Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

CURTIS. Commodities and Sexual Subjuctivites

Transféré par

Mónica OgandoCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CURTIS. Commodities and Sexual Subjuctivites

Transféré par

Mónica OgandoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Commodities and Sexual Subjectivities: A Look at Capitalism and Its Desires

Author(s): Debra Curtis

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Feb., 2004), pp. 95-121

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3651528 .

Accessed: 06/01/2013 15:31

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Cultural Anthropology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Commodities and Sexual Subjectivities:

A Look at Capitalism and Its Desires

Debra Curtis

Salve Regina University

Imagine Tupperware-style sex toy parties held for working- and middle-class

women: bank tellers, kindergartenteachers, waitresses, and nurses.' As guests

arrive, conversations are innocuous enough: day-care issues, dessert recipes,

and home decorating tips. Before the evening ends, they will have been intro-

duced to a varietyof products,from scentedmassage oils to anal beads and cuffs.

Much of the anthropological literature on sexuality, although ethnog-

raphically rich in its description of community building and sexual cultures,

fails to attend to the complex processes by which sexual subjectivity is pro-

duced (Hostetler and Herdt 1998). This article examines the production of sex-

ual subjectivity as it is articulatedwithin the sex-toy industry, a specific aspect

of consumer culture that appearsto address it most directly. My point of depar-

ture is that the marketplaceproduces desires, thus encouraging sexual innova-

tion; however, it is importantto note that the proliferation of sexual difference

does not arise uncontested.2Contemporarysocial theorists have argued that the

market economy thrives on difference and is dependent on the production of

desire (Giddens 1991; Laqueur1992; B. Turner1984). I want to ask: How might

the desire produced in the marketbe intricately linked to the formation and ne-

gotiation of sexual subjectivity? Does the apparentplurality of the market evi-

dent in an arrayof consumer choices produce a proliferation of multiple sexu-

alities? Put simply, this article considers the relationship among commodities,

consuming desires, and sexual practices.3

It is assumed here that sexuality is produced and mediated by culturally

specific historical and social processes. This social constructionist framework

rejects the idea that purely biological models can explain sexuality. A number

of social theorists (Butler 1993; Foucault 1978; Herdt 1981, 1987; Lancaster

1992; Parker 1991; Sedgwick 1990; Weeks 1977), in their effort to understand

how sex is constructed across time and space, have long recognized the advan-

tages of denaturalizingsexuality by deconstructingthe links between sexual prac-

tice, desire, and sexual identity.The ethnographicrecord(see, for example, Herdt

1981, 1987; Lancaster 1992; Morris 1994) demonstrates how categories such

as "homosexual"and "heterosexual"fail to account for the ways that different

CulturalAnthropology 19(1):95-121. Copyright ? 2004, American Anthropological Association.

95

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

96 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

cultures make sense of sexual practices or assign meanings to them. For in-

stance, one of the many reasons why homosexual or heterosexual categories do

not work empirically and analytically is because sexual practice does not al-

ways follow sexual identity. Moreover, sexual practice is not always driven by

sexual desire, and sexual desires may exceed an individual's sexual practice.

This conceptual frameworkraises complex questions about the relationship be-

tween sexuality, sexual practice, and sexual desire, which, I would argue can

only be understood within a specific cultural context.

By invoking "subjectivity,"I am writing against the notion of sexual iden-

tity, which posits a unified and coherent sexual subject. Sexual subjectivity, to

borrow from Sally Alexander, "is best understood as a process which is always

in the making, is never finished or complete" (1994:278). By emphasizing the

constitutive process-how sexual subjectivity is produced-we can attend to

the ways individuals attemptto construct their sexual lives within dynamic and

particularsocial structures.

Tupperware-Style Sex-Toy Parties: A Brief Description

It is late and I am looking for a side street in Warren,Rhode Island. I drive

past the local pharmacy and the veterans' home on my way to a one-story, sin-

gle-family home. As I approachthe front door, I notice that the interior of the

house is almost dark with candles lighting the living room. The hostess, a

young woman in her early twenties, greets me. She thinks I work for the sex-

toy distributing company, Athena's Home Novelties. "The helper's here," she

shouts to the other women gathered in the kitchen. There is some commotion in

one of the back rooms where a heavy-set woman dressed in sweatpants and an

oversized sweatshirt is on the phone giving directions to Jennifer, Athena's ex-

ecutive director and the company's most popular home sex-toy demonstrator.

From what I can discern from the phone conversation, Jennifer is lost some-

where in Warren driving a Winnebago stocked with sex toys. The woman on

the phone instructsJennifer to pull into the parking lot of the American Touris-

ter luggage store. "My daughterand I will come get you; we'll be there in five

minutes." The mother and daughter collect their coats and head for the door.

Meanwhile Wendy, the hostess, is at the counter, busy adding more Bacardi

rum to the fruit punch. She is obviously nervous, exclaiming, "The leader is

late! This kind of thing could only happen at my party." Her guests, mostly

young white women in their twenties, try to distract her. A young blond in a

New England Patriots' T-shirt comments on how well the new carpets coordi-

nate with the trim on the walls. "You must have paid close to $500 for these

rugs at Sears, didn't you?" pries anotherguest. Wendy, having put three scoops

of peach sherbet into the punch as a final touch, lifts the heavy crystal bowl and

carefully carries it to the table. Another guest arrives, a middle-aged woman

who is Wendy's stepmotherMarge. She announces that this is one of two home

demonstration shows she is attending this week. Tomorrow night, she tells us,

she will be attending a candle demonstration show. As Marge approaches the

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 97

punch bowl, I hear her say to no one in particular,"I can't believe I came to one

of these things."

Soon Wendy announces with relief, "We can get started now, Jennifer is

here." By now 20 women, all of whom are white, have gathered in the TV

room. Jennifer walks in carrying a large box, followed by the mother and

daughter who had gone off to meet her. They too are carrying boxes. Later in

the evening, I learn that the mother and daughterare both named Dawn.

Jennifer, visibly pregnant and dressed in a tailored suit and matching

pumps, puts her box down in the corner of the room and quickly turns to greet

the guests, thanking them for their patience. She turns to me and asks, "Are

you the anthropologist? Are you Debra?" Recognizing some of the women in

the room from other parties, Jennifer says, "I'm sorry I don't have anything

new for you tonight. But I just returned from Vegas, where I attended a big

sex-toy convention. I'll have new products by January."

Jennifer explains to the group of women gathered in the TV room that she

startedselling sex toys as a way to supplement income from her day job at a lo-

cal drugstore. The first year she earned $13,000. Five years ago, she started

Athena's Home Novelties, which is based in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. It is

currentlythe largest sex-toy distributorin the region and the sixth largest in the

United States. This year Athena's has grossed $3 million. The company's pri-

mary means of advertising is word of mouth. Although Jennifer employs over

200 distributors, she remains the most popular and most frequently sought-af-

ter party leader and must be booked a year in advance.

Before Jennifer begins the formal demonstration, she carefully unpacks

the contents of the three large boxes. She takes out an assortmentof creams, lo-

tions, candles, and bath soaps and arranges them neatly on a small table. The

last box, the largest of the three, contains an array of vibrators, dildos, videos,

and a harness.

