Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The First Biogeografical Map

Transféré par

Cesar AranaDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The First Biogeografical Map

Transféré par

Cesar AranaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.

) (2006) 33, 761–769

GUEST The first biogeographical map

EDITORIAL

Malte C. Ebach1 and Daniel F. Goujet2

1

Laboratoire Informatique et Systématique ABSTRACT

(LIS), Université Pierre et Marie Curie UMR

Unbeknownst to many historians of biology, the first biogeographical map was

5143 Paléobiodiversité et Paléoenvironnements

Équipe Systématique, Recherche Informatique

published in the third edition of the Flore française by Lamarck and Candolle in

et Structuration des Cladogrammes, 12 rue 1805, the same year in which Humboldt’s famous Essai sur la Geographie

Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France. E-mail: appeared. Lamarck and Candolle’s map marks the beginning of a descriptive or

ebach@ccr.jussieu.fr classificatory biogeography focusing on the study of biota rather than on the

2

Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, distributional pathways of taxa. The map is relevant because it heralds the

Département Histoire de la Terre USM 203- beginning of the creation of biogeographical maps popularized by zoogeogra-

UMR 5143 Paléobiodiversité et phers in the mid- to late nineteenth century together with the study of biogeo-

Paléoenvironnements Équipe Systématique, graphical regions.

Recherche Informatique et Structuration des

Keywords

Cladogrammes, 8 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris,

Biogeographical maps, biogeography, Candolle, Flore française, history of

France

biogeography, Lamarck.

theory of descent (Deszendenzstheorie) was the modus oper-

INTRODUCTION

andi of distributional patterns. Hofsten went as far as declaring

The history of biogeography is poorly known and hitherto has that alternative evolutionary theories such as Rosa’s (1909)

aroused little interest. Only a handful of detailed historical Hologenesis were ‘‘opposed to the biogeographical study of

accounts of biogeography exist that outline its general aims origins’’ (Hofsten, 1916, p. 338, our translation). More

(e.g. Nelson, 1978), its theory (e.g. Kinch, 1980; Richardson, significantly, however, Hofsten declared that ‘‘the biogeo-

1981; Browne, 1983) and its early history (Hofsten, 1916; graphical study of origins has, since the theory of descent, two

Papavero et al., 1997, 2003; Heads, 2005). Nils Gustaf Erland separate but related aims…’’ (Hofsten, 1916, p. 332, our

von Hofsten (1874–1956) presented the first in-depth histor- translation), namely to uncover Earth history and phylogenetic

ical account of distributional studies from Aristotle to Daniele change. Despite Hofsten’s aims, he disagreed with those who

Rosa (Hofsten, 1916). The next seminal work by Nelson believed in different theories of evolution, such as hologenesis.

(1978), details the roles of ecological and historical biogeog- In particular, he disagreed with the Austrian zoologist Ludwig

raphy and their history and influence on late twentieth century Karl Schmarda (1819–1908) and the English ornithologist

comparative biology. The most recent work to rival von Philip Lutley Sclater (1829–1913), who rejected evolutionary

Hofsten (1916) is that of Papavero et al. (1997) (Spanish models in favour of multiple origins.

translation see Papavero et al., 2003), representing the most Sclater, however, had different aims in mind:

comprehensive history of ‘pre-evolutionary’ biogeography to

‘‘Organic beings are not scattered broadcast over the

date.

earth’s surface without regularity or arrangement, as the

All of these works differ in their interpretation of biogeog-

casual observer might suppose, nor are they distributed

raphy. Hofsten in his Zur älteren Geschichte des Disk-

according to the variations of climate or of any other

ontinuitätsproblems in der Biogeographie considered the study

physical external agent, although the latter have, unques-

of distributional pathways on earth as the primary aim of

tionably, much influence in modifying their forms. But

biogeography, in order to solve the problem of disjunct

each species (or assemblage of similar individuals),

distributions (Hofsten, 1916, pp. 197–198, a similar sentiment

whether of the animal or vegetable kingdom, is found

echoed later by Platnick & Nelson, 1978, p. 1). Like other

to occupy a certain definite and continuous geographical

evolutionists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

area on the earth…It thus happens that the various parts

centuries (e.g. Engler, 1879), Hofsten believed that Darwin’s

ª 2006 The Authors www.blackwellpublishing.com/jbi 761

Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01477.x

Guest Editorial

of the world are characterized by possessing special chorology mentioned by the eminent American zoogeographer

groups of animals and vegetables, and that, as a general and mammalogist, Clinton Hart Merriam (1855–1942), who

rule, such tracts of land as are most nearly contiguous considered the study of geographical differences, namely the

have their Faunæ and Floræ most nearly resembling one general change ‘‘that takes place in the fauna and flora in passing

another; while, vice versâ, those that are farthest asunder from one region to another, or from low valleys or plains to high

are inhabited by most different forms of animal and mountains – geographic differences’’ (Merriam, 1892, p. 3), to

vegetable life. When any similar forms, or two regions far be the main focus of biogeography. Merriam understood

apart exhibit similar forms, it is the task of the student of biogeography to be the study of life zones, areas that encompass

geographical distribution to give some reason why this the distribution of organisms (Merriam, 1898). Life zones are

has come about, and so to make the ‘exception prove the equivalent to Lamarck & Candolle’s (1805) floristic provinces

rule’ ’’ (Sclater, 1864, p. 213). (see below), which are analogous to Candolle’s stations, namely

relating ‘‘…essentially to climate, to the terrain of a given

Sclater, too, saw that Earth’s history played an important

place…’’ (Candolle, 1820 in Nelson, 1978, p. 280) that is the

role in defining the geographical regions and modifying the

smaller division within habitations or regions:

organisms that inhabited them. For Sclater, organisms origin-

ated where they are currently found and any discontinuity, that ‘‘In accordance with these facts naturalists long ago began to

is, disjunct distributions, were a result of earth processes. divide the surface of the globe into zoological and botanical

