Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Anti Tpo Vs Pregnancy

Transféré par

neel721507Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Anti Tpo Vs Pregnancy

Transféré par

neel721507Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Original Article

Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 Received: August 23, 2011

Accepted after revision: September 3, 2012

DOI: 10.1159/000343759

Published online: November 10, 2012

Reduction of Miscarriages through

Universal Screening and Treatment of

Thyroid Autoimmune Diseases

Thibault Lepoutre a Frederic Debiève b Damien Gruson a Chantal Daumerie a

Departments of a Endocrinology and b Obstetrics, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de

Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

Key Words group after the 20th week (p ! 0.05). Conclusions: Our study

Miscarriage ⴢ Pregnancy ⴢ Thyroxine treatment ⴢ supports the potential benefit of universal screening and

Thyroid peroxidase antibodies ⴢ Universal screening L-T4 treatment for autoimmune thyroid disease during preg-

nancy. Efforts are still needed to further decrease miscar-

riage rates. Copyright © 2012 S. Karger AG, Basel

Abstract

Background/Aims: Universal screening for thyroid diseases

during pregnancy is controversial. Targeted screening does

not identify all women with thyroid dysfunction. Further- Introduction

more, antithyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAb) are sus-

pected to be associated with an increased risk of fetal loss, Pregnancy represents a major challenge for the thyroid

premature delivery and hypothyroidism. The aim of our gland, contributing to thyroid dysfunction in cases where

study was to assess the rationale behind universal screening the thyroid fails or is less able to adapt adequately to preg-

and propose thyroxine treatment in particular cases. Meth- nancy-related changes [1]. In the absence of iodine defi-

ods: Between January 2008 and May 2009, 537 consecutive ciency, hypothyroidism is often secondary to thyroid au-

iodine-supplemented women with a singleton pregnancy toimmunity, being associated with infertility [2], obstet-

[441 TPOAb– controls and 96 TPOAb+ women (47 nontreat- rical and fetal complications [3–6] and impaired

ed and 49 treated)] were evaluated using thyroid and obstet- neuropsychological development in children [7]. In a re-

ric parameters. According to our algorithm for thyroid cent randomized trial conducted by Lazarus et al. [8],

screening in pregnancy, if thyroid-stimulating hormone there was no preventive effect of antenatal screening and

(TSH) exceeded 1 mU/l in TPOAb+ women, 50 g of levothy- hypothyroidism treatment (at a gestational age of 12

roxine (L-T4) was prescribed. Results: The miscarriage rate weeks) on the intelligence quotient of 3-year-old children.

was significantly higher in the nontreated TPOAb+ group Thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAb) are detected

compared with the treated group (16 vs. 0%; p = 0.02). Com- in 10% of pregnant women. Several studies have showed

pared to the control group, TSH in TPOAb+ patients was

higher at the first prenatal visit prior to L-T4 treatment (p ! This paper was presented as a poster at the 14th International Thy-

0.01), while free thyroxine was higher than in the control roid Congress, Paris, France, in September 2010.

© 2012 S. Karger AG, Basel Chantal Daumerie

0378–7346/12/0744–0265$38.00/0 Endocrinology Department, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc

Fax +41 61 306 12 34 Université Catholique de Louvain, Avenue Hippocrate, 10

E-Mail karger@karger.ch Accessible online at: BE–1200 Brussels (Belgium)

www.karger.com www.karger.com/goi E-Mail chantal.daumerie @ uclouvain.be

a positive association between TPOAb and miscarriage May 2009. The study was approved by the ethical committee.

[9, 10], maternal hypothyroidism [11], preterm delivery Thyroid function parameters, namely TSH, free thyroxine (fT4)

and TPOAb, were assessed at the first prenatal visit during the

[12, 13], postpartum thyroiditis [14], maternal morbidity first trimester. The exclusion criteria were TSH values above the

in later life [15] and impaired neuropsychological devel- reference range (13.5 mU/l) at the first prenatal visit, L-T4 treat-

opment in children [16–18]. In 2006, Negro et al. [19] ment starting before the onset of pregnancy, Basedow disease,

demonstrated a significant decrease in miscarriage thyroidectomy, other serious diseases that could influence thy-

(–75%) and premature delivery (–69%) rates in TPOAb+ roid hormone levels (i.e. diabetes mellitus, HIV immunization

and cirrhosis) and therapeutic abortion. Figure 1 shows the dis-

women treated with levothyroxine (L-T4) compared with tribution of screened patients. Overall, 96 TPOAb+ women were

the nontreated group. Due to the lack of intervention included in the analysis; 49 were treated at the first prenatal visit

studies, the Endocrine Society’s Clinical Practice Guide- (group 1) and 47 were not treated (group 2). Furthermore, 441

lines of 2007 [20] and, more recently, the American Thy- TPOAb– women (group 3) served as a control group. All patients

roid Association [21] recommended targeted high-risk included were followed until delivery and received vitamin sup-

plements containing 150 g of potassium iodide/day.

case finding to identify women with thyroid dysfunction.

