Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Can Incentives Improve Medicaid Patient Engagement and Prevent Chronic Diseases?

Transféré par

Hyb Abu NajiyahTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Can Incentives Improve Medicaid Patient Engagement and Prevent Chronic Diseases?

Transféré par

Hyb Abu NajiyahDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

INVITED COMMENTARY

Can Incentives Improve Medicaid Patient

Engagement and Prevent Chronic Diseases?

Thomas J. Hoerger, Rebecca Perry, Kathleen Farrell, Stephanie Teixeira-Poit

Under the Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic also stressed that properly designed policies and incentives

Diseases model, 10 states are testing whether incentives can nudge individuals to make better decisions [4]. This

can encourage Medicaid beneficiaries to lose weight, stop emphasis has led to a renewed interest in using incentives to

smoking, work to prevent diabetes, or control risk factors for promote health behaviors.

other chronic diseases. This commentary describes these Kane and colleagues reviewed 47 randomized controlled

incentive programs and how they will be evaluated. trials of economic incentives to encourage prevention, and

they concluded that the incentives worked 73% of the time

I

[5]. The authors found that economic incentives were effec-

n 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services tive for simple preventive care (one-time vaccination or pre-

(CMS) awarded grants to 10 states to develop Medicaid natal care), but they were uncertain about the size of the

Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) incentive that would be needed to sustain long-term effects.

programs. The programs test whether providing monetary More recent studies have found that economic incentives

incentives to Medicaid beneficiaries can enhance benefi- led to short-term weight loss [6-8]. These studies tied the

ciary engagement and help prevent chronic diseases. In this incentives to achievement of outcomes (weight loss) rather

commentary, we describe the MIPCD programs and discuss than to process variables (such as attendance in weight loss

the key questions they raise. We then describe how these classes).

questions are being addressed in the ongoing evaluation of Incentives have been rarely used in Medicaid programs.

these programs. In a review of such programs, Blumenthal and coauthors

found only 3 major incentive programs offered by state

Background Medicaid agencies [9]. Participation in the programs was

Chronic diseases—including cancer, diabetes, heart dis- relatively low, and most of the incentives were paid for child-

ease, respiratory conditions, and stroke—account for nearly hood prevention or office visits. The review reported that

60% of deaths and the majority of health care spending in evaluation of program effectiveness was limited; there was

the United States [1]. Many cases of chronic disease can be no clear evidence of a relationship between incentives and

prevented or delayed by quitting smoking, losing weight, effectiveness; and there were low levels of program aware-

exercising more, and/or better managing risk factors such ness among Medicaid beneficiaries. Blumenthal and coau-

as hypertension or high cholesterol. However, getting indi- thors recommended future study and better evaluation of

viduals to change their behavior is challenging. Old habits Medicaid incentive programs; they also cautioned against

are hard to break because the health benefits of prevention making incentive structures too complicated for partici-

accrue slowly in the future, while the immediate pleasures of pants, relying too heavily on providers to publicize the pro-

a tasty dessert or a welcome cigarette break must be given grams, and creating too many administrative complexities

up today and on a sustained basis. For people who qualify [9].

for Medicaid due to low income, the general challenges of

chronic disease prevention may be compounded by other

MIPCD Programs

challenges such as limited education, unemployment, poor In Section 4108 of the Patient Protection and Affordable

housing, other health problems, or unstable family relation- Care Act of 2010 (ACA), Congress authorized creation of

ships. In the face of these challenges, preventing chronic state MIPCD programs. Under this authority, CMS awarded

disease in the distant future may be a relatively low priority.

Economists have long espoused the importance of Electronically published July 1, 2015.

monetary incentives—both prices and cash subsidies—as Address correspondence to Dr. Thomas J. Hoerger, RTI International,

instruments to change individual behavior. More recently, 3040 Cornwallis Rd, PO Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709

(tjh@rti.org).

although psychologists and behavioral economists have

N C Med J. 2015;76(3):180-184. ©2015 by the North Carolina Institute

noted that people often make decisions that deviate in pre- of Medicine and The Duke Endowment. All rights reserved.

dictable ways from being perfectly rational [2, 3], they have 0029-2559/2015/76311

180 NCMJ vol. 76, no. 3

ncmedicaljournal.com

10 states grants with which to establish MIPCD pro-

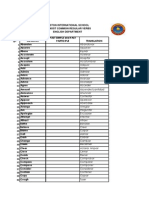

table 1.

grams; these states were California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Medical Conditions and Health Behaviors Targeted by State

Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New MIPCD Programs

York, Texas, and Wisconsin. States were given flexibility in

State Smoking Diabetes Obesity Hyperlipidemia Hypertension

designing their programs. The programs target a variety of

California 3 — — — —

conditions and behaviors, including tobacco use, diabetes,

Connecticut 3 — — — —

obesity, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension (see Table 1).