The guests crowd into the room. I sit on the plush tan sectional couch next

to Wendy's mother and stepmother while others sit on the floor and stand in

the doorway. Jennifer begins the demonstration with a carefully crafted

speech, stating that 80 percent of women fake orgasms and find sex unfulfill-

ing. She charismatically describes how a satisfying sexual relationship can im-

prove one's quality of life. As part of her sales pitch she reminds women that

society's message about sex, particularly as it relates to females, is that "good

girls" are not supposed to desire sex or enjoy it. Athena's mission, according to

Jennifer, is to "destroy this absurd and discriminatory myth." She passes

aroundan aromatherapycandle "laced with human pheromones"to arouse sex-

ual desire. Next, the guests are introducedto pheromone cologne, which we are

all instructed to "test" on our wrists and necks. As part of the demonstration,

guests learn about Ben Wa Balls, which if used regularly can help with inconti-

nence as well as improve vaginal elasticity and sexual sensations. Nipple Nib-

blers, the Duo Pleasure Ring, and a variety of toys including the Silver Bullet,

the White Wolf, the Ultimate Beaver, and anal beads are passed around the

room for closer inspection.

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Jennifer's performanceis commanding. She describes in great detail how

each product is used as well as its benefits. Her explanations are enriched with

comical one-liners. As she holds up a pair of vibrating black leather panties,

she explains how your partnercan control the remote and activate the panties

from afar. "Imagine,"Jennifer says, "ChristmasEve at your in-laws' will never

be the same." Party guests are just as entertaining. At one point in the evening

an erotic video entitled "The Dinner Party"is passed around the room. The fe-

males featured on the cover are large breasted, wearing only high heels and

elaborate jewelry. They are standing front to back, pressing their bodies to-

gether. As the video circulates aroundthe room, Jennifer describes how this is

the most "tastefully" crafted erotic video she's seen. Just then, the mother of

the hostess is handed the video. She apparentlyhas missed Jennifer's explana-

tion. She loudly exclaims, "Oooh, what's this?" Her daughter explains,

"Mother,it's pornography.You know, a dirty movie." Holding the video close,

the mother responds, "Well, I didn't think it was Little Women."

Throughoutthe demonstrationguests are encouraged to keep a "wish list"

on the back of the Athena catalog, noting the products that are most appealing

to them. After an hour, Jennifer invites the guests to line up for their individual

shopping opportunity in the Winnebago parked outside. The room quickly

clears with the exception of a few who remain to tidy up, including Dawn and

Dawn, and Wendy's stepmotherMarge. Earlierin the evening when Marge and

I had moved from the kitchen to the TV room she told me that she would only

be buying gifts for her stepdaughter.As she walked around, picking up empty

plastic cups and small paper dessert plates, she informed me, without reserva-

tion, that she is definitely buying toys for herself tonight.

After I introduce myself to the mother and daughter, I learned they are

veterans of the sex-toy party scene. Mother Dawn proudly informs me that she

has attended over six and that she was the first to host a party. Her daughter,

when asked why the parties were such a success, explained, "It's Jennifer. She

makes you feel so comfortable .... We're taught that sex is something dirty,

something to be ashamed of.... She gives it a whole new meaning.... She's

professional . . . she's funny ... she describes things we can all relate to." Ex-

citedly another woman exclaims, "She's great! ... She's even been on the

Howard Stern show. Or maybe it was the Jerry Springer show, I can't remem-

ber." Turning back to the daughter Dawn, I timidly ask her if she is satisfied

with the merchandise she has purchasedin the past at other parties. Her mother

interruptsus to tell me that she has procured all of the Silver Bullet products

including the Double Bullet. It becomes difficult to focus my attention as both

mother and daughterare talking over each other. The daughterhas nothing but

positive things to say about the Silver Bullet, a three-inch multipurpose vibrat-

ing egg. Leaning toward me, Dawn describes how two of her girlfriends used

the Silver Bullet while driving home after the party she had thrown. We walk

out a side door. It is chilly and dark. Most of the guests are lined up waiting for

their turnin the Winnebago. The door of the large camper opens and one of the

party guests cautiously climbs down the stairs clutching her brown paper bag

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 99

in one hand and her purse and a plastic cup in the other. She says goodbye to

the hostess. No one makes inquiries as to what she has just purchased, nor do

they attempt to peek inside her bag. I watch as she walks down the driveway.

She pauses to rummage throughher purse for her car keys, and then a few min-

utes later, she drives away. My ethnographic curiosity is piqued. Others are

lined up, still waiting their turn, some smoking, some leafing through the

Athena catalog, privately and not-so privately, making last minute selections.

By the end of the evening, 13 guests buy over $1,000 worth of products and

Wendy, the young hostess, is awarded $100 worth of free gifts.

Capitalism and Its Desires

Theorizing the link between consumer culture and sexuality is particularly

important in view of the fact that consumption has become so central to cul-

tural production in capitalist societies. Suggesting that consumer culture is a

site for the production of identities is nothing new. The literatureis full of im-

pressionistic assertions that consumption is central to identity production

(Clark 1991; D'Emilio 1993; Friedman 1990; Hennessy 2000; Rutherford

1990; T. Turner 1993). However, the anthropological literaturethat looks em-

pirically at the relationship between consumption, desire, and sexual practice

is sparse.4This is not to say that anthropologists are neglecting how sexual sys-

tems and practices are conditioned by material and political processes. On the

contrary,for example, Roger Lancasterand Micaela di Leonardo stress the im-

portance of understanding how political economy shapes sexual meanings,

practices, and desires. For example: Are sexual practices and sexual cultures

inherently matters of political and economic interests? What is the link be-

tween sexual cultures and material production and consumption? A political-

economic interpretationof sexuality, according to them, is one that "neitherre-

duces sexual expression to a consequence of 'material life' . . . nor imagines

that human sexual and reproductive lives can be considered apart from the

changing political economies in which those lives are embedded (1997:4).

For my purposes I turn to several studies that begin to substantiate the

linkages between the market, desire, and sexuality. Thomas Laqueur (1992)

provides a wonderful reading of sexual desire and the market economy in the

context of the industrial revolution. Building on Hume, Marx, and Malthus,

Laqueur asserts that the market economy is dependent on the proliferation of

desire. He argues, "factories, cities, shops, markets, novels, and medical tracts

were themselves engines of desire" (1992:185). In a critique of capitalism,

Gilles Deleuze and F6lix Guattari(1983) stress the prolific nature of desire as

free-floating, autonomous, and abundant.It is reconfigured as productive and

generative, rather than lacking and limited. What we gain from these ap-

proaches is the opportunity to view desire as central to an analysis of capital-

ism and a dislocation of desire from the biological and private domain, so that

instead we begin to see desire as "both generated and deployed by social prac-

tices" (Laqueur1992:185). John D'Emilio addressesthe conditions of capitalism

in the early 20th century that gave rise to gay communities and subcultures.

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

100 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

He asks, "What are the relationships between the free labor system of capital-

ism and homosexuality" (1993:468)? Here he looks at employment issues, mi-

gration to urban centers, the increase of individual capital accumulation, the

creation of social spaces for homosexuality, the ideological changes toward

homosexuality, and the reconfiguration of the family under capitalism, to sup-

port his connection between material conditions and the "making of gayness."

D'Emilio's research supports the notion that capitalism thrives on social plu-

ralism. His study also suggests that capitalism not only produces the prolifera-

tion of desires but that it requires legitimation of these new desires (see also B.

