Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A - I Prepare

Transféré par

diyah halimTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A - I Prepare

Transféré par

diyah halimDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/261292885

Adherence therapy following acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: A

randomised controlled trial in Thailand

Article in International Journal of Social Psychiatry · April 2014

DOI: 10.1177/0020764014529099 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

12 237

3 authors, including:

Suparpit Von bormann Richard Gray

Boromarajonani College of Nursing Changwat Nonthaburi, Thailand La Trobe University

15 PUBLICATIONS 68 CITATIONS 217 PUBLICATIONS 3,485 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Nurse prescribing in a developing country: What do physicians and nurses think? View project

NUGAT Nurse graduateness and patient mortality View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Richard Gray on 11 September 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

International Journal of Social Psychiatry

http://isp.sagepub.com/

Adherence therapy following acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: A randomised controlled trial in

Thailand

Suparpit von Bormann, Deborah Robson and Richard Gray

Int J Soc Psychiatry published online 1 April 2014

DOI: 10.1177/0020764014529099

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://isp.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/04/01/0020764014529099

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for International Journal of Social Psychiatry can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://isp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://isp.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://isp.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/04/01/0020764014529099.refs.html

>> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Apr 1, 2014

What is This?

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

529099

research-article2014

ISP0010.1177/0020764014529099International Journal of Social Psychiatryvon Bormann et al.

E CAMDEN SCHIZOPH

Article

International Journal of

Adherence therapy following acute Social Psychiatry

1–7

© The Author(s) 2014

exacerbation of schizophrenia: A Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

randomised controlled trial in Thailand DOI: 10.1177/0020764014529099

isp.sagepub.com

Suparpit von Bormann1, Deborah Robson2 and Richard Gray3

Abstract

Background: Up to 50% of patients with schizophrenia are non-adherent with antipsychotic medication.

Aims: To establish the efficacy of adherence therapy (AT) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) in improving clinical

outcomes in patients with schizophrenia following an acute exacerbation of illness.

Method: A parallel-group, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Fieldwork was conducted in Thailand. Patients

received eight weekly sessions of AT in addition to TAU. The primary outcome was improvement in psychopathology

(measured using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)) at 26-week follow-up. Secondary outcomes

included patient attitudes towards medication, global functioning and side-effects.

Results: In total, 70 inpatients with schizophrenia were recruited to the trial. At 26-week follow-up, PANSS total scores

improved in the AT compared to the TAU group by a mean of −3.94 points (effect size = 0.24). The number needed to

treat (NNT) was 5. There was no significant effect on patients’ attitudes towards treatment, functioning or medication

side-effects. No treatment-related adverse effects were reported.

Conclusion: AT improves psychopathology in Asian patients with schizophrenia following an acute exacerbation of

illness.

Keywords

Adherence, compliance, antipsychotic, schizophrenia

Introduction

Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic medication is 2013; Gray et al., 2006; Gray, Wykes, Edmonds, Leese, &

effective at preventing relapse in schizophrenia (Leucht Gournay, 2004; Kemp, Hayward, Applewhaite, Everitt, &

et al., 2012) but requires that patients are compliant. In David, 1996; Kemp, Kirov, Everitt, Hayward, & David,

common with other long-term conditions, around 50% of 1998; O’Donnell et al., 2003; Schulz et al., 2013; Staring

patients with schizophrenia are non-adherent with medica- et al., 2010). Trials have also been conducted in America

tion (Lacro, Dunn, Dolder, Leckband, & Jeste, 2002). (Anderson et al., 2010; Byerly, Fisher, Carmody, & Rush,

Non-adherence is associated with an increased risk of 2005) and Australia (Cavezza, Aurora, & Ogloff, 2013).

relapse, hospital admission and having persistent psy- The majority (9/13) have reported positive findings,

chotic symptoms (Morken, Widen, & Grawe, 2008). although the largest trial (Gray et al., 2006) that involved

Factors consistently associated with non-adherence 409 patients reported negative findings.

