Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Peptic Ulcer

Transféré par

wijeTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Peptic Ulcer

Transféré par

wijeDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Guidelines

Asia-Pacific Working Group consensus on

non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Joseph J Y Sung,1 Francis K L Chan,2 Minhu Chen,3 Jessica Y L Ching,3 K Y Ho,4

Udom Kachintorn,3 Nayoung Kim,5 James Y W Lau,3 Jayaram Menon,3

Abdul Aziz Rani,3 Nageshwar Reddy,3 Jose Sollano,6 Kentaro Sugano,7

Kelvin K F Tsoi,2 Chun Ying Wu,3 Neville Yeomans,3

Namish Vakil,8 K L Goh3

1

Institute of Digestive Disease, ABSTRACT

The Chinese University of Hong Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), especially peptic Significance of this study

Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital,

Shatin, NT, Hong Kong

ulcer bleeding, remains one of the most important cause

2

Department of Medicine & of hospitalisation and mortality world wide. In Asia, What is already known about this subject?

Therapeutics, Asia-Pacific with a high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, < Both Blatchford and Rockall scores are suitable

Working Group, Shatin, Hong a potential difference in drug metabolism, and

Kong for predicting the need for endoscopic interven-

3 a difference in clinical management of UGIB due to tion in upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB).

Asia-Pacific Working Group,

China variable socioeconomic environments, it is considered < Endoscopic intervention within 24 h of onset of

4

Department of Medicine, necessary to re-examine the International Consensus of bleeding improves outcomes in patients at high

Asia-Pacific Working Group, Non-variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding with risk.

National University Hospital, emphasis on data generated from the region. The

Singapore < High-dose intravenous proton pump inhibitors

5

Asia-Pacific Working Group, working group, which comprised experts from 12 (PPIs) are effective in reducing rebleeding from

Korea countries from Asia, recommended the use of the peptic ulcer disease.

6

Asia-Pacific Working Group, Blatchford score for selection of patients who require < PPIs may interact with clopidogrel leading to

Philippines endoscopic intervention and which would allow early

7

Asia-Pacific Working Group, a reduction in antiplatelet activity.

discharge of patients at low risk. Patients’ comorbid

Japan

8

Aurora Summit Medical conditions should be included in risk assessment. What are the new findings?

Center, University of Wisconsin, A pre-endoscopy proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is < To assess the need for endoscopic intervention

Summit, USA recommended as a stop-gap treatment when endoscopy in Asian patients with UGIB, the Blatchford

within 24 h is not available. An adherent clot on a peptic score is preferred.

Correspondence to < When an emergency endoscopy service is

Joseph Sung, Institute of

ulcer should be treated with endoscopy combined with

Digestive Disease, The Chinese a PPI if the clot cannot be removed. Routine repeated available over weekends and public holidays,

University of Hong Kong, Prince endoscopy is not recommended. High-dose intravenous no increased mortality is seen at these times.

of Wales Hospital, Shatin, NT, and oral PPIs are recommended but low-dose < High-dose oral PPIs may be effective in reducing

Hong Kong; intravenous PPIs should be avoided. COX-2 selective rebleeding in Asian patients.

joesung@cuhk.edu.hk < Among patients receiving clopidogrel and aspirin

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs combined with

Revised 9 February 2011 a PPI are recommended for patients with very high risk of as dual treatment, prophylactic use of a PPI is

Accepted 2 March 2011 UGIB. Aspirin should be resumed soon after stabilisation still recommended to reduce the risk of adverse

Published Online First and clopidogrel alone is no safer than aspirin plus a PPI. gastrointestinal (GI) events.

6 April 2011

When dual antiplatelet agents are used, prophylactic use

of a PPI reduces the risk of adverse gastrointestinal

How might it impact on clinical practice in the

events. foreseeable future?

< Endoscopy should be made available in all

practices to provide the service within 24 h of

presentation of upper GI bleeding.

BACKGROUND < When indicated, dual antiplatelet treatment

Although there is a general declining trend in should be prescribed with PPIs in patients

the incidence of peptic ulcer disease, non-variceal who are at high risk for GI bleeding.

upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) remains

a major prevalent and clinically significant condition

world wide. Recent studies suggest that the inci- and draws up consensus guidelines based on the

dence of NVUGIB ranges from 20 to 60 per 100 000 modified Delphi process. It has five sectionsd

population in North America and in Europe,1e3 with namely, 1. resuscitation, risk assessment and

an increasing elderly population with comorbid pre-endoscopy management; 2. endoscopic manage-

illness. ment; 3. pharmacological management; 4. non-

The International Consensus Recommendations pharmacological and non-endoscopic in-hospital

on the Management of Patients with Non-variceal management; 5. postdischarge management,

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (ICON-UGIB) including the use of aspirin and non-steroidal anti-

published in 2010 was a collective wisdom of 34 inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Although the

voters from 15 countries.1 It takes into account the guidelines present comprehensive recommendations

updated literature on the management of NVUGIB and the latest update of the literature, they do not

1170 Gut 2011;60:1170e1177. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Guidelines

allow for the specific needs of resource-limited countries and electronic keypads, until consensus was reached on all state-

differences due to ethnicity. For example, the use of pre-endo- ments. Participants voted anonymously on statements after

scopic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment to down-stage discussion and provided comments on the wording of the

endoscopic lesions and decrease the need for endoscopic inter- statements, which were progressively finalised through two

vention is considered in the ICON-UGIB. This causes financial separate iterations during the 2-day meeting. If there was still no

burden to resource-limited countries in the Asia-Pacific region. consensusdthat is, agreement was <80%, the statement was

High-dose infusion of a PPI is recommended as an adjuvant to rejected. Members also discussed and agreed on the level of

endoscopic treatment but, after considering all the studies evidence for each modified statement. Each statement was

available, the ICON-UGIB did not reach a conclusion about assessed by the following criteria.

the efficacy of either lower intravenous doses or high-dose oral < High. Further research is very unlikely to change our

PPI treatment. Furthermore, there are regional differences in confidence in the estimate of effect.

Helicobacter pylori infection, metabolism of drugs such as PPIs and < Moderate. Further research is likely to have an important

antiplatelet agents, which may have implications for the impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may

management of NVUGIB. change the estimate.

The Asia-Pacific Working Group of Upper Gastrointestinal < Low. Further research is very likely to have an important

Bleeding was a collection of gastroenterologists and surgeons impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is

who are in active clinical practice and research in gastroenter- likely to change the estimate.

ology. They came from 12 countries/regionsdnamely, Australia, < Very low. Any estimate of effect is uncertain.

China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, The conference was underwritten by an unrestricted grant

Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand. The aim of from AstraZeneca Asia. In order to avoid industrial influence

revising the management guidelines for UGIB is to consider the on the process of consensus development, only working

regional differences in patient characteristics and healthcare group members were allowed in the conference room. Manda-

system. Whenever possible, Asian data were used to form the tory written disclosure of financial declared conflicts of

basis of the consensus statement. These guidelines are not interest within the 24 months before the meeting were obtained

meant to cover every detail in the management of NVUGIB. a priori from all voting participants and included in conference

Instead, they highlight the important strategies that may be materials.

more suitable for use in the Asia-Pacific Region. The consensus

meeting was convened in Bangkok in March 2010. CONSENSUS STATEMENTS

A pre-endoscopy prognostic scale is useful to predict patients

METHODS that require endoscopic intervention (agreement: 86.6%, level

Literature searches included Medline, Embase, the Cochrane of evidence: moderate)

Central Register of Controlled Trials and ISI Web of Knowledge The ICON-UGIB states that ‘Prognostic scales are recommended

with manual searches of bibliographies of key articles and for early stratification of patients into low- and high-risk cate-

proceedings of abstracts of major gastroenterology meetings gories for rebleeding and mortality.’1 Indeed, the widely studied

held in the past 5 years (Asian Pacific Digestive Week (APDW), Rockall score2 and Blatchford score3 use clinical, laboratory and