Contrary to the ideas of evolutionists at the time, Sclater regions irrespective of the long recognized geographic

believed that organisms did not disperse to favourable areas, and political divisions’’ (Merriam, 1892, pp. 3–4).

rather they changed over time (modifying their forms) in the

Biogeography, in effect has two histories, not an ecological

same area. The implication of disjunct distributions was,

and historical history (sensu Nelson, 1978), but rather a

therefore, that earth was changing too.

chorological history that uses evolutionary models such as

‘‘To conclude, therefore, granted the hypothesis of the Buffon’s Law (Buffon, 1761) to trace distribution pathways,

derivative origin of species, the anomalies of the and a systematic biogeographical history that describes, com-

Mammal-fauna of Madagascar can best be explained pares, classifies biota and asks ‘‘…whether the continental

by supposing that, anterior to the existence of Africa in areas – the Neartic, the Neotropics, etc. – are real units, or

its present shape, a large continent occupied parts of the whether they are geological and biological conglomerates of

Atlantic and Indian Oceans stretching out towards (what smaller and more local units with diverse histories’’ (Nelson,

is now) America on the west, and to India and its islands 1983, p. 490; see also Ebach & Morrone, 2005). The former is a

on the east; that this continent was broken up into concept that dates as far back as Aristotle (see Aristotle Historia

islands, of which some have become amalgamated with animalium, VIII, pp. 156–165; also see Hofsten, 1916, p. 201,

the present continent of Africa, and some possibly with footnote 1) and was later revised by Buffon (1761) as an

what is now Asia – and that [in] Madagascar and the explanatory law of distribution (see Nelson, 1978, pp. 275–

Mascarene Islands we have existing relics of this great 276). The latter has its beginnings in taxonomy and classifi-

continent, for which as the original focus of the ‘Strips cation of French flora and floristic regions (Lamarck, 1778;

Lemurum’ I should propose the name Lemuria!’’ Lamarck & Candolle, 1805), although the first study was until

(Sclater, 1864, p. 219). now considered by many to have been made by von Humboldt

(1805). Lamarck & Candolle (1805) also mark the initial stages

Surprisingly, exactly 100 years before Croizat (1964), Sclater

of the science of phytogeography, rather than the later work by

had presumed that life and earth evolved together. Whether this

Swiss botanist Alphonse Louis Pierre Pyramus de Candolle

makes Sclater a vicariance biogeographer, or in the case of his

(1806–1893) (Candolle, 1855). Chorology and systematic

super-continent Lemuria, a supporter of continental drift or an

biogeography are equally historical and ecological. The divi-

expanding earth is not a matter for debate here. Although

sion between ecological and historical biogeography is artificial

Sclater (1864, p. 219) coined the term Lemuria he neither

and redundant. The beginning nineteenth century marks a

defined it nor suggested that it sank into the Indian Ocean, as

systematic way of approaching biogeography (phytogeography)

Haeckel believed. Sclater disassociated the discontinuity prob-

that was led by the Swiss botanist Augustin-Pyramus de

lem from evolutionary or migration models. For him, distri-

Candolle (1779–1841), father of Alphonse.

bution was a result of changes in the area that the organisms

Candolle teamed up with fellow naturalist Jean Baptiste

inhabited and not due to migration or dispersal.

Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck (1744–1829)

The striking difference between Hofsten (explanatory bioge-

to write the third edition of Flore française, already an

ography) and Sclater (classificatory biogeography) illustrates the

important work of late eighteenth century botany. Lamarck’s

different aims of biogeography although the latter never

dedication to and knowledge of Linnean taxonomy had

discusses or mentions Haeckel’s chorology, namely the ‘‘the

heralded his first two editions of the Flore française, the

science of the geographic spread of organisms’’ (Haeckel, 1866,

seminal work on botanical taxonomy and classification. Next,

p. 287, translation from Williams, in press), which is clearly what

Lamarck turned to the invertebrates, a term he coined, and

Hofsten’s biogeography was all about. Nor was Haeckel’s

762 Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Guest Editorial

greatly advanced animal taxonomy by separating the crusta- ‘Second Provisional Bio-geographic map of North America

ceans, arachnids and annelids from the poorly described showing the principal Life Areas’. Merriam rarely used the

‘Insecta’. He also provided the most detailed classification of term biogeography again, however, many have since used the

the molluscs. Unfortunately for Lamarck, his theory of term to describe the study of chorology (Williams, in press).

evolution received more attention (through controversy) than Merriam never defined biogeography, although the term was

his botanical and zoological classification and his development at first exclusively associated with the study of life zones and

of this, the first biogeographical map denoting floristic areas of biotic maps. Considering Merriam’s usage of the term,

France. biogeography would have originally been defined as the

Lamarck & Candolle (1805) applied a systematic method classification of the life zones (biota) and endemic areas

through the use of biotic maps, rather than the usual within biogeographical regions, the result of which would be

transverse maps that showed the ecological gradients along a biogeographical map rather than a distributional pathway,

the slopes of mountains (see below). The biotic map ‘‘…is as proposed by Haeckel (1870). If we accept the above

designed to highlight two very different things: 1. the definition, then who produced the first biogeographical

knowledge of vegetation in different parts of France that map?

