Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

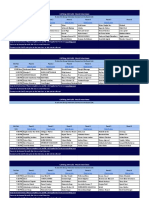

Ds C C Aptitude Unix Rdbms SQL CN Os

Transféré par

Venkatesh YelnoorkarTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ds C C Aptitude Unix Rdbms SQL CN Os

Transféré par

Venkatesh YelnoorkarDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Introduction

Formal Name: Japan

Japan is an island country located in the western Pacific Ocean. Total land area is about 378,000

square kilometers. More than 70 percent of land surface is mountainous. As it is situated along the

circum-Pacific volcanic belt, Japan has several volcanic regions and frequently affected by

earthquakes and Tsunami. A major feature of Japan’s climate is the clear-cut temperature changes

between the four seasons. In spite of its rather small area, the climate differs in regions from a

subarctic climate to a subtropical climate. The side of the country which faces the Sea of Japan has

a climate with much snow in winter by seasonal winds from the Siberia. Most of the areas have

damp rainy season from May to July by the seasonal winds from the Pacific Ocean. From July to

September, Japan frequently suffers from Typhoon.

The capital is Tokyo. Total population is about 127.77 million.

Overview of disasters:

Japan is affected by Typhoon mostly every year and Volcanic disasters triggered by eruption and

volcanic earthquake. Japan is earthquake prone area due to the geological formation with plate

boundaries of the Pacific plate, the Philippine Sea plate, the Eurasian plate, and the North American

plate.

History of disaster management in ancient japan:

Earthquakes Absent From Japanese Classics

The Japanese archipelago is located in a zone of high seismic activity, and there are numerous

records of earthquakes over the country's history. In classical Japanese literature, however,

earthquakes are almost entirely absent. Why is this? There are two main reasons.

First, earthquakes are primarily urban disasters. Most earthquake victims are city dwellers who are

killed either by fires or by rubble from falling buildings. But large cities with tall buildings are a

relatively recent phenomenon. In ancient and medieval Japan, even towns were relatively rare, and

these were really little more than overgrown villages. The only tall buildings were Buddhist

pagodas.

In addition, the traditional Japanese house took into account the threat of earthquakes. The frame

was made of wood and held together by interlocking joints, rather than nails. The interior “walls”

(fusuma) were made from paper. The main pillars were not driven into the ground or fixed to the

foundations. Instead, they rested on rounded stones. This looser connection allowed them to remain

relatively stable even if the ground shook violently underneath.

A view of Mount Fuji and the extinct volcano Mount Ashitaka from Famous Places of the Fifty-

Three Stations by Utagawa Hiroshige.

The second reason that we have so little information about historical earthquakes from

contemporary sources is purely ideological. In the political philosophy of Japan (and other parts of

East Asia), an earthquake was seen as punishment from heaven for poor or unjust government. For

this reason, anyone who dared to write about or depict an image of an earthquake would be

regarded as a critic of the powers that be.

The reluctance to represent natural disasters extended to volcanic eruptions as well as earthquakes.

Mount Fuji is now a symbol of Japan and its natural beauty, but this was not always the case. While

the people of the Edo period (1603–1868) regarded it with awe as a sacred place, they feared its

volcanic temperament. Fuji last erupted in 1707, after a series of minor tremors that followed a

large earthquake some weeks earlier, showering the whole of Edo (now Tokyo) with a layer of ash.

But there are almost no written records of this great disaster. Artists continued to paint a majestic

and tranquil Mount Fuji, as if the eruption had never happened. Poets took the same approach.

Modern japanese disaster mangement programme:

Developing Role-specific Disaster Management Plans by a

Three-tiered Administration Consisting of the National,

Prefectural, and Municipal Governments

In the Japanese Disaster Management System, a Minister of State for Disaster Management is

appointed to the Cabinet, and the Disaster Management Bureau plans the basic policy on disaster

management and plans and makes overall coordination on response to large-scale disasters. In

normal times, Ministers of State, representatives of relevant organizations and experts form the

Central Disaster Management Council in the Cabinet Office to discuss important matters such as the

development of national disaster management plans and basic policies and to take charge of

promoting comprehensive disaster countermeasures by indicating a major policy.

Japan is governed by a three-tiered administration: the national government, prefectures, and

municipalities. The head of each level takes full responsibility for that jurisdiction in a structure

similar to that of a nation. Comprehensive disaster prevention plans are developed in accordance

with the roles to be performed at each stage.

