Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Cinema Beyond Film 2010 PDF

Transféré par

Giada Di TrincaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Cinema Beyond Film 2010 PDF

Transféré par

Giada Di TrincaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 1

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=1

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the

publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f 7b403487001

ebrary

Cinem a Beyond Film

ebrary

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f7b 403487001

ebrary

ebrary

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 2

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=2

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f 7b403487001

ebrary

eb r ar y

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f7b 403487001

ebrary

eb r ar y

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 3

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=3

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

C i n e m a Beyond F ilm

M e d ia E p i s t e m o l o g y in t h e M o d e r n E ra

Edited by François Albera and Maria Tortajada

Am st er d a m U n i v er si t y Pr ess

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 4

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=4

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

This publicat ion is m ade possible b y a gran t from t he Facult é des Let t res de

l'U n i ver si t é de Lausann e, Réseau Ciném a CH .

Translat ed b y Lance H ew son

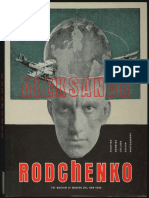

Front cover illust rat ion: The Zoopr axi scope b y Eadw ear d M uybr idge (1893)

Back cover illust rat ion: Runn er w i t h appar at us for recording speed (M arey).

D esign: Cl ai r e Angelini, M unich

Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Am st erdam

Lay-out : j a p e s, Am st erdam

I SBN 978 90 8964 083 3 ( p ap er b ack )

I SBN 978 90 8964 084 0 ( h ar d co v er )

e-I SBN 978 90 4850 807 5

NUR 674

© François Alber a and M ar i a Tort ajada / Am st er dam U n i ver si t y Press, Am st er

dam 2010

A l l right s reserved. W it hout lim it ing the right s un der copyri ght reserved above,

no part of this book m ay be reproduced, stored in or int roduced into a ret rieval

syst em , or t ransm it t ed, in an y form or b y an y m eans (electronic, m echanical,

phot ocopying, recording or ot herwise) w it hout the writ t en perm ission of both

the copyr i ght ow n er and the aut h or of t he book.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 5

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=5

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

C o n te n ts

A c k n o w le d g m e n ts 7

In tr o d u c tio n t o an E p is te m o lo g y o f V ie w in g and L is te n in g

D is p o s itiv e s 9

François Albera and Maria Tortajada

1 Epist em o l o g y

T h e 1900 E p is te m e 25

François Albera and Maria Tortajada

P ro je c te d C in e m a ( A H y p o th e s is on th e C in e m a ’s Im a g in a tio n ) 45

François Albera

T h e Case f o r an E p is te m o g ra p h y o f M o n ta g e 59

The Marey M om ent

François Albera

T h e ‘ C in e m a to g ra p h ic S n a p s h o t’ 79

Rereadi ng Et ienne-Jules M ar ey

Maria Tortajada

T h e C in e m a to g ra p h ve rsus P h o to g ra p h y , o r C y c lis ts and T im e in

th e W o r k o f A lfr e d J a rry 97

Maria Tortajada

2 Exh ib itio n

D y n a m ic P aths o f T h o u g h t 117

Exhibit ion Design, Ph ot ogr aph y an d Circulat ion in the W ork of

H erbert Bayer

Olivier Lagon

T h e L e c tu re 145

Le Cor busi er 's U se of t he W ord, D r aw i n g and Project ion

Olivier Lugon

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 6

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=6

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

6 Films that W o rk

3 Bo d y a n d V o i c e

D a n c in g D o lls and M e c h a n ic a l Eyes 17 1

Tracking an O bsessive M ot ive from Ballet to Cinem a

Laurent Guido

F ro m B ro a d c a s t P e rfo rm a n c e to V ir tu a l Show 19 3

Television's Tennis D isposit ive

Laurent Guido

T h e L e c tu re r, th e Im a g e , th e M ach in e and th e A u d io -S p e c ta to r 215

The Voice as a Com ponent Par t of A u d i ovi su al D isposi t ives

Alain Boillat

O n th e S in g u la r S ta tu s o f th e H u m a n V o ic e 233

Tomorrow's Eve and the Cult ur al Series of Talk i ng M achines

Alain Boillat

A b o u t th e A u th o r s 253

B ib lio g ra p h y 255

In d e x o f N a m e s 259

In d e x o f T itle s 265

In d e x o f S u b je cts 269

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 7

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=7

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

A c k n o w le d g m e n ts

The edit ors are gr at eful to Thom as Elsaesser for m ak i ng t his publishing project

possible, and t hey w an t to em phasize that the U n iver sit y of Lausan n e (UNIL),

the Facul t y of H um anit ies of U N I L and t he Reseau/ N et w er k Cinem a CH con

t ribut ed to the realizat ion of t his project. They t hank too the edit ors at AU P,

Jeroen Son der van and Jaap W agenaar, for sol vi n g problem s of an y sort.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 8

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=8

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f 7b403487001

ebrary

ebrary

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f7b 403487001

ebrary

ebrary

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 9

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=9

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

I n t r o d u c t i o n t o an E p i s t e m o l o g y o f V i e w i n g

and L is te n in g D is p o s itive s

François Albera and Maria Tortajada

For som e years now, scholars w or k i n g in the H i st or y and Aest het ics of the Cin

em a D epart m ent of the U n i versi t y of Lausan ne's Facult é des Let t res have been

act ivel y en gaged in research and t eaching t hat st em s from their belief that, at

the present m om ent in t ime, one can no longer restrict one's approach to cinem a

to t he n ar r ow field and specific object t hat w er e est ablished in the ear ly decades

of t he 20t h century, an d t hat culm inat ed in the sem iot ics approach of the 1970s.

Par adoxi call y enough, t his apot heosis occurred just as t he m odel t hat in circa

1906 had reflect ed t he independent and specific nat ure of cinem at ogr aphy and

the cinem at ographic inst it ut ion w as clearly becom ing obsolet e w it h the m ult i

plicat ion bot h of the m odes of capt uring film (first vi deo, t hen the D VD , com

put ers, m obile t elephones, etc.) and of au di ovi sual com m unicat ion support sys

t em s and m edia (in par t icular t elevision, an d m ore recent ly the Internet).

The 'r et u r n ' to hist ory on the one h an d1 and the hist oricizing of aest hetics on

the ot her hand - w i t h the lat t er t hereby bypassi n g an essentialist , ont ological

approach - are based on a n ew appr oach to the archive. Th ey al low the re

searcher t o w i den the field of invest igat ion and exam ine an ew the different

quest ions relat ed t o cinem at ographic 'l an gu age' and the problem at ics of repre

sent at ion —i.e., the pract ices and t heories of vi ew i n g and list ening w hich devel

oped dur i n g the 19t h cent ury and w er e linked to the rapid indust rial and tech

nological developm en t of w est ern societ ies. The cinem a is one of those

inst rum ent s that condenses a w h ol e series of dist inct ive charact erist ics of indus

t rial and t echnological societ y (serialisat ion, the division of w or k , m ult iplica

tion, m echanisat ion, st andardisat ion, speed, globalizat ion, etc.) - w here a whole

series of quest ions converges —from the social t o the political, t he m edical to the

ideological, the art istic t o the ant hropological, etc.

Since the m iddle of last cent ury, it can be said that the field has been broaden

ed by the ar r ival of the 'm ass m edi a' and m ass com m unicat ion in t heir relat ion

to n ew m edium s and m edia - the focus has m oved from t elevision to the Inter

net, digit al t echnologies, and furt her beyond, to the issue of cloning. The key

posit ion t hat cinem a occupied in the 1950s has consequent ly becom e relat i

vi zed, even t hough its 'm odel ' cont inues t o organise m uch of the im aginat ion

in the shape of t he pr ocedures i n volved in t he m eans of com m unicat ion and

m edia represent ation.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 10

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=10

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

10 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

O nce one is aw ar e t hat the par adi gm has shifted, one can, correlat ively, t ake a

fresh look at the 'ci n em a' sequence it self and approach it from ot her angles.

