Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Endocarditis Review

Transféré par

Catherine Saenz SerranoCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Endocarditis Review

Transféré par

Catherine Saenz SerranoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mædica - a Journal of Clinical Medicine

S TATE - OF - THE - ART

Endocarditis in the 21st Century

Monica Mariana BALUTAa; Elisabeta Otilia BENEAb; Cristina Maria STANESCUc;

Marius Marcian VINTILAa

a

”Carol Davila” University of Medicine, Cardiology Department “St Pantelimon”

Hospital, Bucharest, Romania

b

“Carol Davila” University of Medicine, National Institute of Infectious Diseases

“Prof. Dr. Matei Bals”, Bucharest, Romania

c

”Carol Davila” University of Medicine, Cardiology Department Colentina Hospital,

Bucharest, Romania

I undersign, Monica Mariana Baluta, certificate that I do not have any financial or

personal relationships that might bias the content of this work.

ABSTRACT

Endocarditis still carries a poor prognosis despite improvement in preventive strategies and advances

in diagnosis and also in treatment. Epidemiology of infective endocarditis (IE) has changed in late years.

Contemporary antibiotic overuse determines antibiotic resistance against microorganisms involved in

IE. Prophylaxis principles have been changed and restricted in order to avoid excessive antibiotic use and

unfounded costs. Current guidelines are often based on expert opinion because of the low incidence of the

disease, the absence of randomized trials, and the limited number of meta-analyses. The present review

will focus on current changes in epidemiology, prophylaxis, diagnosis and treatment options.

Keywords: infective endocarditis, epidemiology, prophylaxis, treatment options

INTRODUCTION Current definition and classification

I

nfective endocarditis (IE) is a syndrome IE represents an infection of the endocardial

that is permanently changing, with new surface of the heart, including large intratho-

high risk patients and new microorgan- racic vessels and intracardiac foreign bodies,

isms, with more intracardiac device infec- microorganisms being present in the character-

tions, with intravenous drug abusers, and istic lesion. IE is a syndrome rather than a dis-

increasing nosocomial infections. ease, diagnosis being established on many find-

Development of preventive strategies and ings.

diagnostic procedures and advances in treat- The old term bacterial endocarditis has

ment are not enough to improve the poor been replaced with the term infective endocar-

prognosis due to elevated mortality. ditis (1). Bacterial endocarditis was an inappro-

Address for correspondence:

Monica Baluta MD, PhD. Office Address: “St Pantelimon” Hospital, 340 Soseaua Pantelimon, zipcode 21659, Bucharest 2, Romania.

e-mail: monicabaluta@yahoo.com

290 Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011

ENDOCARDITIS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

priate term ignoring the nonbacterial forms of 5) new at-risk groups has emerged, including

IE (2). Of historical relevance is also the classifi- intravenous drug users, patients with intracar-

cation in acute and subacute IE. The current diac devices, and those exposed to healthcare

terms and classification endorsed by ESC were associated bacteriemia (e.g., intravenous cath-

updated in the last guideline and are exposed eters).

in Table 1 (3). Male sex appears to be more frequent in-

volved than female in all epidemiological stud-

Epidemiological modification ies, with a male: female ratio that can exceed

2:1 with a range of 1 to 3:1 in 18 large series.

The incidence of infective endocarditis var-

Despite increased male incidence, female are

ies between countries because the criteria for

prone to an altered prognosis (6).

diagnosis and the methods of reporting vary

with different series determining a lack of uni-

Current infectious etiology

formity in registering the disease.

The reported incidence is 3-10 episodes/ Streptococci and staphylococci remain re-

100,000 person/year (4,5). The mean age of sponsive for the majorities of cases with identi-

patients with IE has gradually increased in the fied microbiology. Streptococci are common in

antibiotic era. The incidence of IE decreases in NVE and late PVE, Staphylococcus aureus and

young patients in present days, but increased Coagulase-negative staphylococci being domi-

abruptly with age, with a peak incidence of nant in early PVE, and tricuspid valve S. aureus

14.5 episodes/100,000 person/year between infection in IV drug abusers (Table 2) (7).

70-80 years of age (3). Culture-negative endocarditis remain a pro-

Many factors are related to this shift in age blem and may be due to a number of factors:

distribution: 1) the age of the population has 1) cultures taken toward the end of a chronic

been increasing steadily; 2) people with rheu- course (>3 months), 2) slow growth of fastidi-

matic or congenital heart disease are surviving ous organisms (anaerobes, Haemophilus spp.,

longer 3) the underlying heart disease change Actinobacillus spp., Cardiobacterium spp., or

etiology-elderly characteristic degenerative he- Brucella spp.), 3) fungal IE; 4) IE caused by in-

art disease took place of rheumatic heart disea- tracellular parasites (rickettsiae, chlamydiae, T.

se; 4) more frequent prosthetic valve surgery; whippelii, possibly viruses), 5) uremia superve-

Definite

Based on fulfilling of

Suspected

current diagnosis criteria

Possible

Left-sided IE:

- native valve endocarditis (NVE)

- prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE)

Cardiac

Related to anatomical site 1. early PVE (<1 year after valve surgery)

2. late PVE (>1 year after valve surgery)

Right-sided IE

Device related IE pacemaker, cardioverter/defibrilator

Community acquired

Acquisition mode Health care associated: Nosocomial/ Non-nosocomial

Intravenous drug abuse-

associated IE

another episode of IE caused by the same microorganism <6

Relapse

month following first episode

Related to recurrence

another episode of IE caused by the other microorganism >6

Reinfection

month following first episode

persistent infection in blood and/or in pathogenic lesion, or

Active IE

Related to disease activity patient under antibiotic therapy

Healed IE refer to cured IE

IE with positive blood cultures

Based on the etiologic agent IE with negative blood cultures because of prior antibiotic treatment

responsible IE frequently associated with negative blood cultures

IE associated with constantly negative blood cultures

TABLE 1. Classification and definitions of infective endocarditis

Adapted from reference (3)

Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011 291

ENDOCARDITIS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

ning in a chronic course; 6) mural thrombi IE, blood or from cardiac tissue; (2) phenotypic

as in post–myocardial infarction, or infection identification of the isolates after the culture re-

related to pacemaker wires, 7) noninfective sults; (3) molecular identification methods: nu-

Libman-Sacks endocarditis or, 8) an incorrect cleic acid target, signal amplification, and/or

diagnosis. sequence analysis that give a specific and fast

A proper collection of blood culture speci- alternative to the previous methods. Molecular

mens together with care in the performance of methods provide now the best tools for detec-

serologic tests, and use of newer diagnostic tec- tion in those cases where the culture of respon-

hniques may reduce the proportion of culture- sible microorganism is difficult or impossible to

negative cases (8). obtain in case of fastidious germs and prior an-

timicrobial treatment. PCR (polymerase chain

DIAGNOSIS reaction) permit a rapid and reliable recogni-

tion of fastidious and non-culturable agents (8,

S ince Osler’s clinical diagnosis based on the

classical signs, infective endocarditis diagno-

sis has improved today by using microbiologi-

11,12).

A minimum of 3 blood culture sets (no more

cal tests and echocardiography (10). than two bottles per venipuncture) must be ob-

1) Clinical diagnosis tained in the first 24 hours of admission (3). At

Clinical features (Table 3) may present as an least 2 separate sets of blood cultures taken 30

acute, rapidly progressive infection, but the dis- min apart by separate venipunctures should be

ease usually runs a subacute evolution with obtained within the first 1-2 hours of presenta-

multiple nonspecifics, confusing symptoms. tion. Positive blood culture represents a major

2) Microbiological diagnosis criteria for IE diagnosis and it is defined as the

Identifying the offender microorganism is following:

one of the most important tests for diagnosis of • 2 separate positive blood cultures (BC),

IE at this time and can be done using: (1) the in the absence of a primary focus, with

culture of viable microorganisms from the typical microorganisms related to IE (Vi-

Endocarditis

Agent Early PVE <12 months (%) Late PVE > 12 months (%)

all type (%)

60–80

Streptococci 2 28

(30–40 Viridans)

Staphylococci 20–35 25 (S Aureus) 17 (S Aureus)

Coagulase-positive 10–27 25 (S Aureus) 17 (S Aureus)

Coagulase-negative 1–3 29 12

Enterococci 5–18 10 14

Gram-negative aerobic bacilli 1.5–13 13 5

Fungi 2–4 7 2

Culture-negative <5–24 8 9

Polymicrobial Rare 2 5

Diphtheroids NA 3 2

Coxiella burnetii NA - 2

TABLE 2. Etiologic agents in infective endocarditis

PVE - prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Adapted from references (2,9)

Symptoms Patients (%) Signs Patients (%)

Fever 80 Fever 90

Chills 40 Heart murmur 85

Weakness 40 Changing murmur 5–10

Dyspnea 40 New murmur 3–5

Weight loss 25 Embolic phenomenon >50

Cough 25 Skin manifestations 18–50

Skin lesions 20 Osler nodes 10–23

Stroke 20 Splinter hemorrhages 15

Nausea/vomiting 20 Petechiae 20–40

Headache 20 Janeway lesion <10

Myalgia/arthralgia 15 Splenomegaly 20–57

Delirium/coma 10–15 Septic complications 20

Hemoptysis 10 Mycotic aneurysms 20

TABLE 3. Clinical manifestations of infective endocarditis

292 Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011

ENDOCARDITIS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

ridans streptococci, Streptococcus bovis, cally treated patient with suspected complica-

HACEK group, Staphylococcus aureus; tion (class I- ESC recommendation) or without

community-acquired enterococci) (3) suspected complication (class IIa -ESC) as well

• persistently positive BC with microorga- as for evaluation of cardiac and valve morphol-

nisms consistent with IE defined as: 1) at ogy and function at completion of antibiotic

least 2 positive cultures of blood samples therapy.

