Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rony, Fatimah Tobing - Those Who Squat and Those Who Sit PDF

Transféré par

Ali AydinDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rony, Fatimah Tobing - Those Who Squat and Those Who Sit PDF

Transféré par

Ali AydinDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Camera Obscura

Figure 1. Modern print from an original chronophotographic negative, Woman

Walking with a Light Weight on Her Head (Charles Comte and Filix-Louis

Regnault, c. 1895, courtesy of the Cinimathtque Franiaise).

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

Those Who Squat and Those Who Sit:

The Iconography of Race in the 1895 Films

of Filix-Louis Regnault

Fatimah Tobing Rony

Explorers do not reveal otherness. They comment

upon “anthropology,” that is, the distance sepa-

rating savagery from civilization on the dia-

chronic line of progress.’

V.Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa

You are a Wolof woman from Senegal. You have come to Paris in

1895 with your husband as a performer in the Exposition Ethno-

graphique de 1’Afrique Occidentale (Senegal and French Sudan) be-

cause of the promise of good pay. You have been positioned in front

of the camera, and you are thinking about how cold it is: you can’t

believe that you have to live here in this reconstruction of a West

African village, crowded with these other West African people, some

of whom don’t even speak Wolof. Every day the white people come

to stare at you as you d o your pottery. You make fun of some of them

out loud in Wolof, which they don’t understand. You understand some

of their French; after all, you are from the port where there have been

French traders for as long as you can remember. Two men with

cameras have been filming you and others making pottery, grinding

grain, and walking. Right now, you have been told to walk straight

ahead carrying a container on your head.

You are the French physician Filix-Louis Regnault, and you are

behind the camera. Both you and your colleague Charles Comte are

using the chronophotographe, the camera invented by the physiologist

Etienne-Jules Marey intended for fast serial photography. Fascinated

by the new field called anthropology, you are delighted by this ethno-

graphic exposition at the Champs de Mars. Finally you can study the

movements of African people in the flesh-people you and other

anthropologists catalog as “savages”-instead of getting mere descrip-

tions of their movements from written accounts, photography, and art.

You are convinced that these chronophotographic documents will

elevate the new discipline of anthropology to the realm of science

[Figure 11.

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

264 In the scenario just described, the divide between observer and

observed appears to be clearly marked. The exchange of looks in the

film frames produced by Regnault, however, belies any simple polarity

of subject and object. There is, for example, a Frenchman, dressed in

a city suit and hat, who accompanies the woman as she walks, never

taking his eyes off her. His walk, meant to represent the urban walk,

is there as a comparative point of reference to what Regnault terms

the woman’s “savage” locomotion.2 He also acts as an in-frame sur-

rogate for the western male gaze of the scientist. There are also two

other performers visible at frame left, watching the Frenchman watch

the woman. Finally, a little girl, also West African, stares alternately

at the group being filmed and the scientist and his camera. She appears

to break a cinematic code already established in fin-de-siitcle time

motion studies: she looks at the camera. In this scenario of comparative

racial physiology, the little girl has not learned how properly to see or

be seen. At the nexus of this exchange of looks is the Wolof woman.

She, however, is not the agent of a look. Rendered nameless and

faceless, it is her body that is deemed the most significant datum: she

is doubly marginalized as both female and A f r i ~ a n . ~

This description of the chain of looks is taken from chronophotogra-

phy by the physician Filix-Louis Regnault, a series of time motion

studies considered by many to be the earliest example of ethnographic

film.4 The images are artifacts of a time when medical doctors in the

name of science were feverishly engaged in narrativizing human history

as a linear evolution from darker to lighter-skinned peoples. This

fascination with race characterized much of early cinema and remains

prevalent today. It is no coincidence that issues of race are as essential

to popular films such as D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of the Nation

(1915),as to documentaries such as Robert Flaherty’s Nunook ofthe

North (1922). Cinema was, and is, intimately linked with the evolu-

tionary ideology that posits race as the predominant means of explain-

ing human difference.

Although Regnault’s images have been largely ignored by film his-

torians, visual anthropologists eager to establish a lineage for their

endeavors now claim Regnault’s films as precursors.’ Like much of

what is now termed early “ethnographic” cinema, Regnault’s films

seem to have no narrative. I contend, however, that there is a narrative

implicit in these films, a narrative which, in fact, is implicit in ethno-

graphic film.6 The narrative is that of evolution.

This essay is thus about “seeing” anthropology. Johannes Fabian

argues convincingly that anthropology situates the people that it stud-

ies in the “there and then,” in spatial and temporal dimensions distinct

from the present time of the anthropologist. He explains that anthro-

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

pology is premised upon naturalized and evolutionary time; moreover, 265

anthropology has an inherent visualist bias, categorizing indigenous

peoples by way of taxonomic tableaus.’ My aim here is to show how

the emergence of cinema is critically linked with the emergence of

anthropology and its visualizing discourse of evolution.

The article is divided into three parts. In the first part, I describe

how the visualism of nineteenth-century anthropology inspired

Regnault’s use of film. In the second part, I examine popular repre-

sentations of people constructed as “ethnographic” (those considered

to be without technology and without history) at the turn of the

century, focusing on the ethnographic exposition that so enthralled

Regnault. I argue that in representing race, the scientific imagination

merged with the popular. In the third part, I examine Regnault’s

conception of film as the ideal positivist scientific tool for recording

movement. In Regnault’s films, as in ethnographic film generally, the

viewer is confronted with images of people who are not meant to be

seen as individuals, but as specimens of race and culture, specimens

that provide the viewer with a visualization of the evolutionary past.

Although the Wolof woman and the Frenchman walk within the same

space in the above example, they are made distant from each other

both spatially and temporally by science and by popular culture.

1. The Scientific Invention of Race: Visualizing Evolution

In his chronophotography as well as in his huge output of writings

on medicine, anthropology, prehistory, sociology, history, zoology,

and psychology, Regnault was obsessed with the body and with evo-

lution. Regnault, in other words, was one of many late nineteenth-cen-

tury physicians fascinated by the emerging discipline of anthropology.*

Race was the defining “problem” of this new discipline.’ The present-

day breakdown of anthropology into physical anthropology and cul-

tural anthropology (ethnography being the principle tool of the latter)

did not strongly emerge until the mid-twentieth century: in the nine-

teenth century, racial heredity was believed to determine culture. As

George W. Stocking, Jr. writes, physical human variety was interpreted

“in regular rectilinear terms as the result of differential progress up a

ladder of cultural stages (savagery, barbarism, civilization) accompa-

nied by a parallel transformation of particular cultural forms (poly-

theisdmonotheism; polygamy/monogamy).”lo For Regnault, the

physiological aspects of how a Wolof woman made a pot, as well as

the pot itself, were elements of an evolutionary narrative of human

development.

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

266 In France, the most important anthropological organization was the

SociCtC d’Anthropologie de Paris, of which Regnault was a member.

The SociCtC was founded by the biologist Paul Broca in 1859, the same

year that Darwin’s The Origin of Species was published. A positivist

zeal for the physical description, measurement, and classification of

racially defined bodies was the driving force of anthropology at the

SociCtC. Since it was thought that brain weight correlated with intelli-

gence, and since it was often impossible to study the human brain

itself, craniology, the study of cranial measurements, came to be

considered the most important aspect of racial studies.

The desire to demarcate difference and the quest to describe the

body according to racial types coincided with the rise of imperialism

and nationalism: the discourses of race, nation, and imperialism were

intimately linked. Anthropology legitimized imperialism through its

“scientific” findings that indigenous nonEuropean peoples were infe-

rior and at the bottom of the evolutionary ladder of history.” The link

between anthropology and imperialism was strengthened by

anthropology’s voracious need for data. Until 1926, with the founding

of the Institut d’Anthropologie under Marcel Mauss, anthropologists

were not required to have actually gone to the field and “been there.’’

