Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Life in Brackets Minority Christians and

Transféré par

syeduop3510Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Life in Brackets Minority Christians and

Transféré par

syeduop3510Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

international journal on minority and

group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

brill.com/ijgr

Life in Brackets: Minority Christians

and Hegemonic Violence in Pakistan

Amalendu Misra

Senior Lecturer, Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion

Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK

a.misra@lancaster.ac.uk

Abstract

This article focusses on the Christian minority in Pakistan, and postulates that their

“crisis condition” can be explained within a set pattern of rules. Within that frame-

work, it examines three separate, but interrelated theoretical positions: The rising level

of Islamic radicalism and consequent attack on minority Christians needs to be placed

within the framework of a “thick” and “thin” view of religion; 2. the select “targeting” of

a minority and stirring up of sectarian conflict is the outcome of a clearly thought out

framework of hegemonic violence; and 3. the conscious process of “scapegoating” that

establishes the majority-led in-group and out-group narrative leading to the castiga-

tion and persecution of the marginal group. The last two sections examines the scope

of external intervention on behalf of this beleaguered community. It goes on to assess

the coping strategies of the Christians in the face of mounting Sunni Muslim extremist

violence.

Keywords

Christians – majority – minority – Pakistan – radical Islam – Sunni Muslim – violence

* The author is grateful to the anonymous reviewers of this journal for their very helpful con-

structive comments. He is also indebted to Nawar Kassomeh for alerting me to the complex

narratives surrounding Shi’ia-Sunni sectarian violence in Pakistan.

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02202002

158 Misra

1 Introduction

Sectarian violence in Pakistan can be divided into two categories. The first one

is intra-religious in nature. It is generally played out between various strands

of Islam i.e., Sunni-Shi’a, Sunni-Ahmadiya, as well as between the Sunnis

themselves. The second category relates to sectarianism between Islam and

non-Islamic minorities (Christians, Hindus, Parsis, Sikhs). In contemporary

Pakistan, both strands of sectarian violence appear common. This study, how-

ever, focuses on the second category which is primarily inter-religious in

nature. Within this category it seeks to examine the dimensions of sectarian

violence experienced by one specific non-Muslim minority, Christians.

A precise Christian population in contemporary Pakistan is difficult to

establish.1 According to the official government figures based on a 1998 census,

Pakistan has nearly 2.1 million Christians; constituting some 1.6 per cent of the

total population.2 The figures released by the United States Central Intelligence

Agency (cia) in 2013, however, placed Pakistan’s Christians at 3.5 million or 1.8

per cent of the total share of population.3 Of these, 60 per cent are Catholics

and the remaining 40 per cent belong to various Protestant denominations.

Their geographic spread is countrywide. They live in small pockets from the

Punjab in the East to Baluchistan in the West, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in

the North to Sind in the South. Their biggest concentration, however, is in the

province of Punjab.

As a minority in an overwhelming Islamic nation, Christians were regarded

as integral to the fabric of this new state. At its inception, under the original

constitutional provisions, they were guaranteed equal rights alongside their

Muslim counterparts.4 As a model minority,5 no other non-Muslim religious

community has contributed more to the social sector development of Pakistan

1 A.K. Raina, ‘Minorities and Representation in a Plural Society: The Case of the Christians in

Pakistan’, 37(4) South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies (2014) p. 10.

2 A.S. Ahmed, ‘Pakistan’s Persecuted Christians’, The New York Times, 23 December 2013, p. 9.

3 The World Factbook: Pakistan, cia, <www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

geos/pk.html>, visited on 29 September 2014.

4 Ahmed, supra note 2, p. 9.

5 Although not a homogenous religious group, Christians belonging to various denominations

in the country have always been committed to the Pakistani nation. As the talk of end of

British rule became apparent and there was a reckoning that the former British colony would

be divided into two parts, the Christians living in the region that now consists of modern day

Pakistan put their lot on the side of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and his political party, the All

India Muslim League, that called for a separate independent state for Muslims.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 159

than the Christians have.6 It is worth mentioning in this context, that Pakistan’s

first constitution was “penned by a Catholic, Justice A.R. Cornelius”.7

Yet, in recent decades, direct and indirect egregious majoritarian violence

against Christians have become persistent and widespread. This violence is

countrywide in its dynamics and it is rural as well as urban in nature. It involves

both ad hoc i.e., apparently spontaneous acts of attack, as well as organised

anti-Christian purges in which government authorities, local and national,

collude either directly or by omission.8 In fact, both formal and informal

discrimination against minorities (which includes all non-majoritarian and

non-Sunni minorities) has gone hand in hand; one has encouraged and deep-

ened the other.9

Although Islam was the raison d’etre behind Pakistan’s emergence as an

independent nation, the new state nonetheless championed equality between

different faiths. Yet that commitment was short lived. Since the 1970s, Pakistan

has been experiencing a steady erosion of tolerance against its minorities.

While focussing on Pakistan in its 2013 Annual Report, the United States

Commission on International Religious Freedom, for instance, specified more

than 200 attacks on minority religious groups in the country and reported 1,800

casualties resulting from religion-related violence (one of the highest in the

world).10 In its report published towards the end of 2013, the Minority Rights

Group International (mrg) underscored that Pakistan was at the top of its

“Peoples under Threat” global rankings.11 Similarly the Pew Research Centre’s

report for the same period highlighted that “Pakistan had the highest level of

social hostilities involving religion”.12

6 R.B. Rais, ‘Islamic Radicalism and Minorities in Pakistan’, in S.P. Limaye et al. (eds.),

Religious Radicalism and Security in South Asia (Asia Pacific Centre for Security Studies,

Honolulu, hi, 2004) p. 461.

7 Raina, supra note 1, p. 6.

8 S. Gregory and S.R. Valentine, Pakistan: the Situation of Religious Minorities, (unhcr,

New York, 2009) p. 18.

9 Rais, supra note 6, p. 463.

10 United States Commission on International Religious Freedom – 2013 Annual Report. <www

.uscirf.gov/reports-briefs/annual-report/2013-annual-report>, visited on 02 May 2013.

11 Minority Rights Group International, mrg Condemns Cttack on Christians in Pakistan and

Calls for Increased Protection of Minorities in the Country, 23 September 2013 <www

.minorityrights.org/12069/press-release/mrg-condemns-attack-on-christia…>, visited on

17 May 2014.

12 Pew Research: Religion and Public Life Project, Religious Hostilities Reach Six-Year High

14 January 2014 <www.pewforum.org/2014/01/14/religious-hostilities-reach-six-year-high/>,

visited on 02 May 2014.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

160 Misra

What explains this level of violence and loss of tolerance? In order to extri-

cate a credible answer to this question we have to (a) interrogate the nature of

Pakistani politics; and (b) evaluate the majority community’s disposition

towards its minorities.

As Max Weber argued, “the more a religion acquires the aspects of a

‘communal religion’ (gemeinde-religiositat), the more political circumstances

co-operate with it for its further consolidation”.13 A cursory backward glance

into Pakistan’s modern history suggests that in order to raise their status quo

ante, successive regimes have consistently engaged in anti-minority discourse

and policy planning. The first coordinated large-scale attempt to squeeze the

minorities from the public place and create a nationwide dissent against them

was unveiled in the early 1970s. The Pakistan People’s Party (under the leader-

ship of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto) nationalised schools and colleges and introduced

laws and policies that encouraged discrimination against the country’s minori-

ties.14 Although there was a slow and steady erosion of tolerance towards the

minorities since the 1950s, Bhutto’s intervention was the first sustained official

attempt to ostracise all non-Muslim minorities from the national mainstream.