drawn >12 h apart; or 2) all 3 or a ma- Transoesophageal echocardiography

jority of ≥ 4 separate BC (with first and

TEE is recommended for diagnosis in high

last sample drawn at least 1 h apart) (3)

suspicion cases with negative TTE, can be re-

• single positive BC for Coxiella burnetii or

antiphase I IgG antibody titer >1:800 (3) peated at 7-10 days if initially negative and

3) Echocardiography high IE suspicion persist, and is not indicated

Transthoracic and transoesophageal echo- when TTE is frankly negative in low suspicion

cardiography (TTE/TEE) identify de characteris- patient (class III-ESC). Expert’s opinion is that

tics lesion: the vegetation, abscesses, pseudoa- TEE should be used in the majority of patients

neurysm, perforation, fistula, valve aneurysm, with suspected IE (class IIa- ESC). For the follow

and dehiscence of a prosthetic heart valve (13, up of medically treated patient TEE have same

14). indication as TTE.

The sensitivity of TTE is acceptable (40 to Echocardiography provides the evidence

63%) and that of TEE is very good (90 to 100%) for endocardial involvement, the other major

(15). According to new European guideline, criteria in current revised diagnosis criteria (3,

echocardiography is recommended: for diag- 17,18).

nostic purposes and follow-up of the therapy,

4) Criteria for diagnosis

intra-operatively, and following completion of

Longtime used Duke criteria of IE were re-

therapy (3,16).

Transthoracic echocardiography vised over the time and amended by some of Li

TTE is the first line imaging tool for diagnosis recommendation and are exposed simplified

in suspected IE. If TTE is initially negative and IE in Table 4 (3,17,18). Those criteria used in pre-

suspicion persists, it can be repeated at 7-10 vious epidemiological studies have a high sen-

days. If good quality negative TTE is obtained sitivity and specificity for the diagnosis but they

in case of low suspicion, no TEE is indicated. do not replace clinical judgment, especially in

TTE should be used for follow up of the medi- the setting of new forms of IE.

Definite IE Possible IE Rejected IE

Clinical criteria Alternate diagnosis

2 Major criteria or 1 major and 1 minor criteria Resolution of the infection with

1 major and 3 minor criteria Or antibiotic treatment for <4 days

Or 5 minor criteria 3 minor criteria No histological evidence

Definition of terms

Major criteria

1. Positive blood cultures

2. Evidence of endocardial involvement (TTE/TEE; histological specimen)

3. New valvular regurgitation (clinical modification of pre-existing murmur not enough)

Minor criteria

1. Predisposition (previous IE, predisposing heart condition, injection drug use)

2. Fever, temperature >38 ° C

3. Vascular phenomena

4. Immunologic phenomena

5. Microbiological evidence: positive BC that not met major criteria characteristics

Echocardiographic minor criteria eliminated

‘‘St Thomas” minor criteria, proposed by Lamas & Eykyn, not added but helpful in judgement: CRP > 100 mg/l, ESR elevation,

splenomegaly, haematuria, clubbing, splinter haemorrhagia, petechiae and purpura, central non-feeding venous lines, peripheral venous

lines (18)

TABLE 4. Diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis (IE)

Adapted from references (2,3,17,18)

Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011 293

ENDOCARDITIS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

TREATMENT that emerged in the past years and has today a

quite well applicability with >250,000 pa-

T he treatment of endocarditis represents a

major triumph of “modern medicine” and a

continuing challenge. Antibiotic and surgical

tients/year reported in the USA and it is used to

consolidate antimicrobial therapy (21). The fol-

lowing reasons may be responsible for OPAT

therapies together with complication manage- expansion: established safety, hospitals cost sa-

ment are now the keystone of disease manage- vings, new antibiotics that permit a longer spa-

ment. cing of doses, new diagnostic and reliable mo-

1) Antimicrobial therapy nitoring technology, interested and trained

Effective antimicrobial therapies consist first medical professionals, patient preference and

in identification of the specific pathogen and benefits, prompt return to work. Risks of OPAT

assessment of its susceptibility to antimicrobial are treatment failure or complications (line pro-

agents. blems, thrombosis, and anaphylaxis). Patient-

Minimal requirements for an effective anti- Selection Criteria are the following: medically

microbial regimen include the following: bac- stable patient (established control of infection-

tericidal activity; high concentrations of the related complications), after 2 weeks of hospi-

antimicrobial agent in the vegetation; prolon- tal therapy. Exceptionally OPAT is accepted for

ged duration of antimicrobial therapy; dosing the first phase of treatment if the patient re-

should be frequent enough to prevent the mains stable, without complication and with IE

growth of microorganisms between doses. due to oral streptococci etiology, otherwise

In severely ill patients at risk of death, empi- OPAT it is not recommended in the first phase.

rical antibiotic therapy should be started prom- After discharge the patient should be moni-

ptly after a classic minimum of three sets of blo- tored daily by a nurse and once or twice per

od cultures at 30 min interval are drawn (19). week by responsible doctor (22).