Digestive Disease Week, United European Gastroenterology endoscopic data to predict rebleeding and mortality. However, if

Week). Key words used include gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic scores are used only for prediction of rebleeding and mortality,

ulcer disease and Asia. Studies from Asia were discussed in detail they cannot be applied to the initial management of UGIB. The

for their strengths and weaknesses. The specific features of these Blatchford and pre-endoscopic Rockall scores use only clinical

studies in relation to regional differences were emphasised. and laboratory parameters to identify patients who require

Working group members who came from the 12 countries/ endoscopic intervention. In a recent study from Hong Kong, the

regions mentioned above were selected from the scientific Blatchford and pre-endoscopic Rockall scores were prospectively

committee of the APDW 2010 for their expertise in areas of calculated for all patients and the need for therapeutic endos-

acute UGIB, evidence-based medicine and continuing medical copy was determined.4 One thousand and eighty-seven patients

education and representation of their own country/region. The were included in that study, which showed that those who need

preparation committee in this working group, which comprised endoscopic treatment require a significantly higher Blatchford

Joseph Sung, KL Goh, Francis Chan and James Lau, identified score. It is useful for predicting patients who may not need

statements to be discussed. Based on the modified Delphi endoscopic treatment by using a threshold of 0 (low risk) and

process, the draft statements were sent to all members of the $1 (high risk). On the other hand, although the pre-endoscopic

Asia-Pacific working group, together with evidence-based Rockall score was also significantly higher in those who required

reviews and other pertinent literature. A first round of voting on therapeutic endoscopy than in those who did not, it could not

the statements was conducted by email. Each statement was definitely identify those who required endoscopic treatment at

assessed on a five-point Likert scale: 1. accept completely; a particular score. The disappointing receiver operating charac-

2. accept with some reservation; 3. accept with major reserva- teristic value for the Blatchford score in the Hong Kong study is

tion; 4. reject with reservation; 5. reject completely. Results and at odds with two large UK studies.3 5 The discrepancy is prob-

comments were collated. Agreement with a statement by 80% ably because these UK studies used a broader range of outcomes

of the working group (ie, the proportion of the working group (transfusion, endoscopy and surgery) whereas the Hong Kong

answering 1 plus those answering 2 was $80%) was defined study focused on the need for endoscopic intervention, which is

a priori as consensus. Based on first-round voting comments, the most important clinical parameter in the management of

modifications were made to the statements by a steering UGIB. Therefore, the working group concluded that the

committee comprising Joseph Sung, KL Goh, Udom Kachintorn, Blatchford score should be used to assess the need for endoscopic

Francis Chan, James Lau, Nageshwar Reddy, Neville Yeomans intervention in Asian patients with UGIB. As there is only one

and Namish Vakil. These modified statements were discussed study from Asia to examine this issue, the level of evidence was

during the meeting, followed by a second round of voting with graded as moderate.

Gut 2011;60:1170e1177. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292 1171

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Guidelines

Early discharge of patients with low-risk endoscopic lesions, when early endoscopy or endoscopic expertise is not available

after consideration of comorbid factors, is generally safe and within 24 h. Under these circumstances, pre-endoscopy PPI may

cost saving (agreement: 100%, level of evidence: moderate to buy time to stabilise patients before definitive treatment can be

low) arranged. This may be the case for some countries or commu-

Can we triage patients for outpatient care or early discharge nities in Asia, especially in rural areas, when medical facilities are

after hospitalisation based on their clinical and endoscopic limited or in countries where only licensed endoscopists are

findings? The Rockall score provide useful endoscopic criteria for allowed to perform therapeutic endoscopy. In the Hong Kong

a patient at low risk. Two studies from Asia have confirmed also study,11 the mean time to endoscopy after the start of intrave-

that early discharge is possible without increasing the risk of nous PPI infusion was <24 h in both PPI and placebo groups of

morbidity and mortality.6 7 Yet these are cohort studies and data patients. No randomised study has been carried out to compare

from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are scanty. Two small- pre-emptive PPI against early endoscopy, and thus the recom-

scale prospective randomised trials from Europe suggested that mendation can only be based on logical deduction and expert

early discharge of these patients from hospital did not affect opinion.

the need for surgery and mortality of patients.8 9 A recent

prospective cohort study from Hong Kong also found that Endoscopic intervention within 24 h of onset of bleeding

a Blatchford score of 0 is a good indicator of patients at low risk, improves outcomes in patients at high risk (agreement: 100%,

who can be discharged without admission as these patients do level of evidence: moderate)

not require endoscopic intervention.4 However, one must Early endoscopy has been advocated for the management of

differentiate between patients with ulcers at low risk for UGIB but the optimal timing is still debated. Most of the data

rebleeding against patients at low risk for mortality. As a survey in available are based on retrospective cohorts. Only three rando-

over 10 000 cases of peptic ulcer bleeding in Hong Kong showed mised trials are available, two of which came from Asia.14e16 A

three-quarters of patients died not because of uncontrolled or systematic review concluded that endoscopy within 12 h or

recurrent bleeding, but because of non-bleeding causes such as earlier does not result in a better clinical outcome.17 There is no

cardiopulmonary decompensation and multi-organ failure10; improvement in mortality, reduction in surgical need or reduced

patients may have ulcers with a low risk for recurrent bleeding requirement for blood transfusion and very early endoscopy

but die from comorbid conditions. Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding often leads to increased use of endoscopic treatment for

may represents a terminal event in the multi-organ system advanced signs of haemorrhage, which may not be necessary.17

failure. The endoscopic scoring may not apply to low-risk lesions Endoscopy within 24 h of presentation is recommended for

in patients at high risk with multiple comorbidities. Patients management of UGIB. In most centres in developed countries,

may have a low risk for a rebleeding ulcer but age and comorbid an endoscopy service is available throughout the week but not

illness determine their risk of dying. Therefore, in this state- necessarily over the weekends and public holidays. Three studies

ment, the working group specifies in patients with low-risk from the USA recently indicated that patients with UGIB

endoscopic lesions that due consideration should be given to the admitted over the weekends have a higher mortality, probably

comorbid conditions of the patients. As there is a lack of large- related to the longer endoscopy waiting time.18e20 In Asia, when

scale randomised trials examining this subject, the level of an emergency endoscopy service is available over weekends and

evidence was graded as moderate to low. Further studies in this public holidays, this ‘weekend effect’ is not evident.21 Therefore,

area are warranted. the working group recommends that all hospitals provide

sufficient resources for an endoscopy service that can offer an

Pre-endoscopy proton pump inhibitor is recommended where examination within 24 h after patient presentation, including

early endoscopy or endoscopic expertise is not available within weekends and holidays. The working group discussed two

24 h (agreement: 86.7%, level of evidence: low) exceptional circumstances in which urgent endoscopy should be

A large single-centre randomised controlled study showed that considered. In patients at very high risk who are haemody-

pre-endoscopic use of PPIs at a high dose can downgrade the namically unstable and in patients presenting with massive

signs of haemorrhage of peptic ulcer disease.11 As a result, fewer haematemesis, endoscopy should be performed as soon as

patients required endoscopic intervention. However, the use of patients are stabilised with resuscitation. On the other hand, in

PPIs under such conditions does not translate into reduction in patients who have critical cardiopulmonary conditions, endos-

recurrent bleeding, surgery and mortality rates. This finding was copy should be postponed until the blood pressure, heart rate

consolidated by a subsequent meta-analysis.12 The ICON-UGIB and oxygenation of blood is stabilised. More randomised study

guidelines stated that “pre-endoscopic PPI treatment may be to investigate the timing of endoscopy is necessary.

