Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Matthew R. Goodrum - Questioning Thunderstones and Arrowheads The Problem of Recognizing and Interpreting (Early Science and Medicine, 13, 5, 2008) PDF

Transféré par

carlos murciaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Matthew R. Goodrum - Questioning Thunderstones and Arrowheads The Problem of Recognizing and Interpreting (Early Science and Medicine, 13, 5, 2008) PDF

Transféré par

carlos murciaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Questioning Thunderstones and Arrowheads: The Problem of Recognizing and Interpreting

Stone Artifacts in the Seventeenth Century

Author(s): Matthew R. Goodrum

Source: Early Science and Medicine, Vol. 13, No. 5 (2008), pp. 482-508

Published by: BRILL

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20617752 .

Accessed: 08/06/2014 19:56

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

BRILL is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Early Science and Medicine.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early

'Science and

6 S" / ' 3Medicine

BRI L L EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 www.brill.nllesm

QuestioningThunderstones andArrowheads:

The ProblemofRecognizingand Interpreting

Stone

Artifactsin theSeventeenth

Century

Matthew R. Goodrum

VirginiaTech,Blacksburg*

Abstract

Flint arrowheads,spearheads,and axe headsmade by prehistoricEuropeans were gen

erallyconsidered before theeighteenthcentury to be a naturallyproduced stone that

formed in stormclouds and fellwith lightning.'Thesestoneswere called ceraunia,or

thunderstones,and itwas not until the sixteenthcentury that theirstatus as a natural

phenomenon was challenged.During the seventeenthcenturynatural historiansand

antiquaries began to suggest that thesecerauniawere not thunderstonesbut ancient

human artifacts.I argue thatnatural historymuseums, European contactwith the

stone-toolusing peoples in theNew World, and theclose relationshipbetween natural

history and antiquarianismwere critical to this reinterpretationof ceraunia. Once

theseobjectswere recognized to be ancient artifactstheycould be used to investigate

theearliestperiods of human historyfromsourcesother than texts.

Keywords

ceraunia, thunderstones,antiquarianism, prehistory,historyof archaeology,prehis

toricartifacts

During a violent thunderstormover theGerman townof Torgau in

May 1561 an object reportedlyfell from the sky accompanied by

a flashof lightning.'Theobject,which was later recoveredfrom the

place where it had apparently struck the ground, was a very hard

*

Department of Science and Technology in Society,Virginia Tech, Blacksburg,

VA 24061. Email: mgoodrum@vt.edu. I would like to thank the refereesfor their

comments and suggestions.

? Koninklijke BrillNV, Leiden, 2008 DOI: 10.1 163/157338208X345759

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 483

black stone shaped somewhat like an axe head or a wedge. Several

people witnessed this event and JohannesKentmann, a physician

and geological collectorwho lived in Torgau, later recorded the

occurrence.Therewas littledoubt about what thisobject was, many

had been collected and described by natural philosophers over the

centuries.Theywere called ceraunia inLatin,' a termmeaning thun

derbolt,but in thevarious vernacular languagesof Europe theywere

often called thunderstones(Donnerstein in German, pierre de fou

dre in French). There were plenty of previous instancesof ceraunia

being retrievedfrom the ground where lightninghad struck. In

1565 theSwiss naturalistKonrad Gesner described thediscoveryof

the ceraunia at Torgau and noted thatceraunia had also been found

aftera thunderstorminVienna some years earlier,while a similar

stone thathad fallenduring a storm in 1492.2

For compilers of medieval and Renaissance lapidaries,meteoro

logical treatises,and works on natural philosophy ceraunia were a

reasonablywell-understood part of the naturalworld. Natural his

torianscollected them as natural curiositieswhile peasants also fre

quently kept them as amulets to protect them from lightningor

fearedthem as elf arrows.3By the late seventeenthcentury,however,

a number of prominent naturalistsand antiquarieswere ridiculing

the centuries old idea that ceraunia were a natural phenomenon

associatedwith lightningand were arguing instead that theywere

stone implementsmanufactured by peoples in ancient times.This

paper is an inquiry into the reasons and themeans bywhich nat

ural philosophers during the seventeenthcenturycame to exchange

one understanding of what ceraunia were for a quite different

one.

Historians of archaeology have long been interestedin seeking

the firstindividualswho recognized flint tools as ancient artifacts,

1} The a bolt of

Latin ceraunia derives from the Greek work K?p0tt)vos, meaning light

ning.

2) rerum

Konrad Gesner, De et gemmarum maxime & simi

fossilium, lapidum figuris

litudinibusliber (Zurich, 1565), 64r-66v.

3) The

folklore ceraunia in has been

surrounding Europe explored by Christian Blin

kenberg, The ThunderweaponinReligion and Folklore,A Study inComparativeArchae

ology (Cambridge, 1911).

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

484 M.R. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

and they frequently mention that prior to the eighteenthcentury

these objects were considered to be thunderstones.iGlyn Daniel

has written about some of the importantfiguresin seventeenth-cen

tury archaeology who realized that ceraunia were actually stone

implements.More recentlyAlain Schnapp has examined the prob

lem of how antiquaries during the seventeenthand eighteenthcen

turiescame to recognizeprehistoricstone tools as such.5Daniel and

Schnapp treatthisproblem only briefly within the contextofmuch

broader discussions of thehistoryof prehistoricarchaeology.Stuart

Piggott has provided a somewhatmore nuanced investigationof the

subject inAncientBritonsand theAntiquarian Imaginationwhere he

situates this specificproblem within the context of European sci

ence, philosophy,and religion.Piggott shows that in order to under

stand seventeenth-century archaeological researchone must recognize

the role that the biblical historyof mankind, the discoveryof the

New World, and the relianceon classicalGreek and Roman descrip

tions of the ancient Gauls, Britons, and Germans had on scholars

interpretingancient antiquities.6

Despite the importannceof thesecontributions, theyhave some

shortcomings.They view theproblem of the recognitionof "prehis

toric stone tools" solely from the perspective of the history of

archaeology.The story for them essentiallybegins in the late sev

enteenth century,when this interpretationalswitch occurs.While

4) Some are Marcel Baudouin and Lionel "Les

prominent examples Bonnem?re,

haches polies dans l'histoirejusqu'au XIX si?cle,"Bulletin de la Soci?t?d'Anthropologie

(1904), 496-547; Ernest-Th?odore "Mat?riaux pour servir ? l'histoire de l'ar

Hamy,

ch?ologie pr?historique,"Revue arch?ologique,fourth series,4 (1906), 239-259; and

Annette de en France: des super

Laming-Emperaire, Origines l'arch?ologie pr?historique

sitionsmedievales? la d?couvertede l'homme fossile (Paris, 1964).

5)

Glyn Daniel, The Idea ofPrehistory(Baltimore, 1964) and^4 ShortHistory ofArchae

ology (London, 1981); Alain Schnapp, La Conqu?te dupasse. Aux originesde l'arch?o

logie (Paris, 1993). Schnapp's book has been translatedintoEnglish by IanKinnes and

Gilliam Varndell as TheDiscovery ofthePast (NewYork, 1997).

6) Stuart Ancient Britons and the Antiquarian Ideas from the

Piggott, Imagination:

Renaissance to the (London, 1989). has also examined developments

Regency Piggott

in seventeenth and in Ruins in a Landscape: Essays

in

eighteenth-century archaeology

1976). Thomas Kendrick has drawn attention

Antiquarianism (Edinburgh, Downing

to some of these issues inBritishAntiquity (London, 1950).

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 485

theymention the previouslyheld opinion that these objects were

thunderstones,they do not examine the scientific tradition that

upheld thisopinion. I want to offera more complete and system

atic examinationof how the interpretation of ceraunia changed dur

ing the course of the seventeenthcentury.It is necessary to examine

this issue fromwithin thecontextof sixteenthand seventeenth-cen

turynaturalphilosophy in order to understand thegeological,mete

orological, and chemical theories thatwere invoked to explain the

existenceof thunderstones. Once one recognizes thatcerauniawere

not mysterious phenomena demanding explanation but a generally

familiarand understood natural curiosity,then the immediateques

tion thatneeds to be answered iswhat happened during the course

of the seventeenthcentury to make some investigatorsbegin to

doubt the traditionalexplanation of ceraunia and to suspect that

theyhad a quite differentorigin and meaning.

