Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

N ': New Conversations On Gender, Race, Religion and The Making of Communities

Transféré par

kanga_rooDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

N ': New Conversations On Gender, Race, Religion and The Making of Communities

Transféré par

kanga_rooDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

‘NOT ANOTHER HIJAB ROW’:

New conversations on gender, race,

religion and the making of

communities

Transforming Cultures eJournal,

Vol. 2 No 1, November 2007

http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/TfC

Guest editors’ introduction by Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

Headscarves in schools. Sexual violence in Indigenous communities. Muslim women at

public swimming pools. Polygamy. Sharia law. Outspoken Imams on sexual assault.

Integration and respect for women. It seems that around the world in the media and

public debate, women’s issues are at the top of the agenda. Yet all too often, support for

women’s rights is proclaimed loudest by conservative politicians intent on policing

communities and demonising Muslims during the ‘war on terror’. This edition of the

Transforming Cultures eJournal offers critical reflections on the contemporary politics

of gender, race and religion, and provides a platform for those perspectives which are

too often sidelined in the debate, perspectives that seek to go beyond simplistic debates

such as ‘hijab: to ban or not to ban?’ or ‘Muslim women: oppressed or liberated?’

While ‘hijab debates’ occur in various guises in France, the Netherlands, Germany, the

UK and elsewhere, questions of gender, race and religion have a particular pertinence in

Australia, where a combination of recent events has generated unprecedented public and

scholarly attention on sexual violence, ‘masculinist protection’, and ideas of the nation.

A moral panic around ‘ethnic gang rapes’ in 2001, the Cronulla riot of 2005, Sheik

Hilaly’s comments on ‘uncovered meat’ in 2006 and the federal government’s

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

intervention in the Northern Territory in 2007, all provide a unique opportunity to

critically examine how notions of gender, race and religion are at the core of current

debates about diversity, cohesion and change in contemporary societies. In contrast to

politicians and commentators who often simply assert that ‘tolerance’ and women’s

equality have been achieved in Australia, the papers here demonstrate ongoing struggles

and innovation at the intersection of antiracism and feminism.

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho ii INTRODUCTION

The collection arises out of a conference we organized in December 2006 at the

University of Technology, Sydney, entitled Not Another Hijab Row: new conversations

on gender, race, religion and the making of communities. We decided to hold the

conference because, despite a decade of ‘race debates’ in Australia, analyses of the

intersections between gender, race and religion remain all but absent in the public

sphere. In recent years Muslim women in particular have been subjected to intense

public scrutiny, yet these controversies have largely been limited to provocative

comments on the hijab and sharia law. These narrow debates have served to silence the

experiences and the concerns of Muslim women and of scholars and community

workers who engage the intersections of gender, race and religion.

The conference sought to establish a space for constructive dialogue around the

perspectives which are marginalised in public discussions, focusing on how gender, race

and religion shape notions of belonging and exclusion in Australia. Ideas around gender,

race and religion have long been deployed in the construction of national identity, and

are particularly evident in current representations of ‘aggressive’ and ‘misogynistic’

Islam as the ultimate alien other in ‘tolerant’ Judeo-Christian Australia. In minority

communities, questions over community leadership, representation, and responses to

racism have often revolved around constructions of culture, faith and gender roles. We

sought papers and presentations from all disciplinary perspectives in order to build a

conversation across spectra of belief, scholarship and community.

This interest developed through the ongoing work of the two conference organisers, Dr

Tanja Dreher and Dr Christina Ho, both of the University of Technology, Sydney. In

research on Muslim women and the media and on Muslim women’s networks, the

organisers found a need for ‘safe spaces’ to discuss issues of gender, race and religion,

as women’s rights had been ‘hijacked’ in public debate (Ho 2007) and Muslim women

struggled to be heard on their own terms in the media (Dreher 2003, 2006).

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

Why ‘Not Another Hijab Row’?

The title provoked many comments and questions in the lead up to the conference. The

most obvious question was – why not another hijab row? What’s the problem? Weren’t

we censoring legitimate debate? In fact the program included a number of very

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho iii INTRODUCTION

interesting papers addressing perceptions and experiences around Muslim women’s

covering. Our aim was not to ‘censor’ any mention of the hijab – as if we even could! –

but rather to suspend, for a short time, the intense focus on this one particular item of

clothing, significant though it is. One of the great ironies is that the more public debate

fixates on the hijab, the less space there is for Muslim women to talk about the range of

issues that affect their lives (see Hussein in this volume). Rather than censoring, the title

was intended to signal a shift in emphasis and a space for conversations that are not

limited by the simplistic terms of so much public debate.

Another common question – was this to be a conference about Muslim women? And

why were we, two non-Muslim women, organising it? While the conference was

intended to make a space for a diversity of Australian Muslim women’s perspectives

and experiences, it was not intended as a conference specifically for or about Muslim

women. For one thing, we were very aware that Muslim women in Australia regularly

organise all manner of events and conferences. As organisers we understood our role as

summed up in the subtitle – new conversations on gender, race, religion and the making

of communities. While Muslim women are currently under intense scrutiny, it is only

fitting that questions around Islam and gender should occupy a prominent position in

such a conference. But our overall agenda was a wider one, and we were very excited to

see the range of papers exploring issues around gender, nationalism, the secular-

religious divide, the politics of community and antiracism and interfaith work.