Turner 1984:29). Most importantly perhaps is Haug's (1986) analysis of the

aesthetics of commodities in late capitalism. Inspired by Marx, Haug looks at

how commodities become eroticized objects, and in turn, how human sexuality

is molded and restructuredby capitalism. Mockingly, Haug writes: "sexual en-

joyment becomes the commodity's most popular attire" (1986:56). Desire is

produced through the sexualization of commodities, tapping into the con-

sumer's fancies, appetites, and needs. Moreover, "what is being thrustupon the

public is a whole complex of sexual perception, appearance, and experience"

(1986:56). According to Haug, sexuality is used by the advertising industry to

transformcommodities, to increase their appearanceof use-value, and to create

mass appeal and greater exchange value. "Thus," writes Haug, "commodities

borrow their aesthetic language from human courtship; but then the relation-

ship is reversed and people borrow their aesthetic expression from the world of

the commodity" (1986:19).

It is the latter part of Haug's configuration that I want to focus on. How

does commodity consumption shape sexuality, or in other words, how do com-

modities produce desires that shape and/or change the available scripts for sex-

ual practice? The concept of sexual scripts was introduced by William Simon

and John Gagnon (1986) and refers to how individuals reproduce and recog-

nize a repertoire of sexual acts, as well as a set of rules and expectations sur-

rounding those acts. Moreover, the concept of sexual scripts also allows re-

searchers to investigate how individuals, in turn, shape and/or reproduce

notions of sexuality within a culture. For instance, Hostetler and Herdt refer to

the way in which the pornography industry has affected the sexual scripts

available to gay men in that consumers were "offered a wider range of sexual

activities, including sadomasochism (SM), fisting, and various 'fetishes' "

(1998:271).

These disparate but overlapping studies are relevant in understandingthe

complex interaction between commodity consumption, desire, and sexual

practice because they emphasize that desire is both social and productive as

well as constituted within social fields, such as the market in this instance. The

idea that desire is socially produced forces a number of interesting questions,

for example: Are we able to theorize the nature of desire independent of a spe-

cific social context?"Positing desire as social assumes that desire is not innate,

immutable,or a priori.This however does not occlude the individual's subjective

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 101

experience of desire. On the contrary, this project intends to chart how desire,

which is fashioned by the market,in turn shapes sexual practice.

Along these lines, I am interested in pursuing Rubin's (1984) position

where she argues against a critique of capitalism, or more precisely, she takes a

position that opposes those who see the commercialization of sexuality in a

wholly negative light. This enables me to ask: What are the positive effects of

the market economy in terms of sexuality? This question invariably raises two

important methodological issues for the anthropologist. First, can we empiri-

cally assess the effects that the market has on sexual desires, practices, and

subjectivities? Second, can the consumer narrateher own incitement?

In days that followed the party, I attempted to elicit responses from par-

ticipants about the ways in which desire was manufacturedduring the demon-

stration by asking each individual to explain how and why certain products ap-

pealed to them. Narrating one's own incitement proves to be challenging, as

one of my interviewees noted: "I don't think people will be able to tell you

what comes over them ... but something happens.... Take for instance my

stepmother. She told me that she had no intention of buying anything for her-

self... I don't know what came over her, but she spent $50" (Wendy, age 24).

Rita (age 30) responded: "I have been into sex shops before, and half the time

you don't have a clue what you're looking at. But after Jennifer describes the

product, you think to yourself, 'I've gotta have that, I've just gotta have that.'

Plus, if you think that a certain toy will make your orgasms more intense, more

pleasurable, then who wouldn't want to buy it?" Another interviewee named

Nancy (age 43) exclaimed: "Ijust have to think about my 'Silver Bullet' and I

get excited."

Nancy's comment illustrates how, to borrow from Parker and Gagnon,

"the experience of desiring things may be isomorphic with desiring sexual ex-

perience" (1995:13). I was hoping, however, that the participants' responses

would reveal more about the production of desire in the context of the home-

based demonstrationshows. What is affirmed is that desire is dependent on the

symbolic associations consumers attach to sex toys, particularly during the

demonstration. I realized early on that it became important to understandthe

process of symbolic signification. Attempting to elicit the participants' expla-

nations as to how and why their interests were stimulated proved to be unpro-

ductive. When dealing with the affective domain, it is more productive to un-

cover the participants' impressions of the sex toys as a way to interpret how

desire is produced. In this particular context, the toys become "meaningful"

through Jennifer's performance. Participants consistently remarked on this

process, albeit indirectly: "It's Jennifer. She gives sex a whole new meaning."

Several participants made the following comments repeatedly: "She's profes-

sional and well educated," and "She's normal, not like a stripper .... She's

someone I could be friends with.... She's wholesome and natural.... She re-

ally knows her stuff. .. . She's done a lot of research."Adhering to a structural-

ist interpretationof how goods acquire social meaning, Judith Williamson ar-

gues that meaning is transferredto a commodity, in this case a dildo, a vibrator,

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

102 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

a penis ring, or a set of cuffs, from an intermediaryobject that in turn links the

commodity to what Williamson calls a "referent system" (1986:106). In this

case, the intermediary objects are the professional, well-coiffed distributors

from Athena's. The products merge with the personality attributesthat partici-

pants have assigned to the distributors.The toys, however, are never divested

of their "old" meanings. The commodities simultaneously represent conflict-

ing abstract qualities, wholesomeness, well being, and fun, on one hand, and

reckless abandon and uncontrollable passion, on the other. Jill (age 40) who

describes herself as prudish, explained: "I always thought sex toys were dirty.

I've never, ever bought anything like this in my life. Believe me! But she made

them sound so fun and harmless but yet still illicit." The signification of the

sex toys is produced on multiple semantic fields, allowing for a continual shift-

ing of meaning that perpetuates and sustains desire. As "wholesome" as Jen-

nifer portrayedthe cock ring and vibrator to be, for instance, consuming such

products is still about realizing "forbidden"and unmentionable desires.

In marketing the toys, Athena's distributorshave perfected the process of

borrowing from the language of human courtship, so that in turn the commodi-

ties appearto promise more than "good sex" but romance, too. As explained by

Beth (age 38), who has been married for 11 years and describes herself as

"middle class and heterosexual (at least to date)": "As much as the parties are

portrayedas X-rated, I felt like they were selling monogamy, commitment, and

loyalty.... The accessories are about intimacy.... You bought the stuff be-

cause you felt like your relationship would be better."Along similar lines, Jane

(age 24), who has been involved with the same partnerfor eight years, com-

ments: "WhenJennifer described how Good Head [a mint gel used for oral sex]

would feel, I wanted this productbecause I knew my partnerwould love it!"

Often the Athena distributors share their own sexual experiences as part

of the demonstration, for instance, casually commenting on how much their

partners"loved" a certain toy. As skilled marketers,they rely on promoting the

"intangiblecharacteristicsof the product"(Rago 1989:10) to establish an emo-

tional bond between not only the product and the consumer but, more impor-

tantly, between themselves and the consumer. In the process of creating this

emotional bond, the marketer sanctions a liberal attitude about sex-an atti-

tude that also suggests the possibility for new ways of experiencing pleasure.

This camaraderie,coupled with romantic and sexual promise, insinuates itself

into the consumer's aspirations and sexual-subjectivity.