In one of the most ‘crippling moves against minorities’,15 Bhutto “liberally

traded minority rights to the Islamists for an ever-elusive political stability”.16

The roots of current majoritarian sectarianism in Pakistan can be traced to

the manipulation of Islam by General Zia ul-Haq. General Zia ul-Haq, who

served as President of Pakistan from 1977–1988 and replaced Bhutto, was very

open about his commitment to the creation of a majoritarian Sunni-dominated

state; even if that meant the erosion of secular credentials and undermining of

the minorities. Interestingly, in an interview with The Economist magazine

shortly after taking over power in a military coup in 1981, he put forward the

argument that “Pakistan is like Israel, an ideological state … Take out Judaism

from Israel and it will fall like a house of cards … Take Islam out of Pakistan and

make it a secular state; it would collapse”.17

Notwithstanding this supposed political expediency behind the construc-

tion and preservation of an ideological nation state, General Zia ul-Haq’s Sunni

13 M. Weber, The Sociology of Religion (Methuen & Co., London, 1971) pp. 224–225.

14 The then-Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto is reported to have said “I have said

quite clearly that Islam is our faith. Islam is our religion and the basis of Pakistan and

we are Muslims”. S.S. Panwhar (ed.), Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: The Politics of Charisma

<www.ebookbrowsee.net/zulfikar-ali-bhutto-politics-of-charisma-pdf-d56274771>

visited on 17 September 2012.

15 Rais, supra note 6, p. 456.

16 Raina, supra note 1, p. 6.

17 F. Devji, Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea (Hurst, London, 2013) p. 4.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 161

nation-building project was a shrewd attempt at building a popular base for his

regime. General Zia “pushed covert secular laws into religious ones, installing

Shari’a courts and enacting anti-blasphemy statutes”.18 In view of some critics,

this project was introduced specifically to please religious parties supporting

his martial law.19 Being an usurper of power and devoid of a democratic man-

date, General Zia turned to the right wing Islamic elements for support. His

attempt to create an Islamic polity and society was primarily an attempt at

regime consolidation. General Zia’s use of Islam as a tool to legitimise his rule

unveiled the process of Sunnification of Pakistan and was a turning point in

the history of the country’s minorities.20 According to historian Ian Talbot,

General Zia’s rule represented the ‘end of state neutrality’21 toward minority

groups and courting of Sunni sectarianism.

During the 1980s, a wave of Islamisation programme unveiled a country-

wide self-styled “guardians of religion” movement that took upon itself

the responsibility to forcibly convert the country’s minorities including the

Christians. And whenever there was resistance to it from the minorities, they

were swiftly put down by blatant Sunni majoritarian violence – often at the

approval of the regime. Needless to add, persecution of religious minorities

increased with General Zia ul-Haq’s Islamisation project.

From the 1990s onward, various military and civilian governments have pur-

sued a pro-Sunni Islam policy – an undertaking that permeates all walks of life

including the educational system. In the last decade, children in most state-

run educational establishment were expected to recite everyday “Pakistan ka

matlab kya? La illaha illala! (What is the meaning of Pakistan? There is no god

but Allah!”22

According to the Brussels-based International Crisis Group (icg), sectarian

conflict in Pakistan is the direct consequence of state policies of Islamisation

of secular democratic forces. In its view, instead of empowering liberal, demo-

cratic voices, successive governments have co-opted the religious right and

18 J. Kaleem, ‘Religious Minorities in Pakistan Struggle but Survive Amid Increasing

Persecution’, Huffington Post, 10 February 2014, p. 7.

19 Rais, supra note 6, p. 456.

20 M. Waseem et al., Dilemmas of Pride and Pain: Sectarian Conflict and Conflict Trans

formation in Pakistan, Religion & Development Working Paper 48, (International

Development Department, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, 2010) p. 7.

21 I. Talbot, ‘Religion and Violence: The Historical Context for Conflict in Pakistan,’ in R. John

& R. King (eds.), Religion and Violence in South Asia – Theory and Practice (Routledge,

London, 2007) pp. 154–172.

22 P. Hoodbhoy, ‘Jinnah and the Islamic State: Setting the Record Straight’, 42:32 Economic

and Political Weekly (2007) p. 3300.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

162 Misra

continue to rely on it to create a firm base among hardliners, which allows

them to maintain their hold on power.23

For instance, none of the post-independent government in Pakistan has

done much to rein in radical Sunni groups who glorify open sectarian vio-

lence. According to one critic, Pakistan “does not have any law that can stop

extremists from changing the slogan ‘Kafir kafir jo na mane woh bhee kafir’”

(infidels, infidels, those who are not believers (i.e., in Sunni Islam) are infidels

too). Consequently, these infidels are ‘wajibul qatl’ (deserving of legitimate

killing).24

While the “othering” of the minorities in Pakistan by the Sunni majority has

its origin in political manipulation of religious identity, there are other impor-

tant economic factors that provide a basis to this majoritarian hegemony. This

is very much evident in the context of Sunni-Shi’ia sectarian divide. Many

Shi’ias in the country belong to an affluent class and are powerful landlords.

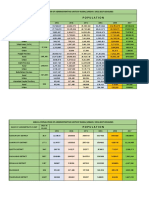

1400

1200

1000

Incidents

800

Killed

600

Injured

400

Linear (Killed)

200

0

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

Figure 1 Sectarian violence in Pakistan ( January 1989–March 2014)

Source: South Asian Terrorism Portal25

23 International Crisis Group, Pakistan: The Militant Jihadi Challenge, Asia Report, No 164

(International Crisis Group, Brussels, 2009).

24 M. Shehzad, ‘The State of Islamic Radicalism in Pakistan’, 37: 2 Strategic Analysis (2013)

pp. 186–192.

25 South Asian Terrorism Portol, Sectarian Violence in Pakistan, <www.satp.org/satporgtp/

countries/pakistan/database/sect-killing.htm>, visited on 1 June 2014.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 163

They often own large estates around Jhang in the Punjab, controlling their

Sunni and Shi’ia clients.26

Consequently, Sunni attempts to break the economic dominance of Shi’ia

elite in the Punjab in the past have become an important factor in the consoli-

dation of majoritarian sectarian violence across the country. Such is the feroc-

ity of this pointed majoritarian aggression that some critics have come to

comment that the Shi’ias have two choices (a) sit and wait for a messiah to

appear to rescue them; (b) relocate to a Shi’ia exclusive enclave elsewhere.27

The persecution of minorities in the hands of hard-line Sunnis in Pakistan

in recent years can also be explained within an archaic religio-juridical con-

text. From the 1990s until now, persecution of minorities has taken a new turn

within the context of ‘blasphemy law’. While the original remits of blasphemy

law was an institutional framework designed to uphold the majority faith from

attacks by rivals – more recently it has been appropriated by individuals and

radical Islamists seeking to settle their own private intolerance against various

Islamic sects and non-Muslims in the country.28

As independent studies have consistently suggested “because minorities are

demographically, socio-economically and politically depressed, blasphemy is

often used by the local power elite, mainly feudal landlords, as a pretext to

appropriate their labour, land and women”.29 The most damning aspect of this

hegemonic design is that the controversial blasphemy law permits any Muslim

(read Sunni Muslim in this context) to accuse a person of insulting Islam with-

out having to produce the required evidence that will stand up in a court.30

According to the 2013 Human Rights Watch Country Report on Pakistan

“abuses were rife under the country’s blasphemy law, which is used by the

Sunni majority against religious minorities, often to settle personal disputes”.31

In view of human rights campaigners, this strict law against defaming Islam is

often misused by unscrupulous individuals to settle personal grudges against

26 E. Murphy, The Making of Terrorism in Pakistan: Historical and Social Roots of Extremism

(Routledge, New York, 2013) p. 27.

