Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Megara Stele

Transféré par

VoislavCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Megara Stele

Transféré par

VoislavDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

ALDO CORCELLA

P OL L I S AND T HE T AT T OOE RS

aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 109 (1995) 47–48

© Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn

47

POLLIS AND THE TATTOOERS*

In the year 1991, the Paul Getty Museum Journal (XIX, 136 no. 6) communicated the

acquisition of a funerary stele decorated with the relief of a hoplite and a Greek inscription.

The script was recognized as that of Megara, and the stele was dated to the early fifth centu-

ry B.C. The inscription was reported in SEG 40 (1990) 404, then, with an evident improve-

ment, by S. Follet in Bull. ép. 1992, 21 (p. 441) and in SEG 41 (1991) 413 (cf. no. 1883):

l°gO PÒlliw ÉAsOp¤xO f¤low h-

uiÒw Ú ‚ kakÚw §·n ép°ynaskon

hupÚ st[¤]ktaisin §g‡nE

A short commentary is appended (I implicitly correct some misprints): “The first line is

not metrical. For st¤kthw cf. Herondas, Mime 5.65, ‘tattooer’, Thracians? ‘I speak, I, Pollis

dear son of Asopichos, not having died a coward, with the wounds of the tattooers, yes

myself.’”

This commentary is susceptible of some improvement. f¤low uflÒw, “own son”, is not

quite obvious in a sentence in which the same Pollis is both grammatical subject and perso-

na loquens: it is in fact a hexametric cadence, maybe clumsily adopted (cf. e.g. Hansen,

CEG I 154). As for Pollis’s statement, oÈ is more naturally constructed with kakÚw §∆n to

form a definition of Pollis’s character (cf. §slÚw §≈n in CEG I 154): “I was no base man:

ÍpÚ st¤ktaisin I died”. The imperfect ép°ynaskon, in place of the usual (ép)°yanon, is

peculiar: with a plural subject, it would be iterative (cf. e.g. Il. I 383); here, the meaning

seems to be that Pollis, ill-treated by st¤ktai, gradually “died out”.

Who are these st¤ktai? st¤ktaisin can only be interpreted as the plural dative of

st¤kthw, the nomen agentis derived from st¤zein “to tattoo”, “to stamp”, “to brand” (for the

meanings of this verb, see U. Fantasia, Annali della Scuola Normale di Pisa s. III, VI [1976]

1165-1175). I see, however, no good reason for referring this expression to Thracians: while

stikto¤, picti, would be an appropriate antonomasia for them, st¤ktai is not. This word is,

indeed, attested in Herondas V 65. A further occurrence can be found in the account of an

Egyptian yhsaurÒw (P. Phil. 17.22, 2nd cent. A.D.), where – as the editor, J. Scherer,

remarked – the st¤kthw might be the same as the well-known §pisfragistÆw, the “stamper”

charged with the duty of “sealing” the vaults of the granaries (A. Calderini, Yhsauro¤,

Milano 1924, 86–87). The st¤ktai who caused Pollis’s death should, however, be compared

to Herondas’ st¤kthw, the “tattooer”, whom Bitinna would call for in order to have her slave

Gastron punished. In Greece, indeed, the imposition of st¤gmata was a treatment reserved

to kako¤ like slaves or criminals, and in some cases to prisoners of war (see C. P. Jones, JRS

LXXVII [1987] 146–151). Yet, Pollis was no kakÒw, but a brave hoplite. This explains the

* I am grateful to Prof. R. Merkelbach, who kindly gave me invaluable suggestions.

48 A. Corcella

emphasis of his words. He had fallen into the hands of the st¤ktai and had to face a

humiliating treatment: he was, maybe, questioned and tortured; in any case, his enemies

tried to impose the marks of slavery on him. But he (emphatic §g≈nh) was no base man (oÈ

kakÚw §≈n)! Therefore, his enemies could not make a slave of him. “Under the hands of

tattooers”, slavish people could submit and survive; he heroically resisted, until he died

(ép°ynaskon imperfect).

Pollis’s words imply, in sum, an opposition between his own noble death and the base

behaviour of other people. I would suggest that, at the time when the epitaph was written,

this opposition had a particular point. In his narrative of the Persian wars, Herodotus uses a

synonym of st¤ktai: in order to punish the Hellespont, rebellious to his authority, Xerxes

would have sent some stige›w, who symbolically “tattooed” the sea (VII 35.1). At Thermo-

pylae, Xerxes’ tattooers could display all their ability: when the Thebans went over to the

enemy, the st¤gmata basilÆia were tattooed on their bodies (Herodotus VII 233). The

historical authenticity of this episode has often been questioned (see e.g. R. J. Buck, The

Ancient History Bulletin I [1987] 54–60). Yet, Pollis’s epitaph could witness to the veracity

of Herodotus.