include poor insight, negative treatment/illness beliefs,

past non-adherence and a poorer therapeutic relationship

(Lacro et al., 2002). Effective interventions to enhance 1Head of the Research Division, Boromarajonani College of Nursing

adherence are required. Changwat Nonthaburi, Nonthaburi, Thailand

2Section of Mental Health Nursing, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s

Adherence (nee compliance) therapy (AT) is a brief

College London, London, UK

psychological intervention based on motivational inter- 3Academic Department of Education and Research, Hamad Medical

viewing and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) that Corporation, Doha, Qatar

aims to enhance adherence and improve clinical outcomes

Corresponding author:

for patients with schizophrenia. To date, there have been Richard Gray, Academic Department of Education and Research,

13 trials of AT involving 1197 patients, predominately Hamad Medical Corporation, P.O. Box 3050, Doha, Qatar.

conducted in Europe (Brown, Gray, Jones, & Whitfield, Email: rgray@hmc.org.qa

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

2 International Journal of Social Psychiatry

Rates of treatment non-adherence in Asian patients Because of the potential to limit participants’ engage-

with schizophrenia are similar to those in Western popula- ment with AT patients with organic brain disease, or mod-

tions. There have only been two published trials erate to severe learning disability, those who did not speak

(Maneesakorn, Robson, Gournay, & Gray, 2007; Tsang & fluent Thai were also excluded.

Wong, 2005) involving 110 patients who have tested AT in Towards the end of their inpatient admission, patients

this population; the latter was an exploratory trial that were approached by a member of the treating clinical team

informed this study. The aim in this trial was to test the to enquire if they would consider participating in the trial.

effectiveness of AT in Thai patients following an acute If they expressed interest in the study a researcher com-

exacerbation of schizophrenia. pleted a screening checklist to determine their eligibility

and obtained written informed consent.

Methods

Ethical approval

A parallel-group, single-blind, randomised controlled trial

(RCT) of adherence therapy compared to treatment as Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute of

usual (TAU) in patients with schizophrenia following an Psychiatry, King’s College London, and the Thai Ministry

inpatient hospital admission because of an acute exacerba- of Public Health. Written informed consent was obtained

tion of schizophrenia. Patients were randomised on a one- from all patients participating in the trial.

to-one basis. Researchers who were blind to group

allocation completed assessments. The fieldwork for this

study was conducted in a large psychiatric hospital in

Sample size

Thailand. The trial adhered strictly to Consolidated We calculated that 70 patients would be required for this

Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). trial. Based on our pilot trial (Maneesakorn et al., 2007),

we estimated a 15-point difference in PANSS totals scores

between the AT and TAU groups at the week 26 assess-

Objectives ment. Our power calculation was based on the following

The primary objective of this trial was to determine the assumptions: a standard deviation of 17, an alpha of .05, a

effectiveness of AT compared to TAU in improving psy- 2-tailed test of significance, 90% power and that 30% of

chopathology at 26-week follow-up. Secondary objec- patients would withdraw.

tives were to evaluate the effectiveness of AT at 26-week

follow-up compared to TAU in improving patients’ atti-

Setting

tudes towards medication, global functioning and side-

effects of medication. A tertiary objective was to explore Patients were recruited from 10 inpatient units in Sanprung

predictors of clinically significant improvement in Psychiatric Hospital in Chiang Mai, located in the North of

psychopathology. Thailand. The hospital is responsible for 97,115 psychiat-

ric patients (0.7% of the 15 million people living in 15

northern Thai provinces). The average length of inpatient

Participants stay is approximately 1 month.

We included male and female patients over the age of 20

with a case note Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Outcome measures

Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis of

schizophrenia (American Psychiatric Association (APA), The primary outcome was improvement in psychopathol-

2000) who were admitted for inpatient treatment because ogy, measured using the Thai version of the Positive and

of acute exacerbation of their psychosis. The rationale for Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-T). The PANSS-T has

these criteria was that in some trials AT has been shown to established psychometric properties in Thai patients with

be most effective just following an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia (Nilchaikovit, Uneanong, Kessawai, &

illness. Patients were excluded if Thomyangkoon, 2000). Secondary outcomes included

patient attitudes towards medication measured using the

•• They had suicidal ideas or behaviours, because of Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI-30) (Hogan, Awad, &

the associated risks of conducting research in this Eastwood, 1983); global functioning, determined using the

group. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF ) Scale (Hall,

•• There was case note evidence of drug or alcohol 1995); and side-effects of medication assessed using the

dependence, as substance abuse has been shown to Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effects Rating

negatively affect medication adherence. Addressing Scale (LUNSERS; Day, Wood, Dewey, & Bentall, 1995).