This is the basic problem to be explored here.When it is ap

proached from this perspective the seventeenth-century change in

interpretation becomes much more complex and interestingthan it

is presented inmany historiesof archaeology.The changing inter

pretation of ceraunia becomes intricatelylinked to other develop

ments thatwere taking place in natural history, specifically the

debate over another categoryof geologic specimens,namely fossils.

Justas natural historianswere considering the possibility that "fig

ured stones" that resembledplants or animalsmight in factbe the

petrifiedremainsof once livingorganisms,7some were also recon

sidering their interpretationof ceraunia for some of the same rea

sons.

The interpretationof ceraunia was also changing because new

groups of researcherswere studying them.Natural historianswere

collecting and examining them as thunderstones,but by the end of

7) nature over fossils and

The complexity and multifaceted of this debate their mean

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is in Martin

ing during expertly displayed

J. S. Rudwick, TheMeaning ofFossils:Episodes in theHistory ofPalaeontology,2nded.

(New York, 1976), chs.1-2; Paolo Rossi, TheDark Abyss ofTime: TheHistory ofthe

Nations fromHooke toVico, tr.Lydia G. Cochrane (Chicago,

Earth and theHistory of

1984), 1-10.

chapters

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

486 M. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

the seventeenthcentury antiquarieswere also beginning to collect

and study theseobjects.Antiquarianism was a discipline on the rise

during the sixteenthand seventeenthcenturies that combined the

activities of the historical document collector, archaeologist, and

genealogist.8Antiquaries brought a differentbody of knowledge and

differentprinciplesof interpretationto the study of ceraunia than

earliernaturalphilosophersdid. Historians such asDaniel, Schnapp,

and Piggott have argued that a critical element that enabled anti

quaries to recognize that ceraunia were in fact stone implements

was the discovery of stone tool using peoples in theNew World

and the addition of such artifactsto the natural historymuseums

of European collectors.9Yet these authors offervery few details

about justwhat informationwas available to European antiquaries

and natural historians about the stone implementsfrom theNew

World. We must not only examine thisquestion more thoroughly,

but we must also address the question of the criteria that natural

historians and antiquaries resorted to in order to distinguishprod

ucts of nature (such as fossils,minerals, or meteorites) from arti

factsof human production (such as flintarrowheads and polished

stone axes).Moreover, once antiquaries began to argue that cerau

nia were indeed ancient stone implements, theywere immediately

faced with yet another problem, that of explaining why some

ancient Europeans made tools from stone when metal toolswere

obviously superior and were used by many ancient peoples.

The recognition thatcerauniawere human artifactswas a pivotal

event in thehistoryof prehistoricarchaeology.It led antiquaries and

natural historians in theeighteenthcentury to reconsidertraditional

8) as a its connections to natural

On antiquarianism scholarly activity and history and

research the early modern see G.

archaeological during period Stanley Mendyk, 'Spec

ulum Britanniae: and Science in Britain to 1700

Regional Study, Antiquarianism,

(Toronto, 198 8); Rosemary Sweet, Antiquaries: The Discovery Past in

ofthe Eighteenth

CenturyBritain (NewYork, 2004); Michael Hunter, "TheRoyal Society and theOri

in

gins ofBritishArchaeology: I" Antiquity,45 (1971), 113-121 [reprinted Michael

Hunter, Science and the Shape Intellectual in Late Seventeenth

of Orthodoxy: Change

CenturyBritain (Woodbridge, 1995), 181-200].

9) A Ancient Britons and the Anti

Daniel, Short History ofArchaeology, 35; Piggott,

quarian Imagination, 73-86.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

M.R Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 487

notions of thehistoryof the firstEuropeans and generated entirely

new questions and methods of investigatingearly human history

through itsmaterial remains.10By examining the process bywhich

they revised their interpretationof ceraunia we learnmuch more

than just about the beginningsof one area of prehistoricarchaeol

ogy,we can learn something about the practice of science in the

seventeenthcentury and the close relationship that existed at that

time between the natural and the human sciences.

Ceraunia and EarlyModern Natural History

Natural historiansduring the sixteenthcenturyaccumulated a curi

ous and heterogeneous collection of factsabout ceraunia fromear

lier authors, popular folklore,and personal experience. Everyone

agreed theywere a distinctive type of stone found throughout

Europe, but descriptionsof thesestonesvaried.Konrad Gesner,who

was a diligent collector of obscure factsabout nature, asserted in

his De rerumfossiliumfiguris (1565) that ceraunia sometimes are

pyramidal in formbut others resemblewedges or hammers."1The

Italian natural philosopher Camillo Leonardi also mentions them

having a pyramidal shape in a book firstpublished in 1502,12 as

did the Italian lapidaryCleandro Arnobio a century later.13Georg

Bauer (Agricola), a German naturalistwho was widely recognized

as an authorityon geology, also refersto ceraunia, but described

themas being either round or oblong stones that resembledanother

10)

Matthew R. Goodrum, "The Meaning of'Ceraunia: Natural History,

Archaeology,

and the Interpretation of Prehistoric Stone Artifacts in the

Eighteenth Century," Brit

ishJournalfor the

History ofScience, 35 (2002), 255-269.

u) rerum

Gesner, De 63v.

fossilium,

12)Camillo

Leonardi, Speculum lapidum (Paris, 1610), 88.

13)

Oleandro Arnobio, II tesoro d?lie trattato intorno aile vertuti, e

gioie, maraviglioso

rare di tutte le avori, inicorni, bezaari, balsami, coceo,

propriet? pi? gioie, perle, gemme,

e malacca, e di tutte

l'altrepi?trepi? famose, epregiate da diligentissimi scrittori, antichi,

e moderni, arabi, greci, latini, editaliani, e lodate, stimate, e

sagri, mondaniplenamente

conosciute salutevoli, e medicinali: d?lie quali anche spesso

sene accenna nette divine carte,

& insime si discorre e valore dell'eccellentissimo letterario

delpregio, delgiacinto (Venice,

1602), 180-181.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

488 MR. GoodrumIEarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

typeof stone called brontia, except thatbrontia had lines or ridges

on their surfacewhile ceraunia are smooth.14To make matters

worse, Gesner noted thatmany people thought that glossopetrae,

yet another typeof stone thatwas generatingconsiderable debate,

were often confusedwith ceraunia or were considered to have some

kind of relationshipwith them.15

In the textsof sixteenth-centurynaturalists,then,ceraunia appear

as a heterogeneous category of stones of varying color that are

shaped like pyramids,wedges, hammers, spheres,or are sometimes

triangularwhen glossopetrae are included. This is one of the fac

tors that complicated the interpretationof ceraunia in the seven

teenthcentury.However, there is one featurethat all theseauthors

agreed upon. Indeed, itwas the feature thatmore than any other

defined them as a natural type.According toCamillo Leonardi and

Cleandro Arnobio, ceraunia fall from the clouds and impact the

ground where lightninghas struck."6FranciscusTittelmans agreed

that thesestoneswere thrownby lightningand were thereforecalled

"cuneus fulminis."'17 Agricola and Gesner took a somewhatmore

skeptical tone, stating that itwas commonly believed thatceraunia

fallwith lightning,but leaving the reader to choose whether this

popular beliefwas to be accepted or rejected."8

The possible meteorological origin of ceraunia continued to be a

subject of discussion into the seventeenthcentury.Various alche

mists and natural philosophers applied theirknowledge of nature

to explain how these stonesmight be produced. Libert Froidmont,

thewell-known Louvain theologianand natural philosopher,argued

14) Bauer De natura 262. Gesner also notes

Georg Agricola, fossilium (Basil, 1546),

the link between ceraunia and brontia, see De rerum 62r. The known

fossilium, objects

as brontia naturalists were later considered to be fossilized sea ur

by early modern

chins.

15) rerum

Gesner, De fossilium, 67r.

16) 7/ tesoro d?lie gioie, 181

Leonardi, Speculum lapidum, 88; Oleandro Arnobio,

182.

17) Franciscus naturalis philosophiae seu de consideratione

Tittelmans, Compendium

rerum naturalium ad suum creatorem reductione, libri XII (Lyon, 1545),

earumque

67.

