Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Robbins Ob14 Im 15 PDF

Transféré par

Doni SujanaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Robbins Ob14 Im 15 PDF

Transféré par

Doni SujanaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

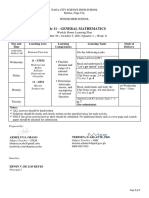

Chapter 15 Foundations of Organization Structure Page 488

Case Incident 1

Can A Structure Be Too Flat?

Steelmaker Nucor likes to think it has management figured out. And with good reason.

It is the darling of the business press. Its management practices are often

favorably reviewed in management texts. And it’s been effective by nearly any business

metric.

There’s one fundamental management practice that Nucor doesn’t appear to have

mastered: how to structure itself.

Nucor has always prided itself on having just three levels of management separating the

CEO from factory workers. With Nucor’s structure, plant managers report directly

to CEO Dan DiMicco. As Nucor continues to grow, though, DiMicco is finding it

increasingly hard to maintain this simple structure. So, in 2006 DiMicco added another

layer of management, creating a new layer of five executive vice presidents. “I needed to

be free to make decisions on trade battles,” he said.

Still, even with the new layer in its structure, Nucor is remarkably lean and simple. U.S.

Steel employs 1,200 people at its corporate headquarters, compared to a scant 66

at Nucor’s. At Nucor, managers still answer their own phone calls and e-mails, and the

firm has no corporate jet. Even companies as comparatively lean as Toyota appear fat

and complicated compared to Nucor. “You’re going to get at least ten layers at Toyota

before you get to the president,” says a former Toyota engineer.

Questions

1. How does the Nucor case illustrate the limitations of the simple organizational

structure?

Answer: With only a few layers of management, there is a wide span of control.

As Nucor grows, this structure may prove inadequate due to information

overload and decision making all centered on a few managers. In addition, any

one essential manager that gets sick or is away from work for any period could

be traumatic to the organization.

2. Do you think other organizations should attempt to replicate Nucor’s structure?

Why or why not?

Answer: Although lean and simple, it may not be easy or effective to replicate it.

Simple structures work best in smaller organizations because of its flexibility

and simplicity.

3. Why do you think other organizations have developed structures much more

complex than Nucor’s?

Answer: Many organizations structure in a more bureaucratic way since it is a

traditional structure. Being highly routine, many employees function better in

structured and defined departments with specific rules and policies. Much can

be learned from Nucor, though, as they have been a leader in their industry.

4. Generally, organizational structures tend to reflect the views of the CEO. As

more and more “new blood” comes into Nucor, do you think the structure will

begin to look like that of other organizations?

Copyright ©2011 Pearson Education Inc. publishing as Prentice Hall

Chapter 15 Foundations of Organization Structure Page 489

Answer: Probably, the structure will need to adjust to the growth of the

company. New management often brings their styles and ideas with them from

other companies and they may change the structure if they are not comfortable

in a simple structure.

Source: P. Glader, “It’s Not Easy Being Lean,” Wall Street Journal (June 19, 2006), pp. B1, B3.

Copyright ©2011 Pearson Education Inc. publishing as Prentice Hall

Chapter 15 Foundations of Organization Structure Page 490

Case Incident 2

Siemens’ Simple Structure–Not

There is perhaps no tougher task for an executive than to restructure a European

organization. Ask former Siemens CEO Klaus Kleinfeld.

Siemens, with 77 billion Euros in revenue in 2008, some 427,000 employees, and

branches in 190 countries, is one of the largest electronics companies in the

world. Although the company has long been respected for its engineering prowess, it’s

also derided for its sluggishness and mechanistic structure. So when Kleinfeld took over

as CEO, he sought to restructure the company along the lines of what Jack Welch did

at General Electric. He has tried to make the structure less bureaucratic so decisions

are made more quickly. He spun off underperforming businesses. And he simplified the

company’s structure.

Kleinfeld’s efforts drew angry protests from employee groups, with constant picket lines

outside his corporate offices. One of the challenges of transforming European

organizations is the customary active participation of employees in executive decisions.

Half the seats on the Seimens board of directors are allocated to labor representatives.

Not surprisingly, the labor groups did not react positively to Kleinfeld’s GE-like

restructuring efforts. In his efforts to speed those efforts, labor groups alleged,

Kleinfeld secretly bankrolled a business-friendly workers’ group to try to undermine

Germany’s main industrial union.