Associations between different classes are 2) Surgical therapy

developed and studied over the time in order Surgery can be required in up to 50% of IE

to cover a wide spectrum of isolates. Antimi- cases in which the cure with antibiotic treat-

crobial activity should be evaluated properly ment appear improbable (7). The main indica-

and toxic effects of drugs should be evaluated tions for surgery are the following:

sequentially (20). 1) heart failure with hemodynamic instabili-

Treatment must be adjusted immediately af- ty which remain refractory to the medical treat-

ter identification of the pathogen. Proposed ment

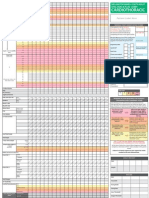

ESC empirical treatment for patients with IE is 2) uncontrolled infection with complication

exposed in Table 5. 3) prevention of systemic embolism in pa-

Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy tient with large or very large vegetation with an

(OPAT) for infective endocarditis is a concept embolic event or other predictors of a compli-

Dose, route, duration

Ampicillin Sulbactam 12 g/ day iv in 4 doses 4-6W

(Amoxicillin Clavulanate)

plus

Gentamicine 3 mg/kg/day in 2- 3 doses iv/im 4 -6 W

Or

NVE &

Vancomycin 30 mg/ kg/day in 2 doses IV 4-6W

Late PVE

Plus

Gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day in 2-3 doses iv/im 4-6W

Plus

Ciprofloxacin 1000 mg/day in 2 doses orally 4-6W

Or 800 mg/day in 2 doses iv

Vancomycin 30 mg/ kg/day in 2 doses IV6W

Plus

Early PVE Gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day in 2-3 doses iv/im 2W

Plus

Rifampin 1200 mg/day in 2 doses orally

TABLE 5. ESC suggested recommendation for empirical antibiotic therapy in endocarditis

NVE - native valve endocarditis; PVE - prosthetic valve endocarditis, W- weeks

Adapted from reference (3)

294 Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011

ENDOCARDITIS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

cated course despite appropriate antimicrobial gtime use of antibiotics for endocarditis pro-

treatment phylaxis in patients with predisposing cardiac

The timing of surgery, early or late in evolu- conditions prior specific procedures. Decisions

tion, is still controversial, with advantages and were based primarily on observational studies

disadvantages for both (Table 6) (23,24). Early and expert opinion.

valve surgery appears beneficial in terms of Today many concerns appear related to an-

long-term survival and improved prognosis, but tibiotic resistance against microorganisms in-

is correlated with increased early postoperative volved in IE triggered by antibiotic overuse.

mortality (25). There is no convincing evidence that antibiotic

IE mortality in surgical intervention for re- prophylaxis for every predisposing cardiac le-

moval of infected tissues and reconstruction of sion was cost-effective (26).

cardiac morphology vary from 5 to15% and is In the past years, working groups of the

related to microbial etiology, the extent of American Heart Association (27,28) and the

damage of cardiac structures, the left ventricu- European Society of Cardiology (3) have revi-

lar dysfunction, and the patient’s hemodynam- sed their guidelines and has limited also EI pro-

ic status at the time of surgery (3). phylaxis to the highest risk patients (Table 7)

It is of greatest importance that cardiolo- undergoing the highest risk procedures (Table

gists, microbiologists and cardiac surgeons co- 8). ESC recommended prophylaxis consist of

operate closely if IE occurs; especially if pros- amoxicillin or ampicillin, single dose 30-60 mi-

thetic valve endocarditis is suspected or nutes before procedures, 2 g po or iv, or in case

definite. Other complications management of of allergy clindamycin 600 mg po or iv, same

infective endocarditis is not the purpose of this timing.

paper. Current opinion is that the prevention sho-

New Principle of IE Prophylaxis uld begin first with general measures such: sur-

The hypotheses of bacteriemia prevention gical correction of congenital heart defects,

and/or minimization have determined the lon- maintaining good oral hygiene, dental prob-

Emergency Surgery (within 24 h)

- IE with refractory pulmonary edema or cardiogenic shock determined by

Acute severe valvular regurgitation (aortic or mitral) or severe prosthetic dysfunction (dehiscence

or obstruction)

Fistula into a cardiac chamber or the pericardial space

Urgent Surgery (within days)

- IE with persistent heart failure, signs of hemodynamic instability on echocardiography

determined by acute severe valvular (aortic or mitral) regurgitation or obstruction

- Uncontrolled infection (large vegetation, abscess, pseudoaneurism, fistulae)

- Fever and positive blood cultures persistence >7–10 days

- Large mitral or aortic vegetation (>10 mm) with an embolic event despite suitable antimicrobial

treatment or other predictors of a complicated course(heart failure, persistent infection, abscess)

- Very large vegetation (>15 mm)

Early Elective Surgery (during the in-hospital stay)

- Severe aortic or mitral regurgitation with no heart failure

- Fungal or multiresistant infection infections resistant to medical therapy

TABLE 6. Timing of surgery in infective endocarditis

Adapted from reference (3,24)

1. Prosthetic cardiac valve

2. Previous IE

3. Selected congenital heart disease

Nonrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease, including palliative shunts and conduits

Repaired (surgically/by catheter intervention) congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or

device during the first 6 months after the procedure (until endothelialization occurs)