These “armchair anthropologists” depended on the reports of mission-

aries, travelers, and colonial physicians, as well as museum and learned

societies’ collections of skulls, maps, and photographs. Eager to acquire

more standard data to legitimize itself as a true science, the SociCtC

d’Anthropologie de Paris published a manual to be used by colonial

officers and travelers for measuring crania and reporting anthropolog-

ical descriptions. In this SociCtC manual, Broca made an analogy

between the anthropological subject and the sick patient:

Just as the best description of a malady is that which rests on a series of

observations taken singly and written by the bed of a sick man, so the best

description of a race rests on a series of individual descriptions, written at

the time of meeting, in the presence of a subject whom one is observing

without any preconception to investigate one particular fact. l2

This passage provides a particularly striking example of how the lens

that anthropology focused on colonial subjects was profoundly in-

formed by the nineteenth-century discourse on medicine and pathol-

ogy. This is not surprising: the average member of the SociCtC

d’Anthropologie de Paris was, like Regnault, a physician. However, it

was precisely the construction of the “pathological” against which

anthropology constituted its Western subject as “ n ~ r m a l . ” ’ ~

The concept of “race” was never fully scientifically validated. Even

though Regnault and other anthropologists energetically sought out

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

the perfect index to measure and classify race, prominent anthropol- 267

ogists James Prichard and Paul Broca both admitted to the constructed

nature of race, as did their predecessor, Count Buffon. After thousands

of skulls had been measured and endless statistical analyses performed,

no one could agree on what race was or how to measure it. If “race”

could not be scientifically proven, however, the narrative of racial

difference with its evolutionary premise proved ideologically powerful.

The narrative was repeated and consumed in a deluge of late nine-

teenth-century visual technologies displaying the body of the “Primi-

tive,” in the form of museum collections of skulls, dioramas with wax

or plaster figures, photography, expositions, and film. Both anthro-

pology, infused with the taxonomic imagination of natural history,

and popular culture, as I will show later, incessantly visualized race.

Regnault’s writings provide ample examples of this visual obsession:

he saw evidence of race and the pathological in virtually every visual

medium conceivable. At first, Regnault embraced craniology as the

supremely objective method to understand the body. In his thesis of

1888 on cranial deformations in rickets patients, Regnault praised

Broca’s method of craniology for its mathematical exactitude, one that

eliminated “le facteur personnel.” l4 Besides crania, Regnault diagnosed

the body through art. Regnault even insisted on the descriptive truth

of art, using it as evidence of evolutionary mental development as well

as physical posture and movement.’’ Each race, he believed, has a

predominant and particular posture when at rest and when in motion:

he could thus “see” race in art.16 In his evolutionary study of the

development of body posture, a study he would later call anthro-

pographie or physiologie ethniques comparkes, he traced mankind

from the Savage, who squats, kneels, carries loads, and climbs trees in

specific ways, to the Civilized, who sits in chairs.” Everywhere, he saw

visual clues to race and evolutionary development. For Regnault, the

Savage not only squats as children do, he represents the “childhood”

of Civilized man’s “adulthood.”18

In studying race and evolution through crania, art, photography and

so on, Regnault found one essential ingredient missing-movement.

The surgical eye could dissect the corpse but could not understand

how it moved. In searching for an index for race-the unfashioned

clue-Regnault chose to explore movement, that which is “in between”

culture and nature, acting and being. In the eyes of French anthropol-

ogists, the movement of the Savage was pathological. For example, L.

Bkrenger-Fkraud, the chief medical officer of Senegal, wrote that it

appeared to be more natural for Wolof women to walk on all fours

due to the angle of their pelvic and backbones. He also stated that the

big toes of Africans were large and more capable of independent

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

268 movement (thus prehensile like monkeys), as did Regnault.” If we

relate such ideas about the “animality” of West African movement to

Regnault’s films, we can begin to place Regnault’s films in the context

of a knowledge system whose paradigm was relentlessly racist and

relentlessly comparative. As his colleague at the Sociktk d’Anthro-

pologie de Paris, Charles Letourneau, put it:

In spite of its imperfections, its weaknesses and vices, the white race, semitic

and indo-european holds, certainly for the present the head in the “stee-

plechase” [sic] of human groups.20

The “steeplechase” is an important metaphor. History was a race:

those who did not vanquish would vanish. It is significant, therefore,

that Regnault would use film to record the movements of the perform-

ers he observed at the ethnographic exposition: film would inscribe

race (human difference) and would be evidence of history (which was

also a race). Time was thus conceived in evolutionary terms, with race

as the key factor, and the body as the marker of racial difference.

However, the study of bodies in themselves was not enough: how

people moved and interacted in their environment was essential, and

such environments were reconstructed for both the scientist and the

public in popular late nineteenth-century ethnographic exhibitions.

2. Spectacular Anthropology: Popular Representations of Race

The public ends up ignoring written accounts of

purely intuitive doctrines, they prefer studies

which are well documented, even if these studies

do not end with a precise conclusion.

Filix-Louis Regnault,

L’Euolution de la prostitution

In his search for ways to capture movement it is not surprising that

Regnault, like other anthropologists, frequented popular entertain-

ments such as fairs, museums, and zoos where native peoples per-

formed at the turn of the century. These popular entertainments were

not only sites of spectacle but laboratories for anthropological inves-

tigation. In 1895, Regnault wrote an ecstatic account of what he saw

at the Exposition Ethnographique de 1’Afrique Occidentale located at

the Champs de Mars, Paris [Figure 21:

I am aware that I could not observe everything. A thousand details, a

thousand particularities would require a volume.

Yes, this is the true ethnographic exposition. No one has adorned savages

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

Figure 2. Illustrations accompanying Regnault’s “Exposition Ethnographique de

1’Afrique Occidentale au Champs-De-Mars a Paris. Shegal et Soudan Franqais,”

La Nature 2.3 (17 August 1895): 185.

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

270 with ridiculous costumes, and no one has taught them a role in advance.

These negroes live as they do in their country, and their customs are

faithfully respected, easy to see.

May this exposition serve as a model for future expositions!2’

“A thousand details,” Regnault exclaimed. And, indeed, the exposi-

tions were full of details: at the 1895 exposition great efforts were taken

to recreate the imagined environment of Senegal and the Sudan. There

were 350 African performers living on a set made to look like a Sudanese

village with thick walls, dirt walled houses, and straw huts. People

worked as tanners, weavers, potters, and pipe makers; others were

musicians; and families sitting in front of their houses cooked in the

open air.u Events like religious ritual performances, sheep sacrifices,

and a human birth and a marriage were advertised in the newspaper^.^^

A horror uacui was revealed at the exposition: every space was

crammed with costume, animals, vegetation, and architecture. At the

same time that the exposition was a site of excess, it was also a place

of spectacle where detail was ordered, classified, and rationalized. The

ethnographic exposition framed the reading of race in what was above

all a reconstruction: the different ethnic groups at the fair were archi-

tecturally divided in an encyclopedic fashion, and there was a tendency

to group the “villagers” in nuclear family units, Noah’s A r k - ~ t y l e . ~ ~

The “native village” was one of the many visual technologies like

the natural history museum, the carte de uisite, the colonial postcard,

and even the zoo that exhibited humans, that reassured the Western

public about the reality and localization of the “Savage.” These pur-

portedly authentic reconstructions of the indigenous village began in

France in 1877 at the Jardin d’Acclimatation, and later became a

regular feature of the world’s fairs, beginning with the Exposition

Universelle in Paris in 1889. In this positivist age, it was felt that bodies

could teach the masses about empire, science, technology, nation, as

well as about family and racial hierarchies. It was no coincidence that

the most popular of all the “native villages” in the 1880s and 90s, the

period of great imperial French expansion in Senegambia, western

Sudan, and the west coast of Africa from Senegal to Gabon, were the

reconstructed villages of the Dahomeyans and Senegalese.2s Part

human zoo, part performance circus, part laboratory for physical

anthropology, ethnographic expositions were meaning machines that

helped define what it meant to be French as well as what it meant to

be West African in the late nineteenth century.26

As Regnault commented, the ethnographic exposition was the site

of proliferating details. In fact the details, in part, defined the concept

of ethnography itself. The word “ethnography” was first used in the

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

1820s in conjunction with geography, and denoted the study of peoples 271

and their relation to the environment, thus embodying the idea that

one could map human groups just as one maps mountains and river^.^'

By the late nineteenth century, in the popular imagination, the word

“ethnographic” had taken on the connotation of “exotic” and “pic-

turesque.” In art, the “ethnographic” manifested itself in a genre called

“la peinture ethnographique,” which referred to painting so detailed

that it seemed to portray the scientific observation of “exotic” customs

(Jean-Lion GCrGme, with his photographic-like detail, was a master

of this genre).28Likewise the use of the term exposition ethnographique

conjured up an image of overabundant detail set forth in photographic

clarity such as those contained in Gir6me’s paintings of slave markets

and snake charmers. The “ethnographic” for both science and popular

culture evoked the image of the encyclopedic tableau vivant depicting

the life of indigenous peoples.