these behaviours is not part of AT. The PANSS and GAF were already available in Thai. The

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

von Bormann et al. 3

DAI-30 and the LUNSERS required translation. Details of AT is rooted in the observation that patients’ beliefs

the translation process used are described elsewhere impact on medication compliance. A patient-centred

(Maneesakorn et al., 2007). All measures were adminis- manualised approach, AT is delivered as a course over a

tered at baseline and 26-week follow-up by research assis- series of eight one-to-one sessions, each with a different

tants who had been trained to administer the assessments focus. The fundamental clinical skills of adherence ther-

in a standard way and were blind to treatment allocation. apy include agenda setting, using the patient’s own lan-

Researchers completed the measures in the outpatient guage, collaborative working, linking sessions together

clinic or in the patients’ own home dependent on patient and reflective listening. The four cornerstones of AT are

preference. For the PANSS, we established a high degree keeping the patient engaged, minimising resistance to

of inter-rater reliability (r = 0.71, 95% confidence interval change, providing information required by the patient

(CI) 0.48, 0.85) between researchers. about medication and side-effects and using Socratic dia-

logue to generate discrepancies in patients’ beliefs about

treatment. Within this framework there are specific AT

Randomisation

exercises:

Randomisation was undertaken by an independent ran-

domisation service. For allocation of the participants, a 1. Assessment by exploring patients’ beliefs about

computer-generated list of random numbers was used. treatment, practical problems with medication and

Patients were randomly assigned following simple ran- side-effects and medicines reconciliation (review-

domisation procedures to AT or TAU. The nurse therapist ing all medication, prescribed or otherwise, patients

(Suparpit von Bormann (S.v.B.)) delivering the interven- are taking).

tion had the contact details of all patients involved in the 2. Structured medication problem solving to address

study. S.v.B. was contacted by the randomisation service practical issues with medication, for example, side-

and was told which group patients had been allocated to. effects or remembering to take medication.

They then arranged assessment and, in the AT group, visits 3. Using a medication timeline to help patients review

to deliver the intervention. Researchers were not able to past experiences of illness and treatment.

access any information about group allocation and were 4. Exploring patients’ ambivalence about taking med-

instructed not to ask patients if they had received any addi- ication using a decisional matrix (the pros and cons

tional therapy from a nurse. of taking/not taking medication).

5. Testing patients beliefs about medication, for

example, ‘I can stop medication once I start to feel

Statistical methods well,’ ‘taking medication is unnatural,’ ‘medication

All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. is a slow acting poison’.

Outcomes were analysed using SPSS v14 (SPSS, Inc., 6. Helping patients to move forward in their lives, to

2005). Most outcome variables were not normally distrib- consider ‘life goals’ and the role medication may

uted at baseline, and log transformation was not consid- play in achieving these.

ered to be appropriate when statistical advice was sought.

The effect of the intervention was determined using analy- TAU group: TAU included medication, vocational and

sis of covariance (ANCOVA) and regression analysis. recreational therapy and outreach community psychiatric

Effect size was calculated using the t-test for the signifi- support.

cance of the product–moment correlation coefficient that

is suitable for unequal sample sizes. Binary logistic regres-

Results

sion analysis was used to identify predictors of clinically

significant improvement defined as a 25% or more reduc- Fieldwork was conducted from 1 November 2004 to 31

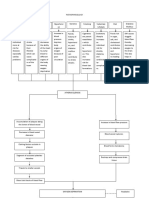

tion in PANSS total scores (Csernansky, Mahmoud, & October 2005. Figure 1 shows the flow of patients through

Brenner, 2002). the trial. Of 155 patients screened to participate, 76 met the

inclusion criteria. Six patients did not participate because

they were living outside of the hospital catchment area or

Interventions refused to take part. A total of 70 patients were randomly

Patients in the intervention group received eight sessions assigned into two groups. Two patients in the AT group

of AT as an add-on to TAU. A trained nurse therapist were lost to follow-up at the 26-week assessment. One was

(S.v.B.) delivered all sessions. S.v.B received approxi- discharged and could not be contacted; the other moved

mately 40 hours of AT training and regular clinical super- out of the area and did not leave a forwarding address.

vision from the third author (R.G.) and the second author Missing data were handled using last observation carried

(D.R.), who developed and manualised the intervention. forward (LOCF).