considered to downstage the endoscopic lesion and decrease the

need for endoscopic intervention but should not delay endos- Endoscopic treatment plus PPI is preferable to a PPI alone in

copy.”1 This working group has deliberated on the implications ulcers with adherent clots resistant to vigorous irrigation

of this statement and found that it fails to point to a specific (agreement: 86.7%, level of evidence: moderate to low)

strategy in the acute management of UGIB. Should a pre- The optimal endoscopic treatment for a peptic ulcer with an

emptive PPI be routinely given to all patients presenting with adherent blood clot is controversial. The ICON-UGIB included

symptoms and signs of UGIB, or should it be recommended only two statements on this topic but the conclusion is still ambig-

for a selected population? The recommendation should not be uous. ‘The finding of a clot in an ulcer bed warrants targeted

constructed as discouraging clinicians who use pre-emptive PPIs irrigation in an attempt at dislodgement with appropriate

for all patients with UGIB. In fact, in a decision analysis based treatment of the underlying lesions.’1 On the other hand, ‘the

on the Hong Kong model, the use of a high-dose PPI before role of endoscopic treatment for ulcers with adherent clot is

endoscopy increases the upfront cost but reduces subsequent controversial. Endoscopic treatment may be considered,

procedures and hence duration of hospital stay, and thus is still although intensive PPI treatment may be sufficient.’1 The diffi-

a cost-effective measure.13 However, the working group culty in this scenario is that if a clot is removable, and an

considered that a pre-endoscopy PPI may be valuable in practices underlying protuberant vessel is exposed, there is little doubt

1172 Gut 2011;60:1170e1177. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Guidelines

that it should be treated with either thermal coagulation or make a difference.31 Less recurrent bleeding was reported after

clips.22 However, there are occasions that the clot cannot be repeated thermal coagulation (4.3%) than single endoscopy

removed even with vigorous targeted irrigation. Not all endo- (15.7%). Unlikely thermal coagulation, second-look endoscopy

scopists are comfortable to cheese-wire an adherent clot using with repeated injection treatment did not prevent rebleeding

a polypectomy snare in case it will provoke bleeding that cannot (17.6%) in comparison with the single treatment (20.8%). The

be stopped. To complicate the issue further, it is well known ICON-UGIB stated that ‘routine second-look endoscopy is not

that sometimes it is difficult to distinguish a clot from a protu- recommended’.1 This panel considers that there is room for

berant vessel.23 Furthermore, the definition of adherent clot is further research in this area to identify a specific group of

not clearly defined. In practical terms, it is also difficult to patients for whom second-look endoscopy with definitive

calibrate both the vigour of irrigation and the length of time for haemostasis with a thermal or mechanical device may be

which irrigation should be attempted before announcing failure beneficial.

to remove clot. In a recent post hoc analysis based on the PUB

study,24 the risk of recurrent bleeding was found to be higher in As an adjunct to endoscopic treatment

patients with peptic ulcer with an adherent clot (17.6% re-bled A. A high-dose intravenous (IV) PPI is effective in reducing

within 72 h OR¼4.12, 95% CI 1.27 to 13.3) than in those with rebleeding and the need for surgery (agreement: 100%, level

a protuberant blood vessel (11.3% re-bled within 72 h, OR¼2.62, of evidence: high).

95% CI 1.05 to 6.54).25 B. A high-dose oral PPI may be effective in reducing rebleeding

Based on a meta-analysis which included six studies repre- in Asian patients (agreement: 93.3%, level of evidence:

senting 240 patients from the USA, Hong Kong, South Korea moderate).

and Spain, endoscopic treatment is considered better than C. Insufficient data exist on low-dose IV PPI to justify its use

medical treatment for prevention of recurrent haemorrhage in (agreement: 100%, level of evidence: moderate to low).

patients with bleeding peptic ulcers and adherent clot.26 The An IV bolus followed by infusion of a high-dose PPI reduces

study was criticised for combining studies with a variable study recurrent bleeding, need for repeated endoscopy, surgery and

design and hence the summary statistics may be misleading.27 blood transfusion. This is evident in the Cochrane meta-analysis

Recurrent bleeding is likely to be reduced and requirement for of data, including 24 RCTs,32 33 which showed that even

surgery decline after endoscopic intervention only in popula- mortality is reduced with the use of intravenous high-dose PPIs.

tions with a high rate of rebleeding after removing clots27 and Indeed, high-dose PPI infusion has already been adopted as

Asian populations belongs to this category.24 a standard of care in many Western countries. The initial

Based on existing evidence, the working group recommended discrepancy between European and Asian studies has also been

vigorous target irrigation of a blood clot covering peptic ulcers resolved by a multinational prospective randomised trial using

for at least 5 min. For an adherent clot resistant to irrigation, esomeprazole in the high-dose infusion regimen in the PUB

endoscopy combined with injection treatment and thermal study.24 The mortality in that study was relatively low and may

coagulation or mechanical device would be applied together not entirely reflect the real-life situation where peptic ulcer

with a PPI. There may be a chance of overtreating some patients bleeding is managed in smaller centres with less experience. The

who have a low risk of recurrent bleeding. However, existing use of high-dose intravenous PPIs has also been found to be cost

evidence cannot differentiate between high-risk and low-risk effective in both Asia and America.34 35

blood vessels at the base of peptic ulcer. Further studies are One interesting observation in the PUB study is that a post

needed to support this recommendation. hoc analysis suggested that the benefit of PPI is greater in those

who have H pylori infection (rebleeding rate dropped from 8.4%

Second-look endoscopy is not routinely recommended after to 3.7%) than in those who did not have the infection

endoscopic haemostasis but should be reserved for selected (rebleeding rate dropped from 11.8% to 9.8%).24 This finding

patients at high risk for rebleeding (agreement: 93.3%, level of implies that H pylori infected patients may have a lower acid

evidence: moderate to low) output and hence an augmented effect of acid suppression by

The benefit of routine repeat endoscopy after endoscopic PPIs. Thus it is not difficult to understand that in some Asian

haemostasis in the management of UGIB is another contentious studies, even oral PPIs have been found to be useful in

area. Evidence for so-called second-look endoscopy is based preventing recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcers.36e40 Although

mostly on small-scale studies. While routine second-look the Cochrane pooled data showed that only high-dose IV PPIs,

endoscopy may not benefit all patients with UGIB, a selected but not oral PPIs or low-dose IV PPIs, benefit patients and result

population of patients at high risk may be benefit from this in improved clinical outcome, there are obvious differences

strategy.28 Overall, the outcome measurement including recur- between Asian and non-Asian studies.32 33 Two studies from

rent bleeding, surgery, mortality, blood transfusion and length of Asia showed that oral PPIs as an adjunct to endoscopic treat-

hospital stay are not improved by the use of routine second-look ment reduced the risk of recurrent bleeding. Javid et al used oral

endoscopy.29 In a randomised study from Hong Kong comparing omeprazole 40 mg twice daily for 5 days and found that recur-

routine second-look endoscopy with repeated treatment versus rent bleeding was reduced from 21% to 7%.39 Kaviani et al also

routine use of high-dose PPIs, the recurrent bleeding rates at found that oral omeprazole 20 mg given every 6 h for 5 days

3 days, 1 week and 1 month between the two groups were reduced recurrent bleeding by almost 50%.40 This observation is

almost identical.30 There is no difference in transfusion also considered in the ICON-UGIB, which suggest that oral

requirement, surgical operation or mortality using the two doses of PPIs equivalent to four times the standard daily oral

strategies. However, as more data become available and are dose can be considered.1

pooled in a meta-analysis, with the endoscopic treatment being Although strong evidence demonstrates the efficacy of high-

combined with injection treatment (which provides only dose IV PPI treatment after successful endoscopy, it is not

temporary haemostasis) or thermal coagulation (which provides possible to draw definite conclusions about the efficacy of

more definitive haemostasis), there is evidence suggesting that a lower IV dose of PPI. Meta-analysis by Laine and McQuaid

routine second-look endoscopy with thermal treatment may found that lower doses of PPIs may reduce rebleeding compared