However, Vaidya et al. [22] revealed the limitations of tar- Laboratory Methods

geted screening, which overlooked one third of pregnant TSH, fT4 and TPOAb titers were measured using automated

women with hypothyroidism. Likewise, Horacek et al. immunoassays with chemiluminescence detection (DxI 800 Ac-

[23] recently reported the benefit of universal screening, cess, Beckman Coulter, USA). The hospital laboratory reference

values were 0.2–3.5 mU/l for TSH, 0.6–1.4 ng/dl for fT4 and !9

which detected twice as many thyroid disorders as tar- U/ml for TPOAb. Coefficients of variation were 10.62, 4.96, 4.55

geted high-risk case finding. In 2010, in a study com- and 3.72% for the TSH assay at concentrations of 0.027, 1, 8.18 and

paring the ability of universal and targeted screening to 28.59 mU/l, respectively, and 7.42, 3.28 and 4.56% for the fT4 as-

detect thyroid hormonal dysfunction, Negro et al. [24] say at concentrations of 0.47, 1.21 and 4.3 ng/dl, respectively. For

showed no significant differences between these two the TPOAb assay, the coefficient of variation was !12% at a con-

centration of 60.6 IU/ml.

screening strategies. Nonetheless, the question arises as

to whether it is acceptable to leave maternal thyroid dis- Obstetric Complications

ease undiagnosed. In 2009, a study conducted by Debiève Obstetric complications were classified into three groups. The

et al. [25] proposed treating TPOAb+ women with L-T4 first group involved miscarriages during the first trimester (^13

substitution if the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) weeks). The second group of complications included delivery

complications, notably preterm delivery (!37 weeks of gestation),

levels were higher than 1 mU/l. neonatal hypotrophy, cesarean section, placental abruption and

In this study, we assess whether universal thyroid delivery hemorrhage. The third group comprised various medical

screening should be undertaken in all pregnant women, conditions, namely pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclamp-

with L-T4 treatment being implemented in particular sia and gestational diabetes. Gestational hypertension was de-

cases, and if early L-T4 treatment could decrease the mis- fined as blood pressure 1140/90 mm Hg. Preeclampsia was diag-

nosed according to the criteria of the American College of Obste-

carriage rate in TPOAb+ women. tricians and Gynecologists and the National High Blood Pressure

Education Program. Gestational diabetes was defined as two or

more abnormal values on the oral glucose tolerance test. The dis-

Subjects and Methods tribution of TSH, fT4 and TPOAb levels was studied at different

time points during pregnancy, namely at ^10, 12, 15, 20, 30 and

Patients and Design 35 weeks.

Thyroid screening of pregnant women based on TSH and

TPOAb values was introduced at our institution in 2004. A dose Statistics

of 50 g of L-T4 is prescribed if TSH levels are higher than 1 mU/l Statistical analysis was performed using the MedCalc 7.2.1.0

and the TPOAb titer is positive [25] (19 U/ml) at the first prenatal package (Medcalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). For obstetric

visit. This TSH value of 1 mU/l was arbitrarily chosen based ini- complications, categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s

tially on results of Glinoer et al. [26] and then on our own. This exact test owing to the low number of observations. 2 or Fisher’s

study showed that mean TSH levels during the first and, to a less- exact test were used to compare patient characteristics. For con-

er extent, second trimester never exceeded 1 mU/l. These data tinuous variables, an analysis of variance test was used. When the

were confirmed by our own clinical experience [25]. TSH values distribution was found to be abnormal, data were logarithmically

were monitored and L-T4 replacement therapy adjusted in order transformed. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the

to achieve TSH levels between 1 and 2 mU/l. relationship between certain patient characteristics (i.e. age, TSH,

Our descriptive study retrospectively reviewed the files of 823 TPOAb titer, maternal weight and weight gain) and the occur-

consecutive iodine-supplemented women with a singleton preg- rence of miscarriage. A p value of !0.05 was considered signifi-

nancy who attended the prenatal clinic at the Cliniques Universi- cant.

taires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium, between January 2008 and

266 Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 Lepoutre /Debiève /Gruson /Daumerie

n = 823

189 TPOAb+ 634 TPOAb–

93 excluded 193 excluded

96 TPOAb+

49 T at 1st prenatal visit 47 NT 441 controls

(group 1) (group 2) (group 3)

Fig. 1. Flow chart of patients screened for thyroid tests. Patients group for the following reasons: 33 for L-T4 treatment started be-

were excluded from the control group for the following reasons: fore the onset of pregnancy; 7 for Basedow disease; 20 for hypo-

55 for thyroid dysfunction history or previous L-T4 treatment; 62 thyroidism at the first prenatal visit; 19 missing during pregnan-

missing during pregnancy and 16 with incomplete data; 10 for cy and 1 with incomplete data; 1 for HIV immunization; 4 for

medical abortions; 5 for hypothyroidism (13.5 mU/l) at the first multiple pregnancies, and 8 were working members. First trimes-

prenatal visit; 5 for serious diseases (diabetes mellitus, HIV im- ter screening (and treatment) rate: 34/49 (69%) for group 1, 31/47

munization or cirrhosis); 12 for multiple pregnancies, and 28 were (66%) for group 2 and 311/441 (71%) for group 3. T = Treated;

working members. Patients were excluded from the TPOAb+ NT = nontreated.

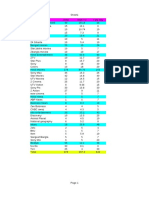

Results Table 1. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women in the differ-

ent groups

The clinical characteristics of the patients at the first

Clinical Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 p

prenatal visit are shown in table 1. No significant differ- characteristics (n = 49) (n = 47) (n = 441) value

ences were observed between the groups (p 1 0.05).