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

4 International Journal of Social Psychiatry

Figure 1. AT for schizophrenia.

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics of participants.

AT group n = 38 n (%) TAU group n = 32 n (%)

Age (mean, SD) 38 (11) 50 (9)

Male 27 (71) 25 (78)

Has a caregiver 32 (84) 20 (62)

Thai 38 (100) 32 (100)

No income 30 (79) 21 (66)

Finished secondary education 17 (45) 14 (44)

AT: adherence therapy; TAU: treatment as usual; SD: standard deviation.

A number of important baseline differences in demo- All patients received eight sessions of AT. The mean

graphic characteristics were observed between the AT duration of each session was 41 minutes (standard devia-

and TAU groups. Patients in the TAU group were older, tion (SD) = 8) and ranged from 23 to 57 minutes. In total,

less likely to have a carer and more likely to be working patients received 5 hours and 25 minutes (SD = 1.16) of

(Table 1). AT.

The clinical characteristics of the two groups were

broadly similar at trial entry. Average dosages of antipsy-

Outcomes

chotics (in chlorpromazine equivalents) were, respectively,

332 and 329 mg/day for the AT and TAU groups. At base- Compared to TAU, AT significantly improved patients’

line, 11 of 38 patients (29%) in the AT group and 9 of 32 psychopathology (Table 3) representing a small effect size

(28%) in the TAU group were prescribed clozapine. At (ES = 0.24). There were no significant differences in treat-

trial entry, the acute phase of the patients’ illness had ment attitudes, functioning or side-effects between AT and

passed and they had generally positive attitudes towards TAU. No treatment-related serious untoward incidents

their medication. The TAU group had better global func- were reported.

tioning and experienced more side-effects than the AT PANSS baseline scores were the only significant pre-

group (Table 2). dictor of clinical improvement at follow-up (Exp (B) =

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

von Bormann et al. 5

Table 2. Baseline clinical characteristics of participants.

AT group n = 38 (mean, SD) TAU group n = 32 (mean, SD)

Length of illness (years) 11 (8) 11 (8)

Number of previous admissions to hospital 9 (6) 10 (8)

Mean dose of antipsychotic medication (in 332 (26) 329 (30)

chlorpromazine equivalent, mg/day)

Prescribed depot (long-acting) medication (n, %) 12 (32) 10 (31)

Symptoms (PANSS total) 47 (16) 48 (16)

Treatment attitudes (DAI-30) 16 (9) 16 (8)

Functioning (GAF) 50 (14) 62 (17)

Side-effects (LUNSERS-total) 12 (12) 16 (15)

AT: adherence therapy; TAU: treatment as usual; SD: standard deviation; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; DAI: Drug Attitude Inven-

tory; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; LUNSERS: Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effects Rating Scale.

Table 3. Outcome measures at baseline and follow-up according to treatment group.

Measure Adherence therapy (n = 38) Treatment as usual (n = 32) Comparison of change scores between groups

(ANCOVA)

26 weeks Change Mean 26 weeks Change Mean Difference F (df) p T (df) ES

Mean (SD) (SD) Mean (SD) (SD) (AT−TAU) Mean

(95% CI)