Gut 2011;60:1170e1177. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292 1173

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Guidelines

with placebo or no treatment.41 A recent meta-analysis to find a treatment strategy to further reduce risk of recurrent

comparing high-dose and non-high-dose PPIs after endoscopic bleeding from peptic ulcers with the use of analgesics. In

treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers42 concluded a randomised controlled study from Asia, in which H pylori

that there was no difference in the outcome. The study, negative patients with a history of peptic ulcer bleeding were

however, was limited by multiple methodological flaws, such as assigned to receive either celecoxib 200 mg twice daily plus

including inappropriate studies and insufficient sample size.43 In esomeprazole twice daily or celecoxib 200 mg twice daily plus

Korea, studies comparing low-dose IV PPIs with a standard high- placebo, recurrent rebleeding was reported in almost 9% in the

dose regimen have been carried out but the results are placebo group but 0% in the PPI group.50 A similar study using

conflicting.44 Head-to-head comparisons and subgroup analysis celecoxib 200 mg daily in comparison with naproxen 750 mg

of high versus lower IV doses are also underpowered. Therefore, daily plus lansoprazole 30 mg daily produced an almost identical

a low-dose regimen of IV bolus or infusion of PPIs cannot be resultdthat is, the rates of ulcer complications were similar but

recommended. still substantial.51 However, a head-to-head comparison of

a COX-2 selective NSAID plus PPI and an NSAID plus PPI is

Angiographic embolisation should be considered as an lacking. Despite this limitation, a COX-2 selective NSAID plus

alternative to surgery in patients for whom endoscopic PPI probably offers the best available option because this

haemostatic treatment has failed (agreement: 100%, level of strategy has been shown to be better than a COX-2 selective

evidence: low) NSAID alone50 and there is evidence that NSAIDs plus PPIs

When a first endoscopy fails to control peptic ulcer bleeding, provide upper GI protection equivalent to that of a COX-2

surgery offers a better chance to secure haemostasis but repeated inhibitor alone.49

endoscopic treatment carries fewer complications.45 However,

because of advanced age and serious comorbid illnesses, not all Among aspirin users with high cardiothrombotic risk who

patients are suitable candidates for surgery. Angiographic develop ulcer bleeding, aspirin should be resumed as soon as

embolisation has been used in the treatment of peptic ulcer possible once haemostasis is established (agreement: 86.6%,

bleeding. In a French series of 60 patients, embolisation treat- level of evidence: moderate)

ment controlled gastroduodenal bleeding in 95% of cases after Discontinuing antiplatelet treatment in patients with high

endoscopic failure.46 There is no solid evidence to support the cardiothrombotic risk increases the likelihood of occurrence of

use of angiographic embolisation as an alternative to surgery an adverse cardiovascular event. This phenomenon has been well

after endoscopic treatment has failed to control bleeding of demonstrated in a small retrospective study52 and more recently

UGIB. A retrospective study from Italy showed no significant a prospective RCT.53 This Asian study added a high-dose intra-

differences between embolisation treatment and surgery for venous PPI followed by an oral PPI to low-dose aspirin, and

rates of rebleeding, surgery or mortality.47 Another retrospective showed that patients whose aspirin treatment was discontinued

study from Hong Kong also showed that angiographic emboli- after endoscopic haemostasis of ulcer bleeding had a lower risk

sation is valuable for uncontrolled ulcer bleeding.48 Gelatin of recurrent bleeding but significantly higher mortality. Most of

sponges, polyvinyl alcohol, cyanoacrylate have been used for the mortality was related to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular

embolisation but coils are most commonly used. It is well death. In this study, however, the prolonged discontinuation of

known that because of the vascular nature of the stomach and aspirin for 8 weeks was a concern. There was no evidence to

duodenum, more than one vessel will often need to be embolised suggest that discontinuation for 30 days or shorter will increase

to control bleeding. Recurrence of bleeding after a successful mortality. Currently, there is a lack of clinical data to provide

procedure is not uncommon. The working group recommends guidance on a ‘safe’ period of discontinuation of aspirin or

that clinicians should consider angiographic embolisation as antiplatelet agents. Given the evidence of potential harm asso-

a possible alternative treatment, especially for patients with ciated with discontinuation of antiplatelet agents, the working

high surgical risk. Since there is a lack of solid evidence, the group recommends that aspirin should be resumed as soon as

working group suggests that angiographic embolisation should possible after achieving endoscopic haemostasis within a few

be considered as an alternative only if expertise is available. A days after endoscopy. As the first 3 days after index bleeding

prospective randomised study is urgently needed to shed light on account for about 80% of rebleeding occurrence,53 and as the

the efficacy of this treatment. antiplatelet activity of aspirin is irreversible until new platelets

are being produced in the bone marrow, it is sensible to restart

Among patients with arthritis and a history of ulcer bleeding aspirin at day 3e5 provided that the patient’s haemodynamic

who require NSAIDs condition is stable.

A. Both non-selective NSAID plus a PPI and a COX-2 selective Data are lacking in the literature to indicate whether patients

NSAID reduce rebleeding but substantial risk remains receiving clopidogrel should also resume the drug early after

(agreement: 100%, level of evidence: high). bleeding is brought under control. In view of the similar anti-

B. A COX-2 selective NSAID plus a PPI offers the best available platelet activity of clopidogrel and aspirin, it might be prudent

upper GI protection (agreement: 100%, level of evidence: to stop clopidogrel also for 3e5 days and resume after stabili-

moderate). sation. There is also no evidence to guide the treatment of

It is known that in patients who have a history of peptic ulcer patients taking dual antiplatelet agents (eg, aspirin plus clopi-

bleeding, the use of both a COX-2 selective NSAID and an dogrel) who develop upper GI bleeding. Patients receiving

NSAID plus a PPI have reduced but not eliminated risk of clopidogrel usually have a previous coronary stent placement.

recurrent bleeding. In a study which randomised patients to The optimal timing of resuming clopidogrel or dual antiplatelet

receive either diclofenac 75 mg twice daily plus omeprazole treatment needs to be individualised because it depends on the

20 mg per day or celecoxib 200 mg twice daily,49 over a period of duration of stent placement (eg, a coronary stent placed within

6 months, rebleeding occurred in 6.4% and 4.9%, and recurrent 30 days carries a much higher risk of thrombosis than a stent

ulcer reported in 26% and 19%, respectively. These are still placed beyond 30 days), the type of stent (ie, drug-eluting vs

substantial proportions of patients and therefore, it is necessary bare metal stents) and, probably, the ease of endoscopic

1174 Gut 2011;60:1170e1177. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Guidelines

haemostasis. It is therefore not possible to draw up any prescribed a PPI in addition to a dual antiplatelet agent may

consensus statement on the discontinuation of clopidogrel or merely reflect the fact that those patients had more serious

dual antiplatelet agents in the acute phase of upper GI bleeding. comorbid illness and therefore a PPI is merely a surrogate for more

Further studies are urgently needed in this area. serious morbid illness. In a meta-analysis of 23 studies involving

over 93 000 patients, analysis of propensity-matched or randomised

Clopidogrel alone is not a safer alternative than the combination trials showed no association between cardiovascular risk and PPI

of low-dose aspirin plus PPI in patients with increased risk of use. In contrast, other observational studies showed a significant

ulcer bleeding (agreement: 100%, level of evidence: moderate) association. It is worthwhile pointing out that the meta-analysis