The ethnographic detail coalesced in the spectacularizing construc-

tion of the “ethnographic.” Detail is meant here in three senses. The

first sense is detail as document: Regnault writes of the exposition as

the site of authentic scientific detail. The second sense is detail as

ornament. A good example of this notion was outlined in Adolf Loos’s

“Ornament as Crime”: exotic, ornamental detail was aligned with

decadence, the criminal element, and the Savage.29 The third sense is

detail as index; the anatomical and physiological details of the body

became the classificatory index of race both for anthropologists and

for viewers of ethnographic spectacle.

The work of defining and establishing boundaries between science

and fantasy, truth and fiction, was a major theme in almost all of

Regnault’s writings, and he looked to detail to distinguish the authentic

from the unauthentic. Detail also promised to flesh out the classifica-

tory outline of race.3o In his review of the 1895 ethnographic exposi-

tion, Regnault began by painstakingly describing the different physical

and cultural details of the various ethnic groups at the fair. Immediately

following this lengthy description of ethnic differences, however, he

again invokes the idea of race: he calls the performers “nitgres.”

Difference is articulated, only to be erased by use of the flattening label

“nitgre.” He refers to all the performers, moreover, including those of

Arab ethnicity, as black and ~hildlike.~’ Detail, which possibly could

have led to an understanding of cultural differences, is subsumed by

the ideology of race.

The way in which Regnault distances himself from the performers

when he invokes the anthropological rhetoric of race is indicative of

an extraordinary version of “us versus them” mentality. This mentality

was reinforced at the exposition in the form of voyeurism, and sanc-

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

272 tioned simultaneously by scientific knowledge, the evolutionary para-

digm of history, and the imperialist imperative to civilize. The visitor

was in a sense invited to act as a scientist and colonialist, to acquire

knowledge by looking at the body and its habitat. He was also invited

to engage in sexual voyeurism: the exhibition was the site for the

viewing of the unseen. Regnault, for example, described the

Dahomeyan women at the 1893 exposition as seductive: “In their

youth, they are sometimes seductive with their soft, timid and laughing

p h y s i ~ g n o m y . ”Moreover,

~~ Africa and other colonized lands were

often portrayed as Woman in imperialist discourse: eroticism, imperial-

ism, and anthropology were aligned.33

Just as the boundaries of science and popular culture seem to have

been permeable at the fair, boundaries between the observer and the

observed, that is, the exposition performer, were also blurred. The

“fence” was physical as well as psychological: a railing separated the

performers from the visitors, and this railing probably went around

the “villages,” allowing the crowds to gather for special performances.

Looming above the scene was the Eiffel Tower, the ultimate sign of

French technology, progress, and power. The exposition layout also

included a mosque (where nonMuslims could not enter) and a brasserie

(where visitors could mix freely with performer^).^^

The inclusion of the brasserie suggests that the voyeurism of the

exposition was imperfect: spectators could be made aware that the

performers had eyes and voices too. Consider, for example, the space

of interaction between visitor and performer at the fair. Ordinarily, a

fence physically divided the West African performers and the French

visitors, setting up a clear distinction between subject and object,

colonizer and colonized, viewer and viewed. At the brasserie, however,

the boundaries were permeable and interaction was allowed. An ex-

ample of this interaction is found in a review of the 1893 Dahomeyan

Ethnographic Exposition in which Regnault recalled asking a per-

former why there were different shades of skin color among the

Dahomeyans. The answer he received was a question: “Why . . . are

some of you brown-haired, others blond, still others redhead^?"^^ The

answer Regnault received is like a reflected mirror, revealing that the

purported objects of study-the Dahomeyan performers-were also

observers of the French.

The presence of the brasserie suggests what I believe is a more

general theme: part of the fascination that the public had for the fair

was the play with boundaries that it facilitated. First, even as the

exposition strived to construct and address clear subjectivities, and

even as the “picturesque,” the “ethnographic,” and the “detail”

reigned in the arena of spectacle, there were marginal spaces at the

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

fair where one could “straddle the fence”: the viewed could also remark 273

upon the French body, there were places where the “specimens” could

not be viewed at all (the mosques), and the very act of voyeurism was

undermined by the constant haranguing by the performers for “un

SO US.''^^ Second, since constructions of the Ethnographic or Savage

embodied all that was taboo to Western society-nakedness, polyg-

amy, fetishism, and cannibalism-white visitors could view at the fair

all that was forbidden, flirting with the boundaries of Self and Ethno-

graphic Other, while at the same time maintaining a distance. The

Ethnographic body also represented biological danger, that which must

be attacked in its very ~orporeality.~’ That threat could be contained

by racial visualization.

The narrative of evolution that slots humans in color-coded catego-

ries, placing the white race at the lead, was scientifically illustrated

through the live, dead, and skeletal bodies of indigenous nonEuropeans

displayed at fairs and museums. History is obfuscated: the native is

shown as being without history, and is described in terms borrowed

from zoology. The history of the circulation of African bodies as

enslaved persons, and the histories of the entwinement of French and

West African politics and economics is erased, replaced by another

form of circulation, that of anthropological spectacle.

Yet there was also the fear of degeneration, fear that the white man

had reached the pinnacle with nowhere to go but down. The “native”

was perceived by science and by popular culture as authentic man,

closer to nature: Regnault, as I explain in the next section, used his

films of West Africans, who were seen as hardier and more agile, in

order to improve the French military march. The Ethnographic was

both biological threat and example of authentic humanity: both aspects

would be essential to cinema’s form of visualizing anthropology.

When the exhibiting of “native villages” was discontinued due to

prohibitive cost, world wars, and the end of imperialism, cinema took

over many of its ideological functions. Cinema, after all is a much less

expensive way of circulating nonwestern bodies in “situ” than is

circulating reconstructed “villages.” Early cinema showed a fascination

for the subject of indigenous, nonEuropean peoples in its proliferation

of travelogues, scientific research films, safari films, scripted narrative

films, and colonial propaganda films. Like ethnography, cinema is also

a topos for the meeting of science and fantasy. Cinema also eliminated

the potentially threatening return-gaze of the performer, offering more

perfect scientific voyeurism. Films about the “customs and manners of

the peoples of X” emphasized the family unit and habitat, as the fair

did. The fence of the fair was now the movie screen, and the subject

positioning of the European viewer was reaffirmed. Finally, cultures

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

274 were presented as encapsulated “villages” on film, making ethno-

graphic film, like the ethnographic fair, a superb time machine, inviting

the viewer to travel spatially and temporally, back in evolutionary time

to the “childhood” of modern white man.38

3. The Writing of Race in the Films of Regnault

You can divide humanity into those who squat

and those who sit.

Marcel Mauss, “Les Techniques du corps”

Regnault believed that film was destined to become the ideal positivist,

scientific medium for the study of race. If the fair was the site for

regimenting proliferating ethnographic detail, film was the site where

ethnographic detail could be recorded, magnified, dissected, and re-

played for posterity. Regnault declared:

Cinema expands our vision in time as the microscope has expanded it in

space. It permits us to see facts which escape our senses because they pass

too quickly. It will become the instrument of the physiologist as the micro-

scope has become that of the anatomist. Its importance is as great.39

Regnault’s search for a representational medium that was truly

indexical, one which could capture the body in the fullness of move-

ment, lay behind his interest in live observation at the ethnographic

exposition as well as his interest in and use of film.