Screening and treatment rates during the first trimester Maternal age, years 31.585.5 32.585.3 31.985.1 0.6

were 69% in group 1 [34/49; 82% (28/34) at ^10 weeks], Maternal weight, kg 63810.4 61.3812.5 62.9811.7 0.5

66% (31/47) in group 2 (p = 0.83 compared with group 1, Weight gain, kg 13.386 12.884.7 1485.6 0.7

Primigravidity, % 32.7 25.5 28.8 0.7

Fisher’s exact test) and 71% (311/441) in the control group. Obstetrical history, % 28.6 42.6 34 0.3

Patients who were not screened during first trimester, Infertility, % 16.3 8.5 8.6 >0.1

and thus did not receive treatment for group 1, were not

considered in the analysis of the miscarriage rate. The Values are given as means 8 SD or percentages. Primigravidity

numbers of studied patients were 34, 31 and 311 for groups was defined as first-time pregnancy. Obstetrical history was consid-

ered positive if the difference between the gravidity and parity was

1, 2 and 3, respectively (fig. 1). The initial L-T4 dose in higher than 1. 2 test was used for comparison of primigravidity and

group 1, started as soon as TPOAb was detected and TSH obstetrical history and Fisher’s exact test between groups for com-

was 11 mU/l, remained unchanged throughout the preg- parison of infertility. An analysis of variance test was used for con-

nancy in 88% of patients (43/49). In order to reach and tinuous variables (maternal age, weight and weight gain).

maintain a TSH level between 1 and 2 mU/l, the L-T4 dose

was increased in 4 patients, while the dose was decreased

in 2 due to TSH !1 mU/l.

group and the nontreated group (group 2; 5/31; p = 0.02).

Obstetric Complications Four of these 5 nontreated TPOAb+ women with early

Among group 1 patients with TPOAb+ who were miscarriage had TSH values above 1 mU/l. The control

treated at the first prenatal visit there were no cases of group (group 3) had a miscarriage rate of 8% (25/311),

miscarriage (table 2a). A significant difference of 16% which was similar to that of the nontreated TPOAb+

was observed in the miscarriage rates between this patients (group 2). No other significant differences re-

Reduction of Miscarriages through Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 267

Universal Thyroid Screening

Table 2. Obstetric complications in the treated TPOAb+ group (group 1) versus the nontreated TPOAb+ group (group 2) and in the

nontreated TPOAb+ group (group 2) versus controls (group 3)

a Miscarriage

TPOAb+ TPOAb– p value

group 1 (n = 34) group 2 (n = 31) group 3 (n = 311) group 1 vs. 2 group 3 vs. 2

Miscarriage, n 0 (0) 5 (16.1) 25 (8) 0.02 0.17

b Delivery complications and gestational hypertension/diabetes

TPOAb+ TPOAb– p value

group 1 (n = 49) group 2 (n = 47) group 3 (n = 441) group 1 vs. 2 group 3 vs. 2

Delivery complications, n

Preterm delivery 3 (6.1) 4 (10) 29 (7.2) 0.69 0.52

Neonatal hypotrophy 2 (4.1) 0 (0) 5 (1.2) 0.5 1

Cesarean section 8 (16.3) 8 (20) 94 (23.3) 0.78 0.84

Placental abruption 1 (2) 0 (0) 2 (0.5) 1 1

Delivery hemorrhage 0 (0) 2 (5) 7 (1.7) 0.2 0.19

14 (26.5) 14 (22.5) 137 (28.8) 0.81 0.47

Gestational hypertension/diabetes, n

Hypertension 1 (2) 2 (5) 13 (3.2) 0.59 0.64

Preeclampsia 1 (2) 2 (5) 8 (2) 0.59 0.23

Gestational diabetes 2 (4.1) 1 (2.5) 7 (1.7) 1 0.53

4 (8.2) 5 (12.5) 28 (6.2) 0.73 0.17

Numbers in parentheses represent percentages, and totals are a percentage of the different patients with (at least) one obstetric

complication.

lating to delivery and medical conditions, such as ges- baseline values. From week 20 onwards, fT4 values in the

tational hypertension or diabetes, were observed (ta- control group differed significantly from those in the

ble 2b). treated group (0.75 8 0.09 vs. 0.68 8 0.12 ng/dl, 0.72 8

0.1 vs. 0.62 8 0.08 ng/dl, and 0.74 8 0.1 vs. 0.63 8 0.09

Evolution of Thyroid Function Tests ng/dl at 20, 30 and 35 weeks, respectively; p ! 0.05).

Figure 2 illustrates the TSH and fT4 levels at different TPOAb titers were 2–3 times higher in the treated group

time points throughout pregnancy for groups 1 (treated compared with the nontreated group throughout preg-

at the first prenatal visit), 2 (nontreated) and 3 (control). nancy. Lastly, antibody levels decreased by 65–70% be-

At baseline prior to L-T4 treatment, mean TSH values tween the first trimester and 9th month of pregnancy.

were significantly higher in the treated group compared

with the control group (1.61 8 0.77 vs. 1.05 8 0.7 mU/l;

p = 0.005). After initiating L-T4 therapy, TSH values de- Discussion

creased and then remained stable. No other difference

was subsequently found. Despite higher values in the Our study evaluated the rationale behind universal

nontreated group, fT4 distribution did not reveal any sig- thyroid function screening in women and the potential

nificant differences at baseline. Appropriate L-T4 substi- benefits of thyroxine treatment in particular cases during

tution resulted in stable fT4 values in the treated group early pregnancy. The analysis of obstetric complications

during pregnancy. In contrast, in the two other groups revealed a significant difference in miscarriage rates in

(nontreated and control), fT4 decreased in relation to TPOAb+ women treated at the first prenatal visit (group

268 Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 Lepoutre /Debiève /Gruson /Daumerie

a

2.5

2.0

1.5 1

1.0

0.5

0

2.5

TSH (mU/l)

2.0

Groups

1.5 2

1.0

0.5

0

2.5

2.0

1.5 3

1.0

0.5

0

≤10 15 20 30 35 40

a Time of pregnancy (weeks)

1.25

1.00 b

a a

1

0.75

0.50

1.25

fT4 (ng/dl)

1.00

Groups

2

0.75

0.50

1.25

1.00

3

Fig. 2. Distribution of TSH (a) and fT4 lev- 0.75

els (b) at different time points during preg-

nancy. Continuous lines represent the 0.50

mean, and the box plots represent the first ≤10 15 20 30 35 40

quartile, median and third quartile. a p ! b Time of pregnancy (weeks)

0.05: group 1 vs. group 3; b p ! 0.05: group

1 vs. groups 2 and 3.