18) De natura De rerum 62r.

fossilium, 262; Gesner, fossilium,

Agricola,

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 489

that ceraunia were produced when terrestrialexhalations rose into

the atmospherewhere theymixed with themoisture present in

clouds. The resultingmatter was then baked by the heat of light

ning into a very hard stone that fell to the earth.19But therewere

featuresof ceraunia thatwere difficultto explain by this theory.

Konrad Gesner noted thatone kind of ceraunia called a Straalham

mer, orfulmineummalleum inLatin, was shaped exactly likea wedge

and even possessed a hole throughone end asmetal axes do. Among

the factsthatGesner assembled about thesespecimenswas that they

were composed of a material that in all respects resembled flint,

because when it was struckwith iron it produced sparks.20The

hole thatpassed throughone end of the stonewas a particularpuz

zle toGesner, who was however able to devise a clever explanation

for it, suggestingthat thehole was produced not by art,but by the

stone'sviolentmotion through the air.2'

As successivegenerationsof natural philosophersexamined cerau

nia doubts about theirmeteorological origins grew, however. In

1609 the Flemish natural philosopherAnselm Boethius de Boodt

examined the question anew. De Boodt was physician toRudolph

II of Prague, and his interestin alchemy and rare stones led to his

appointment as Rudolph's Chief Lapidary. In his widely read Gem

marum et lapidum historia (1609), which was later published in

French as Le parfaict joaillier (1644), de Boodt discussed ceraunia

and the popular belief that theywere produced in clouds and fell

with lightning.Like Gesner, de Boodt took particularnote of their

form,stressingtheir resemblancewith wedges, axes, and hammers,

although theywere of heavy hard stone, not metal. De Boodt also

noted, as Gesner had done, thatceraunia have the same properties

as flint.Addressing the intriguinghole found in some ceraunia, de

Boodt obseved that theywere wider on one end thanon the other,

19)Libert

Meteorologicorum libri sex (Antwerp,1627), 56. This work was

Froidmont,

widely known and appeared in several editions the century, one

throughout including

published inLouvain in 1646 and one inLondon in 1670.

20) rerum

Gesner, De 62v.

fossilium,

21)

Ibid., 63v.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

490 MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

like those bored into metal hammers to receive a wooden han

dle.22

De Boodt thereforeproposed a quite novel idea. He suggested

that cerauniawere not produced in clouds by natural processes but

insteadwere iron tools thathad petrifiedover time.23 He also iden

tifiedsome problemswith the traditionalmeteorological explana

tionof theceraunia.Natural philosophers-physiciens, in theFrench

translation-had argued that ceraunia were produced by earthy

vapors mixing with moisture in clouds and then baked into hard

stones by theheat of lightning.But if thiswas themanner of their

formation,one would expect them to be spherical.Nor did this the

ory adequately explain the presence of the hole and its conical

shape.24 It did furthermorenot seem reasonable to de Boodt that

such a heavy stone could be formed in clouds and carried by the

wind overmountains during storms,as theywould have had to fall

to the ground before theywere fully formed.25The most reason

able explanation for theobserved featuresof ceraunia thereforehad

to be that theyhad originated as human artefacts,as weges and

hammers. But since such tools have always been made of iron or

some othermetal, theonlyway to account forceraunia is that these

metal toolswere turned to stone in the course of time.26

The impact of de Boodt's reinterpretation of ceraunia is evident

inUlisse Aldrovandi's discussion of ceraunia inMuseum metallicum

(1648).27 Aftermentioning that ceraunia derive their name from

the common belief that they fallwith lightning,Aldrovandi draws

the reader'sattention to their close resemblance to human tools.

22) Le o? sont

Anselm Boethius de Boodt, parfaict joaillier; ou, Histoire des pierreries:

descrites leur naissance, iusteprix, moyen de les cognoistre, &

se des con

amplement garder

tre-faites, facultez medecinales, & proprietez curieuses, tr. Jean Bachou (Lyon, 1644),

620.

23) Ibid.

24)

Ibid., 622.

25)

Ibid., 623.

26)

Ibid., 620.

27) Aldrovandi never this work and itwas more than forty

completed only published

after his death. Bartolomeo Ambrosini (1588-1657) edited Aldrovandi's notes

years

final text were

for the book, and portions ofthe composed by Ambrosini.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

M.R Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 491

Like de Boodt, he takesparticularnote of thehole thatmost exem

plars possess, and of the conic shape of the hole, as ifdrilled fora

handle. He also notes that ceraunia are like flintin that theypro

duce sparkswhen struckwith iron.28For these reasons,Aldrovandi

says, there are authorswho believe ceraunia to be petrifiedmetal

implements.But he acknowledged that not everyone agreedwith

thisnew hypothesis,offeringthegenerallyheldmeteorological expla

nation as an alternative.29 But perhaps themain obstacle to the

new theorywas the fact thatmany people claimed to have observed

ceraunia fallduring stormsor to have dug up ceraunia fromspots

struckby lightning.30 Thus, Aldrovandi remainedambivalent about

the origin of ceraunia, although many of the facts he presented

about them pointed to the features they sharedwith man-made

implements.But even Boethius de Boodt had recognized that the

idea thatcerauniawere "fleschedu foudre" (thunderarrows)was so

widely held that itwould appear to be madness to deny it, in par

ticularbecause of themany crediby eyewitnessreports.3'

The interpretation of cerauniawas also complicated by the con

fusionwhat objects actually belonged to that category.Aldrovandi

cited naturalistswho described ceraunia as coming in a diversevari

etyof forms,includingpyramids,wedges, hammers,axes, and discs.

Therewerealso authors

who included

glossopetrae

and belemnites

in thiscategory.32

Glossopetrae

werehardshinystones

whose tri

angular shape resembled iron arrowheadsor spearheads,while bel

emniteswere conical shaped stones, somewhat like the end of a

lance or javelin. Boethius de Boodt thought that belemniteswere

so similar in form to the ironpoints used to head arrows and jav

elins in ancient times thatone could easily conclude that theywere

just suchweapons turned to stone.33Natural historiansduring the

28)Ulisse

Aldrovandi,Museum metallicum in librosIII distributum(Bologna, 1648),

607.

29)

Ibid., 608.

30)

Ibid., 607-608.

31)De

Boodt, Le parfaictjoaillier, 620-621.

32)

Aldrovandi,Museum metallicum, 600, 609; de Boodt, Le parfaictjoaillier, 436,

620.

33)De

Boodt, Le parfaictjoaillier, 614-618.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

492 MR. Goodrum/]Early

ScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

seventeenthand eighteenthcenturygradually came to the conclu

sion that glossopetraewere fossilizedshark teethwhile belemnites

were the fossilizedshells of a typeof marine mollusk, but the fact

that glossopetrae, belemnites, brontia, and ceraunia were regarded

as relatedphenomena during the sixteenthand parts of the seven

teenthcentury indicates the complexityof the problem of explain

ing the origin and meaning of fossilsand other "figuredstones."

Aldrovandi tried to correct some of the confusion over belem

nites by pointing out thatmany people incorrectlyreferredto stone

weapons manufactured by theRomans as belemnites,whereas true

belemniteswere naturallyoccurringconical stones.34 Yet Aldrovandi

may have added to the confusion over what was a true ceraunia

when in one plate he depicted severalglossopetrae along with per

forated stone axes under the heading of ceraunia,while elsewhere

he illustratedseveral fossil shark's teethbut mistakenly included a

flintarrowhead thathe identifiedas a glossopetrae (see Figure 1).35

This confusion reflectsthe fact thatmost authors only included

wedge or hammer shaped stones as ceraunia,while stones shaped

like arrowheadswere treatedseparatelyor as glossopetrae.

We have seen thatGesner, de Boodt, and Aldrovandi all com

mented on the similarityof certain featuresof ceraunia to metal

tools, and that de Boodt went as far as to propose that ceraunia

were not thunderstonesbut were metal tools thathad been turned

to stone. The French natural philosopher Jean-Baptistedu Hamel,

secretaryof theAcademie Royale des Sciences and professorat the

College royale,adopted this explanation and argued in 1660 that

cerauniawere metal wedges, axes,hammers,and arrowheadschanged

to stone by a "lapidifying spirit."36Natural philosopher's ideas

about cerauniawere changing,but theconviction thatpeople would

34) Museum 618. On he provides an illustration of

Aldrovandi, Metallicum, page 634

what he calls a or artificial belemnite, which he says the Romans

"lapis Sagittarius"

used as arrowheads.