We have seen how evolution informed Regnault’s ideas about the

body and movement. The authenticity of the ethnographic exposition,

despite the fact that it was in Paris, was absolute for Regnault, and

this in large part has to do with the fact that he was enthusiastic about

the availability of people to study. For it was the body that was

authentic. Regnault would capture it and inscribe it onto film for future

scientific readers.

For Regnault, film offered not only an improved means of getting

to an index-he thought that the races reveal themselves in movement,

and felt that film could assist him in the study of movement-but a

medium that was also by its nature indexical: like a footprint, film is

a document, testifying that the person filmed had passed in front of

the camera lens. To quote Roland Barthes, film contains “an emana-

tion of the referent.”40 Regnault proclaimed cinema the ultimate ap-

paratus for positivist science:

It provides exact and permanent documents to those who study movements.

The film of a movement is better for research than the simple viewing of

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

movement; it is superior, even if the movement is slow. Film decomposes 275

movement in a series of images that one can examine a t leisure while

slowing the movement at will, while stopping it as necessary. Thus it

eliminates the personal factor, whereas a movement, once it is finished,

cannot be recalled except by memory, and this, even put in sequence is not

faithful. All in all, a film is superior to the best description^.^^

It is astonishing how similar this description of film is to Regnault’s

1888 description of craniology. Both technologies are precise, scien-

tific, and eliminate subjective factors. But film is superior even to

craniology: it captures movement. Moreover, unlike the eye, which

fuses successive images, film decomposes movement, and the camera

can capture rapid movements that the eye cannot see.42

Regnault filmed West African and Malagasy men, women, and

children from ethnographic exhibitions, usually alone and in profile,

walking, running, jumping, pounding grain, cooking, carrying children

on their backs, and climbing trees. The tableau of the fair and

Regnault’s own fascination with movement are inscribed into film,

representing scenes that would become the staple for later ethnographic

film. Most of the films that were not exclusively of walking and

running were made on location at the ethnographic exposition: the

setting was an important signifier of authenticity. Filming the move-

ments of a West African performing a task-such as making pottery-

allowed the scientist, according to Regnault, to go back in time, to an

evolutionary origin of pottery.43

Regnault believed that those he called Savage had no language, and

instead spoke through the body in what he called le langage par gestes.

A person of North Sumatra, he wrote, could speak to a Dahomey in

West Africa through this universal language of the body. The gesture,

wrote Regnault, was more important to the “inferior” races than to

so-called Civilized man. The language that film could inscribe was

therefore the language of gestures:

It appears, moreover, unusual to affirm that there exists a science of

gesture as interesting as that of language. However all savage peoples make

recourse to gesture to express themselves; their language is so poor it does

not suffice t o make them understood: plunged in darkness, two savages, as

travelers who often witness this fact affirm, can communicate their

thoughts, coarse and limited though they are.

With primitive man, gesture precedes speech . . . .

The gestures that savages make are in general the same everywhere,

because these movements are natural reflexes rather than conventions like

language. 44

Gesture precedes speech. Thus humanity was divided into not only

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

276

Figure 3. Modern print from original chronophotographic negative, Jump By

Three Men (Charles Comte and Ftlix-Louis Regnault, c. 1985,

courtesy of the CinCmathtque FranCaise).

those who sit and those who squat, but those who have language and

those who gesticulate. In many films, the subjects are rendered as mere

silhouettes, pictographs of the langage par gestes. Their faces are

unimportant: it is the body that is the necessary data. And thus

Regnault writes, the “savage” has no real language: the scientist will

inscribe his language-a language par gestes common to all “sav-

ages”-into film. They become hieroglyphs for the language of science:

race is written into film.

In Regnault’s films, bodies are made abstract and mechanized. Detail

is very well-managed. The subjects enter the frame at right and exit

at left, often with a chronometer in front and a white screen in the

back [Figures 3 and 41. The fact that Regnault filmed movements from

different perspectives-the subject is seen from the right, then left, and

then back-reflects the codes of anthropometric photography that

were already well established in the late nineteenth century. For films

of walking and running, Regnault and his colleague Charles Comte

often used a chronometer and a painted scale on the ground to measure

the duration of the subject’s step. Diagrams translating the movements

into oscillating curves were used to test the efficacy of the marche en

flexion, a gait in which one ran o r walked with knees greatly bent, the

body leaning forward in “la marche primitive de l ’ h ~ m a n i t k . ’ ’The

~~

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

use of the chronometer, the painted scale at the bottom of the film, 277

and the tightly controlled entrance and exit of each moving subject

attests to Regnault’s belief that chronophotography was a mathemat-

ical and scientific means of studying movement. The camera maintains

a distance, and yet observes from all angles.

Regnault also filmed French military officers walking, running, and

climbing trees. The link between Regnault’s films of French military

officers and those of West Africans is Regnault’s claim that the walk

of the Savage was en flexion-with torso bent forward and knees

Figure 4. Modern print from original chronophotographic negative, Run

(Charles Comte and FClix-Louis Regnault, c. 1895,

courtesy of the CinCmathtque Franiaise).

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

278

Figure 5. Illustration by Regnault for his “Le

r6le du cinkma en ethnographie,” La Nature

2866 (1 October 1931): 304. The man seated

in the palanquin is Regnault.

greatly bent-akin to the marche en flexion, a walk that the French

military commandant De Raoul had first espoused for the French

military. Regnault wrote numerous articles on the marche en flexion,

as a means to ameliorate the French military walk. The portrayal of

Westerners, however, generally contrasts sharply with the portrayal of

the West African performers. For the discourse on the “ethnographic”

was linked to that of the National Body: the “ethnographic” repre-

sented a purer, authentic, and healthier man than the overstimulated,

nervous, and weakened modern white urban citizen.46

In the films of West Africans, the bodies often are rendered as

shadows. Wearing tight long suits or just shorts, these men do not

look up and acknowledge the presence of the camera: they are often

filmed in such a way that they are turned into ciphers, their faces

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

indistinct. Although the performers walk in the foreground, they often 279

appear to be behind a screen, like shadow puppets. If we compare

these films of West Africans to one of a French man running, we see

that the costume and mise-en-sche are different: the French subject is

dressed in a suit and beret, and is shown running with large steps; his

clothes, body, and face are clearly filmed. His body is substantially

rendered.47

Racial identity is also signified by who gazes at whom. Performers

d o not look at the camera, but the gaze of the scientist is often

acknowledged, if sometimes inadvertently. In two examples, a tall man

in shorts walks from right to left, but the lighting is such that his body

is so dark it becomes a silhouette. On closer examination, however,

one sees a man in a suit, possibly Regnault or an assistant, behind the

screen that serves as the films’ background. The reader of the film is

thus provided with a mirror image: he or she is also in the position of

the s ~ i e n t i s t . ~ ~

In another example, Regnault himself waves at the camera as he is

carried in a palanquin by four Malagasy men [Figure 51. The image

of the French colonizer in a palanquin was a ubiquitous one, especially

in 1895 during the colonization of Madagascar by the French. This

particular film was used as evidence for Regnault’s theories on the en

flexion gait, which he thought to be the natural walk of Savages.

Regnault the scientist tips his hat to the camera, and to the viewer: he

tips his hat to his own power to record these movements of recently

colonized people on film, while the men whose movements are filmed

do not look into the camera. The scientist is both colonizer and

researcher.

In the film entitled “Docteur Regnault marche” [Figure 61, however,

we see a rather unassuming man, head down, wearing a body suit,

whose features are as hard to identify as those of any of the West

African subjects. Cinematically there is little difference between this

example and that of a West African man walking: the scientist himself

has become a specimen. The ideological difference of course is that we

know Regnault’s name and biography; he is not rendered into a

nameless specimen of some anthropological category known as the

Negro or the Savage. Thus the textual accompaniment of the film is

absolutely essential to the interpretation (as were explanatory inter-

titles, and the authoritative voiceover in later ethnographic film).

Although anthropology clearly emphasizes the practice of observa-

tion-the anthropologist observes the cultures of indigenous peoples-

it is above all a signifying practice that deals with words and narrative1

strategies to convince the reader of its ethnographic authority. Images

however are a little more slippery: although the image must contain

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

280

Figure 6. Modern print

from original

chronophotographic

negative, Doctor Regnault

Walks (Institut de

Physiologie, c. 1895,

courtesy of M. Eric Vivi6

and the Archives du Film).