1) as compared with the nontreated group (group 2), with The impact of TPOAb levels on miscarriage rates is

no miscarriages being observed in the treated TPOAb+ controversial. The studies of Iijima et al. [27] and Stagna-

women. In contrast, 4 TPOAb+ women with a TSH value ro-Green et al. [9] did not find any correlation between

11 mU/l had an early miscarriage before initiating L-T4 these two parameters. In contrast, another study report-

therapy. ed higher TPOAb titers in women with miscarriage com-

Reduction of Miscarriages through Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 269

Universal Thyroid Screening

Table 3. Differences in age and TSH levels in TPOAb+ women compared to TPOAb– women, in studies on the association between

thyroid autoimmunity and miscarriage

TPOAb+ women TPOAb– women Difference p

Age, years

Bussen and Steck [41] 3185.2 30.384.5 +0.7 NS

Bagis et al. [42] 27.786.2 25.985.2 +1.8 <0.0009

Glinoer et al. [43] 29.381 27.382 +2 <0.001

Lejeune et al. [44] 28.289.5 27.286.8 +1 0.06

Pratt et al. [45] 3382.9 3483.4 –1 NS

Iijima et al. [27] 30.284.8 3084.3 +0.2 NS

Muller et al. [46] 32.483.3 32.484.4 0 NS

Rushworth et al. [47] 34 (20–41) 34 (22–46) 0 NS

Poppe et al. [48] 33.284.6 31.685.4 +1.6 NS

Poppe et al. [49] 3382.9 3483.4 –1 NS

Kim et al. [50] 34.386.4 31.286.7 +3.1 NS

Present study 31.585.5 31.985.1 –0.4 NS

TSH, mU/l

Stagnaro-Green et al. [9] 2.35 1.6 0.75 0.12

Glinoer et al. [43] 1.4 0.9 0.5 <0.01

Muller et al. [46] 3.583.6 1.780.9 1.8 <0.005

Bagis et al. [42] 1.8681.8 1.1780.9 0.69 <0.001

Poppe et al. [48] 1.6 (0.02–4.1) 1.3 (0.05–3.6) 0.3 NS

Mecacci et al. [51] 3.62 1.29 2.33 0.009

Present study 1.6180.77 1.0580.7 0.56 0.005

Values are shown as means 8 SD or medians (range). NS = Not significant.

pared to those without [28]. Recent meta-analyses have hibited TSH values similar to those of the control group.

emphasized the association between the presence of au- Based on our algorithm, women with TSH values !1

toimmune thyroid antibodies and pregnancy outcomes mU/l were not offered any treatment. In our population,

[10, 29]. Mild thyroid failure or decreased capacity to fT4 levels were lower than in previous studies [31], which

modify thyroid hormones appeared to play a predomi- may be accounted for by the slight iodine deficiency in

nant role. As summarized in table 3, in our population the Belgian population [32].

the mean TSH levels were significantly higher in women Another important parameter to consider is the nor-

with TPOAb+ before LT-4 treatment (group 1; 1.61 8 mal TSH cutoff value in pregnant TPOAb– women. Ne-

0.77 vs. 1.05 8 0.7 mU/l in the TPOAb– group; p = 0.005). gro et al. [33] found an increased pregnancy loss during

Another important finding to consider is age, as we know the first trimester in women with TSH values between 2.5

that greater maternal age is a risk factor for miscarriage. and 5 mU/l compared to women with TSH ^2.5 mU/l.

Most of the studies reported a slightly greater age in These results support revising the established cutoff of

TPOAb+ women (table 3). However, despite a trend to- ‘normal’ TSH in pregnant women up to 2.5 mU/l.

ward higher age and TSH levels in patients with miscar- Although universal thyroid screening is not totally ac-

riage, parameters such as age, TSH, TPOAb titer and ma- cepted, several studies in favor of universal screening

ternal weight were not significantly associated with this demonstrated the potential consequences of thyroid dys-

observation, probably because of the low number of pa- function on maternal and fetal health as well as the ben-

tients who miscarriage in the TPOAb+ group. eficial effects of thyroxine treatment [2–19, 22, 23]. De-

Our results, along with those of Negro et al. [19], con- spite finding no significant decrease in obstetric compli-

firmed the beneficial effects of L-T4 substitution, as re- cations with universal screening and case finding, the

flected by the decreased miscarriage and premature de- results of Negro et al. [24] showed fewer obstetric compli-

livery rates in TPOAb+ women treated with low-dose cations in the low-risk group identified by universal

L-T4 [30]. In our study, nontreated TPOAb+ women ex- screening and benefiting from hypo-/hyperthyroidism

270 Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 Lepoutre /Debiève /Gruson /Daumerie

treatment, thus providing strong evidence that universal A longitudinal study involving normal TPOAb and

screening for TPOAb and TSH in pregnant women iodine-supplemented women should be performed in or-

should be considered [34]. Moreover, the first study eval- der to establish the gestational age-specific reference in-

uating the cost-effectiveness of screening all pregnant tervals for TSH and fT4 and better adapt possible L-T4

women for autoimmune thyroid disease during the first treatments for TPOAb+ pregnant women.

trimester demonstrated a cost-saving result compared

with no screening [35].