Research into 'ear l y cinem a' has paved the w ay for t his re-exam inat ion by high

light ing its pr im ar i l y het erogeneous aspect s t hat bot h the hist ory and the aes

t het ics of legit im at ion had suppressed. These t rait s had been par t ly en vi saged in

cert ain lines of research - i n cludi ng the n ow ad ays disregarded but im port ant

w or k of t he Institut de Filmologie (1947-1962) —w hich allow ed one in part icular

to m ake a heurist ic dist inct ion bet ween 'cinem at ic fact ' and 'film ic fact ', while

m aint aining a rest rict ive m odel of the 'cinem at ic'.2

In the w ak e of our cont act s w i t h 'ear l y cinem a' specialist s such as Laurent

M annoni, Tom Gunning, A n dr é Gaudr eaul t and Thom as Elsaesser, and as a

result of our interest in n ew t heories st r addl i n g the hist ory of art, phot ography

and t he m eans of com m unicat ion devel oped b y such scholars as Jonat han

Crary, Friedrich A . Kittler, Philippe H am on and St efan An dr i opoul os, w e

decided to focus on an epist em ological reflect ion on t hese quest ions in order to

produce a r evit alised concept ual fr am ew or k for our hist orical an d theoretical

research, cover ing bot h the hist ory of cinem a and the aest hetics of cinem a and

its language.

The fr am ew or k that has been devel oped arises out of a hypot hesis, the '1900

epist em e', w hi ch epit om ises t his b od y of phenom ena, discourses and pract ices,

m an y of w h ose dist inct ive feat ures w er e incorporat ed into 'cinem a' over a per i

od of several decades.

The foun dat ion of our reflect ion is a redefinit ion of the quest ion of t he 'd i spo

sit ives', w hi ch can be used to const ruct a schem a that t hen becom es an inst ru

ment of research.

D is p o s itiv e , e p is te m o lo g y

W e shall n ow clar i fy the t w o k ey t erm s t hat w e use: 'di sposi t i ve' and 'epist em ol-

°gy'-

The t erm 'di sposi t i ve' h as com e into English academ ic discourse t hrough the

t ranslat ion of w or k s b y such scholars as M ichel Foucault . The di sposi t i ve is a

net wor k of relat ions. The French equivalent , 'disposit if, w as ori gi nall y used in

legal cont ext s, and t hen spread to include the idea of disposit ion, whet her of

t roops or in the field of m echanics. The w or d is so great ly exploit ed in French

t oday t hat som e of its original force has been dilut ed. It m ay designat e an y t ype

of t echnical organisat ion or const ruct ion, or any arrangem ent , i ncluding wit h

hum an act ors, as lon g as it correlat es act ant ial posit ions and relat ions. In

French, it w as qui ck l y t aken int o t he realm of scientific or t echnical experim ent s

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 11

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=11

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Introduction to an Epistemology o f Viewing and Listening Dispositives

(where one also speak s of experim ent al 'prot ocols') and is w i d el y used in con

t em por ar y art to speak of an 'inst allat ion'.

The not ion of di sposi t i ve is of part icular interest here as it includes ever yt hi n g

t hat is laid out in front of the spectator, t oget her w it h all the elem ent s that al low

the represent at ion to be vi ew ed and heard. The disposit ive i n volves bot h the

m ak i n g and the show ing. The term is used w h en one or other of these aspect s

is addressed, on condit ion t hat it i s considered as a net work of relat ions be

t ween a spect ator, the represent at ion and t he 'm ach in er y' that allow s the spec

t ator to h ave access to the represent at ion (cf. 'The 1900 Epist em e'). H owever , the

t ask of r en ew i n g the hi st or i ogr aphy of the cinem a and, m ore generally, the

au di ovi sual dom ain vi a the not ion of di sposi t ive im plies const ruct ing a k n ow l

edge (savoir) t hat reduces the concept neit her to a strict hist orical act ualizat ion

nor to a causal genealogy.

It is im port ant to st ress t hat di sposi t i ves have bot h a concrete exist ence —a

cinem a audit orium act ually exists —and a di scursive existence. For exam ple, a

part icular phon ographic pract ice m ay on l y be found in discourse, e.g., in lit

er ar y discourse. M oreover, ou r long-t erm aim is not to describe the di sposit ives

t hem selves, but the net work of not ions, t heories, beliefs and pract ices that are

w oven into the discour ses direct ly relat ed to the elem ent s of the disposit ives,

w h i ch are t hem selves put in relat ion w it h in t hese discourses. By approaching

di sposi t i ves from the an gle of discourses, w e are aim ing to const ruct the condi

t ions of possibilit y of the disposit ives t hem selves as const ituted knowledge.

For M ichel Foucault , the not ion of di sposi t ive cam e to be increasingly asso

ciat ed w i t h a st rat egic perspect ive, and then a perspect ive of pow er; m oreover,

the t echnologies of cont rol (the key exam ple being the panopticon) do not t hem

sel ves define the cat egory of disposit ive, w h i ch is w ider, i.e., the di sci pli n ar y re

gim e or sexualit y. In ot her w or ds, from Foucault 's point of view, neit her 'cin

em a' n or the w h ol e collect ion of audio and vi sual 'm achines' in t hem selves

const itute 'di sposi t i ves' but w ou l d have to be seen as belon gin g to an all-en

com passing whole. W hen Paul Vi rilio int roduced the problem at ic of a 'logist ics

of percept ion', he heralded such a w hole, w hich w ou ld h ave sit uat ed disposi

t ives of vi ew i n g (and, for us, list ening) w it h in a hist orical w hole. But his idea

has been only ver y par t i al ly developed.

O ur definit ion of di sposi t i ve has t herefore not been si m pl y bor r ow ed from

Foucault : it com es not on l y from t he exchanges in the field of the hist or iogr aphy

of cinem a, and par t icular ly 'ear l y' cinema, but also from the broaden i n g of the

discipline, w h i ch has freed it self from sem iot ic or aest hetic discourse on the one

hand and a pur el y t echnical (i.e., hist orical or funct ionalist ) discourse on the

other. This is the back gr oun d of our specific epist em ological approach.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 12

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=12

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

12 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

W hen one defines the di sposi t i ve as a n et wor k of relat ions that goes beyond

the di sposi t i ve it self, one is al r eady in a sense i m plyin g a m et hod for defining

the object.

It is also im port ant to clar ify our use of t he t erm 'epist em ology'. Back in 1969,

Foucault preferred to speak of 'ar ch aeol ogy', as a reflection of his decision to

w or k on the m ar gins of the sciences, on w h at Gast on Bachelard him self rejected

as an 'epist em ological obst acle' (i.e., the discourses and i m agi n ar y beliefs that

obst ruct the t heoret ical and st r aight for w ar d const itution of the scientific con

cept), and Loui s Al t h usser reject ed as ideology. The present book covers sim ilar

t errit ory: the 'k n ow l ed ge of di sposi t i ves', t heir condit ions of possibilit y, is a di f

fuse k n ow l edge t hat is not det erm ined b y a t ype of enunciat ion or institution.

D isposit ives intersect wit h m any discourses - m any more t han t hose discourses

that are fi ght in g for the inst it ut ionalizat ion of di sposi t i ves t hem selves - such as

cinem a and phot ography. The discourses t hat appear in the follow i n g chapt ers

are literary, scient ific and t echnical, and m ay i n volve var ious ot her fields (legal

and econom ic), social pract ices (t ourism, sport ing event s) and, of course, cult ur

al pract ices and spect acles (theatre, the circus, etc.). In ot her w or ds, the k n ow l

edge of di sposi t i ves is not on l y const ruct ed w it hin the het erogeneit y of sources

and dat a, but also in the confront at ion bet w een the discursive and the concrete

hist orical object, the social pract ice that it im plies, and so on.

Ar ch aeology is used here to m ean an epi st em ology t hat does not aim at scien

t ific coherence - but it is not the epi st em ology of a tekne. It aim s to const ruct an

episteme - a k n ow l edge t hat is confront ed w i t h pract ices.

