Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

History of Logic Ali Danish Assignement

Transféré par

Ghulam MustafaCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

History of Logic Ali Danish Assignement

Transféré par

Ghulam MustafaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

History of Logic:

The history of logic deals with the study of the development of the science of

valid inference (logic). Formal logics developed in ancient times in China, India, and Greece. Greek

methods, particularly Aristotelian logic (or term logic) as found in the Organon, found wide

application and acceptance in Western science and mathematics for millennia. The Stoics,

especially Chrysippus, began the development of predicate logic.

Christian and Islamic philosophers such as Boethius (died 524) and William of Ockham (died 1347)

further developed Aristotle's logic in the Middle Ages, reaching a high point in the mid-fourteenth

century. The period between the fourteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century saw

largely decline and neglect, and at least one historian of logic regards this time as barren. Empirical

methods ruled the day, as evidenced by Sir Francis Bacon's Novum Organon of 1620.

Logic revived in the mid-nineteenth century, at the beginning of a revolutionary period when the

subject developed into a rigorous and formal discipline which took as its exemplar the exact method

of proof used in mathematics, a hearkening back to the Greek tradition. The development of the

modern "symbolic" or "mathematical" logic during this period by the likes of Boole, Frege, Russell,

and Peano is the most significant in the two-thousand-year history of logic, and is arguably one of

the most important and remarkable events in human intellectual history.

Progress in mathematical logic in the first few decades of the twentieth century, particularly arising

from the work of Gödel and Tarski, had a significant impact on analytic philosophy and philosophical

logic, particularly from the 1950s onwards, in subjects such as modal logic, temporal logic, deontic

logic, and relevance logic.

Rise of modern logic:

The period between the fourteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century had been

largely one of decline and neglect, and is generally regarded as barren by historians of logic. The

revival of logic occurred in the mid-nineteenth century, at the beginning of a revolutionary

period where the subject developed into a rigorous and formalistic discipline whose exemplar

was the exact method of proof used in mathematics. The development of the modern "symbolic"

or "mathematical" logic during this period is the most significant in the 2000-year history of

logic, and is arguably one of the most important and remarkable events in human intellectual

history.

A number of features distinguish modern logic from the old Aristotelian or traditional logic, the

most important of which are as follows:Modern logic is fundamentally a calculus whose rules of

operation are determined only by the shape and not by the meaning of the symbols it employs, as

in mathematics. Many logicians were impressed by the "success" of mathematics, in that there

had been no prolonged dispute about any truly mathematical result. C.S. Peircenote that even

though a mistake in the evaluation of a definite integral by Laplace led to an error concerning the

moon's orbit that persisted for nearly 50 years, the mistake, once spotted, was corrected without

any serious dispute. Peirce contrasted this with the disputation and uncertainty surrounding

traditional logic, and especially reasoning in metaphysics. He argued that a truly "exact" logic

would depend upon mathematical, i.e., "diagrammatic" or "iconic" thought. "Those who follow

such methods will ... escape all error except such as will be speedily corrected after it is once

suspected". Modern logic is also "constructive" rather than "abstractive"; i.e., rather than

abstracting and formalising theorems derived from ordinary language (or from psychological

intuitions about validity), it constructs theorems by formal methods, then looks for an

interpretation in ordinary language. It is entirely symbolic, meaning that even the logical

constants (which the medieval logicians called "syncategoremata") and the categoric terms are

expressed in symbols.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- History of LogicDocument1 pageHistory of LogicLorelyn AbellanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 11-History of LogicDocument5 pages11-History of LogicAyele MitkuPas encore d'évaluation

- History of LogicDocument15 pagesHistory of Logicjoross-vidal-9468Pas encore d'évaluation

- Logical ProjectDocument14 pagesLogical ProjectNishant TyPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief History in LogicDocument2 pagesBrief History in LogicpanchojrPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1 - Introduction To LogicDocument6 pagesLesson 1 - Introduction To Logicmoury alundayPas encore d'évaluation

- Colegio de San Juan de LetranDocument2 pagesColegio de San Juan de LetranpanchojrPas encore d'évaluation

- Additional History of LogicDocument18 pagesAdditional History of LogicStef C G Sia-ConPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy of MathematicsDocument24 pagesPhilosophy of MathematicsASDPas encore d'évaluation

- The Upsand Downsof Analytic PhilosophyDocument14 pagesThe Upsand Downsof Analytic PhilosophyEmmanuel ServantsPas encore d'évaluation