Hawaii — 3 — — —

Tobacco cessation programs in California, Connecticut, and

Minnesota — 3 3 — —

Wisconsin combine existing tobacco quit lines with incen-

Montana — 3 3 3 3

tives and additional services. Minnesota, Montana, and

Nevada — 3 3 3 3

some of the program arms in Nevada and New York pro-

New Hampshire 3 — 3 — —

vide diabetes prevention programs. In Nevada, the largest

New York 3 3 — — 3

program arm serves children who are at risk for heart dis- Texas 3 3 3 3 3

ease, whereas the state’s other programs serve adults. New Wisconsin 3 — — — —

Hampshire and Texas have developed programs that focus Total 6 6 5 3 4

on persons with mental health conditions or substance use Note. MIPCD, Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases.

issues.

Incentives vary across states (see Table 2), with most incentive programs, is it possible for states to implement

programs providing cash payments, debit cards, or mone- successful programs? If implemented, will beneficiaries par-

tary-value incentives. Incentive amounts range from $20 in ticipate? If beneficiaries participate, will they be satisfied

California’s simplest program arm to $1,150 per year in Texas with their access to programs and the quality of these pro-

(see Table 3). Texas has a unique program that offers a well- grams? Can specific segments of the Medicaid population

ness account and health navigators to persons with previ- participate, including children, people with mental illness,

ous mental health conditions or substance abuse issues. In and/or people with substance abuse issues? Will participa-

most states, incentives are integrated with supportive ser- tion in the MIPCD programs reduce medical care utilization

vices such as diabetes prevention classes, tobacco cessation and costs? How much will it cost to administer a statewide

classes, wellness coaches, nicotine replacement therapy, program? Finally—and most importantly—do participants in

and/or access to gyms. the incentives programs change their health behaviors and

The first MIPCD program began enrolling beneficiaries in achieve better health outcomes?

January of 2012, and all of the states had begun enrollment

Evaluation

by June of 2013. As of December 31, 2014, a total of 17,134

beneficiaries had enrolled in these programs. The programs Recognizing the importance of answering these ques-

are currently authorized to provide incentives through tions, Congress authorized the MIPCD programs as dem-

December 31, 2015. onstration projects and required both state and national

evaluations of the programs. Each state is required to evalu-

Key Questions ate the effectiveness of its program(s), with special empha-

The incentive programs raise a number of important sis on measuring and validating changes in health behaviors

questions. First, given limited experience with Medicaid and outcomes. To achieve this goal, most states have ran-

table 2.

Participant Incentives in State MIPCD Programs

Flexible spending Prevention- Treatment- Points Support to

Money-valued accounts for related related redeemable address barriers

State Money incentives wellness activities incentives incentives for rewards to participation

California — 3 — — 3 — —

Connecticut 3 — — — — — —

Hawaii 3 3 — 3 — 3 3

Minnesota 3 — — 3 — — 3

Montana 3 — — — — — 3

Nevada — — — — — 3 —

New Hampshire 3 — — 3 3 — 3

New York 3 — — — — — —

Texas — — 3 3 3 — 3

Wisconsin 3 3 — — — — 3

Total 7 3 1 4 3 2 6

Note. MIPCD, Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases.