I ‘ T h e 1900 E p i s t e m e ’

The opening chapt er of the vol um e, 'The 1900 Epist em e', is a paper that Fran

çois A l ber a an d M ar i a Tort ajada gave at a D om it or Int ernat ional Associat ion

sym posium . It bu i l d s on the h ypot hesis that the new condit ions of vi ew i n g that

arose out of the indust rial societ y of the 18t h an d 19t h cent uries reform ulat ed

the 'spect at or-spect acle' schem a by int roducing the quest ion of the dispositive,

w h ich assign s a n ew place to the vi ew er w it hin a t ripart it e spectator-machine-

representation. This t ripart it e represent at ion m ust be const ruct ed as an epistemic

schema and, as such, int egrat ed w it hin a net work, a w i d er epist em ic configura

tion (that of cinem at ics, M ar ey's p h ysi ol ogy of m ovem ent , or social pract ices

such as the r ai l w ay journ ey and the spect acularisat ion of the l andscape, br i n g

in g t oget her an im m obile spect at or, a m obile spect acle and a fr am ew or k of v i

sion). Furt herm ore, in its capacit y of schem a, it pr ovides a m odel not only w i t h

in the rest rict ed field of vi ew i n g and list ening disposit ives, but going beyon d to

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 13

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=13

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Introduction to an Epistemology o f Viewing and Listening Dispositives 13

encom pass t hat of vi suali t y (paint ing, lit erat ure) and even t hat of t hought ('cin

em a', a m odel of k n ow l edge according to Bergson, a m odel of the psychic appa

rat us for som e psych ologi st s or psych oan alyst s). The epist em ic schem a thus

com bines the specificat ion of the concrete elements of the var ious disposit ives

w i t h t he concepts that are linked to them, for exam ple, the not ions of break ing

d ow n m ovem ent , t em poral im m ediacy or deferred broadcast ing, etc. Finally, in

order for the schem a to be const ruct ed, it is vit al sim ult aneously to devel op a

st u dy of discourses, a st udy of concrete disposit ives, and a st udy of the inst it u

t ional and social pract ices t hat are bot h en gaged b y and en gage t hese di sposi

t ives.

François Al ber a's chapt er ent itled 'Project ed Cinem a (A H ypot hesi s on the

Cinem a's Im aginat ion)' fol low s on from the perspect ive out lined in 'The 1900

Epist em e' by exam inin g a hist orical and t heoretical appr oach to the problem at ic

of t echnical invent ion t hat r evol ves around audio and vi sual disposit ives. H is

vi si on encom passes not on l y l it erary texts (Villiers de l'I sl e A d am , de Ch ousy

and Jules Verne), iconic t ext s (Robida), an d scientific popularisat ion (Cam ille

Flam m arion), but also w r i t er s and philosophers (Rabelais, Cam panella, Sorel

and Cyr an o de Bergerac) w h o w er e act ive long before the em ergence of cinema

and w h o t hus belon ged to a different t opic, and ot hers w r i t i n g in the w ak e of

the adven t of cinem a (Raym ond Roussel, Saint -Pol-Roux, René Bar javel and

Bi oy Casares, as w el l as Gi u seppe Lipparini, M aurice Renard, M aurice Leblanc,

Léon D audet and m an y others). H i s hypot hesis is that the 'ut opi as' of com m u

nicat ion t echnologies are not so m uch im aginat ions of precursors or prospect ive

fant asies as st ages of the invent ion it self t hat t ake the shape of act ualizat ions of

the pot ent ial inherent in the t echnologies of the day. Leavi n g aside the fact that

t hese fict ional w or k s w er e par t and parcel of the invent ion that w as about to

com e into being, t hey offer fert ile gr oun d for experim ent at ion, a space for ext ra

polat ion based on research and exist ing appar at uses or m achines, and thus t hey

bear w i t n ess bot h to t he im agi nar y side of t hese t echnologies and the expect a

t ions to w hich t hey gi ve rise. I n the w ak e of Gilbert Sim ondon's reflect ions on

the 'm od es of exist ence of t echnical object s', one m ay indeed suggest that the

'gen esi s' of the i nvent ion is const ituent of it. These 'fict ions' consequent ly reveal

cert ain dim ensions of exist ing t echnologies from w hich t hey borrow, but which

the cat alogue of hist or y - t hat gi ves precedence to one of the chosen usages -

fails to record. W hat w e h ave here is bot h the pot ent ial relat ed to the m edium or

m achine (once one has m oved from sm all-scale product ion or the prot ot ype to

generalisat ion) and the expect at ions t hat t hey create, whet her social, im aginary

or pragm at ic. The t w o t ypes of discourse (fictional and learned on the one side,

t echnical on the ot her) m ust t hus be pit t ed one against the ot her w it hin a space

t hat is com m on to both. This l eads to the reconfiguring of the au dio-visual field,

w h i ch gr ew out of social, indust rial or ideological 'specialisat ions' that sim pl y

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 14

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=14

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

14 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

ignored not on l y project s, but also t ransit ory expect at ions or realisat ions. In t his

regard, one can cit e t he exam ple of 'ph ot osculpt ure' or the 't heat rophone'. Fi

nally, these confront at ions reveal the spaces of int elligibilit y of the n ew t echnol

ogies and t he concept ual and sem ant ic field that is associat ed w i t h them, and

t hus define t he m ent al fram e of the invent ion and its recept ion (Apollinaire ex

t rapolat ed vi r t ual i m ager y from the gram ophone, w hi l e Saint -Pol Roux cam e

up w i t h hum an cloning from the cinema-m achine).

In 'The Case for an Epi st em ogr aph y of M ont age: The Marey M om ent ', A l ber a

set s out to redefine t he concept of 'm on t age'. This in volves re-exam ining the

Marey quest ion or Marey 'm om en t ' in t he hist ory, prehist ory or ar ch aeology of

cinem a. Albera dist in guishes bet w een on t he one hand the t echnical-aest het ic

discourse on m ont age (the epistemonomical level), w hich creat es a set of limit s

and cont rol principles and 'r ul es', and on the ot her hand t he pr escr ipt ive di s

course of cinem a crit icism and t heory (the epistemocritical level), w hich defines

the processes of inclusion in or exclusion from t he concept of m ont age. This led

him to const ruct the ' epistemological' l evel of m ont age. On t his level, it is vit al not

only to pinpoint the fields of applicat ion of the concept s and rules of usage, but

also to ident ify t ransform at ions and variat ions, in order to relat e them to their

condit ions of possibilit y. The aim is to underst and h ow the concept ual field of

m ont age has been t ransform ed (via such not ions as end, piece, m om ent , int er

val, intermittence, pause, phase, posit ion, jerk, shock, dissociat ion, cut, break,

interruption, discont inuit y, joining, assem bling, collage, link, continuity, art icu

lation, succession, etc.) by l eavi n g behind the pur el y internal, descript ive or pr e

script ive definit ions and by goi ng beyon d obst acles of the t echnological t ype

w h i ch i m pede or lim it com prehension. This m akes it possible bot h to ident ify

the cont ours of a m ont age funct ion, w h i ch m ay not be gi ven t hat nam e but

w hi ch needs to be linked to var i ous procedures, pract ices and ut t erances, and

to locat e the t hinking relat ed to m ont age in the syst em of concept s and pract ices

w h er e it has it s roots, and subsequent ly en vi sage its ext ension and variabilit y. In

t his perspect ive, t he M ar ey 'm om ent ' is a k ey elem ent of the puzzle: not only

w as he out side cinem at ographic t eleology and yet present in t he sequence of

'ci nem a' invent ions (both concept ually an d t echnically speaking) and gave the

'invent i on' bot h scient ific an d social respect abilit y (Académie des sciences, Collège

de France), but he belon ged to a field - ph ysi ol ogy - that had been w el l explored

in concept ual t erm s and w as t he scene of fundam ent al cont roversies bet ween

opposi n g t endencies, aboun di n g in a bod y of not ions, concept s and pract ices

that w as to pr ovide an 'i nt erface' w i t h the t oys and m achines used for anim at ed

im ages. M ar ey's mechanistic concept ion (the 'an i m al m achine') w ou ld lead to his

di scover y of a machinic di sposi t i ve that is an alogous to his object as an inst ru

ment of observat ion - the 'ci nem a' machine.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 15