Pollis was from Megara. Now, in the war against Xerxes, the Megarians played an

important role, which was commemorated and celebrated in many a poem (cf. D. L. Page,

Further Greek Epigrams p. 213ff. ‘Simonides’ XVI; Simonides 11.37, ed. M. L. West,

Iambi et Elegi Graeci2). Megarian ships were present at both Artemisium and Salamis (Hdt.

VIII 1.1; 45); in spring 479, Mardonius moved from Boeotia and pushed as far as Megara,

where the cavalry overran the country (Hdt. IX 14; Paus. I 40.2, 44.4; cf. Theognis 773ff.);

after few weeks, the Megarians were badly defeated by the Theban horsemen at Plataeae

(Hdt. IX 69). In a word, the Megarians had more than one occasion to clash with those

Thebans who bore on their skins the infamous marks of their surrender to the Persians. It is

not impossible, therefore, that the epitaph of a Megarian warrior could allude to the Persians

as st¤ktai, thus mocking – and cursing – the hated Thebans too: while these slavishly

accepted the “royal tattooes”, Pollis “was no base man: under the hands of tattooers, he

died”.

Università della Basilicata, Potenza Aldo Corcella

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Books Villains of All Nations Atlantic Pirates in The Golden AgeDocument4 pagesBooks Villains of All Nations Atlantic Pirates in The Golden AgeVoislav0% (3)

- George Magazine - The Book of Political Lists-Villard (1998)Document402 pagesGeorge Magazine - The Book of Political Lists-Villard (1998)Blue Snowbelle100% (4)

- Segal, Kleos and Its Ironies in The Odyssey.Document27 pagesSegal, Kleos and Its Ironies in The Odyssey.Claudio CastellettiPas encore d'évaluation

- Leahy Amasis and ApriesDocument20 pagesLeahy Amasis and ApriesRo OrPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Lawrence Venuti, Translation Changes Everything (2013)Document2 pagesReview of Lawrence Venuti, Translation Changes Everything (2013)Anthony PymPas encore d'évaluation

- Lakas Sambayanan Video GuideDocument11 pagesLakas Sambayanan Video Guideapi-276813042Pas encore d'évaluation

- Delphi and The Homeric H Ymn To A PolloDocument18 pagesDelphi and The Homeric H Ymn To A PolloHenriquePas encore d'évaluation

- Nikolaev Argos MurioposDocument20 pagesNikolaev Argos MurioposalexandersnikolaevPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Greek Grave EpigrammesDocument13 pagesEarly Greek Grave EpigrammeslemcsPas encore d'évaluation

- Article BCH 0007-4217 1956 Num 80 1 2408Document21 pagesArticle BCH 0007-4217 1956 Num 80 1 2408aguaggentiPas encore d'évaluation

- Teatro Grecia y Roma. Asientos - BEARE, W. (1939)Document6 pagesTeatro Grecia y Roma. Asientos - BEARE, W. (1939)glorydaysPas encore d'évaluation

- Vernet PonsThe Etymology of Goliath, 2012Document22 pagesVernet PonsThe Etymology of Goliath, 2012Ro OrPas encore d'évaluation

- The Battle Exhortation in Ancient HistoriographyDocument21 pagesThe Battle Exhortation in Ancient HistoriographyRubén EscorihuelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Heraclitus in Verse: The Poetic Fragments of Scythinus of TeosDocument17 pagesHeraclitus in Verse: The Poetic Fragments of Scythinus of TeosunknownPas encore d'évaluation

- Sergent - Pylos Et Les EnfersDocument37 pagesSergent - Pylos Et Les EnfersMaurizio GallinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lebdev Unnoticed - Quotations - From - Heraclitus - inDocument22 pagesLebdev Unnoticed - Quotations - From - Heraclitus - injipnetPas encore d'évaluation

- Despre IliadaDocument16 pagesDespre IliadamoOnykPas encore d'évaluation

- Euripides "Telephus" Fr. 149 (Austin) and The Folk-Tale Origins of The Teuthranian ExpeditionDocument5 pagesEuripides "Telephus" Fr. 149 (Austin) and The Folk-Tale Origins of The Teuthranian Expeditionaristarchos76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fragmenta (-Um) .: Opp. Fr. GorgDocument14 pagesFragmenta (-Um) .: Opp. Fr. GorgwaltoakleyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Embassy and The Duals of Iliad PDFDocument14 pagesThe Embassy and The Duals of Iliad PDFAlvah GoldbookPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Tragedy and Sacrificial Ritual - Walter BurkertDocument39 pagesGreek Tragedy and Sacrificial Ritual - Walter BurkertAlejandra Figueroa100% (1)

