Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Moral Disapproval and Perceived Addiction To Internet Pornography A Longitudinal Examination

Transféré par

timsmith1081574Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Moral Disapproval and Perceived Addiction To Internet Pornography A Longitudinal Examination

Transféré par

timsmith1081574Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Moral Disapproval and Perceived Addiction to Internet Pornography: A Longitudinal

Examination

RUNNING HEAD: Moral Disapproval and Perceived Addiction

Joshua B. Grubbsa

Joshua A. Wiltb

Julie J. Exlineb

Kenneth I. Pargamenta

Shane W. Krausc

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION: None. The authors declare no conflict of

interest.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Joshua B. Grubbs, Ph.D.,

Department of Psychology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, 43403.

Email: GrubbsJ@BGSU.edu

a

Department of Psychology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio, 43403

b

Psychological Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, 44106

c

VISN 1 MIRECC, Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital, Bedford,

Massachusetts

This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not

been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may

lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as

doi: 10.1111/add.14007

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

ABSTRACT

Background and Aims

Internet pornography use is an increasingly common, yet controversial, behavior. Whereas

mental health communities are divided about potentially problematic use patterns, many

laypeople identify as feeling dysregulated or compulsive in their use. Prior work has labeled

this tendency perceived addiction to internet pornography (PA). This study's aims were to 1)

assess the association between PA at baseline and other factors, including actual levels of

average daily pornography use and personality factors and 2) assess the associations between

baseline variables and PA one year later.

Design

Two large-scale community samples were assessed using online survey methods, with

subsets of each sample being recruited for follow up surveys one year later.

Setting

USA

Participants

Participants were adults who had used pornography within the past 6 months recruited in two

samples Sample 1 (N = 1,507) involved undergraduate students from three US universities

and Sample 2 (N =782) involved web-using adults. Sub-sets of each sample (Sample 1, N =

146; Sample 2, N = 211) were surveyed again one year later.

Measurements

At baseline, we assessed average daily pornography use, PA, and relevant predictors (e.g.,

trait neuroticism, trait self-control, trait entitlement, religiousness, moral disapproval of

pornography use). One year later, we assessed PA.

Findings

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Cross-sectionally, PA was strongly correlated with moral disapproval of pornography use

(Sample 1, Pearson’s correlation: r = .68, [.65, .70]; Sample 2, r = .58 [.53, .63]). Baseline

moral disapproval (Sample 1, r = .46, [.33, .56]; Sample 2, r = .61, [.51, .69]) and perceived

addiction demonstrated relationships with perceived addiction one year later. We found

inconclusive evidence of a substantial or significant association between pornography use

and perceived addiction over time (Sample 1, r = .13, [-.02, .28]; Sample 2, r = .11 [-.04,

.25]).

Conclusions

Perceived addiction to internet pornography appears to be strongly related to moral scruples

around pornography use, both concurrently and over time, rather than with amount of daily

pornography use itself.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Moral Disapproval and Perceived Addiction to Internet Pornography:

A Longitudinal Examination

Over recent years, problematic internet pornography use has garnered a great deal of

both empirical1-2 and popular3-5 attention. However, the scientific community is divided in its

considerations of whether problematic pornography use qualifies as an addiction.6-11

Nonetheless, the notion of such an addiction persists in public consciousness, with many

people willing to self-diagnose such a problem.6, 12 Clearly, this contrast between public and

professional opinions represents an important discrepancy between people’s perceived

experiences and the status of scientific literature.

To address this discrepancy, recent research has examined perceived addiction (PA)

to internet pornography,13-14 which refers to a person’s propensity to report feeling

dysregulated and compulsive in their use of pornography. Rather than addressing the

accuracy of the pornography addiction self-diagnosis, PA focuses on the degree to which a

person is reporting a subjective experience of dysregulation. Specifically, the focus is on the

perception, rather than the objectively measured behaviors (e.g., failed attempts to

quit/moderate behavior,15 etc.). Despite this focus on perception rather than pathological

behavior, a burgeoning body of evidence suggests that PA to internet pornography is a

relevant clinical construct.

PA is associated with psychological well-being,16 excessive gaming,17 alcohol use,18

profound distress related to pornography use,14 psychological distress more generally,19

difficulties in religious and spiritual functioning,20 and relational anxieties.21 Longitudinally,

PA uniquely predicts psychological distress, above and beyond baseline levels of distress.16

PA also predicts difficulties in religious and spiritual functioning over time, even when

accounting for baseline levels of such problems.22 Such findings highlight the potential costs

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

of PA and demonstrate the need to better understand this construct, particularly those factors

that might lead to its development or expression.