PANSS* 43.13 (13.92) −3.63 (13.42) 48.50 (15.42) 0.31 (21.00) −3.94 (−12.22, 4.33) 4.25 (60) 0.04 2.06 (68) 0.24

DAI-30† 20.11 (4.79) 4.37 (8.59) 18.91 (7.24) 3.00 (8.65) 1.37 (−2.76, 5.49) 1.84 (60) 0.18 −1.36 (68) 0.16

GAF† 74.53 (12.86) 24.64 (16.55) 72.78 (13.42) 11.06 (24.62) 13.58 (−3.69, 23.44) 0.16 (60) 0.69 −0.40 (68) −0.05

LUNSERS* 16.95 (13.98) 4.53 (19.07) 12.50 (12.74) −3.63 (19.39) 8.16 (−1.05, 17.35) 0.98 (60) 0.33 −0.99 (68) −0.14

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; AT: adherence therapy; TAU: treatment as usual; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; df: difference;

ES: effect size; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; DAI: Drug Attitude Inventory; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; LUNSERS:

Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effects Rating Scale.

*Negative value of change suggests improvement.

†Positive value of change suggests improvement.

1.10, 95% CI = [1.04, 1.15], p < .01) accounting for 83% with varying levels of caregiver support. The results sug-

of the variance. gest that a range of patients, from those with a relatively

Number needed to treat (NNT) is defined as the number short duration of illness and only a single previous admis-

of patients who must be treated to prevent one additional sion to those that have been unwell for many years and

adverse event. For the purposes of this trial, this was have had several previous admissions, can benefit from AT

defined as any patient that experienced a relapse of their following an acute episode of illness.

psychosis (a minimum 25% increase in PANSS total As in the initial Kemp et al. (1996, 1998) and Schulz

scores). In the AT and TAU groups, 17 (45%) and 21 et al. (2013) studies, participants in this trial were recruited

patients (66%), respectively, met these criteria. We calcu- following an acute episode of psychosis. Other trials (Gray

lated that five patients (95% CI 4.53, 4.99) needed to be et al., 2006) have recruited patients who have been clini-

treated with AT to prevent one relapse. cally stable and community dwelling. This is a potentially

important difference between the studies. It may be that

the most opportune moment to tackle adherence is follow-

Discussion ing an acute episode of illness of admission to hospital.

The objective of this trial was to establish the effectiveness Authors of Crisis Theory (Caplan, 1964) argue that it is

of AT compared to TAU in improving psychopathology in just after a crisis event that people are most amenable to

Thai patients with schizophrenia at 26-week follow-up. changing behaviour. Schulz et al. (2013) suggest that it is

The results of this trial suggest that AT is effective at treat- immediately following an acute episode of illness that AT

ing schizophrenia symptoms in Asian patients with schizo- should be applied. The findings of this trial are consistent

phrenia with a NNT of 5. with this hypothesis.

AT was delivered, following an acute exacerbation of Since 1996, there have been 13 trials of AT (Anderson

their psychosis, to adult, Thai, men and women, with a et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2013; Byerly et al., 2005;

range of income, different educational background and Cavezza et al., 2013; Gray et al., 2004, 2006; Kemp et al.,

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

6 International Journal of Social Psychiatry

1996, 1998; Maneesakorn et al., 2007; O’Donnell et al., Future research

2003; Schulz et al., 2013; Staring et al., 2010; Tsang &

Wong, 2005). This trial replicates and extends the work of The results of AT trials are mixed. The findings from this

Kemp et al. (1996, 1998) and others (Brown et al., 2013; and other recent trials suggest that AT is perhaps most

Cavezza et al., 2013; Gray et al., 2004; Maneesakorn et al., effective following a psychiatric crisis. A case can perhaps

2007; Schulz et al., 2013; Staring et al., 2010; Tsang & now be made for a full trial of AT in this population. It is

Wong, 2005) who reported AT is effective at treating important to note that any such trial should pay close atten-

schizophrenia and suggests the intervention can be applied tion to challenges of recruiting non-adherent patients with

into a culturally different Thai population of patients. schizophrenia to their trial. The importance of effective

However, the effect size in this trial was smaller than in sampling and recruitment strategies in such a study cannot

our own exploratory (Maneesakorn et al., 2007) trial, be underestimated. There is a real risk that if these issues

where we reported a large effect size (ES = 0.56). are not addressed a potentially effective schizophrenia

We chose to use symptoms, measured using the PANSS treatment may be rejected because it has not been tested on

and not adherence as our primary outcome for this trial. the right patients.