Repaired congenital heart disease with residual defects at the side or adjacent to the site of a

prosthetic patch or device

TABLE 7. The highest risk patients for infective endocarditis

* only AHA recommend EI prophylaxis for Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

Adapted from (3,28)

Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011 295

ENDOCARDITIS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Both guideline

Dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissues or periapical region of teeth, or

perforation of oral mucosa

AHA guideline only

Procedures on respiratory tract or infected skin, skin structures, or musculoskeletal tissues only

if they imply overt incision of the skin or mucosa (ESC guideline recommend prophylaxis when a

proven infection of those structures require specific intervention)

TABLE 8. The highest risk procedures for infective endocarditis

Adapted from (3,28)

lems ended before prosthetic valves implant, ABREVIATIONS

avoiding procedures that determine bacterie-

mia, minimizing the use of central intravascular AHA American Heart Association

catheters and urinary catheters and promptly BC blood cultures

treating any infection. CRP C reactive protein

ESC European Society of Cardiology

CONCLUSION ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

IE Infective endocarditis

I f untreated, IE remains a fatal disease. Unfor-

tunately lots of guidelines are often based on

expert opinion because of the low incidence of

IIa ESC expert opinion recommendation of ESC

III ESC contraindication

Im intramuscular

the disease, the absence of randomized trials, IV intravenous

and the limited number of meta-analyses (29). NVE native valve endocarditis

Successful management depends on the close OPAT Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy

cooperation of medical and surgical disciplines. PCR polymerase chain reaction

This collaboration has markedly improved the PVE prosthetic valve endocarditis

outcome of the disease. TEE Transoesophageal echocardiography

TTE Transthoracic echocardiography

REFERENCES

1. Lerner PI, Weinstein L – Infective 5. de Sa DDC, Tleyjeh IM, Anavekar NS, Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:131-140.

endocarditis in the antibiotic era. N et al. – Epidemiological trends of 9. Karchmer AW – Infective Endocarditis.

Engl J Med 1966;274:199. infective endocarditis: a population In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes D P,

2. Fowler VG, Scheld WM, Bayer AS based study in Olmsted County, Libby P, eds. Braunwald’s Heart

– Endocarditis and intravascular Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular

infections. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, 85:422-426. Medicine, 9th Ed. Elsevier Saunders,

Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practices of 6. Aksoy O, Meyer LT, Cabell CH, et al. 2012;1540-1558

Infectious Diseases 6th ed. Elsevier – Gender differences in infective 10. Osler W – Gulstonian lectures on

Churchill Livingstone; 2005;975-1021. endocarditis: pre- and co-morbid malignant endocarditis. Lancet 1885; 1:

3. Bruno Hoen, Pilar Tornos, Habib G, et conditions lead to different manage- 415-508.

al. – Guidelines on the prevention, ment and outcomes in female patients. 11. Millar BC, Moore JE – Current trends

diagnosis, and treatment of infective Scand J Infect Dis 2007;39:101-107. in the molecular diagnosis of infective

endocarditis (new version 2009): the 7. Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, et al. endocarditis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect

Task Force on the Prevention, Diagno- – Clinical presentation, etiology, and Dis 2004;23:353-365.

sis, and Treatment of Infective outcome of infective endocarditis in the 12. Fenollar F, Raoult D – Molecular

Endocarditis of the ESC. Eur Heart J 21st century. Arch Intern Med 2009; diagnosis of bloodstream infections

2009;30:2369-2413. 169:463. caused by non-cultivable bacteria. Int J

4. Hoen B, Alla F, Selton-Suty C, et al. 8. Fournier PE, Thuny F, Richet H, et al. Antimicrob Agents 2007;30 Suppl

– Changing profile of infective – Comprehensive diagnostic strategy 1:S7-S15.

endocarditis: results of a 1-year survey for blood culture-negative endocarditis: 13. Hill EE, Herijgers P, Claus P, et al.

in France. JAMA 2002;288:75-81. a prospective study of 819 new cases. – Abscess in infective endocarditis: the

296 Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011

ENDOCARDITIS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

value of transesophageal echocardiog- 19. Lee A, Mirrett S, Reller LB, et al. 24. Prendergast BD, Tornos P – Surgery

raphy and outcome: a 5-year study. Am – Detection of bloodstream infections in for infective endocarditis: who and

Heart J 2007;154:923-928. adults: how many blood cultures are when? Circulation 2010;121:1141-1152.

14. Feuchtner GM, Stolzmann P, Dichtl needed? J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:3546- 25. Bannay A, Hoen B, Duval X, et al.

W, et al. – Multislice computed 3548. – The impact of valve surgery on short

tomography in infective endocarditis: 20. Buchholtz K, Larsen CT, Hassager C, and long-term mortality in left-sided

comparison with transesophageal et al. – Severity of gentamicin’s infective endocarditis: do differences in

echocardiography and intraoperative nephrotoxic effect on patients with methodological approaches explain

findings. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; infective endocarditis: a prospective previous conflicting results? Eur Heart J

53:436-444. observational cohort study of 373 2011;32:2003-2015.