are known by Botanists and; 2. the general plant distribution Before Merriam’s biogeographical maps, floristic and fau-

on French soil…The second object of this map, namely, to nistic maps were strictly designated as phytogeographical or

show the general distribution of plants in France, precedes zoogeographical, respectively. Merriam (1892) compiled a list

the first in its importance, or at least given our present state of all biogeographical studies that either did or did not include

of knowledge of French flora. The map should be considered maps, starting with Latreille (1817). The first biogeographical

more of an attempt to apply a specific methodology rather maps describing the world regions were the most popular, as

than an attempt to show the complete plant geography of they delimited vast areas defined by climate and larger

France’’ (our italics). geographical features such as oceans or mountain ranges (see

The use of a systematic method, namely to map the Murray, 1866). Smaller scale maps that outlined the faunistic

distributions of biota based on their composition, marks a or floristic areas within a region were rare. Most maps dealt

move away from explanatory distributional models (e.g. with the distributions of single taxa.

Buffon’s Law) toward a formal biotic classification. Mennema (1985) proposed that the Danish botanist

The same systematic approach is not seen in zoogeography Joachim Frederik Schouw (1789–1852) was the first to draw

until 50 years later in the works of English physician James a modern distributional map in his Grundzüge einer

Cowles Prichard (1786–1848), Ludwig Karl Schmarda, Scottish Allgemeinen Pflanzengeographie (Schouw, 1823). According

naturalist Andrew Murray (1812–1878), Philip Lutley Sclater to Mennema (1985), Schouw’s map provides a ‘birds-eye’

and his son, ornithologist William Lutley Sclater (1863–1944) view rather than the earlier transverse views provided by

(Prichard, 1836; Schmarda, 1853; Murray, 1866, Sclater, 1858; Wahlenberg (1812) and Humboldt & Bonpland (1807).

Sclater & Sclater, 1899). The application of a systematic Given the Dane’s ingenuity, Mennema proclaimed that

method in zoogeography led to a plethora of biotic maps, that Schouw ‘‘should be considered the father of plant geography’’

is, biogeographical maps (two terms that will be used (Mennema, 1985, p. 117). The reason given by Mennema was

interchangeably). that Schouw’s map appeared earlier than Candolle’s (1855)

map, which according to Stearn (1951) was the oldest known

biogeographical map. Surprisingly, however, the French

BIOGEOGRAPHICAL MAPS

Abbott Jean-Louis Giraud-Soulavie (1752–1813) drew the

The development of biogeographical maps also reveals a first botanical map with a transverse perspective in 1784,

divergent history. Maps either showed the direction of which is 23 years before the map illustrated by von

distributional pathways (e.g. Engler, 1879, first map; Haeckel, Humboldt & Bonpland (1807). The map entitled Coupe

1866) or they showed the biota (life zones) or regions (e.g. verticale des montagnes vivaroises. Limites respectives des

Engler, 1879, second map; Murray, 1866; Merriam, 1892), the climats des plantes et mesures barométriques de leur hauteur

latter being the more common in the late 19th and early 20th sur le niveau de la Méditerranée (Giraud-Soulavie, 1770–1784)

centuries. shows the succession of flora delimited by latitudinal climatic

Merriam’s interest in distributional maps led to the first gradients. The maps pioneered by Giraud-Soulavie and later

biogeographic map that encompassed all life zones within a drawn by Humboldt & Bonpland and Wahlenberg are

region, in this case the life zones of North America. In order ecological transverse sketches that detail a particular region

to represent the biogeographical regions of North America, or biome in detail, rather than showing the range and variety

mammals were ‘‘chiefly used as illustrations because they of biotic regions as in later biogeographical maps (e.g.

answer the purpose better than any other single group…’’ Merriam, 1892).

(Merriam, 1892, p. 64). In outlining his ‘principles’ Merriam In the third edition of Flore française by Lamarck & Candolle

coined the term biogeography with the heading ‘Principles on (1805), there is a biogeographical map outlining the floristic

which biogeographic regions should be established’. The provinces in France (Fig. 1; a translation of the introduction to

following colour map of North America also carried the title, the biogeographical map within the second volume of the third

Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769 763

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Guest Editorial

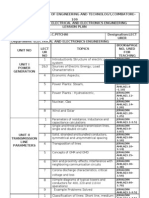

Figure 1 Carte Botanique de France, pour la 3ème Edition de la Flore française par A.G. Dezauche fils Ingénieur Hydrogéologue de la Marine an

13 (1805) ‘Botanical map of France for the 3rd Edition of Flore française by A.G. Dezauche the son, Marine Hydrological Engineer on the

13th year of the Revolution (1805)’ (our translation). Water colour on machine print. Note that Corsica is coloured crimson, which is

characteristic of the 1815 hand painted version.

edition of Flore française is given in Appendix 1). Although the a matter of speculation. This thinking in terms of floristic

existence of such a map has been noted (Nelson, 1978, p. 269, regions and endemic areas may, however, mark the beginnings

footnote 1; Drouin, 1997, p. 249; see Appendix 2) its relevance of studying biotic regions and biogeographical classification,

to phytogeography was understated as it is rarely ever central concepts that Candolle was to develop 15 years later

mentioned in the botanical or biogeographical literature, with (Candolle, 1820).

a few exceptions like Drouin (1997) who notes that the map

appeared in the same year that Humboldt presented his Essai

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

sur la geographie des plantes (Drouin, 1997, p. 249). Perhaps

Lamarck and Candolle’s map was over-shadowed by Hum- We are grateful to M. Didier Geffard-Kuriyama for scanning

boldt’s monumental work (Humboldt, 1805)? Lamarck and Candolle’s map, to Michael Heads and Juan J.