With the ageing population world wide, many patients with did not show significant association between PPI use and overall

cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases require long-term anti- mortality.68 As indicated by an editorial recently, however, the

platelet agents to prevent vascular thrombosis. The CAPRIE existing regulatory decisions are not based on quality clinical

study, with a large study population and careful study design, has studies and have relied more on surrogate markers such as in vitro

convincingly shown that clopidogrel is a safer drug to use than platelet-inhibition studies.69 The only way to settle this issue is to

aspirin in patients with vascular disorder, leading to less GI conduct a carefully designed randomised study comparing dual

bleeding.54 However, it is worth pointing out that the CAPRIE antiplatelet agents (including clopidogrel) with or without a PPI for

study targeted a population at average risk rather than patients at cardiovascular and GI adverse events. This was indeed done in the

high risk for UGIB. Conversely, it has been shown that patients COGENT trial which was designed specifically to examine this

receiving clopidogrel had an increased incidence of recurrent upper topic.70 This multicentre randomised double-blind, double-

GI bleeding than patients receiving low-dose aspirin combined dummy, placebo-controlled study showed that PPIs reduced GI

with a PPI. In an Asian randomised controlled study recruiting bleeding but did not increase cardiovascular risk. Unfortunately, the

patients with a history of peptic ulcer bleeding who required study was terminated prematurely for financial reasons. Although

antiplatelet agents, clopidogrel increased the risk of recurrent this was an unfinished trial with incomplete enrolment and trun-

bleeding more than 10 times.55 However, the incidence of lower cated followed up of up to 133 days (median follow-up), the result

GI bleeding was the same with or without a PPI. Therefore, a PPI gave the best available evidence that the interaction between a PPI

protects the upper GI tract from further injury by aspirin and the and clopidogrel has, at most, a modest effect on thrombosis. Based

combination is safer than clopidogrel monotherapy. In this study, on these results, the working group recommends adding a PPI to

aspirin 80 mg daily was used. A similar study also from Hong dual antiplatelet agents when indicated.

Kong using esomeprazole 20 mg and aspirin 100 mg per day

versus clopidogrel 75 mg daily in patients with history of peptic FUTURE RESEARCH

ulcer bleeding and treated H pylori infection showed a similar The management of upper GI bleeding has come a long way

result.56 The risk of upper GI bleeding with low-dose aspirin is from the advent of endoscopic treatment, use of potent acid-

dose related.57 It is uncertain whether PPIs can confer the same suppressing agents and the complications of NSAID and anti-

degree of protection as higher doses of aspirin. Irrespective of the platelet usage. There is a pressing need for future studies to

practice in Asian or Western countries, it is generally agreed that elucidate the effect of oral high-dose PPIs in prevention of

there is no added cardiovascular benefit of using aspirin beyond recurrent bleeding, the optimal period of discontinuation of

160 mg daily. The interaction of clopidogrel and a PPI may aspirin, the best protection for those who require double anti-

hamper the antiplatelet activity of the former and hence is not platelet agents. On the endoscopic front, a simple scoring

favoured. The working group also discussed the cost of aspirin system to identify high-risk patients for endoscopic interven-

plus a PPI in comparison with clopidogrel; the former prescription tion, the role of angiographic embolisation when endoscopy fails

is cheaper in most Asian countries. to control bleeding, the selection criteria for high-risk patients

who may require second-look endoscopy will be important

Among patients receiving clopidogrel and aspirin as dual future topics for research.

treatment, prophylactic use of a PPI reduces the risk of adverse

GI events (agreement: 81.25%, level of evidence: moderate) DISSEMINATION STRATEGIES

Use of dual antiplatelet agents is increasing as patients with This consensus statement which is tailored for the Asian

acute coronary syndrome treated by coronary stenting are population will be disseminated by the following means:

prescribed a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel for up to 1. presentations at future APDW meetings as forums to an

12 months based on the PCI-CURE study.58 In the same study, audience of predominantly Asian clinicians and 2. copies of this

however, it is obvious that the two antiplatelet agents together statement will be sent to national societies/associations of

increase the risk of major GI bleeding from 0.7% to 1.3%. Yet, gastroenterology and endoscopists for their iteration and

clopidogrel, a prodrug that needs to be metabolised in the liver dissemination. It is hope that the consensus strategies will be

by cytochrome P450 system (particularly 2C19), competes with updated regularly and adopted by health authorities in the

PPIs, which are also metabolised by CYP2C19, and this has Asia-Pacific region to improve the care of patients with UGIB.

raised major concern. Loss of antiplatelet effect due to this

Funding AstraZenec Asia.

biological interaction has been demonstrated in ex vivo studies

on the platelet reactivity index.59e61 Retrospective caseecontrol Correction notice This article has been corrected since it was published Online First.

and cohort studies also indicated that PPI use leads to increased The name of one of the authors was corrected in the author list.

thrombosis of coronary stents and is associated with increase Competing interests None.

recurrent myocardial infarction.62e65 On the other hand, other Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

studies reported no such association.66 67

One of the explanations of this conflicting result is that the

REFERENCES

studies are mostly retrospective cohort studies in which risk 1. Barkun A, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, et al. International consensus recommendations

factors for cardiovascular diseases such as smoking, hypertension, on the management of patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding

cholesterol levels, etc, were not controlled. Patients who were (ICON-UGIB). Ann Intern Med 2010;152:101e13.

Gut 2011;60:1170e1177. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292 1175

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Guidelines

2. Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, et al. Risk assessment after acute upper 31. Tsoi KK, Chan HC, Chiu PW, et al. Second-look endoscopy with thermal coagulation

gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 1996;38:316e21. or injections for peptic ulcer bleeding: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol

3. Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment 2010;25:8e13.

for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet 2000;356:1318e21. 32. Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Proton pump inhibitor treatment for acute

4. Pang SH, Ching JY, Lau JY, et al. Comparing the Blatchford and pre-endoscopic peptic ulcer bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD002094.

Rockall score in predicting the need for endoscopic therapy in patients with upper GI 33. Leontiadis G, Martin J, Sharma V, et al. Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment for

hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:1134e40. peptic ulcer (PU) bleeding: an updated Cochrane metaanalysis of randomized

5. Stanley AJ, Ashley D, Dalton HR, et al. Outpatient management of patients with controlled trials (RCTs). Gastroenterology 2009;136:A134.

low-risk upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage: multicentre validation and prospective 34. Barkun AN, Herba K, Adam V, et al. High-dose intravenous proton pump inhibition

evaluation. Lancet 2009;373:42e7. following endoscopic therapy in the acute management of patients with bleeding

6. Lai KC, Hui WM, Wong BC, et al. A retrospective and prospective study on the peptic ulcers in the USA and Canada: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Aliment

safety of discharging selected patients with duodenal ulcer bleeding on the same day Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:591e600.

as endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1997;45:26e30. 35. Lee KK, You JH, Wong IC, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of high-dose omeprazole

7. Hsu PI, Lai KH, Lin XZ, et al. When to discharge patients with bleeding peptic ulcers: infusion as adjuvant therapy to endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer.

a prospective study of residual risk of rebleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:160e4.

1996;44:382e7. 36. Khuroo MS, Yattoo GN, Javid G, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and placebo for

8. Cipoletta L, Bianco MA, Rotondano G, et al. Outpatient management for low-risk bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1054e8.

non-variceal upper GI bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 37. Jang J, Dong S, Jung J, et al. High-dose oral proton pump inhibitor is as effective as

2002;55:1e5. intravenous administration in the aspect of increasing pH and reducing rebleeding

9. Brullet E, Campo R, Calvet X, et al. A randomized study of the safety of outpatient after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastroenterology

care patients with bleeding peptic ulcer treated by endoscopic injection. Gastrointest 2006;103:A467.