15. Evangelista A, Gonzalez-Alujas MT patients. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:65-71. 26. Bogle RG, Bajpai A – Antibiotic

– Echocardiography in infective 21. Tice AD, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, et al. Prophylaxis Against Infective Endocar-

endocarditis. Heart 2004; 90:614-617. – Practice guidelines for outpatient ditis: New Guidelines, New Contro-

16. Habib G, Badano L, Tribouilloy C, et parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA versy? Br J Cardiol 2008;15:279-280

al. – Recommendations for the practice guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 27. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et

of echocardiography in infective 38:1651-1672. al. – Prevention of infective endocardi-

endocarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr 2010; 22. Andrews MM, von Reyn CF – Patient tis. Circulation 2007;116:1736-1754.

11:202-219. selection criteria and management 28. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee

17. Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK guidelines for outpatient parenteral K, et al. – 2008 focused update

– New criteria for diagnosis of infective antibiotic therapy for native valve infec- incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006

endocarditis: utilization of specific tive endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2001; guidelines for the management of

echocardiographic findings. Duke 33:203-209. patients with valvular heart disease: a

Endocarditis Service. Am J Med 1994; 23. Lalani T, Cabell CH, Benjamin DK, et report of the ACC/AHA Task Force on

96:200-209. al. – Analysis of the impact of early Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol

18. Lamas CC, Eykyn SJ – Suggested surgery on in hospital mortality of 2008;52:e1-142.

modifications to the Duke criteria for native valve endocarditis: use of 29. Naber CK, Erbel R, Baddour LM, et al.

the clinical diagnosis of native valve propensity score and instrumental – New guidelines for infective

and prosthetic valve endocarditis: an- variable methods to adjust for endocarditis: a call for collaborative

alysis of 118 pathologically proven ca- treatment-selection bias. Circulation research. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007;

ses. Clin Infect Dis 1997 Sep; 25:713-9. 2010; 121:1005-1013. 29:615-616.

Maedica A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011 297

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Stealth Adapted Viruses; Alternative Cellular Energy (Ace) & Kelea Activated Water: A New Paradigm of HealthcareD'EverandStealth Adapted Viruses; Alternative Cellular Energy (Ace) & Kelea Activated Water: A New Paradigm of HealthcarePas encore d'évaluation

- Secondary HypertensionD'EverandSecondary HypertensionAlberto MorgantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis: Indian Scenario: Rajeev GuptaDocument7 pagesInfective Endocarditis: Indian Scenario: Rajeev GuptapreetPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective EndocarditisDocument18 pagesInfective EndocarditisLee Foo WengPas encore d'évaluation

- Infectious EndocarditisDocument49 pagesInfectious EndocarditisDennisFrankKondoPas encore d'évaluation

- 325 FullDocument20 pages325 FullDessyadoePas encore d'évaluation

- Infective EndocarditisDocument16 pagesInfective EndocarditisAnnisa UlfaPas encore d'évaluation

- Endocarditis Nature 1Document13 pagesEndocarditis Nature 1NAREN FAVIAN BRAVO BRAVOPas encore d'évaluation

- CO - Endocarditis in Critically Ill PatientsDocument8 pagesCO - Endocarditis in Critically Ill PatientsRomán Wagner Thomas Esteli ChávezPas encore d'évaluation

- ENDOCARDITISDocument4 pagesENDOCARDITISrnsharmasPas encore d'évaluation

- DR Bragg - Endocarditis - Pediatric in Review April 2014Document9 pagesDR Bragg - Endocarditis - Pediatric in Review April 2014angelicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Moreillon2004 PDFDocument11 pagesMoreillon2004 PDFMery Luz RojasPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective EndocarditisDocument67 pagesInfective EndocarditisDr. Rajesh PadhiPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Cir 98 25 2936Document13 pages01 Cir 98 25 2936Ikhsan Amadea9969Pas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis: Dwi Ariyanti, MD (Fiha) Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Jember 2016Document34 pagesInfective Endocarditis: Dwi Ariyanti, MD (Fiha) Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Jember 2016Aji rahmat HidayahPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 1016@j Mayocp 2019 12 008 PDFDocument16 pages10 1016@j Mayocp 2019 12 008 PDFfadmayulianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Ischaemic Stroke in Infective Endocarditis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Treated With Reperfusion TherapyDocument13 pagesAcute Ischaemic Stroke in Infective Endocarditis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Treated With Reperfusion TherapyPatrick NunsioPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis: Ainal Fadly Adigama PF Enny SuryantiDocument50 pagesInfective Endocarditis: Ainal Fadly Adigama PF Enny SuryantiFaisal Reza AdiebPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis-Update For The Perioperative ClinicianDocument13 pagesInfective Endocarditis-Update For The Perioperative ClinicianMiguel PugaPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis PDFDocument6 pagesInfective Endocarditis PDFMaya WijayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis (Ie) : Mengist Awoke (MSC, Assistant Professor)Document29 pagesInfective Endocarditis (Ie) : Mengist Awoke (MSC, Assistant Professor)Digafe TolaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020 Article 435Document25 pages2020 Article 435Carlos Peña PaterninaPas encore d'évaluation