Not only were Lamarck & Candolle (1805) the first to draw Morrone for their comments and suggestions, and to

a biogeographical map depicting floristic provinces, they also Lynne R. Parenti for providing access to the Smithsonian

formulated a systematic method to classify biota (namely, to (Washington DC) copy of the Flore française. We also

map floristic provinces), emphasizing the classificatory nature thank René Zaragüeta i Bagils, David M. Williams, Gareth

of biogeography rather than the study of distributional Nelson, Dennis McCarthy, Antoine Chalubert, Guillaume

pathways. Whether this makes Lamarck and Candolle fathers Dubus and Caitlin E. Hulcup for reading through earlier

or founders of the field of phytogeography or biogeography is drafts.

764 Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Guest Editorial

Lamarck, J.B.P.A. de M. de & Candolle, A.P. de (1805) Flore

REFERENCES

française, ou descriptions succinctes de toutes les plantes qui

Browne, J. (1983) The secular ark: studies in the history of croissent naturellement en France, disposées selon une nou-

biogeography. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. velle méthode d’analyse, et précédées par un exposé des

Buffon, G.L.L. Comte de (1761) Histoire naturelle générale. principes élémentaires de la botanique, 3rd edn. Desray,

Imprimerie Royale, Paris. Paris.

Candolle, A.P. de (1820). Essai élémentaire de géographie Latreille, P.A. (1817) Introduction à la géographie générale des

botanique. Dictionnaire des sciences naturelles, Vol. 18. F. arachnides et des insectes. Mémoires du Muséum d’Histoire

Levrault, Strasbourg. Naturelle, 3, 1–653.

Candolle, A.L.P.P. de (1855) Géographie botanique raisonnée. Mennema, J. (1985) The first plant distribution map. Taxon,

Masson, Paris. 34, 115–117.

Croizat, L. (1964) Space, time, form: the biological synthesis. Merriam, C.H. (1892). The geographical distribution of

Published by the author, Caracas. life in North America with special reference to the

Drouin, J.M. (1997) Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, 1744–1829: sous la Mammalia. Proceedings of the Biological Society of

direction de Goulven Laurent. Congrès National des Sociétés Washington, 7, 1–64.

Historiques et Scientifiques. Section Histoire des Sciences et Merriam, C.H. (1898) Life zones and crop zones of the United

des Techniques. Editions du CTHS, Paris, pp. 241–252. States. US Department of Agriculture Division Biological

Ebach, M.C. & Morrone, J.J. (2005) Forum on historical bio- Survey Bulletin, 10, 1–79.

geography: what is cladistic biogeography? Journal of Bio- Murray, A. (1866) The geographical distribution of mammals.

geography, 32, 2179–2187. Day and Son, London.

Engler, A. (1879) Versuch einer Entwicklungsgeschichte der Nelson, G. (1978) From Candolle to Croizat: comments on the

Pflanzenwelt insbesondere der Florengebiete siet der Tertiär- history of biogeography. Journal of the History of Biology, 11,

periode. Engelmann, Leipzig. 296–305.

Giraud-Soulavie, J.-L. (1770–1784). Histoire naturelle de la Nelson, G. (1983) Vicariance and cladistics: historical per-

France méridionale. Nismes, Paris. spectives with implications for the future. Evolution, time

Haeckel, E. (1866) Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. G. and space: the emergence of the biosphere (ed. by R.W. Sims,

Reimer, Berlin. J.H. Price and P.E.S. Whalley), pp. 467–492. Academic

Haeckel, E. (1870) Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte. Gem- Press, London.

einverständliche wissenschaftliche Vorträge über die Ent- Papavero, N., Martins Teixera, D. & Llorente Bousquets, J.

wicklungslehre im Allgemeinen und diejenige von Darwin, (1997) Història da Biogeografia no Perı́odo Pré-Evolutivo.

Goethe und Lamarck im Besonderen über die Anwendung Plêiade, FAPESP, São Paulo.

derselben auf den Ursprung des Menschen und andere damit Papavero, N., Martinis Teixera, D., Llorente Bousquets, J. &

zusammenhängende Grundfragen der Naturwissenschaft, Bueno Hernandez, A. (2003) Histôria de la biogeografı́a. I. El

Berlin. periodo preévolutivo. Fondo de Cultura Economica, Mexico

Heads, M. (2005) The history and philosophy of panbioge- City.

ography. Regionalización biogeográfica en Iberoamérica y Platnick, N.I. & Nelson, G. (1978) A method of analysis for

tópicos afines (ed. by J. Llorente Bousquets and J.J. Mor- historical biogeography. Systematic Zoology, 27, 1–16.

rone), pp. 67–123, UNAM, Mexico. Prichard, J.C. (1836) Researches into the physical history of

Hofsten, N.G.E. von (1916) Zur älteren Geschichte des Disk- mankind. J. and A. Arch, London.

ontinuitätsproblems in der Biogeographie. Zoologische Richardson, R.A. (1981) Biogeography and the genesis of

Annalen Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Zoologie, 7, 197–353. Darwin’s ideas on transmutation. Journal of the History of

Humboldt, A. von (1805) Essai sur la géographie des Plantes; Biology, 14, 1–41.