These are difficult times for those working at the intersection of gender and race. Too

often the media framing of events such as a Muslim cleric’s comments on sexual assault

or violence against women in Indigenous communities forces an intractable dilemma: to

defend communities experiencing racism is to be read as condoning violence against

women. With this conference we aimed to open up a space where the complexities of

these issues could be discussed. We were pleased at the number of papers that took up

the challenge to develop intersectional analyses – bringing together analyses of gender,

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

race, religion and community. So we aimed to provoke new conversations rather than

tired old debates, and to create a space for those voices that are so often marginalised in

Australian public debate – be they the voices of Muslim women, of critical feminism or

of those working with intersectional analyses and those who refuse essentialising

constructions of tradition and community.

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho iv INTRODUCTION

Challenges for contemporary antiracism

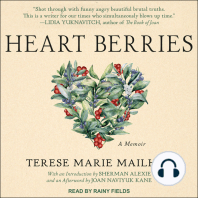

The cover image reflects something of the impetus for the timing of the Not Another

Hijab Row conference, on the first anniversary of the Cronulla riot. The image shows a

silent protest conducted at an anti-racism rally held in the weeks directly after the riot in

December 2005. The image of flag-draped heads was inspired by the work of Sydney

artists in the boatpeople.org project. Suvendrini Perera has analysed the image in her

reflections on the ‘racial terror’ enacted at Cronulla (2006: par 65).

‘Here the multiple functions of the flag, as hood, blindfold, weapon, threat

and disguise were put on display. Through its staging of the ways in which

the flag is mobilized as a racial and ethnonational emblem of exclusion,

the performance powerfully elucidates the ‘strange’ responses of

opposition and ‘ethnic dislike’ that the flag provokes. ‘Regular’, that is,

seemingly neutral and unmarked, identities such as ‘the ordinary

Australian’ and the ‘patriotic citizen’ are called in question as the racial

assumptions implicit in them are uncovered. It is only in such courageous

expressions of dissent in a climate of racist resurgence that the face of

white terror is – fleetingly but unforgettably – exposed.’

For one of us (Dreher), as a participant in the protest action, the experience was another

instruction in the politics of representation and the dilemmas of contemporary anti-

racism work. We spent considerable time in tying the flags to ensure that they would not

be read as hijab. Given previous experiences of misrepresentation, participants were

wary of media attention and a decision was taken to make no comment to journalists or

to onlookers. We toyed with titles for the image – ‘See no evil, Hear no evil, Speak no

evil’? ‘Blind nationalism or blind faith’? ‘Does my head look big in this?’ In the end we

decided against a title – no simple words or sound bite could capture the complex and

differing motivations of those who took part in the action.

The silent protest did attract considerable media attention, featuring in most mainstream

media coverage of the rally and some international outlets. Much to our horror,

Sydney’s tabloid, The Daily Telegraph added the caption, ‘veiled protest’, a reminder of

the mainstream media’s obsession with the image of the ‘veiled woman’ and an

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

inability to recognise the protest directed at the white supremacy and masculinist

violence on display at Cronulla. Weeks later the image was captioned as a photo of

rioters at Cronulla in the letters pages of the Illawarra Mercury. While the Editor

apologized privately, these misappropriations of the image suggest something of the

challenges of developing creative antiracism work in contemporary Australia. Protest

actions, public debates and community-level projects operate in the context of a

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho v INTRODUCTION

sustained retreat from both the language and policies of antiracism (see Ho and Dreher

2006). While the mainstream media has been a crucial forum for a decade of ‘race

debates’ in Australia, it is extremely difficult to mobilise irony or a complex politics of

representation within the news media (see Dreher 2003).

Despite the recurring attention to hijab in media and public debate, nuanced discussion

is remarkably rare. It is not surprising that the hijab or veil has become such a contested

symbol in the current climate of fear and hostility towards Muslims. As Bouma and

Brace-Govan (2000: 168) write, ‘This external bodily expression of an internally held

religious faith runs counter to Australian social expectations that religiosity is a private

affair and should be kept out of the public arena.’

In particular, the veiled woman has been the key symbol of the anxiety over Islam’s

‘oppression of women’. After September 11, images of veiled women reached ‘epic

proportions’ (Ayotte and Husain, 2005: 117), as the American crusade against Al Qaeda

became gradually a mission to ‘liberate’ Afghan women. During the invasion of

Afghanistan, the veil became a powerful ‘visual and linguistic signifier of Afghan

women’s oppression’ (Ayotte and Husain, 2005: 117), supposedly encapsulating all that

was wrong about the Taliban. Of course, this was simply the latest manifestation of a

long tradition dating to colonial times, when Western concerns about the status of

women within Islam frequently served as a moral justification for European colonialism

in the Middle East.

Yet, as Muslim and other scholars have comprehensively shown, the hijab cannot be

reduced to a simplistic symbol of oppression. Rather, veiling practices among Muslim

women have always reflected complex arrays of religious, personal, political and

national affiliations. From Egypt and Algeria to France, Germany and beyond, women’s

decisions to veil have historically symbolised allegiances, anxieties, oppositions and

identities in broader contexts of colonialism, modernisation, globalisation and change

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

(Abu Odeh 1993; Ahmed 1992; McLeod 1992; Timmerman 2000).1

1

MacLeod traces the ‘new veiling’ in the Islamic world to the 1970s, a movement ‘initiated as a political

and religious statement in the universities after the 1967 and 1973 wars with Israel’ (1992: 541), and

which, over the years, has been taken on different meanings ‘from country to country, class to class, even

individual to individual’ (1992: 540).

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho vi INTRODUCTION

At a more micro level, research on particular Muslim women’s veiling practices has

shown how the adoption of a pious identity can be used as a creative means for carving

out greater personal freedom within family and community contexts. For example,

studies have shown how young South Asian women in the UK appeal to Islamic

scriptures about the importance of education and women’s rights in marriage to justify

their desires to seek higher education or professional careers. As Butler (1999: 147)

argues, ‘These women are using Islam as a tool to question traditional culture’ (see also

Dwyer 2000; Samad 2004).