- Endocarditis Pediatric in ReviewDocument9 pagesEndocarditis Pediatric in ReviewAngela LópezPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionDocument10 pagesInfective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionSarah Ariefah SantriPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Update: Authors: Ronak RajaniDocument5 pagesInfective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Update: Authors: Ronak RajanicositaamorPas encore d'évaluation

- Bacterial EndocarditisDocument14 pagesBacterial EndocarditisSubhanAnwarKhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Native-Valve Infective Endocarditis: Clinical PracticeDocument10 pagesNative-Valve Infective Endocarditis: Clinical PracticeRaul DoctoPas encore d'évaluation

- Aneurism A Aorta InfectadoDocument6 pagesAneurism A Aorta InfectadoYgor AlbuquerquePas encore d'évaluation

- E000174 Full PDFDocument9 pagesE000174 Full PDFRicardo Costa da SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1882-Article Text-7722-1-10-20200608 PDFDocument6 pages1882-Article Text-7722-1-10-20200608 PDFRyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis Today (Version 1 Peer Review: 1 Not Approved)Document9 pagesInfective Endocarditis Today (Version 1 Peer Review: 1 Not Approved)preetPas encore d'évaluation

- Sepsis Therapies: Learning From 30 Years of Failure of Translational Research To Propose New LeadsDocument24 pagesSepsis Therapies: Learning From 30 Years of Failure of Translational Research To Propose New LeadsMark TomPas encore d'évaluation

- Pathogens: Nosocomial Infections: Do Not Forget The Parasites!Document22 pagesPathogens: Nosocomial Infections: Do Not Forget The Parasites!lee suk moPas encore d'évaluation

- Seminar - Infective EndocarditisDocument12 pagesSeminar - Infective EndocarditisJorge Chavez100% (1)

- Endocard BartonDocument4 pagesEndocard BartonKrull TTTeamPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective EndocarditisDocument68 pagesInfective EndocarditisDr. Rajesh PadhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Adults 5Document5 pagesAdults 5Bshara SleemPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnostic and Terapi in Infection in Solid TransplantDocument19 pagesDiagnostic and Terapi in Infection in Solid TransplantretnoPas encore d'évaluation

- CASE STUDY - Infective EndocarditisDocument6 pagesCASE STUDY - Infective EndocarditisDudil GoatPas encore d'évaluation

- Pathology and Pathogenesis of Infective Endocarditis in Native Heart ValvesDocument8 pagesPathology and Pathogenesis of Infective Endocarditis in Native Heart ValvesIrina TănasePas encore d'évaluation

- Use Only: Sepsis: Implication For NursingDocument4 pagesUse Only: Sepsis: Implication For NursingDeo RizkyandriPas encore d'évaluation

- Disease of Endocardium, Myocardium and PericardiumDocument54 pagesDisease of Endocardium, Myocardium and PericardiumadystiPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis Case ReportDocument40 pagesInfective Endocarditis Case Reportliu_owen17100% (1)

- Wu Et Al 2017 - Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Infective Endocarditis in Children in ChinaDocument10 pagesWu Et Al 2017 - Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Infective Endocarditis in Children in ChinaOktadoni SaputraPas encore d'évaluation

- Endocarditis in The Intensive Care Unit An UpdateDocument10 pagesEndocarditis in The Intensive Care Unit An Updatecarper454Pas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis AbnetDocument198 pagesInfective Endocarditis AbnetAbnet WondimuPas encore d'évaluation

- Report EndocarditisDocument38 pagesReport EndocarditisCamille MarasiganPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardiac EmergenciesDocument21 pagesCardiac Emergenciesgus_lionsPas encore d'évaluation

- EndocarditisDocument53 pagesEndocarditisمحمد ربيعيPas encore d'évaluation

- Sbe in ChildrenDocument42 pagesSbe in Childrengrim reaperPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture Infective EndocarditisDocument37 pagesLecture Infective EndocarditisJohnson OlawalePas encore d'évaluation

- AaaaDocument57 pagesAaaaandreva8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Myocarditis: Leslie T. Cooper Jr. and Kirk U. KnowltonDocument21 pagesMyocarditis: Leslie T. Cooper Jr. and Kirk U. KnowltonAnonymous cdLyeXKBPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy and Management of Infective Endocarditis, and Its ComplicationsDocument7 pages2022 Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy and Management of Infective Endocarditis, and Its ComplicationsstedorasPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Anesthetic and Obstetric ConsiderationsDocument9 pagesHuman Immunodeficiency Virus: Anesthetic and Obstetric ConsiderationsNani OktaviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Kidney Injury1Document16 pagesAcute Kidney Injury1Hmn07Pas encore d'évaluation

- Frenemies Within: An Endocarditis Case in Behçet's DiseaseDocument12 pagesFrenemies Within: An Endocarditis Case in Behçet's DiseaseCatherine MorrisPas encore d'évaluation