NCMJ vol. 76, no. 3 181

ncmedicaljournal.com

Caveney sidebar

domly assigned beneficiaries between intervention arms addition, the national evaluation is examining the implemen-

(where beneficiaries receive incentives) and control arms tation process across states to synthesize findings from the

(where beneficiaries receive similar services but no incen- individual states. To examine these impacts, RTI is perform-

tives). States will provide evaluation reports after the pro- ing a mixed-methods evaluation using document review, site

grams stop providing incentives on December 31, 2015. visits, focus groups, a beneficiary survey, Medicaid claims

For the national evaluation, RTI International is per- analysis, and cost reports. Findings from the national evalu-

forming an independent assessment of several factors: ation will be included in 2 reports to Congress and a final

the programs’ impact on the utilization and costs of health evaluation report.

care services by participating Medicaid beneficiaries, the The initial report to Congress [10] was submitted in

extent to which specific populations can participate in the November of 2013 and provided early information on the

programs, the level of beneficiary satisfaction with access implementation and progress of the MIPCD programs.

to and quality of program services, and the administrative Implementation of the programs was delayed in some

costs required to implement and operate the programs. In states, but all states were able to implement the programs

182 NCMJ vol. 76, no. 3

ncmedicaljournal.com

Caveney sidebar continued

by June of 2013. Implementation challenges included admin- recommend for or against extending funding of the pro-

istrative delays and issues related to provider engagement, grams beyond January 1, 2016. Most of the State programs

identification of participants, and management of incen- have been enrolling participants for only a short period, and

tives. States sometimes changed their plans to overcome there are few data on the effect of the programs on health

these challenges. States learned that it was important to be outcomes or health care utilization and costs. Therefore, it

flexible in meeting challenges, to communicate closely with would be premature to make a recommendation to extend

partners and providers, to train and sometimes pay provid- funding to expand or extend the programs beyond January 1,

ers to participate, and to incorporate cultural awareness into 2016” [10].

the programs.

The initial report to Congress was required by law to

Discussion

include a recommendation on whether funding should be The MIPCD model is one of many initiatives in Title IV

expanded or extended beyond January 1, 2016. The report of the ACA that is designed to prevent chronic disease and

concluded, “At this time, there is insufficient evidence to improve public health. Although the ACA as a whole has

NCMJ vol. 76, no. 3 183

ncmedicaljournal.com

been widely debated, most observers recognize the impor- incentive programs can be implemented, but many other

tance of reducing the burden of chronic disease and asso- important evaluation questions have not yet been answered.

ciated costs—both to the US health care system in general The ongoing state and national evaluations will provide valu-

and to the Medicaid program in particular. Incentive pro- able evidence about whether Medicaid incentive programs

grams offer a potentially attractive means for better engag- can engage beneficiaries and whether they lead to better

ing Medicaid beneficiaries and encouraging them to change health behavior, improved health outcomes, and/or lower

unhealthy behaviors. As a result, 10 states were eager to test Medicaid costs.

Medicaid incentive programs.

Thomas J. Hoerger, PhD senior fellow, RTI International, Research

To date, the MIPCD programs have shown that Medicaid Triangle Park, North Carolina.

Rebecca Perry, MSc research public health analyst, RTI International,

table 3. Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.

MIPCD Incentives for Participants Kathleen Farrell, BA senior health researcher, RTI International,

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.

State Maximum financial incentive per persona Stephanie Teixeira-Poit, MS research public health analyst, RTI

International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.

California Eligible callers who ask for the Medi-Cal Incentives to

Quit (MIQS) incentive: Maximum study incentive: $20 Acknowledgments

Randomized controlled trial 1: Maximum study Financial support. RTI’s evaluation of Medicaid Incentives for the

incentive: $60 Prevention of Chronic Diseases programs is supported by Contract

Randomized controlled trial 2: Maximum study #HHSM500201000021i from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

incentive: $40 Services. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the

Enhanced services that are not part of a randomized authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the

controlled trial: TBD Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors are employees of RTI

Connecticut Maximum annual amount: $350

International.

Hawaii Maximum annual amount: $215

Minnesota Maximum study incentive: $545 References

Montana Maximum annual amount: $315 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Deaths: final

Nevadab Managed care organization for diabetes management: data for 2013: detailed tables for the National Vital Statistics Re-

Maximum study incentive: $355 port. CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/

nvsr64_02.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2015.

Managed care organization for weight management 2. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus

class: Maximum study incentive: $38 and Giroux; 2011.

Managed care organization for weight management 3. Ariely D. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our

support group: Maximum study incentive: $60 Decisions. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2008.

YMCA of Southern Nevada: Maximum study 4. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health,

incentive: $300 Wealth, and Happiness. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2008.

Healthy Hearts Program for Children: Maximum study 5. Kane RL, Johnson PE, Town RJ, Butler M. A structured review of the

incentive: $350 effect of economic incentives on consumers’ preventive behavior.

Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(4):327-352.

New Hampshire Weight loss: Maximum incentive for 24 months:

6. Finkelstein EA, Linnan LA, Tate DF, Birken BE. A pilot study testing the

$3,097

effect of different levels of financial incentives on weight loss among

Weight loss: Maximum incentives for 12 months: overweight employees. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(9):981-989.

$1,860 7. Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender J, Loewenstein

Smoking cessation: Maximum study incentive: $415 G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a random-

New York Maximum study incentive: $250 ized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2631-2637.

8. Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, et al. A randomized, controlled

Texas Maximum annual amount: $1,150

trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med.

Wisconsin Wisconsin Tobacco Quit Line: Maximum study 2009;360(7):699-709.

incentive: $270 9. Blumenthal KJ, Saulsgiver KA, Norton L, et al. Medicaid incentive

First Breath: Maximum study incentive: $600 programs to encourage healthy behavior show mixed results to

Note. MIPCD, Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; date and should be studied and improved. Health Aff (Millwood).

TBD, to be determined. 2013;32(3):497-507.

a

Projected maximum incentive amounts are based on information from state 10. Sebelius K. Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases

reports. Amounts may change during implementation. Evaluation: Initial Report to Congress. November 2013. http://inn

b

Nevada provides points that are redeemable for rewards; 100 points is equal ovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. Accessed April 1,

to $1. 2015.

184 NCMJ vol. 76, no. 3

ncmedicaljournal.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- How Proven Primary Prevention Can Stop DiabetesDocument4 pagesHow Proven Primary Prevention Can Stop DiabetesSteveEpsteinPas encore d'évaluation

- A ThingDocument60 pagesA ThingCholo MercadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Recovery: A Guide to Reforming the U.S. Health SectorD'EverandRecovery: A Guide to Reforming the U.S. Health SectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Perspective Mexico's Experience in Building a Toolkit for Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases Prevention - Rivera 2024 Perspective Mexicos experience_Document9 pagesPerspective Mexico's Experience in Building a Toolkit for Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases Prevention - Rivera 2024 Perspective Mexicos experience_SUSANA PEREZ CUTIÑOPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Reduce Healthcare Costs Through Better Medication Adherence For People Suffering From Chronic DiseaseDocument24 pagesHow To Reduce Healthcare Costs Through Better Medication Adherence For People Suffering From Chronic DiseaseDemocratic Governors AssociationPas encore d'évaluation

- Aca Poster Session-2Document1 pageAca Poster Session-2api-280156332Pas encore d'évaluation

- Current Systems of Health CareDocument4 pagesCurrent Systems of Health Carekangna_sharma20Pas encore d'évaluation

- Community Program Improves Quality of Life and Self-Management in Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus and ComorbidityDocument11 pagesCommunity Program Improves Quality of Life and Self-Management in Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus and ComorbidityZhafirah SalsabilaPas encore d'évaluation

- BC Guiding Framework For Public Health 2017 UpdateDocument58 pagesBC Guiding Framework For Public Health 2017 UpdateMayPas encore d'évaluation

- HipertensiDocument9 pagesHipertensinurmaliarizkyPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Cancer Detection in Primary Care: Are You Aware of New Blood-Based Multi-Cancer Screening ToolsD'EverandEarly Cancer Detection in Primary Care: Are You Aware of New Blood-Based Multi-Cancer Screening ToolsPas encore d'évaluation

- What's In, What's Out: Designing Benefits for Universal Health CoverageD'EverandWhat's In, What's Out: Designing Benefits for Universal Health CoveragePas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S2213076418300654 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2213076418300654 MaindaytdeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Medication Adherence in The Real WorldDocument13 pagesMedication Adherence in The Real WorldCognizantPas encore d'évaluation

- CCM-Diabetes Management for Chronic Disease PatientsDocument21 pagesCCM-Diabetes Management for Chronic Disease PatientsRobertPas encore d'évaluation

- Grant Proposal MmaskaiDocument13 pagesGrant Proposal Mmaskaiapi-617204367Pas encore d'évaluation

- TennCare, One State's Experiment with Medicaid ExpansionD'EverandTennCare, One State's Experiment with Medicaid ExpansionPas encore d'évaluation

- TennCare, One State's Experiment with Medicaid ExpansionD'EverandTennCare, One State's Experiment with Medicaid ExpansionPas encore d'évaluation