27 M. Haider, ‘Time for Shi’ias to leave Pakistan,’ The Dawn, 17 February 2013, p. 11.

28 While no one has been executed under the blasphemy law, since 2001 approximately

32 people — including two judges — have been slain by vigilantes for expressing their

opposition to this “draconian” Islamic stricture.

29 Raina, supra note 1, p. 4.

30 S. Mohsin, ‘Tackling Religious Intolerance and Violence in Pakistan’, cnn, 24 September

2013, p. 8.

31 Human Rights Watch, Country Report: Pakistan, <www.hrw.org/world-report/2014/

country-chapters/pakistan>, visited on 1 May 2014.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

164 Misra

minorities,32 and is particularly common in the context of Christians. In

August 2013, a coordinated attack against Christians in the poor suburbs of

Islamabad led to 400 families fleeing their homes and neighbourhoods. It was

later found that the ringleader of this mob, local cleric Khalid Chisti, “had fab-

ricated evidence in order to rid the neighbourhood of Christians”.33

On balance one must stress that a section of the judiciary and the political

establishment have come to recognise the threat of appropriation of the blas-

phemy law and its remits by self-serving individuals and a given religious con-

stituency. Evaluating the role of judiciary, we find while most of the blasphemy

charges against Christians (including one against a 14 year old child with Down

syndrome) have led to the death sentence by lower courts, though these

charges have been overturned by the higher courts due to lack of evidence.34

Similarly, in an effort to curb the abuse of the provisions stipulated within

blasphemy law and to stem the rising tide of extremism against minorities, two

prominent politicians sought to amend this controversial law. However, there

were countrywide protests and the politicians in the forefront of this drive (the

governor of the Punjab province and the federal minister for minority affairs)

were both assassinated by radical Islamic extremists for even considering such

a move. In addition to these high profile murders, ordinary Pakistanis paid

their lives to voice their concern on majoritarian religious intolerance. Rashid

Rehman, a lawyer and regional coordinator for the Human Rights Commission

of Pakistan (hrcp), was gunned down by assailants (on 8 May 2014 in Multan).

Lawyer Rehaman’s guilt surrounded his defence of a university lecturer who

had been framed on charges of blasphemy.35

Unsurprisingly, these biased and repressive policies and the perpetuation

majoritarian purge have patently disadvantaged the minorities. However, it is

the Christians who have been disproportionately affected by the lopsided

institutional policies and fraying of tolerance on the part of the majority. Since

2000, Pakistan’s Sunni majority Muslims have subjected Christians to wave

after wave of systemic unprovoked assault. Arson attacks, lynching, mob vio-

lence, demonisation through Friday religious prayers, rape of Christian women,

kidnapping of Christian girls and forcing their conversion to Islam, land grab-

bing, destruction of Christian religious buildings, public humiliation,

32 F. Fiaz, ‘Christians in Pakistan sentenced to death over a text’, The Telegraph, 7 April 2014,

p. 11.

33 Human Rights Watch, supra note 31.

34 For a detailed discussion, see, Sawan Masih: Pakistani Christian Gets Death Penalty for

Blasphemy’, <www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-26781731>, visited on 30 April 2014.

35 ‘Rashid Rehman shooting: Pakistan Human Rights Lawyer Who Received ‘Death Threats’

over High Profile Blasphemy Case Is Shot Dead’, The Independent, 8 May 2014.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 165

k idnapping, extra judicial killing, false accusations, eviction and target killings

are some of the ordeals that Christians go through on a regular basis.

If this catalogue of persecution was not enough, there have also been fre-

quent petitions to the country’s highest judicial body, the Supreme Court by a

key political party Jamait Ulema-e-Islam to ban the Bible; in effect disenfran-

chise the Christians of their religion and by extension their primary religious

identity. This unrelenting Islamisation of society and state, according to one

critic, “appears to have acquired autonomy and self-direction; Pakistan’s liberal

elites are unable to resist it, much less reverse it”.36

2 Thinning of Tolerance

A cursory glance at the history of the Christian community in Pakistan sug-

gests that they have had a relatively secure and peaceful existence alongside

the majority of Muslims compared to their other minority counterparts, i.e.,

Hindus.37 In fact, despite the state-sponsored Islamisation of the public space

project (that began in earnest in the 1980s) Christians were mainly left to their

own affairs. However, it is in the past three decades that their lives, culture and

religion have come under relentless majoritarian scrutiny. Following that, they

have been condemned to hegemonic violence. What is the basis of this majori-

tarian intolerance? What sustains this new narrative of violence?

I wish to argue that this conflict dynamic has a lot to do with a specific imagi-

nation process affecting the country’s radical Sunni Islamists in relation to

Christians. This particular imagination is best explained within the framework

of “thick” and “thin” view of “the other”. In social anthropology, political theory

and religious studies, the identification of a given group or ideology by its coun-

terpart at times is done through the particular process of attribution.38 Thick

and thin commitment to religion is often measured within the quantitative and

qualitative markers. While some critics hold that thick commitment to a religion

(and consequently the level of intolerance it displays towards others who are

outside it) is best explained in the context of quantity – i.e., greater the number,

greater the destabilising power of religion39 others take a directly opposite view.

36 Raina, supra note 1, p. 4.

37 Cf., T. Gabriel, Christian Citizens in an Islamic State: The Pakistan Experience (Ashgate,

London, 2007).

38 For a detailed discussion see, C. Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (Basic Books,

New York, 1974); M. Walzer, Thick and Thin: Moral Argument at Home and Abroad

(University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, in, 1994).

39 On this point see, A. Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Harvard University Press, Cambridge,

ma, 2002).

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

166 Misra

To those belonging to the other school of thought, it is the quality of com-

mitment to religion that is the key to determining its followers’ level of toler-

ance and intolerance towards others.40 In view of these critics,

approaching the issue of religion and violence by looking at the quantity of

religious commitment – more religion, more violence, less religion, less

violence – is unsophisticated and mistaken. The most relevant fact is rather,

the quality of religious commitments within a given religious tradition.41

Therefore, given that all religions profess fellow feeling, peace and universal

brotherhood, a thick commitment to a religion or unyielding loyalty to a par-

ticular religious outlook, in fact, can be “order restoring and life affirming”.42

Viewed within this framework, while a thick adherence to religion would imply

greater communal harmony, a qualitative erosion or thinning of the original

precepts of religion would find manifestation in inter-communal intolerance.