- Greek Mime in The Roman Empire (413: Charition and Moicheutria)Document49 pagesGreek Mime in The Roman Empire (413: Charition and Moicheutria)Alia HanafiPas encore d'évaluation

- Burnett ArchilochusDocument21 pagesBurnett ArchilochusmarinangelaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Aulos Syrinx. in D. Castaldo F.G. Gi PDFDocument31 pagesThe Aulos Syrinx. in D. Castaldo F.G. Gi PDFAri MVPDLPas encore d'évaluation

- Leahy 1974Document24 pagesLeahy 1974F1 pdfPas encore d'évaluation

- Philagatos of Cerami, EkphraseisDocument34 pagesPhilagatos of Cerami, EkphraseisAndrei DumitrescuPas encore d'évaluation

- Philologus PildashDocument25 pagesPhilologus PildashEnokmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Klotz - Kemit Viii Zas 136Document5 pagesKlotz - Kemit Viii Zas 136dobazPas encore d'évaluation

- Heracleitus, Paradoxographer3Document47 pagesHeracleitus, Paradoxographer3Spyros MarkouPas encore d'évaluation

- Luraghi - 2002 - Helots Called Messenians A Note On Thuc 11012Document5 pagesLuraghi - 2002 - Helots Called Messenians A Note On Thuc 11012Anonymous Jj8TqcVDTyPas encore d'évaluation

- Orphics at Olbia?: 1 A Frontier CivilizationDocument10 pagesOrphics at Olbia?: 1 A Frontier CivilizationHolbenilordPas encore d'évaluation

- Linda Austin - Lament and Rhetoric of SublimeDocument29 pagesLinda Austin - Lament and Rhetoric of SublimeJimmy Newlin100% (1)

- J.D. Sauerländers VerlagDocument28 pagesJ.D. Sauerländers Verlagrealgabriel22Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bosworth1990 PDFDocument13 pagesBosworth1990 PDFSafaa SaiedPas encore d'évaluation

- This Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.134 On Wed, 17 Feb 2021 15:12:33 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.134 On Wed, 17 Feb 2021 15:12:33 UTCAlshaimaa MohammedPas encore d'évaluation

- Song of Antef-An Observation On The Harper S Song of TDocument7 pagesSong of Antef-An Observation On The Harper S Song of Tandre.capiteynpandora.bePas encore d'évaluation

- 505428Document16 pages505428LuciusQuietusPas encore d'évaluation

- Phoenix and The Achaean Embassy: Three Achaean Envoys To Achilles, Have, Since AnDocument13 pagesPhoenix and The Achaean Embassy: Three Achaean Envoys To Achilles, Have, Since AnAlvah GoldbookPas encore d'évaluation

- R. B. RUTHERFORD. Tragic Form and Feeling in The IliadDocument16 pagesR. B. RUTHERFORD. Tragic Form and Feeling in The IliadbrunoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sherk - THE EPONYMOUS OFFICIALS OF GREEK CITIES III PDFDocument38 pagesSherk - THE EPONYMOUS OFFICIALS OF GREEK CITIES III PDFFatih YılmazPas encore d'évaluation

- Calos Graffiti and Infames at Pompeii.Document10 pagesCalos Graffiti and Infames at Pompeii.jfmartos2050Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Judgement of Paris in Later Byzantine Literature Author(s) : Elizabeth M. Jeffreys Source: Byzantion, 1978, Vol. 48, No. 1 (1978), Pp. 112-131 Published By: Peeters PublishersDocument21 pagesThe Judgement of Paris in Later Byzantine Literature Author(s) : Elizabeth M. Jeffreys Source: Byzantion, 1978, Vol. 48, No. 1 (1978), Pp. 112-131 Published By: Peeters PublisherscerealinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arnott. The Alphabet Tragedy of CalliasDocument4 pagesArnott. The Alphabet Tragedy of CalliasMariana Gardella HuesoPas encore d'évaluation

- Aeschylus Agamemnon 78 No Room For Ares PDFDocument6 pagesAeschylus Agamemnon 78 No Room For Ares PDFალექსანდრე იაშაღაშვილიPas encore d'évaluation

- Verbetes Da Enciclopédia PaulyDocument8 pagesVerbetes Da Enciclopédia PaulyÍvina GuimarãesPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 2307@267080Document3 pages10 2307@267080Felipe MontanaresPas encore d'évaluation