Accompagné d’un Tableau Physique des Régions Equinoxiales. Rosa, D. (1909) Saggio di una nuova spegazione dell’origine e

Levrault, Paris. della distribuzione geographica delle specie (Ipotesi della

Humboldt, A. von & Bonpland, A. (1807) Essai sur la géo- ‘‘ologenesi’’). Bollettino dei Musei di Zoologia e Anatomia

graphie des plantes. Levrault, Schoell et Compagnie, Paris. comparata, Torino, Vol. 24 No. 614.

Kinch, M.P. (1980) Geographical distribution and the ori- Saussure, H.-B. de (1779–1796) Voyages dans les Alpes, précédés

gins of life: the development of early nineteenth century d’un essai sur l’histoire naturelle des environs de Genève.

British explanations. Journal of the History of Biology, 13, Fauche, Barde-Manget, Fauche-Borel, Neuchâtel et Genève.

91–119. Schmarda, L.K. (1853) Die geographische Verbreitung der Thi-

Lamarck, J.B.P.A. de M. de (1778) Flore française, ou, Des- ere. Carl Gerold & Sohn, Wien.

cription succinte de toutes les plantes qui croissent naturelle- Schouw, J.F. (1823) Grundzüge einer Allgemeinen Pflanzen-

ment en France: disposée selon une nouvelle méthode geographie. G. Reimer, Berlin.

d’Analyse, & à laquelle on a joint la citation de leurs vertus les Sclater, P.L. (1858) On the general geographical distribution of

moins équivoques en médicine, & de leur utilité dans les arts. the members of the class Aves. Journal of the Proceedings of

L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris. the Linnean Society: Zoology, 2, 130–145.

Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769 765

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Guest Editorial

Sclater, P.L. (1864) The mammals of Madagascar. The Quar- On the map the unknown Western provinces, for example,

terly Journal of Science, 1, 213–219. appear nearly entirely void, thereby calling attention to the need

Sclater, P.L. & Sclater, W.L. (1899) The geography of mammals. for further observation and study. Areas on the map crowded

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., London. with names, however, like the surrounding parts of Paris,

Stafleu, F.A. & Cowan, R.S. (1976–1988). Taxonomic literature Montpellier and Turin [Italy], clearly show that nearly all the

– a selective guide to botanical publications and collections plant content of these areas has been observed.

with dates, commentaries and types, 2nd edn. IDC Publishers, In order to highlight our current knowledge of the French

Leiden. flora, we have noted in capital letters the towns where several

Stearn, W.T. (1951) Mapping the distribution of species. The distinguished botanists have lived and collected (Paris, Mont-

study of the distribution of British plants (ed. by J.E. Lousley), pellier, Turin). Towns labelled in lower case letters indicate the

pp. 48–64. Botanical Society of the British Isles, Oxford. towns and surrounding areas that have a well-known Flora, or

Wahlenberg, G. (1812) Flora lapponica. Berolini, Berlin. several fragmentary ones (e.g. Grenoble, Barrèges and Geneva

Williams, D.M. (in press) Ernst Haeckel and Louis Agassiz: [Geneva at the time being part of France]). Towns labelled with

trees that bite and their geographical dimension. Biogeog- roman letters indicate areas known from incomplete catalogues

raphy in a changing world (ed. by M.C. Ebach and (e.g. Rouen and Soissons). Finally, towns labelled in italics

R. Tangney). CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. indicate floras of neighbouring countries or areas containing

some seedless plants. Given these guidelines, one can, with a

simple map, investigate and determine with precision whether

floras of one or another country are sufficiently known. These

BIOSKETCHES guidelines, quite different from those of ordinary maps, explain

why the names of some villages are written in capitals and those

Malte C. Ebach is a researcher and author in the history and of towns are in smaller fonts, as well as why there is a large

philosophy of comparative biology, Goethe’s way of science, discrepancy between the numbers of villages mentioned in

trilobite taxonomy and systematics at the Laboratoire Informa- different provinces. Due to a lack of space on the map and from a

tique et Systématique, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris. botanical point of view, it has been necessary to exclude several

well-known countries and areas.

Daniel F. Goujet is professor of palaeontology at the The second object of this map, namely to show the general

Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris. His research distribution of plants in France, precedes the first in its

interests include Palaeozoic early vertebrates, mainly Placo- importance, or at least given our present state of knowledge of

derm anatomy and phylogeny, the history and philosophy of French flora. The map should be considered more of an

science and cladistics in all its aspects, and including attempt to apply a specific methodology rather than an

palaeobiogeography. attempt to show the complete plant geography of France.

On this map, France is divided into five regions distin-

guished by different colours; one should note that these areas

Editor: John Lambshead

are not etched into nature exactly as they appear here. It would

be difficult to represent their exact delimitation therefore these

regions have to be considered only as very generalized

APPENDIX 1 ‘EXPLANATION OF THE

indicators.