Despite a lack of consensus among professional or- Conclusions

ganization guidelines regarding thyroid dysfunction

screening, a survey conducted in Maine, USA, showed Our study supports the potential benefit of early uni-

that many practitioners have already implemented rou- versal thyroid screening, as L-T4 treatment for TPOAb+

tine TSH testing in pregnant women [36]. Recently, a pregnant women who were diagnosed via universal

European survey found similar results, with 42% of re- screening appeared to reduce miscarriage rates. Further-

sponders screening all pregnant women for thyroid dys- more, L-T4 therapy was offered to women with TPOAb+

function [37]. Klubo-Gwiezdzinska et al. [38] clearly and TSH values 11 mU/l. To further decrease miscarriage

demonstrated the necessity of updating and promul- rates, efforts are still required to conduct universal thy-

gating new guidelines for L-T4 treatment during preg- roid screening prior to pregnancy or as soon as pregnan-

nancy. cy is confirmed. Optimal cooperation and communica-

The distinctiveness of this present study is its use of an tion between endocrinologists and obstetricians is also

algorithm, which has been employed at our institution necessary. Ideally, randomized placebo-controlled stud-

since 2004, allowing us to highlight the benefits and dif- ies are needed in order to confirm the potential benefits

ficulties of universal screening and treatment of autoim- of universal screening and treatment of autoimmune thy-

mune thyroid diseases. In spite of our algorithm, the dif- roid disease during pregnancy.

ferences observed in the incidence of miscarriages in the

two TPOAb+ groups reflect the difficulties inherent in

early pregnancy screening. For this reason, we suggest Acknowledgments

conducting screening prior to pregnancy rather than at

We would like to thank Prof. Pierre Bernard and Corinne Hu-

6–7 weeks in order to reduce the incidence of miscarriage

binont from the Obstetrics Department and Prof. Marie-Fran-

in TPOAb+ women. Improved cooperation and commu- çoise Vincent from the Medical Biochemistry Department for

nication between endocrinologists and obstetricians in their collaboration and providing the medical records. We also

addition to an increased awareness about the risks of thy- acknowledge the assistance of Prof. Annie Robert and Jean Cumps

roid dysfunction among the general population should be with the statistical analysis.

emphasized [39].

One of the strengths of our study is its concern for the

real-life treatment of patients, which helped to highlight

some of the erroneous parts of our algorithm. In addition, References 1 Glinoer D: The regulation of thyroid func-

tion in pregnancy: pathways of endocrine

a wide range of parameters for obstetric complications adaptation from physiology to pathology.

were evaluated. To our knowledge, this is the first study Endocr Rev 1997;18:404–433.

evaluating the different aspects of universal screening 2 Poppe K, Velkeniers B, Glinoer D: The role

of thyroid autoimmunity in fertility and

and autoimmune thyroid disease treatment in daily clin- pregnancy. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab

ical practice. One limitation of this retrospective study 2008;4:394–405.

with a descriptive design was the lack of comparisons 3 Abalovich M, Gutierrez S, Alcaraz G, Mac-

callini G, Garcia A, Levalle O: Overt and

with another form of screening (e.g. case finding). Other subclinical hypothyroidism complicating

limitations include the cross-sectional analysis of TSH pregnancy. Thyroid 2002;12:63–68.

and fT4 distribution, use of nonspecific reference values 4 Casey BM, Dashe JS, Wells CE, McIntire DD,

Byrd W, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG: Sub-

for pregnancy in the algorithm and the absence of certain clinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy out-

variables, such as socioeconomic status, body mass index comes. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:239–245.

and patient ethnicity, as significant differences relating to

ethnicity are found for specific reference intervals for

thyroid function tests [40].

Reduction of Miscarriages through Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 271

Universal Thyroid Screening

5 Allan WC, Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Wil- 17 Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, Verkerk G, 28 Wilson R, Ling H, MacLean MA, Mooney J,

liams JR, Mitchell ML, Hermos RJ, Faix JD, van Son MM, de Vijlder JJ, Vulsma T, Kinnane D, McKillop JH, Walker JJ: Thyroid

Klein RZ: Maternal thyroid deficiency and Wiersinga WM, Drexhage HA, Vader HL: antibody titer and avidity in patients with re-

pregnancy complications: implications for Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations current miscarriage. Fertil Steril 1999; 71:

population screening. J Med Screen 2000; 7: during early pregnancy are associated with 568–561.

127–130. impaired psychomotor development in infan- 29 Thangaratinam S, Tan A, Know E, Kilby

6 Leung AS, Millar LK, Koonings PP, Montoro cy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;50:149–155. MD, Franklyn J, Coomarasamy A: Associa-

M, Mestman JH: Perinatal outcome in hypo- 18 Li Y, Shan Z, Teng W, Yu X, Li Y, Fan C, Teng tion between thyroid autoantibodies and

thyroid pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1993; X, Guo R, Wang H, Li J, Chen Y, Wang W, miscarriage and preterm birth: meta-analy-

81:349–353. Chawinga M, Zhang L, Yang L, Zhao Y, Hua sis of evidence. BMJ 2011;342:d2616.