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=15

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Introduction to an Epistemology o f Viewing and Listening Dispositives 15

M ar i a Tort ajada's t wo cont ribut ions, 'The "Cin em at ogr aphi c Sn apshot ": Re

reading Etienne-Jules M ar ey' and 'The Ci n em at ograph ver sus Phot ography, or

Cycl ist s and Tim e in t he W ork of A l fr ed Jar r y', set out to define the idea of cin

em a and t he idea of phot ography, t wo di sposit ives that w er e sim ilar at around

the t urn of the 20t h cent ury and yet in opposit ion to each other. W hen cinema

em erged, it w as phot ogr aph y that played a part in defining its concept s and the

i m ager y associat ed w i t h it. Phot ography foun ded the 'cinem a', or a cert ain idea

of t he cinem a at this m om ent in time. M eanw hile, phot ogr aph y it self t ook on a

n ew st at us in it s confront at ion w it h cinema. Exam i n in g the relat ions bet ween

the t wo di sposi t i ves m eans expl or i n g the m echanical sources of modernit y,

since the not ion of di sposi t i ve is int rinsically linked to m echanics and cine

m at ics - m ovem ent and speed are associat ed both wit h cinema and phot ogr a

ph y in a var i et y of w ays.

Et ienne-Jules M ar ey's research is a k ey fact or for un derst an din g 'cinem a' at

the chronophot ographic st age and pr ovi des a m eans of obser ving h ow cinema

br ok e aw ay from phot ography. It can be ar gued that one cannot conceive of

cinem a w it h out t ak i ng chr onoph ot ogr aphy into account . By m ast ering the tech

nique of the phot ographic snapshot , M ar ey conceived of a k ind of 'cinem a' t hat

w as det erm ined by the concept ual and m et hodological prem ises of his scientific

approach.

The phot ogram is generally considered a fixed i m age that is opposed to the

reconst it ut ed m ovi n g i m age that defines cinema. H owever, w hen one re-reads

M arey, one begin s to see that w h at fundam ent ally dist inguishes cinem a from

ph ot ogr aph y i s not si m pl y t he illusion of m ovem ent . The ver y st at us of phot o

graphy, of the fi xed im age, i s t ransform ed by the cinem at ographic disposit i ve -

the phot ogram is a snapshot w h ose nat ure i s a par adoxical one. The an alysis

put for w ar d here is based on a redefinit ion of the not ion of instant , associat ed

w i t h the t echnique of the phot ographic snapshot and det erm ined by t he expo

sure t ime. The aim of the chapt er is to sh ow t hat one can conceive of an instant

that lasts. This is w h at t ranspires w h en one begins to const ruct the concept s

link ed w i t h the instant of illum inat ion in M arey's wr it ings. One can see h ow

t hese concept s m ake u p a syst em of relat ions w it hin his var i ous scientific pr o

posal s relat ed t o the phot ographic snapshot and chr onophot ogr aphy on fixed

plat es and film . This is the idea that Ber gson dism issed w hen he radically sepa

rat ed t he inst ant from the fl ow of time.

A l fr ed Jar r y is associat ed w i t h one of the m ajor t hem es of m odernit y: m e

chanizat ion. H i s novel, The Supermale (1901), is an excellent exam ple of a series

of reflect ions on 'bach elor m achines'. There are on ly a lim it ed num ber of explicit

references to t he cinem at ograph, but one can nevert heless sh ow just h ow im

port ant it w as to Jarry. H i s w or k is of int erest because his writ ings, whet her

fict ion or journalism , expl or e the pot ent ial of cinem a that el udes not on ly m ost

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 16

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=16

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

16 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

aspect s of the cinem at ographic di sposi t i ve of his cont em poraries, but also w h at

w as to develop lat er and becom e dom inant today. Jar r y's w or k s gi ve concret e

form to som e of cinem a's unexplor ed pot ent ial, as t hey use cinem a to conceive

and represent a cert ain experience of t ime and speed linked to m odernit y. They

use cinem a to project t hem selves into a philosophical fiction, Jar r y's 'pat aph y-

sics'. Jar r y's i deas are a clear illust rat ion of the fact that disposit i ves should be

underst ood w i t h i n a syst em of relat ions. Cinem a and phot ography are brough t

t oget her by m eans of the presupposit ions that their represent at ions set in m o

tion. In short , t hey st and in opposit ion to several of t heir defining charact eris

tics, w hich link them t o a net work of not ions or pract ices belonging to the

hi gh l y par adoxi cal m odernit y t hat Jar r y describes.

The references to ph ot ogr aph y and cinem a m ay t hus be put in parallel. Be

t ween a concept ion of the inst ant and a concept ion of m ovem ent and speed,

bet w een Zen o an d Bergson, Jar r y p l ays w i t h the par adoxes of t ime by m ak ing

them m at erialise as represent at ions t hat can only be ful l y underst ood by refer

ence to the di sposi t i ves of vi ew i n g and list ening.

2 T h e e x h ib itio n

The second sect ion of the book exam ines the disposit ive of the 'exhibit ion' and

it s relat ion to the cinem at ographic disposit ive. O livier Lugon 's t wo chapt ers

t ake the reader beyon d cinem a pr oper b y st u dyi n g the w ay in w hich cinem a

w as t aken beyon d its ow n lim it s w h en it crossed pat hs w i t h ot her m edia. H e

develops t w o exam ples: t he exhibit ion and t he lecture, calling on t wo of the key

figur es of m odernism , H erbert Bayer for t he exhibit ion and Le Cor busier for the

lecture. Bot h explicit ly referred t o cinem a as a m odel, and especi ally to the idea

of a cert ain di sposi t i ve w h ose var i ou s elem ent s t hey ut ilised in order to explain

different aspect s of their ow n designs. These i nclude a t em poral and rhyt hm ic

definit ion of vi sual art, the sequent ial nat ure of the film , the event -like charact er

of the present at ion of lum inous im ages, t he pl ay of silence and of the voice, and

the effect s of surprise or shock t hat are at t ribut ed to m ont age. These are all

forces t hat can be used to capt ure the spect at ors' attent ion and can t hus be

hi gh l y efficient for the com m unicat ion of ideas.

These t wo exam ples sh ow us h ow com m unicat ion in the 20t h cent ury relied

not on l y on the form s of represent ation, but also on the control over the d i sposi

t ive of 'sh ow i n g' and the m eet ing bet ween the spect at or and the im age. The

specific nat ure of the spat ial and t em poral fr am ew or k used to present the im

age, i.e., w h at sur r ounds and suppor t s it, m ay be as im port ant for const ruct ing

its m eanin g as w h at it act ually cont ains.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 17

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=17

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Introduction to an Epistemology o f Viewing and Listening Dispositives 17

This is the case w i t h phot ography, w hi ch is an alysed t hrough the w ay it is

exploit ed in the st agin g of H erbert Bayer 's exhibit ions. In 'D yn am i c Pat hs of

Thought : Exhibit ion D esign, Phot ogr aphy and Circulat ion in the W ork of H er

bert Bayer ', Lugon describes Bayer 's career as an artist, graphic desi gner and

exhibit ion designer from Ger m an y in t he 1920s to the U S of the 1940s. H e looks

at the t heoretical foundat ion of Bayer 's w or k and the w ay it evol ved over the

year s, w it h part icular at t ent ion pai d to t he om nipresent quest ion of the spect a

t or's m obilit y and circulat ion. H ere i s the ver y cent re of Bayer 's strategies,

w her e he t urns the m ovem ent s of vi si t or s into a tool of com m unicat ion. H e cre

at es scenarios by bu i l d i n g circuit s, d evel opi n g narrat ive and em ot ional se

quences by set t ing out a rout e and channelling spect at ors t hrough it. This can

be seen in the M oM A 's 1942 pr opagan da exhibit ion, The Road to Victory, where

the principle of cinem a is r ever sed by locat ing the developm ent of the m ont age,

narrat ion and em ot ional dr am a in t he spect at ors' ver y m ovem ent s. Thus, ph ysi

cal m obilit y est ablishes a par t icular form of 'ci nem a' w h i ch by claim ing to lead

to great er part icipat ion in fact t ends to increase the psychological hold it exer

cises over the spect at ors.

