Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Historical Roots of Zen

Transféré par

davidlg20050 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

18 vues2 pagesThis file is the work of Stan Rosenthal. It has been placed here, with his kind permission, by Bill Fear. The author has asked that no hard copies, ie. Paper copies, are made. The file was originally written on a machine using CP / M and had to be converted to dos format.

Description originale:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThis file is the work of Stan Rosenthal. It has been placed here, with his kind permission, by Bill Fear. The author has asked that no hard copies, ie. Paper copies, are made. The file was originally written on a machine using CP / M and had to be converted to dos format.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

18 vues2 pagesHistorical Roots of Zen

Transféré par

davidlg2005This file is the work of Stan Rosenthal. It has been placed here, with his kind permission, by Bill Fear. The author has asked that no hard copies, ie. Paper copies, are made. The file was originally written on a machine using CP / M and had to be converted to dos format.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 2

This document can be acquired from a sub-directory coombspapers via anonymous

FTP and COOMBSQUEST gopher on the node COOMBS.ANU.EDU.AU

The document's ftp filename and the full directory path are given in the

coombspapers top level INDEX file.

Date of the document's last update/modification 03/09/93

--------------------------------------------------------

HISTORICAL ROOTS OF ZEN

original filename: zenisnot.txt

--------------------------------------------------------

This file is the work of Stan Rosenthal. It has been placed here, with his kind

permission, by Bill Fear. The author has asked that no hard copies, ie. paper

copies, are made.

Stan Rosenthal may be contacted at 44 High street, St. Davids, Pembrokeshire,

Dyfed, Wales, UK. Bill Fear may be contacted at 29 Blackweir Terrace, Cathays,

Cardiff, South Glamorgan, Wales, UK. Tel (0222) 228858 email fear@thor.cf.ac.uk.

Please use email as first method of contact, if possible. Messages can be sent

to Stan Rosenthal via the above email address - they will be forwarded on in

person by myself - B.F.

NOTE:

You may find and odd sentence or missing information every now and again in the

files. Hopefully not to frequently. This is because the files were originally

written on a machine using CP/M and had to be converted to dos format. Many of

the 5.25 disks were very old and had bad sectors - thus missing info.

...............................Beginning of file...............................

Much has already been written of Zen from within a Buddhist context, but Zen

itself is not the prerogative of any specific religious group, even though in

its modern form, a large proportion of its practitioners are drawn from

followers of the Buddha, Guatarma Siddhartha. Historically of course, Zen

probably owes its major debt to its Buddhist practitioners for their

systemization of its concepts, and even more than this, it must be remembered

that the founder, or first codefier of Zen, The Boddhidharma, was also the

twenty-eighth Buddhist patriarch in direct teaching descent from the Buddha

himself.

However, in any serious discussion of Zen, we must also recall that something

relating to the development of Zen did occur during the four hundred years prior

to 526 CE, when the Boddhidharma arrived in the Shao-lin Temple in the Hohan

Province of Northern China, to codefy Zen practice during his prolonged

meditation, now know as 'the nine years before the wall'. What occurred during

the four hundred year period preceding the arrival of the Boddhidharma in China

was that following the establishment of Shao-lin as a major, and possibly the

first, Buddhist Temple in China in 100 CE, there was a considerable dialogue

between the Buddhist monks who inhabited the temple, and many of the people who

were indiginous to the area, and who called themselves Taoists; a fact which is

hardly surprising considering that the temple was previously a Taoist retreat.

At this point, it will probably help to clarify a number of issues if we

understand that even by 100 CE there has developed two forms of Taoism, the

earliest Tao-chia, being philosophical Taoism based upon Yin Yang theory as

explained in the esoteric theory of 'changes' ('I Ching') and in the later work,

'the Way of Virtue' ('Tao Te Ching') by the philosopher Lao Tzu who lived

towards the end of the Period of the Warring States (c 600 BCE). The later form

of Taoism known as Tao-chiao, although based upon its philosophical precedessor,

was practiced as a religion rather than a philosophy, and made considerable use

of both shamanistic and mystical religious practices, bordering on the occult,

and by 100 CE the followers of religious Taoism far outnumbered the

philosophical Taoists.

It is probable that by the beginning of the Christian era in the West, the

philosophical Taoists had lost their influence, and continued their work only in

remote regions, far from the large cities and seats of government. We know with

certainty that by this time religious Taoism held considerable influence in what

was, by now, the Chinese kingdom or empire. It was to the remote provinces that

the remaining followers of philosophical Taoism had travelled, and so it

probably was that it was in such areas as these that the dislohur between

Mahayana Buddhism and Taoist Philospphy began. It was the Buddhist monks,

practising the compassion for which many Buddhist sects are stil reknowned, who

gave succour to the 'exiled' Taoist philosphers, who in turn shared their

knowledge with their Buddhist benefactors.

So it is that it is now believed that on his arrival at Shao-lin, the

Boddhidharma found something quite foreign to the Indian practice of Buddhism,

strange but not alien. It was to prove to be the Boddhidharma's undertaking to

codify the synergized practices he discovered, but even scant knowledge of the

life of the Buddha himself provides a clue as to why the philosophy of Taoism

would not have been completely foreign to the Boddhidharma, and would certainly

not have been unknown to the Buddha himself.