- The Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionDocument8 pagesThe Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionAankh BenuPas encore d'évaluation

- Of Dogs and Men: Archilochos, Archaeology and The Greek Settlement of ThasosOwen 2003Document19 pagesOf Dogs and Men: Archilochos, Archaeology and The Greek Settlement of ThasosOwen 2003Thanos SiderisPas encore d'évaluation

- Edwards - 1993 - A Portrait of PlotinusDocument11 pagesEdwards - 1993 - A Portrait of PlotinusFritzWaltherPas encore d'évaluation

- The History of A Greek ProverbDocument32 pagesThe History of A Greek ProverbAmbar CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Ypsilanti LeonidasfishermenDocument8 pagesYpsilanti LeonidasfishermenmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Leo The Philosopher WESTERINKDocument30 pagesLeo The Philosopher WESTERINKJulián BértolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Capps E Page E T and Rouse D H W Thucydides History of The Peloponnesian War Book I and IIDocument512 pagesCapps E Page E T and Rouse D H W Thucydides History of The Peloponnesian War Book I and IIMarko MilosevicPas encore d'évaluation

- Apophis: On The Origin, Name, and Nature of An Ancient Egyptian Anti-GodDocument6 pagesApophis: On The Origin, Name, and Nature of An Ancient Egyptian Anti-Godmai refaat100% (1)

- How To WriteDocument19 pagesHow To WriteRaquel Fornieles SánchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes and Discussions: F3Ao-Xlrco Tev8Aprc&ParDocument6 pagesNotes and Discussions: F3Ao-Xlrco Tev8Aprc&ParCarlos I. Soto ContrerasPas encore d'évaluation

- Apotropaic Symbolism LibreDocument9 pagesApotropaic Symbolism LibreFilip BaruhPas encore d'évaluation

- Homeric Formularity in The ArgonauticaDocument52 pagesHomeric Formularity in The ArgonauticaEmilio JrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Etymology of Greek MythologyDocument17 pagesEtymology of Greek Mythologyarienim67% (3)

- Iliad and Alexiad PDFDocument8 pagesIliad and Alexiad PDFValee Gonzalez MoyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Herodoto. New PaulyDocument7 pagesHerodoto. New PaulyNestor ChuecaPas encore d'évaluation

- AristophanesfrogsDocument11 pagesAristophanesfrogsahorrorizadaPas encore d'évaluation

- SymbolsDocument1 pageSymbolsVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Ubsm Ubsm SRK Cor 0027 HighDocument221 pagesUbsm Ubsm SRK Cor 0027 HighVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Alan Ford Brojevi Od Pet MetakaDocument3 pagesAlan Ford Brojevi Od Pet MetakaVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Latin PaleographyDocument82 pagesLatin PaleographyJacob GerberPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018-04-30 20 - 40 - 50 PDFDocument1 page2018-04-30 20 - 40 - 50 PDFVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Non Ethnic Motivations For Bosnian WarDocument55 pagesNon Ethnic Motivations For Bosnian WarvisaslavePas encore d'évaluation

- 2018-04-30 20 - 40 - 50Document1 page2018-04-30 20 - 40 - 50VoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Conquerors and Serfs PDFDocument26 pagesConquerors and Serfs PDFVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Agora SpearheadDocument1 pageAgora SpearheadVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- NothingnessDocument1 pageNothingnessVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- NothingnessDocument2 pagesNothingnessVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- El Mejor de Lo MejorDocument7 pagesEl Mejor de Lo MejorSANMARTINPas encore d'évaluation

- Paper Accepted Current Topic / Актуелна тема Personal View / Лични ставDocument10 pagesPaper Accepted Current Topic / Актуелна тема Personal View / Лични ставVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018-06-02 19 - 36 - 29Document1 page2018-06-02 19 - 36 - 29VoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- PossibilitiesDocument1 pagePossibilitiesVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Something He Couldnt Write About - Telling My Daddys Story of VietDocument12 pagesSomething He Couldnt Write About - Telling My Daddys Story of VietVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Pirates Raiders and Soldiers of FortuneDocument4 pagesPirates Raiders and Soldiers of FortuneVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancestral Custom War Dead in Ancient GREDocument8 pagesAncestral Custom War Dead in Ancient GREVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018-06-24 18 - 24 - 42Document1 page2018-06-24 18 - 24 - 42VoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Takeda Shingen - The Limits of Perseverance and AmbitionDocument6 pagesTakeda Shingen - The Limits of Perseverance and AmbitionVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Race in Armor Race With Shields The Orig PDFDocument23 pagesRace in Armor Race With Shields The Orig PDFVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Contextualizing Symbols. The Eagle andDocument24 pagesContextualizing Symbols. The Eagle andbrenda9tovarPas encore d'évaluation