Cross-sectionally pornography use (as an average of hours-per-day) is positively

associated with PA, suggesting that PA is, at least in part, indicative of some real-life

behaviors. Even so, average daily use accounts for little variance in predicting PA, 13, 23

suggesting that other individual difference variables may be driving PA. Higher levels of

neuroticism seem to be related to PA,24 as do lower levels of self-control.23 Finally,

religiousness and moral disapproval of pornography use (e.g., believing pornography use is a

violation of conscience) relate to PA, moreso than pornography use itself,23 with religious

individuals consistently reporting greater levels of PA to internet pornography, 25 and with

factors such as familial religious history linked to greater experiences of PA.26 Yet—to

date—there have been no systematic examinations of what factors might contribute to

feelings of PA over time. The present study was designed to address this gap in the research.

The Present Study

The purposes of the present study were 1) to assess the association between PA at

baseline and other factors, including actual pornography use and personality factors, and 2) to

assess the associations between baseline variables and PA one year later. Given the known,

concurrent associations of individual difference variables and PA, we considered the roles of

personality factors in predicting absolute levels of PA over time (one year). We examined

trait self-control, a known predictor of both pornography use and PA,12 and neuroticism,

which has also been linked to PA.24 We also examined psychological entitlement, which is

associated with behavioral regulation problems,27 sexual behavior more broadly,28 and

pornography use specifically.29

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

We also assessed religiousness and moral disapproval of pornography, given the links

between those constructs and PA in prior literature.23 We tested average daily use of

pornography (in hours), as pornography use itself is a known associate of PA.13, 23

We expected that, concurrently, we would find links consistent with prior literature,

demonstrating that religiousness, moral disapproval, pornography use, and neuroticism would

all be positively related to PA, and that trait self-control would be negatively related to PA.

We also expected to find that psychological entitlement would be positively associated with

reported levels of average daily pornography use and intensity of efforts to access

pornography, but not related to distress regarding use or perceptions of addiction.

Longitudinally, we hypothesized to find that moral disapproval and actual time spent using

pornography would uniquely predict variance in absolute levels of PA, even when baseline

levels of PA were held constant. We examined these hypotheses in two one-year, longitudinal

studies.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Sample 1. Participants were college students at three universities (N = 3,988; 35.2%

men) in the U.S., a mid-sized private University in the Midwest, a large public university in

the Midwest, and a mid-sized private university in the Southwest. Data were collected over 8

semesters, targeting students in their first two years of college. At baseline, participants were

restricted to those who endorsed viewing pornography at some point within the past 6 months

(N = 1,507, Mage = 19.3, SD = 2.2; 65.2% men, 34.5% women, 0.3% other). Predominant

sexual orientations reported were heterosexual (90.1%), bisexual (4.4%), lesbian/gay (3.3%),

asexual (0.3%), and “other” or “prefer not to say” (1.7%).

At baseline, the most common racial/ethnic identities reported were white/Caucasian

(69.2%), followed by African American (10.6%), Latino/a (6.1%), Asian/Pacific-Islander

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

(16.8%), American Indian or Alaska Native (1.9%), Middle Eastern (1.4%), and “other” or

“prefer not to say” (2.2%). As participants could select multiple racial affiliations, these

percentages exceeded 100%. The most common religious affiliations reported were Christian

(66.0%), followed by Atheist/Agnostic (12.3%), “none” (6.9%), “other” (3.4%), Jewish

(1.4%), Buddhist (0.7%), Muslim (0.5%), and Hindu (0.8%).

One year after the initial survey, participants who were in their first year of college at

the initial survey, who consented to be contacted again, and who had used pornography

within six months of baseline (final N = 623) were contacted for a follow-up survey. Of the

623 contacted, 265 (55.1% men; 42.5% response rate; Mean Interval= 333.2 days, SD= 25.3)

completed the second survey. Of this 265, 146 endorsed having viewed pornography within

six months prior to the second survey (67.2% men; 55% response rate) and were thus

included in analyses.

Sample 2. Participants were internet-using adults in the United States recruited using

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workforce database (Total N = 1,047, 39.6% men).

MTurk is reliable, suitable for psychosocial research, suitable for studying clinical or

psychopathological issues, and comparable to various other community sampling methods.30-

32

Participants were restricted to those who had viewed pornography within the past 6 months

(N = 782, Mage = 32.6, SD = 10.3, 48.8% men, 50.6% women, 0.6% other). Sexual

orientations reported were predominantly heterosexual (83.9%), followed by bisexual (9.3%),

gay or lesbian (3.5%), pansexual (1.5%), asexual (0.5%), and other/prefer-not-to-say (1.2%).

At baseline, the most common racial/ethnic identities reported were white/Caucasian

(79.3%), followed by African American (10.8%), Latino/a (7.1%), Asian/Pacific-Islander

(6.3%), American Indian or Alaska Native (3.8%), and “other” or “prefer not to say” (1.1%).

As participants were able to report more than one ethnic/racial identity, sums may exceed

100%.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

The most common religious affiliations reported were Christian (39.7%), followed by

Atheist/Agnostic (36.4%), “none” (15.8%), “other” (3.4%), Jewish (1.9%), Buddhist (1.5%),

Muslim (0.6%), and Hindu (0.4%).