Obviously the marketing performance is not the sole force stimulating

guests to purchase goods. I came to understand, after attending a dozen or so

parties, that consumption and desire within this ethnographic context are

closely tied to sociality. Not only is consumption "eminently social" (Ap-

padurai 1986:31), but also desire, although dependent on biological structures,

is socially manufactured.6Desire, to borrow from Roger Lancaster, "exists not

within us but between us" (1992:270), as one of my informants attests:

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM

ANDITS DESIRES103

It has mademy sex life better!It's not the sameold routinethatwe've beendoing

for the past 26 years.... WhenI got married26 years ago, I would neverhave

boughttheproductsI havenow.AndI wouldhaveneverdiscussedsex thingswith

anyone,especiallyat a partywith my daughter.... But these partiesgive you so

manyideas-ideas thatneveroccurredto me-and thenyou findoutthateveryone

is lookingfor ideasandwe all havethe sameneeds. [Dawn(age 46)]

Here Dawn hints at the way in which desire becomes a "social ratherthan

an individual phenomenon" (Parkerand Gagnon 1995:13). Several researchers

(e.g., Parker and Gagnon 1995; Stoler 1997; Rubin and Butler 1994; Vance

1984) have suggested that more work should be done to investigate the social

processes by which desire is produced and consumed. As Stoler writes: "We

have looked more to the regulation and release of desire than to its manufac-

ture" (1997:28). What comes to mind at this point is Rubin's understandingof

the domain of the erotic. In an interview with Judith Butler, Rubin stresses the

need for greater understanding of the political economies of erotic significa-

tion (Rubin and Butler 1994:79). In other words, for Rubin, the theoretical

question becomes "What are the historical and social contexts which shape

erotic meanings?"This line of inquiry speaks to the ways in which erotic signi-

fication is contingent and shifting.7 For example, within the sexual value sys-

tem that Rubin uses to describe popular sexual ideology, the use of sex toys,

fetish objects, and pornography is considered "abnormal,""unnatural,"and

"bad"(Rubin 1984:281). Once seen as a marginalized practice assigned exclu-

sively to certain subgroups, the use of sex toys is moving into mainstreamcul-

ture and shaping public desires.8Consequently, the seemingly private desires I

was trying to understandwere inherently social desires. Moreover, the desire

to consume the products for their imagined sexual promise, is both socially

produced and sanctioned by the group of females gathered at the demonstration

parties. The groups assembled at sex-toy parties, albeit in relation to larger

economic and cultural conditions, manufacturedesires that recognize and le-

gitimate alternative repertoires of sexual acts promised by the commodities.

Parties were peppered with confessions and personal testimonials as new items

were displayed. Veterans of the sex-toy party scene offered their opinions and

judgments on the utility and effectiveness of certain items. Some parties more

than others seem to be more conducive to sexual revelation and personal state-

ment. This is largely dependent on the age of the guests, their familiarity with

each other, as well as the presence and use of alcohol, as evidenced by this

brief description of anotherparty.

"Girls Just Wanna Have Fun"

Just past the New Bedford police station, I turn right on the main road for

Park Homes, a large housing project. When I arrive, a young woman in her

early twenties meets me at the screen door. Three young women, Danielle,

Tina, and Emerald, are hosting this party in Danielle's apartmentwhere she

lives with her two small children. The apartmentis small and furnished with a

ripped faux-leather couch, some metal chairs, a large 28-inch television, and a

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

104 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

state-of-the-artboom box. The program Direct Effect, which counts down the

top five hip-hop videos, is playing on MTV. Before long, the small living room

is full of young women, mostly black and Hispanic. Bottles of Bacardi rum, te-

quila, gin, and Sprite accompany a plastic bowl filled with Doritos on a small

wooden coffee table. Some of the guests start doing shots. Tina, a young and

very big Hispanic woman, dressed in a white low-cut blouse and a long black

skirt with a revealing slit up the side, yells to Danielle to bring her some salt

from the kitchen. Danielle appears with a large container of salt, the other

guests laugh, teasing Danielle because she does not own salt and pepper shak-

ers. When Danielle reappearsshe is carrying a tray of green and yellow Jell-O

shots. Beth, a white woman who works as an Athena distributorjoins us in the

living room. The women are excited and engrossed in doing shots of tequila.

Soon the room gets quiet enough for Beth to describe what she calls her

"warm-up game." She opens a large plastic toolbox and takes out a large

spongy yellow vibrating ball. "The object of the game," Beth announces, "is to

pass the ball around the room without using your hands. If the ball makes it

successfully around the room without touching the floor, each of the three

hostesses will receive a five-dollar gift certificate in addition to the credit they

earn by your purchases."Emerald roars, "Well if I'm going to be necking with

another chick, I'd better have myself another shot." All three of the hostesses

cheer as the vibrating ball makes its way back to Beth. Realizing that most of

the guests are veterans of the sex-toy party scene, Beth asks if the group is just

interested in hearing about the new products. "Oh no," Emerald shouts, "We

want the whole show." Beth struggles to begin. The guests are rowdy and it is

difficult to hold the group's attention. She passes around several scented can-

dles and bath oils. Anxious to get their attention, she takes out a product called

Cleopatra's Secret and describes how it is an ointment that, when rubbed on a

woman's clitoris, will heighten and increase sensitivity. She asks for a volun-

teer from the group. Danielle and Diana encourage Tina. Willingly, Tina

stands and approaches Beth who instructs Tina to take a small amount of oint-

ment and apply it in the bathroom. The other guests are roaring with laughter.

Tina emerges from the bathroom, with a somewhat puzzled, but concentrated

look on her face, "It's not working," she reports. "Did you put it on right?"Em-

erald asks. "Did you put it on your clit?" "I know where my clit is, you fool!"

Tina shouts back. As Beth explains each new item, some of the guests chime in

offering their opinions; others counter Beth's claims. Time and time again,

guests shout out, "Oh you've gotta have that!"Before Beth wraps up her pres-

entation, she asks for one last volunteer. The group volunteers Danielle. Stand-

ing up, Danielle is asked to put on a pair of black leather panties over her blue

jeans. Beth gives Emerald the remote that controls the vibrating panties. All of

the guests are focused now on Danielle's face. Disappointed, Danielle claims

not to feel the effect of the battery operated vibrating panties. Beth assures her

that it must be the denim jeans she's wearing. Once Beth finishes and all of the

products are returnedto the toolbox, she announces that she will be taking one

guest at a time in the kitchen. At this time the room gets very quiet while all of

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 105

the women focus on making their final selections in the catalog. The room

stays quiet for about ten minutes. When a police siren sounds outside, no one

looks up.

Consuming Desires and Producing Sexualities

What exactly is Athena's selling to these women from diverse class and

ethnic backgrounds? Its distributors rely on images and narratives that repre-

sent wholesomeness and naturalness, combined with novel forms of pleasure.

Clearly the distributors are peddling sexual enjoyment and fantasies. In order

to do this, they capitalize on the participants' fantasies as well as produce new

ones for consumption while converting them into profit. What are the partici-

pants purchasing? Is it sex? Better sex? Confirmation of desirability? Or are

participants, as Haug might cynically assert, trying to satisfy "unfulfilled as-

pects of their existence" (1986:56)?

Critics of advertising and consumer culture maintain that marketing

strategies are designed to create the very needs that they then propose to satisfy

and that ultimately are left unsatisfied (Galbraith 1976). For members of the

FrankfurtSchool, consumer culture produces passivity, as well as individuals

who are no longer able to recognize "real" needs (Horkheimer and Adorno

1994). This line of argument assumes that we can distinguish between real

needs and the needs and desires that are produced by the market (Shaw 1996;

B. Turner 1984). The question then becomes whether we are able to "distin-

guish between genuine and artificial wants, and why should the latter be

thought less important"(Shaw 1996:371)-particularly if, as anthropologists,

we recognize that all human needs and wants are socially produced.

