and remain engaged in a schedules and matrix training to teach 25, 58-72.

variety of settings and situations sociodramatic play to a child with Pierce, K. L., & Schreibman, L. (1994).

autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Teaching daily living skills to children

(MacDuff, Krantz, & McClannahan, Interventions, 6, 238-250. with autism in unsupervised settings

1993). Home-based activity schedules Dettmer, S., Simpson, R. L., Myles, B. S., & through pictorial self-management.

may be implemented to increase partic- Ganz, J. B. (2000). The use of visual sup- Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27,

ipation in leisure activities, social inter- ports to facilitate transitions of students

471-481.

with autism. Focus on Autism and Other

action, self-care, and housekeeping Quill, K. A. (1995). Visually cued instruc-

Developmental Disabilities,15, 163-169.

tasks (Krantz, MacDuff, & McClan- tion for children with autism and perva-

Dooley, P., Wilczenski, F. L., & Totem, C.

sive developmental disorders. Focus on

nahan, 1993). (2001). Using an activity schedule to

smooth school transitions. Journal of Autistic Behavior, 10, 10-20.

Final Thoughts Positive Behavior Interventions, 3, 57-61. Scheuermann, B., & Webber, J. (2002).

Forest, E. J., Homer, R. H., Lewis-Palmer, T., Autism: Teaching DOES make a differ-

Activity schedules have been shown to ence. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth-Thomson

& Todd, A. W. (2004). Transitions for

be effective interventions for students young children with autism from pre- Learning.

with ASD, and can be considered an school to kindergarten. Journalof Schreibman, L., Whalen, C., & Stahmer, A.

evidence-based teaching strategy that Positive Behavior Interactions, 6, 103-112. (2000). The use of video priming to

Hall, L. J., McClannahan, L. E., & Krantz, P. reduce disruptive transition behavior in

may help students transition more easi-

J. (1995). Promoting independence in children with autism. Journal of Positive

ly between scheduled routines and integrated classrooms by teaching aides Behavior Interventions, 2, 3-11.

activities. Activity schedules also have to use activity schedules and decreased Watanabe, M., & Sturmey, P. (2003). The

shown promise in teaching on-task prompts. Education and TRaining in effect of choice-making opportunities

behaviors and can serve as a valuable Mental Retardation and Developmental during activity schedules on task engage-

Disabilities,30, 208-217. ment of adults with autism. Journal of

support in helping students with ASD Heflin, L. J., & Alaimo, D. F. (2007). Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33,

manage the multiple tasks typically Students with autism spectrum disorders: 535-538.

found in inclusive settings. By follow- Effective instructionalpractices. Upper Wetherby, A. M., & Prizant, B. M. (2000).

ing the steps presented in this article, Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. Autism spectrum disorders: A transaction-

Jamieson, S. (2004). Creating an education- al developmental perspective. Baltimore:

general education teachers can plan

al program for young children who are Paul H. Brookes.

and construct activity schedules to blind and who have autism. RE:view, 35,

meet the needs of individual students 165-177.

Devender R. Banda (CEC TX Federation),

with ASD. Krantz, P. J., MacDuff, M. T., & McClan-

Assistant Professor of Special Education;

nahan, L. E. (1993). Programming partic-

Eric Grimmett (CEC TX Federation),

References ipation in family activities for children

with autism: Parents' use of photographic Doctoral Student in Special Education;

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). and Stephanie L. Hart (CEC TX Federa-

activity schedules. Journal of Applied

Diagnosticand statistical manual of men- Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 137-138. tion), Doctoral Student in Special Education,

tal disorders (4th ed. rev.). Washington, College of Education, Texas Tech University,

Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1993).

DC: Author. Teaching children with autism to initiate Lubbock.

Banda, D. R., & Grimmett, E. (2008). to peers: Effects of script-fading proce-

Enhancing social and transition behav- dure. Journalof Applied Behavior Address correspondence to Devender R.

iors of persons with autism through Analysis, 26, 121-132. Banda, College of Education, Texas Tech

activity schedules: A review. Education Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1998). University, Box 41071, Lubbock, TX 79409-

and TRaining in Developmental Social interaction skills for children with 41071 (e-mail: Devender.banda@tta.edu).

Disabilities,43, 324-333. autism: A script-fading procedure for

Bryan, L. C., & Gast, D. L. (2000). Teaching beginning readers. Journal of Applied TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 41,

on-task and on-schedule behaviors to Behavior Analysis, 31, 191-202. No. 4, pp. 16-21.

high-functioning children with autism via MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClan-

picture activity schedules. Journalof nahan, L. E. (1993). Teaching children Copyright 2009 CEC.

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN I MAR/APR 2009 21

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

TITLE: Activity Schedules: Helping Students with Autuism

Spectrum Disorders in General Education Classes Manage

Transition Issues

SOURCE: Teach Except Child 41 no4 Mr/Ap 2009

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it

is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in

violation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher:

http://www.cec.sped.org/

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Eric Soulsby Assessment Notes PDFDocument143 pagesEric Soulsby Assessment Notes PDFSaifizi SaidonPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Near-Death Experiences - Understanding Visions of The Afterlife (PDFDrive) PDFDocument209 pagesNear-Death Experiences - Understanding Visions of The Afterlife (PDFDrive) PDFSandarePas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Performance Report PDFDocument76 pagesPerformance Report PDFBenny fernandesPas encore d'évaluation

- MBA Assignment ExampleDocument21 pagesMBA Assignment ExampleZamo Mkhwanazi75% (4)