It is well documented that the Prince, Guattama Siddhartha, spent many years as

a peripatetic seeker prior to his enlightenment, and many of his conversations

with 'wise men' are described in detail. Since trade had taken place between

China and India for many hundreds of years before the birth of the Buddha, trade

routes were of course well established, and it is more than likely that young

seeker would have used such routes, not only as a means of travel, but also in

order to meet with strangers to his own land. As it the case even today, much

can be learned about foreign ideas, philosophies and customs through trading in

artifacts, and many goods are decorated with the symbols indiginous to their

place of origin. With such a brilliant intellect as we know Guttama Siddhartha

possessed, it is indeed unlikely that he would not have learned of 'Yin Yang'

theory, upon which Taoist philosophy is based. Zen Buddhist scholars themselves

acknowledge many instances in which Buddhist ideas are concommitant with those

of Taoist philosophy, but there will probably always be an element of

disagreement regarding which school of thought borrowed most from the other.

All this is not to deny the Buddhist element in any form of Zen, but only to

illustrate that Zen is not wholly Buddhist, nor wholly Taoist. For many Zen

practitioners there is indeed no dichotomy, nor any need for distinction. But

it is only fair to all concerned to point out that to many non-Zen Buddhists

even Zen Buddhism is a heresy and to state that many Buddhists belonging to non

Zen sects, time and energy spent in Zen practice is considered to be of little

or no significance. For their own part, many Zen practitioners consider their

orthodox Buddhist bretheren to be 'brothers in spirit', but are disapproving

towards the hierarchical rigor with which their more orthodox brothers consider

the Buddhist deities, and with which the orthodox Buddhist institutions are

organized.

I am fully aware that I have not described what Zen is, but have hopefully

illustrated that whatever it is, it is not orthodox, not essentially a religion,

and not specifically Indian. It is possibly necessary to provide one more

negation, and this is that contrary to much public opinion in the Europe and the

USA, Zen is most certainly not Japanese in origin.

.................................End of file...................................

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Alvar Aalto 1Document4 pagesAlvar Aalto 1Santiago Martínez GómezPas encore d'évaluation

- Suburban Homes Construction Project Case StudyDocument5 pagesSuburban Homes Construction Project Case StudySaurabh PuthranPas encore d'évaluation

- International MBA Exchanges Fact Sheet 2022-23Document4 pagesInternational MBA Exchanges Fact Sheet 2022-23pnkPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL W11 MilDocument4 pagesDLL W11 MilRICKELY BANTAPas encore d'évaluation

- Asd Literacy Strategies With ColorDocument48 pagesAsd Literacy Strategies With ColorJCI ANTIPOLOPas encore d'évaluation

- PHED 111 HealthDocument19 pagesPHED 111 HealthApril Ann HortilanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Textbox 1 1 1Document3 pagesTextbox 1 1 1api-200842148Pas encore d'évaluation

- FS 1 Module NewDocument64 pagesFS 1 Module Newtkm.panizaPas encore d'évaluation

- 620 001 Econ Thought Syllabus Fall08 Wisman PDFDocument4 pages620 001 Econ Thought Syllabus Fall08 Wisman PDFJeff KrusePas encore d'évaluation

- Scholarships For Indian MuslimsDocument10 pagesScholarships For Indian MuslimsAamir Qutub AligPas encore d'évaluation

- Cot2 DLL - 2023Document3 pagesCot2 DLL - 2023Haidi Lopez100% (1)

- JK Saini ResumeDocument3 pagesJK Saini ResumePrateek KansalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effectiveness of Strategic Human ResourceDocument12 pagesThe Effectiveness of Strategic Human ResourceMohamed HamodaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid-Term Examination Card of First Semester of 2016/2017Document1 pageMid-Term Examination Card of First Semester of 2016/2017Keperawatan14Pas encore d'évaluation

- Somil Yadav CV FinalDocument3 pagesSomil Yadav CV FinalSomil YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- ResumeDocument2 pagesResumeapi-497060945Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cot FinalDocument5 pagesCot FinalFrennyPatriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning What is LearningDocument27 pagesLearning What is LearningShankerPas encore d'évaluation

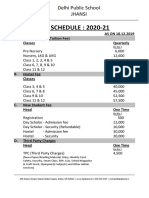

- Fee Shedule 2020-21 Final DiosDocument2 pagesFee Shedule 2020-21 Final Diosapi-210356903Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dbatu MisDocument1 pageDbatu Misgamingaao75Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mechanical CADD CourseDocument8 pagesMechanical CADD CourseCadd CentrePas encore d'évaluation

- Michel Foucault - Poder - Conocimiento y Prescripciones EpistemológicasDocument69 pagesMichel Foucault - Poder - Conocimiento y Prescripciones EpistemológicasMarce FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Seminar ReportDocument42 pagesSeminar Reportsammuel john100% (1)

- The Australian Curriculum: Science Overview for Years 1-2Document14 pagesThe Australian Curriculum: Science Overview for Years 1-2Josiel Nasc'mentoPas encore d'évaluation

- Evan Kegler: 5280 Coquina Key DR SE, St. Petersburg, FL Ekegler@law - Stetson.edu - 352-422-1396Document1 pageEvan Kegler: 5280 Coquina Key DR SE, St. Petersburg, FL Ekegler@law - Stetson.edu - 352-422-1396api-306719857Pas encore d'évaluation

- HCMC Uni English 2 SyllabusDocument13 pagesHCMC Uni English 2 SyllabusNguyen Thi Nha QuynhPas encore d'évaluation

- Public VersionDocument170 pagesPublic Versionvalber8Pas encore d'évaluation

- MSU Political Science Student Officers Request Library ClearanceDocument1 pageMSU Political Science Student Officers Request Library ClearanceKirsten Rose Boque ConconPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Phase 1 - Terminology of Language TeachingDocument4 pagesActivity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Phase 1 - Terminology of Language TeachingMaria Paula PeñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Intro. To Philo. Q2 (Module2)Document8 pagesIntro. To Philo. Q2 (Module2)Bernie P. RamaylaPas encore d'évaluation