Although founded as a homeland for Muslims, Pakistan nonetheless had its

basis in a “thick” view of Islam. Consequently, while Pakistan rejoiced the fact

of being a cherished homeland for Muslims, it simultaneously celebrated

its identity as a protector of various other faiths. If anything, it is the “thick”

commitment to a religion that espouses values such as fellow feeling, solidar-

ity and tolerance that was something central to the founder of Pakistan

Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s thinking.43 Given that foundational aspiration, it is

agreed upon by generations of scholars that “Pakistan’s founders envisioned a

secular-liberal democratic Pakistan with equal citizenship, and popular sover-

eignty that was identity agnostic”.44

However, it is the departure from that original “thick” view of religion towards

a “thin,” but zealous understanding of Islam vis-à-vis other co-religionists in the

country that has fostered socio-religious discord, inter-group hatred and inter-

communal violence. Accentuation of this thinness has been made possible

owing to (a) the narrow parochial vision of the state in matters of minority

40 See, M. Volf, Christianity and Violence (University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons,

Philadelphia, 2002).

41 Ibid., pp. 4–5.

42 M. Juergensmeyer, Terror in the Mind of God – The Global Rise of Religious Violence

(University of California Press, Berkeley, ca, 2000) p. 242.

43 See, A. Jalal, The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the Demand for Pakistan

(Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1985); F. Shaikh, Making Sense of Pakistan

(Columbia University Press, New York, 2009). Unsurprisingly, the new nation state sym-

bolised this commitment towards minorities by placing a white strip in the national flag

(against an overwhelming green strip representing Islam).

44 Raina, supra note 1, p. 4.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 167

issues; (b) the predominance of radical interpretation of Islam. Given this dis-

position, certain religious convictions have been misused to castigate the

minority community and use this thin understanding of religion to legitimise

violence against it.

If thinness refers to the decaying of original moral, ethical and secular

values among a certain community, what are the indicators that highlight that

detrimental development?

One can tease out three strands of thin religiosity in the context of Pakistan.

The first one relates to the creation of a binary divide between who is a true

Pakistani and who is not while using the compass of religion. This referential

framework, again, is based on the hardening of the majority’s views on non-

Islamic religions. This particular outlook holds that Pakistan is fundamentally

an Islamic nation. Hence, other non-Islamic faiths should have no place in this

religio-political entity. Or, to put it slightly differently, since the raison d’être of

the Pakistani nation is Islam, to speak of or mention other religions in this

exclusive polity is quite simply counterintuitive.

Second, given the predominance of this particularised notion of the identity

of the state, the majority also feels it necessary to distinguish their own place or

identity (symbolic or otherwise) vis-à-vis the rest. Therefore, if Pakistan implies

it is “the land of the pure”, those who do not share its core identity, i.e., Islam,

are “impure”. If we regard ‘the physical body a symbol of society’,45 Christians

(among with other non-Islamic religionists) in that imagination constitute the

community of na-Pak, the impure and the unclean entities (bodies).46

Therefore, the majority-minority divide and consequently the confronta-

tion can be explained within that specific framework of imagination. According

to Todorov, a group confronts the problem of the ‘other’ by classifying it as

equal (similar) or different (inferior). Consequently, that specific group’s iden-

tity is built and rebuilt and strengthened through the contact with the other

who is also different; hence if the other is considered inferior, bad and hated,

the majoritarian group constantly seeks ways to reinforce that stereotype.47

45 See, M. Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo

(Routledge, New York, 2002).

46 In a reductionist analysis of the body and identity, if according to the popular imagina-

tion their (Christian) beliefs are said to make them “impure” and “unclean”, some of the

institutions of the state have gone an extra length to put a stamp of official approval on

such constructions. A case in point is the advertisement of jobs for cleaners in various

municipalities across the country. Most of these institutions routinely advertise that

the municipality “would prefer Christian applicants” for such jobs. See, O. Waraich,

‘In Pakistan, Christianity Earns a Death Sentence’, Time, 4 December 2010, p. 33.

47 An introduction to this can be found in, T. Todorov, On Human Diversity: Nationalism,

Racism, and Exoticism in French Thought (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, ma, 1998)

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

168 Misra

Third, in relating to rules surrounding purity and pollution and impurity

and danger in an ordering of social hierarchy, these unclean, impure bodies are

a visible threat to the mainstream purity. Put simply, the very presence and

existence of an impure Christian is an assault on true and pure Pakistani iden-

tity, metaphorically and otherwise. Given the growing and widespread domi-

nance of notions of pure and impure, there has been a consequential decay in

majoritarian morality in relation to their attitude towards Christians.

For Walzer, the importance of a “thick” view to project what is moral and

just cannot be underestimated. In his view, thick morality is “richly referential,

culturally resonant, locked into locally established symbolic system or network

of meanings”.48 A thin morality, therefore, would constitute a depressingly

counterproductive worldview intent upon building boundaries and seeking

out targets to attack.

It is the abandonment of that thick morality – a morality that celebrated the

diversity of the Pakistani state, its rich heritage, and the common contribution

to the development of this nation – in favour of a thin exclusive imagination

that would seem to sit at the heart of this inter-communal conflict dynamic.

Evaluated in this framework, the intolerance of the radical Muslims in Pakistan

towards their Christian counterparts would constitute consolidation of that

thin morality.

It is worth asking, at this point, how the transformation from a thick to a

thin understanding happened and why? While engaging in this exercise, we

are confronted by the following interrelated questions: Is it simply a case of the

mainstream (Sunni-dominated) society becoming more religiously hard-line?

If so, why? In addition, one also needs to ask if the political agencies contrib-

uted to the thinning of religious tolerance.

3 Logic of Targeting

While it is vital to examine the “thick” and “thin” commitment to religion in

order to interpret and explain communal cooperation and divide there are

also other attendant principles that condition and contribute to such conflict

dynamics.

It is true that all minorities in Pakistan (Ahamadiyas, Hazaras, Hindus, Kalash

Kafirs, Mehdi, Shi’ia Muslims and Sikhs) have experiences of discrimination and

violence at the hands of the majority and before the institutions of the State.

Puzzling, however, in recent years, are the Christians in this narrative of

48 Walzer, supra note 38, p. xi.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 169

conflict, who appear to have attracted much more attention from their radical

Islamic co-citizens than other groups. If anything, attacks on Christians are

consistent, disproportionate and ever increasing. In many ways, contemporary

discourse and activism surrounding inter-communal violence in Pakistan puts

Christians at its very centre. Crudely put, this community seems to have been

marked as a key “target” by radical Muslims, but why so?

In this context, using the Horowitzian framework of conflict generation,

one could argue that the selective targeting of a given community or group

is guided by three inter-related principles. First, if the target group is regarded

as a long-standing (vis-à-vis the majority community) enemy. Second, if it

presents a political threat, and third, if it possesses external connections that

augment its internal strength. In sum, from a majoritarian perspective, if the

given minority is thought to exhibit any of these characterological traits; it is

more likely to be targeted in violence than if it lacks those characteristics.49

How does the Christian minority in Pakistan fit in this framework of expla-

nation? For the sake of greater clarity, it is vital that we explore each of the

above mentioned target identification processes in turn.

The first question concerns the issue of the target group being associated

with a long-standing external enemy. “Complex historical and social factors

have shaped the interaction between religion and politics in Pakistan” and con-

sequently the relationship between the majority and minority communities.50

To some observers, “religious minorities with inferred ties to outside states are

subject to particularly strong pressure as ciphers for actions of those states”.51

For instance, given Pakistan’s traditional enmity with India, the Hindu minor-

ity has always been clothed in that ‘enemy’ category.52 But what about the

Christians?

Interestingly, the logic that considers Hindus as anti-Pakistani is liberally

applied in the construction of a given image of Christians. In a politically charged

social context, the Christians, owing to their religion, are easily equated with

the West and Pakistan’s majority shares an uneasy relationship with the West.