'The Lect ure: Le Cor busi er 's U se of t he W ord, D r aw i n g and Project ion' looks

at the lecture as a di sposi t i ve and m ult im edia 'spect acle' t hrough Le Corbusier's

ext en sive experience as a lecturer. H e devot ed fort y year s to his 'lect ure t echni

que' b y d evel opi n g m ult iple and changing form s of interact ion of voice, direct

dr aw i n g, and the project ion of fixed and m ovi n g im ages. H e t hus em bellished

his scenic and perform at ive art b y exploit ing m echanical form s of show i n g

im ages, the aim bein g to devel op a force of persuasion t hat w ou l d go beyond

the act ual event it self b y m eans of furt her publicat ions and exhibit ions, which

w er e t hem selves charact erised b y t hese scenic disposit i ves and com plex form s

of project ion accom panied by spoken comment ary.

3 V o ic e /b o d y

The t hird sect ion of t he book looks at quest ions that relat e to h ow m anifest a

t ions of hum an presence m at erialise wit hin t he represent at ions that em erge

from di sposi t i ves i n vol vi n g m achines. A l ai n Boillat an d Laurent Guido exam ine

the m echanical evolut ion of t he hum an elem ent w it hin ant hropocent ric audi o

vi su al di sposi t i ves an d concent rat e on t w o elem ent s - the voice and the bod y -

t hat belon g t o different aspect s of spect acular pract ices. On the one hand, con

siderat ions of t he voice's st at us h ave been com m on w it hin the m ajor par adi gm s

t hat det erm ined the developm en t of t echnological and cult ural series and that

share m uch w it h the 'ci n em a' series - in par t icular the m eans of reproducing

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 18

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=18

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

18 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

and br oadcast i n g soun ds du r i n g t he second h alf of the 19t h century. These con

siderat ions have det erm ined h ow t he int eract ions bet w een the audit ive and v i

sual dim ensions of the represent at ion w er e en visaged (i.e., the im age of the t alk

in g subject). On the ot her hand, t he issue of the body refers not on ly to cert ain

m odes of an alysi n g and represent ing hum an m ovem ent t hat w er e developed

over t his sam e period, but also to cert ain scenic approaches that w er e adopt ed

w it h in part icular di sposi t i ves and t hat t hese di sposi t ives t hem selves influenced.

There is, of course, a fundam ent al difference bet ween the disem bodied voice of

the phon ogr aph or t elephone and the physical presence of the body show n by

vi ew i n g di sposit ives. N onet heless, bot h voi ce and body are m anifest in the 'pre-

sence-absence' schem a that is inherent to ever y represent ation, t hough in var y

in g degrees and in accordance wit h a vari et y of m odalit ies.

M anifest at ions of the voice and the im age of the bod y are som et im es t rans

posed in t ime and/ or space and m ay also be fi r m ly locat ed in the hie et nunc of

product ion-recept ion. A l ai n Boillat d r aw s a dist inct ion bet ween talking cinem a

and spoken cinem a in order to account for t his dist inct ion bet ween the fixing of

the voi ce by the m achine and the l i ve sit uat ion of orality. These t wo syst em s

cannot be d i vi d ed into strict periods, even i f the lect urer of ear ly cinem a did

becom e a m ajor figur e of the talkie, but can be exam ined from the perspect ive

of 'cinem a' archaeology. Q uot at ion m ar k s should be used here, as the objective

is to dism ant le the 'ci n em a' object in order to exam ine the t echnological series or

par allel t radit ions of the spect acular, such as t he t alking or dancing autom at on,

the phonograph, opera, etc. In 'Th e Lect urer, the Im age, the M achine and the

Audio-Spect at or: The Voice as a Com ponent Part of A u d i ovi su al D isposit ives',

Boillat reflect s on t he use of 'soun ds before the t alkie' b y fol low in g t wo lines of

enquiry. Firstly, he focuses on the oft en over looked voice, w h ose specific char

act erist ics have to be st udied in order to underst and the phenom ena that it in

volves. Secondly, he uses Al ber a's and Tort ajada's concept of the vi sual di sposi

t ive to exam ine t he roles of the l i ve speaker, w h o is a verit able m ediat or

bet ween the audience and the screen. This second prem ise m eans adapt i n g A l

bera's and Tort ajada's param et ers to include interact ions bet w een im ages and

sounds —i.e., m ak i n g the net wor k of relat ions result ing from the sim ult aneous

presence of t he three poles of the di sposi t i ve m ore com plex and broaden i n g the

'm ach i n er y' t o i nclude a w i d er w hole, w i t h hum an act ors and the product ion

space of the au di ovi su al represent at ion. Boillat also looks at w h at oralit y im

plies w hen it is an int egral par t of a product ion space that is par t ly machinic in

charact er. The t heoret ical fr am ew or k is based on the cont em porary account s or

the hypot heses of ear ly cinem a hist orians, and al low s one to en vi sage how the

lect urer's different funct ions var i ed according to the place t hat w as at t ribut ed to

him. The cinem at ographic spect acle i s not en visaged from one vi ew poi n t but

calls on the diver si t y of t he di sposi t i ves used.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 19

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=19

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Introduction to an Epistemology o f Viewing and Listening Dispositives 19

The w or l d of fiction —w her e the possible can t ake concrete shape - w as the

preferred m eans of expr ession for the im aginat ion and the im agi nar y w or l ds

t hat em erged from t he spr eadi n g of (audio)visual t echnologies. Thus, to an sw er

the quest ions r egar di n g cert ain specific disposit ives, one needs to t ake into ac

count the l it erary t ext s t hat feat ure m achines t hat perform before an audience in

a fict ional cont ext . W rit ing t hus becom es a m ediat ion that m irrors t he au d i ovi

sual product ion produced b y a disposit ive, w h i le offering an indicat ion of how

the di sposi t i ve m ight be received. In 'O n t he Sin gular St at us of the H um an

Voice: Tomorrow's Eve and the Cult ur al Series of Talk ing M achines', A l ai n Boil-

lat highlight s t he issue of the inscript ion of the voice by exam ining Villiers de

l 'l sl e A d am 's novel, Tomorrow's Eve, w i t h it s w el l-k n ow n exam ple of 'project ed

cinem a'. H e uses the perspect ive of the ar chaeology of t alking 'cinem a' to exam

ine the place and funct ion of the voice vi a ant hropom orphic sim ulacra - a gen

uine audi ovi sual di sposi t i ve —in de Villiers's n ovel and, m ore generally, the spe

cific charact erist ics of the voi ce considered as an affirm at ion of the presence of

the hum an in the m achine. W hen the voice is reproduced vi a the phonograph, it

l eads to a syst em of 'presence-absence' that can be com pared to Christ ian M et z's

w r i t i n gs on the 'i m pr essi on of r ealit y' in the cinema. In Tomorrow's Eve, Edison's

i nvent ions - which, in epist em ological terms, are observed in all t heir diversi t y

(and not just t he oft -quot ed descript ion of st ereoscopic projection) —are asso

ciat ed w i t h t he principle of delinking that is generally hidden in t alk ing cinem a

because of the pr i m ar y posit ion accorded to the unique speak i n g subject. The

an guish brough t about b y the dehum an izing exhibit ion of the machinic dim en

sion seem s bot h to un der pin the novelist 's fetishist ic descript ion of the t echnol

ogy and encourage interest in the occult , w i t h Villiers calling on a spiritist ar gu

m ent t hat w as sym pt om at ic of t he w ay recorded voi ces w er e underst ood at the

end of the 19t h century.