There is no valid and reliable measure of medication

adherence; pill counts, clinician rating and belief/attitude Conclusion

scales have been used but authors report only a weak cor-

relation between them (Gray et al., 2006). Enhancing The results of this adequately powered RCT suggest that

adherence without showing that clinical outcomes have AT is an effective intervention in an Asian population of

improved is meaningless to patients and perhaps unethical. patients following an acute episode of schizophrenia.

In this trial, we observed only modest improvements in

patients’ symptoms. In part, this may be explained by the Acknowledgements

lower level of psychopathology patients were experienc- We thank all the participants including clinicians, nurses and

ing at baseline compared to those in our pilot study (a pos- patients for their support in the trial (ISRCTN: 74277581; the

sible ceiling effect). The more modest effect we observed Current Controlled Trials Limited).

in this compared to previous trials may also be explained

by differences in duration of follow-up; in the first trial, Contributors

patients were followed up after 9 weeks (after completion R.G., D.R. and S.v.B. designed the study. S.v.B. delivered the

of the intervention), and in this trial follow-up was at 26 therapy, analysed data and coordinated the study. S.v.B. wrote

weeks. This observation may suggest that the effects of AT the initial draft. All authors finalised the manuscript and approved

in an Asian population degrade over time. the final document. R.G. is the guarantor for the study.

Conflict of interest

Limitations S.v.B. and D.R. have no conflicts of interest. R.G. has received

The use of TAU as the control condition is a limitation of honoraria and provided consultancy to AstraZeneca, Bristol-

our study because it does not control for the non-specific Myers Squibb, Jannsen Cilag, Eli Lilly and Co. and Otsuka

effects of a mental health worker spending regular time Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd.

with a patient. While the provision of a control interven-

Full protocol

tion might have strengthened the design of our trial, we felt

that it was ethically dubious engaging patients in a time- A copy of the trial protocol can be obtained from the correspond-

consuming treatment that had been specifically designed ing author on request.

to be inert.

Funding

That patients at the start of the study were generally

adherent, potentially restricting the effect of AT, is a fur- The Royal Thai Government provided a PhD scholarship for

ther limitation of our trial. Sufficiently strict inclusion cri- S.v.B.

teria ensuring that only non-adherent patients were

References

included should have been applied.

In this study, there was a single therapist who, it might American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2000). Diagnostic

be argued, had a high level of motivation to demonstrate and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.).

Washington, DC: Author.

the effectiveness of AT. The study could have been

Anderson, K., Ford, S., Robson, D., Cassis, J., Rodrigues, C.,

strengthened if there were more therapists delivering the

& Gray, R. (2010). An exploratory, randomized controlled

intervention. Therapist fidelity to AT was not monitored; trial of adherence therapy for people with schizophrenia.

consequently we cannot determine how faithfully the International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 19, 340–

intervention was delivered. Other AT trials (Gray et al., 349.

2006) have monitored fidelity and our study would have Brown, E., Gray, R., Jones, M., & Whitfield, S. (2013).

been enhanced if we had used these procedures. Effectiveness of adherence therapy in patients with early

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

von Bormann et al. 7

psychosis: A mirror image study. International Journal of Lacro, J. P., Dunn, L. B., Dolder, C. R., Leckband, S. G., &

Mental Health Nursing, 22, 24–34. Jeste, D. V. (2002). Prevalence of and risk factors for medi-

Byerly, M. J., Fisher, R., Carmody, T., & Rush, A. J. (2005). cation non-adherence in patients with schizopohrenia: A

A trial of compliance therapy in outpatients with schizo- comprehensive review of the literature. Journal of Clinical

phrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63, 892–909.

Psychiatry, 66, 997–1001. Leucht, S., Tardy, M., Komossa, K., Heres, S., Kissling, W.,

Caplan, G. (1964). Principles of preventive psychiatry. New Salanti, G., & Davis, J. M. (2012). Antipsychotic drugs

York, NY: Basic Books. versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia:

Cavezza, C., Aurora, M., & Ogloff, R. P. (2013). The effects of A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 379,

an adherence therapy approach in a secure forensic hos- 2063–2071.

pital: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Forensic Maneesakorn, S., Robson, D., Gournay, K., & Gray, R. (2007).