Endosc 2004;60:15e21. 38. Bajaj JS, Dua KS, Hanson K, et al. Prospective, randomized trial comparing effect of

10. Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Ma TK, et al. Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer oral versus intravenous pantoprazole on rebleeding after nonvariceal upper

bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol gastrointestinal bleeding: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52:2190e4.

2010;105:84e9. 39. Javid G, Masoodi I, Zargar SA, et al. Omeprazole as adjuvant therapy to endoscopic

11. Lau JY, Leung WK, Wu JC, et al. Omeprazole before endoscopy in patients with combination therapy for treating bleeding peptic ulcer. Am J Med 2001;111:280e4.

gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1631e40. 40. Kaviani MJ, Hashemi MR, Kazemifar AR, et al. Effect of oral omeprazole in reducing

12. Sreedharan A, Martin J, Leontiadis G, et al. Does proton pump inhibitor (PPI) re-bleeding in bleeding peptic ulcers: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, clinical

treatment initiated before endoscopy work in unselected upper gastrointestinal trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:211e16.

bleeding? A Cochrane systematic review update. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 41. Laine L, McQuaid KR. Endoscopic therapy for bleeding ulcers: an evidence-based

(7):CD005415. approach based on meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol

13. Tsoi KK, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of high-dose omeprazole Hepatol 2009;7:33e47.

infusion before endoscopy for patients with upper-GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 42. Wang CH, Ma MHM, Chou HC, et al. High-dose vs non-high-dose proton pump

2008;67:1056e63. inhibitors after endoscopic treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer:

14. Lin H, Wang K, Perng CL, et al. Early or delayed endoscopy for patients with peptic a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern

ulcer bleeding: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol Med 2010;170:751e8.

1996;22:267e71. 43. Calvet X, Barkun A, Bardou M, et al. High-dose vs non-high-dose PPIs after

15. Lee JG, Turnipseed S, Romano PS, et al. Endoscopy-based triage significantly endoscopic treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: current evidence is

reduces hospitalization rate and costs of treating upper GI bleeding: a randomized insufficient to claim equivalence. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1698e9 author reply

controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:755e61. 1700.

16. Bjorkman DJ, Zaman A, Fennerty MB, et al. Urgent vs elective endoscopy for acute 44. Choi KD, Kim N, Jang IJ, et al. Optimal dose of intravenous pantoprazole in patients

non-variceal upper GI bleeding: an effectiveness study. Gastrointest Endosc with peptic ulcer bleeding requiring endoscopic hemostasis in Korea. J Gastroenterol

2004;60:1e8. Hepatol 2009;24:1617e24.

17. Tsoi KK, Ma TK, Sung JJ. Endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: how urgent 45. Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lam YH, et al. Endoscopic retreatment compared with surgery in

is it? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:463e9. patients with recurrent bleeding after initial endoscopic control of bleeding ulcers.

18. Shaheen AA, Kaplan GG, Myers RP. Weekend versus weekday admission and N Engl J Med 1999;340:751e6.

mortality from gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by peptic ulcer disease. 46. Loffroy R, Guiu B, D’Athis P, et al. Arterial embolotherapy for endoscopically

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:303e10. unmanageable acute gastroduodenal hemorrhage: predictors of early rebleeding.

19. Dorn SD, Shah ND, Berg BP, et al. Effect of weekend admission on gastrointestinal Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:515e23.

outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:1658e66. 47. Ripoll C, Banares R, Beceiro I, et al. Comparison of transcatheter arterial

20. Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K. Outcomes of weekend admissions embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic

for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a nationwide analysis. Clin Gastroenterol treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15:447e50.

Hepatol 2009;7:296e302. 48. Wong TC, Chiu PW, Wong KT, et al. A comparison of transcatheter arterial

21. Tsoi KK, Pang SH, Chiu PW, et al. The risk of ulcer-related death in relation to embolisation to surgery after failed endoscopic hemostasis to bleeding peptic ulcers.

hospital admission on public holidays: a cohort study on 10,428 cases of upper Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:AB113e14.

gastrointestinal bleeding in Hong Kong. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:AB141. 49. Chan FK, Hung LC, Suen BY, et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac and omeprazole in

22. Sung JJ, Chan FK, Lau JY, et al. The effect of endoscopic therapy in patients reducing the risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients with arthritis. N Engl J Med

receiving omeprazole for bleeding ulcers with nonbleeding visible vessels or adherent 2002;347:2104e10.

clots: a randomized comparison. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:237e43. 50. Chan FK, Wong VW, Suen BY, et al. Combination of a cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor

23. Lau JY, Chung SC, Leung JW, et al. The evolution of stigmata of hemorrhage and a proton-pump inhibitor for prevention of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients at

in bleeding peptic ulcers: a sequential endoscopic study. Endoscopy very high risk: a double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet 2007;369:1621e6.

1998;30:513e18. 51. Lai KC, Chu KM, Hui WM, et al. Celecoxib compared with lansoprazole and naproxen

24. Sung JJ, Barkun A, Kuipers EJ, et al; Peptic Ulcer Bleed Study Group. Intravenous to prevent gastrointestinal ulcer complications. Am J Med 2005;118:1271e8.

esomeprazole for prevention of recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. 52. Spertus JA, Kettelkamp R, Vance C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of

Ann Intern Med 2009;150:455e64. premature discontinuation of thienopyridine therapy after drug-eluting stent

25. Jensen DM, Ahlbom H, Eklund S, et al. Rebleeding risk for oozing peptic ulcer placement: results from the PREMIER registry. Circulation 2006;113:2803e9.

bleeding (PUB) in a large international studyda reassessment based upon 53. Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic

a multivariate analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:AB117. ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:1e9.

26. Kahi CJ, Jensen DM, Sung JJ, et al. Endoscopic therapy versus medical therapy for 54. CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomized, blinded trial of clopidogrel versus

bleeding peptic ulcer with adherent clot: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events. Lancet 1996;348:1329e39.

2005;129:855e62. 55. Chan FK, Ching JY, Hung LC, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin and esomeprazole to

27. Laine L. Systematic review of endoscopic therapy for ulcers with clots: can prevent recurrent ulcer bleeding. N Engl J Med 2005;352:238e44.

a meta-analysis be misleading. Gastroenterology 2005;129:2127. 56. Lai KC, Chu KM, Hui WM, et al. Esomeprazole with aspirin versus clopidogrel for

28. Saeed ZA, Cole RA, Ramirez FC, et al. Endoscopic retreatment after successful initial prevention of recurrent gastrointestinal ulcer complications. Clin Gastroenterol

hemostasis prevents ulcer rebleeding: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy Hepatol 2006;4:860e5.

1996;28:288e94. 57. Weil J, Colin-Jones D, Langman M, et al. Prophylactic aspirin and risk of peptic ulcer

29. Tsoi KK, Chiu PW, Sung JJ. Endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: is routine bleeding. BMJ 1995;310:827e30.

second look necessary? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:717e22. 58. Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and

30. Chiu P, Choi C, Kwong K-H, et al. The effect of scheduled second endoscopy against aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary

intravenous high dose omeprazole infusion as an adjunct to therapeutic endoscopy in intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001;358:527e33.

prevention of peptic ulcer rebleedingda prospective randomized study. 59. Yun KH, Rhee SJ, Park HY, et al. Effect of omeprazole on the antiplatelet activity of

Gastroenterology 2006;130:A121. clopidogrel. Int Heart J 2010;51:13e16.

1176 Gut 2011;60:1170e1177. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Guidelines

60. Sibbing D, Morath T, Stegherr J, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors 65. Huang CC, Chen YC, Leu HB, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes in Taiwan associated

on the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel. Thromb Haemost with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors in patients who

2009;101:714e19. received percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1705e9.