In Australia, Muslim women have been keen to defend the decision to wear the hijab as

a free choice, women’s own strong and independent expression of religious faith and

community affiliation. For example, one of the most prominent public campaigns of the

Sydney-based United Muslim Women Association in recent years has been its ‘pro-

hijab campaign’, which defends the right to wear a headscarf as a basic human right

under freedom of religion (UMWA 2005). As Shakira Hussein notes in her paper, such

efforts have been successful in gradually shifting public opinion on the hijab. A decade

ago, the idea of veiling as a woman’s free choice would not have been accepted in

‘mainstream’ Australia, whereas now, it is a relatively commonplace (though by no

means universally accepted) argument.

However, Hussein’s paper in this edition of Transforming Cultures argues that simply

presenting the hijab as a ‘choice’ is insufficient, because it traps discussions within a

simplistic dichotomy of ‘force’ versus ‘choice’. In the face of prevailing assumptions in

Western societies that Muslim women are ‘forced’ to veil, Hussein notes that it is

understandable that Muslim women have responded by asserting that veiling is their

‘choice’. However, she argues that neither position genuinely captures the more

complex reality of women’s dress code decisions, which are usually more about

‘negotiated compromised positions’.

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

Moreover, an unanticipated consequence of the defence of the hijab has been to

reinforce its position as a symbol of ‘authentic’ Muslim womanhood, thereby

marginalising the role of non-hijabis. Hussein draws on her own experience as a Muslim

commentator, who has been asked by journalists to don a hijab for the sake of the

camera. Presumably she is less than a fully authentic Muslim without one. In the face of

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho vii INTRODUCTION

these pressures, Hussein wonders how she can support her fellow Muslims’ right to veil

without simultaneously presenting the hijab as the marker of ‘true’ Muslim identity.

This is an important contribution to our understanding of the complexities of one of the

most essentialised and overburdened cultural symbols of our time.

The ‘new politics of gender’

Hijab debates are a crucial component of a contemporary politics of gender operating

during the ‘war on terror’ in the United States (Ferguson and Marso 2007) and in

Australia (Ho 2007). The key feature of this new politics of gender is the hijacking of

women’s rights and the use of feminised rhetorics to justify the ‘war on terror’ coupled

with policies which constrain women’s role under the rubric of ‘family values’. The

new politics supports particular interpretations of ‘women’s rights’, but is far from

feminist in that it is grounded in a conservative gender ideology which ‘characterizes

men as dominant, masculine protectors and women as submissive, vulnerable, and

therefore deserving of and in need of men’s respect’ (Ferguson and Marso 2007: 5).

While focusing on the now waning Presidency of George W Bush, Ferguson and Marso

argue that Bush’s ‘constellation of an eviscerated liberal feminism, a hierarchical gender

ideology, and a neoconservative security strategy’ represents a new politics of gender

which will have continued significance and impact for many years to come.

Iris Marion Young offers perhaps the most compelling analysis of the ‘logic of

masculinist protection’ at work in the current security state and the ‘war on terror’.

Rather than understanding masculinity as selfish, aggressive and domineering, ‘central

to the logic of masculinist protection is the subordinate relationship of those in the

protected position. In return for male protection, the woman concedes critical distance

from decision-making autonomy’ (Young 2007: 119). For Young, the current US

security state is a ‘protection racket’ founded on a tradeoff between protection and

subordinated citizenship. In the ‘war on terror’, the logic of masculinist protection is

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

used to justify US military interventions, most notably in the argument that Afghan

women would be ‘saved’ through the invasion of Afghanistan.

While the US analyses have focused on the position of Muslim women ‘over there’ in

need of saving and protection, and Afghan women in particular, the new politics of

gender in Australia has focused intense scrutiny on Muslim women within (Ho 2007).

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho viii INTRODUCTION

Australian Muslim women have found themselves at the centre of numerous public

debates and controversies – from hijabs in schools to access to public swimming pools

and recurring debates around Islam and violence against women. Muslim women have

become highly visible but have also found it extremely difficult to shift news agendas

and to be heard on their own terms (Dreher and Simmons 2005).

The apparent concern for the rights of Muslim women in Australian public discourse is

interestingly mirrored by an anxiety about the victimisation of white Australian women,

whether via sexual harassment, assault, or most sensationally of all, ‘ethnic gang rape’.

At the centre of this debate is the figure of the threatening ‘young Muslim man’, a topic

that Kiran Grewal, in this issue, tackles in her analysis of the public discussion of the

Sydney gang rapes and the 2005 Cronulla riots. Grewal argues that the portrayal of the

gang rapes racialised these crimes, presenting them as Muslim attacks on the Australian

community, rather than assaults on individual women.

This discourse has enabled the articulation of a paternalistic nationalism defined in

opposition to a ‘misogynistic’ and ‘oppressive’ Islam, that both oppresses its own

women, and now threatens ‘our’ (read: white) women. In this context, sexual assaults

committed by young Muslim men are attacks on Australia and its values, in stark

contrast to the less hostile portrayal of similar allegations against Australian sporting

heroes. Likewise, during the Cronulla riots, white Australian participants were simply

‘boozed up boys behaving badly’, while Lebanese and Muslim participants were

‘waging war’ against Australia.

Kiran Grewal’s piece in this collection is a timely contribution to a growing body of

Australian literature analysing the racialisation of crime and criminalisation of race (see

especially Collins et al 2000 and Poynting et al 2004). It also offers an important

gendered analysis of these debates, which is often under-acknowledged. Clearly, ideas

about masculinity and femininity intertwine in crucial ways with those about race and

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

culture to produce a discourse of white masculine protection of vulnerable women at

risk from the ‘enemy’ masculinity of the non-white other.