Psychiatry & Psychology, 24, 458–478. An RCT of adherence therapy for people with schizophrenia

Csernansky, J. G., Mahmoud, R., & Brenner, R. (2002). A com- in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16,

parison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention 1302–1312.

of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. New England Morken, G., Widen, J. H., & Grawe, R. W. (2008). Non-adherence

Journal of Medicine, 346, 16–22. to antipsychotic medication, relapse and rehospitalisation in

Day, J. C., Wood, G., Dewey, M., & Bentall, R. P. (1995). A recent-onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 32.

self-rating scale for measuring neuroleptic side-effects: Nilchaikovit, T., Uneanong, S., Kessawai, D., & Thomyangkoon,

Validation in a group of schizophrenic patients. British P. (2000). The Thai version of the Positive and Negative

Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 650–653. Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia: Criterion

Gray, R., Leese, M., Bindman, J., Becker, T., Burti, L., David, validity and interrater reliability. Journal of the Medical

A., … Tansella, M. (2006). Adherence therapy for people Association of Thailand, 83, 646–651.

with schizophrenia: European multicentre randomised con- O’Donnell, C., Donohoe, G., Sharkey, L., Owens, N., Migone,

trolled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 189, 508–514. M., Harries, R., … O’Callaghan, E. (2003). Compliance

Gray, R., Wykes, T., Edmonds, M., Leese, M., & Gournay, K. therapy: A randomised controlled trial in schizophrenia.

(2004). Effect of a medication management training pack- British Medical Journal, 327, 834.

age for nurses on clinical outcomes for patients with schizo- Schulz, M., Gray, R., Spiekermann, A., Abderhalden, C.,

phrenia: Cluster randomised controlled trial. British Journal Behrens, J., & Driessen, M. (2013). Adherence therapy fol-

of Psychiatry, 185, 157–162. lowing an acute episode of schizophrenia: A multi-centre

Hall, R. C. W. (1995). Global assessment of functioning: A mod- randomised controlled trial. Schizophrenia Research, 146,

ified scale. Psychosomatics, 36, 267–275. 59–63.

Hogan, T. P., Awad, A. G., & Eastwood, R. (1983). A self- SPSS, Inc. (2005). Statistical package for the social sciences

report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophren- 14.0. Chicago, IL: Author.

ics: Reliability and discriminative validity. Psychological Staring, A. B. P., Van der Gaag, M., Koopmans, G. T., Selten,

Medicine, 13, 177–183. J. P., Van Beveren, J. M., Hengeveld, M. W., … Mulder,

Kemp, R., Hayward, P., Applewhaite, G., Everitt, B., & David, C. L., (2010). Treatment adherence therapy in people with

A. (1996). Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: psychotic disorders: Randomised controlled trial. British

Randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 312, Journal of Psychiatry, 197, 448–455.

345–349. Tsang, H. W., & Wong, T. K. S. (2005). The effects of a com-

Kemp, R., Kirov, G., Everitt, B., Hayward, P., & David, A. (1998). pliance therapy programme on Chinese male patients

Randomised controlled trial of compliance therapy: 18-month with schizophrenia. Asian Journal of Nursing Studies, 8,

follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 413–419. 47–61.

Downloaded from isp.sagepub.com at Hamad Medical Corporation on April 3, 2014

View publication stats

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Nadi Literally MeansDocument9 pagesNadi Literally MeansThomas DürstPas encore d'évaluation

- Recurrent Gingival Cyst of Adult: A Rare Case Report With Review of LiteratureDocument5 pagesRecurrent Gingival Cyst of Adult: A Rare Case Report With Review of Literaturesayantan karmakarPas encore d'évaluation