In the event of a disaster, or where there is a risk of a disaster, the Cabinet Office, with the

cooperation of relevant ministries and agencies, takes the lead in countermeasures, corresponding to

each level of disaster with level 1 at normal times up to level 5 when a devastating disaster occurs

(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

When a large-scale disaster occurs, an Emergency Response Team made up of director-general class

members of related ministries and agencies is summoned to the Prime Minister’s Office to begin

talks within 30 minutes of the occurrence of the disaster. Then an extraordinary cabinet meeting is

held and the Extreme Disaster Management Headquarters is established. The Headquarters, headed

by the Prime Minister as the Chief, makes the policies and provides overall coordination regarding

disaster emergency measures. Accurate and prompt actions are expected to be taken in response to

the instructions from the Chief.

Go to:

The Emergency Measures Activity Plan Goes into Action

Immediately without Waiting for Assistance Request

Prompt and accurate emergency response is demanded in the event of a disaster, and to ensure its

reliability, the government may establish the Onsite Headquarters for Disaster Management. For

example, during the Hiroshima landslides in August 2014, the Onsite Disaster Management

Headquarters was set up and headed by a State Minister of Cabinet Office. Likewise, Prefectural

Disaster Management Headquarters and Municipal Disaster Management Headquarters are set up in

affected areas and these administrative units coordinate operations.

Next I would like to introduce an overview of the specific plan. Fig. 2 shows an outline of current

measures considered by the Central Disaster Management Council in response to large-scale

earthquakes. It specifically suggests that the possibility of a Nankai Trough Earthquake (with a

magnitude of 8 or 9) and a Tokyo Inland Earthquake within the next 30 years is greater than 70%.

The council is presently reviewing the estimation of damage based on the Great East Japan

Earthquake while promoting countermeasures.

Fig. 2

After reviewing the damage estimation, it was assumed that a tsunami generated by the Nankai

Trough Earthquake and fires that broke out in the Tokyo Inland Earthquake would cause a high

proportion of deaths. In particular, a tsunami from the Nankai Trough Earthquake is expected to

affect massive areas, causing enormous damage.

In March 2015, based on the estimation of these damages, the specific Emergency Management

Plan for a Nankai Trough Earthquake was newly established (Fig. 3). This plan is made up of five

categories in response to large-scale disasters: emergency transportation routes; rescue, first aid, fire

fighting, etc.; medical; supplies; and fuel.

Fig. 3

By incorporating lessons learned in the Great East Japan Earthquake, its main feature is that the

Extreme Disaster Management Headquarters will grasp a whole picture of the damage and action

can be taken immediately without waiting for receiving requests for assistance from the affected

areas. Wide-area support units such as the police, firefighter and Self-Defense Forces are planned to

be dispatched with a concentration on key support accepting prefectures where great damages are

expected.

For life saving, a timeline with target activities is set up for the five afore-mentioned categories

while keeping in mind the initial 72-hour maximum period for rescue, coordinating each activity

according to the elapsed time from when the disaster struck.

Regarding medical care, JMATs (Japan Medical Association Teams) and DMATs (Disaster Medical

Assistance Teams) are dispatched over a broad area during the initial 72 hours and requested to

provide assistance to the disaster base hospitals in the affected areas. In addition, the plan is to

quickly build a backup system for treatment by transporting critical patients out of the disaster areas

from air transport centers.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Model Question Paper MSC Entrance ExamDocument1 pageModel Question Paper MSC Entrance ExamVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Warm UpDocument1 pageWarm UpVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Clustering Research Papers: A Qualitative Study of Concatenated Power Means Sentence Embeddings Over Centroid Sentence EmbeddingsDocument13 pagesClustering Research Papers: A Qualitative Study of Concatenated Power Means Sentence Embeddings Over Centroid Sentence EmbeddingsVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Type I & Type II Errors: Incorrectly RejectDocument8 pagesType I & Type II Errors: Incorrectly RejectVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Acknowledgement Receipt 202102104Document1 pageAcknowledgement Receipt 202102104Venkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Road To FMS 2021Document42 pagesRoad To FMS 2021Venkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Saga Panel Price List Signed 290721 SignedDocument1 pageSaga Panel Price List Signed 290721 SignedVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Features of Nosql: Non-RelationalDocument7 pagesFeatures of Nosql: Non-RelationalVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- CATKing Mock Interviews of IIM L, C, CAP, Ahmedabad Call GettersDocument14 pagesCATKing Mock Interviews of IIM L, C, CAP, Ahmedabad Call GettersVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Homemade Food at Your Fingertips: A Rapchick VentureDocument63 pagesHomemade Food at Your Fingertips: A Rapchick VentureVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Current Affairs Reads 19-01-2022Document1 pageCurrent Affairs Reads 19-01-2022Venkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Tdil Mal TagsDocument76 pagesTdil Mal TagsSijo ThomasPas encore d'évaluation