- Raices Filosoficas Del Pensamiento Cientifico Rubén Alonso NegrínDocument38 pagesRaices Filosoficas Del Pensamiento Cientifico Rubén Alonso NegrínEstefania Andi0% (1)

- 1.1. History of Math LogicDocument2 pages1.1. History of Math LogicRandy Cham AlignayPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Mathematics & MATHEMATICIAN - Numerals and Numbers: Attic or Herodianic NumeralsDocument12 pagesGreek Mathematics & MATHEMATICIAN - Numerals and Numbers: Attic or Herodianic NumeralsMONHANNAH RAMADEAH LIMBUTUNGAN100% (1)

- Béziau, J. What Is Formal LogicDocument12 pagesBéziau, J. What Is Formal LogicRodolfo van GoodmanPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Western ThoughtDocument7 pages2 Western ThoughtAjay MahatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy 7Document3 pagesPhilosophy 7njerustephen806Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter TwoDocument16 pagesChapter TwoAyomipo OlorunniwoPas encore d'évaluation

- Meta-Narratives: Essays on Philosophy and SymbolismD'EverandMeta-Narratives: Essays on Philosophy and SymbolismÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- AMS The Lost RevolutionDocument5 pagesAMS The Lost RevolutionPraveen SelvarajPas encore d'évaluation

- A Very Short History of Western ThoughtD'EverandA Very Short History of Western ThoughtÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (3)

- Philo Homework Aug 17Document3 pagesPhilo Homework Aug 17Jerome Rivera CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosopy Basics - 4Document51 pagesPhilosopy Basics - 4JubeidaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Road To Modern Logic-An Interpretation: The Bulletin of Symbolic Logic Volume 7, Number 4, Dec. 2001Document44 pagesThe Road To Modern Logic-An Interpretation: The Bulletin of Symbolic Logic Volume 7, Number 4, Dec. 2001orfeu_nikoPas encore d'évaluation

- History and Theory Volume 3 Issue 3 1964 (Doi 10.2307/2504234) George H. Nadel - Philosophy of History Before HistoricismDocument26 pagesHistory and Theory Volume 3 Issue 3 1964 (Doi 10.2307/2504234) George H. Nadel - Philosophy of History Before HistoricismAlvareeta PhanyaPas encore d'évaluation

- If There Are Four Apples and You Take Away Three, How Many Do You Have?Document24 pagesIf There Are Four Apples and You Take Away Three, How Many Do You Have?Jefrie Marc LaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- A History of Medieval PhilosophyD'EverandA History of Medieval PhilosophyÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (5)

- Analytic Philosophy in America: And Other Historical and Contemporary EssaysD'EverandAnalytic Philosophy in America: And Other Historical and Contemporary EssaysPas encore d'évaluation

- History of LogicDocument12 pagesHistory of LogicnumeroSINGKO5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mathematical Realism and The Impossible PDFDocument26 pagesMathematical Realism and The Impossible PDFkronstadtPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific RevolutionDocument27 pagesScientific RevolutionMahaManthra100% (2)

- Ernan McMullin - Conceptions of Science in The Scientific RevolutionDocument34 pagesErnan McMullin - Conceptions of Science in The Scientific RevolutionMark CohenPas encore d'évaluation

- 18 Modules PhiloDocument31 pages18 Modules Philomaybe bellenPas encore d'évaluation

- Ferreirós, J. The Road To Modern Logic. An InterpretationDocument44 pagesFerreirós, J. The Road To Modern Logic. An InterpretationRodolfo van GoodmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Mathematics: Richell SanipaDocument57 pagesGreek Mathematics: Richell SanipaJemuel VillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy of Logic - Report TomDocument10 pagesPhilosophy of Logic - Report TomRazul Mike AbutazilPas encore d'évaluation

- Clashing Symbols Peter KreeftDocument7 pagesClashing Symbols Peter KreeftQuidam RVPas encore d'évaluation

- Eyers Tom Post Rationalism Psychoanalysis Epistemology and Marxism in Post War France PDFDocument224 pagesEyers Tom Post Rationalism Psychoanalysis Epistemology and Marxism in Post War France PDFweallus3100% (3)

- Logical Atomism and Logical PositivismDocument6 pagesLogical Atomism and Logical PositivismOgechi BenedictaPas encore d'évaluation

- History: History of The Social SciencesDocument2 pagesHistory: History of The Social SciencesJohn Kenneth BentirPas encore d'évaluation

- 19 Century German LogicDocument23 pages19 Century German LogictrelteopetPas encore d'évaluation