7 Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, Wil- T: Abnormalities of maternal thyroid func- 30 Glinoer D: Miscarriage in women with posi-

liams JR, Knight GJ, Gagnon J, O’Heir CE, tion during pregnancy affect neuropsycho- tive anti-TPO antibodies: is thyroxine the

Mitchell ML, Hermos RJ, Waisbren SE, Faix logical development of their children at 25– answer? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:

JD, Klein RZ: Maternal thyroid deficiency 30 months. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010; 72: 2500–2502.

during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsy- 825–829. 31 Stricker R, Echenard M, Eberhart R, Che-

chological development of the child. N Engl 19 Negro R, Formoso G, Mangieri T, Pezzarossa vailler MC, Perez V, Quinn FA, Stricker R:

J Med 1999;341:549–555. A, Dazzi D, Hassan H: Levothyroxine treat- Evaluation of maternal thyroid function

8 Lazarus JH, Bestwick JP, Channon S, Para- ment in euthyroid pregnant women with au- during pregnancy: the importance of using

dice R, Maina A, Rees R, Chiusano E, John toimmune thyroid disease: effects on obstet- gestational age-specific reference intervals.

R, Guaraldo V: Antenatal thyroid screening rical complications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab Eur J Endocrinol 2007;157:509–514.

and childhood cognitive function. N Engl J 2006;91:2587–2591. 32 World Health Organization: Iodine defi-

Med 2012;366:493–501. 20 Abalovich M, Amino N, Barbour LA, Cobin ciency in Europe: A continuing health prob-

9 Stagnaro-Green A, Roman SH, Cobin RH, RH, De Groot LJ, Glinoer D, Mandel SJ, lem. Geneva, 2007.

el-Harazy E, Alvarez-Marfany M, Davies TF: Stagnaro-Green A: Management of thyroid 33 Negro R, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, Tinelli A,

Detection of at risk pregnancy using highly dysfunction during pregnancy and postpar- Mangieri T, Stagnaro-Green A: Increased

sensitive assays for thyroid autoantibodies. tum: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice pregnancy loss rate in thyroid antibody neg-

JAMA 1990;264:1422–1425. Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; ative women with TSH levels between 2.5

10 Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM: Thyroid au- 92:S1–S47. and 5.0 in the first trimester of pregnancy. J

toimmunity and miscarriage. Eur J Endocri- 21 Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:E44–E48.

nol 2004; 150:751–755. E, Azizi F, Mestman J, Negro R, Nixon A, 34 Alexander EK: Here’s to you, baby! A step

11 Glinoer D, Riahi M, Grün JP, Kinthaert J: Pearce EN, Soldin OP, Sullivan S, Wiersinga forward in support of universal screening of

Risk of subclinical hypothyroidism in preg- W: Guidelines of the American Thyroid As- thyroid function during pregnancy. J Clin

nant women with asymptomatic autoim- sociation for the diagnosis and management Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:1575–1577.

mune thyroid disorders. J Clin Endocrinol of thyroid disease during pregnancy and 35 Dosiou C, Sanders GD, Araki SS, Crapo LM:

Metab 1994;79:197–204. postpartum. Thyroid 2011;21:1081–1125. Screening pregnant women for autoimmune

12 Stagnaro-Green A: Maternal thyroid disease 22 Vaidya B, Anthony S, Bilous M, Shields B, thyroid disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis.

and preterm delivery. J Clin Endocrinol Drury J, Hutchison S, Bilous R: Detection of Eur J Endocrinol 2008;158:841–851.

Metab 2009;94:21–25. thyroid dysfunction in early pregnancy: uni- 36 Haddow JE, McClain MR, Palomaki GE,

13 Negro R, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, Tinelli A, versal screening or targeted high-risk case Kloza EM, Williams J: Screening for thyroid

Mangieri T, Stagnaro-Green A: Thyroid an- finding? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92: disorders during pregnancy: results of a sur-

tibody positivity in the first trimester of 203–207. vey in Maine. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;

pregnancy is associated with negative preg- 23 Horacek J, Spitalnikova S, Dlabalova B, 194:471–474.

nancy outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab Malirova E, Vizda J, Svilias I, Cepkova J, Mc 37 Vaidya B, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Laur-

2011;96:E920–E924. Grath C, Maly J: Universal screening detects berg P, Negro R, Vermiglio F, Poppe K: Treat-

14 Premawardhana LD, Parkes AB, John R, two-times more thyroid disorders in early ment and screening of hypothyroidism in

Harris B, Lazarus JH: Thyroid peroxidase pregnancy than targeted high-risk case find- pregnancy: results of a European survey. Eur

antibodies in early pregnancy: utility for pre- ing. Eur J Endocrinol 2010;163:645–650. J Endocrinol 2012;166:49–54.

diction of postpartum thyroid dysfunction 24 Negro R, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, Tinelli A, 38 Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Burman KD, Van

and implications for screening. Thyroid Mangieri T, Stagnaro-Green A: Universal Nostrand D, Wartofsky L: Levothyroxine

2004;14:610–615. screening versus case finding for detection treatment in pregnancy: indications, effica-

15 Männistö T, Vääräsmäki M, Pouta A, Harti- and treatment of thyroid hormonal dysfunc- cy, and therapeutic regimen. J Thyroid Res

kainen AL, Ruokonen A, Surcel HM, Bloigu tion during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol 2011;2011:843591.

A, Järvelin MR, Suvanto E: Thyroid dysfunc- Metab 2010;95:1699–1707. 39 Glinoer D, Spencer CA: Serum TSH deter-

tion and autoantibodies during pregnancy as 25 Debiève F, Dulière S, Bernard P, Hubinont C, minations in pregnancy: how, when and

predictive factors of pregnancy complica- De Nayer P, Daumerie C: To treat or not to why? Nat Rev Endocrinol 2010;6:526–529.

tions and maternal morbidity in later life. J treat euthyroid autoimmune disorder during 40 La’ulu SL, Roberts WL: Ethnic differences in

Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:1084–1094. pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2009; 67: first-trimester thyroid reference intervals.