Lauren t Guido's chapt er ent it led 'D an ci n g D olls and M echanical Eyes: Track

i n g an O bsessive M ot ive from Ballet to Cin em a' uses a sim ilar approach. Gui do

hi ghlight s cert ain var iat ions in a disposit ive where the spectacle of the dancing

bod y is m ediat ised vi a a vi ew i n g t echnique t hat set s out t o en large and exam ine

the det ails of a physical perform ance. H e i nvest igat es the represent at ions t hat

refer first and forem ost to lit erary w r i t i n gs that w er e m ark ed by the Rom ant ic

reaction to the m echanist ic m odel (H offm ann, Kleist ), and t hen concent rat es on

the i m agi n ar y w or l d of libret tos and cert ain processes t hat are part icular to

French ballet . H e also exam ines the t heoret ical quest ions that dom inat ed the

art s that w er e inspired b y bod y m ovem ent s w hen the cinem at ograph w as being

developed. There em erges the concept ion of a hum an —u su al l y fem ale - figure

t hat is pr ogr essi vel y r educed to it s m echanical dim ension, and lim it ed in part i

cular to the rhyt hm ic param et ers that em erged from the scientific st udy of

m ovem ent , w h er e the body w as t reat ed as a m ere object. The chronophot o-

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 20

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=20

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

20 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

graphic and t hen cinem at ographic cam era w er e developed as analyt ical inst ru

ments, before finall y est ablishing t hem selves as the prost het ic tool par excellence,

cover in g funct ions that w er e pr evi ou sl y occupied by such t echnologies as the

opera glass.

H ow ever , one should not confine oneself to t he i m agi n ar y represent at ions of

disposi t i ves but , w h en considering the body, bear in m ind a m ore pragm at ic

considerat ion of t he var i ous w ays in w h i ch the cinem at ographic represent at ion

reform ulat es cert ain fundam ent al charact erist ics of vi ew i n g in the scenic arts.

One of the k ey m odels that influenced the aest hetic and social reflect ions on

the audi ovi sual spect acle w as the opera, especially W agn er 's ut opian Gesamt

kunstwerk and its i deal of a rhyt hm ic int eract ion bet w een the different m odes of

expression. H owever, it is the less recognised form s of t heat re and dance (i.e.,

the m usic hall, acrobat ics and the circus) w hich, from a hist orical perspect ive,

w er e t he k ey fact ors t hat influenced the w ay the bod y w as handled in the cin

em a. This can be seen in the short act s reconfigured for the cam era in ear ly film s

or the count less m usicals and choreographic perform ances show n in cinem as or

on t elevision. Irrespect ive of whet her these perform ances const itute the film 's

m ain t hem e or are si m pl y par t ly aut onom ous m om ent s of attraction, t hey refer

to t w o canonical m odes of represent at ion of the body. On the one hand, there is

the respect for the int egrit y of the original physical perform ance. On the ot her

hand, the perform ance is edit ed and insert ed in a dyn am ic series of shots. Both

of t hese im port ant par adi gm s m ake u p var i ed and secondary act ualisat ions of

primary di sposi t i ves relat ing to the code of body m ovem ent s in scenic spect a-

Laur ent Guido, in his chapt er ent itled 'Fr om Broadcast Perform ance t o V i r

t ual Show : Television's Tennis D i sposi t i ve', concent rat es on one of the relat ion

ships bet ween t w o successive di sposit ives. H e ai m s syst em at i cal l y to i dent ify

som e of t he aest hetic and dram at ic im plicat ions of h ow t ennis is film ed and

edit ed w h en it is broadcast live, in ot her w or d s the m edia disposi t ive t hat t urns

it into a t elevision spectacle. Part icular at tent ion is pai d both to the relat ionship

bet w een the scenic represent at ion that is em ployed in the st adium and to the

sequencing of the different vi ew poi n t s that m ake up the film version, by in

creasing t he num ber of cam eras used. The recurring fi gures t hat st and out du r

in g t his l i ve cutting are organ ised b y sw it ch ing bet ween the all-encom passing

and geom et rical vi si on of the m at ch (over vi ew from above or even from the air)

and a series of shot s t hat concent rat es on t he i n di vi dual gest ur es and emot ions,

w h i ch are m ai n l y film ed at court level. W hile exam ining different br oadcast s of

the W im bledon t ennis t ournam ent over the period 1997-2007, Guido also

adopt s a hist orical perspect ive t hat highlight s h ow som e t radit ional uses and

m odes of represent at ion h ave been m aint ained over a long period, w h ile ot hers

h ave changed. This change is especially evi den t in the not ion of 'plur ifocali t y'

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 21

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=21

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Introduction to an Epistemology o f Viewing and Listening Dispositives 21

and the quest ion of the an alysi s and anim at ion of 'i n vi si bl e' gest ures t hat arose

w it h the first phot ographic and cinem at ographic im ages of sport s event s, from

Geor ges D em eny to Leni Riefenst ahl.

O v e rtu re

The cont ribut ions in the current vol um e are part of a broader research project

bein g conduct ed at the U n i ver si t y of Lausanne. A series of relat ed devel op

m ent s h ave been un dert aken eit her by t he aut hors of the present book (biblio

graphical det ails of w hom can be found below ) or b y researchers, lect urers and

PhD st udent s w h o are current ly w or k i n g on sim ilar t hemes. Som e exam ples of

current research project s include m edical discourses linked to the appearance of

the cinem a at the end of the 19t h cent ury, the archaeological appr oach to

voyeur i sm , w h i ch evol ved into one of the recurrent concept s of cinem at o

gr aphi c st udies, the int roduct ion of au di ovi sual t echnologies in cont em porary

t heat re an d h ow t hey have affect ed not on l y the act or's body but also the t elevi

sion di sposi t i ve as it spr ead in t he 1950s, and finally Sw i ss nat ional exhibit ions,

w her e bot h cinem at ic and au di ovi su al m eans have been r egularly em ployed.

This bod y of research st art s w i t h cinem a w h ile at t em pt ing to broaden the

field an d perceive it at a cr ossr oads of ot her cult ural, cognit ive or social series.

This is unique w it hin French-speak ing Europe, w h er e scholars are often con

cerned w i t h st ayi n g w i t h i n the boun dar ies of convent ional cinem a st udies as

defined b y cinem a crit ics and the general public. It is clear, however, t hat var

ious t ransform at ions, whet her on the t echnological l evel or t hose i n vol vi n g cus

t om s and social pract ices, h ave shift ed the boundar ies of t his restricted 'm odel'

once and for all. It w ou ld, h ow ever , be foolish to den y that the m odel it self is

goi n g t hrough a crisis. The field of art has absorbed cinem a w it hin a m edley of

disparat e cat egories; the n ew m edia h ave em ployed cinem a for ot her purposes

and connect ed it w i t h ot her sources. Even the param et ers of cinem a's canonical

exploit at ion are changing w it h the new, m iniat urized m eans of reproduct ion.

W hen w e exam ine the 19t h-cent ury novelist s w h o 'project ed' the fut ure cinema

and the aspirat ions and under t ak in gs of avant -garde art ist s and t heorist s such

as Lissit zky, Gan, Vert ov, Klut sis, Arvat ov, etc., w e see that 'ci n em a' pot ent ially

cont ained t oday's diversificat ion, or hint ed at possibilit ies t hat w er e n ever ful ly

developed. A r ch aeology is t hus a m eans of const ruct ing the present.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 22

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=22

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

22 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

N o te s

1. The perspective is quite different from that of the pioneers who fought for recogni

tion of the medium.

2. The emergence of film studies, launched by Gilbert Cohen-Seat in 1946, coincided

with the domination of cinema over the audiovisual field and beyond, the 'mass

media'. Its 'end' coincided with television taking over the dominant position, and

the fact that sociologists took other mass media into account (the illustrated press,

photographs, advertising etc.). Roland Barthes, who took part in research work at

the Institut de Filmologie, wrote about this 'move', which he himself made, in his

review of the 'First International Conference on Visual Information, Milan' (9-12

July 1961) (Communications no. 1, 1961) - he calls on people to question 'the imperi

alism of the cinema over the other means of visual information'. 'Cinema’s domina

tion is doubtless justified "historically"', he continues, 'but it cannot be justified

epistemologically'. One year previously, he stated that cinema was 'recognised as

the model of the mass media' ('Les "unites traumatiques" au cinema. Principes de

recherche', Revue intemationale de Filmologie, no. 34, July-September i960).