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

visual signifiers of authenticity, captions are still often needed to 281

explain, convince, and keep order.

Finally, Regnault was one of the first to envision an ever growing

archive of ethnographic images. This vision reflects the anthropological

conceit that the anthropologist can thwart death and time: he can

record vanishing ways of life and store them in his drawer for future

study. Regnault believed that cinema would one day fulfil Auguste

Comte’s positivist dream: cinema would provide unmediated records

of reality for scientific consumption. For Regnault, cinema was supe-

rior to observation, enabling the anthropologist to dissect, replay, and

review movement at will. Hence the importance of the archive to

Regnault. With the film archive, the scientist proclaimed himself or

herself fully in control over time and the image, able to call up

comparisons of movements, techniques, and rituals at will. Regnault’s

model for the archive, however, was not the all-encompassing, alpha-

betically organized encyclopedia, but the topically organized mu-

s e ~ r n .Regnault

~~ was also one of the first to advocate that

ethnographic museums use film and phonograph recordings to aug-

ment and legitimize their material collections. He was probably greatly

influenced in this regard by his SociCtC d’Anthropologie colleague Lion

Azoulay who created one of the first archives of phonograph records

in the ~ o r l d . ~Like

’ the ethnographic exhibition which presented peo-

ples in orderly reconstructed village tableaus, the ethnographic film

archive is a visualizing technology for the taxonomic ranking of peo-

ples.

4. Conclusion

“Amnesia, Error, Indifference, Omission, Uncivil”-subverting the

writing of race is powerfully manifested in the work of certain con-

temporary artists of color like the African-American photographer

Lorna Simpson [Figure 71.” I began this essay by showing how the

“ethnographic” in film works to deny the voice and individuality of

the indigenous subject. The performers in Regnault’s films are meant

to represent not only a typical West African body, but a body typical

of what anthropology called Primitive. Their names and history are

not given: the fact that they are performers from a fair, the colonial

nature of France’s relation to West Africa, etc. Emptied of history,

their bodies are raciafized. The raciafized body in cinema is a construc-

tion denying people of color historical agency and psychological com-

plexity. Individuals are read as metonyms for an entire category of

people, whether it be ethnic group, race, or Savage/Primitive/Third

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

282 World. Regnault is both informed by and informs the scientific and

popular circulation of the image of the “ethnographic. ’’ Thus scientific

cinema teaches us how to read bodies: the “ethnographic” squats,

climbs trees differently, carries the colonialist in a palanquin, performs

animal sacrifices, and goes about her affairs bare-breasted. A similar

iconography of race is at work in the construction of Hollywood

cinema stereotypes like the black Mammy or the Chinese dragon lady,

but the racialization that occurs in ethnographic film is particularly

pernicious because it is “scientifically” legitimized, and the subjects of

the film are tied to the evolutionary past.

Figure 7. Mixed art piece, Easy For Who To Say (Lorna Simpson, 1989,

courtesy of the Josh Baer Gallery).

But racialization is not necessarily the product of contempt. Notions

of the native as pathological and savage often coexist with images of

the “noble savage”: Regnault himself believed Europeans to be in

danger of becoming suraffinb, too refined, and he used his films of

West Africans to support his theory that the marche en flexion was

more natural, a healthier way to walk. Whether portrayed as savage,

noble, or simply authentic, however, the “ethnographic” is a product

of the taxonomic imagination of both anthropology and cinema.

What lends ethnographic film its aura of truth is thus the Ethno-

graphic body, coded since Regnault’s time as authentic. Moreover,

these films could not only be used for research into race and evolution,

but to improve the productive body of the capitalist and imperialist

European world: Regnault used films of West Africans to improve the

French military walk. One use value of Regnault’s work was thus war.

In an ironic twist, beginning in World War I, many West African men

were recruited into the French army to serve as the now-famous

tirailleurs. Their bodies were again used, this time as the infantrymen

for French battles. Accordingly, I would like to conclude by going from

one camp-the 1895 Exposition Ethnographique where Regnault

made his films-to another camp-the transit camp for West African

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

tirailleurs returning home to Africa depicted in SembZne Ousmane’s 283

and Thierno Saty Sow’s film Camp de Tbiaroye (1987).

In Camp de Tbiaroye, as in Regnault’s films, almost all of the

principal characters are West African. Unlike the performers in

Regnault’s films, however, they are given names, history, psychological

complexity, and agency. These soldiers, like colonized peoples in other

parts of the world, return from World War I1 battles and concentration

camps having learned one very important lesson: how small France is.

Their profound consciousness that “a white corpse, a black corpse,

it’s all the same” leads to their explosion against their oppression as

colonial subjects. It is clear therefore that what distinguishes the genre

of the “ethnographic film” from a film like Camp de Thiaroye is not

the color of the people filmed, but how they are racialized-how, in

other words, the viewer is made to see “anthropology” and not history.

NOTES

This article is a condensed version of a section of my doctoral dissertation,

and a version of a paper delivered at the Pembroke Center for Teaching and

Research on Women. I am grateful to the Pembroke Center and roundtable

participants for their comments and suggestions.

Research for this article was made possible by grants from the Council for

European Studies, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the Yale Center for

International Area Studies, and the American Association of University

Women. I thank M. Eric Vivii, the Archives du Film du Centre National de

la Cinimatographie, the Cinimathkque FranCaise, and the Josh Baer Gallery

for permission to reproduce images.

I am indebted to Jean Rouch for his generous aid and advice. I also would

like to thank the following people: Noelle Giret, Vincent Pinel, Alain Marc-

hand, and the late Olivier Meston of the Cinimathkque Franqaise; Michelle

Aubert, Andrei Dyja, and Eric Le Roy of the Archives du Film; Franqoise

Foucault of the Musie de 1’Homme; Jean-Dominique Lajoux of CNRS. I would

especially like to thank Lisa Carnvright, Angela Dalle Vacche, Emilie de

Brigard, and Faye Ginsburg. My views may diverge from those who have

helped me; I take full responsibility for all errors.

1. V.Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy and the

Order of Knowledge (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University

Press, 1988) 15, from citation in R. I. Rotberg, Africa and Its Explorers

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970).

2. Filix Regnault and Cdt. de Raoul, Comment on marche: Des divers mode

de progression de la supe‘riorite‘du mode en flexion (Paris: Henri Charles-

Lavauzelle, Editeur militaire, 1897). Illustration of man reproduced on p.

23.

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

284 3. There is a strong tendency in some of the recent postcolonial criticism of

the representation of nonwestern peoples in literature, popular culture,

and science to ignore the subjectivities of the people represented as “Prim-

itive,” “Savage,” “Negro,” and/or “Oriental.” I do not presume to speak

for these performers: since we have no written record of the thoughts of

these particular performers, and many other indigenous peoples who were

made the object of written and filmic forms of ethnography, I will agree

with Gayatri Chakravortry Spivak that ultimately as a discursive figure

“the subaltern does not speak.” Yet I find the focus on the white anthro-

pologist, writer, or artist in critical works about Primitivism or Savagism

quite disturbing, because indigenous people are still reified as specimens,

metonyms for an entire culture, race, or monolithic condition known as

“Primitiveness.” The problem is compounded by what I describe as

“fascinating cannibalism” (to paraphrase Susan Sontag’s term “fascinat-

ing fascism”), the obsessive consumption of images of a racialized other

known as the Primitive.

4. I will refer to the chronophotography of Regnault as “film,” even though

they were not meant to be projected: they are literally strips of sequential

photographs. For more on film and physiology, see Lisa Cartwright,

“‘Experiments of Destruction’: Cinematic Inscriptions of Physiology,”

Representations 40 (Fall 1992).