- Of Angels and MenDocument47 pagesOf Angels and Mengrw49Pas encore d'évaluation

- History of The Social Sciences - WikipediaDocument35 pagesHistory of The Social Sciences - WikipediaHanna Dee AlfahsainPas encore d'évaluation

- The Idea of Early Modern Philosophy: NUD AakonssenDocument24 pagesThe Idea of Early Modern Philosophy: NUD AakonssenbranemrysPas encore d'évaluation

- Sentences : Synthese 83: 273-292, 1990Document20 pagesSentences : Synthese 83: 273-292, 1990JijoyMPas encore d'évaluation

- Gale Researcher Guide for: The Scientific Revolution and the EnlightenmentD'EverandGale Researcher Guide for: The Scientific Revolution and the EnlightenmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Metaphysical Traces From A Radically HisDocument4 pagesMetaphysical Traces From A Radically HisEirini DiamantopoulouPas encore d'évaluation

- The Metaphysics of World Order: A Synthesis of Philosophy, Theology, and PoliticsD'EverandThe Metaphysics of World Order: A Synthesis of Philosophy, Theology, and PoliticsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Maths ProjectDocument67 pagesMaths ProjectRishika JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter FiveDocument50 pagesChapter FiveCharles MorrisonPas encore d'évaluation

- Bianco - The Misadventures of The Problem in Philosophy. From Kant To Deleuze 2018Document24 pagesBianco - The Misadventures of The Problem in Philosophy. From Kant To Deleuze 2018FEDERICO ORSINIPas encore d'évaluation

- Project of AbdullahDocument49 pagesProject of AbdullahGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 1415rfbDocument9 pages9 1415rfbGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Final Project Submitted To Mam Wajeeha HaiderDocument44 pagesMarketing Final Project Submitted To Mam Wajeeha HaiderGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hamza MGMT AssignmentDocument7 pagesHamza MGMT AssignmentGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing A New Venture's Financial Strength and Viability: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane IrelandDocument36 pagesAssessing A New Venture's Financial Strength and Viability: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane IrelandGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing An Effective Business Model: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane IrelandDocument28 pagesDeveloping An Effective Business Model: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane Irelandziafat shehzadPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing An Effective Business Model: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane IrelandDocument28 pagesDeveloping An Effective Business Model: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane Irelandziafat shehzadPas encore d'évaluation

- Pages From BroaddistinctionbetweenislamicconventionalDocument4 pagesPages From BroaddistinctionbetweenislamicconventionalGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump UpDocument1 pageJump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump Up Jump UpGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Case StudiesDocument4 pagesComparison of Case StudiesGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate GovernanceDocument25 pagesCorporate GovernanceGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Ethics Encompass The PersonalDocument18 pagesProfessional Ethics Encompass The PersonalGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Standards For AuditorsDocument5 pagesEthical Standards For AuditorsAlyssa LeePas encore d'évaluation

- LahoreDocument6 pagesLahoreGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Ethics Encompass The PersonalDocument18 pagesProfessional Ethics Encompass The PersonalGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Boutique Women Designer Wear PDFDocument30 pagesBoutique Women Designer Wear PDFGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Toys R Us ReportDocument14 pagesToys R Us ReportGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Ethics Encompass The PersonalDocument18 pagesProfessional Ethics Encompass The PersonalGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Toys R Us ReportDocument14 pagesToys R Us ReportGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Safe TechDocument14 pagesSafe TechGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Boutique Women Designer Wear PDFDocument30 pagesBoutique Women Designer Wear PDFGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate GovernanceDocument21 pagesCorporate GovernanceGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Montessori School Standardize Feasibility ReportDocument41 pagesMontessori School Standardize Feasibility ReportGhulam Mustafa75% (4)

- Quaid-E-Azam The Great LeaderDocument1 pageQuaid-E-Azam The Great LeaderGhulam Mustafa75% (4)

- Price Effects On Consumer Behavior - A Status Report by Jerry FDocument3 pagesPrice Effects On Consumer Behavior - A Status Report by Jerry FGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Montessori School Standardize Feasibility ReportDocument41 pagesMontessori School Standardize Feasibility ReportGhulam Mustafa75% (4)

- Corporate GovernanceDocument21 pagesCorporate GovernanceGhulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pro 1Document96 pagesPro 1Rukmini GottumukkalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Final 2Document19 pagesProject Final 2Ghulam MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Lettres Satprem ENG MainDocument26 pagesA Lettres Satprem ENG MainRabPas encore d'évaluation