One year after the initial survey, participants who had completed pornography related

measures at time one and who had also agreed to be notified of future studies (N = 672) were

contacted again and offered the opportunity to participate in a follow-up study. Of the 672

contacted, 366 (52% men; 54% response rate; Mean Interval= 363.3 days, Standard

Deviation= 5.0) completed the second survey. Of this 366, 211 endorsed having viewed

pornography within six months prior to the second survey (73.5% men).

Measures

Perceived Addiction to internet pornography. The Cyber-Pornography Use

Inventory-9 was used.12 This 9-item measure assesses indicators of PA using three subscales:

Perceived Compulsivity (e.g., “Even when I don’t want to view pornography online, I feel

drawn to it.”), Emotional Distress (e.g., “I feel depressed after viewing pornography

online.”), and Access Efforts (e.g., “I have put off important priorities to view

pornography.”). Participants rate their agreement with these items on a scale of 1 (not at all)

to 7 (extremely). This measure was administered at both baseline and one year later. Items

were averaged.

Pornography use. At baseline, participants who reported pornography use within the

past six months were asked to estimate their average daily use of pornography on a scale of 0

to 12 hours. Due to the substantial positive skew of this variable (Skew for Study 1 = 6.4;

Study 2 = 6.9), cube root transformations33 were conducted to reduce skew (Skew for Study 1

= 0.8; Study 2 = 0.5) before analyses. Analyses were also conducted with the raw,

untransformed variable, producing virtually identical results. Final reported results reflect the

transformed variable.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Moral disapproval of pornography use. At baseline, the same four items used in

previous studies of moral disapproval of pornography use were included.23 These four items

include two non-religiously worded items (e.g., “Viewing pornography online would trouble

my conscience.”) and two more religiously worded items (e.g., “I believe that viewing

pornography online is a sin.”). Participants rated their agreement with statements on a scale

of 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). Items were averaged.

Religiousness. At baseline we included a modified (removing deity specific items)

version of Blaine and Crocker’s scale.34 This 4-item scale asks participants to rate their

agreement with statements such as, “Being a religious/spiritual person is important to me” on

a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). We also included a measure of

religious participation.35 This scale asks participants how frequently they engage in certain

religious behaviors within the past week (e.g., “Over the past week, how often have you

prayed?” or “Over the past week, how often have you attended religious services?”) on a

scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (multiple times per day). Consistent with prior research on this

topic,23 we standardized the items from both scales and averaged them into a general index of

religiousness.

Personality. At baseline, we included the Brief Self-Control Scale.36 This measure

requires participants to rate their agreement with statements such as, “I am good at resisting

temptation” on a scale of 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me). Items were averaged.

We also included the Psychological Entitlement Scale37 at baseline. This 9-item

measure requires participants to rate their agreement with items such as, “If I were on the

Titanic, I would deserve to be on the first lifeboat!” on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7

(strongly agree). Items were averaged.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Finally, we included the 8-item Neuroticism sub-scale of the Big Five Inventory-4438

at baseline. Participants rated their agreement with items such as “I worry a lot” on a scale of

1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items were averaged.

See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for all study variables (Range, M, SD,

Cronbach’s alpha).

Analytic Plan

Power tests were conducted using the PWR39 package for R Statistical Software.40 For

all analyses, acceptable power was determined to be .80 at an alpha level of 0.05.41 Cross-

sectional Pearson product-moment correlations were found to be sufficiently powered to

reliably detect small correlations for Sample 1 (r >= 0.07) and Sample 2 (r >= 0.10). Power

analyses for regression analyses with 7 independent variables found the sample sufficiently

powered to reliably detect even small effect sizes for Sample 1 (f2 = 0.01) and Sample 2 (f2 =

0.02). Longitudinally, we had sufficient power to detect Pearson correlations of moderate size

in Sample 1 (r >= 0.23) and Sample 2 (r >= 0.19), and we had sufficient power to detect

effect sizes of regression with 8 independent variables of moderate size in Sample 1 (f2 >=

0.11) and Sample 2 (f2 >= 0.08).

Although the majority of data were ordinal in nature (e.g. likert scales), we used linear

regression techniques assuming normally distributed outcome variables. 42 Analysis of

residuals from these regressions suggested that this approximation was reasonable. For cross-

sectional analyses. Pearson correlations were calculated between baseline variables in both

samples, using the psych package43 for R Statistical software. We also conducted a series of

simultaneous linear regressions in each sample, with the total CPUI-9 score and component

scale scores as dependent variables. We controlled for multiple comparisons using Holm

adjusted test statistics. This is a sequentially rejective version of the simple Bonferroni

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

correction for multiple comparisons and strongly controls the family-wise error rate at a set

alpha (alpha = 0.05 for this set of analyses).43

For longitudinal analyses, multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) was used to

determine if there were any differences between those who completed the follow-up and

those who did not on any key variables (e.g., CPUI-9; Pornography Use; Moral Disapproval;

Religiousness). Pearson correlations were computed between baseline variables and PA

variables at Time 2.