16 Pop VJ, de Vries E, van Baar AL, Waelkens 178–182. Clin Chem 2011;57:913–915.

JJ, de Rooy HA, Horsten M, Donkers MM, 26 Glinoer D, de Nayer P, Bourdoux P, Lemone 41 Bussen S, Steck T: Thyroid autoantibodies in

Komproe IH, van Son MM, Vader HL: Ma- M, Robyn C, van Steirteghem A, Kinthaert J, euthyroid non-pregnant women with recur-

ternal thyroid peroxidase antibodies during Lejeune B: Regulation of maternal thyroid rent spontaneous abortions. Hum Reprod

pregnancy: a marker of impaired child devel- during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;10:2938–2940.

opment? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80: 1990;71:276–287. 42 Bagis T, Gokcel A, Saygili ES: Autoimmune

3561–3566. 27 Iijima T, Tada H, Hidaka Y, Mitsuda N, Mu- thyroid disease in pregnancy and the post-

rata Y, Amino N: Effects of autoantibodies partum period: relationship to spontaneous

on the course of pregnancy and fetal growth. abortion. Thyroid 2001;11:1049–1053.

Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:364–369.

272 Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 Lepoutre /Debiève /Gruson /Daumerie

43 Glinoer D, Soto MF, Bourdoux P, Lejeune B, 46 Muller AF, Verhoeff A, Mantel MJ, Berghout 49 Poppe K, Glinoer D, Tournaye H, Schiette-

Delange F, Lemone M, Kinthaert J, Robijn C, A: Thyroid autoimmunity and abortion: a catte J, Devroey P, van Steirteghem A,

Grun JP, de Nayer P: Pregnancy in patients prospective study in women undergoing in Haentjens P, Velkeniers B: Impact of ovarian

with mild thyroid abnormalities: maternal vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 1999; 71: 30– hyperstimulation on thyroid function in

and neonatal repercussions. J Clin Endocri- 34. women with and without thyroid autoim-

nol Metab 1991;73:421–427. 47 Rushworth FH, Backos M, Rai R, Chilcott IT, munity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89:

44 Lejeune B, Grun JP, de Nayer P, Servais G, Baxter N, Regan L: Prospective pregnancy 3808–3812.

Glinoer D: Antithyroid antibodies underly- outcome in untreated recurrent miscarriers 50 Kim CH, Chae HD, Kang BM, Chang YS: In-

ing thyroid abnormalities and miscarriage with thyroid autoantibodies. Hum Reprod fluence of antithyroid antibodies in euthy-

or pregnancy induced hypertension. Br J Ob- 2000;15:1637–1639. roid women on in vitro fertilization-embryo

stet Gynaecol 1993;100:669–672. 48 Poppe K, Glinoer D, Tournaye H, Devroey transfer outcome. Am J Reprod Immunol

45 Pratt D, Novotny M, Kaberlein G, Dudkie- P, van Steirteghem A, Kaufman L, Velke- 1998;40:2–8.

wicz A, Gleicher N: Antithyroid antibodies niers B: Assisted reproduction and thyroid 51 Mecacci F, Parretti E, Cioni R, Lucchetti R,

and the association with non-organ-specific autoimmunity: an unfortunate combina- Magrini A, La Torre P, Mignosa M, Acanfora

antibodies in recurrent pregnancy loss. Am tion? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: L, Mello G: Thyroid autoimmunity and its

J Obstet Gynecol 1993;168:837–841. 4149–4152. association with non-organ-specific anti-

bodies and subclinical alterations of thyroid

function in women with a history of preg-

nancy loss or preeclampsia. J Reprod Immu-

nol 2000;46:39–50.

Reduction of Miscarriages through Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012;74:265–273 273

Universal Thyroid Screening

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Form of Last Pay-Certificate For High School (Aided) TeachersDocument1 pageForm of Last Pay-Certificate For High School (Aided) Teachersneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- PGED Part-I Paper-II Unit-4: Transfer of Learning: Concept and Types of Transfer Papiyaupadhyay@wbnsou - Ac.inDocument27 pagesPGED Part-I Paper-II Unit-4: Transfer of Learning: Concept and Types of Transfer Papiyaupadhyay@wbnsou - Ac.inneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Some Issues in Indian Education: PGED, P. I, U. 10Document19 pagesSome Issues in Indian Education: PGED, P. I, U. 10neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- No LiabilityDocument1 pageNo Liabilityneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Smartbut Order - 100055395Document1 pageSmartbut Order - 100055395neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Socialisation: The Meaning, Features, Types, Stages and ImportanceDocument39 pagesSocialisation: The Meaning, Features, Types, Stages and Importanceneel721507100% (1)

- Education - English June 2019Document8 pagesEducation - English June 2019sudip surPas encore d'évaluation

- Basaran 2013Document2 pagesBasaran 2013neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- JhargramDocument3 pagesJhargramneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- PGED - Reduced SyllabusDocument18 pagesPGED - Reduced Syllabusneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- NG CalciumDocument36 pagesNG CalciumSandeep ElluubhollPas encore d'évaluation

- WHO 2019 nCoV Clinical 2020.5 EngDocument62 pagesWHO 2019 nCoV Clinical 2020.5 EngTemis Edwin Guzman MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Ivermectin MedRxivDocument15 pagesIvermectin MedRxivneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Carbonyl ChemistryDocument63 pagesCarbonyl Chemistryelgendy1204100% (3)