Pakistan views the West in a low light and, therefore, it is that specific outlook

that has come to dominate its views on Christians. Thanks to a shared religion,

the Christians are condemned as “proxies for the West”. It is this overarching

49 D.L. Horowitz, The Deadly Ethnic Riot (University of California Press, Berkeley, ca, 2001)

p. 151.

50 Rais, supra note 6, p. 448.

51 Gregory and Valentine, supra note 8, p. ii.

52 I.H. Malik, Religious Minorities in Pakistan (Minority Rights Group International, London,

2002) p. 26.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

170 Misra

trans-national religious belief which has contributed to the construction of

their “enemy” image. The everyday violence the Christians face is misdirected

anger at the West.53 This is substantiated by some Pakistani scholars. Accor

ding to Akbar S. Ahmed, “while militant groups are frequently the culprits in

attacks on Christians, a general anger against the United States has caused

large numbers of people (read ordinary Muslims) to target Christians, whom

they associate with America, as scapegoats”.54

On the second issue of minorities as a political threat, it can assume a

general currency if the majority is found to be undergoing a crises of confidence.

Select targeting of a given ethnic or religious group during crisis of confidence

among the majority is an established phenomenon.55 If at a given time the

majority community suffers from low morale or feels insecure in the overall

assessment of its identity, then it would vent its anger against its numerically

less powerful co-citizens.56

This particular scapegoating assumes intensity if for some reason the hege-

monic majority associates the minority with an external event, actor or power.

Feeling impotent in the face of external threats or lacking power to confront

this enemy section of the majority may castigate the minority while branding

them traitors, fifth-columnists and even as anti-nationals. In the ensuing

majoritarian activism, the hapless minority attracts all the negative attention

and finds itself in the eye of the storm.

It is the lack of confidence to engage with the external enemy face to face,

which leads to a form of internal implosion. It is during these crises periods

that the regime, institutions of the state and the majority come together to

create an alliance that seeks out easy targets to vent their own sense of

impotency.

It goes without saying that the Pakistani state and its majority community

(Muslims) have consistently nursed an uneasy temperament towards India

53 Kaleem, supra note 18, p. 7.

54 Ahmed, supra note 2, p. 9.

55 For an early and succinct discussion, see, D.L. Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict

(University of California Press, Berkeley, ca, 1984).

56 Several cases abound in contemporary international politics that confirm this particular

position. Serbian attack on the Kosovo Albanians, Saddam Hussein’s continual persecu-

tion of the Shi’ias and Kurds and more recently, radical Islamists attack on Christians in

Pakistan are all cases in point. In all these three cases, the given minority was reduced/

alleviated to an enemy position because the regime or the majority community con-

cerned felt powerless against some external powers. Consequently it tried to bring about

parity or reclaim its superiority by condemning the given minority to various forms of

persecution.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 171

and have felt vulnerable to the West.57 Unsurprisingly, various civilian, as well

as military regimes, the military and the radical Islamists in Pakistan, have

openly engaged in minority bashing in the public arena in order to exorcise

their own private fears and anxieties in relation to external actors.

On the third issue of the targeting owing to the group’s external connections

is slightly problematic in the context of Pakistani Christians. It follows an

established pattern of conferring an enemy status by default during times of

extreme socio-economic and political upheaval.58

Some theorists suggest that when a community feels particularly low and

vulnerable, that given community may engage in spreading “extreme stereo-

typic contents” against the less powerful of the groups to vent its anger against

the external enemy near which it feels impotent.59

Christians’ specific religious identity automatically makes them susceptible

to Islamic extremism that associates the West with Christianity and thus by

default, the Christians of Pakistan have long been recognised as an enemy. As

Bar-Tal and Teichman argue, “the majoritarian belief that there is an enemy in

their midst is related to the definition of a conflict”.60 For example, when the

United States and the coalition forces began their war plan against the Taliban

regime in Afghanistan way back in December of 2001, “Pakistani Christian

leaders demanded security cover for themselves and their Churches”.61

In view of some observers, “many Muslims, not only extremists, believe

that Christians are in collusion with the Western powers and that to attack

them is to attack the West”.62 Hence, unable to confront the enemy directly,

this constituency has from time to time used the minority Christians as a

convenient scapegoat. This position finds ample manifestation in some recent

events.

57 Interesting discussion on this can be found in, S. P. Cohen, The Idea of Pakistan, (Brookings

Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 2004); A. Lieven, Pakistan – A Hard Country (Public

Affairs, New York, 2011).

58 For instance, when there is an attack on a Muslim place of worship in India, it leads to a

simultaneous target of Hindus, Sikhs and Christians in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

59 D. Bar-Tal and Y. Teichman, Stereotypes and Prejudice in Conflict: Representations of Arabs

in Israeli Jewish Society (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005) p. 71.

60 Ibid.

61 bbc News, ‘Analysis: Pakistan’s Christian Minority’, 29 October 2001, <www.news.bbc

.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/1625976.stm>, visited on 12 September 2012.

62 N. Saeed, ‘No Home for Persecuted Pakistani Christians in any State’, Pakistan Christian

Post, 1 May 2014, <www.pakistanchristianpost.com/headlinenewsd.php?hnewsid=3105>

visited on 13 April 2015.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

172 Misra

Following the terrorist bomb blast in All Saints’ Church in Peshawar

in September 2013, which claimed 86 Christian lives, the spokesman of

Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (tte-P) group that claimed responsibility, later

justified its actions by suggesting “until and unless drone strikes are stopped,

we will continue to strike wherever we will find an opportunity against non-

Muslims”.63

The external actions that have had repercussions on the country’s minori-

ties have been long been recognised by this community and have proved pain-

fully prophetic. According to Fr. Javed Akram Gill, a parish priest in the town of

Abbotabad (the site of Osama bin Laden’s killing), “every time the Americans

say or do something, Christians in Pakistan become the number one target”.64

For the sake of brevity of the argument, one only needs to compare the dates

or the time frame between Fr. Javed Akram Gill’s expression of anxiety grip-

ping his community and the claim made by the tte-P.

4 Hate and Scapegoating

These earlier discussed primary conditions are also aided by what one might

regard as secondary or attendant conditions that contribute to “pre-select”

the Christians as legitimate targets. These secondary conditions can be

explained within the contexts of religio-cultural devaluation, negative stereo-

typing, scapegoating and object of hate. For each one of these frameworks of

identification provides critical momentum when selecting a target group and

eventually heaping forms of violence on them. For some theorists, devalua-

tion of individuals and groups, whatever its sources, makes it easier to harm

them.65 It also serves as an avenue to prop up the group initiating this process

to feel superior. As Staub puts it, “diminishing others is a way to elevate the

self”.66

Socio-religious devaluation brought in by strict differentiation between in-

group and out-group, us and them, or kafirs and Muslims involves a cognitive

simplification of values along a continuum. Within this process the dominant

63 Quoted in S. Mohsin, ‘Tackling religious intolerance and violence in Pakistan’, cnn,

24 September 2013, p. 8.

64 J. Khan, ‘Pakistani Christians “number one target” after the death of Bin Laden’, <www

.asianews.it/news-en/Pakistani-Christians-number>, visited on 13 June 2011.