I returnnow to one of my original questions proposed at the beginning of

the article. How is desire linked to the formation and negotiation of sexual sub-

jectivity? I am using subjectivity here in a late Foucauldian sense-the notion

of the subject as constituted by practice (Foucault 1987) and less as an effect of

power and disciplinary technologies (Foucault 1977, 1978). This notion of the

self, which appears in The Use of Pleasure (1987) and The Care of the Self

(1988), is a corrective to Foucault's earlier work, which rejects the interior do-

main. Stuart Hall characterizes Foucault's move, which he made toward the

end of his career, as one that produces a "discursive phenomenology of the

subject" (1996:14), a subject that is capable of "recognition and reflection"

(1996:13). I combine this idea with Hostetler and Herdt's (1998) notion of sub-

jectivity, which is the "sense of personal efficacy ... that emerges from the in-

terstices of culturally patternedways" (1998:276). For some, this might be far

too reminiscent of the humanist subject-capable of producing effects and in-

tended results. For me, a "sense of efficacy" is not the same as self-determina-

tion; rather,the notion of efficacy allows for the ways in which subjects delib-

erately practice self-production(Hall 1996:13). Consumptionpractices become

some of the means by which individuals construct their own lives. Appadurai's

comments are certainly appropriatehere in the context of consumption and

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

106 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

sex-toy parties: "Wherethere is consumption there is pleasure, and where there

is pleasure there is agency" (1996:7).

So how is desire linked to the formation and negotiation of sexual subjec-

tivity? Does desire, which drives consumption, eventuate in the proliferation

of sexualities? By consuming these sex toys, are participants creating new

scripts for themselves? In other words, are participants buying goods that in

turn change the way they think about themselves as well as alter their sexual

practices? Is it possible that, for its participants, commodity consumption be-

comes one of the primarymeans for demonstratingtheir sexuality? Wendy, the

hostess who attended two parties prior to hosting one herself, maintains that

her willingness to "trynew things" was reinforced by new notions of pleasure.

In other words, despite conventional wisdom, the commodity kept its prom-

ise!9 In describing the Duo Pleasure Ring (a silicone penis ring with space for

attaching a small vibrator), Wendy strongly asserts: "Once you've had this

kind of pleasure, you want more. It's addicting." Another of my interviewees,

Jill, relates: "When I first used my Pearl Rabbit I had to turn the thing off be-

cause the feeling was so, so, so ... [begins to laugh aloud] ... My legs were

shaking.... If more women used these, they wouldn't need antidepressants."

Another, named Cindy, responds: "What are you asking me? If I buy these

things does it change the way I see myself, my sexual identity?I don't know ... I

am more sexual. I desire sex more often and I have sex more than I ever have.

Is that what you mean?" Frances, who has had the same sexual partnerfor 20

years, explains:

Yes, of course buying these toys changedmy sex life. Look, I'm almost40. I

thoughtI knewwhata goodorgasmwas all about-but this is different.Thisis in-

tense and incrediblylong lasting.I meanintense... in the past my husbandand

me spenta lot of timejust gettingreadyfor sex. You know-trying to get in the

mood.WhenI use the SilverBullet,it takesme thirtysecondsto get in the mood

andI spendthe restof the timeenjoyingdeep,deeporgasms.

Without a doubt, Frances values pleasure but she also seems to place some

importance on efficiency. Note that Frances reports that it takes thirty seconds

to "get in the mood" and that orgasm follows soon thereafter. The emphasis

here is on the Silver Bullet's potential to produce the desired effect in the

shortest amount of time possible with minimal effort. Conventional wisdom,

which circulates and is reproduced in popular culture, clearly maintains that

women enjoy and appreciate a slower pace. If this is the case, where does the

notion of efficient sexual subjectivity come from? Frances is not the only par-

ticipant to remarkon how the commodities produced a model of efficient sexu-

ality. Is how fast one can "cum"a function of capitalist discipline? Frances of-

fers an example of how the self internalizes the technologies of capitalism and

how time is considered a productive potential to be fully realized, an aspect of

capitalismthatFoucaultelaboratelydiscusses in PartII of Discipline and Punish.

This notion of efficiency comes up again with Noreen (age 20), who felt

that she needed to procure the most expensive commodity "to get the job

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 107

done," so to speak. Although Athena's requires guests to be 18 years old,

Noreen has been attending parties since she was seventeen. In the past three

years she has been to six parties. Comparedwith the majority of my informants

for whom the use of sex toys is a novel practice, Noreen's sexuality has been

substantially shaped by the consumption and use of these commodities. By this

I mean her notions of sexual pleasure, the sex acts she engages in, and her ideas

about what is erotic have been formed by the acquisition of these toys:

WhenI went to my first party,I was floored.I'd neverseen anythinglike that.I

was sexuallyactivethen,butI'd neverhadan orgasm.I didn'tbuy anythingat the

firstpartyI wentto, butthenI wentto anotherpartyandboughta PearlRabbit.It

cost $100, butI thought,becauseit did more,thatI shouldget it. I hadmy firstor-

gasm with it. WhenI had my own party,I invited 14 friends;they spent$100 a

piece. I got $140 to use as credit.

During one of our discussions, I asked Noreen if the demonstration shows

or the sex toys gave her new ideas for her sex life. She responded, "No, not re-

ally, because how can anything be new if I only have ever used the toys?"

While reflecting on her sexuality, Noreen commented on the fact that when she

first started attending the home-based demonstration shows, she was very

naive and inexperienced; in her own words, she said, "I had no idea what I was

doing." Noreen's statements unmistakably reveal the ways in which her sexu-

ality is shaped by her consumption practices.

In my attempt to theorize the relationship between the production of de-

sire and sexual subjectivity, I have been circling aroundthe concept of fetish-

ism. Culturalcritics have used the concept of fetish as deployed by both Freud

and Marx, to understandhow individuals come to desire objects or things. It

became clear to me early on that my informants developed strong erotic attach-

ments to their sex toys. For instance, a number of my informants made it

known to me that they kept back-up toys in case their favorites malfunctioned.

It was also not uncommon for veterans of the home-based sex-toy party scene

to offer advice during the demonstrationswhen various items were on display.

"You gotta have that!" was a common refrain at parties. Many of my inform-

ants, especially those for whom the use of sex toys has become a regular fea-

ture in their sexual repertoire,fetishize the sex toys. This was particularlycom-

mon among women who described using the Pearl Rabbit, which is considered

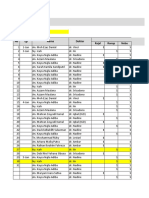

the "Cadillac of vibrators"(see Figure 1). The Pearl Rabbit is a seven-inch bat-

tery operated vibratorwith a section of pearls at the base of a rotating shaft de-

signed to stimulate the "G-spot." There is a three-inch appendage (a rabbit's

head with ears) attached to the shaft at a 45-degree angle. The vibrating rabbit

ears encase the clitoris for stimulation. In fact, one of my informants expressed

concern that she had become so attached to her Pearl Rabbit that it had dis-

ruptedher sexual relationship with her husband.

The idea of fetishism as used by both Marx and Freud is predicated on the

assumption that there are "natural"versus "unnatural"needs. Consequently,

this implies thatcertainobjects of desire aremore legitimatethanothers.Invoking

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

108 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

siP

Figure 1

Pearl Rabbit.

fetishism requires that we break free from this legacy. To reiterate:cultural an-

thropologists have long argued that human needs, desires, and wants are so-

cially mediated. Indeed the ethnographic data provided here might create a

space in which we can begin to construct a theory of sexuality based on fet-

ishes-a move that Teresa de Lauretis (1992) suggests might be productive. A

focus on fetishism draws attention to a number of theoretical issues concerned

with the social construction of sexuality. A theory of sexuality built aroundfet-

ishism spotlights the process of erotic signification that allows us to explore

the contingent natureof the erotic as well as the social and economic structures

shaping it. A focus on fetishism also encourages us to look at the flux and vari-

ability of desire, what Vance calls the "fluidity of sexual desire" (1984:9). In

other words, the concept of fetishism contributes to our understandingof how

individual notions of the erotic change. Lastly, organizing sexuality around

fetishism would resist cataloguing the varieties of sexual practices around sex-

ual identities.