61. Neubauer H, Engelhardt A, Kruger JC, et al. Pantoprazole does not influence the 66. O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and

antiplatelet activity of clopidogrelda whole blood aggregometry study after coronary clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor:

stenting. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2010;56:91e7. an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet 2009;374:989e97.

62. Gaglia MA Jr, Torguson R, Hanna N, et al. Relation of proton pump inhibitor use 67. Ray WA, Murray KT, Griffin MR, et al. Outcomes with concurrent use of clopidogrel

after percutaneous conronary intervention with drug-eluting stents to outcomes. and proton-pump inhibitors: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:337e45.

Am J Cardiol 2010;105:833e8. 68. Kwok CS, Loke YK. Meta-analysis: the effects of proton pump inhibitors on

63. Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, et al. A population-based study of the drug cardiovascular events and mortality in patients receiving clopidogrel.

interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:810e23.

2009;180:713e18. 69. de Aquino Lima JP, Brophy JM. Conflicting evidence: what’s a clinician to do?

64. Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with Ann Intern Med 2010;153:413e15.

concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary 70. Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in

syndrome. JAMA 2009;301:937e44. coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1909e17.

Editor’s quiz: GI snapshot

Gut September 2011 Vol 60 No 9 1177

Downloaded from http://gut.bmj.com/ on February 19, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com

Asia-Pacific Working Group consensus on

non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Joseph J Y Sung, Francis K L Chan, Minhu Chen, Jessica Y L Ching, K Y

Ho, Udom Kachintorn, Nayoung Kim, James Y W Lau, Jayaram Menon,

Abdul Aziz Rani, Nageshwar Reddy, Jose Sollano, Kentaro Sugano,

Kelvin K F Tsoi, Chun Ying Wu, Neville Yeomans, Namish Vakil and K L

Goh

Gut2011 60: 1170-1177 originally published online April 6, 2011

doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.230292

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://gut.bmj.com/content/60/9/1170

These include:

References This article cites 68 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

http://gut.bmj.com/content/60/9/1170#ref-list-1

Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

service box at the top right corner of the online article.

ErrataAn erratum has been published regarding this article. Please see next

page or:

/content/60/10/1444.3.full.pdf

Topic Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections

Collections Ulcer (484)

Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli (242)

Helicobacter pylori (218)

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

PostScript

< Additional materials are published online only. To view (SNPs), tagging the two haplotype blocks Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK; 6Department of Paediatric

these files please visit the journal online (http://gut.bmj. encoding ICOSLG as well as the region Gastroenterology, Royal Hospital for Sick Children,

com). extending to rs762421 (which achieved Yorkhill, Glasgow, UK; 7Department of Paediatric

a genome-wide significance in the CD meta- Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Royal

Competing interests None. Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, UK

analysis by Barrett et al).5 Detailed pheno-

Ethics approval This study was conducted with the

typic characteristics of this cohort have been Correspondence to Paul Henderson, Department of

approval of the MREC South West.

previously described.6 SNPs were selected Child Life and Health, University of Edinburgh, 20 Sylvan

Contributors Dr Julie Parkes on behalf of the authors. using HapMap data based on solid spine of Place, Edinburgh EH9 1UW, UK;

linkage disequilibrium and minor allelic paul.henderson2@nhs.net

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; not

externally peer reviewed. frequency >0.1, thus tagging haplotypes Funding Staff salaries and consumables were

with a frequency >5%. A detailed single supported by a Medical Research Council patient

Published Online First 11 February 2011 research cohort initiative grant G0800675 for PICTS (the

marker and haplotype analysis by trans-

Gut 2011;60:1443e1444. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.235838 mission disequilibrium testing (ParenTDT) Paediatric-onset IBD Cohort and Treatment Study) to

was carried out using Haploview (v 4.2) with Dr Wilson.

REFERENCES robust permutation analysis (n¼100 000). Competing interests None.

1. Tsochatzis EA, Manousou P, Fede G, et al. Validating The two-marker haplotypes (rs762421A/

non-invasive markers of fibrosis: the need for a new Ethics approval This study was conducted with the

Gers8126734A/G and rs283529G/ approval of the Lothian REC/2002/6/18 (August 2002),

histological reference standard. Gut 2011;60:1442e3.

2. Parkes J, Roderick P, Harris S, et al. Enhanced liver Cers4818890C/A, both located within the 39 renewed in 2006 as ongoing.

fibrosis (ELF) test can predict clinical outcomes in patients untranslated region (UTR) of ICOSLG)

showed weak associations with overall IBD Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; not

with chronic liver disease. Gut 2010;59:1245e51.

externally peer reviewed.

3. Rosenberg WM, Voelker M, Thiel R, et al. Serum susceptibility (single marker and haplotype

markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort analysis: p<0.05) which did not retain signifi- Published Online First 18 February 2011

study. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1704e13. cance after permutation analysis. However, Gut 2011;60:1444. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.235325

the strength of this association increased

Variation in ICOSLG influences substantially when we focused our analysis on REFERENCES

childhood-onset CD. After stringent permu- 1. Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, et al. Genome-

Crohn’s disease susceptibility tation analysis, the rs8126734A allele showed wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of

a significant overtransmission to affected CD confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat

Recent genome-wide association studies have Genet 2010;42:1118e25.

identified more than 70 loci which confer patients (p¼0.02, OR 1.81 (95% CI 1.26 to

2. Imielinski M, Baldassano RN, Griffiths A, et al.

susceptibility to Crohn’s disease (CD).1 2.58)) with D9 and r2 for rs762421 having

Common variants at five new loci associated with

However, the critical coding regions within values of 0.78 and 0.21, respectively. The two- early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet

most of these loci are largely unidentified and marker haplotype consisting of rs762421A 2009;41:1335e40.

it is therefore important that further work is and rs8126734G also showed a significant 3. Coquerelle C, Oldenhove G, Acolty V, et al. Anti-

carried out to robustly identify the candidate distortion of transmission (p¼0.03). Using CTLA-4 treatment induces IL-10-producing ICOS+

genes to guide future deep sequencing a sliding two-marker haplotype analysis to regulatory T cells displaying IDO-dependent anti-

assess the extent of the CD association signal inflammatory properties in a mouse model of colitis.

studies. A locus on chromosome 21q22

harbouring several genes including inducible from the 39 UTR to the 59 end of the ICOSLG Gut 2009;58:1363e73.

coding sequence (rs2970558G/C is located in 4. Sato T, Kanai T, Watanabe M, et al. Hyperexpression

T cell costimulator (ICOSLG), autoimmune of inducible costimulator and its contribution on lamina

regulator (AIRE) and periodic tryptophan intron 3), we found that association signals do

propria T cells in inflammatory bowel disease.

protein 2 homologue (PWP2) has been shown not extend upstream from rs8126734, thus Gastroenterology 2004;126:829e39.

to influence susceptibility to both adult and implicating the 39 interval between rs762421 5. Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, et al. Genome-wide

paediatric CD and ulcerative colitis (UC).1 2 and rs8126734 as a target region for deep association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility

The protein encoded by ICOSLG is inti- sequencing. loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet 2008;40:955e62.

mately involved in the proliferation and We have applied the first family-based 6. Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, et al.

association analysis of ICOSLG in childhood- Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-

differentiation of T lymphocytes (through

onset CD, thus minimising the effect of onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology

binding with inducible T-cell costimulator 2008;135:1114e22.