35)

Ibid., 611, 604-5.

36) De meteoris et libri duo: in priore libro mixta

Jean-Baptistedu Hamel, fossilibus

in sublimi a?re vel apparent fuse pertractantur: posterior

imperfecta qu que velgignuntur

liber mixta perfecta complectitur: ubi salium bituminum, et metal

lapidum, gemmarum

lorum nature causa et usus inquiruntur (Paris, 1660), 210.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

M.R Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 493

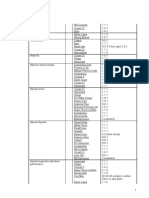

644. VIRUf~m~ikMS_ ~ k~iaiM Y LiUIY. 6os

& d

o~pe~ma~d~SNU ~ Q~P~*U~"map;P

Liz_~~~~~i

Figure 1. Plates fromUlisse Aldrovandi'sMusaeum metailicum (pp. 604-605) depict

ingvarious specimensof glossopetrae,or fossilizedshark'steeth.However, theobject

in theupper rightis in facta flintarrowheadand not a glossopetrae.Flint arrowheads

were frequentlyconfusedwith glossopetrae in the seventeenthcentury.

only make tools out of metal and not out of stone prevented them

fromdrawing the conclusion that some Europeans had once made

tools out of stone.Yet this ideawas not entirelyinconceivable since

at least one person had already reached this conclusion.

Michele Mercati and theOrigins of Ceraunia

Michele Mercati has long been touted by historiansof archaeology

as the first person to have recognized that the stone axes and arrow

were in fact

heads collected by natural historians as thunderstones

toolsmade by earlyEuropeans.3 But his contribution to the inter

37) Andr?

Vayson de Pradenne, "Les pr?curseurs de la pr?histoire," 31

L'anthropologie,

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

494 MR. Goodrum/Early ScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

pretation of stone artifactsduring the Renaissance is complicated

by the fact thathis ideaswere not published untilmore than a cen

turyafterhis death, although themanuscript where he discussed

thiswas accessible during the seventeenthcentury.Mercati studied

medicine and philosophy at theUniversity of Pisa and served as

superintendentof theVatican botanical garden under severalpopes

at the end of the sixteenth century.This position gave Mercati

access to theVatican's impressivenatural historymuseum, and very

importantlyto its largegeological collection,which containedmany

specimens of ceraunia. Like many natural historymuseums estab

lished during the earlymodern period, zoological, botanical, and

geological specimenswere ranged alongside archaeological artifacts

and ethnographicobjects fromAfrica,Asia, and theAmericas.38

Mercati was devoted to the study of minerals and fossils,and

before his death in 1593 he completed a massive geological treatise

titledMetallotheca.39His book contains a lengthyand highly orig

inal discussion of ceraunia. In chapter 15Mercati examines "cerau

nia cuneata," or ceraunia having the shape of a wedge or axe.After

mentioning thatpeople have traditionallythoughtthem to fallfrom

the skywith lightning,which iswhy they are called "folgara" in

Italy,he states that they exactly conform to the shape of an axe

(securis).40In the accompanying plate thatappears in the published

text six polished stone axes are depicted under the caption "lapis

fulmineusvulgo fulgur."In thenext chapterMercati discusseswhat

he refersto as "ceraunia vulgaris,et sicilex,"which consists primar

ilyof stone arrowheads.These objects, also called sagitta,were com

(1921), 357-360; Laming-Emperaire,Originesde l'arch?ologie en

pr?historique France,

44-48;

38) On museums of the sixteenth and seventeenth see Oliver

natural history century,

Museums: The Cabinet ofCurios

Impey andArthurMacGregor (eds.), TheOrigins of

ities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe (Oxford, 1985).

39)

For an extensive discussion of Mercati's geological

research and theMetallotheca

see Bruno Accordi, "Mich?leMercad (1541-1593) e laMetallotheca," Geol?gica Ro

mana, 19 (1980), 1-50.

40)Mich?le et

Mercati, Metallotheca. Opus posthumum, auctoritate, munificentia d?

mentis Undecimi Maximi e tenebris in lucem eductum, ed. Johannes Maria

Pontifias

Lancisi (Rome, 1717), 241.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 495

mon in Italy and have a triangularshape, like the heads of arrows

(telorum)made of metal, although theseobjects appear to be com

posed of flint.41

There are two opinions regardingthe origin and nature of these

objects, according toMercati. Many people believe theyare thrown

to theground by lightning,but thosewho know history think that

in early timesbefore ironwas used tomake weapons people made

blades and arrowheadsof hard flint.42 Mercati offeredevidence in

support of this idea. He cites referencesin the Bible that sharp

stone kniveswere used by theHebrews to performcircumcision as

well as Roman textsthatdescribe theuse of stone arrowheadsbefore

the use of iron.He also cites the Roman Epicurean philosopher

Lucretius,who in theDe rerumnature imagined primordialmen

using horn and sharpened stoneweapons before theybecame civi

lized and learnedmetallurgy. In addition,Mercati also reliedupon

ethnographic informationthat therewere people in theNew World

("orbisoccidui") who still used stone implements,because theydid

not know the use of metal.43 Indeed,many accounts had been pub

lished about the inhabitantsof theNew World and theirway of

life,mentioning thatmany groups did not possessmetal tools but

insteadused implementsmade of stone.Many such specimenswere

brought back to Europe and entered natural history collections,

including theVatican's large collection.Mercati seems to have rec

ognized the resemblancebetweenEuropean ceraunia andNew World

axes and arrowheadshoused in theVatican natural historymuseum

and combined thiswith his knowledge of classical sources to draw

the conclusion that cerauniawere in fact stone tools.

Mercati took his conclusions even further,though.He noticed

the rough chipped surface of these European arrowheads,which

indicated that theywere made by strikinga piece of flintwith

another stone. He even recognized the stump at the base of these

arrows as where the arrowwould be hafted to thewooden shaft.44

41>

Ibid., 243.

42>Ibid.

43)

Ibid., 243-244.

**>

Ibid., 244.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

496 MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

But all of this raised a very importantquestion: why would ancient

Europeans (orNew World peoples for thatmatter) use stone imple

ments when metal ones were superior and the biblical record tells

us thatmetallurgywas inventedby Tubal-Cain not long after the

creation of mankind? To thisMercati offersan ingenious answer.

He suggests that as a resultof the devastation caused by the bibli

cal deluge and the subsequentmigration of the sons of Noah and

theirdescendants into the harsh wildernesses of theworld, some

groups lost theknowledge ofmetallurgyeitherbecause theylost the

skills requiredor because they lived in regions that lacked iron. In

these cases, some nations would have resorted to the use of stone

implementsuntil theycould rediscovertheprinciplesofmetallurgy.45

So, for instance,Mercati suggests that in Italy,where cerauniawere

frequentlyfound in thecountryside,theaboriginal inhabitantsmust

have made spear points out of flintuntil the use of ironwas rein

troduced through tradewith other nations.46

Thus Mercati realized that accepting the idea that cerauniawere

not thunderstonesbut ancient stone implements had surprising

implicationsforour interpretation of earlyhuman history.Yet these

implications could be adequately addressed within the accepted

understandingof human history provided by theOld Testament.

Mercati felt reasonably assured that he had found the true origin

of ceraunia.He had been able to show how theymight have been

made out of pieces of flintand had even found classical sources that

supported the idea that stone tools had been used in the past. Yet

some doubt remained in his mind because therewas the possibil

ity thatcerauniamight simplybe "sportsof nature" (naturaejocus),

since itwas well-known and widely accepted thatnature possessed

the capacity to produce objects thatclosely imitatedart (just as nat

ural historians investigatingfossilswere also aware thatnature could

imitateorganic forms in inorganicmaterial). 4 Indeed, one criti

cism of the idea that some ceraunia were stone arrowheads, he

notes,was the fact thatmany were so small that one might think

45) Ibid.

46)

Ibid., 245.

47) Ibid.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 497

them useless as arrowheads.But the evidencemore heavily favored

an interpretation of ceraunia as human artifacts,andMercati mar

shaled some powerful arguments in support of this idea. Remark

ably,Mercati had reached this conclusion in the late sixteenth

century,even beforeBoethius de Boodt had published his own inno

vative interpretation.The problem was thatMercati's Metallotheca

was not published until 1717, and it appears that few if any sev

enteenth-century natural historiansor antiquarieswere aware of his

groundbreakingopinions, though some contemporariesmay have

read his work inmanuscript form.