5. See especially Emilie de Brigard, “The History of Ethnographic Film,”

Principles of Visual Anthropology, ed. Paul Hockings (The Hague and

Paris: Mouton Publishers, 1975) 1344; Martin Taureg, “The Develop-

ment of Standards for Scientific Films in German Ethnography,” Studies

in Visual Communication 9 (Winter 1983): 19-29; and Jean Rouch, “Le

Film Ethnographique,” Ethnologie Ge‘ne‘rale, ed. Jean Pokier,

Encyclope‘die de la Pleiade, (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1968) 24: 429-

471.

6. Let me be clear that when I refer to the “ethnographic” in cinema, I do

not mean to implicate all of what others call ethnographic film. Faye

Ginsburg writes that ethnographic film is ideally film that is “intended to

communicate something about that social or collective identity we call

‘culture,’ in order to mediate (one hopes) across gaps of space, time,

knowledge and prejudice.” She argues that media like film and television

made by indigenous peoples, such as the work of the Inuit Broadcasting

Corporation, is a necessary outcome of the “participatory cinema” pro-

duced by ethnographic filmmakers like Jean Rouch beginning in the

1970s. See Faye Ginsburg, “Indigenous Media: Faustian Contract or

Global Village?” Cultural Anthropology 6.1 (February 1991):104. A few

ethnographic filmmakers like Jean Rouch and David and Judith

MacDougall have made increasingly reflexive and collaborative cinema

in an effort to get beyond scientific voyeurism. I am not concerned here

with how best to envision an ideal of ethnographic cinema of the kind

that Rouch and others are pursuing. Instead, I seek to explain what I see

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

as the pervasive “racialization” of indigenous peoples in both popular 285

and scientific cinema. The films I am referring to in some way situate their

subjects in a former era; to see these films is to see a nexus between race

and the past.

7. Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its

Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983).

8. I drew my information on the history of French anthropology mainly from

the following sources: Elizabeth A. Williams, The Science of Man: An-

thropological Thought and lnstitutions in Nineteenth-Century France

(Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1983);Joy Dorothy Harvey, Races Spec-

ified, Evolution Transformed: The Social Context of Scientific Debates

Originating in the Socie‘te‘ d’Anthropologie de Paris 1859-1 902 (Ph.D.

diss., Harvard University, 1983); Donald Bender, “The Development of

French Anthropology,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Science

1 (April 1965): 139-151; and Histoires de l’anthropologie XVle-XlXe

sikcles, ed. Britta Rupp-Eisenreich (Paris: Klincksieck, 1984).

9. Indeed the concept of “nation” became popular at around the same time

as the concepts “race” and “volk,” and these terms in the beginning of

the century were fluidly intertwined: “race” was first used in the late

eighteenth century in natural history but was often used interchangeably

with “nation” and “people.” George W. Stocking, Jr., “Polygenist

Thought in Post-Darwinian French Anthropology,” in Race, Culture and

Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology (New York: Free Press,

1968) 42-68.

10. George W. Stocking, Jr. “Bones, Bodies, Behavior,” Bones, Bodies, Be-

havior: Essays on Biological Anthropology in History of Anthropology

(Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1988) 7-8. See also Adam

Kuper, The lnvention of Primitive Society: Transformationsof an Illusion

(London and New York: Routledge, 1988).

11. Harvey 133-138.

12. Paul Broca, Me‘moires de la Socie‘te‘ d’Anthropologie de Paris I1 (1865):

69-204 (quoted and trans. in Harvey 128).

13. For more on pathology see Georges Canguilhem, The Normal and the

Pathological, trans. Carolyn R. Fawcett (New York: Zone Books, 1991).

14. Filix Regnault, Des alte‘rations craniennes dans le rachitisme (Paris: G.

Steinheil, 1888) 12.

15. Lajard and Regnault, “La Venus accroupie dans Part grec,” La Nature

23 (29 June 1895):69-70. Regnault’s interest in the body and movement

preceded that of later anthropologists like Marcel Mauss and Franz Boas.

Mauss wrote that the body was the first instrument of man in “Les

Techniques du corps,” Sociologie et anthropologie (Paris: Presses Uni-

versitaires de France, 1950) 362-386.

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

286 16. “Des attitudes du repos dans les races humaines,” Revue Encycfope‘dique

(1896):9.

17. FClix Regnault, “Classifications des sciences anthropologiques,” Revue

anthropofogique (1931): 122. See for example, “Les attitudes de repos

dans Part sino-Japonais,” La Nature 23 (15 July 1895): 105-106;

“Prisentation d’une hotte primitive,” Buffetins de fa Socikte‘

d’anthropofogie de Paris 3 (21 July 1892): 4 7 1 4 7 9 ; and “Statuettes

Ethnographiques,” La Nature 22 (2 June 1894): 49-50.

18. Regnault wrote extensively on “primitive art,” a subject I deal with in my

dissertation. For Regnault on race see, for example “Pourquoi les nZgres

sont-ils noirs? (Etudes sur les causes de la coloration de la peau),” La

Me‘decine Moderne (2 October 1895): 606-607. In later years, however,

Regnault refined his notion of race, developing the idea of ethnie or

language and cultural group as an important index along with race, a

belief which put him at odds with Georges Montandon, a well-known

antisemitic anthropologist and supporter of the Vichy regime in the late

1930s. As early as 1902 he defined ethnie as “une union psychique a

opposer a la resemblance anatomique donnie par le mot race.” “Discus-

sion,” Buffetinsde fa Socie‘te‘de I’Anthropofogie de Paris 3 (3 July 1902):

680-68 1. Also see Jean-Loup Amselle, “Ethnie,” Encycfopoedia Uni-

versafis 8 (Paris: Encyclopoedia Universalis France S.A., 1990): 1971.

19. L. J. B. BCrenger-FCraud, Peuplades 2 4 , quoted in William B. Cohen,

The French Encounter with Africans: White Responses to Blacks, 1530-

1 880 (Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1980) 24 1;

and FClix Regnault, “De la fonction prihensile du pied,” La Nature ( 9

September 1893): 229-231. That the ethnographic body was linked to

other marginal elements in society such as criminals may be seen in the

fact that Regnault’s findings were used by the laboratory of the criminal

anthropologist Cesare Lombroso. See “Le pied prihensile chez les aliinis

et les criminels,” La Nature 1065 (28 October 1893): 339.

20. Charles Letourneau, Sociofogie d’apris f’Ethnographie (Paris: Reinwald,

1880) 4, quoted and translated in Harvey 139.

2 1. FClix Regnault, “Exposition Ethnographique de I’Afrique Occidentale au

Champ-de-Mars a Paris: SCnCgal et Soudan Franqais,” La Nature 23 (17

August 1895): 186.

22. “Un Village ntgre au Champ de Mars,” L’llfustration 2729 (15 June

1895): 508.

23. PetitJournafJune 5, July 14, July 26, August 15, 1895, quoted in William

H. Schneider, An Empire For the Masses: The French Popular Image of

Africa, 1870-1 900 (Westport and London: Greenwood Press, 1982) 169.

24. Paul Greenhalgh, Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universeffes,Great

Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851-1 939 (Manchester, U.K.: Manches-

ter University Press, 1988) 89; and Paul Greenhalgh, “Education, Enter-

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

tainment and Politics: Lessons from the Great International Exhibitions,” 287

The New Museology, ed. Peter Vergo (London: Redaktion Books, 1989)

74-98.

25. Cohen 281.

26. The story of the display of indigenous ethnic peoples is incomplete: there

is little written record of the thoughts of the performers, and little record

concerning the biography and aspirations of the promoters of the show.

There are however the accounts of the mass illustrated press, which shed

some light on the general public response to the exhibitions, and the

accounts by scientists such as those of FClix-Louis Regnault.

27. Williams 139.

28. Patricia Mainardi, Art and Politics of the Second Empire: The Universal

Expositions of 1855 and 1867 (New Haven and London: Yale University

Press, 1987) 169.

29. See Adolf Loos, “Ornament as Crime,” The Architecture of Adolf Loos,

eds. Yehuda Safran and Wilfried Wang (London: Arts Council of Great

Britain and the Authors, 1908). On the detail see Naomi Schor, Reading

in Detail: Aesthetics and the Feminine (New York and London: Methuen,

1987). On the detail and historical film see Phil Rosen, “From Document

to Diegesis: Historical Detail and Film Spectacle,” in the forthcoming Past,

Present: Theory, Cinema, History.