- Headache History Checklist For PhysiciansDocument3 pagesHeadache History Checklist For PhysiciansFarazPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Lower Blood Pressure QuicklyDocument38 pagesHow To Lower Blood Pressure QuicklyKay OlokoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric Caseheet PDFDocument23 pagesPediatric Caseheet PDFAparna DeviPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Antimicrobial Activity of Cassia Fistula and Flacoartia Indica Leaves.Document5 pagesAssessment of Antimicrobial Activity of Cassia Fistula and Flacoartia Indica Leaves.Eliana CaraballoPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Hypnosis in The Treatment of P... Flashes - A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument17 pagesClinical Hypnosis in The Treatment of P... Flashes - A Randomized Controlled TrialRIJANTOPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Intravascular Devices To Prevent Infection: LinicalDocument5 pagesManagement of Intravascular Devices To Prevent Infection: LinicalCristianMedranoVargasPas encore d'évaluation

- Minutes Prac Meeting 26 29 October 2020 - enDocument80 pagesMinutes Prac Meeting 26 29 October 2020 - enAmany HagagePas encore d'évaluation

- Fluoride: Nature's Cavity FighterDocument11 pagesFluoride: Nature's Cavity FighterAya OsamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Barack Huessein Obama Is The Most Dangerous Man To Ever LiveDocument3 pagesBarack Huessein Obama Is The Most Dangerous Man To Ever LivetravisdannPas encore d'évaluation

- Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities ofDocument6 pagesAntibacterial and Antifungal Activities ofSamiantara DotsPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015 Lifeguard Candidate PacketDocument12 pages2015 Lifeguard Candidate PacketMichelle BreidenbachPas encore d'évaluation

- Drugs & Cosmetics ActDocument70 pagesDrugs & Cosmetics ActAnonymous ibmeej9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kathon CG MsdsDocument9 pagesKathon CG MsdsKhairil MahpolPas encore d'évaluation

- IsolationDocument5 pagesIsolationapi-392611220Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pathophysiology Tia VS CvaDocument6 pagesPathophysiology Tia VS CvaRobby Nur Zam ZamPas encore d'évaluation

- Daily sales and expense recordsDocument29 pagesDaily sales and expense recordselsa fanny vasquez cepedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shatavari (Asparagus Racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia Reticulata) and Methi (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum) : The Herbal Galactogogues For RuminantsDocument7 pagesShatavari (Asparagus Racemosus), Jivanti (Leptadenia Reticulata) and Methi (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum) : The Herbal Galactogogues For RuminantsSanjay C. ParmarPas encore d'évaluation

- TESCTflyer 2012Document11 pagesTESCTflyer 2012Marco TraubPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardiovascular SystemDocument10 pagesCardiovascular SystemitsmesuvekshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug Study HazDocument7 pagesDrug Study HazRichard HazPas encore d'évaluation

- ACCIDENT REPORTING AND INVESTIGATION PROCEDUREDocument23 pagesACCIDENT REPORTING AND INVESTIGATION PROCEDUREkirandevi1981Pas encore d'évaluation

- Treatment of Pemphigus Vulgaris and Pemphigus FoliaceusDocument13 pagesTreatment of Pemphigus Vulgaris and Pemphigus FoliaceusMelly MayasariPas encore d'évaluation

- 2322 Part B DCHB IndoreDocument278 pages2322 Part B DCHB Indoreksanjay209Pas encore d'évaluation

- Erasme Igitabo Cy' Imiti Ivura Abantu Yo Mu Ibyaremwe 2Document105 pagesErasme Igitabo Cy' Imiti Ivura Abantu Yo Mu Ibyaremwe 2gashesabiPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Siop Lesson Plan Name: Marla Leland Content Area: Science Grade Level: 4 Grade (New Standards) English LearnersDocument13 pagesFinal Siop Lesson Plan Name: Marla Leland Content Area: Science Grade Level: 4 Grade (New Standards) English Learnersapi-285366742Pas encore d'évaluation

- School Form 8 (SF 8)Document2 pagesSchool Form 8 (SF 8)Met Malayo0% (1)

- Malaysia's Healthcare Industry Faces Economic ChallengesDocument10 pagesMalaysia's Healthcare Industry Faces Economic ChallengesAhmad SidqiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Background: (Budget 2016: Chapter 5 - An Inclusive and Fair Canada, 2021)Document4 pagesResearch Background: (Budget 2016: Chapter 5 - An Inclusive and Fair Canada, 2021)Talha NaseemPas encore d'évaluation