- Stage 1Document29 pagesStage 1Venkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Ty Btech syllabusIT Revision 2015 19 14june17 - withHSMC - 1 PDFDocument85 pagesTy Btech syllabusIT Revision 2015 19 14june17 - withHSMC - 1 PDFMusadiqPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- DFDDocument4 pagesDFDVenkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The MIPS Instruction-Set Architecture: © 2002 Edward F. Gehringer ECE 463/521 Lecture Notes, Fall 2002 1Document8 pagesThe MIPS Instruction-Set Architecture: © 2002 Edward F. Gehringer ECE 463/521 Lecture Notes, Fall 2002 1Venkatesh YelnoorkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Technical Aptitude QuestionsDocument151 pagesTechnical Aptitude QuestionsGodwin SvcePas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Technical Aptitude QuestionsDocument151 pagesTechnical Aptitude QuestionsGodwin SvcePas encore d'évaluation

- Explanation TextDocument4 pagesExplanation TextAndrePas encore d'évaluation

- Disaster Management CompressedDocument266 pagesDisaster Management CompressedIshaan SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Kumpulan Formatif Modul 5Document38 pagesKumpulan Formatif Modul 5Ely IrmawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Example NarrativeDocument10 pagesExample NarrativeMuhammad Chandra FahriPas encore d'évaluation

- Urban Evacuation Tsunamis: Guidelines For Urban Design: Leonel Ramos SantibáñezDocument16 pagesUrban Evacuation Tsunamis: Guidelines For Urban Design: Leonel Ramos SantibáñezElizabeth ArroyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng 25Document14 pagesEng 25csdsesastaPas encore d'évaluation

- Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionDocument2 pagesDisaster Readiness and Risk ReductionJune MarkPas encore d'évaluation

- SuperCorp by Rosabeth Moss Kanter - ExcerptDocument38 pagesSuperCorp by Rosabeth Moss Kanter - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group67% (3)

- English Year 6 PenulisanDocument9 pagesEnglish Year 6 Penulisanieza haryaniePas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Sent Frag Cont.Document2 pagesSent Frag Cont.Unfound TakuPas encore d'évaluation

- Earthquakes and FaultsDocument16 pagesEarthquakes and FaultsJoeseph CoPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 9 (2022) (CO BAN)Document6 pagesUnit 9 (2022) (CO BAN)nguyendongnghi49Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tsunami Visualization WorkflowDocument2 pagesTsunami Visualization WorkflowalexinorbitPas encore d'évaluation

- 4.5 - Earthquake HazardsDocument26 pages4.5 - Earthquake HazardsJboy MnlPas encore d'évaluation

- FOCGB3 Utest VG 5A PDFDocument1 pageFOCGB3 Utest VG 5A PDFMaria BilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hydroelastic Analysis of Pontoon-Type VLFS: A Literature SurveyDocument12 pagesHydroelastic Analysis of Pontoon-Type VLFS: A Literature SurveyFarah Mehnaz HossainPas encore d'évaluation

- OverviewDocument19 pagesOverviewVikram DalalPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL - English 5 - Q1 - W5Document5 pagesDLL - English 5 - Q1 - W5Demi DionPas encore d'évaluation

- Disaster Managment MCQ-2-36Document35 pagesDisaster Managment MCQ-2-36jothilakshmi100% (2)

- Science 10 Quarter 1 Lesson 4Document2 pagesScience 10 Quarter 1 Lesson 4ViaPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- (Skills Lab) : BSN 4A - Group IvDocument14 pages(Skills Lab) : BSN 4A - Group IvSarmiento, Jovenal B.Pas encore d'évaluation

- ASTM E2026-07 - Seismic Risk Assessment of BuildingsDocument17 pagesASTM E2026-07 - Seismic Risk Assessment of BuildingsLJD211Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hydrological Hazards - 3Document31 pagesHydrological Hazards - 3Darbie Kaye DarPas encore d'évaluation

- Report TextDocument8 pagesReport TextjumanaPas encore d'évaluation

- PAPER 1 f4 2021Document13 pagesPAPER 1 f4 2021kaiqianPas encore d'évaluation

- TstructureDocument5 pagesTstructureSweetaddy castilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Natural DisastersDocument6 pagesNatural DisastersΕιρήνη ΑνδρεασίδουPas encore d'évaluation

- Radar Altimetry TutorialDocument307 pagesRadar Altimetry TutorialMatthew Sibanda100% (1)

- Part B. Module 5. Tsunami and Disaster Prevention and MitigationDocument133 pagesPart B. Module 5. Tsunami and Disaster Prevention and MitigationRuel DogmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Morning Workfor 4 TH Grade Free Week Printand Digital Morning WorkDocument17 pagesMorning Workfor 4 TH Grade Free Week Printand Digital Morning WorkAlexPas encore d'évaluation

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearD'EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (23)

- Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessD'EverandAlex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessPas encore d'évaluation