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 23

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=23

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f 7b403487001

ebrary

I

Epist em ology

ebrary

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f7b 403487001

ebrary

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 24

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=24

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f 7b403487001

ebrary

ebrary

7a956f5ffal0e58167e5f7b 403487001

ebrary

ebrary

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 25

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=25

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

T h e 1900 E p i s t e m e 1

François Albera and Maria Tortajada

In tro d u c tio n

The t echnical societ y that cam e into being in the 17t h cent ury and becam e the

flourishing indust rial societ y of the 19t h cent ury int roduced a series of n ew con

dit ions into t he field of i m age and sound. These condit ions influenced fir st l y the

effects t hat w er e sought and produced. There w as a m ove both to record and

reproduce r eali t y as exact ly as possible and, on the cont rary, t o create the fant as

tic and em body fant asy. There w as the por t r ayal of such phenom ena as m ove

ment, succession and t he fl ow of time. Secondly, and m ore significant ly, the new

condit ions had an im pact on t he means used, in ot her w or ds, the devi ces and

m achines.

The mechanical m odel, w hich began w i t h Descart es and de la M ettrie, over

t urned Arist ot le's physics and opened up a n ew concept ual space that gave rise

to a series of proposit ions concerning the m odes of apprehension of bot h objects

and beings, w i t h in part icular t he di vi si on into discret e unit s, w hich could then

be com bined. This concept ual space al low ed for the body's m obilising pow er

and dyn am i cs to be locat ed out side of it. The im port ance of the par adigm of the

clock in the sevent eent h cent ury is w el l k n ow n —the clock w i t h its w eigh t s and

the spr ing-dr iven wat ch w er e m icro-m echanism s that inaugur at ed a n ew state

t hat com bined t wo t ypes of m ovem ent s and stop m echanism s to achieve r egu

larit y; its effect is to t ransform m ovem ent into inform at ion. One m ight speak of

a 'clock -m ak ing' episteme spreadi n g im plicit or st at ed k n ow l edge in var i ous

w ays, in var i ous sect ors of k n ow l edge, ideas, pract ices and instit ut ions, k n ow l

edge based on dissociat ion, assem bling, art iculat ion, aut om at ism , etc. (the clock

or w at chm ak er w as a cent ral charact er in the 18t h cent ury t oget her w i t h clocks

and also aut om at a, right u p to M éliès's Robert-Houdin t heat re).2

W e speak here of episteme. The term, coined b y M ichel Foucault , i s proble

mat ic, par t ly because of the w ay it 'com pet es' in t his chapt er w it h the not ions

of 'm odel ' and 'par ad i gm ' w i t h w hi ch it is often confused. Foucault 's episteme

h as a charact erist ic w hi ch dist inguishes it from the paradigm (described by Tho

m as S. Kuhn)3 and a fortiori from the model, in t hat it does not define a state of

k n ow l edge - w het her scient ific or philosophical —at a part icular moment , but

t hat w hich m ak es a t heory, pract ice or opinion possible.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 26

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=26

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

26 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

Thus, one can say t hat the represent at ion of the 'm echanical er a' w as 'fit t ed

out w i t h t ools', 'engineer ed', and no longer used its own t echniques (those of the

paint er or sculpt or, t heir savoir-faire) but, inst ead, used inst rum ent s and t echni

ques desi gned for ot her ends. This 'equi pm en t ' of the processes of represent a

tion represent s one of the t ransform at ions of t his period, w h i ch w as charac

t erised by the prom ot ion of (existing) appar at uses from the st at us of instrument

to t hat of machine (D iirer em ployed apparat uses, as did the perspecteurs, but t hey

w er e cont rolled by their ow n hands).4 It is t rue t hat Bazin saw t his m ove to

automatism as the dispossession of m an as creator, but he im m ediat ely brough t

back Pr oviden ce into the liberat ed space: the phot ographic im print is the Veil of

Veronica, but there is no longer an i n t erm ediary (it is the art ist's 't em peram ent '

that is int erposed as a prism in Zol a's fam ous expression that is referred to

here). Bazin, cont rary to W alt er Benjam in, beli eved that one should do without

the appar at us because Veronica's Vei l is not the screen, it r eceives it s im print

usin g neit her lens nor exposur e t ime, n or developm ent , print ing, calibration,

etc. (and yet w hen N iepce t ook his first phot ograph, he w as i m m ediat ely sub

ject ed to t he w eigh t of the t echnical di sposi t i ve of his m achine w i t h it s t wo

sh adow s - al r eady the ver y 'fi r st ' landscape is not an im print in Bazin 's use of

the w or d: it records several t im e-periods because of the ver y nat ure of the m a

chine).

W hen Canalet t o int roduced his Cam er a O bscura in Venice's piazze and, as it

w ere, 'fi xed ' the l andscapes, he w as t aking part in t his aut om at ism ; w hen he

com bined different im ages, added a campanile t aken from elsewhere, m oved a

church or a palace, it w as because he w as able to conceive of the process of

dissociat ing and r eassem blin g a vi ew on the basi s of presupposit ions that w ere

not based on t hose of El Greco, w h o 't u r n ed' a bu ildin g around in his paint ing

of the Toledo lan dscape.5 An d a fortiori the phot ographer Gu st ave Le Gray, w h o

'm oun t ed' his i m ages from several n egat ives.

The int roduct ion of t his equipm ent led to a n ew t ype of relat ion bet w een ob

ject, apparat us, represent at ion and spect at or, w hi ch w as t o t ake concrete form

at a certain m om ent in the dispositives o f viewing and listening (i.e., an or gan i sa

tion that assi gn s posit ions to it s prot agonist s) —the cinem at ograph, phot ograph,

t elevision, phonograph, t elephone, etc., each of w hi ch assum ed var i ous st ruc

t ures and shapes. By exam i n i n g the condit ions of possibilit y of t hese d i sposi

t ives, w e shall const ruct w h at w e call t he 1900 episteme. Thanks to t his an alysi s

of the epist em ology of disposit ives, w e shall be in a posit ion to ent irely rest ruc

t ure the field of m odes of represent at ion, in cluding t radit ional m edia such as

paint ing or literat ure.

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 27

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=27

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

The 1900 Episteme 27

D i s p o s i t i v e s a n d m a c h in e s : h y p o t h e s e s

Ot her scholars h ave en vi saged t hese di sposi t i ves and m achines. From our point

of view , however, none of t heir appr oaches is sat isfactory. W e are r eferring here

first ly t o t he vi sion of the 1970s, w h en scholars such as Jean -Loui s Baudr y and

Jean-Pierre O udart concent rat ed on the cinem at ograph, w hich w as on l y exam

ined from the point of vi ew of t he per cei vi n g subject w i t h a Lacanian perspec

tive. Secondly, t here is Friedrich Kit t ler's t ransferring of the Lacanian t riad (ima

ginary, sym bolic, real) ont o that of the gram ophone, cinem a an d t ypewrit er, and

t hirdly Jonat han Cr ar y's an alysi s6 which, despit e its Foucauldi an prem ise, not

on ly fails to address the relat ion bet ween concrete ‘machinid di sposi t i ves and the

discourses he analyses, but also changes direct ion by fixing on the st ereoscope

as the place of rupt ure and em ergence of a phenom enological m odel of the sub

ject. Cr ar y sees t he int roduct ion of subject ivit y wit h t ime and durat ion, and fo

cuses on the subject rat her t han an alysi n g the const ruct ion of the subject vi a the

di sposi t i ve (for M ichel Foucault , there is no (phenom enological) subject, but

discur sive di sposi t i ves w hich assi gn a place to the subject and const itute it as

such —'t he disposit ive is above all a m achine w hi ch produces subject ivat ions').7

O ur hypot h esis is t herefore that the n ew condit ions of vi ew i n g and list ening

t hat em erged out of indust rial societ y h ave r edr aw n the spectator-spect acle

schem a b y int roducing the quest ion of the dispositive, w h i ch assi gns a n ew posi

tion to t hose w h o view . This can be seen not on ly in the int roduct ion of m a

chines and t ools t hat increase vi si on (from the t elescope to the m agic lantern),

and recording or capt uring devices (phot ography, the gram ophone), but also in

the prom ot ion-spect acle of the m anufact ured object, it s exhibit ion (as Philippe

H am on has show n w hen w r i t i n g about un i versal exhibit ions),8 t raffic condi

t ions (speed) and urban relat ions (shocks), as w ell as in the com m ent aries t hat

highlight such phenom ena.