- Pirates Raiders and Soldiers of FortuneDocument4 pagesPirates Raiders and Soldiers of FortuneVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Megara SteleDocument4 pagesMegara SteleVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Contextualizing Symbols. The Eagle andDocument24 pagesContextualizing Symbols. The Eagle andbrenda9tovarPas encore d'évaluation

- Neils J. Ed. GODDESS AND POLIS. THE PANA PDFDocument3 pagesNeils J. Ed. GODDESS AND POLIS. THE PANA PDFVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- And Did Those FeetDocument29 pagesAnd Did Those FeetVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Homer 1715-1996 - Homer Critical Assessments by Irene J. F. DeJDocument8 pagesHomer 1715-1996 - Homer Critical Assessments by Irene J. F. DeJVoislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Science Part 1 of 3Document73 pagesSocial Science Part 1 of 3Himank BansalPas encore d'évaluation

- Iwakuni Approach 12nov10Document7 pagesIwakuni Approach 12nov10stephanie_early9358Pas encore d'évaluation

- aBC CG Land Revenue QuestionsDocument2 pagesaBC CG Land Revenue QuestionsAmuree MusicPas encore d'évaluation

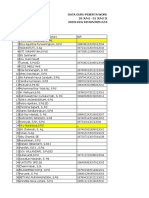

- Data Peserta WS IKM 29-31 Mei - UH - Per 9 Juni 2023Document6 pagesData Peserta WS IKM 29-31 Mei - UH - Per 9 Juni 2023Muhammad Insan Noor MuhajirPas encore d'évaluation

- Atal Bihari VajpayeeDocument11 pagesAtal Bihari VajpayeeDevyani ManiPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 185664Document14 pagesG.R. No. 185664Anonymous KgPX1oCfrPas encore d'évaluation

- Study 9 Vol 1 Adult STSDocument3 pagesStudy 9 Vol 1 Adult STSMORE THAN CONQUERORS INNOVAPas encore d'évaluation

- 59807-Article Text-181733-1-10-20221125Document24 pages59807-Article Text-181733-1-10-20221125golanevan71Pas encore d'évaluation

- Speakout DVD Extra Starter Unit 02Document1 pageSpeakout DVD Extra Starter Unit 02lkzhtubcnhfwbbgjxnsPas encore d'évaluation

- Guevent vs. PlacDocument1 pageGuevent vs. PlacMarianne AndresPas encore d'évaluation

- Property Case OutlineDocument66 pagesProperty Case OutlineMissy MeyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Advisory - 27nov2020Document3 pagesAdvisory - 27nov2020Azim AfridiPas encore d'évaluation

- Quizizz - Simile, Metaphor, Hyperbole, Oxymoron, and IdiomsDocument3 pagesQuizizz - Simile, Metaphor, Hyperbole, Oxymoron, and Idiomsenchantinglavender127Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aam Aadmi Party WikiDocument3 pagesAam Aadmi Party WikiVarun NehruPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax Notes TodayDocument2 pagesTax Notes TodayThe Washington PostPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is An Amulet or A TaweezDocument4 pagesWhat Is An Amulet or A TaweezAli AdamPas encore d'évaluation

- Solodarity Domestic Voilance in IndiaDocument225 pagesSolodarity Domestic Voilance in IndiaShashi Bhushan Sonbhadra100% (1)

- Chapter 4 Network SecurityDocument10 pagesChapter 4 Network SecurityalextawekePas encore d'évaluation

- MonologuesDocument8 pagesMonologuesMiss Mimesis100% (2)

- Grade11 2ND AssessmentDocument2 pagesGrade11 2ND AssessmentEvangeline Baisac0% (1)

- Fundamental Rights Upsc Notes 71Document4 pagesFundamental Rights Upsc Notes 71imteyazali4001Pas encore d'évaluation

- Williams Homelessness March12Document6 pagesWilliams Homelessness March12Rasaq MojeedPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ResearchDocument18 pagesFinal ResearchJean CancinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Model United Nations: A Basic Guide by Your Very Own @acofriane (IG)Document38 pagesModel United Nations: A Basic Guide by Your Very Own @acofriane (IG)Ayati gargPas encore d'évaluation

- KrampusDocument3 pagesKrampusVanya Vinčić100% (1)

- Full Manpower Satorp ProjectDocument4 pagesFull Manpower Satorp ProjectBenjie dela RosaPas encore d'évaluation