Antiquarianism and Ancient Stone Artifacts

There were severalcritical elements thathelpedMercati to imagine

that cerauniamight be ancient stone implements that also played

a central role in the late seventeenthcenturywhen other natural

historiansand antiquaries began to reach the same conclusion inde

pendently.The formationof largenatural historycollections during

the sixteenthand seventeenthcenturiesmeant thatmany specimens

of ceraunia could be assembled and compared to one another, as

well as to other fossilsand minerals. This helped Gesner, de Boodt,

and Aldrovandi to begin the process of clarifying what the essen

tial characteristicsof ceraunia were and what distinguished these

objects fromother kinds of "figuredstones."The comparisonwith

stone tools broughtback fromtheNew World was also significantly

contributed to the reinterpretation of ceraunia, as we have seen in

Mercati's case.

Europeanexplorers

wereparticularly

struck

bywhat theyconsid

ered to be the crude and barbarous way of life of many of the

native peoples of theAmericas, and by the early seventeenthcen

tury bookshadbeenpublishedthatoffered

numerous vividdescrip

tionsof the physical attributesof theAmericans, theirculture and

way of life,and especially theirclothing,dwellings,domestic imple

ments and militaryweapons. Among theseaccountswere occasional

referencesto the use of stone tools by some New World peoples.

Jean de Lery wrote in 1578 that the natives of Brazil used sharp

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

498 M.R. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

stones as knives and Rene Goulaine de Laudonniere noted that the

Indians of Florida used arrows pointed with the teeth of fish or

workedstones.48

finely The Englishexplorer

JohnSmithobserved

that theSasquesahanock ofVirginia used bows and arrows in their

hunting and warfare, and that theirarrowswere made from sprigs

ofwood or reedsheaded with "splintersof a white cristall-likestone,

in formeof a heart, an inch broad, and an inch and a halfe or

more long."49In the place of metal swords theyused the horn of

a deer inserted into a piece of wood like a pickaxe and theymade

hatchets by forcinga long stone sharpened at both ends througha

wooden handle.50RogerWilliams noted that the Indians of New

England used a varietyof stone implements in the place of metal

knives, awls, hatchets, or hoes.51

These books not only described the tools and weapons used by

many New World peoples but theyalso contained remarkableillus

trations thatportrayed these people and theirpeculiar customs to

enthrallEuropean readers.52 But perhaps evenmore importantthan

the descriptions and images of stone implements from theNew

World were the largequantities of ethnographicobjects thatEuro

48) en la terre du Br?sil, autrement

Jean de L?ry, Histoire d'un voyage fait dite Am?rique

(La Rochelle, 1578), 244-245; Ren? Goulaine de Laudonni?re, L'Histoire notablede

la Floride situ?e es Lndes Occidentales, contenant les trois voyages faites en icelle

par

cer

tains & pilotes Fran?ois, descrits par le Capitaine Laudonni?re, a com

Capitaines qui y

mand? d'un an trois moys: ? a este adioust? in

l'espace laquelle quatriesme voyage fait par

leCapitaine Gourgues (Paris, 1586), 4r.

49) The Generall Historie and the Summer Isles:

John Smith, of Virginia, New-England,

with theNames and Governours from their First Beginning

ofthe Adventurers, Planters,

an: 1584 to thisPresent 1624 (London, 1624), 24-25, 31.

50)

Ibid., 31.

51)

RogerWilliams, A Key into theLanguage ofAmerica: Or, An Help to theLanguage

of Natives in thePart ofAmerica, CalledNew-England(London, 1643), 38, 148.

the

52)Fredi on theOld

Chiappelli, First Images ofAmerica: The Impact oftheNew World

(Berkeley,1976); Paul H. Hulton, "Images ofthe New World: le

Jacques Moyne de

and John White," in K. R. Andrews, N. P. Canny, and P. E. H. Hair, (eds.),

Morgues

TheWestwardEnterprise.EnglishActivities in Ireland, theAtlantic, and America 1480

1650 (Liverpool, 1978), 195-214; Paul H. Hulton, "Realism andTradition inEthno

in A. Ellenius, (ed.), The

logical

and Natural History Imagery ofthe 16th Century,"

Natural Sciences and theArts: Aspects of Interaction from the Renaissance to the Twentieth

Century (Stockholm, 1985), 18-31.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 499

pean explorersbrought back toEurope, which found theirway into

natural historycollections. By the seventeenthcentury itwas com

mon for the best natural history collections in Europe to possess

clothing,weapons, ornaments,and other culturalobjects fromNorth

and South America.53Among theseobjects were stone arrowheads,

polished stone axes, stone knives, and a varietyof otherweapons

or toolsmade of stone, bone, or wood. The renownedmuseum of

the Italian natural historianFerrante Imperato contained such arti

facts, including a stone knife from theWest Indies that he illus

trated in the published catalog of his museum in 1599.54Often

ethnographicartifactsfrom theNew World were part of huge col

lections that also contained zoological, botanical, and geological

specimens as well as art objects.55As a result,some natural history

collections contained stone implements fromAmerica as well as

ceraunia. JohnTradescant's famous collection contained several ce

raunia, glossopetrae, and belemnites as part of itsmineral collec

tions and also bows, arrowsand darts fromCanada and Virginia.56

Ulisse Aldrovandi's largemuseum also contained a stone axe given

to him byAntonio Gigas, who said the Indians of America used

them in theirsacrifices. Aldrovandi also owned a stone knife from

America.57Despite having stone implementsfrom theNew World

in his collection it is interestingthatAldrovandi did not emphasize

53) F. Feest, in the

Christian "North America Wunderkammer," Archiv f?r

European

V?lkerkunde,46 (1992), 61-109; Feest, "European Collecting ofAmerican Indian

Artifacts and An," Journal of theHistory ofCollections, 5 (1993), 1-11; Feest, "The

of American Indian Artifacts in 1493-1750," in K. O.

Collecting Europe, Kupper

man, ed., America in Consciousness, 1493-1750 Hill, 1995), 324

European (Chapel

360.

54)Ferrante

Imperato,DelThistoria naturale libriXXVIII (Naples, 1599), 580.

55)

Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and

Scientific Culture

in

Early

Modern Italy (Berkeley,1994);ArthurMacGregor, "TheCabinet ofCuriosities inSev

inOliver

enteenth-Century Britain," Impey and Arthur MacGregor, eds., The Origins

ofMuseums: The Cabinet Curiosities in Sixteenth- and

of Seventeenth-Century Europe

(Oxford, 1985), 147-158.

56) um Tradescantianum:

John Tradescant, Mus Or, A Collection Rarities Preserved

of

at South-Lambeth

Neer London (London, 1656), 22, 45.

57)

Aldrovandi, Museum metallicum, 156, 158.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

500 M.R. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

the similaritybetween these objects and the ceraunia in his collec

tion.

The roleof ethnographicobjects in natural historymuseums and

theirimpacton the interpretation of ceraunia isparticularlyevident

in the case of Robert Plot. Plot was an avid collector and a skilled

natural historian.He was a professorof chemistryat Oxford Uni

versity,and in 1683 he was appointed theKeeper of theAshmolean

Museum at Oxford. This put an immensecollection at his disposal,

including a substantialnumber of geological specimens, as well as

a modest quantityof ethnographicartifactsfrom theAmericas. Plot

was deeply involved in the debate over themeaning of fossilsat the

end of the seventeenthcentury,but he also tackled theproblem of

ceraunia. In TheNatural Historyof Oxford-shire,. published in 1677,

Plot made only a brief referenceto thunderstones,which he de

scribed as having the shape of arrowheads.He noted that theywere

commonly believed to be darts thathad fallen from the skyand for

this reasonhe classifiedthemamong other typesof stones thatorig

inated in the sky.58Plot appears onlyminimally interestedin them

and resorts to the traditional interpretationof theirorigin in his

explanation.However, a decade laterhis thinkinghad changed. By

the timePlot published hisNatural Historyof Stafford-shire in 1686

his interestin natural historyhad expanded to include a broader

interestin antiquities as well.