65 A. Bandura, Aggresson: A Social Learning Analysis (Prentice Hall, Chicago, il, 1973).

66 E. Staub, The Psychology of Good and Evil (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003)

p. 299.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 173

group exaggerates the narrative of difference in order to easily generate an

anti-out group sentiment.67

Similarly, if an in-group and out-group distinction exists between the

majority and minority, then the later may find themselves devalued and

made scapegoats if it is found to be in any way related to primary enemies of

the majority. Given their shared history of persecution, there exists a precari-

ous solidarity between Christians and Hindus in Pakistan. As a measure of

safety from the radical targeting many of the country’s Hindus (a) have

converted to Christianity; (b) sought political alliance with them; (c) forged

hybrid forms of Hindu-Christian religious practices and worship beside

Christians, in order to escape the worse consequence of prejudice in contem-

porary Pakistan.68

A mere survival strategy of the hapless minority has incensed radical Sunni

Islamists of the Taliban-variety. Ideally, they would have liked (a) Hindus to

convert to Islam (rather than Christianity); (b) not formed another conten-

tious identity in a strict Islamic state. Consequently, since Christians have been

instrumental in providing shelter and succour to Hindus, they have inadver-

tently assumed the character of the enemy by default. Hence the traditional

antipathy and anger that radical Sunni Muslims have entertained towards

Hindus (largely due to the historical narrative of two-nation theory which cre-

ated India and Pakistan) finds an easy repository in the Christians.

Furthermore, their scapegoating is made easier not only because Christians

belong to the out-group category, but also because they have forfeited their

rights from the moral realm of protection (that Islam traditionally provided to

minorities living within its fold) because of their reaching out to the nation’s

traditional enemies – the Hindus. Since Pakistani nationalism was built on

religion, i.e., Islam vis-à-vis Hinduism, any association with its arch nemesis, i.e.,

Hindus, creates a constituency of intolerance among extremist Islamic nation-

alists in the country. Needless to add, often times it is this association between

Hindus and Christians and an extremist nationalist imagination that has freed

a constituency in Pakistan from any ethical constraints against attacking

the Christians.

67 Horowitz, supra note 49, pp. 43–44. Other intra-Islamic minorities such as Shi’ias and

Ahmadis often bear the brunt of this devaluation in Pakistan. In Karachi, the country’s eco-

nomic capital graffiti targeting Shi’ia and Ahmadi is everywhere, often calling them infidels

and giving pretexts for slaughtering them. For a detailed discussion, see, M.Q. Zaman,

‘Sectarianism in Pakistan: The Radicalisation of Shi’ia and Sunni Identities’, 32:3 Modern

Asian Studies, pp. 689–716.

68 Gregory and Valentine, supra note 8, p. 21.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

174 Misra

While as a rule of thumb, justification typically relates to what is seen as

specifically offensive to the target group, often times it can also extend beyond

those offenses.69 Paradoxical as it may seem, at a subliminal level the radical

Islamist anger and hate towards the Christians could be argued as a product of

deep-seated psychological inadequacy. This inadequacy or complex is guided

by two sets of anxieties. The first relates to the colonial legacy – when British

rule was associated with Christianity and power.70 The second one is a reckon-

ing that Christians occupy an elite identity (English education, a correspond-

ingly different life style, ability to enjoy alcohol, etc.). Very often the secular

Islamic elite of Pakistan get to entertain the trappings of these cultural facets,

which are otherwise not available or denied to the Muslim majority.

Examined up close, one could easily identify the fallacies in the above two

accusations. In the first place, the majority of Christians have had nothing to

do with British colonialism. They mostly came from lower-caste Hindu back-

grounds (who converted to Christianity in the 1800s to escape the caste hierar-

chy and oppression of orthodox Hinduism).71 In addition a great many of

Pakistan’s Christians live in rural areas and urban slums with little or no access

to the elite identity described earlier.

However, such is the intensity of extremist Islamic disaffection towards this

constituency that they hardly bother to take into account the falsities involved

in the traditional stereotypes associated with Christians. Moreover, since no

avenues exist to revolt against the long-gone colonialism and the lack of ability

to confront the country’s power-holding secular elite (who speak English and

favour a liberal lifestyle), the radicals have found it convenient to channel their

collective fury towards the powerless Christians.

Assessed within this framework, one could argue an anxiety-laden percep-

tion that systematically exaggerates the image of the other eventually commits

the group against, which it is projected to the position of an outsider. Having

consigned it to that particular image, the group orchestrating this process

assigns the outsider to a legitimate object of hate. Following on that, in a

complex religio-political context, the initiator of this image construction even-

tually induces the mainstream to hate the subjugated and the marginal.72

Consequently, hate here is not only legitimised, but it is rationalised too.

69 Horowitz, supra note 49, p. 528.

70 J. Cox, Imperial Fault Lines: Christianity and Colonial Power in India, 1818–1940 (Stanford

University Press, Palo Alto, ca, 2002).

71 L. S. Walbridge, The Christians of Pakistan: The Passion of Bishop John Joseph (Routledge

Curzon, London, 2003) pp. 15–16.

72 Bar-Tal and Teichman, supra note 59, p. 73.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 175

Besides, when this hate is acquired through a process of selective reading of

the minority identity, it becomes a powerful psychological collective force

intent upon causing maximum damage.

5 Between a Hammer and an Anvil

The Christian community in Pakistan has never had it easy. Apart from being

subjected to majoritarian hatred and hostility, their lives have also been sub-

jected to State-sanctioned official discrimination and persecution.73 According

to one critic, the record of Pakistan’s judiciary about protection of the rights of

religious minorities is uneven and has witnessed a drastic change – from com-

plete protection of the minorities to their outright condemnation in the

nation’s polity over a sustained period of time.

The first phase (from the time of the nation’s independence in 1947 until

1970), is remarkable for unequivocal protection of freedom of religion and

religious minorities.74 The second phase (during the rule of Zulfikar Ali

Bhutto in the 1970s), contracted this protection through undue deference to

the legislature. In the last phase (from the 1980s until now), the judiciary capit-

ulated before ascendant forces of religious reaction and abdicated its protec-

tive role.75

To sceptics, however, in a country consecrated as a Muslim homeland, such

an eventuality was inevitable. To argue that some aspects of the law designed

to protect minorities and foster inter-communal harmony have been gradually

abandoned and patently abused to place radical Islamists, is not an exaggera-

tion. In view of one critic, when it comes to law, Pakistan’s higher judiciary has

formulated a cavalier approach to the protection of minorities and their rights.

Moreover, they have in fact provided ample scope for radical extremists to

dictate laws that effectively persecute Christians and other minorities simply

73 Waraich, supra note 46, p. 33.

74 See, for instance, the sentiment of the founder of Pakistan M.A. Jinnah on the place of

minorities in the newly created nation. “You are free; free to go to your temples, you are

free to go to your mosques, or to any other place of worship in the State of Pakistan. You

may belong to any religion or caste or creed-that has nothing to do with the business of

the State …We are starting with this fundamental principles that we are all citizens and

equal citizens of our State”. M.A. Jinnah, Jinnah Speeches and Statements, 1947–48

(Introduction by S. M. Burke) (Oxford University Press, Karachi, 2000) p. 17.

75 T. Mahmud, ‘Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial

Practice’, 19:1 Fordham International Law Journal (1995) p. 40.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

176 Misra

because of difference in faith.76 Such hegemonic discrimination and institu-

tional violation of minority rights in an Islamic polity brings into question the

global responsibilities and obligations.