BOTANICAL MAP OF FRANCE’ FROM FLORE

The area coloured green, marking the coasts from Ostende

F R A N Ç A I S E ( 3 R D E D N , 2 N D V O L . ) B Y L A M A R C K

[Belgium] to Oneille, indicates the realm of maritime [aquatic]

& CANDOLLE (1805), PP. I–XII). A

plants. Other areas marked in green within France, such as the

TRANSLATION OF THE INTRODUCTION

saline lakes of Dieuze, Château-Salins, Salins, Durkheim and

The botanical map of France, which we thought would be a Frankenstatt, indicate that the same aquatic plants occur in

useful addition to this book, is designed to highlight two very places with a sufficient amount of marine salt.

different things: (1) the knowledge of vegetation in different All aquatic plants from northern France are also found on

parts of France that are known by Botanists; and (2) the southern coasts, but the reverse does not occur, and most

general plant distribution on French soil. maritime plants of the Mediterranean realm only grow in small

The main objectives of the map are to help practising field quantities on the ocean border around Gascogne [Bay of

botanists easily orient their research on those points which Biscay] and develop northwards only around the Loire estuary,

have been insufficiently visited, that is, on parts of the flora or, at the very most until the south of Brittany. Despite this

that have not been described in printed works. We will difference, I [A.P. de Candolle, see below] did not think it

therefore know which parts of French flora have been studied necessary to split into two classes the maritime plants, because

in detail. of the extreme similarity we observe in their bearing and their

To give an idea of the different provinces of this vast territory vegetation.

which have been explored by Naturalists, the map will show only The blue colour represents areas in France that are occupied

the names of towns and villages where plants have been collected. by mountain plants. These demarcation lines are less pro-

766 Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Guest Editorial

nounced than in the preceding region. Valleys exposed to the and Western France and in the choice of cultivated plants

sun share the same vegetation of southern provinces, whereas relative to wild plants.

cooler valleys contain plants that are shared with the vast Of all the factors that influence the habitat [l’habita-

northern and central plains of France. These regions, however, tion ¼ ‘physical environment’ or ‘regions’, see Nelson, 1978,

offer a very high number of specific plants, the majority of pp. 280–281] of plants, temperature is without doubt the most

which are present on all mountains. Despite any botanical essential. The latitude and the height above sea level may

differences that may exist between the mountain chains of determine the average temperature of one site, independent of

Vosges, Jura, Alps, Auvergne, Cévennes, Pyrénées, one cannot local conditions. One estimates that in general, areas 200 m

dismiss the fact that aspects of their vegetation offer high traits above sea level have, on average, temperatures that are more or

of similarity and that most mountain plants are found in these less equivalent to one degree of latitude to the North. The

different chains. reader may compare this ratio for the different parts of France

The area coloured crimson red which tints the island of using the lines that we have traced on the map, which indicate

Corsica and the southern parts of France is meant to represent the general altitude of the different provinces relative to sea

the space occupied by the class of plants that I will term level. Mr Dupaintriel’s ingenious idea of applying such a

Mediterranean plants, since they are found in nearly all method to continents, which indicates continental height, is

countries that encircle the Mediterranean sea. One may note the same process that is used on marine charts to indicate

that this area occupies the southern side of our great mountain depths. We copied the heights of French plains and mountains

chains and the space between the sea and the base of from Mr Dupaintriel’s map of France and from the recorded

mountains, spreading a little to the north around Montélimart observations of geologists. The heights of the Alps are extracted

and in the Rhône valley because in the high terrain in this part from the Voyages de De Saussure (Saussure, 1779–1796),

of France there is a higher temperature than in other cities Mr. Ramond communicated those for the Pyrenees and

located at the same latitude. Mr. Léopold de Buch observed those for the Jura.

The vast area in yellow, which covers more than half of If we compare the western and eastern provinces, we see that

France and notably all the plains situated north of the the first are not very high above sea level because, at greater

mountain chains, indicates the uniformity in vegetation of distances from the coast, the altitude is still only 100 m. On the

these large plains. This region contains plants that are similar contrary, the eastern provinces that encircle the mountain

and present in most of the other regions, but lack endemics. chains are generally at four to 500 m above sea level. It is true

The area in vermilion provides us with knowledge of French that this height diminishes at the Belgian side but then

provinces where the vegetation is intermediate between those temperature changes based on a second factor, namely the

of northern plains and those of southern provinces. By a distance from equator. So there is nothing more than

simple inspection of this map one may see that meridional the conformity to laws of physics to explain why plants of the

[southern] plants appear further to the north on the western south appear more northerly on the west than on the east sides.

side than on the eastern side. So, if the floras from Le Mans or Even if the average temperature is the same, the distribution

Nantes1 are studied, it shows they differ only slightly from of plants between these two parts of France should be different

those of Dax and Agen, which are located three of four degrees because of the different way the same temperature is distri-

south of them. On the eastern side, however, floras from Dijon buted among the seasons of the year. It is a generally accepted

and Strasbourg differ totally from those of Aix and Turin fact that, on the same latitude, islands and coastal areas have

although they are located at quite similar distances. more equal temperatures than countries further from the sea.

This fact would appear singular if it were not compared to In other words, they have fewer warmer summers and colder

another observed by Mr Arthur Young. This esteemed winters. The uniform temperature of coastal lands is due to

traveller, who has attentively studied cultivated plants, mild winds and to the proximity to large bodies that have little

remarked that if lines are traced between the northern points variations in temperature. Therefore, the western provinces of

where olive trees, grapes and maize are grown, three nearly France, which all are coastal, benefit by this sort of uniformity

parallel lines are obtained that all tend to meet to the north on that does not affect the eastern provinces that are far away

the eastern side. This is exactly the reverse to what we observe from the seas and closer to the mountains.

for wild plants. We have copied the three lines of Mr Arthur Plants are divided into two classes: those that dislike the harsh

Young, to serve as points of comparison with our divisions. winter cold but do not need the summer heat and those that can

Why there is such an apparent contradiction may be endure cold winters but require hot summers. Included with the

explained by the comparison of the physical nature of Eastern first class are trees (including those that are not conifers) that

retain their leaves and consequently their sap during wintertime.