- Potential Savings Through Prevention of Avoidable Chronic Illness Among CalPERS State Active MembersDocument10 pagesPotential Savings Through Prevention of Avoidable Chronic Illness Among CalPERS State Active Membersjon_ortizPas encore d'évaluation

- Pills and the Public Purse: The Routes to National Drug InsuranceD'EverandPills and the Public Purse: The Routes to National Drug InsurancePas encore d'évaluation

- Medication A.R.E.A.S. Bundle: A Prescription for Value-Based Healthcare to Optimize Patient Health Outcomes, Reduce Total Costs, and Improve Quality and Organization PerformanceD'EverandMedication A.R.E.A.S. Bundle: A Prescription for Value-Based Healthcare to Optimize Patient Health Outcomes, Reduce Total Costs, and Improve Quality and Organization PerformancePas encore d'évaluation

- Rationale HLTH 640Document5 pagesRationale HLTH 640api-535492370Pas encore d'évaluation

- Global Budgeting Promoting Flexible Funding To Support Long Term Care ChoicesDocument25 pagesGlobal Budgeting Promoting Flexible Funding To Support Long Term Care ChoicesLeslie HendricksonPas encore d'évaluation

- Health System Approaches Are Needed To Expand Telemedicine Use Across Nine Latin American NationsDocument10 pagesHealth System Approaches Are Needed To Expand Telemedicine Use Across Nine Latin American NationsMEDICAL DEVICES Col. SASPas encore d'évaluation

- Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3): CancerD'EverandDisease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3): CancerPas encore d'évaluation

- Healthy Babies Are Worth The Wait: A Partnership to Reduce Preterm Births in Kentucky through Community-based Interventions 2007 - 2009D'EverandHealthy Babies Are Worth The Wait: A Partnership to Reduce Preterm Births in Kentucky through Community-based Interventions 2007 - 2009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetesd2019Document6 pagesStandards of Medical Care in Diabetesd2019EirPas encore d'évaluation

- Insuring National Health Care: The Canadian ExperienceD'EverandInsuring National Health Care: The Canadian ExperienceÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- Financial Incentives For Medicaid Beneficiaries With Diabetes: Lessons Learned From HI-PRAISE, An Observational Study and Randomized Controlled TrialDocument4 pagesFinancial Incentives For Medicaid Beneficiaries With Diabetes: Lessons Learned From HI-PRAISE, An Observational Study and Randomized Controlled TrialDavids MarinPas encore d'évaluation

- Disease, Diagnoses, and Dollars: Facing the Ever-Expanding Market for Medical CareD'EverandDisease, Diagnoses, and Dollars: Facing the Ever-Expanding Market for Medical CarePas encore d'évaluation

- Pone 0052963Document7 pagesPone 0052963SelyfebPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring The Science of Complementary and Alternative MedicineDocument68 pagesExploring The Science of Complementary and Alternative MedicineAurutchat VichaiditPas encore d'évaluation

- Controversy in U.S Healthcare System PolicyDocument5 pagesControversy in U.S Healthcare System Policydenis edembaPas encore d'évaluation

- HSC 405 Grant ProposalDocument28 pagesHSC 405 Grant Proposalapi-383936042100% (1)

- Healthcare Delivery SystemDocument2 pagesHealthcare Delivery SystemMark Teofilo Dela PeñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Healthy Competition: What's Holding Back Health Care and How to Free ItD'EverandHealthy Competition: What's Holding Back Health Care and How to Free ItPas encore d'évaluation

- Multidisciplinary Approach to the Management of ObesityD'EverandMultidisciplinary Approach to the Management of ObesityPas encore d'évaluation

- Code Red: An Economist Explains How to Revive the Healthcare System without Destroying ItD'EverandCode Red: An Economist Explains How to Revive the Healthcare System without Destroying ItPas encore d'évaluation

- Private Versus Public Provision of Social Insurance: Evidence From MedicaidDocument3 pagesPrivate Versus Public Provision of Social Insurance: Evidence From MedicaidCato InstitutePas encore d'évaluation

- Buenger Elizabeth Business PlanDocument6 pagesBuenger Elizabeth Business Planapi-514993360Pas encore d'évaluation