In the section devoted to the antiquities of Staffordshire,Plot

states that he will only discuss monuments and artifacts "very

remote from the presentAge," which in this case meant objects

belonging to the earlyBritons, Romans, Saxons and Danes.59 Once

again he mentions that flintsin the shape of arrowheadshave been

found in various parts of Britain. One sent to him by theBritish

antiquaryCharles Cotton had a jagged edge and a thickstemwhere

it could be attached to a wooden shaft.Plot also owned a stone

spearhead, given to him by Thomas Gent, anotherBritish collector

of antiquities. But Plot's interpretationof these objects had now

58) The Natural an toward theNatu

Robert Plot, History of Oxford-shire, Being Essay

ralHistory ofFngland (Oxford, 1677), 93.

59)Robert

(Oxford, 1686), 392.

Plot,Natural History ofStafford-shire

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 501

TAflXXXUjL

v', AIVi

Figure 2. Plate XXXIII fromRobert Plot's Natural History of Stafford-shire showing

various British antiquities, including a stone arrowhead, axe, and spearhead in the

upper leftalongwith severalmetal artifactsin theupper right.

completely changed fromhis account of them in 1677. Now he

considered them to be implementsmade by the earlyBritons, and

not thunderstones.60 Plot defended this novel conclusion by citing

Roman authors, especiallyJuliusCaesar, who described theBritons

at the time of theRoman invasionof Britain. According to these

authors, the tribes that lived along the coast used iron,but most

inland tribesdid not,making weapons and tools fromflintinstead.

After scrutinizingthe flintarrowheadsand spearhead he owned Plot

also observed that their surface bore the marks of having been

manufactured.6'Additional support for this idea came

intentionally

from the resemblancethatPlot observed between axe-shaped thun

derstones found in Britain and stone axes from theNew World

60) to me a that the archaeological

Ibid., 396. It has been by colleague

suggested

researches of John Aubrey may have encouraged Plot s interest in antiquities and influ

enced his thinking about stone On researches

implements. Aubreys archaeological

and its impact seeMichael Hunter, JohnAubreyand theRealm ofLearning (London,

1975).

61)

Ibid.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

502 M.R. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

housed in theAshmolean Museum.62 Not unlikeMercati, Plot thus

relied upon a direct knowledge of antiquities, Roman historical

sources,and theobserved physical similaritybetween thunderstones

and New World artifacts.

By contrast,Nehemiah Grew, an English physician and natural

philosopherwho served as Secretaryof theRoyal Society of Lon

don, offersa notable example of a researcherwho had access to

thunderstonesand American stone artifactsbut failed to recognize

any connection between them. In his catalog of the specimens held

in theRoyal Society'smuseum, Grew described an object he called

a "flatbolthead" made of flintand "pointed like a Speer"with ser

rated edges like the head of a "Bearded Dart."63 In everyway he

describes thisobject as if itwere a stone spearhead, but he is quick

to note that natural historians consider these objects to be cerau

nia or thunderbolts,because theyare believed to fall from the sky

during thunderstorms. Grew's response to this idea is that it is not

incredible.64What makes his view so interestingis that elsewhere

in the catalog Grew describes bows and arrows from theWest

Indies, also held in the collection. The arrowshad long cane shafts

tipped with either bone or stone, usually with serrated edges.65

Grew does, however, not have perceived any similarity to cerau

nia.

There are,however,also instanceswhen itwas apparentlynot nec

essary to compare European thunderstones with New World stone

tools to recognize that theywere ancient stone artifacts.In 1656

the English antiquaryWilliam Dugdale recorded the discovery in

what he assumed was a Roman fortnear the village of Oldburie,

inWarwickshire, of some curious flintstones. Theywere shaped like

the head of a pole-axe and had a smooth surface that apparently

was produced by grinding a piece of flintinto the shape of an axe.

62)

Ibid., 396-397.

63) Societatis. Or a & Description

Nehemiah Grew, Musaeum Regalis Catalogue ofthe

Natural and ArtificialRaritiesBelonging to theRoyal Societyand Preservedat Gresham

College (London, 1681), 303.

64)

Ibid., 304.

65)

Ibid., 367.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 503

After this brief description of these objects, Dugdale suggests that

since flintwas an abundantmaterial in this locale, the ancientBrit

ons had used it tomake axe heads, completewith a hole to receive

a wooden handle. Dugdale thought theBritons might have made

weapons of flintbecause theydid not know how to smelt iron or

brass.66One might wonder how Dugdale could have reached such

a matter of factconclusion, given thatother natural historianswere

still treatingthem as thunderstones.Perhaps the answer lies in the

fact thatDugdale was not a natural historian,but an antiquarywho

probably knew theRoman historical sources rather than lapidary

treatises.This may also illuminatewhy Plot revisedhis initial inter

pretation of thunderstones, which was informedby the traditional

natural historical account of them, to his later interpretationthat

relied in part on comparisonswith New World weapons but also

upon Roman descriptionsof the ancient Britons.

Powerful support for the idea that stones of thiskind were an

cient implementsarrivedwhen an ancient sepulcherwas discovered

in July 1685 in the town of Colcherel, in France.Workmen dig

ging for"Free-Stone" to be used for repairsunearthed a tomb con

structedof unhewn stones that contained twentyskeletons.67 Near

the head of one body theworkmen found a piece of yellow flint

thathad been cut into the shape of thehead of a pike, "verysharp

and cutting at both ends and on the sides."Near thehead of a sec

ond body lay a "greenishStone" shaped like thehead of an axe and

having a very sharp edge and a hole piercing one end.68Elsewhere

in the tomb theyfoundmore perforatedaxe heads as well as stones

thatmight have been used as knives and sharpened pieces of bone

thatmight have headed arrows.69Three other small axe heads were

particularlyinterestingbecause itwas apparent that they "were by

66)

William Dugdale, TheAntiquities ofWarwickshireIllustrated;

from Records,Leiger

Books, Manuscripts, Charters, Evidences, Tombs and Arms: with Maps, Pros

Beautified

pects and Portraictures(London, 1656), 778.

67)

Henri Justel, "The Verbal Process upon the Discovery of an Antient in

Sepulchre,

the of Cocherel upon the River Eure in France," Transactions, 16

Village Philosophical

(1686), 221-222.

68)

Ibid., 223.

69)

Ibid., 223-225.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

504 MR. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

Figure 3. Illustrationof the tomb excavated at Cocherel fromHenri Justel'spaper in

thePhilosophicalTransactions(facingp. 226) showing its structureand the arrange

ment of thebodies.

theirnarrow end to be put into a piece of Staggs Horn fitted to

receive them,as appeared by severalpieces found in thisSepulcher,

which had an oval hollow at theend to receiveone of these stones."

These pieces of staghorn had a hole cut in theopposite end so they

could be fastened to a handle. Moreover, itwas apparent that the

horn had been shaped and polished by using a stone and not cut

with iron.70

Henri Justel,a FrenchHuguenot who emigrated to England just

before the revocationof theEdict of Nantes, published an account

of these discoveries in the Philosophical Transactionsof the Royal

Society of London shortlyafter theywere made. Justelhad served

as secretarytoKing Louis XIV before leavingFrance and soon after

his arrival in England became Keeper of theKing's Library at St.

James'sPalace. Justelparticipated in the scientificand philosophi

cal culture of the late seventeenthcenturyand correspondedwith

such figuresas John Locke, Robert Boyle, Edmond Halley, and

Henry Oldenburg. He also published a widely readwork on the

70)

Ibid., 224.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

M.R Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 505

voyages of exploration toAfrica and theAmericas, so he was quite

aware of thecultureof the indigenouspeoples of thesecontinents.7"

Justelbrought a scientist'sand scholar's eye to the problem of the

tomb at Cocherel.

In addition to the stone artifacts,Justelscrutinized the human

skeletons.He noted that theirbones were thickerand strongerthan

the bones ofmodern human skeletons,although theywere of nor

mal stature.But the skeletons appeared to be very ancient.72Be

cause the tombwas constructedof rough stone and therewere no

inscriptionsor carvingson themJustel felt it had to be pre-Chris

tian.Additional support for thisview came from theobjects placed

in the tomb,which indicated a population still immersed in idol

atrous superstition.73Itwas also noteworthy thataround the tomb

burnt bones and asheswere found.From the evidence of thedesign

of the tomb, the presence of stone artifacts,and the featuresof the

skeletons Justelconcluded that theCocherel tomb contained the

bodies of ancient Gauls and thewarriors of some invadingbarba

rous nation who had died in battle.74That thesepeoples were bar

barous was indicatedby the fact that theirweapons were not made

of brass or ironbut insteadwere made of stone and sharpenedbone

just as "some Indian nations do now."75The only matter that

remained unresolved forJustelwas "to guess, by these Stones and

what Antiquitieswe have leftinhistory, who theseBarbarians should

be, and at what time the Sepulcher might be made."76 This sort

of questionwould in fact increasinglybecome the focusof antiquar

ieswho investigatedstone artifactsin the eighteenthcentury.