Most indigenous or acclimatized southern trees that occur in the

1 northern of coastal provinces also belong to this class, including

For the plants of Nantes, I refer to the publication of Mr Bonamy. I

the holm oak, the cork oak, the kermes oak, the arbutus, the bay

learn at the time of publication of this note, that this botanist, without

informing others, has naturalized several exotic plants around Nantes: tree, the fig tree, the philaria and the large flower periwinkle. On

thus this part of the French flora will have to perhaps undergo some the other hand, the second class consists of plants that resist the

revision. harsh winter cold by stopping sap flow and shedding their leaves

Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769 767

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Guest Editorial

(e.g. like the vine, etc.), and those that are able to escape from granitic, the Jura is calcareous and we hardly find plants that

such cold conditions (e.g. maize, etc.). Plants of this second class are not common to both chains. The Jura contains a high

easily acclimatize to the eastern rather than the western parts of number of plants that also grow in the granitic Alps. The Alps,

France. when compared to the high Pyrenees summits, again show that

As for cultivated plants, one should add a last observation both terrains share numerous plants. Furthermore, if we

that is to say that those cultivated to bear fruit are restricted to exclude the very rare plants, we would not find a single

regions with hot summers. Vines for example, are grown for example that is present only in calcareous or granitic terrains.

profit on the southern slopes of the Alps and in places where From the preceding considerations, I believe that in a given

the average temperature is colder than in Brittany or country, such as France, the causes that determine the plant

Normandy, but where summers are very hot and where the region [habitation] could be reduced to three:

grapes will surely ripen. This same shrub is not grown in 1. Temperature, as determined by distance from the equator,

northern France, not because it will die, but because its fruit height above sea level and southern or northerly exposure.

will not ripen since summers are not warm enough. On the 2. The mode of watering, which is more or less the quantity of

contrary, plants that are grown for their fruit, even indigenous water that reaches the plant. The manner by which water is filtered

varieties from the most southern countries, are easily cultiva- through the soil and the matter that is dissolved in the water

ted all over France – as are the artichoke, lavender, the nettle which may or may not be harmful to the growth of the plant.

tree, etc. I need not develop these observations further as they 3. The degree of soil tenacity or mobility.

appear sufficient to explain why, in France, plants from the

south get nearer to the north on the west side than on the east

APPENDIX 2 THE HISTORY OF FLORE

and why several cultivated plants do the reverse.

F R A N Ç A I S E

I place great importance on altitude as a major factor

influencing temperature. I also believe that temperature and not The ‘Flore française, ou descriptions succinctes de toutes les

air density greatly influences vegetation, a factor that well known plantes qui croissent naturellement en France, disposées selon

scientists support. How can you reconcile the influence of air une nouvelle méthode d’analyse, et précédées par un exposé des

density with well known facts? In mountains where the soil principes élémentaires de la botanique, troisième édition’ was

allows a vegetation to grow, plants are found at all attitudes up to the only volume in the series of three editions spanning over half

the permanent snow caps. Plants found in the high Alps are a century that contained a colour map, ‘ouvrage accompagné

found in northern Europe and in places where the air is denser. d’une grande carte botanique coloriée…’. The Flore française

But where the temperature is equal to that of these mountains, survived the French revolution. The first edition published by

these alpine plants can, with certain precautions, be cultivated on the Royal Printers (de l’Imprimerie Royale) in 1778 as three

the lowest plains. Even some of those that grow in the high Alps volumes with Lamarck as the sole author. The second edition,

are found on the coast, and in the same mountains the same printed by H. Agasse in 1795 (l’an 3e. de la République), was ‘‘an

plants grow higher up on the southern slopes than on the almost word by word reprint’’ of the first edition (Stafleu &

northern ones. In temperate zones where the altitude does not Cowan, 1976–1988, p. 732). The third edition grew by two

alone determine the temperature, many anomalies are observed volumes and was ‘‘almost entirely rewritten by Candolle’’ in

relative to the altitude to which these plants are found, although 1805 (Stafleu & Cowan, 1976–1988, p. 442).

very few are noticed in countries close to the equator where the The original third edition of Flore française of 1805 was

altitude alone determines the temperature. Given these facts, I reissued as five volumes in 1815 with a new title page

believe that the temperature level, which varies according to ‘‘…troisième edition, augmentée du tome V, ou sixième

mountain height, influences vegetation. volume, contenant 13000 espèces non décrites dans les cinq

In some texts, importance is placed on the chemical nature premiers volumes’’ and again in 1829, ‘‘but printed by

of soil in which plants grow and, perhaps on further Huzard-Courcier ‘imprimeur depuis 1820’ ’’ (Stafleu & Cow-

consideration, I should have included it on the botanical an, 1976–1988, p. 442). The coloured plate, appearing in the

map. I will however, point out that all the general facts prove second volume and designed for A.G. Dezauche, varies with

otherwise. I do not deny that the nature of the compost, and each reissue of the 3rd edition. The map consists of an original

even sometimes the nature of earth, influences the strength and print that is hand painted with water colours, usually in blue,

properties of plants. What I think can be affirmed, is that this red, crimson, orange, green and aquamarine. In the 1805 print

influence is too insignificant to determine the general region the colours are bright and bold, however in the 1815 prints the