Due to this and other allegations, Kleinfeld was forced out in June 2007 and replaced

by Peter Löscher. Löscher has found the same tensions between inertia and the need for

restructuring. Only a month after becoming CEO, Löscher was faced with a decision

whether to spin off the firm’s underperforming 10 billion-Euro auto parts unit, VDO. He

had to weigh the forces for stability, which want to protect worker interests, against

U.S.-style pressures for financial performance. One of VDO’s possible buyers is a U.S.

company, TRW, the controlling interest of which is held by Blackstone, a U.S. private

equity firm. German labor representatives have derided such private equity firms as

“locusts.” When Löscher decided to sell VDO to German tire giant Continental

Corporation, Continental promptly began to downsize and restructure the unit’s

operations.

Löscher has continued to restructure Siemens. In mid- 2008, he announced elimination

of nearly 17,000 jobs worldwide. He also announced plans to consolidate more business

units and reorganize the company’s operations geographically. “The speed at which

business is changing worldwide has increased considerably, and we’re

orienting Siemens accordingly,” Löscher said.

Since the switch from Kleinfeld to Löscher, Siemens has experienced its ups and downs.

Since 2008, its stock price has fallen 26 percent on the European stock exchange

and is down 31 percent on the New York Stock Exchange. That is better than some

competitors, such as France’s Alcatel-Lucent (down 83 percent) and General Electric

(down 69 percent), and worse than others, such as IBM (up 8 percent) and the

Swiss/Swedish conglomerate ABB (down 15 percent).

Though Löscher’s restructuring efforts have generated far less controversy than

Kleinfeld’s, that doesn’t mean they went over well with all constituents. Of the 2008

Copyright ©2011 Pearson Education Inc. publishing as Prentice Hall

Chapter 15 Foundations of Organization Structure Page 491

job cuts, Werner Neugebauer, regional director for a union representing many Siemens

employees, said, “The planned job cuts are incomprehensible nor acceptable for these

reasons, and in this extent, completely exaggerated.”

When asked by a reporter whether the cuts would be controversial, Löscher retorted, “I

couldn’t care less how it’s portrayed.” He paused a moment, then added, ““Maybe that’s

the wrong term. I do care.”

Questions

1. What do Kleinfeld’s efforts at Siemens tell you about the difficulties of

restructuring organizations?

Answer: Global restructuring is difficult. The guide to global structures at

http://74.125.47.132/search?q=cache:_E0UAS88Wd0J:macy.ba.ttu.edu/Fall%

252006/5371/overview%2520of%2520eight%2520types%2520of%2520structur

e%2520for%2520110106.ppt+global+organizational+structures&cd=16&hl=en&

ct=clnk&gl=us&client=safari suggests criteria that includes organizational and

local cultures into labor relations. These vary widely and must be addressed

uniquely to restructure.

2. Why do you think Löscher’s restructuring decisions have generated less

controversy than did Kleinfeld’s?

Answer: Löscher’s efforts focused on attempts to keep local organizational

culture in place. Kleinfeld’s efforts seemed more formula in implementation and

less sensitive to individuals. Although the results were similar, Löscher’s effort

was probably seen as more appreciative of the worker’s plight.

3. Assume a colleague read this case and concluded “This case proves

restructuring efforts do not improve a company’s financial performance.”

How would you respond to this statement?

Answer: The colleague’s position does recognize long-term outcome of

performance. Any restructuring carries a period of productivity drop because of

the changes implemented. These changes include personnel, job definitions, job

processes, and departmental relationships. All of these can cause drops in

productivity in initial implementation that will improve after the “learning curve”

is completed and new processes and relationships become the norm.

4. Do you think a CEO who decides to restructure or downsize a company takes

the well-being of employees into account? Should he or she do so? Why or why

not?

Answer: The answer will depend on student beliefs and opinions. In general

most students will say that consideration of employees is more important.

However, students should see that the CEO’s responsibility is to shareholders. A

balance must be made between employee consideration and shareholder equity.

Over consideration in either direction can create an unmanageable situation for

the CEO.

Sources: Based on A. Davidson, “Peter Löscher Makes Siemens Less German,” The Sunday Times (June 29,

2008), business.timesonline .co.uk; G. Frey, “Siemens Cutting 17K Jobs Worldwide to Cut Costs,” Fox News

(July 8, 2008), www.foxnews.com; M. Esterl and D. Crawford, “Siemens CEO Put to Early Test,” Wall Street

Journal (July 23, 2007), p. A8; and J. Ewing, “Siemens’ Culture Clash,” BusinessWeek (January 29, 2007), pp.

42–46.