Anxiety over threats to ‘white women’ were exemplified in a ‘Bikini March’ planned to

mark the Cronulla anniversary in Melbourne on the same weekend as the Not Another

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho ix INTRODUCTION

Hijab Row conference. If the ‘flagheads’ protest in 2005 demonstrates something of the

limits of antiracism in public debate, ‘The Great Australian Bikini March’ planned for

2006 was a stark reminder of the centrality of gender in contemporary struggles around

‘Australian values’, immigration and border protection. The march was called as a

protest against earlier comments, widely debated in the media, by Sydney Sheik Hilaly

describing immodestly dressed women as ‘uncovered meat’ inviting sexual assault. The

organizer described herself as a ‘bikini-wearing grandma’ and urged women to march in

bikinis to the Islamic Information and Support Centre in Melbourne, calling for the

deportation of Sheik Hilaly and Melbourne’s Sheik Omran as well as ‘urgent citizenship

legislation’. White supremacist groups quickly joined the campaign, arguing that

women’s safety was under threat from ‘extremist Muslim attitudes’ towards women and

sexual assault. They said, ‘we must now stand together on this issue, regardless of what

other issues we might have, to ensure Australia’s wives, mothers, daughters and sisters

feel safe in their own country’. After discussions with Victoria Police and with a

number of community organizations, the march was cancelled. At the Not Another

Hijab Row conference, Joumanah el-Matrah of the Islamic Women’s Welfare Council

reported on the negotiations with the march organizer and the community BBQ and

mosque open day against racism and sexual assault held at the Islamic Information and

Support Centre on the day of the planned march.

The theme of racialised protection of women is productively juxtaposed alongside an

analysis of the political uses of secularism in Holly Randell-Moon’s paper in this issue,

‘Secularism, feminism and race in representations of Australianness’. Randell-Moon

powerfully dissects the political discourse of the Howard Government, to show how its

combination of ‘Australian values’ with secularism and gender equality allow it to

demonise Islam and Muslims as backward and misogynist.

Drawing on Ferguson’s analysis (2005) of the Bush Administration’s ‘feminised

security rhetoric’, which justifies the ‘war on terror on the basis of defending women’s

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

rights in Iraq and Afghanistan, Randell-Moon argues that the Howard Government has

developed a similar discourse of ‘feminised mainstream values’ that pits ‘mainstream’

white Australia as the defender of gender equality. Under this logic, in contrast to

Muslim societies, Australia has advanced away from pre-modern values towards a

secularism founded on reason, freedom and equality. These are the values threatened by

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho x INTRODUCTION

an aggressive Muslim minority determined to live according to an alternative, backward

belief system.

However, as Randell-Moon reminds us, the depiction of Australia as a secular society

elides its Christian heritage and moreover, the growing influence of a particular

politicised strain of Christianity within the corridors of power in this country. And of

course, the portrait of Australian values as founded on freedom and equality is only

possible when accompanied by a denial of the Australian nation’s own foundations on

colonial relations of oppression.

The intersection of secularism and ‘Australian values’ is further explored in Sophie

Sunderland’s innovative critique of the work of Spirituality Studies academic, David

Tacey. An advocate of what he terms ‘post-secular spirituality’, Tacey argues for a

spiritual renewal through an embracing of the Australian landscape and Aboriginal

cultures and has been taken up in popular debates around Australian national identity,

particularly under the Keating government. Where scholars have previously critiqued

Tacey’s constructions of Aboriginality, Sunderland turns her attention also to the

construction of whiteness in Tacey’s work. Through a close reading of Tacey’s work,

Sunderland demonstrates that the ‘empty’ whiteness posited by Tacey in fact functions

as a position of power in a neo-colonial politics which closes off a post-colonial ‘space-

between’. In this reading, the ‘spiritual’ emerges as a universalistic, Euro-centric and

Judaeo-Christian model which positions Aboriginal people as responsible for the

‘salvation’ of non-Aboriginal Australians.

Sunderland’s distinctive contribution to the debates around secularism, spirituality and

the nation stems from her engagement with the rapidly developing literature in

whiteness studies in Australia. Aileen Moreton-Robinson argues for a ‘new research

agenda’ (2006) which addresses issues of Indigenous sovereignty and the possessive

logic of whiteness beyond the ‘judicio-political framework’ usually assumed by legal

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

scholars and political theorists. Drawing on Foucault, Moreton-Robinson asks:

‘to what extent does White possession circulate as a regime of truth that

simultaneously constitutes White subjectivity and circumscribes the

political possibilities of Indigenous sovereignty. How does it manifest as

part of common-sense knowledge, decision-making and socially produced

conventions and signs?’ (2006: 389)

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho xi INTRODUCTION

Sophie Sunderland’s analysis of David Tacey’s ‘post-secular spirituality’ falls within

such a research agenda, exploring the ways in which an ‘embrace’ of Aboriginal

spirituality can serve to mask Indigenous sovereignties and to continue investment in

white possession of the nation.

Indigenous sovereignty is at the core of Fiona McAllan’s article on the politics of

‘community’ underpinning federal Indigenous Affairs policy as exemplified in Native

Title decisions and the 2007 ‘intervention’ in Northern Territory Aboriginal

communities. McAllan’s interrogation of the possessive logic of patriarchal whiteness

as analysed by Moreton-Robinson and Irene Watson is framed by the notion of

community as sharing incommensurable difference and productive disagreement

developed by Jean-Luc Nancy and later Linnell Seccomb. Through the Yorta Yorta

Native Title decision and the Northern Territory intervention McAllan traces the

continuing operations of colonial dispossession and property relations through the

Crown such that ‘Indigenous dispossession remains the groundwork’ of the law and the

nation. Crucial to this continuing dispossession are the difficulties in proving

‘community’ and of recognising communal ownership under common law.