[habitation] of plants, so that plants which flourish on certain colours are washed out pastels. The colours of the south-west

soils can just as well propagate on a different ones, especially region of France differ in both prints, being crimson in the

those that occur nearby. As an example, I will take two of the 1805 edition (as noted by Lamarck and Candolle, above) and a

most characteristic terrains on which the diversity of plants light pink in the 1815 version. One major difference between

have been most clearly delineated – granitic and calcareous them is that Corsica is coloured (pink) in the later 1815 reissue

terrains – and, like in the preceding example, I will use and not coloured at all in the original 1805 print, although

evidence rather than details. In France we have two important designated as so in the introductory text. Another difference

mountain chains that break this assumption: the Vosges are between both reissues is that the 1815 edition makes note that

768 Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Guest Editorial

the 3rd edition contains a map and that the map is located in different parts of the book, either before the introduction, after

the front of the volume. The maps were produced independ- the introduction or in the back (copies viewed: 1805 editions

ently of the text and were inserted afterwards by the binder – Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris; 1815 editions

also a limited number of maps were produced, resulting in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris; Smithsonian

absence of the map in many existing copies of the original 1805 Institution Washington DC; Private Collection of D. Goujet;

edition. The second reprinting of 1815 has the map placed in Private Collection of Anon. No 1829 editions were sighted).

Journal of Biogeography 33, 761–769 769

ª 2006 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Green HydrogenDocument15 pagesGreen HydrogenG.RameshPas encore d'évaluation

- Standard Spreadsheet For Batch ColumnDocument14 pagesStandard Spreadsheet For Batch ColumnBagadi AvinashPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Science GR 7 q1 Week 1 Subtask 1Document17 pagesEnvironmental Science GR 7 q1 Week 1 Subtask 1Majin BuuPas encore d'évaluation

- Datasheet Hybrid H T1 Series Global EN - 1023 - Web 6Document3 pagesDatasheet Hybrid H T1 Series Global EN - 1023 - Web 6Ionut Robert BalasoiuPas encore d'évaluation

- 43a-Intermidiate Check of CRM-chemicalDocument16 pages43a-Intermidiate Check of CRM-chemicalDeepak HolePas encore d'évaluation

- Powerplant Programme 2012Document100 pagesPowerplant Programme 2012JAFEBY100% (1)

- EnvisciDocument7 pagesEnvisciPrecious CabigaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Preface: (Nadeem Irshad Kayani) Programme Director Directorate of Staff Development, PunjabDocument61 pagesPreface: (Nadeem Irshad Kayani) Programme Director Directorate of Staff Development, Punjabsalman khanPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Over Time - Lesson 1Document14 pagesChange Over Time - Lesson 1Nora ClearyPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Sustainability Action PlanDocument15 pagesEnvironmental Sustainability Action PlanIvana NikolicPas encore d'évaluation

- Second Law of ThermodynamicsDocument21 pagesSecond Law of ThermodynamicsVaibhav Vithoba NaikPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of The Arabian Plate PDFDocument60 pagesEvolution of The Arabian Plate PDFscaldasolePas encore d'évaluation

- Description of Indian CoalfieldDocument25 pagesDescription of Indian CoalfieldAjeet KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- CV Robin WaldmanetDocument4 pagesCV Robin Waldmanetyoali2326Pas encore d'évaluation

- Waste Management: Marco Tomasi Morgano, Hans Leibold, Frank Richter, Dieter Stapf, Helmut SeifertDocument9 pagesWaste Management: Marco Tomasi Morgano, Hans Leibold, Frank Richter, Dieter Stapf, Helmut SeifertCarlos AlvarezPas encore d'évaluation

- Renewable Energy Systems (Inter Disciplinary Elective - I)Document2 pagesRenewable Energy Systems (Inter Disciplinary Elective - I)vishallchhayaPas encore d'évaluation

- LIQUIDO-06 Quiz 1Document1 pageLIQUIDO-06 Quiz 1Krexia Mae L. LiquidoPas encore d'évaluation

- AQM M1 Ktunotes - inDocument25 pagesAQM M1 Ktunotes - inBala GopalPas encore d'évaluation

- Power Plant Engineering: TME-801 Unit-IDocument2 pagesPower Plant Engineering: TME-801 Unit-IRe AdhityPas encore d'évaluation

- Ee2303 Newlp ADocument3 pagesEe2303 Newlp ARavi KannappanPas encore d'évaluation

- Study of Use and Adverse Effect of PlasticDocument21 pagesStudy of Use and Adverse Effect of Plasticnishantlekhi590% (1)

- Engineering Geology: Katsuo Sasahara, Naoki SakaiDocument9 pagesEngineering Geology: Katsuo Sasahara, Naoki SakaiRehan HakroPas encore d'évaluation

- Oxidation Mechanism of C in MgO-C Refractory BricksDocument1 pageOxidation Mechanism of C in MgO-C Refractory BricksGisele SilPas encore d'évaluation

- Competency 10Document20 pagesCompetency 10Charis RebanalPas encore d'évaluation

- E8. SBT HK2 (HS) PDFDocument82 pagesE8. SBT HK2 (HS) PDFBùi Thị Doan HằngPas encore d'évaluation

- Physical ScienceDocument5 pagesPhysical ScienceJazz AddPas encore d'évaluation

- Genepax - Water Powered CarDocument2 pagesGenepax - Water Powered CarGaurav Kumar100% (1)

- Sample IB Questions ThermalDocument8 pagesSample IB Questions ThermalEthan KangPas encore d'évaluation

- UCB008Document2 pagesUCB008ishuPas encore d'évaluation