Subsequent to Pearson correlations, we entered variables into a series of two-step

regressions predicting perceived addiction and its component scores. In order to see how our

key variables of choice predicted PA over time, in the first step we entered baseline variables

of interest (i.e., personality variables, moral disapproval, religiousness, pornography use, and

male gender). In the second step, we included baseline levels of PA, to determine if our

variables of interest maintained a significant relationship with PA over time, even when

baseline PA was controlled statistically.

Results

Cross sectionally, in both samples, in Pearson correlations, pornography-related

variables were all consistently and positively related to each other (See Table 2). Similarly,

moral disapproval of pornography use and religiousness were consistently positively related

to the total CPUI-9 score, the Emotional Distress subscale, and the Perceived Compulsivity

sub-scale. Among included personality variables, in both samples psychological entitlement

was positively associated with the Access Efforts and the Perceived Compulsivity sub-scales,

and self-control was negatively associated with those two sub-scales.

In simultaneous regressions (See Table 3), in both samples, the only consistent

associates of daily pornography use were psychological entitlement and male gender. In both

samples, psychological entitlement emerged as a positive and self-control emerged as a

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

negative associate of the total CPUI-9 score, as well as the Access Efforts and Perceived

Compulsivity sub scales. Male gender and daily pornography use were consistently positively

related to the total CPUI-9 score, as well as the Access Efforts and Perceived Compulsivity

subscales. Moral disapproval, but not religiousness, was consistently positively associated

with the total CPUI-9 score and all component scales.

Longitudinal Analyses

MANOVA revealed no multivariate differences on key measures (i.e., Pornography

Use, PA, Moral Disapproval of Pornography, and Religiousness) between those who

completed the follow-up and those who did not in either sample.

In correlations between baseline variables and perceived addiction one year later (See

Table 4), the CPUI-9 and its component scales were all strongly and positively related to their

corresponding scores a year later. Similarly, moral disapproval and religiousness were each

positively and strongly related to the total CPUI-9 score, Perceived Compulsivity, and

Emotional Distress.

Two-step regression models were then conducted (see Table 5). During the first step

of each analysis, moral disapproval and male gender emerged as the only consistent

predictors of PA. In the second step, upon entry of baseline CPUI-9 scores, the only

consistent predictors of Time 2 CPUI-9 and subscale scores were baseline CPUI-9 scores and

male gender. Contrary to hypotheses, there was no observable relationship between baseline

pornography use and Time 2 CPUI-9 scores. Furthermore, the previously significant

relationships between Moral Disapproval and Time 2 PA were no longer statistically

significant when baseline levels of PA were entered into the regression.

Discussion

In cross-sectional data, consistent with our predictions and with prior literature,23 PA

and its component scores were largely associated with greater moral disapproval of internet

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

pornography use and more pornography use in general. Also consistent with prior literature,23

trait self-control negatively predicted unique variance in Perceived Compulsivity and Access

Efforts in both samples. We found no association between neuroticism and PA when other

variables were accounted for.14 Psychological entitlement was positively related to

pornography use, feelings of perceived compulsivity, and intensity of efforts to access.

Over a one year time span, the greatest predictor of PA was baseline levels of PA.

Yet, moral disapproval demonstrated strong associations with PA over time in correlational

analyses and in initial steps of regression analyses, before controlling for baseline PA.

Pornography use itself did not demonstrate a substantive or significant relationship with PA

over time, suggesting that use itself is not the primary driving factor in PA, consistent with

prior works demonstrating that frequency of pornography consumption was not a predictor of

seeking help for problematic pornography use.15, 44

Implications

Our findings suggest that, although PA may certainly be a function of realistic self-

appraisal in some cases, it is likely not always an accurate self-view but rather may be

exacerbated or maintained by moral scruples around pornography use. Why might this be the

case? As prior works have speculated,23 it plausible that, for religious individuals,

pornography use represents violation of deeply held beliefs, resulting in dissonance and

shame. In turn, these feelings of distress and shame may drive a pathological self-view,

leading to a view of self as addicted.

These findings bear implications for the accurate conceptualization and definition of

sexually-based behavioral addictions. Sexual behavior causing significant functional

impairment or psychological distress reflects the clinical hallmark of compulsive sexual

disorders.45 However, the morally charged nature of these domains means that some

individuals are likely to experience shame and guilt around their behaviors that may

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

complicate self-perceptions, leading to pathological interpretations of behavior. For these

individuals, there may be substantial distress and impairment—similar to what may be

observed in addictive disorders—but this distress might be secondary to pathological self-

views, rather than behavioral dysregulation. Indeed, very recent research has found that moral

incongruence regarding pornography use (i.e., believing pornography use is wrong but still

using it) is longitudinally associated with psychiatric distress.46 At present, we are unaware of

any other addictive disorder for which moral disapproval plays such a key role, indicating

that any discussion of the addictive nature of pornography must include a discussion of the

morally charged nature of the topic.