- John Edwards 2008 - Reforming Health Care To Make It Affordable, Accountable, and Universal (June 14, 2007)Document27 pagesJohn Edwards 2008 - Reforming Health Care To Make It Affordable, Accountable, and Universal (June 14, 2007)politix100% (1)

- EBDM LowrezDocument32 pagesEBDM LowrezCarolina RechPas encore d'évaluation

- RelationDocument12 pagesRelationazizahfaniPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Activities That The State Government Performs For HealthcareDocument5 pages5 Activities That The State Government Performs For HealthcareWonder LostPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality of Primary Care in Low-Income Countries: Facts and EconomicsDocument41 pagesQuality of Primary Care in Low-Income Countries: Facts and EconomicsNop PiromPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.1 Primary Health Care and NutritionDocument5 pages1.1 Primary Health Care and NutritionEmilyBaquePas encore d'évaluation

- Why Are We Failing To Address The Issue of Access To Insulin A National and Global PerspectiveDocument7 pagesWhy Are We Failing To Address The Issue of Access To Insulin A National and Global PerspectiveJohn LópezPas encore d'évaluation

- TheQuarryLaneSchool KhMe Neg Quarry Lane Invitational Round 3Document43 pagesTheQuarryLaneSchool KhMe Neg Quarry Lane Invitational Round 3EmronPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIID'EverandAnti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIIPas encore d'évaluation

- A Holistic Approach For The US Behavioral Health Crisis During The COVID 19 Pandemic PDFDocument9 pagesA Holistic Approach For The US Behavioral Health Crisis During The COVID 19 Pandemic PDFSUBHAM KUMARPas encore d'évaluation

- Artikel Pubmed 3Document6 pagesArtikel Pubmed 3Sofa AmaliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Obesity: Halting The Epidemic by Making Health EasierDocument4 pagesObesity: Halting The Epidemic by Making Health EasierTABIBI11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Epidemiology of adult obesity in CanadaDocument8 pagesEpidemiology of adult obesity in CanadaJanmarie Barrios MedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes en LatinoaméricaDocument6 pagesDiabetes en LatinoaméricaJean CorralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Screening Strategies For Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review ProtocolDocument11 pagesScreening Strategies For Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review ProtocolAminatus ZahroPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardenas 2016 Diabetes PeruDocument9 pagesCardenas 2016 Diabetes PeruJean M Huaman FiallegaPas encore d'évaluation

- GHFGHHDocument1 pageGHFGHHHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Kepuasan Perawat 1Document8 pagesKepuasan Perawat 1Hyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.1 Analisis Faktor Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi PDFDocument19 pages2.1 Analisis Faktor Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi PDFHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Faktor-Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Kinerja Kader PDFDocument13 pagesFaktor-Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Kinerja Kader PDFHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.1 Analisis Faktor Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi PDFDocument19 pages2.1 Analisis Faktor Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi PDFHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Faktor - Faktor Yang Berhubungan DenganDocument11 pagesAnalisis Faktor - Faktor Yang Berhubungan DenganHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.1 Analisis Faktor Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi PDFDocument19 pages2.1 Analisis Faktor Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi PDFHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Pengaruh Lingkungan Kerja, Disiplin Kerja Dan MotivasiDocument10 pagesPengaruh Lingkungan Kerja, Disiplin Kerja Dan MotivasiHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Faktor - Faktor Yang Berhubungan DenganDocument11 pagesAnalisis Faktor - Faktor Yang Berhubungan DenganHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- 1600 3329 1 SMDocument10 pages1600 3329 1 SMHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Focus 16 Web PDFDocument303 pagesFocus 16 Web PDFLaluAlfiandZartadiPas encore d'évaluation

- ..Karakteristik Sosial Demografi Dan Faktor PDFDocument10 pages..Karakteristik Sosial Demografi Dan Faktor PDFHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Judul TesisDocument8 pagesJudul TesisHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Insurance For The Indigent People in Indonesia: by PT. Askes, IndonesiaDocument7 pagesHealth Insurance For The Indigent People in Indonesia: by PT. Askes, IndonesiaHyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Shi 1Document18 pagesShi 1Hyb Abu NajiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Sistem Pembiayaan KesehatanDocument13 pagesSistem Pembiayaan KesehatanDewi KusumawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On Effectiveness of Ware Housing System in Flyton XpressDocument23 pagesA Study On Effectiveness of Ware Housing System in Flyton XpressmaheshPas encore d'évaluation