If the international community (read the West) feels passionately about the

lives and liberties of people under persecution by authoritarian and autocratic

regimes, does that entail the scope of intervention on their behalf in an Islamic

state such as Pakistan? Debating such an undertaking, however, requires a

thorough assessment of the conditions on the ground. Before one goes down

the path of actual intervention or even the mere mention of it, it is pertinent to

ask, how does the international community view the minority Christian ques-

tion in Pakistan in the first place?

Despite a history of persecution, Christians in Pakistan have been peaceful

even in the face of extreme provocation.77 The fact that their condition is made

worse because the “Pakistani state is engaged in or have tolerated severe viola-

tions of religious freedom” is even recognised by the U.S. State Department’s

List of Countries of Particular Concern in respect of religious freedom since

2003.78 Other external bodies such as Minority Rights Group International

placed Pakistan in the top ten of its list of states violating minority rights for

both 2007 and 2008.79 More recently, agencies such as Human Rights Watch

and Amnesty International have singled out Pakistan as a cause of serious con-

cern while assessing the anti-Christian violence in the country. Clearly the

condition of minorities in general and Christians in particular in Pakistan is a

grave human security issue. How then was one able to respond to such a chal-

lenge in an era of cosmopolitan responsibility?

In an age of liberal interventionism, the normative course would be to seek

ways of addressing the issue through some form of intervention. Such an

undertaking to intervene (diplomatic, moral or otherwise) on behalf of those

Christian’s facing persecution, however is fraught with complex challenges and

may prove extremely problematic. In recent years Pakistani Christian organisa-

tions have appealed to Washington to restrict U.S. military aid to Pakistan or

exercise diplomatic pressure to protect minorities,80 but to no avail.

76 An interesting overview on this can be found in, M. Lau, The Role of Islam in the Legal

System in Pakistan (Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden, 2006).

77 Rais, supra note 6, p. 461.

78 uscirf, United States Commission on International Religious Freedom – Annual Report

2011 <www.aina.org/reports/uscirf2011.pdf> visited on 17 June 2011.

79 Minority Rights Group International, State of the World’s Minorities 2008 (Minority Rights

Group International, London, 2008).

80 Kaleem, supra note 18, p. 7.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 177

Two interrelated factors in this context dominate the minority plight dis-

course and foreclose any possible roll back of aid or any form of diplomatic

intervention or otherwise on behalf of the hapless Christians. First, there is a

moral deficit on part of the West (read the United States) to go down that path

lest that would alienate Pakistani authorities in its partnership with the West

against the “war on terror”.81 This fear of alienation is so pervasive that the

West has shied away from entertaining even the liberal argument that “human

rights must be an essential part of dialogue and discussion” when it comes to

providing overseas aid to countries such as Pakistan.

Second, any generic discussion leading to an eventual policy position is

fraught with the very complex attitude that Islam, in general, and Muslim

people, in particular, hold towards external intervention. As one Christian

cleric of Pakistani origin has put it, “their (Muslims) complaint often boils

down to the position that it is always right to intervene when Muslims are

victims… and always wrong when Muslims are oppressors or terrorists”.82

Unsurprisingly the West’s refusal to engage with the issue has led some

Christian leaders in Pakistan to argue that their plight is not heard outside

Pakistan and the international community has abandoned them. Speaking in

the aftermath of attack on the All Saints’ church in Peshawar in 2013 (consid-

ered worst-ever attack against Christians in the country’s history), Mano

Rumalshah, the bishop emeritus of Peshawar, stated, “everyone is ignoring the

growing danger to Christians in Muslim-majority countries. The European

countries don’t give a damn about us”.83

On balance, given the problematic and volatile nature of this discourse and

potential threat to an already embattled relationship between Pakistan and

the West, such an undertaking is unlikely.84 Put simply, under the circum-

stances, the solution to the protection of Christians in Pakistan should come

from within – not from outside. If that is so, do we have a constituency that can

commit itself to such an undertaking?

81 Gregory and Valentine, supra note 8, p. 3.

82 bbc News, ‘Bishop Attacks ‘Muslim hypocrisy”, 5 November 2006, <www.news.bbc.co.uk/1/

hi/uk/6117912.stm>, visited on 08 June 2011.

83 J. Boone, ‘Pakistan church bomb: Christians mourn 85 killed in Peshawar suicide attack’,

The Guardian, 24 September 2013, p. 7.

84 Note, for instance, the opposition of some religious leaders in the West against providing

aid to Pakistan unless Islamabad commits to any religious freedom for Christians and the

British Foreign and Commonwealth Office (fco) refusal to entertain such demands. bbc

News, ‘Cardinal brands uk aid foreign policy “anti-Christian’’’, 11 March 2011, <www.bbc.co

.uk/news/uk-scotland-12738479>, visited on 7 July 2011.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

178 Misra

Oftentimes, societies undergoing such radical change create mass con-

sciousness against extremism in the form of positive civil society initiatives.

Unfortunately, the civil society in Pakistan in the current atmosphere of

religio-political turmoil is in the retreat – and increasingly exhibiting signs

of terminal powerlessness and decline. Thus the likelihood of an endogenous

actor or group of actors making a positive change for Christians appears

unlikely.

6 Assessment

Religious minorities, in general, and Christians, in particular, are a persecuted

lot in Pakistan. They are “woefully small and politically powerless”.85 Owing

to their specific faith, the Christians of Pakistan are discriminated against, per-

secuted and killed. One could argue in the current atmosphere that Christians

in Pakistan are undergoing an organised and premeditated majority-sponsored

process of devaluation. “We are like Jews in medieval Europe,” commented one

of the interviewees in this study, while recounting the travails and traumas of

his community.

Such individual security concerns have a collective resonance as well.

According to one recent study, like every other minority in the state of

Pakistan, the Christians are absolutely helpless to do anything about their

circumstances.86

The security vacuum in which Christians find themselves is an ever-

widening one. Although they appear homogenous from an external perspective,

their condition is further complicated by the fact that unlike their Muslim

counterparts, Christians do not possess any tribal or group network that could

provide a modicum of security at a time when the state has either abandoned

its law and order obligations and/or is in the retreat. Consequently, while

Christians are made targets for their faith by the extremist Sunni Muslims,

other opportunists feed on them for whatever wealth they have or for their

women.

In the absence of a clearly defined state-sponsored security umbrella for

their protection, they constitute easy targets. At an individual level, Christians

live in a bracketed existence. According to some observers, “It’s easy for kid-

nappers to abduct a minority member compared to local people. Minorities

85 Raina, supra note 1, p. 15.

86 Gregory and Valentine, supra note 8, p. 39.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 179

don’t have tribal support, and don’t have the security guards and weapons

that locals do”.87 In the past this community would have received some

degrees of protection from its immediate Muslim neighbours. However,

growing militancy and the tendency to brand anyone sympathising with

minorities as an anti-Islamic activity has precluded any such societal security

guarantees.

How does a minority group cope with the everyday likelihood of kidnap,

forced conversion, rape or death at the hands of its majority co-citizens?

The immediate instinctual response for a minority group facing such degrees

of persecution often results in two sets of out-migration. In the first instance,

it seeks ways to abandon its place of birth and migrate to a third country.88

Faced with such security challenges, various minorities in Pakistan (Hindus

for instance) have sought refuge in India in ever-larger numbers in recent

years.