These conclusions further support the need to distinguish between perception and

reality when assessing an individual’s experience of pornography use. Clientele seeking

treatment for dysregulated pornography use may be accurately identifying a behavioral

problem themselves or they may be experiencing elevated perceptions of addiction or

dysregulation, secondary to moral qualms. Treatment solely targeted toward behavioral

change or addiction treatment (e.g., 12-step programs or behavior modification strategies

alone) may not fully address the nature of their psychopathology. More comprehensive

treatment may be necessary for many clients, addressing both problematic behaviors, as well

as problematic beliefs about those behaviors. Despite the plethora of popular literature

dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of pornography addiction, our findings point to the

need to be cautious in applying such labels to distressed individuals seeking mental health

treatment. Instead, there is a need for holistic and integrated assessments of sexuality, of

actual objective pornography use behaviors, subjective perceptions of addiction, and personal

morality or beliefs around such use.

Limitations and Future Directions

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Our work relied on self-report measures, the limitations of which are well-known.47

Our samples were taken from the general community, rather than a clinical population. In

prior studies of individuals seeking treatment for hypersexual behaviors, religiousness was

not related to symptoms.48 Future work should seek to examine these constructs specifically

in populations seeking treatment for pornography-related problems. We also noted that, by

restricting our analyses to only those who had used pornography within the past six months at

both time points (baseline and one year later), we may have omitted individuals who had

previously used pornography but had practice abstention for an extended period of time.

More importantly, we may have omitted individuals who had quit pornography use between

Time 1 and Time 2. Despite rather well-powered cross-sectional samples, our longitudinal

samples were considerably smaller, limiting our statistical power, additionally, by applying

Holm corrections to our analyses, we further limited this power. We also note that our

attrition rate at one-year post-baseline was substantial. Although no multivariate differences

were noted between those who returned and those who did not, attrition rates of fifty percent

do limit our findings. We also note that our surveys relied on reported daily use of

pornography in hours, whereas other studies15, 44 have measured frequency of use rather than

averages. Finally, samples were limited to adults in the U.S. Although somewhat diverse in

religious belief, our samples were more homogenous in racial/ethnic identity

(white/Caucasian) and sexual orientation (heterosexual). Future work should test these

constructs in populations that are more diverse in race/ethnicity and sexual orientation. Future

work would also be well-served to contrast trajectories of pornography use and PA between

religious believers and nonbelievers. Although some prior work has examined this topic

cross-sectionally, 25 examining how believers and nonbelievers interpret their own use of

pornography over time is likely to further illuminate the role of religiousness in predicting

PA. Despite these limitations, the present work represents a novel attempt to trace the

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

development of PA to internet pornography over time, with findings again highlighting the

role of religiousness and moral disapproval of pornography in contributing to the self-

perception of addiction to pornography.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the John Templeton Foundation (Grant #’s 36094

& 59916) in funding this project. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect

the views of the funding agencies and reflects the views of the authors.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

References

1

Harkness EL, Mullan B, Blaszczynski A. Association between pornography use and sexual

risk behaviors in adult consumers: a systematic review. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc

Netw. 2015 Feb 1;18(2):59-71.

2

Peter, J, & Valkenburg, PM (2016). Adolescents and pornography: a review of 20 years of

research. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(4-5), 509-531.

3

Arterburn S, Martinkus JB. Worthy of her trust: What you need to do to rebuild sexual

integrity and win her back. CO Springs, CO: WaterBrook Press; 2014.

4

Struthers WM. Wired for intimacy: How pornography hijacks the male brain. Downers

Grove, IL, IL: IVP Books; 2009.

5

Wilson G. Your Brain on Porn: Internet Pornography and the Emerging Science of

Addiction. Richmond, VA: Commonwealth Publishing; 2015.

6

Duffy A, Dawson DL, Nair RD. Pornography addiction in adults: A systematic review of

definitions and reported impact. J Sex Med. 2016 May 31; 13(5):760–777.

7

Kraus SW, Voon V, Potenza MN. Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an

addiction? Addiction. 2016 Dec 1;111(12):2097-106..

8

Ley DJ. Ethical porn for dicks: A man’s guide to responsible viewing pleasure. Berkeley,

CA: ThreeL Media; 2016.

9

Voros, F. (2009). The invention of addiction to pornography. Sexologies, 18(4), 243-246.

10

Reid RC. Additional challenges and issues in classifying compulsive sexual behavior as an

addiction. Addiction. 2016 Dec 1;111(12):2111-3.

11

Grant JE, Atmaca M, Fineberg NA, Fontenelle LF, Matsunaga H, Janardhan Reddy YC,

Simpson HB, Thomsen PH, Heuvel OA, Veale D, Woods DW. Impulse control

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

disorders and “behavioural addictions” in the ICD‐11. World Psychiatry. 2014 Jun

1;13(2):125-7.

12

Short MB, Black L, Smith AH, Wetterneck CT, Wells DE. A review of Internet

pornography use research: Methodology and content from the past 10 years.

Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012 Jan 1;15(1):13-23.

13

Grubbs JB, Volk F, Exline JJ, Pargament KI. Internet pornography use: PA, psychological

distress, and the validation of a brief measure. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015 Jan

2;41(1):83-106..

14

Blais-Lecours S, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Sabourin S, Godbout N. Cyberpornography: time

use, PA, sexual functioning, and sexual satisfaction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw.

2016 Nov 1;19(11):649-55.

15

Kraus SW, Martino S, Potenza MN. Clinical characteristics of men interested in seeking

treatment for use of pornography. J Behav Addict. 2016 Jun 27;5(2):169-78..

16

Grubbs JB, Stauner N, Exline JJ, Pargament KI, Lindberg MJ. PA to Internet pornography

and psychological distress: Examining relationships concurrently and over time.

Psychol Addict Behav. 2015 Dec;29(4):1056-067.

17

Bőthe B, Tóth-Király I, Orosz G. Clarifying the links among online gaming, internet use,

drinking motives, and online pornography use. Games for health journal. 2015 Apr

1;4(2):107-12.

18

Morelli M, Bianchi D, Baiocco R, Pezzuti L, Chirumbolo A. Sexting Behaviors and Cyber

Pornography Addiction Among Adolescents: the Moderating Role of Alcohol

Consumption. Sex Res Social Policy. 2017 Jun 1;14(2):113-21.

19

Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Blais-Lecours S, Labadie C, Bergeron S, Sabourin S, Godbout N.

Profiles of cyberpornography use and sexual well-being in adults. Sex Med. 2017 Jan

31;14(1):78-85.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

20

Wilt JA, Cooper EB, Grubbs JB, Exline JJ, Pargament KI. Associations of PA to internet

pornography with religious/spiritual and psychological functioning. Sexual Addiction

& Compulsivity. 2016 Apr 2;23(2-3):260-78.

21

Leonhardt, N. D., Willoughby, B. J., & Young-Petersen, B. (2017). Damaged goods:

Perception of pornography addiction as a mediator between religiosity and

relationship anxiety surrounding pornography use. The Journal of Sex Research,

Online First.

22

Grubbs JB, Exline JJ, Pargament KI, Volk F, Lindberg MJ. Internet pornography use, PA,

and religious/spiritual struggles. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016 Jun 28:1-3.

23

Grubbs JB, Exline JJ, Pargament KI, Hook JN, Carlisle RD. Transgression as addiction:

Religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of PA to pornography. Archives of

Sexual Behavior. 2015 Jan 1;44(1):125-36.

24

Egan V, Parmar R. Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and

compulsivity. J Sex Marital Ther, 2013 Sep 1;39(5):394-409.

25

Bradley DF, Grubbs JB, Uzdavines A, Exline JJ, Pargament KI. PA to Internet

Pornography among Religious Believers and Nonbelievers. Sexual Addiction &

Compulsivity. 2016 Apr 2;23(2-3):225-43.

26

Volk F, Thomas J, Sosin L, Jacob V, Moen C. Religiosity, Developmental Context, and

Sexual Shame in Pornography Users: A Serial Mediation Model. Sexual Addiction &

Compulsivity. 2016 Apr 2;23(2-3):244-59.

27

Grubbs JB, Exline JJ. Trait entitlement: A cognitive-personality source of vulnerability to

psychological distress. Psychol Bull. 2016 Nov;142(11):1204-226.

28

Baumeister RF, Catanese KR, Wallace HM. Conquest by force: A narcissistic reactance

theory of rape and sexual coercion. Rev Gen Psychol. 2002 Mar;6(1):92-135.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

29

Kasper TE, Short MB, Milam AC. Narcissism and internet pornography use. J Sex Marital

Ther. 2015 Sep 3;41(5):481-6..

30

Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon's Mechanical Turk a new source of

inexpensive, yet high-quality, data?. Perspectives on psychological science.

2011;6(1):3-5.

31

Paolacci G, Chandler J. Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant

pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014 Jun;23(3):184-8.

32

Shapiro DN, Chandler J, Mueller PA. Using Mechanical Turk to study clinical populations.

Clinical Psychological Science. 2013 Apr;1(2):213-20.

33

Mangiafico, S.S. 2016. Summary and Analysis of Extension Program Evaluation in R,

version 1.8.1 rcompanion.org/handbook/. (Pdf

version:rcompanion.org/documents/RHandbookProgramEvaluation.pdf.)

34

Blaine B, Crocker J. Religiousness, race, and psychological well-being: Exploring social

psychological mediators. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995 Oct;21(10):1031-41.

35

Exline JJ, Yali AM, Sanderson WC. Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious

strain in depression and suicidality. J Clin Psychol. 2000 Dec 1;56(12):1481-96..

36

Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self‐control predicts good adjustment, less

pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004 Apr 1;72(2):271-

324..

37

Campbell WK, Bonacci AM, Shelton J, Exline JJ, Bushman BJ. Psychological entitlement:

Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. J Pers Assess.