Copyright ©2011 Pearson Education Inc. publishing as Prentice Hall

Chapter 15 Foundations of Organization Structure Page 492

Instructor’s Choice

Applying the Concepts

If one were to chart the growth spurts of Volkswagen over the past three decades, the

chart would look like a roller coaster. Plans were for former BMW boss Bernd

Pischetsrieder to fix ailing VW when he came aboard in 2002. However, best-laid plans

often go astray. VW’s share price is down almost 50% and profits fell by 36%. What is

wrong at VW? First, VW has always been able to charge more for its cars because of

quality, innovation, styling, and an implied lifetime guarantee. In recent years, however,

consumers have decided that the company is going to have to come up with more value

for the dollar if loyalty is to be retained. Second, sales in China’s booming market (VW

was one of the first car makers on the scene in this giant economy) have plummeted

and GM has driven VW from its number one ranking. Third, cost-cutting moves have

not worked. Fourth, VW uncharacteristically has labor pains. The CEO has had little

luck in reversing these problems because his consensus management techniques are

having little impact on VW’s change-resistant bureaucracy. Over half of the company’s

100 managers are not used to making their own decisions. This spells even more

trouble for the company in the year ahead.

Using a search engine of your own choosing, investigate Volkswagen’s

performance over the past two years. Write a brief summary of their fortunes

and misfortunes.

Visit the Volkswagen Web site at www.vw.com. From information supplied,

characterize the company’s existing structure.

Based on what you have observed in “a” and “b” above, suggest a new

organizational structure for the company. Cite any assumptions that you made

when you developed your structure.

Instructor Discussion

Students will be able to find a wealth of information on VW (particularly negative

information because of their recent performance). A nice summary article appears in

BusinessWeek (see August 9, 2004 “Volkswagen Slips into Reverse” pp. 40). Students

are free to pick any organizational form that they believe is best given the existing

situation. However, they should be aware that the current CEO is not having much

success with modern structures as the company seems to be very tradition-bound at

present. Students might also interview a local VW dealer for opinions.

Copyright ©2011 Pearson Education Inc. publishing as Prentice Hall

Chapter 15 Foundations of Organization Structure Page 493

EXPLORING OB TOPICS ON THE

WORLD WIDE WEB

Search Engines are our navigational tool to explore the WWW. Some commonly used

search engines are:

www.goto.com www.google.com www.excite.com

www.lycos.com www.hotbot.com www.bing.com

1. The chapter discusses span of control and the various advantages and

disadvantages of wide vs. narrow. Let us see how that looks in actual numbers.

First, determine how many hierarchical levels there are in at least three

organizations of varying sizes that you are currently involved with. One could be

the college or university you attend, another where you work, and finally a club

or religious institution you belong to. Or, for one of the choices, select a non-

profit organization you have some interest in. (For example, Red Cross, MDS,

American Cancer Society, etc.). Obtain their hierarchical structure either by

searching the WWW (most annual reports have information on this), calling or

visiting them, or drawing the structure yourself if you are involved in the

organization. Use www.google.com to help you search.

2. What factors influence virtual teams? For a short analysis point to:

http://www.seanet.com/~daveg/articles.htm. Write a short paragraph or two

outlining why you would or would not like working in a virtual environment. Do

you see a time later in your career when you would prefer working in a virtual

team? Why or why not?

Copyright ©2011 Pearson Education Inc. publishing as Prentice Hall

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Conceptual FrameworkDocument5 pagesConceptual FrameworkDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Management AccountingDocument5 pagesManagement AccountingDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fact Sheet Cbi Value TrustDocument2 pagesFact Sheet Cbi Value TrustDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Model Based Controller With Internal Model Control (IMC) Which Tunning by Set Point and Disturbance On Power Plant Based HYSYSDocument2 pagesModel Based Controller With Internal Model Control (IMC) Which Tunning by Set Point and Disturbance On Power Plant Based HYSYSDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Costco: A Strategic Analysis: Chloe Danica CrissoneDocument21 pagesCostco: A Strategic Analysis: Chloe Danica CrissoneDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Viewlocity Case Ford LTR Lres 0610Document8 pagesViewlocity Case Ford LTR Lres 0610Doni Sujana100% (1)

- Environmental Quality Management Volume 13 Issue 2 2003 (Doi 10.1002 - Tqem.10113) Robert B. Pojasek - Lean, Six Sigma, and The Systems Approach - Management Initiatives For Process ImprovementDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Quality Management Volume 13 Issue 2 2003 (Doi 10.1002 - Tqem.10113) Robert B. Pojasek - Lean, Six Sigma, and The Systems Approach - Management Initiatives For Process ImprovementDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Office Location Problem (Chapter 3)Document4 pagesThe Office Location Problem (Chapter 3)Doni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Wtwds Compensation Surveys Indonesia FlyerDocument2 pages2017 Wtwds Compensation Surveys Indonesia FlyerDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 04.layout Oral PresentationDocument2 pages04.layout Oral PresentationDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 14 SolutionsDocument10 pagesChapter 14 SolutionsAmanda Ng100% (1)