- Aldol Condensation Reaction: Charles-Adolphe Wurtz in 1872Document11 pagesAldol Condensation Reaction: Charles-Adolphe Wurtz in 1872neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document17 pagesChapter 3neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aldol CondensationDocument18 pagesAldol CondensationAnurag Uniyal100% (1)

- CH307 Inorganic Kinetics: Dr. Andrea Erxleben Room C150 Andrea - Erxleben@nuigalway - IeDocument50 pagesCH307 Inorganic Kinetics: Dr. Andrea Erxleben Room C150 Andrea - Erxleben@nuigalway - Ieneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Publication 2 1424 1587Document12 pagesPublication 2 1424 1587neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Advanced Research: Muhammad Adnan Shereen, Suliman Khan, Abeer Kazmi, Nadia Bashir, Rabeea SiddiqueDocument8 pagesJournal of Advanced Research: Muhammad Adnan Shereen, Suliman Khan, Abeer Kazmi, Nadia Bashir, Rabeea SiddiqueAnmol YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 12 Mechanism of Reaction: Aldol CondensationDocument17 pagesChapter 12 Mechanism of Reaction: Aldol CondensationTiya KapoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Application For General Transfer SSCDocument3 pagesApplication For General Transfer SSCneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Form 16Document4 pagesForm 16neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- LSD-NEERI - Water Quality AnalysisDocument8 pagesLSD-NEERI - Water Quality Analysisneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- LSD-NEERI - Water Quality AnalysisDocument68 pagesLSD-NEERI - Water Quality AnalysisSubrahmanyan EdamanaPas encore d'évaluation

- ChannelDocument1 pageChannelneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Form 16Document4 pagesForm 16neel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bents RuleDocument1 pageBents Ruleneel721507Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Thyroid and HeartDocument6 pagesThyroid and HeartGaudeamus IgiturPas encore d'évaluation

- Blood TestsDocument3 pagesBlood TestsMarycharinelle Antolin MolinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hypothyroidism: Kommerien Daling, MD Chiefs Conference August 14th 2008Document50 pagesHypothyroidism: Kommerien Daling, MD Chiefs Conference August 14th 2008HaNy NejPas encore d'évaluation

- Essence 8th Edition ThyroidDocument22 pagesEssence 8th Edition ThyroidMohned AlhababiPas encore d'évaluation

- Control and CoordinationDocument22 pagesControl and CoordinationMozibor RahmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Thyroid WLNDocument36 pagesThyroid WLNEmmanuel MukukaPas encore d'évaluation

- MCQs Endo FinalDocument6 pagesMCQs Endo Finalhassan qureshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Thyroid Cancer: TNM ClassificationDocument2 pagesThyroid Cancer: TNM ClassificationEl FaroukPas encore d'évaluation

- Drugs Used For HypothyroidismDocument8 pagesDrugs Used For HypothyroidismBea SungaPas encore d'évaluation

- Life Sciences P2 Feb-March 2013 Version 1 Memo EngDocument9 pagesLife Sciences P2 Feb-March 2013 Version 1 Memo EngDrAzTikPas encore d'évaluation

- USMLE Vignette Flashcards: Micro, Path and Pharm - SidebysideDocument18 pagesUSMLE Vignette Flashcards: Micro, Path and Pharm - SidebysideMedSchoolStuffPas encore d'évaluation

- Infographic #3Document1 pageInfographic #3Trixia AlmendralPas encore d'évaluation

- Hyperthyroidism (Thyrotoxicosis) : 郑州大学第一附院内分泌科 王守俊 Wang shou junDocument133 pagesHyperthyroidism (Thyrotoxicosis) : 郑州大学第一附院内分泌科 王守俊 Wang shou junapi-19916399Pas encore d'évaluation

- ThyroidDocument21 pagesThyroidcombuter0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Optimizing Thyroid Medications Ebook-3Document133 pagesOptimizing Thyroid Medications Ebook-3martuca100% (1)

- 015 Physiology MCQ ACEM Primary EndocrineDocument11 pages015 Physiology MCQ ACEM Primary Endocrinesandesh100% (1)

- Special Laboratory and Diagnostic TestsDocument75 pagesSpecial Laboratory and Diagnostic TestskrismaevelPas encore d'évaluation

- Endocrine SystemDocument6 pagesEndocrine SystemChechan AmbaPas encore d'évaluation

- ThyroidDocument49 pagesThyroidAbeer RadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Thyroid Disorders During Pregnancy and A PDFDocument6 pagesThyroid Disorders During Pregnancy and A PDFtania jannah100% (1)

- Pharmacology in RehabilitationDocument682 pagesPharmacology in RehabilitationDiana Mesquita100% (1)

- MS Pooja Singh 35654232021 12 02 03 15 49 514 6 114 132829410136155712Document2 pagesMS Pooja Singh 35654232021 12 02 03 15 49 514 6 114 132829410136155712Lucky BoffinPas encore d'évaluation

- Hyperthyroid DisordersDocument49 pagesHyperthyroid Disordersayu permata dewiPas encore d'évaluation

- Thyroid DiseaseDocument30 pagesThyroid Diseasemy Lord JesusPas encore d'évaluation

- Mock2 9thmarch CompDocument41 pagesMock2 9thmarch CompObaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Chennai ThesisDocument22 pagesChennai ThesisShradhanjali PandaPas encore d'évaluation

- GordonsDocument10 pagesGordonsハニファ バランギPas encore d'évaluation

- Too Cold Too TiredDocument66 pagesToo Cold Too TiredPatricia Lawler75% (4)

- Thyroid Testing Using RaiDocument8 pagesThyroid Testing Using RaideblackaPas encore d'évaluation