In McAllan’s analysis, ‘it is clear that it is Indigenous relations with the land that

threatens possessive tenure and relations’ with the result that the possessive logic of

whiteness must deny ‘community’, for example by deriving a false paternal legitimacy

for the Northern Territory intervention by representing Indigenous communities as

lacking in self-determination and property entrepreneurialism. The ‘appropriative power

of possessive whiteness’, for McAllan, requires the denial of community across

incommensurable differences, imposing instead ‘the law of the same’.

Julie Browning shifts the focus from whiteness and paternalistic coercion to questions

of gender, violence and incarceration. Her paper analyses policies and practices of

immigration detention in Australia through the lens of hypermasculinity and the ‘state

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

of exception’ (Agamben 1998), arguing that ‘gender is a dimension to both the rationale

for detention and the forms of struggle against incarceration’. Browning draws on

extensive interviews with former detainees in describing immigration detention centres

as ‘a space of exaggerated masculinity’ in which ‘violence is entrenched and the

willingness to fight and the capacity for combat are measures of self-worth’. In the

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho xii INTRODUCTION

hypermasculinised space of immigration detention, protest actions, undertaken primarily

by male detainees, seek both to effect change in decision-making and also to reposition

the male detainee as an active masculine subject. For Browning, collective protest

among detainees in immigration detention occurs on the threshold between life and

death analysed by Agamben as ‘bare life’, yet suggests that the conditions of exception

are never total and, contra Agamben, struggle is not pointless.

Lana Zannettino’s paper places questions of immigration detention within debates

around hybridity and national identity which developed prior to the ‘war on terror’,

linking attention to asylum seekers reduced to ‘bare life’ back to questions around hijab

and everyday negotiations of identity. Zannettino analyses three well-known Australian

novels written for teenagers – Melina Marchetta’s Looking for Alibrandi (1992),

RandaAbdel-Fattah’s Does my Head Look Big in This? (2005) and Morris Gleitzman’s

Girl Underground (2004). Like Browning, Zannettino frames her discussion of

immigration detainees as described in Girl Underground through Agamben’s

theorisations of ‘bare life’ and the biopolitics of ‘the camp’. The novel documents

correspondence between the young white working-class protagonists and two young

asylum seekers held in the ‘extreme situation’ of detention.

The other two novels focus on young, ethnically-marked women and their negotiations

of hybrid identities – signified most clearly by Amal’s deliberation on whether, when,

where and how to wear hijab in Does my head look big in this? These protagonists are

confronted with processes of othering, belonging, inclusion and exclusion. Read

together, argues Zannettino, these novels provide an ‘implicit pedagogy of race relations

in Australia’. These books suggest hopeful possibilities for both hybrid identities, and,

in the face of politics of fear and ‘exception’, ‘collaborations of humanity’.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kevin Dunn and Bronwyn Winter for contributing their time

and expertise to a publications workshop for postgraduate and early career researchers

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

at the Not Another Hijab Row conference. Following the workshop six participants took

part in a ‘mentoring’ process whereby they were provided with feedback from senior

researchers prior to submitting papers for publication. The mentoring process was

supported by a small grant from the ARC Cultural Research network ECR/PG Node.

Many thanks to these mentors: Sharon Chalmers, Eva Cox, Jane Durie, Heather Goodall

and Penny O’Donnell. We would also like to thank Kiran Grewal, Lindi Todd and

Jonathan Marshall for their invaluable assistance in bringing this special issue to

fruition.

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho xiii INTRODUCTION

Bibliography

Abu Odeh, L (1993) ‘Post-colonial feminism and the veil: Thinking the difference’,

Feminist Review 43: 26-37.

Agamben, G (1998) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life Stanford University

Press, Stanford California

Ahmed, L. (1992) Women and Gender in Islam, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ayotte, Kevin J. and Husain, Mary E. (2005). Securing Afghan Women:

Neocolonialism, epistemic violence, and the rhetoric of the veil. NWSA Journal,

17(3), 112-133.

Bouma, G. D. and J. Brace-Govan (2000) ‘Gender and Religious Settlement: Families,

hijabs and identity’, Journal of Intercultural Studies 21(2): 159-175.

Butler, C. (1999) ‘Cultural Diversity and Religious Conformity: Dimensions of social

change among second-generation Muslim women’ in Ethnicity, Gender and

Social Change, R. Barot (ed), New York, Palgrave: 135-151.

Dreher, T (2006) Whose Responsibility?: Community anti-racism strategies in NSW

after September 11, 2001 UTS Shopfront Research Monograph Series No 3

Dreher, T. (2003) 'Speaking up and talking back: News media interventions in Sydney's

'othered' communities', Media International Australia incorporating Culture &

Policy, vol. November, pp. 121 -137 .

Dreher, T., Simmons, F. (2006) 'Australian Muslim Women's Media Interventions',

Feminist Media Studies, vol. 6 .

Dwyer, C. (2000) ‘Negotiating Diasporic Identities: Young British South Asian Muslim

Women’, Women's Studies International Forum 23(4): 475-486.

Ferguson, M.L. (2005) ‘“W” Stands for Women: Feminism and Security Rhetoric in the

Post-9/11 Bush Administration’, Politics and Gender 1(1): 9-38.