Such an option, however, is not available to the country’s Christians.89 There

are simply very few states that speak out against the persecution of Pakistan’s

Christians or provide safe haven when the later seek refuge and asylum in a

third country. This is an ironic double bind situation for a community whose

identity is forcefully linked outside Pakistan and they are condemned because

of this association.

Secondly, in the absence of a critical protecting voice from outside and feel-

ing the pressure from inside, the community is slowly giving in to the majori-

tarian persecution. There is a slow, but steady out-migration of Christians in

Pakistan; not physical, but religious. Throughout the country reports abound

of entire Christian families and even villages embracing Islam in order to

escape the institutional ostracism, apathy of the state to their plights, and

overall militancy of extremist Islamists.

87 N.P. Walsh, Pakistan Kidnappings Highlight Dangers for Religious Minorities, 18 March,

2011, www.religion.blogs.cnn.com/2011/03/18/pakistan-kidnappings-highlight-dangers-for

-religious-minorities/, visited on 20 June 2011.

88 For another contemporary story of Christian migration following persecution see,

Y. El Rashide, ‘Egypt: The Victorious Islamists’, 58:12 The New York Review of Books (2011)

pp. 17–19.

89 A snapshot of this sentiment of abandonment can be summed up in the statement below:

In March 2011, Asiya Nasir, a Christian lawyer told the Pakistani parliament: “Today

I want to address Muhammad Ali Jinnah (the father of the nation). You told us to come

here and make a home with you. When the Gojra tragedy happened, I said that our

future generations will ask us if we regret coming here. Now, we are filled with regret”.

See, O. Waraich, ‘Pakistan’s Christians Mourn, and Fear for their Future’, Time, 8 March

2011, p. 39.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

180 Misra

7 Conclusion

Pakistan’s religious minorities share a widespread sense of discrimination and

face constant majoritarian Sunni Islam-led persecution.90 Christians who

remain a tiny and politically weak community feel the heat of persecution

more compared to their other minority counterparts. The rising tide of indi-

vidually mediated charges of blasphemy, as well as organised majoritarian

vigilante violence against this community is a product of both the erosion of

thick religiosity among the masses and the consolidation of institutional

religious orthodoxy.

The radical orthodox view of minorities as a “threat” to the Pakistani nation

has coalesced in the last decade due to several external factors. The negative

stereotyping and select targeting of Christians is to some extent a by-product

of Pakistan’s uneasy relations with the West, India and the overall external con-

ditions. Since the Pakistani society at large finds itself powerless against the

external forces whose actions have a direct bearing on its internal affairs – it’s

anger has turned inward.

A shaky majoritarian self-esteem and recognition of its weakness in the

face of external factors/actors has contributed towards the consolidation of

a watertight vision of ‘us’ and ‘them’. Consequently a section of the popu-

lace does not hesitate to engage in majoritarian hegemonic politics and even

feels it is legitimate to persecute the minorities in general and Christians in

particular.

Furthermore, an underlying sense of majoritarian vulnerability to minority-

led sectarianism (Shi’ia extremism or ethno-nationalism of the Baloch-variety)

has exposed the state and its institutions to perpetual manipulation by a

radical majority. Sufficient to say, “Pakistan’s majority, while variously differen-

tiated and in conflict along ethnic, linguistic and regional fault-lines, has

achieved consensus about the Islamisation of the public spheres”.91

Thanks to this majoritarian sentiment, the country’s judiciary has been fre-

quently subverted and misused by successive regimes (democratic and author-

itarian) as well as individuals in order to establish a Sunni dominated state at

the expense of minorities.92 Unsurprisingly, given this collusion and a long

history of institutional complicity in promoting radical extremism that seeks

90 True, in recent years, their hegemonic Sunni partners have killed more Shi’ia Muslims

than the Christians.

91 Raina, supra note 1, p. 15.

92 H. Haqqani, ‘The Role of Islam in Pakistan’s Future’, 28:1 The Washington Quarterly (2004)

p. 96.

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Life in Brackets 181

to discriminate against minorities, we do not have any mechanism to protect

the persecuted Christians.

The only possibility of rolling back the majoritarian anti-minority sentiment

and its corrosive effect on Pakistani society is perhaps possible under enlightened

leadership and a robust civil society.93 The pervasiveness of vendetta-seeking

majoritarian radicalism, however, has foreclosed any such move in that direc-

tion. In fact, those very few political leaders who have shown courage to stand

up against such partisan politics have themselves become victims of extremist

designs.94

This leaves us with the prospect of some form of external intervention on

behalf of Pakistan’s hapless Christians. Unfortunately, however, due to com-

plex and volatile relationship that the West and Pakistan share, any such move

on that front is highly unlikely. In light of such dire realities, the Christians of

the country seem condemned to a long drawn out majoritarian persecution.

93 For an interesting argument along these lines, see, P. Hoodbhoy, ‘Pakistan’s Westward

Drift’, Himal, September 2008, pp. 11–13.

94 Note, for instance, the brutal assassination of Shahbaz Bhatti, Pakistan’s Minorities

Minister in March 2011 – this occurred shortly after the slaying of Punjab governor

Salmaan Taseer (by his own bodyguard) in January of the same year (both the slain leaders

had called for the blasphemy law to be lifted).

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 157-181

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Causes of Female Backwardness in Pakistan and An Appraisal of The Contribution That Women Can Make To The Effort of NationDocument27 pagesThe Causes of Female Backwardness in Pakistan and An Appraisal of The Contribution That Women Can Make To The Effort of NationMuhammad Umer63% (8)

- List of Pec Contractors WebsiteDocument92 pagesList of Pec Contractors WebsiteUmair Yahya91% (11)

- Western Political ThoughtDocument570 pagesWestern Political ThoughtMeti Mallikarjun75% (4)

- Pakistan's Tea Culture and Marketing AnalysisDocument49 pagesPakistan's Tea Culture and Marketing AnalysisHumaRiaz100% (1)

- Causes of East Pakistan's SeparationDocument4 pagesCauses of East Pakistan's Separationsyeduop3510Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of The Military in Turkish Poli PDFDocument20 pagesThe Role of The Military in Turkish Poli PDFusman93pk100% (1)

- Positivist Approaches To International RelationsDocument6 pagesPositivist Approaches To International RelationsShiraz MushtaqPas encore d'évaluation

- Positivist Approaches To International RelationsDocument6 pagesPositivist Approaches To International RelationsShiraz MushtaqPas encore d'évaluation

- J. S. Asian Stud. 10 (01) 2022. XX-XX - 3830Document8 pagesJ. S. Asian Stud. 10 (01) 2022. XX-XX - 3830syeduop3510Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gallarotti 2015Document39 pagesGallarotti 2015syeduop3510Pas encore d'évaluation

- Grosfoguel, Ramon 2012. The Multiple Faces of IslamophobiaDocument25 pagesGrosfoguel, Ramon 2012. The Multiple Faces of IslamophobiaBosanski KongresPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Theoretical Framework: 2.1 OverviewDocument11 pages2 Theoretical Framework: 2.1 Overviewsyeduop3510Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ocean and Coastal Management: Yen-Chiang Chang, PH.D Professor of International LawDocument9 pagesOcean and Coastal Management: Yen-Chiang Chang, PH.D Professor of International Lawsyeduop3510Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan Challenges To Democracy and Governence-1 PDFDocument7 pagesPakistan Challenges To Democracy and Governence-1 PDFsyeduop3510Pas encore d'évaluation