- Webster School District Directory 2010-11Document32 pagesWebster School District Directory 2010-11timesnewspapersPas encore d'évaluation

- Nedley, N. (2014) Nedley Depression Hit Hypothesis: Identifying Depression and Its CausesDocument8 pagesNedley, N. (2014) Nedley Depression Hit Hypothesis: Identifying Depression and Its CausesCosta VaggasPas encore d'évaluation

- DLP-in-science (AutoRecovered)Document11 pagesDLP-in-science (AutoRecovered)Richard EstradaPas encore d'évaluation

- List of TablesDocument3 pagesList of TablesinggitPas encore d'évaluation

- Test DiscalculieDocument18 pagesTest DiscalculielilboyreloadedPas encore d'évaluation

- Preliminary Business Studies - Mindmap OverviewDocument1 pagePreliminary Business Studies - Mindmap OverviewgreycouncilPas encore d'évaluation

- Mar 3 Zad 4Document2 pagesMar 3 Zad 4Phòng Tuyển Sinh - ĐH. GTVT Tp.HCM100% (1)

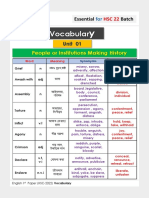

- Vocabulary HSC 22 PDFDocument28 pagesVocabulary HSC 22 PDFMadara Uchiha83% (6)

- Cheema CVDocument1 pageCheema CVhazara naqsha naveesPas encore d'évaluation

- Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook For Diagnosis and Treatment (4th Ed.)Document4 pagesAttention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook For Diagnosis and Treatment (4th Ed.)JANICE JOSEPHINE TJONDROWIBOWO 11-S3Pas encore d'évaluation

- D1 Collocation&idiomsDocument4 pagesD1 Collocation&idiomsvankhanh2414Pas encore d'évaluation

- Personality Development Reviewer PDFDocument6 pagesPersonality Development Reviewer PDFMikka RoquePas encore d'évaluation

- Final Exam in EappDocument4 pagesFinal Exam in EappCayte VirayPas encore d'évaluation

- Wellness Program ReportDocument5 pagesWellness Program Reportapi-301518923Pas encore d'évaluation

- Perdev Q2 Week 3 Las 1Document4 pagesPerdev Q2 Week 3 Las 1Demuel Tenio LumpaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 5 Freedom of The Human PersonDocument8 pagesLesson 5 Freedom of The Human PersonTotep Reyes75% (4)

- Week 1 SHort Essay - Ryan WongDocument2 pagesWeek 1 SHort Essay - Ryan WongRyan WongPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan Reading Year 2 English KSSR Topic 5 I Am SpecialDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Reading Year 2 English KSSR Topic 5 I Am SpecialnonsensewatsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Salma Keropok LosongDocument6 pagesSalma Keropok LosongPutera ZXeePas encore d'évaluation

- Challenges in Leadership Development 2023Document26 pagesChallenges in Leadership Development 2023Girma KusaPas encore d'évaluation

- Translation Poject IntroductionDocument31 pagesTranslation Poject IntroductionClaudine Marabut Tabora-RamonesPas encore d'évaluation

- War Thesis StatementsDocument8 pagesWar Thesis StatementsHelpPaperRochester100% (2)

- Social Cognitive TheoryDocument4 pagesSocial Cognitive TheorySheina GeePas encore d'évaluation

- The Biological Nature of Human Language: 1. Introduction: Background and OverviewDocument33 pagesThe Biological Nature of Human Language: 1. Introduction: Background and OverviewhalersPas encore d'évaluation

- English, Analogy-Paired Approach Part 4: Suggested TechniqueDocument39 pagesEnglish, Analogy-Paired Approach Part 4: Suggested TechniquecellyPas encore d'évaluation

- 534 - Verbs Test Exercises Multiple Choice Questions With Answers Advanced Level 35Document5 pages534 - Verbs Test Exercises Multiple Choice Questions With Answers Advanced Level 35Ana MPas encore d'évaluation

- The Care Certificate StandardsDocument13 pagesThe Care Certificate StandardsBen Drew50% (2)

- 5 ISTFP Conference: International Society of Transference Focused PsychotherapyDocument12 pages5 ISTFP Conference: International Society of Transference Focused PsychotherapyBessy SpPas encore d'évaluation

- ASYN Rodriguez PN. EssayDocument1 pageASYN Rodriguez PN. EssayNatalie SerranoPas encore d'évaluation