- Practical Research 2: Quarter 1 - Module 4A: Creation of Conceptual FrameworkDocument23 pagesPractical Research 2: Quarter 1 - Module 4A: Creation of Conceptual FrameworkRaylyn Heart Roy50% (4)

- Learning in A Visual AgeDocument16 pagesLearning in A Visual Ageapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum DesignDocument30 pagesCurriculum DesignDianne Bernadeth Cos-agonPas encore d'évaluation

- Masculine and Feminine QualitiesDocument2 pagesMasculine and Feminine QualitiesJashishPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Vocabulary in Use AdvancedDocument6 pagesBusiness Vocabulary in Use AdvancedMadina Abdresheva100% (1)

- Teaching Methodologies in TESOL: PPP vs. TBLDocument11 pagesTeaching Methodologies in TESOL: PPP vs. TBLMarta100% (10)

- Classroom ManagementDocument201 pagesClassroom ManagementMuhammad Sarmad AnwaarPas encore d'évaluation

- DidacticaDocument74 pagesDidacticaIon Viorel100% (1)

- Adhd School Support List wk6Document7 pagesAdhd School Support List wk6api-365463992Pas encore d'évaluation

- Increasing Behavior Specific Praise EbdDocument12 pagesIncreasing Behavior Specific Praise Ebdapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edi 685 Action Research SummaryDocument1 pageEdi 685 Action Research Summaryapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edi 685 Unit PlanDocument54 pagesEdi 685 Unit Planapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Choice Making To Elementary Students With DisabilitiesDocument7 pagesTeaching Choice Making To Elementary Students With Disabilitiesapi-365463992Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edi 685 Action Research ProjectDocument7 pagesEdi 685 Action Research Projectapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edi 685 Quiet Choice Activity Shelf PresentationDocument9 pagesEdi 685 Quiet Choice Activity Shelf Presentationapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edi 685 Observation 2 Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesEdi 685 Observation 2 Lesson Planapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edi 638 Classroom Environment Plan Paper-No DateDocument9 pagesEdi 638 Classroom Environment Plan Paper-No Dateapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aep Wire CatterallDocument3 pagesAep Wire Catterallapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching ResumeDocument2 pagesTeaching Resumeapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- UntitleddocumentDocument9 pagesUntitleddocumentapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Learning To LookDocument5 pagesLearning To Lookapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Socioemotional Benefits of The Arts SummaryDocument18 pagesSocioemotional Benefits of The Arts Summaryapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Maeia Va StandardsDocument2 pagesMaeia Va Standardsapi-360057284Pas encore d'évaluation

- Visual Arts at A Glance - New Copyright InfoDocument8 pagesVisual Arts at A Glance - New Copyright Infoapi-340384877Pas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated-Infant 20toddler 20curriculum 20motor 20developmentDocument2 pagesAnnotated-Infant 20toddler 20curriculum 20motor 20developmentapi-623069948Pas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Development Chapter 5Document53 pagesPersonal Development Chapter 5Edilene Rosallosa CruzatPas encore d'évaluation

- M.A. I II Psychology SyllabusDocument14 pagesM.A. I II Psychology SyllabusArunodaya Tripathi ArunPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of The Related LiteratureDocument8 pagesReview of The Related LiteratureNethel Clarice D. Durana40% (5)

- Chapter 1.1 Intro PsyDocument27 pagesChapter 1.1 Intro PsyFatimah EarhartPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychological Testing - PPT (Joshua Pastoral & Camille Organis)Document15 pagesPsychological Testing - PPT (Joshua Pastoral & Camille Organis)Allysa Marie BorladoPas encore d'évaluation

- Power of The SoulDocument311 pagesPower of The Soulmartafs-1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cape 2006 Comm p2 Sec BDocument2 pagesCape 2006 Comm p2 Sec Bsanjay ramsaran50% (2)

- Psychological Perspective of The SelfDocument9 pagesPsychological Perspective of The SelfJes DonadilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Mary Kiriakidis - Final Position Paper FinalDocument13 pagesMary Kiriakidis - Final Position Paper Finalapi-682308329Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson-Exemplar English9 Melc-1Document5 pagesLesson-Exemplar English9 Melc-1Pethy DecendarioPas encore d'évaluation

- It's Good To Blow Your Top: Women's Magazines and A Discourse of Discontent 1945-1965 PDFDocument34 pagesIt's Good To Blow Your Top: Women's Magazines and A Discourse of Discontent 1945-1965 PDFRenge YangtzPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychoanalytic Theory by Sigmund FreudDocument23 pagesPsychoanalytic Theory by Sigmund FreudYongPas encore d'évaluation

- A. Ideational LearningDocument2 pagesA. Ideational LearningSherish Millen CadayPas encore d'évaluation

- HUMSS PRACTICAL RESEARCH PRDocument37 pagesHUMSS PRACTICAL RESEARCH PRyuanaaerith13Pas encore d'évaluation

- $R0ACKNFDocument7 pages$R0ACKNFjessi NchPas encore d'évaluation

- Module - Principles of Teaching 2Document11 pagesModule - Principles of Teaching 2noreen agripa78% (9)

- Tracey Anderson West Georgia University Assignment 1: Introduction & Research QuestionDocument7 pagesTracey Anderson West Georgia University Assignment 1: Introduction & Research Questionapi-336457857Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment No. 1 Principle and Theories of Language Acquisition and Learning - PRELIMDocument4 pagesAssignment No. 1 Principle and Theories of Language Acquisition and Learning - PRELIMLes SircPas encore d'évaluation