2004 Aug 1;83(1):29-45.

38

John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The big five inventory: Versions 4a and 54, institute of

personality and social research. University of California, Berkeley, CA. 1991.

39

Champely S. pwr: Basic functions for power analysis. R package version. 2012;1(1).

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

40

Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for

Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. 2017 Mar.

41

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992 Jul;112(1):155.

42

Norman G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in

health sciences education. 2010 Dec 1;15(5):625-32.

43

Revelle W. psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research.

Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. 2014 Aug;165.

44

Gola M, Lewczuk K, Skorko M. What matters: quantity or quality of pornography use?

Psychological and behavioral factors of seeking treatment for problematic

pornography use. J Sex Med. 2016 May 31;13(5):815-24..

45

Kraus SW, Voon V, Kor A, Potenza MN. Searching for clarity in muddy water: future

considerations for classifying compulsive sexual behavior as an addiction. Addiction.

2016 Dec 1;111(12):2113-4..

46

Perry, SL Pornography use and depressive symptoms: Examining the role of moral

incongruence. Society and Mental Health. (In Press)

47

Chan D (2008) So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In: Lance CE,

Vandenberg RJ, editors. Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends:

Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences. New York:

Psychology Press. pp. 309–336..

48

Reid RC, Carpenter BN, Hook JN. Investigating correlates of hypersexual behavior in

religious patients. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2016 Apr 2;23(2-3):296-312.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

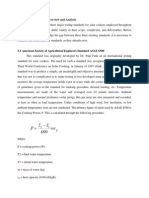

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for Included Variables

Study 1 Study 1

Time 1 Time 1

(N = 1,507) (N = 782)

Cronbach’s Cronbach’s

Range M SD α M SD α

CPUI-9 1-7 2.0 1.2 .86 1.6 0.9 .84

Access Efforts 1-7 1.8 1.2 .72 1.4 0.9 .65

Perceived Compulsivity 1-7 2.1 1.5 .86 1.4 1.1 .94

Emotional Distress 1-7 2.3 1.6 .90 1.9 1.5 .84

Daily Pornography Use

1-12 0.7 1.6 - 0.5 1.2 -

(in hours)†

Moral Disapproval 1-7 2.5 1.9 .96 2.2 1.9 .92

Religious Participation 0-5 2.0 0.9 .83 2.0 1.0 .82

Religious Belief Salience 0-10 5.8 3.6 .88 5.8 4.2 .88

Self-Control 1-5 3.0 0.5 .80 3.2 0.6 .89

Entitlement 1-7 3.1 1.2 .93 2.8 1.3 .92

Neuroticism 1-5 3.0 0.7 .82 2.8 0.9 .88

Time 2 Time 2

(N = 146) (N = 211)

CPUI-9 1-7 2.4 1.4 .90 1.7 0.9 .87

Access Efforts 1-7 2.4 1.7 .79 1.7 1.1 .66

Perceived compulsivity 1-7 1.9 1.3 .89 1.7 1.2 .92

Emotional Distress 1-7 2.9 2.1 .94 1.6 1.1 .81

†due to the skewed nature of this variable (Study 1 = 6.4; Study 2 = 6.9) cube root transformations

were conducted to reduce skew (Study 1 = 0.8; Study 2 = 0.5) before analyses. Results indicated no

differences in sign, relative size, or significance for any analyses using either the raw variable or the

transformed variable. In Table 1, reported results reflect the raw variable; all further reported results

throughout the manuscript reflect the transformed variable.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 2: Cross-Sectional Correlations and 95% Confidence Intervals between Baseline Measures

Study 1, N = 1,507

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1. CPUI-9 .76** .89** .84** .18** .68** .48** -.04 .07 .03

[.74, .78] [.88, .9] [.83, .86] [.13, .23] [.65, .70] [.44, .51] [-.09, .01] [.02, .12] [-.02, .08]

2. Access .66** .66** .39** .33** .27** .16** -.10** .22** .07

Efforts [.62, .7] [.63, .68] [.35, .43] [.28, .37] [.22, .31] [.12, .21] [-.15,-.06] [.17, .26] [.02, .11]

3. Perceived .83** .54** .59** .25** .51** .36** -.08* .10** .02

Compulsivity [.8, .85] [.49, .59] [.56, .62] [.2, .3] [.47, .54] [.31, .4] [-.13,-.04] [.05, .15] [-.03, .06]

4. Emotional .81** .23** .44** -.04 .81** .58** .05 -.07 .00

Study 2, N = 782

Distress [.78, .83] [.16, .29] [.39, .5] [-.09, .01] [.79, .82] [.55, .61] [.00, .10] [-.12,-.03] [-.04, .05]

5. Daily Porn. .22** .35** .30** -.02 -.10** -.11** -.07 .16** .01

Use [.15, .29] [.29, .41] [.24, .36] [-.09,.05] [-.15,-.05] [-.16,-.06] [-.12,-.02] [.11, .21] [-.04, .06]