30. Religion could be explained in medical and scientific terms. Regnault

suggested, for example, that Jesus was a hysteric. See Hypnotisme, Reli-

gion (Paris: Schleicher Frkres, Editeurs, 1897).

3 1. Regnault, “Exposition Ethnographique” 184.

32. Regnault, “Les DahomCens” 372.

33. Ella Shohat gives a survey of cinema, gender, and colonialism in “Imaging

Terra Incognita: The Disciplinary Gaze of Empire,” Public Culture vol.

3 (1991 Spring): 41-70.

34. “Un Village nttgre” 508.

35. Regnault, “Les DahomCens” 372.

36. The throwing of money by visitors to performers in native villages was a

popular activity. If one imagines a day at the 1895 ethnographic exhibition

one immediately adopts the viewpoint of a French or an African: the fair

addressed viewers as national and racial subjects. But what about those

visitors of mixed heritage who came to the fair, or those performers who

stayed on after the expositions and settled down in Europe or North

America? One wonders about the visitors who were the children of French

colonialist fathers and West African mothers, and who had been sent to

be educated in France. I have no records of their observations, but one

might suppose that if asked to choose, they would have identified with

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

288 the French and the Eiffel Tower technology. It is a sad fact that the

exhibitions were so demeaning to Africans that a person of mixed blood

would have had little choice but to identify himself or herself as a French

subject.

37. Frantz Fanon explained the representation of people of African descent

by white society in these terms. See Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White

Masks: The Experiences of a Black Man in a White World, trans. Charles

Lam Markmann (New York: Grove Press, 1967) 163-165.

38. Many of the themes of the fair transferred to film: for example, one finds

several early films showing young nonEuropean children in harbors diving

for money. In addition, films of the world’s fairs were made by practically

all the major commercial film companies like Edison and Pathi.

39. Felix Regnault, “L’Histoire du cinkma, son r61e en anthropologie,” Bul-

letins et me‘moires de la Socie‘te‘d’Anthropologie de Paris 3 (6 July 1922):

65.

40. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Rich-

ard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981) 80.

41. Regnault, “L’Histoire du cinema” 64.

42. Regnault, “L’Histoire du cinema” 64.

43. Lajard, and Felix Regnault, “Poterie crue et origine du tour,” Bulletins

de la Socie‘te‘d’anthropologie de Paris 6 (19 December 1895): 734-739.

44. Felix Regnault, “Le langage par gestes,” La Nature 1324 (15 October

1898): 315-317.

45. Felix Regnault, “Des diverses mkthodes de marche et de course,”

L’Illustration (22 February 1896): 155.

46. Thus Regnault’s films must also be considered a form of applied anthro-

pology: one of his principal reasons for filming West Africans and French

soldiers was to prove his theories on how to best ameliorate the French

military walk. One of the main impetuses behind the promotion of this

walk seems to have been the Franco-Prussian War. Regnault claimed that

the German goosestep turned soldiers into automatons because i t was too

fatiguing: the marche en flexion was less tiring, and hence allowed the

soldier to think clearly. See Regnault, “Des diverses methodes de marche

et de course” 155; Regnault and De Raoul, Comment on marche;

Regnault, “La locomotion chez I’homme (Travail de 1’Institut Marey)”

Journal de physiologie et de pathologie ge‘ne‘rale15 (January 19 13):46-6 1.

The CinCmathGque FranCaise has films from the Marey Institute of De

Raoul as well as of other soldiers performing the marche en flexion which

must be classified as the work of Regnault. The titles for the films were

reportedly given by Lucien Bull, Marey’s assistant and director of the

Institut Marey. It is my contention that the above films as well as all of

the H n (Homme negre) series were by Regnault with the help of Charles

Published by Duke University Press

Camera Obscura

Comte and Commandant de Raoul. Other films by Regnault are in the 289

Collection Jean ViviC at the Archives du Film.

47. This example is “Run with Large Steps” (1895), cat. no. Hn 22

(CinCmath2que Franqaise). It is not reproduced here.

48. These examples belong to the collection of Jean Vivii and are housed at

the Archives du Film, cat. nos. 193 and 197. They are not reproduced

here.

49. “Les MusCes des films,” Biologica 2 (1912): XX; and “Un Musie de

films,” Bulletins et rne‘rnoires de la Socie‘te‘d’anthropologie de Paris 6 (7

March 1912): 95.

50. See Lion Azoulay, “L’Ere nouvelle des sons et des bruits. Musies et

archives phonographiques,” Bulletins de la Socie‘te‘ d’anthropologie de

Paris 1 (3 May 1900): 172-178; and “Liste des phonogrammes compos-

ant le musCe phonographique de la sociiti d’anthropologie de Paris,”

Bulletins de la Socie‘te‘d’anthropologie de Paris 3 (3July 1902): 652-656.

51. As quoted from Lorna Simpson’s Easy For Who To Say (1989),a won-

derful counterpoint to Regnault’s writing of race.

Published by Duke University Press

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Acting and Performance in Moving Image Culture: Bodies, Screens, Renderings. With a Foreword by Lesley SternD'EverandActing and Performance in Moving Image Culture: Bodies, Screens, Renderings. With a Foreword by Lesley SternPas encore d'évaluation

- Taking Stakes in the Unknown: Tracing Post-Black ArtD'EverandTaking Stakes in the Unknown: Tracing Post-Black ArtPas encore d'évaluation

- Bauhaus ConstructDocument12 pagesBauhaus ConstructKat Pse0% (1)

- Bhabha Transmision Barbarica de La Cultura MemoriaDocument14 pagesBhabha Transmision Barbarica de La Cultura Memoriainsular8177Pas encore d'évaluation

- Leviathan and The Digital Future of Observational DocumentaryDocument8 pagesLeviathan and The Digital Future of Observational DocumentaryjosepalaciosdelPas encore d'évaluation

- Citizen Kane - Orson Welles ScriptDocument22 pagesCitizen Kane - Orson Welles ScriptHrishikesh KhamitkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Silvia Federici - Precarious LaborDocument8 pagesSilvia Federici - Precarious Labortamaradjordjevic01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Doing Things Emotion Affect and MaterialityDocument12 pagesDoing Things Emotion Affect and MaterialityBetina KeizmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ethnographers Magic As Sympathetic M PDFDocument15 pagesThe Ethnographers Magic As Sympathetic M PDFPedro FortesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Culture of Nature 2014 SyllabusDocument18 pagesThe Culture of Nature 2014 Syllabusaivakhiv100% (1)

- Theory ReadingsDocument6 pagesTheory Readingsoh_mary_kPas encore d'évaluation

- Bazin, A. - Death Every AfternoonDocument6 pagesBazin, A. - Death Every AfternoonMaringuiPas encore d'évaluation

- Rob Shields - Spatial Questions - Cultural Topologies and Social Spatialisation-SAGE Publications LTD (2013)Document217 pagesRob Shields - Spatial Questions - Cultural Topologies and Social Spatialisation-SAGE Publications LTD (2013)merveozgurPas encore d'évaluation

- Towards A Critical Theory of Third World FilmsDocument18 pagesTowards A Critical Theory of Third World FilmsXavi Nueno GuitartPas encore d'évaluation

- Unbinding Vision - Jonathan CraryDocument25 pagesUnbinding Vision - Jonathan Crarybuddyguy07Pas encore d'évaluation

- Technoculture From Alphabet To CybersexDocument288 pagesTechnoculture From Alphabet To CybersexmarnekibPas encore d'évaluation

- Jonathan Crary Eclipse of The SpectacleDocument10 pagesJonathan Crary Eclipse of The SpectacleinsulsusPas encore d'évaluation

- Iyko Day - Being or NothingnessDocument21 pagesIyko Day - Being or NothingnessKat BrilliantesPas encore d'évaluation

- East Coast Greenway Guide CT RIDocument100 pagesEast Coast Greenway Guide CT RINHUDLPas encore d'évaluation

- J. P. Telotte - Science Fiction Film-The Critical ContextDocument28 pagesJ. P. Telotte - Science Fiction Film-The Critical ContextMJBlankenshipPas encore d'évaluation