(ICOS)), especially with regard to the balance population stratification. We demonstrated

between regulatory and Th17 subsets. that the signal at the 21q22 locus is most

We read with interest the paper by likely to be due to germline variation at the 39 CORRECTIONS

Coquerelle et al3 in GUTwhich demonstrated end of ICOSLG. Therefore, our analysis

makes it less likely for non-synonymous doi:10.1136/gut.2010.232918corr1

that the treatment of trinitrobenzene

sulfonic acid-induced murine colitis was ICOSLG SNPs or other genes in the region

(such as PWP2 or AIRE) to contribute signif-

Macho Fernandez E, Valenti V, Rockel C,

ameliorated by anti-CTLA-4 antibodies et al. Anti-inflammatory capacity of selected

through the induction of ICOShigh T regula- icantly to inherited CD susceptibility. Deep

sequencing of the 39 UTR of the ICOSLG gene lactobacilli in experimental colitis is driven

tory cells. This and other work have

is now warranted to identify causative vari- by NOD2-mediated recognition of a specific

suggested a role for the ICOSeICOSLG

interaction in CD pathogenesis.4 ants, potentially affecting mRNA stability. peptidoglycan-derived muropeptide. Gut

We therefore used a gene-wide haplotype- 2011;60:1050e9. The surname of the first

Paul Henderson,1,2 Johan van Limbergen,1,3,4 author should be Macho Fernandez, and not

tagging approach to assess the strength of

Niall H Anderson,5 Elaine R Nimmo,2

association across the ICOSLG gene and to Fernandez alone.

Richard K Russell,6 Jack Satsangi,2

delineate the region of strongest association David C Wilson1,7

with childhood-onset CD to further assess doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230292corr1

1

whether it has a role as a potential CD Department of Child Life and Health, University of

Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK; 2Gastrointestinal Unit, Centre Sung JJY, Chan FKL, Chen M, et al. Asia-

candidate gene. A total of 416 patients aged

for Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Pacific Working Group consensus on non-

below 17 years diagnosed with inflammatory Edinburgh, UK; 3Department of Paediatric

bowel disease (IBD) within Scotland (278 variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Hospital for

CD, 101 UC and 37 IBD-unclassified) and 735 Sick Children, Toronto, Canada; 4Department of Gut 2011;60:1170e7. Dr Chun Ying Wu’s

parents (276 complete trios) were genotyped Immunology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; affiliation should be Asia-Pacific Working

5

for four single nucleotide polymorphisms Centre for Population Health Sciences, University of Group, Taiwan.

1444 Gut October 2011 Vol 60 No 10

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Natural History of Vasa Previa Across Gestation Using A Screening ProtocolDocument7 pagesNatural History of Vasa Previa Across Gestation Using A Screening ProtocolwijePas encore d'évaluation

- Pi Is 0849583116304554Document7 pagesPi Is 0849583116304554wijePas encore d'évaluation

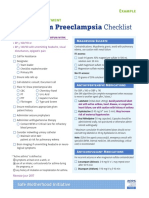

- Postpartum Preeclampsia Checklist: Emergency Department ExampleDocument1 pagePostpartum Preeclampsia Checklist: Emergency Department ExamplewijePas encore d'évaluation

- AnnMedHealthSciRes MAcrosomiaDocument6 pagesAnnMedHealthSciRes MAcrosomiawijePas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Akut Abdomen PDFDocument8 pagesJurnal Akut Abdomen PDFwijePas encore d'évaluation

- Good18.Prenatally Diagnosed Vasa Previa A.30Document9 pagesGood18.Prenatally Diagnosed Vasa Previa A.30wije0% (1)

- v1 Ref Status: Indexed, Http://f1000r.es/2f8Document5 pagesv1 Ref Status: Indexed, Http://f1000r.es/2f8wijePas encore d'évaluation

- VASA Previa CaseDocument3 pagesVASA Previa CasewijePas encore d'évaluation

- Case Vasa PreviaDocument1 pageCase Vasa PreviawijePas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Mitchell H. Katz-Evaluating Clinical and Public Health Interventions - A Practical Guide To Study Design and Statistics (2010)Document176 pagesMitchell H. Katz-Evaluating Clinical and Public Health Interventions - A Practical Guide To Study Design and Statistics (2010)Lakshmi SethPas encore d'évaluation

- Interventions For Preventing Falls in People After Stroke (Review)Document68 pagesInterventions For Preventing Falls in People After Stroke (Review)Abdelrhman AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Do School Bags Cause Back Pain?Document6 pagesDo School Bags Cause Back Pain?TPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Improves Muscle Strength Biomechanicsof Movementand Functional MobilityDocument19 pagesNeuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Improves Muscle Strength Biomechanicsof Movementand Functional MobilityAmr Mohamed GalalPas encore d'évaluation

- Grammar As A Tool For Learning LiteracyDocument52 pagesGrammar As A Tool For Learning Literacy刘艳丽Pas encore d'évaluation

- How To Read A Paper - Critical AppraisalDocument48 pagesHow To Read A Paper - Critical AppraisalMark KerrPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence-Based Treatments For Conduct Disorders - A Systematic RevDocument40 pagesEvidence-Based Treatments For Conduct Disorders - A Systematic Revrmconvidhya sri2015100% (1)

- Gastric Lavage - Position Statement 2013Document7 pagesGastric Lavage - Position Statement 2013UrgenciasCol FoamPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Pharmacist Role in ADRDocument7 pagesClinical Pharmacist Role in ADRArif Ali RphPas encore d'évaluation

- Better Medicine, Better Treatment, Better Health (DR Purnamawati SP SpAK MMPaed)Document69 pagesBetter Medicine, Better Treatment, Better Health (DR Purnamawati SP SpAK MMPaed)Ivan Danusaputra100% (1)

- Breastfeeding and The Risk of Dental Caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument23 pagesBreastfeeding and The Risk of Dental Caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisSusi susiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lee Et Al-2015-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument39 pagesLee Et Al-2015-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsRashid HussainPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug Literature Assignment FINALDocument6 pagesDrug Literature Assignment FINALToqa ElmansouryPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Practices in Public AdministrationDocument8 pagesBest Practices in Public AdministrationRicky BuloPas encore d'évaluation

- Acupuncture in Psi Chia TryDocument11 pagesAcupuncture in Psi Chia TryVineeth RavindhranPas encore d'évaluation

- Randomized Controlled Multicentre Study of Albumin Replacement Therapy in Septic Shock (ARISS) : Protocol For A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument13 pagesRandomized Controlled Multicentre Study of Albumin Replacement Therapy in Septic Shock (ARISS) : Protocol For A Randomized Controlled TrialntnquynhproPas encore d'évaluation

- Shared Book Reading by Parents With Young Children PDFDocument7 pagesShared Book Reading by Parents With Young Children PDFjiyaskitchenPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Based Medicine: by Dr. Balgis Msc. CM FMDocument125 pagesEvidence Based Medicine: by Dr. Balgis Msc. CM FMPartone MoviemakerPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Anestesi Lidokain ToksisitasDocument11 pagesJurnal Anestesi Lidokain ToksisitasAlda AdeliaPas encore d'évaluation

- NeuroaidDocument11 pagesNeuroaidlindasundaPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP Refractive Error & Refractive Surgery PDFDocument104 pagesPPP Refractive Error & Refractive Surgery PDFMia NursalamahPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Cooking Classes On FoodDocument30 pagesThe Impact of Cooking Classes On FoodKathy Princess Flores LptPas encore d'évaluation

- Khaled Hasan Resume 20180729Document6 pagesKhaled Hasan Resume 20180729api-312404919Pas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Appraisal: DR A C J Hutchesson Chair of Examiners' Panel, Frcpath (Clinical Biochemistry)Document10 pagesCritical Appraisal: DR A C J Hutchesson Chair of Examiners' Panel, Frcpath (Clinical Biochemistry)monday125Pas encore d'évaluation

- Article For Summary and CritiqueDocument14 pagesArticle For Summary and CritiqueAnonymous mu66C5Pas encore d'évaluation

- OknotokDocument6 pagesOknotokBeau PhatruetaiPas encore d'évaluation