If, for the sake of clarity, we define sexual subjectivity as sexual practice

and desire, then yes, without a doubt my informants report that their consump-

tion practices have changed-sometimes moderately, sometimes radically-

their sexual subjectivities. Some women who identify as "heterosexual" and

are involved with male partnerstalk about "using" lesbian scenes depicted in

the videos to "get off." A small number of women involved in heterosexual

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 109

relationships described using vibratorson their male partners.It is not that any

of these desires or practices are new in the history of sexuality, so to speak, it is

that this particular aspect of consumer culture arouses and produces new

forms of sexualityfor the individuals involved. The sex-toy parties serve as ve-

hicles for an arrayof sexual scripts. The scripts generated by the commodities

become resources for self-imagining and self-production. This became evident

when several individuals describe having sex with their partnerswhile watch-

ing erotic videos. One informantexplains it this way:

It's not thatwe copy the sex scenesas we watchthemunfoldon TV. ... No, it's a

combinationof things .... I imaginemyself in the scene ... the video images

themselvesincreasemy pleasure... andI knowmy partneris turnedon watching

otherpeoplehavesex. It's a bunchof thingshappeningat once. ... Plus,you also

get to see peopleusing sex toys in the videos.

Ethnographically speaking, the parties provide an interesting forum for

exploring the intersection of consumption, imagination, and sexual subjectiv-

ity. What I heard over and over again from my informants is that these home-

based demonstration shows provided them with new ideas in a forum that was

palatable to their "moral"sensibilities. Repeatedly, guests would tell me that

on arriving at the parties they had no intention of buying the products. But be-

cause the one-hour demonstrations were so "informative" and so "tasteful,"

and because the distributorsappeared "wholesome" and "trustworthy"-char-

acteristics that my informants, regardless of their ethnicity, class, and age fre-

quently assigned to the distributors-my informants came to identify with the

female distributors. This identification process facilitated consumption: the

guests purchased goods that they had previously regarded as taboo. Not only

were they purchasing goods that they once regardedas off-limits, but the dem-

onstration shows generated novel sexual scripts promoting diverse sexual ac-

tivities, some of which many guests could never have imagined. For instance,

here is a comment by Maria (age 40): "I'd never heard of butt-plugs. Have

you? I didn't buy them this time, but I have a girlfriend who did.... She uses

them with her husband. She says that you slip them in before you have an or-

gasm. Who would have thought?" Here is another example of how certain

commodities produce newly imaginable sexual possibilities: "I think of myself

as straight. I do think about having sex with women-a lot, especially when I

see those videos-but I'm not gay .... I think there's a difference."

The success of Athena's marketingis predicatedon the distributors' abili-

ties to appeal to the erotic differences within a seemingly homogeneous group.

For example, for some women, the purchase of a sex toy or an adult video is in-

spired by previous fantasies or desires and Athena's distributors successfully

tap into this, but for other women, new fantasies are produced within the con-

text of the home-based demonstration shows. That some of the women had

never conceived of using sex toys or fantasized about them should not come as

a surprise.It demonstratesthe variabilityand range of sexual knowledge, or more

specifically, it demonstrates how some individuals have had limited exposure

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

110 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

to adult novelty products. One of my informantsrecalls a time when in a public

park she tripped over what she now is able to identify as a double-dildo. Prior

to her exposure to the goods presented at the sex-toy party, she had never en-

countered sex toys, and as such, certain items were beyond her cultural refer-

ence and sexual knowledge base.

Another issue for a number of my informants is the accessibility of sex

toys, which is not unrelated to access and exposure to sexual knowledge. Sev-

eral informants, who purchased a vibrator for the first time through Athena's,

expressed that they had wanted to try sex toys in the past but refused to patron-

ize adult book stores (popular sites for the sale of sex toys) and could not imag-

ine asking for assistance from a retail clerk. Antonia, for example, related:

I would nevergo into a pornstore or a XXX video place.... Those places are

sleazy with sleazymeninsideandbadlighting.Placeslike thatdon't inspireyou.

... I thinkit's the party.... I learnednew information,like the fact I could use

small vibratorsfor anal simulationon my boyfriend.... I neverknew that....

Plus the partyis pleasurable.Andyou knowhow womenlike to talk.Theylike to

knowwhatotherpeoplethinkandwhatotherpeoplearedoing.

What happens in these one-hour demonstration shows is that consump-

tion, to paraphraseColin Campbell (1995), is motivated by the pleasure that

the guests derive from the "self-illusory experiences" that they produce from

the associations attached to the sex toys. The link between imagination, con-

sumption, and sexual subjectivity is about the creation of new possibilities-

some are acted on, others not. Sexual practice informs sexual subjectivity, but

so does desire, and many times there is no necessary correspondence between

desire and practice, just as anthropology and queer studies have shown us that

there is no necessary correspondencebetween sexual practice and sexual iden-

tity (Herdt 1981, 1987; Lancaster 1992; Sedgwick 1990; Weeks 1977). Ana-

lytically, it can be useful to separate sexual desire from practice, but I would

also argue that desire is a form of practice. For instance, several women re-

ported that after viewing the erotic videos, they began to use lesbian sexual im-

agery to stimulate desire at times when they were alone and/or having sex with

their male partners.In these moments, sexual desire takes the form of practice

(in the sense that one does something when one fantasizes).

What does it mean for individuals to rely on commodities for the produc-

tion of sexual self-expression? Critics often devalue this form of self-expres-

sion and self-cultivation. For instance, Giddens, while not explicitly comment-

ing on sexual practices, asserts that commodification and consumption are

central to the production of identities and lifestyles in late capitalism. Markets,

dependent on expansion, have the dual tasks of "standardizingconsumption

patterns" and promoting "freedom of individual choice" (1991:197). When

combined with the methods used by advertisers to carve out marketniches, this

results in, accordingto Giddens, a productionof the self that becomes akin to the

"possession of desired goods and the pursuitof artificiallyframed styles of life"

(1991:198). In other words, the pursuit of self-identification is synonymous

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 111

with consumption. Thus far the model is satisfactory. The problem, however,

lies with the way Giddens asserts that this process is a "substitutefor the genu-

ine development of self' (1991:198). Furthermore,despite Giddens's willing-

ness to see that individuals can "reactcreatively," consumption is devalued and

renderednarcissistic.

Along similar lines, Allison (1994), in her ethnographyof masculinity in a

Japanese hostess club, argues that in a money economy, identities and subjec-

tivities are determined by and through consumption practices. She reminds us

that Marx first commented on the commodification of identity. Allison sug-

gests that according to Marx, "it is as consumers ratherthan producers . .. that

we come to differentiate and identify who and what we are" (1994:193). The

"pitfalls"to this, according to Allison, are twofold. First, given that as consum-

ers we are subject to the continuous production of new desires and needs in the

market,we are "never totally or ultimately satisfied." Second, "looking to con-

firm and satisfy ourselves in the things that we buy, we buy more and more, yet

the satisfaction and confirmation of the self we are seeking constantly eludes

us" (1994:194). In her recent study on gender and sexuality in Japanese popu-

lar culture, Allison, borrowing from social models generated by Frankfurt

School theorists, provides a lengthy description of the consumer sexual cul-

ture. Linking together sexuality, desire, and the logic of the market, Allison

writes:

Desirestimulatesbuying... [however]only whenit remainsperpetuallydeferred.