- JTD 11 01 21Document8 pagesJTD 11 01 21Kornelis AribowoPas encore d'évaluation

- Infective Endocarditis: Update On Epidemiology, Outcomes, and ManagementDocument9 pagesInfective Endocarditis: Update On Epidemiology, Outcomes, and ManagementRaul Cesar Solis EndaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Auto-Inflammatory Syndromes: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and ManagementD'EverandAuto-Inflammatory Syndromes: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and ManagementPetros EfthimiouPas encore d'évaluation

- The Analysis and Reflection On That Sugar FilmDocument2 pagesThe Analysis and Reflection On That Sugar FilmkkkkPas encore d'évaluation

- Breast Imaging Review - A Quick Guide To Essential Diagnoses (2nd Edition) PDFDocument264 pagesBreast Imaging Review - A Quick Guide To Essential Diagnoses (2nd Edition) PDFGregorio Parra100% (2)

- Adult Early Warning Score Observation Chart For Cardiothoracic UnitDocument1 pageAdult Early Warning Score Observation Chart For Cardiothoracic UnitalexipsPas encore d'évaluation

- NCPDocument14 pagesNCPclaidelynPas encore d'évaluation

- SCIT 1408 Applied Human Anatomy and Physiology II - Urinary System Chapter 25 BDocument50 pagesSCIT 1408 Applied Human Anatomy and Physiology II - Urinary System Chapter 25 BChuongPas encore d'évaluation

- ERCPDocument4 pagesERCPbilly wilsonPas encore d'évaluation

- DSM OcdDocument2 pagesDSM Ocdnmyza89Pas encore d'évaluation

- Complications of DiabetesDocument3 pagesComplications of Diabetesa7wfPas encore d'évaluation

- Ironfang Invasion - Players GuideDocument12 pagesIronfang Invasion - Players GuideThomas McDonaldPas encore d'évaluation

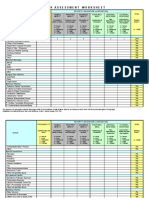

- IC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Document4 pagesIC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Juon Vairzya AnggraeniPas encore d'évaluation

- Histopathology of Dental CariesDocument7 pagesHistopathology of Dental CariesJOHN HAROLD CABRADILLAPas encore d'évaluation

- Kelseys ResumeDocument1 pageKelseys Resumeapi-401573835Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Nadi Vigyan by DR - Sharda Mishra MD (Proff. in Jabalpur Ayurved College)Document5 pagesThe Nadi Vigyan by DR - Sharda Mishra MD (Proff. in Jabalpur Ayurved College)Vivek PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- ACR-Global Hand Washing Day 2021Document2 pagesACR-Global Hand Washing Day 2021Katy Chenee Napao Perez100% (1)

- Tumor Marker Tests - CancerDocument4 pagesTumor Marker Tests - CancerMonna Medani LysabellaPas encore d'évaluation

- ResearchDocument28 pagesResearchReylon PachesPas encore d'évaluation

- 13) Technical Guideline On Irritation, Sensitization and Hemolysis Study For Chemical DrugsDocument36 pages13) Technical Guideline On Irritation, Sensitization and Hemolysis Study For Chemical DrugsAzam DanishPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal SociologyDocument53 pagesCriminal SociologyJackielyn cabayaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Care of The Client With High-Risk Labor & DeliveryDocument10 pagesNursing Care of The Client With High-Risk Labor & DeliveryWilbert CabanbanPas encore d'évaluation

- 3yc CrVlEemddAqBQMk Og 1.4 Six Artifacts From The Future of Food IFTF Coursera 2019Document13 pages3yc CrVlEemddAqBQMk Og 1.4 Six Artifacts From The Future of Food IFTF Coursera 2019Omar YussryPas encore d'évaluation

- Beauty Care 1st Summative TestDocument4 pagesBeauty Care 1st Summative TestLlemor Soled SeyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Tes TLMDocument16 pagesTes TLMAmelia RosyidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tamiflu and ADHDDocument10 pagesTamiflu and ADHDlaboewe100% (2)

- BELIZARIO VY Et Al Medical Parasitology in The Philippines 3e 158 226Document69 pagesBELIZARIO VY Et Al Medical Parasitology in The Philippines 3e 158 226Sharon Agor100% (1)

- Five Elements Chart TableDocument7 pagesFive Elements Chart TablePawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Zoology MCQs Practice Test 19Document4 pagesZoology MCQs Practice Test 19Rehan HaiderPas encore d'évaluation

- Physiology of The Cell: H. Khorrami PH.DDocument89 pagesPhysiology of The Cell: H. Khorrami PH.Dkhorrami4Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionDocument28 pagesSample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionLippincott Williams and Wilkins- Europe100% (1)

- Nclex Mnemonics 2020 2Document9 pagesNclex Mnemonics 2020 2Winnie OkothPas encore d'évaluation

- Eaves Nickolas A 201211 MASc ThesisDocument69 pagesEaves Nickolas A 201211 MASc Thesisrajeev50588Pas encore d'évaluation