Ferguson, M. L. and L.J. Marso (eds) (2007) W Stands for Women: Hoe the George W

Bush Presidency Shaped a New Politics of Gender Duke University Press,

Durham and London

Ho, C. (2007) 'Muslim women's new defenders: Women's rights, nationalism and

Islamophobia in contemporary Australia', Women's Studies International Forum,

vol. 30, pp. 290 -298 .

Ho, C. & Dreher, T. (2006) 'Where has all the anti-racism gone?'. New Racisms/New

AntiRacisms conference, Sydney University

MacLeod, A. E. (1992) ‘Hegemonic Relations and Gender Resistance: The new veiling

as accommodating protest in Cairo’, Signs 17(3): 533-557.

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2006) ‘Towards a new research agenda? Foucault, Whiteness

and Indigenous sovereignty’ Journal of Sociology Vol 42 (4) pp 383 – 395

Perera, S. (2006) ‘Race Terror, Sydney, December 2005’ Borderlands ejournal Vol 5,

No 1

Poynting, S and G Noble, P Tabar, J Collins (2004) Bin Laden in the Suburbs:

Criminalising the Arab other Sydney Institute of Criminology Series, Sydney

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Dreher & Ho xiv INTRODUCTION

Samad, Y. (2004) ‘Muslim Youth in Britain: Ethnic to Religious Identity’, paper

presented to Muslim Youth in Europe: Typologies of Religious Belonging and

Sociocultural Dynamics, Edoardo Agnelli Centre for Comparative Religious

Studies, Turin.

Timmerman, C. (2000) ‘Muslim Women and Nationalism: The Power of the Image’,

Current Sociology 48(4): 15-27.

UMWA (United Muslim Women Association) (2005) ‘Pro-Hijab Campaign, online:

<http://www.mwa.org.au/prohijab.htm>, updated: 26 October 2005.

Young, I. M. (2007) ‘The Logic of Masculinist Protection: Reflections on the current

security state’ in Ferguson, M. L. and L.J. Marso (eds) W Stands for Women: Hoe

the George W Bush Presidency Shaped a New Politics of Gender, Duke

University Press, Durham and London, pp 115 – 140.

© 2007 Tanja Dreher & Christina Ho

Transforming Cultures eJournal Vol. 2 No. 1

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Turn To Whiteness: Race, Nation and Cultural Sociology: Ben WadhamDocument9 pagesThe Turn To Whiteness: Race, Nation and Cultural Sociology: Ben WadhamColton McKeePas encore d'évaluation

- Unruly Souls: The Digital Activism of Muslim and Christian FeministsD'EverandUnruly Souls: The Digital Activism of Muslim and Christian FeministsPas encore d'évaluation

- 2008 Racisms Conference ProceedingsDocument172 pages2008 Racisms Conference ProceedingsWaqar AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Newton Judith - Ms Representations Reflections On StudyningDocument12 pagesNewton Judith - Ms Representations Reflections On StudyningGabriela SarzosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Religion, the Secular, and the Politics of Sexual DifferenceD'EverandReligion, the Secular, and the Politics of Sexual DifferencePas encore d'évaluation

- Ashis Nandy - Return of The Sacred - 2007 LectureDocument20 pagesAshis Nandy - Return of The Sacred - 2007 Lecturephronesis76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Talking Gender: Public Images, Personal Journeys, and Political CritiquesD'EverandTalking Gender: Public Images, Personal Journeys, and Political CritiquesPas encore d'évaluation

- What'S Queer About Queer Studies Now?Document18 pagesWhat'S Queer About Queer Studies Now?Aleqs GarrigózPas encore d'évaluation

- Blackcentricity: How Ancient Black Cultures Created Civilization. Revealing the Truth that White Supremacy DeniedD'EverandBlackcentricity: How Ancient Black Cultures Created Civilization. Revealing the Truth that White Supremacy DeniedPas encore d'évaluation

- From TichelsDocument11 pagesFrom Tichelsaustin.rogers3531Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dialogic Moments: From Soul Talks to Talk Radio in Israeli CultureD'EverandDialogic Moments: From Soul Talks to Talk Radio in Israeli CultureÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- Jin Haritaworn (Chapter-3)Document35 pagesJin Haritaworn (Chapter-3)Charlie Abdullah HaddadPas encore d'évaluation

- Towards an Ethics of Community: Negotiations of Difference in a Pluralist SocietyD'EverandTowards an Ethics of Community: Negotiations of Difference in a Pluralist SocietyPas encore d'évaluation

- Pride and Prejudice PaperDocument29 pagesPride and Prejudice PaperMax LederPas encore d'évaluation

- Gill, R The Sexualization of CultureDocument16 pagesGill, R The Sexualization of CultureMayra SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Religion and Public Discourse in an Age of Transition: Reflections on Bahá’í Practice and ThoughtD'EverandReligion and Public Discourse in an Age of Transition: Reflections on Bahá’í Practice and ThoughtPas encore d'évaluation

- Eck, Religious PluralismDocument34 pagesEck, Religious Pluralismtheinfamousgentleman100% (1)

- Hidden Heretics: Jewish Doubt in the Digital AgeD'EverandHidden Heretics: Jewish Doubt in the Digital AgeÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (1)

- KNOWLES Caroline Theorizing Race and Ethnicity Contemporary Paradigms and PerspectivesDocument20 pagesKNOWLES Caroline Theorizing Race and Ethnicity Contemporary Paradigms and PerspectivesJonathan FerreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Felt TheoryDocument23 pagesFelt TheoryMaansi ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- La Conversation Fracturée: Concepts of Race in AmericaD'EverandLa Conversation Fracturée: Concepts of Race in AmericaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bracke - Fadil (2012) Inglés PDFDocument21 pagesBracke - Fadil (2012) Inglés PDFJo KuninPas encore d'évaluation