... [Moreover]sexualitymustbe dangledin frontof consumersin sucha waythat

it promisesan excitementthatcan neverbe fully realized;thatis, to commodify

sexualityrequiresthatit be shapedintoa formthatis bothcapableof excitingand

unableto definitivelysatisfy.[2000:154]

Does Allison's notion of the elusivity of the consumer self coupled with the

idea of deferred satisfaction accurately represent the participantsof the sex toy

parties and what they are experiencing? And what about Giddens's description

of the consumer as narcissistic? Is this an accurate portrayal?

Daniel Miller's insights serve as a corrective to Giddens's model. He con-

tends, "desire for goods is not assumed to be natural, nor goods per se either

positive or negative" (1995:157). Moreover, the lack of desire for goods is not

necessarily about the preservation of the authentic "self." Miller holds that

reading commoditization as "either destructive or liberating" (1995:147), or

narcissistic for that matter, prevents anthropologists from understanding the

significance of consumption for the people we work with. So what can we say

about Allison's argumentthat the consumer "self' remains persistently elusive

so that confirmation of the consumer self is unattainable?Allison's model is

problematic because the production of the self becomes synonymous with con-

sumption, with the exclusion of all other social and political processes. The

same can be said about Giddens's model. While the focus of this project is on

sexual subjectivityand consumerculture,I see self-productionor self-constitution

as linked to myriad social contexts and relationships. So, although Allison's

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

112 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

description of the consumer "self' might accurately capture a "structure of

feeling" that pervades consumer culture, I doubt that it represents the full ex-

tent of the ways in which my informantscome to recognize themselves.

The notion that the "projectof the self' in late capitalism is always medi-

ated and dominated by consumption and commodification fails in its under-

standing of the "self"'as constituted in multiple contexts. With this in mind, we

need to ask: What is the process by which these multiple affiliations and social

roles interact? How, for example, will Nancy, a mother of two, a practicing

Catholic, and a political conservative make sense of her use of a vibrator for

sexual fulfillment when she is alone and/or with her husband? One might

speculate that attending sex-toy parties and the consumption and use of com-

modities such as vibrators and erotic films, for instance, might be inconsistent

with other aspects of my participants' otherwise middle- and working-class

lives: going to work, raising children, attending church services. What is not

clear is whether my participantsview such practices as inconsistent with other

aspects of their lives, and if they do, whether inconsistencies will be tolerated

or made to seem less threatening than they would otherwise be or whether it

will motivate participantsto alter this or other parts of their lives. A limitation

of this study is a clear understandingof how participants fully integrate new

sexual practices with other aspects of their social lives. In fact this is exactly

what needs to be done in sexuality studies. Hostetler and Herdt in their exami-

nation of queer theory write:

Only by payingattentionto how individualsbalanceculturaldemands,political

commitments,and deeply socialized life-desires-some concordant,othersdis-

cordantwithculturalnorms-can we arriveata deeper,morecomplicatedconcep-

tualization of individual subjectivity and agency. [ 1998:261]0"

Before closing, I would like to note that throughoutthe study I became in-

creasingly aware of my informants' varying abilities to narratethe trajectories

of their sexual subjectivities. Some of the women were able to discuss their

erotic preferences or significant events that had shaped their sexual lives in

great detail; others were either unwilling or unable to offer insight into their

sexuality. This disparity among my informants compels me to query whether

all aspects of an individual's sexual subjectivity, particularly sexual fantasies,

can be understood. If we rely only on conventional anthropological methods of

data collection, such as interviewing, that privileges the "speaking subject,"we

ignore the possibility that access to the "interiordomain" is not always achiev-

able. Not having access to this interior space may be an inevitable obstacle in

sexuality research no matterhow loosely structuredand open-ended our inter-

views are crafted to be."

Interestingly, although this may impede research in sexuality, it has never

been a problem for the marketplace.Somehow the market seems to tap into our

most intimate and at times uncodified pleasures and desires. How does the

market system impose itself on the range of sexual practices and desires that

exist, both codified and uncodified, making them more accessible to groups of

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISMAND ITS DESIRES 113

individuals and thus much more possible for individuals to fulfill certain fanta-

sies? Let me elaborate. A number of informants were surprised and pleased to

learn there were products designed for anal simulation that they could use on

themselves or their male partners.How does the marketrealize this new sexual

trend-the latest market niche? Susie Bright (1997) explores aspects of this in

her discussion of the production of amateurpornography.Here she argues that

amateurproducers set new sexual trends:

Amatuervideos arethe crystalball of whatyou'll see duplicatedin morerefined

pornographyin the seasonsto come. If a certainkindof sexuallook or behavioris

successful in the amateurs, you'll see it proliferate .... Take anal sex, which has

gone frombeing a specialtyact in mainstreamX-ratedtapesto the focus of virtu-

ally every movie that is made. . . . Now amateur is tackling one of the biggest ta-

boos in old-school heterosexualporn: men bottomingto women's cocks. In

amateur, we now see men getting fucked, completely in a heterosexual context.

[1997:159-161]

The natureof this recursive relationship between the market and new sex-

ual trends remains a promising field for future research interrogatingthe logic

of capitalism, consumption practices, and sexuality. Perhaps an alternative

methodology is required of anthropologists in our effort to understand how

commodities produce sexualities, if indeed the "interiordomain" is inaccessi-

ble. Following Bright's lead, we might read products to surmise which sexuali-

ties might be produced.12

Conclusion

The sex-toy parties I have been documenting are reminiscent of two other

phenomena, namely the original Tupperwarehome-demonstration parties and

feminist consciousness-raising groups. On the surface these events seem in-

commensurable. However, on closer inspection, the Tupperwarebusiness pro-

moted domesticity as well as employment opportunitiesfor women, which was

a priority of the feminist movement of the seventies. Placing the sex-toy par-

ties within a larger context of U.S. sexual politics is helpful for understanding

this relatively new cultural practice. In many ways, the format of the sex-toy

parties is an outgrowth of both the consumer sexual culture of the sixties and

Hugh Hefner's Playboy revolution of the 1950s and 1960s. It goes without say-

ing that Playboy radically altered the then dominant regime of sexual repres-

sion and restriction (see Ehrenreich 1983). One feminist perspective, no doubt,

would read this historical period as furthering the commodification of sexual-

ity and male hegemony and promoting the objectification of the female body.

Indeed, this may represent one side of the picture-but just one. The effect of

Hefner's sexual ideology, which promoted sexual liberation, is evident in the

phenomenon of Tupperware-style sex-toy parties. I am not suggesting that we

celebrate Hefner's empire. What I am suggesting is that we acknowledge the

contradictory effects of the market. For some, Tupperware-style sex-toy par-

ties might be enforcing conformity to dominant sexual scripts. For others still,

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

114 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

these parties signal sexual freedom. And yet, although I am a proponentof sex-

ual liberalism, I am not willing to suggest that they signal sexual utopianism.