- The Beatles - Allan Kozinn Cap 8Document24 pagesThe Beatles - Allan Kozinn Cap 8Keka LopesPas encore d'évaluation

- Ava Gardner Biography StructureDocument5 pagesAva Gardner Biography Structuredanishfiverr182Pas encore d'évaluation

- C++ Project On Library Management by KCDocument53 pagesC++ Project On Library Management by KCkeval71% (114)

- Noise Blinking LED: Circuit Microphone Noise Warning SystemDocument1 pageNoise Blinking LED: Circuit Microphone Noise Warning Systemian jheferPas encore d'évaluation

- Revised Answer Keys for Scientist/Engineer Recruitment ExamDocument5 pagesRevised Answer Keys for Scientist/Engineer Recruitment ExamDigantPas encore d'évaluation

- The Revival Strategies of Vespa Scooter in IndiaDocument4 pagesThe Revival Strategies of Vespa Scooter in IndiaJagatheeswari SelviPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 018Document12 pagesChapter 018api-281340024Pas encore d'évaluation

- People V Gona Phil 54 Phil 605Document1 pagePeople V Gona Phil 54 Phil 605Carly GracePas encore d'évaluation

- Music Literature (Western Music)Document80 pagesMusic Literature (Western Music)argus-eyed100% (6)

- IAS Exam Optional Books on Philosophy Subject SectionsDocument4 pagesIAS Exam Optional Books on Philosophy Subject SectionsDeepak SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- OF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THDocument3 pagesOF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THAryann Gupta100% (1)

- GST Project ReportDocument29 pagesGST Project ReportHENA KHANPas encore d'évaluation

- CL Commands IVDocument626 pagesCL Commands IVapi-3800226100% (2)

- Boeing 7E7 - UV6426-XLS-ENGDocument85 pagesBoeing 7E7 - UV6426-XLS-ENGjk kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Credit Card Statement: Payment Information Account SummaryDocument4 pagesCredit Card Statement: Payment Information Account SummaryShawn McKennanPas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument2 pagesPDFJahi100% (3)

- Glass Fiber CompositesDocument21 pagesGlass Fiber CompositesChoice NwikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Court Rules on Debt Collection Case and Abuse of Rights ClaimDocument3 pagesCourt Rules on Debt Collection Case and Abuse of Rights ClaimCesar CoPas encore d'évaluation

- W220 Engine Block, Oil Sump and Cylinder Liner DetailsDocument21 pagesW220 Engine Block, Oil Sump and Cylinder Liner DetailssezarPas encore d'évaluation

- Challan Form OEC App Fee 500 PDFDocument1 pageChallan Form OEC App Fee 500 PDFsaleem_hazim100% (1)

- 150 Most Common Regular VerbsDocument4 pages150 Most Common Regular VerbsyairherreraPas encore d'évaluation

- No-Vacation NationDocument24 pagesNo-Vacation NationCenter for Economic and Policy Research91% (54)

- Schumann Op15 No5 PsuDocument1 pageSchumann Op15 No5 PsuCedric TutosPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Mass Communication Solved MCQs (Set-3)Document5 pagesIntroduction To Mass Communication Solved MCQs (Set-3)Abdul karim MagsiPas encore d'évaluation

- Safety Data Sheet - en - (68220469) Aluminium Silicate QP (1318!74!7)Document6 pagesSafety Data Sheet - en - (68220469) Aluminium Silicate QP (1318!74!7)sergio.huete.hernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Ra 1425 Rizal LawDocument7 pagesRa 1425 Rizal LawJulie-Mar Valleramos LabacladoPas encore d'évaluation

- 20 Reasons Composers Fail 2019 Reprint PDFDocument30 pages20 Reasons Composers Fail 2019 Reprint PDFAlejandroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Conflict With Slavery and Others, Complete, Volume VII, The Works of Whittier: The Conflict With Slavery, Politicsand Reform, The Inner Life and Criticism by Whittier, John Greenleaf, 1807-1892Document180 pagesThe Conflict With Slavery and Others, Complete, Volume VII, The Works of Whittier: The Conflict With Slavery, Politicsand Reform, The Inner Life and Criticism by Whittier, John Greenleaf, 1807-1892Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Hempel's Curing Agent 95040 PDFDocument12 pagesHempel's Curing Agent 95040 PDFeternalkhut0% (1)