- DavidBos2015Likewise ReligionsandSame SexSexualitiesDocument9 pagesDavidBos2015Likewise ReligionsandSame SexSexualitiesSan Francisco TlalcilalcalpanPas encore d'évaluation

- Jonathan Sacks EDAH Journal Dignity of DifferenceDocument15 pagesJonathan Sacks EDAH Journal Dignity of DifferencedavidshashaPas encore d'évaluation

- Relativism and Religion: Why Democratic Societies Do Not Need Moral AbsolutesD'EverandRelativism and Religion: Why Democratic Societies Do Not Need Moral AbsolutesPas encore d'évaluation

- WJIR0805037Document7 pagesWJIR0805037Titilayomi EhirePas encore d'évaluation

- Leveling Crowds: Ethnonationalist Conflicts and Collective Violence in South AsiaD'EverandLeveling Crowds: Ethnonationalist Conflicts and Collective Violence in South AsiaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Religion and IdentityDocument20 pagesReligion and IdentityMaricela R DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- "There Is Nothing Honourable' About Honour Killings''Document47 pages"There Is Nothing Honourable' About Honour Killings''angelustestica.maPas encore d'évaluation

- No Sex Please, We 'Re AmericanDocument11 pagesNo Sex Please, We 'Re AmericanVictor Hugo BarretoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lila Abu - Lughod The Debate About Gender, Religion and RightsDocument11 pagesLila Abu - Lughod The Debate About Gender, Religion and RightsClara Gonzalez CragnolinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Moreton, White WomanDocument12 pagesMoreton, White WomanHarrison Delaney100% (1)

- "It Depends How You're Saying It": The Complexities of Everyday RacismDocument17 pages"It Depends How You're Saying It": The Complexities of Everyday Racismbelovaalexandra25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Culture Against Society: F. Allan HansonDocument5 pagesCulture Against Society: F. Allan HansonBently JohnsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijels-34 Jan-Feb 2022 PDFDocument7 pagesIjels-34 Jan-Feb 2022 PDFIJELS Research JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender, Religion, and SpiritualityDocument91 pagesGender, Religion, and SpiritualityOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender, Religion, and SpiritualityDocument91 pagesGender, Religion, and SpiritualityOxfam100% (1)

- Gender, Religion, and SpiritualityDocument91 pagesGender, Religion, and SpiritualityOxfam100% (3)

- Gender, Religion, and SpiritualityDocument91 pagesGender, Religion, and SpiritualityOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethio 0066-2127 2015 Num 30 1 1580Document10 pagesEthio 0066-2127 2015 Num 30 1 1580Fiyori GebremedhinPas encore d'évaluation

- Rogers Brubaker-Grounds For Difference-Harvard University Press (2015) PDFDocument236 pagesRogers Brubaker-Grounds For Difference-Harvard University Press (2015) PDFKoko CireasaPas encore d'évaluation

- Muslim LGBT ReportDocument70 pagesMuslim LGBT ReportLGBT Asylum News67% (3)

- Politics of Identity and The Project of Writing History in Postcolonial India - A Dalit CritiqueDocument9 pagesPolitics of Identity and The Project of Writing History in Postcolonial India - A Dalit CritiqueTanishq MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- AnnotatedbibliographyDocument7 pagesAnnotatedbibliographyapi-451558425Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bardwell-Jones and McLaren, Introduction - To - Indigenizing - ADocument17 pagesBardwell-Jones and McLaren, Introduction - To - Indigenizing - AgabyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bell HooksDocument11 pagesBell HooksSonitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Polygyny, Family and Sharafat Discourses Amongst North Indian Muslims, Circa 1870-1918Document38 pagesPolygyny, Family and Sharafat Discourses Amongst North Indian Muslims, Circa 1870-1918Usman AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng, Halberstam, Muñoz - What's Queer About Queer Studies NowDocument19 pagesEng, Halberstam, Muñoz - What's Queer About Queer Studies NowPaige BeaudoinPas encore d'évaluation

- GUPTA IntimateDesiresDalit 2014Document28 pagesGUPTA IntimateDesiresDalit 2014Rupsa NagPas encore d'évaluation

- Race Religion and Riots The RacializatioDocument18 pagesRace Religion and Riots The RacializatioJohana MahratPas encore d'évaluation

- 255-Article Text-303-1-10-20190220Document7 pages255-Article Text-303-1-10-20190220oluwafemi EmmanuelPas encore d'évaluation

- Questions of ModernityDocument258 pagesQuestions of ModernityGarrison DoreckPas encore d'évaluation

- Identity Multicultural StudiesDocument311 pagesIdentity Multicultural Studieswaldhorn33Pas encore d'évaluation

- CircumcisionDocument12 pagesCircumcisionCamila OrozcoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dialogue of Democratic EducationDocument22 pagesThe Dialogue of Democratic Educationkanga_rooPas encore d'évaluation

- Learner Autonomy in A NutshellDocument12 pagesLearner Autonomy in A Nutshellahmdhassn100% (1)

- Wiley Ontario Institute For Studies in Education/University of TorontoDocument8 pagesWiley Ontario Institute For Studies in Education/University of Torontokanga_rooPas encore d'évaluation

- Excellence of Qiyamullaili Complete PackageDocument121 pagesExcellence of Qiyamullaili Complete Packagekanga_rooPas encore d'évaluation

- Nusaybah Bint KabDocument3 pagesNusaybah Bint Kabkanga_rooPas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship With Non-MuslimsDocument94 pagesRelationship With Non-Muslimskanga_rooPas encore d'évaluation

- Face Reading - EarDocument4 pagesFace Reading - Earkenny8787100% (1)