There is no short age of exam ples of t his 'r egulat i on' b y t hese appar at uses and

m achines, w h i ch belon g to a w h ol e series of fields to w hich t hey w er e pr e

vi ou sl y not connect ed —the regulat ion or dom inat ion proceeding from the Pr äg

nanz of t heir m odes of funct ioning. Félix Fénéon w rot e about the sh adow t hea

tre in 1887 as follow s:

M. Henry Rivière has civilised the previously rudimentary art of the shadow theatre.

Before him, the shadows filed past like characters on friezes or 'Paronies'. When he

had to engineer M. Caran d'Ache's Epopée, he positioned them with an effect of per

spective at ever-greater distances, and thought up masterly and instantaneous tricks

to have the groups of characters advance and then disappear. Granted, the screen still

only showed black silhouettes, but at least it was no longer a naïve surface, and

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 28

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=28

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

28 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

achieved depth. And now there is decisive progress with the addition of every colour

- in forty minutes, forty tableaus hold their own.9

Em ile Verhaeren com m ent ed si m i lar ly on Cl au de M onet 's w or k s - the pict orial

realit y - vi a M ar ey's chronophot ographic m achine. A s it w as the represent at ion

of a landscape, he evok ed its 'successi ve aspect s, arrest ed in flight by an eye of

ext r aor di n ar y acu i t y'.10 M onet 's eye becom es the phot ographic gun, it capt ures

objects in m id-air, in cluding objects t hat are not necessarily birds. A s W histler

w r ot e to Fant in-Lat our in 1862: 'Yo u cat ch it [the instant] in flight just as you kill

a bir d in the ai r '.

These are som e exam ples of machinic elem ent s t hat m ake up t he disposit ive

before the advent of the cinema, and that the epist em ic schem a al low s us to for

m ulat e, avoi d i n g the cont ent -based, t eleological approach w hich w ou ld h ave

Fénéon 'ant icipat e' the successive im ages of the cinem at ograph in Rivier e's

sh adow theat re, or Verhaeren and W hist ler be 'un der t he influence' of or in

spir ed b y chronophot ography. The quest ion is of anot her order, and indeed re

fers t o t hat 'im plicit k n ow l ed ge' t hat m ak es such statement s possible.

The quest ion t hus becom es: w h at di d one call 'recreat ed m ovem ent ' in the

ninet eent h cent ury before the appearance of t he kinet oscope and the cinem at o

graph, and afterwards? This m ay seem to be a som ew hat unrefined variable, but

the an sw er is by no m eans a st r ai ght for w ar d one.

The not ion of m ovem ent , or even t hat of br eak in g out of the fr am ew or k of the

represent at ion, w as som et hing t hat could be effect ively realised before the ac

t ual product ion of m ovem ent b y the m achine or the effect of m ovem ent by

m eans of opt ical illusion. The enrapt ured critic, st anding in front of one of Gu s

t ave Le Gr ay's phot ographs, 't he Great W ave' (1858), w rot e t hat the spect at or

st an di ng in front of the i m age w as subjugat ed b y its exact ness and its rendering,

'an d w ou l d be t em pt ed to st ep back w ar d in order not t o be t ouched b y its fu r

ious m om ent um '.11 W hen di scussi n g such a reaction, one can, of course, t ake

into account the l it erary gar r ul ousn ess of the critic. This is, aft er all, w h at he

wr ot e aft er the event , and he w as not act ually caught in the act of backing aw ay

in the m anner of the first spect at ors at the Grand Café react ing in front of the

irrupt ion of t he locom ot ive. But t he fact rem ains t hat the critic cannot describe

such a reaction w it hout a cert ain agreem ent , w it h out it being acceptable to r ead

ers (irrespect ive of whet her t hey h ave seen the phot ograph). It should, m ore

over, be not ed t hat like Le Gray, the Lum ière brot hers set out to 'fi x' the m ove

m ent of w aves which, like that of sm oke, w i n d rust ling leaves, wat er falls, etc.,

produces a great er effect t han that of people par adi n g past , like in the sh adow

theat re. The not ion of effect is a crucial one for cert ain phot ographers and, t o a

large extent , addr esses the relat ion bet ween the represent at ion and the spect a

tor. Le Gr ay ent ers into som e det ail on t he quest ion in his treat ise of 1850.12

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 29

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=29

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

The 1900 Episteme 29

M ovem ent can be inferred from effect if the effect fi xes som et hing m ovin g w it h

part icular force (as is the case for a w ave).

This not ion of effect also al low s us to underst and h ow black-and-whit e phot o

gr ap h y in 1850 could belon g to the problem at ic of the colourist paint ers, w h o

br ok e w i t h the supr em acy of d r aw i n g in favou r of w or k on the 'econ om y of

light ', cont ours, nuances of t he sam e colour, or m ass processing w hich alone

suit ed colour, as Baudelaire w r ot e in his Salon of 1846 (TIL O n Colou r ').13

Such agreem ent in t he t ype of react ions aroused by a represent at ion can

doubt less be expl ai n ed b y the change brought about by phot ography when

com pared to a pict orial represent at ion, l eadi n g to a phenom enon of 'absorbment'

(the m eaning bein g a little different from M ichael Fried's 'absor pt ion'), several

exam ples of which w ere gi ven by D iderot in his descript ions (he const ruct ed a

n ar r at ive w h i ch i n vol ved penet rat ing inside the pict ure and n avigat in g w it hin it

—and even losing oneself inside it ).14 The phot ographic par adi gm t hus becom es

the int erprét ant of the different vi sual phenom ena.

In Le Gr ay's w or k , t his effect of br eaki n g out produced the dissociat ion of the

t w o planes (the sea and the sky), even i f the dissociat ion is not lit erally enact ed

but 'fak ed '. Since t he t w o elem ent s are not cont inuous, t hey produce the deh is

cence w hich sees the bot t om t hreat ening t o det ach it self from the top because

the respect ive precision of t heir execut ion m akes them dissociable, in a m anner

of speaking. The ack now ledged influence of the panor am a m odel on Le Gr ay

can be seen here, w her e t w o or t hree horizont al zones w er e superposed - the

sky, the sea and t he shore, w here not hing lim it ed t hem on the sides. H ere w e are

in a 'm achine' (wit h fak i n g by m eans of t w o juxt aposed negat ives) and a di spo

sit ive (the spect at or is i nvit ed to di scover an effect of precision that exceeds the

codes that are in force and is t hus brough t to a 'n ew vi si on ' of a phenom enon

t hat w as nevert heless w el l k n ow n and represent ed).

Thus, w e see t hat ph ot ogr aphy adopt ed som et hing of the di sposit ive of the

panoram a, before pain t ing bor r ow ed it from phot ogr aphy in the w or k s of

W histler, Courbet , M anet and Boudin. A s W alt er Benjam in w r ot e/ 5 Le Gr ay's

w ave spr ead in paint ing, w her e Courbet in part icular w on the reput at ion of

h avi n g fixed an inst ant aneous sn apshot .16

R esearch a im s

W e h ave decided neit her to espouse the approaches of the 1970s, nor to follow

in t he foot st eps of such scholars as Cr ar y — w h ose exam ple, despit e our re

serves, is an int erest ing one - but to exam ine the cinem at ographic disposit ive.

For the pur poses of ou r dem onst rat ion, it h as been reduced here to the 'vi ew -

. Cinema Beyond Film : Media Epistemology in the Modern Era.

: Amsterdam University Press, . p 30

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10459505?ppg=30

Copyright © Amsterdam University Press. . All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher,

except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

30 François Albera and Maria Tortajada

in g' di sposi t i ve alone, i m plyi n g t hat the 'li st en i ng' disposit i ve still has to be con

struct ed. O ur aim is t hus to describe and apprehend t his disposit ive:

1. as an episternic schema (definit ion);