- Landow - The Rhetoric of HypermediaDocument26 pagesLandow - The Rhetoric of HypermediaMario RossiPas encore d'évaluation

- Hall S - Europe's Other SelfDocument2 pagesHall S - Europe's Other SelfJacky ChanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hospitality of the Matrix: Philosophy, Biomedicine, and CultureD'EverandHospitality of the Matrix: Philosophy, Biomedicine, and CulturePas encore d'évaluation

- Bellour-The Unattainable Text-Screen 1975Document10 pagesBellour-The Unattainable Text-Screen 1975absentkernelPas encore d'évaluation

- Werbner, The Limits of Cultural HybridityDocument21 pagesWerbner, The Limits of Cultural HybridityNorma LoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Jeremy Patterson, "The History of Trauma and The Trauma of History in M. NourbeSe Philip's Zong! and Natasha Tretheway's Native Guard."Document22 pagesJeremy Patterson, "The History of Trauma and The Trauma of History in M. NourbeSe Philip's Zong! and Natasha Tretheway's Native Guard."PACPas encore d'évaluation

- Everyday Life and Cultural Theory An Introduction PDFDocument2 pagesEveryday Life and Cultural Theory An Introduction PDFChristina0% (1)

- The Curator As Artist SyllabusDocument7 pagesThe Curator As Artist SyllabusCristine CarvalhoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ortega Exiled Space In-Between SpaceDocument18 pagesOrtega Exiled Space In-Between Spacevoicu_manPas encore d'évaluation

- Shakespeare Valued: Education Policy and Pedagogy 1989-2009D'EverandShakespeare Valued: Education Policy and Pedagogy 1989-2009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Stucki, Andreas - Violence and Gender in Africa's Iberian Colonies - Feminizing The Portuguese and Spanish Empire, 1950s-1970s (2019)Document371 pagesStucki, Andreas - Violence and Gender in Africa's Iberian Colonies - Feminizing The Portuguese and Spanish Empire, 1950s-1970s (2019)Pedro Soares100% (1)

- Queer 14 FinalDocument9 pagesQueer 14 FinalJefferson VirgílioPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Visual Culture: Translating The Essay Into Film and Installation Nora M. AlterDocument14 pagesJournal of Visual Culture: Translating The Essay Into Film and Installation Nora M. AlterLais Queiroz100% (1)

- Heffernan, Staging Absorption and Transmuting The Everyday A Response To Michael Fried 08Document17 pagesHeffernan, Staging Absorption and Transmuting The Everyday A Response To Michael Fried 08lily briscoePas encore d'évaluation

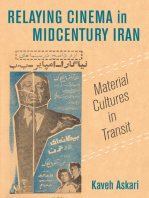

- Relaying Cinema in Midcentury Iran: Material Cultures in TransitD'EverandRelaying Cinema in Midcentury Iran: Material Cultures in TransitPas encore d'évaluation

- After Writing Culture. An Interview With George MarcusDocument19 pagesAfter Writing Culture. An Interview With George MarcusAndrea De AntoniPas encore d'évaluation

- eeman-Elizabeth-Time-Binds-Queer-Temporalities-Queer-Histories 1Document256 pageseeman-Elizabeth-Time-Binds-Queer-Temporalities-Queer-Histories 1Maria FerPas encore d'évaluation

- Stoler Colonial Syllabus Fall 10Document10 pagesStoler Colonial Syllabus Fall 10kartikeya.saboo854Pas encore d'évaluation

- Black Atlantic, Queer AtlanticDocument26 pagesBlack Atlantic, Queer AtlanticJohnBoalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Lusi PDFDocument19 pagesLusi PDFجو ترزيتشPas encore d'évaluation

- Brandon Labelle Interview by Anna RaimondoDocument32 pagesBrandon Labelle Interview by Anna RaimondomykhosPas encore d'évaluation

- Media Technology and Literature in The Nineteenth Century IntroductionDocument19 pagesMedia Technology and Literature in The Nineteenth Century IntroductionKumquatDemesmin-MgoyéPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Modernity Multiple - Multiple Modernities - Department of Art History and Archaeology - Columbia UniversityDocument3 pagesIs Modernity Multiple - Multiple Modernities - Department of Art History and Archaeology - Columbia UniversityohbeullaPas encore d'évaluation

- Flanagan Critical Play IntroDocument17 pagesFlanagan Critical Play IntroFelanPas encore d'évaluation

- Balazs Acoustic World PDFDocument6 pagesBalazs Acoustic World PDFBruna SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Aparicio Cultural StudiesDocument23 pagesAparicio Cultural StudiesKapu Tejiendo VidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Resurrecting the Black Body: Race and the Digital AfterlifeD'EverandResurrecting the Black Body: Race and the Digital AfterlifePas encore d'évaluation

- Mapping Visual DiscoursesDocument55 pagesMapping Visual DiscoursesVanessa MillarPas encore d'évaluation

- Trinh T. Minh-Ha Night PassageDocument1 pageTrinh T. Minh-Ha Night PassagegasparinflorPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond BeliefDocument68 pagesBeyond BeliefIndexOnCensorshipPas encore d'évaluation

- Spivak (2004) - Righting WrongsDocument59 pagesSpivak (2004) - Righting WrongsMartha SchwendenerPas encore d'évaluation

- De Loughrey Revisiting Tidalectics 2018Document6 pagesDe Loughrey Revisiting Tidalectics 2018lonenerryPas encore d'évaluation

- History TV and Popular MemoryDocument16 pagesHistory TV and Popular MemoryfcassinsPas encore d'évaluation

- Speculative Realism PathfinderDocument7 pagesSpeculative Realism PathfindersubmoviePas encore d'évaluation

- Katherine Mckittrick Sylvia Wynter On Being Human As Praxis 09 24Document16 pagesKatherine Mckittrick Sylvia Wynter On Being Human As Praxis 09 24Eva PosasPas encore d'évaluation

- Race Time and Revision of Modernity - Homi BhabhaDocument6 pagesRace Time and Revision of Modernity - Homi BhabhaMelissa CammilleriPas encore d'évaluation

- Esche Charles Bradley Will Art and Social Change A Critical Reader PDFDocument480 pagesEsche Charles Bradley Will Art and Social Change A Critical Reader PDFMihail EryvanPas encore d'évaluation

- (New Directions in Cultural Policy Research) Bjarki Valtysson - Digital Cultural Politics - From Policy To Practice-Palgrave Macmillan (2020)Document229 pages(New Directions in Cultural Policy Research) Bjarki Valtysson - Digital Cultural Politics - From Policy To Practice-Palgrave Macmillan (2020)Sebastian100% (1)

- On ANT and Relational Materialisms: Alan P. RudyDocument13 pagesOn ANT and Relational Materialisms: Alan P. RudyMariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Edouard Glissant, Poetics of RelationDocument11 pagesEdouard Glissant, Poetics of RelationAli AydinPas encore d'évaluation

- Memory Bites PDFDocument353 pagesMemory Bites PDFAli Aydin100% (1)

- Musser, Charles, at The BeginningDocument17 pagesMusser, Charles, at The BeginningAli Aydin100% (1)

- Crary, Jonathan - Techniques of The Observer PDFDocument34 pagesCrary, Jonathan - Techniques of The Observer PDFAli AydinPas encore d'évaluation

- Didi-Huberman, Georges - "Montage-Image or Lie-Image'", From 'Images in Spite of All'Document16 pagesDidi-Huberman, Georges - "Montage-Image or Lie-Image'", From 'Images in Spite of All'Ali AydinPas encore d'évaluation

- Hibike Euphonium - Crescent Moon DanceDocument22 pagesHibike Euphonium - Crescent Moon Dancelezhi zhangPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrep 1st PerioDocument5 pagesEntrep 1st PerioMargarette FajardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Suite 1 For Cello Solo For BB (Bass) Clarinet: Johann Sebastian Bach BWV 1007 PréludeDocument7 pagesSuite 1 For Cello Solo For BB (Bass) Clarinet: Johann Sebastian Bach BWV 1007 Préludewolfgangerl2100% (1)