71) Henri

Justel, Recueil de divers voyages faits en Afrique et en

l'Am?rique: qui n'ont

est? encore contenant coutumes & le commerce des

point publiez: l'origine, les moeurs, les

habitans de ces deux parties du monde: avec des traites curieux touchant la Haute

Ethy

opie, led?bordementduNil, la merRouge,& lePr?te-Jean:le toutenrichidefigures,&

de cartes servent ? es choses contenue en ce volume (Paris,

g?ographiques qui l'intelligence

1674).

72)

Justel, "The Verbal Process upon the Discovery of an Antient 222

Sepulchre,"

223.

73)

Ibid., 225.

74)

Ibid., 226.

75>Ibid.

76) Ibid.

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

506 M.R. Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

Conduding Remarks

The central problem examined in this paper is how earlymodern

natural historiansand antiquaries came to distinguishartifactsfrom

natural objects. The solution to thequestion ofwhat cerauniawere

turnedout to be extremelyimportantfor thehistoryof prehistoric

archaeology as these artifactsbecame sources of evidence about the

earliestperiods of human history.But this followed a difficultpro

cess bywhich ceraunia, understood as stones naturallyproduced in

clouds during thunderstorms,came to be understood as stone arti

factsproduced by people. Few historiansof archaeologyhave inves

tigated the specificevents that led to this importantreinterpretation

of theseobjects, but thedetails of this transformationtellus a great

deal about early archaeology and its relationship to natural his

tory.

The renewed interestin natural history in the sixteenthcentury,

accompanied by the establishmentof natural historymuseums and

the printing of encyclopedic natural history books containing il

lustrationsof specimens,provided an importantcontext for the re

examinationofmany natural objects, including fossilsand ceraunia.

When natural historians such as Gesner and Agricola assembled

collections of ceraunia, described their attributes and compared

differentspecimenswith one another and with earlierpublished de

scriptions,ceraunia as a categoryof stones came under scrutinyand

became betterdefined.A similarprocesswas happeningwith fossils

and we should view these as related events.As the heterogeneous

nature of the category became more apparent natural historians

began to emphasize the formand thematerial of ceraunia.Although

Gesner and Aldrovandi did not argue that theywere hammers

or axes, they did draw the reader's attention to their distinctive

attributes,which included their resemblance to hammers and axes.

This made it much easier for de Boodt to then speculate that

cerauniawere metal tools turned to stone.What seems to have been

the decisive step in the interpretationof these objects was the

comparison of objects known to be axes and arrowheadsmade of

stone from theNew World with ceraunia.Now themorphological

similaritiesrecognizedby Gesner and accepted by de Boodt could

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MR Goodrum/EarlyScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508 507

legitimatelybe used to argue thatcerauniawere thevery same kinds

of stoneweapons and tools.

Ethnographic objects from theAmericas appear to have been

influentialin leadingMercati and Plot to thissurprisingconclusion,

but itmay have been equally importantthat therewere written his

torical sources that supported this interpretation.It was easier to

accept the idea that ceraunia were ancient stone artifactswhen

Roman sourcesmentioned that the earlyBritons used implements

of stone. It is particularlynoteworthy that forantiquaries such as

Dugdale and Justelthe idea that some ancient Europeans had used

stone implementswas not veryproblematic,whereas fornatural his

torians the traditionalnotion that theseobjectswere thunderstones

was an alternative interpretationthathad to be taken seriously.

But once natural historians and antiquaries accepted stone axes

and arrowheads as ancient artifactsentirelynew questions arose,

such as what thismeant for the culture of earlyEuropeans and for

the biblical account of early human history.The recognition that

cerauniawere in factancient artifactsprovided antiquaries and the

nascent science of archaeologywith a new source of evidence about

the earliest ages of human history.Previously,textswere themain

sourceof informationabout thepast and fewworks were considered

to be authentic recordsof themost ancient times.The Bible was

generallyconsidered to be the only reliable source of information

about the origin of human beings and the firstcivilizations,but

great ingenuitywas required to fill in the gaps between the biblical

record and the origins of the firstEuropeans.77Now ancient arti

factsoffereda new source of evidence for investigatingthe remote

past.

More significantly,the presence of stone artifacts throughout

Europe raised troublingquestions about the culture of the indige

77)See Paolo

Rossi, TheDark Abyss ofTime: TheHistory oftheEarth and the

History of

Nations fromHooke toVico tr.Lydia G. Cochrane (Chicago, 1984), chs. 17-36;Mar

garetT Hodgen, EarlyAnthropologyin theSixteenthand Seventeenth Centuries (Phil

adelphia, 1964), chs. 6-9; Don Cameron Allen, The Legend ofNoah: Renaissance

Rationalism in Art, Science and Letters (Urbana, 1963); Arthur B. Utter

Ferguson,

Antiquity:PerceptionofPrehistoryinRenaissanceEngland (Durham, 1993).

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

508 M.R. Goodrum/Early ScienceandMedicine 13 (2008) 482-508

nous inhabitantsof Europe. If these earlyEuropean peoples used

stone implementslike theones used by the inhabitantsof theAmer

icas, did thatmean that earlyEuropeans had also been rude and

savage peoples who lived by hunting,wore animal skins,and lived

in crude dwellings.These were some of theproblems thatantiquar

ies began to investigateduring the eighteenthcentury in thewake

of the general acceptance of the existence of stone artifacts in

Europe.78 The study of ancient stone artifacts,fromEurope and

elsewhere,gave rise in the nineteenth century to the development

of prehistoric archaeology, the formulationof the Three Age Sys

tem thatproposed a prehistoricsuccession of a Stone, Bronze, and

Iron Age, and of the discovery that humans had coexisted with

extinct Ice Age animals.79All of this arose directlyfrom the trans

formationthatoccurred in the seventeenthcentury in the interpre

tationof ceraunia from thunderstonesto ancient artifacts.

78) I this in Matthew R. "The Meaning of 'Ceraunia:

have examined Goodrum,

Natural and the Interpretation of Prehistoric Stone Artifacts in

Archaeology, History,

the Eighteenth Century," BritishJournalfor theHistory ofScience, 35 (2002), 255

269.

79)BarbaraD. a

Lynch and Thomas F. Lynch, "The Beginnings of ScientificApproach

to Prehistoric in Seventeenth-Century and Eighteenth-Century Britain,"

Archaeology

Southwestern Journal ofAnthropology,24 (1968), 33-65; JudithRodden, "TheDevel

opment of theThree Age System:Archaeology's First Paradigm," inGlyn Daniel,

(ed.), TowardsaHistory ofArchaeology(London, 1981), 51-68; Bo Gr?slund, TheBirth

Methods and Dating inNineteenth-Century

of Prehistoric Chronology: Dating Systems

Scandinavian 1987); Peter Rowley-Conwy, From Genesis to

Archaeology (Cambridge,

in

Prehistory:TheArchaeologicalThreeAge Systemand ItsContestedReception Denmark,

Britain, and Ireland (Oxford,2007); Donald K. Grayson, TheEstablishment Human

of

A. Bowdoin Van Men theMammoths: Vic

Antiquity (NewYork, 1983); Riper, among

torian Science and theDiscovery ofHuman Prehistory (Chicago, 1993).