- Gitman Ch.5Document14 pagesGitman Ch.5Doni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3.03.1 Simple Six Sigma CalculatorDocument2 pages3.03.1 Simple Six Sigma Calculatormuda1986Pas encore d'évaluation

- Amadubi Rural Tourism Project in Jharkand ASLIDocument14 pagesAmadubi Rural Tourism Project in Jharkand ASLIDoni SujanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Untitled PresentationDocument6 pagesUntitled PresentationWayne ChenPas encore d'évaluation

- General Mathematics - Module #3Document7 pagesGeneral Mathematics - Module #3Archie Artemis NoblezaPas encore d'évaluation

- TARA FrameworkDocument2 pagesTARA Frameworkdominic100% (1)

- MAT 120 NSU SyllabusDocument5 pagesMAT 120 NSU SyllabusChowdhury_Irad_2937100% (1)

- News StoryDocument1 pageNews StoryRic Anthony LayasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Maria Da Piedade Ferreira - Embodied Emotions - Observations and Experiments in Architecture and Corporeality - Chapter 11Document21 pagesMaria Da Piedade Ferreira - Embodied Emotions - Observations and Experiments in Architecture and Corporeality - Chapter 11Maria Da Piedade FerreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review SampleDocument13 pagesLiterature Review SampleKrishna Prasad Adhikari (BFound) [CE Cohort2019 RTC]Pas encore d'évaluation

- AVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDocument16 pagesAVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDejan MitreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Conservation of MassDocument7 pagesLaw of Conservation of Massحمائل سجادPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Consumer Behavior: by Dr. Kevin Lance JonesDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Consumer Behavior: by Dr. Kevin Lance JonesCorey PagePas encore d'évaluation

- DragonflyDocument65 pagesDragonflyDavidPas encore d'évaluation

- Michelle Kommer Resignation LetterDocument1 pageMichelle Kommer Resignation LetterJeremy TurleyPas encore d'évaluation

- MacbethDocument2 pagesMacbethjtwyfordPas encore d'évaluation

- Cosmology NotesDocument22 pagesCosmology NotesSaint Benedict Center100% (1)

- TTG Basic Rules EngDocument1 pageTTG Basic Rules Engdewagoc871Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kalki ProjectDocument3 pagesKalki ProjectMandar SohoniPas encore d'évaluation

- Firewatch in The History of Walking SimsDocument5 pagesFirewatch in The History of Walking SimsZarahbeth Claire G. ArcederaPas encore d'évaluation

- DSP Setting Fundamentals PDFDocument14 pagesDSP Setting Fundamentals PDFsamuel mezaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Holy See: Benedict XviDocument4 pagesThe Holy See: Benedict XviAbel AtwiinePas encore d'évaluation

- DaybreaksDocument14 pagesDaybreaksKYLE FRANCIS EVAPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. Orbecido Iii Case DigestDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Orbecido Iii Case DigestCristine LabutinPas encore d'évaluation

- AZ-300 - Azure Solutions Architect TechnologiesDocument3 pagesAZ-300 - Azure Solutions Architect TechnologiesAmar Singh100% (1)

- Mécanisme de La Physionomie HumaineDocument2 pagesMécanisme de La Physionomie HumainebopufouriaPas encore d'évaluation

- New Memories by Ansdrela - EnglishDocument47 pagesNew Memories by Ansdrela - EnglishB bPas encore d'évaluation

- Wulandari - Solihin (2016)Document8 pagesWulandari - Solihin (2016)kelvinprd9Pas encore d'évaluation

- The University of Southern Mindanao VisionDocument9 pagesThe University of Southern Mindanao VisionNorhainie GuimbalananPas encore d'évaluation

- BangaloreDocument1 229 pagesBangaloreVikas RanjanPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs VictorDocument4 pagesPeople Vs VictorEryl YuPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Stereotypes and Performativity Analysis in Norwegian Wood Novel by Haruki Murakami Devani Adinda Putri Reg No: 2012060541Document35 pagesGender Stereotypes and Performativity Analysis in Norwegian Wood Novel by Haruki Murakami Devani Adinda Putri Reg No: 2012060541Jornel JevanskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Vitae: Lungnila Elizabeth School of Social Work, Senapati, Manipur August 2016-June 2018Document4 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Lungnila Elizabeth School of Social Work, Senapati, Manipur August 2016-June 2018Deuel khualPas encore d'évaluation