- Social Issues and Threats Affecting Filipino FamiliesDocument24 pagesSocial Issues and Threats Affecting Filipino FamiliesKarlo Jayson AbilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy Welcome Back One PagerDocument2 pagesAnatomy Welcome Back One PagerLexie DukePas encore d'évaluation

- The Relationship Between Theoretical Concepts and ArchitectureDocument17 pagesThe Relationship Between Theoretical Concepts and ArchitectureHasanain KarbolPas encore d'évaluation

- Nonviolent Communication Assignment 1Document4 pagesNonviolent Communication Assignment 1mundukuta chipunguPas encore d'évaluation

- Methodology and Meaning: Improving Relationship Intelligence With The Strength Deployment InventoryDocument20 pagesMethodology and Meaning: Improving Relationship Intelligence With The Strength Deployment InventorykarimhishamPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Influencing Purchase Intention in Online ShoppingDocument14 pagesFactors Influencing Purchase Intention in Online ShoppingSabrina O. SihombingPas encore d'évaluation

- Blind Ambition in MacbethDocument3 pagesBlind Ambition in MacbethHerlin OctavianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 5 Critical Thinking 2Document7 pagesModule 5 Critical Thinking 2api-265152662Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dna Mixture Interpretation: Effect of The Hypothesis On The Likelihood RatioDocument4 pagesDna Mixture Interpretation: Effect of The Hypothesis On The Likelihood RatioIRJCS-INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF COMPUTER SCIENCEPas encore d'évaluation

- Argument IssueDocument2 pagesArgument IssueihophatsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ted Hughes' Full Moon and Little FriedaDocument2 pagesTed Hughes' Full Moon and Little FriedaRadd Wahabiya100% (2)

- The Concept of GURU in Indian Philosophy, Its Interpretation in The Soul of The World' Concept in - The Alchemist - Paulo CoelhoDocument8 pagesThe Concept of GURU in Indian Philosophy, Its Interpretation in The Soul of The World' Concept in - The Alchemist - Paulo Coelhon uma deviPas encore d'évaluation

- Actividad 1 - Pre Saberes INGLES 1 PDFDocument8 pagesActividad 1 - Pre Saberes INGLES 1 PDFAlexandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Alcadipani 2017Document17 pagesAlcadipani 2017Evander Novaes MoreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Activity 1: Checking Out Local Art MaterialsDocument2 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Activity 1: Checking Out Local Art MaterialsZharina Villanueva100% (2)

- Object-Oriented Analysis and Design (OOAD)Document35 pagesObject-Oriented Analysis and Design (OOAD)Chitra SpPas encore d'évaluation

- AP Human Geography Chapter 1 Basic Concepts VocabularyDocument3 pagesAP Human Geography Chapter 1 Basic Concepts VocabularyElizabethPas encore d'évaluation

- Similarities Between Hinduism and IslamDocument97 pagesSimilarities Between Hinduism and IslamUsman Ghani100% (2)

- Intercultural Personhood and Identity NegotiationDocument13 pagesIntercultural Personhood and Identity NegotiationJoão HorrPas encore d'évaluation

- Prayers of The Last ProphetDocument227 pagesPrayers of The Last ProphetkhaledsaiedPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Peter Student's GuideDocument25 pages1 Peter Student's GuideAnonymous J4Yf8FPas encore d'évaluation

- Grice's Flouting The Maxims: Example 1Document2 pagesGrice's Flouting The Maxims: Example 1Learning accountPas encore d'évaluation

- Command and Control Multinational C2Document7 pagesCommand and Control Multinational C2Dyana AnghelPas encore d'évaluation

- Vidler - Architecture's Expanded FieldDocument8 pagesVidler - Architecture's Expanded FieldNelson Stiven SánchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Astrology Services by Upma ShrivastavaDocument7 pagesAstrology Services by Upma ShrivastavaVastuAcharya MaanojPas encore d'évaluation

- Restricted Joint Chiefs of Staff Manual 3314.01A Intelligence Planning PDFDocument118 pagesRestricted Joint Chiefs of Staff Manual 3314.01A Intelligence Planning PDFSHTF PLANPas encore d'évaluation

- Fiitjee Rmo Mock TestDocument7 pagesFiitjee Rmo Mock TestAshok DargarPas encore d'évaluation

- ISC Physics Project Guidelines PDFDocument4 pagesISC Physics Project Guidelines PDFSheetal DayavaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Non Experimental Research 1Document22 pagesNon Experimental Research 1Daphane Kate AureadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsD'EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (387)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsD'EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1424)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryD'EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (14)

- The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveD'EverandThe Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (384)

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusD'EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (22)

- Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindD'EverandLucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (54)

- Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureD'EverandAbolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (4)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveD'EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (22)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsD'EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (16)

- Silent Tears: A Journey Of Hope In A Chinese OrphanageD'EverandSilent Tears: A Journey Of Hope In A Chinese OrphanageÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (29)

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityD'EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (56)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateD'EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (18)

- Crones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenD'EverandCrones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenÉvaluation : 2.5 sur 5 étoiles2.5/5 (3)

- Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationD'EverandDecolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (22)

- An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United StatesD'EverandAn Indigenous Peoples' History of the United StatesÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (349)

- AP Human Geography Premium, 2024: 6 Practice Tests + Comprehensive Review + Online PracticeD'EverandAP Human Geography Premium, 2024: 6 Practice Tests + Comprehensive Review + Online PracticePas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityD'EverandGender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (317)

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- The Myth of Equality: Uncovering the Roots of Injustice and PrivilegeD'EverandThe Myth of Equality: Uncovering the Roots of Injustice and PrivilegeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (17)

- The End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our SocietyD'EverandThe End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our SocietyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (126)