This content downloaded from 31.220.200.77 on Sun, 8 Jun 2014 19:56:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman TimesD'EverandThe First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman TimesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- CerauniaDocument15 pagesCerauniaCatarinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Art and Antiquarian 2011Document34 pagesArt and Antiquarian 2011berixPas encore d'évaluation

- Crombie, A.C.-augustine To Galileo. The History of Science A.D. 400-1650-Harvard University Press (1953)Document467 pagesCrombie, A.C.-augustine To Galileo. The History of Science A.D. 400-1650-Harvard University Press (1953)Edgar Eslava100% (2)

- Alistair Cameron Crombie - Augustine To GalileoDocument461 pagesAlistair Cameron Crombie - Augustine To GalileoRenato F. MerliPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 PaleontologyDocument45 pages10 PaleontologyShenron InamoratoPas encore d'évaluation

- McCown 1972Document4 pagesMcCown 1972Anth5334Pas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeology The Telltale ArtDocument8 pagesArchaeology The Telltale ArtepicneilpatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeology or ArcheologyDocument30 pagesArchaeology or ArcheologySimone WeillPas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeology, or Archeology, Is The Study Of: AntiquariansDocument19 pagesArchaeology, or Archeology, Is The Study Of: AntiquariansAmit TiwariPas encore d'évaluation

- History 2Document13 pagesHistory 2InnocentPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Management Core Concepts 3Rd Edition Full ChapterDocument22 pagesFinancial Management Core Concepts 3Rd Edition Full Chapterandrea.woodard222100% (23)

- Stonehenge: An Ancient Sex Symbol?: Universidades de Cataluña Prueba de Aptitud - Bachillerato LOGSEDocument3 pagesStonehenge: An Ancient Sex Symbol?: Universidades de Cataluña Prueba de Aptitud - Bachillerato LOGSEYvonne CarlilePas encore d'évaluation

- Uk PrehistoryDocument39 pagesUk PrehistoryGaramba Garam100% (1)

- A Short History of Vertebrate Palaeontology - Buffetaut PDFDocument126 pagesA Short History of Vertebrate Palaeontology - Buffetaut PDFDRagonrouge100% (1)

- Transfixed by Prehistory: An Inquiry into Modern Art and TimeD'EverandTransfixed by Prehistory: An Inquiry into Modern Art and TimePas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeology, or ArcheologyDocument22 pagesArchaeology, or Archeologymcoskun1977350Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Hall of The Age of Man: American Museum of Natural HistoryDocument36 pagesThe Hall of The Age of Man: American Museum of Natural Historysunn0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Archeo ReadingspetzDocument2 pagesArcheo Readingspetzapi-326933424Pas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Archaeological Science: ReportsDocument8 pagesJournal of Archaeological Science: ReportsFilip OndrkálPas encore d'évaluation

- Futures Volume 7 Issue 1 1975 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (75) 90034-8) I.F. Clarke - 5. Any More For The Time MachineDocument6 pagesFutures Volume 7 Issue 1 1975 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (75) 90034-8) I.F. Clarke - 5. Any More For The Time MachineManticora VenerabilisPas encore d'évaluation

- Mccurry - 1 - Pride - FinalDocument15 pagesMccurry - 1 - Pride - Finalapi-376486165Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gobekli Tepe Turkey YoutubeDocument4 pagesGobekli Tepe Turkey YoutubeJeanPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of Michael Parker Pearson's Stonehenge - A New UnderstandingD'EverandSummary of Michael Parker Pearson's Stonehenge - A New UnderstandingPas encore d'évaluation

- ArchaeologyDocument120 pagesArchaeologyMaryPher CadioganPas encore d'évaluation

- Archeology The Telltale ArtDocument6 pagesArcheology The Telltale Artapi-674602680Pas encore d'évaluation

- Horn 2019 Review ReinhardDocument6 pagesHorn 2019 Review ReinhardStephany Rodrigues CarraraPas encore d'évaluation

- Cave Hunting-William Boyd DawkinsDocument274 pagesCave Hunting-William Boyd DawkinsAlinPas encore d'évaluation

- RINGKASAN ARKEOLOGI AlionBDocument5 pagesRINGKASAN ARKEOLOGI AlionBAlion BelauPas encore d'évaluation

- Tutankhamen, Egyptomania, and Temporal Enchantment in Interwar Britain-REVISED NEWDocument38 pagesTutankhamen, Egyptomania, and Temporal Enchantment in Interwar Britain-REVISED NEWlui.ricciPas encore d'évaluation

- Petrus Peregrinus': EpistoDocument8 pagesPetrus Peregrinus': EpistoDeborah ValandroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Neolithic of Europe: Penny Bickle, Vicki Cummings, Daniela Hofmann and Joshua PollardDocument4 pagesThe Neolithic of Europe: Penny Bickle, Vicki Cummings, Daniela Hofmann and Joshua PollardbldnPas encore d'évaluation

- John Brock - History of SurveyingDocument11 pagesJohn Brock - History of Surveyingapi-305125951Pas encore d'évaluation

- Momiglinao - Ancient History and The Antiquarian PDFDocument32 pagesMomiglinao - Ancient History and The Antiquarian PDFLorenzo BartalesiPas encore d'évaluation

- Arnaldo Momigliano-Ancient History and The AntiquarianDocument32 pagesArnaldo Momigliano-Ancient History and The AntiquarianNoelia MagnelliPas encore d'évaluation

- History of MagnetismDocument52 pagesHistory of MagnetismMartinAlfonsPas encore d'évaluation

- Grave ShortcomingsDocument35 pagesGrave Shortcomingssol edadPas encore d'évaluation

- The History of Excavation EssayDocument5 pagesThe History of Excavation EssayLiam ByrnePas encore d'évaluation

- The History of Archaeology: "Every View of History Is A Product of Its Own Time"Document54 pagesThe History of Archaeology: "Every View of History Is A Product of Its Own Time"Tobirama1092Pas encore d'évaluation

- Earth's Deep HistoryDocument5 pagesEarth's Deep HistoryProtalinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Goodrum 2016Document23 pagesGoodrum 2016Marcelo Ramos RupayPas encore d'évaluation

- Expeditionary Anthropology: Teamwork, Travel and the ''Science of Man''D'EverandExpeditionary Anthropology: Teamwork, Travel and the ''Science of Man''Pas encore d'évaluation

- Antiquarian LDocument60 pagesAntiquarian LSoumyajit DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Bednarick - Myths About Rock ArtDocument19 pagesBednarick - Myths About Rock Artwhiskyagogo1Pas encore d'évaluation

- From Antiquarian to Archaeologist: The History and Philosophy of ArchaeologyD'EverandFrom Antiquarian to Archaeologist: The History and Philosophy of ArchaeologyPas encore d'évaluation

- CRC 3004-1 Introduction To Archaeology PDFDocument47 pagesCRC 3004-1 Introduction To Archaeology PDFFares Ali100% (1)

- 04 081-126 Borza PalagiaDocument45 pages04 081-126 Borza PalagiakarithessPas encore d'évaluation

- Trigger 1982 - Revolutions in Archaeology CAP 2Document12 pagesTrigger 1982 - Revolutions in Archaeology CAP 2culturammpPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Unsolved Ancient MysteriesDocument5 pages10 Unsolved Ancient MysteriesNhung TâyPas encore d'évaluation

- Chinese Origin Story Pan Gu and The Egg of The WorldDocument31 pagesChinese Origin Story Pan Gu and The Egg of The WorldKenneth Anrie MoralPas encore d'évaluation

- New Neanderthal Remains Associated With The FloweDocument23 pagesNew Neanderthal Remains Associated With The FlowePedro RubianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Men of The Old Stone AgeDocument640 pagesMen of The Old Stone Ageazherjamali123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Geographies of Nineteenth-Century ScienceD'EverandGeographies of Nineteenth-Century ScienceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- 20000-15000BCE SolutreanDocument3 pages20000-15000BCE SolutreanBradley KenneyPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Don't We Call Them Cro-Magnon AnymoreDocument9 pagesWhy Don't We Call Them Cro-Magnon AnymoreyunjanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Apolitìa and Tradition in Julius Evola As Reaction To Nihilism - European Review - 2014Document17 pagesApolitìa and Tradition in Julius Evola As Reaction To Nihilism - European Review - 2014carlos murciaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fascist and The Fox - D - T - Pilgrim 3590887Document48 pagesThe Fascist and The Fox - D - T - Pilgrim 3590887carlos murciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gary Ulmen Carl Schmitt and Donoso CortesDocument11 pagesGary Ulmen Carl Schmitt and Donoso Cortescarlos murciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Social and Political Thought of Julius Evola - Modern Italy - 2014 PDFDocument4 pagesSocial and Political Thought of Julius Evola - Modern Italy - 2014 PDFcarlos murciaPas encore d'évaluation