In fact, I realize that for Foucauldian devotees, the format of these parties and

my subsequent research methods might be read as facilitating the "austere

monarchy of sex" (Foucault 1978:159) and its ruses. Yet I am not convinced

that this cultural practice serves as an example of what Foucault (1978) and

Marcuse (1964), for that matter,might see as an instance when apparentsexual

liberty is actually a form of domination. By arguing this, I am not conflating

consumer choice with sexual freedom; I am merely asserting that when we

stress the liabilities of consumer culture by focusing exclusively on the ways

that pleasure is deferred and satisfaction is unattainable, we miss the moments

that contradict this-moments when consumer satisfaction and even bliss is

achieved. Additionally, in an era when Gap-style sex-toy stores may become

the norm, and when large mail-order sex toy distributors,like Xandria, employ

toy-testers to improve product marketability,it has become importantto docu-

ment the diversity of sexual experiences in the context of sexual consumer-

ism.13 There have been several significant periods in recent history in which

consumer culture has altered sexual ideologies and practices. For instance, les-

bian paperbackbooks, particularlythose authoredby Ann Bannon in the 1950s

and 1960s, serve as another example of how commodities shape and produce

sexualities. These pulp romance novels expanded the number of cultural refer-

ences for women looking for new scripts on same-sex relationships.

Lastly, I want to come back to an importantissue that I do not think can be

overstated. It is the idea of promoting a sexual morality that is democratic. I

borrow this concept from Rubin (1984) who argues persuasively that a sexual

morality rooted in a democratic foundation is premised on the principles of

equality as opposed to discrimination. "A democratic morality should judge

sexual acts by the way partnerstreat one another, the level of mutual consid-

eration, the presence or absence of coercion, and the quantity and quality of the

pleasure" (1984:283). She continues by explaining that "pluralistic sexual eth-

ics" depend on a "concept of benign sexual variation" (1984:283). Cloaked in

an admonishment, Rubin closes this discussion with a powerful reminder of

anthropology's legacy to sexuality studies and contemporary culture alike-

the idea of sexual relativity:

Progressiveswho wouldbe ashamedto displayculturalchauvinismin otherareas

routinelyexhibitit towardssexualdifferences.We havelearnedto cherishdiffer-

ent culturesas uniqueexpressionsof humaninventivenessratherthanas theinfe-

rior or disgusting habits of savages. We need a similarly anthropological

understanding of differentsexualcultures.[1984:283-284]

Granted,when Rubin penned this statement,sexuality studies was nascent.

Now the academicstudy of sex is enormousand the diversity of researchsubjects

too numerousto mention here. However, althoughthe notion that sexuality is so-

cially constructedand that sexual moralities are invented has gained a powerful

foothold in partsof the academy,these concepts are ferociously contested in other

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CAPITALISM AND ITS DESIRES 115

parts, particularly among sociobiologists (Tiger 1999; Wilson 1999). More-

over, these concepts are far from being fully embraced by the public. Although

the sexual hierarchy that Rubin (1984) uses to describe popular sexual culture

has been reconfigured over the past 15 years, I am not convinced that, outside

of queer publics and parts of the academy, we have reached an "anthropologi-

cal understandingof different sexual cultures,"nor for that mattera democratic

sexual morality.

I would like to think, in the words of Richard Rorty, that anthropologists

are still "connoisseurs of diversity ... who are expected and empowered to ex-

tend the range of society's imagination"(1991:206) for the purpose of promot-

ing a liberal democracy. The question then follows: How does an ethnography

about sex-toy parties for working- and middle-class women inspire liberalism?

It might not-except that, as Rorty reminds us, the development and expansion

of liberal ideals depends on what he calls the "specialists in particularity"

(1991:207), ethnographersand others who have the opportunity, based on the

nature of anthropological inquiries, to bring to the table incommensurable no-

tions of what are considered "good" and "normal"cultural practices and be-

liefs-in this case, sexual differences. As a pragmatist, Rorty's notion of mo-

rality is contingent, so that moral systems and principles are capable of

responding to change. For Rorty, "the formulation of general moral principles

has been less useful to the development of liberal institutions than has the grad-

ual expansion of the imagination of those in power, their gradual willingness to

use the term 'we' to include more and more different sorts of people"

(1991:207). After all this is said, however, I am reminded of one informant's

responses, which challenges me to differentiate between promoting a demo-

cratic sexual morality and a notion of sexual morality that is "witlessly rela-

tivistic":14 "We're talking about dildos and vibrators. We're not talking about

getting turned on by 'snuff films' or little kids. What's the big deal? I'm not a

pervert."

The small irony here is not lost. As I position myself, vis-a-vis my inform-

ants, as a proponent of sexual liberalism, my informant effortlessly draws the

line between herself and those whom she perceives to be her sexual Others,

namely "perverts."At this point, I remind myself that a democratic sexual mo-

rality is not about moral consensus; rather,it is more about the recognition that

erotic practice and sexual difference cannot be used as the basis for producing

social hierarchies (Rubin 1984). However, to avoid witless relativism, it is best

to follow Gayle Rubin's lead-that is to say that within a democratic sexual

morality,sexual acts shouldbe evaluatedby the presenceor absence of coercion.15

Notes

Acknowledgments.I am indebtedto LouisaScheinfor hermentorshipas well as

forherkeeninsightson variousaspectsof thisproject.RogerLancaster,a carefulreader

of this article,was generouswith comments.I would like to expressmy gratitudeto

PaulaBoulduc,JuliaBucci,ArtFrankel,JimGarman,JimHersh,Eve Sterne,andPaige

Westfortheirfeedbackandfor theintellectualcompanionship theyprovide.I also want

This content downloaded on Sun, 6 Jan 2013 15:31:25 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

116 CULTURALANTHROPOLOGY

to acknowledge Fred Errington, Deborah Gwertz, Peter Guarnaccia, Michael Moffatt,

and Bruce Robbins. Although these individuals were not directly involved in the produc-

tion of this article, I am indebted to them for their intellectual generosity. This article has

benefited greatly from Ann Anagnost's close reading and numerous suggestions. Of

course it would not have been possible had I not had the support of Jennifer Jolicoeur,

owner of Athena's Home Novelties, who invited me to join her at several home-based

parties and then later introduced me to a number of her distributors, all of whom gra-

ciously extended invitations to me to attend parties. I am grateful to all of the hostesses,

many of whom were strangerswho opened their homes to me. Finally, this article is for

Steve Butler, with immense gratitudeand affection.

1. The Tupperware-style party refers to direct marketing through home-based

demonstrationparties. In this case, it also evokes a mainstreamdomestic scene in which

sex toys have entered as welcomed objects ratherthan being marked as belonging to an

alien sexual subculture.

2. See Lancaster2003:285-347 for a discussion of the politics of sexual innovation

in the marketplace.See Clark 1991, Hennessy 2000, and Chasin 2000 for critiques of the

commodification of sexual identities. See Storr2002 for an engaging ethnographicstudy

on the Ann Summers parties in Britain. Here she investigates the links between social

class, the consumption of lingerie, and heterosexual femininity.

3. Despite past critiques (Marcus and Fischer 1986), I chose to privilege Mali-

nowski's instructions and attempt to "grasp the native's point of view" (Malinowski

1966:24). Inspired as well by Geertz (1974), this project emphasizes the ways individu-

als make sense of their sexual desires and practices. My ethnographicresearchrelied pri-

marily on participantobservation and semistructuredinterviews with over 30 women. I

learned about the home-based sex-toy parties the same way most people learn about

them, by word of month. Once I made contact with Jennifer Jolicoeur, owner of Athena's

Home Novelties (and secured approvalfrom the Institutional Review Broad at Rutgers),

I began attending the home-based product demonstrations. Prior to the demonstration,

the Athena's representative would introduce me to the group at large, explaining that I

taught at a nearbycollege and that I was conducting researchon sexuality. All of the par-

ticipants and informants have been assigned pseudonyms. However, the names of the

towns are actual communities in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The methodological

problems and epistemological issues involved in anthropological research on sexuality

have been documented (Kulick 1995).