6. Moral .58** .11** .36** .72** -.08 .73** .09** -.12** -.06

Disapproval [.53, .63] [.04, .18] [.3, .42] [.69, .75] [-.15,-.01] [.70, .75] [.04, .14] [-.17,-.07] [-.11,-.01]

.36** .08 .22** .44** -.06 .61** .21** -.13** -.09**

7. Religiousness [.3, .42] [.01, .15] [.15, .28] [.38, .49] [-.13, .01] [.57, .65] [.18, .24] [-.16, -.1] [-.12,-.06]

8. Self-Control -.07 -.14** -.10 .04 -.14** .12* .24** -.10** -.29**

[-.13, .01] [-.21,-.07] [-.17,-.03] [-.03, .11] [-.20,-.07] [.05, .19] [.18, .29] [-.13,-.06] [-.31,-.26]

.10 .13** .12* .02 .12* .01 .03 -.02 .03

9. Entitlement

[.03, .17] [.06, .2] [.05, .19] [-.04, .09] [.05, .19] [-.06, .08] [-.03, .09] [-.08, .04] [0, .06]

.06 .03 .03 .06 -.01 -.05 -.12** -.50** .01

10. Neuroticism

[-.01, .13] [-.04, .1] [-.04, .1] [-.01, .13] [-.08, .06] [-.12, .02] [-.18,-.06] [-.54,-.45] [-.05, .07]

†p < .10; *p <.05; **p < .01 with Holm adjusted test statistics.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 3: Simultaneous Multiple Regression for Perceived Addiction to Internet Pornography at Baseline using Baseline Measures

CPUI-9 Total Access Efforts Perceived Compulsivity Emotional Distress

Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample Sample Sample 1 Sample 2

1 2

β β β β β β β β

Self-Control -.08** -.07† -.10** .11* -.12** -.09* .00 .01

Entitlement .12** .07* .19** .09* .12** .08* .02 .01

Neuroticism .08** .09* .08** .02 .05 .06 .06** .11**

Pornography Use .22** .21** .31** .29** .27** .25** .03 .03

Moral Disapproval .72** .58** .35** .10* .54** .36** .82** .72**

Religiousness .02 .03 .00 .06* .04 .04 -.01 .00

Gender .09** .15** .09** .14** .15** .20** .01 .05

F 286.7** 89.9** 80.0** 23.6** 156.1** 45.1** 412.3** 126.6**

R2 .57 .45 .27 .18 .42 .29 .66 .53

f2 1.32 0.85 0.37 0.22 0.72 0.43 1.94 1.17

†p < .10; *p <.05; **p < .01 with Holm adjusted test statistics for multiple comparisons

F = F Value for ANOVA, R2= Variance Accounted for. f2 = Cohen’s f2, effect size for regression.

Study 1, N = 1,507; Study 2, N = 782

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 4: Pearson Correlations and 95% Confidence Intervals between Baseline Variables and PA at Time 2

CPUI-9 Access Efforts Perceived Compulsivity Emotional Distress

Time 2 Time 2 Time 2 Time 2

Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2

CPUI-9 .49** .77** .31** .57** .46** .74** .50** .55**

[.37, .59] [.70, .82] [.18, .44] [.47, .67] [.34, .57] [.67, .8] [.38, .6] [.44, .65]

Access Efforts .23* .47** .28** .58** .25* .44** .12 .13

[.08, .36] [.35, .58] [.14, .41] [.48, .67] [.10, .38] [.31, .55] [-.03, .26] [-.01, .28]

Perceived Compulsivity .39** .68** .29** .54** .42** .75** .33** .36**

[.26, .51] [.6, .76] [.16, .42] [.42, .63] [.29, .53] [.68, .81] [.19, .45] [.23, .49]

Emotional Distress .45** .64** .18 .28 .37** .54** .56** .74**

[.32, .56] [.54, .72] [.04, .32] [.13, .41] [.24, .49] [.42, .63] [.46, .65] [.67, .8]

Daily Pornography Use .13 .11 .13 .22 .18 .14 .05 -.09

[-.02, .28] [-.04, .25] [-.02, .28] [.08, .36] [.03, .33] [-.01, .28] [-.10, .21] [-.23, .06]

Moral Disapproval .46** .61** .14 .25* .42** .51** .57** .72**

[.33, .56] [.51, .69] [-.01, .28] [.11, .39] [.29, .53] [.39, .61] [.46, .66] [.65, .79]

Religiousness .43** .39** .15 .18 .38** .33** .53** .46**

[.3, .54] [.26, .51] [0, .29] [.03, .32] [.25, .50] [.19, .45] [.42, .63] [.33, .57]

Self-Control .03 .1 -.04 -.01 0 .12 .08 .13

[-.12, .17] [-.05, .24] [-.19, .1] [-.15, .14] [-.14, .15] [-.03, .26] [-.06, .23] [-.02, .27]

Entitlement .03 .14 .13 .16 .06 .18 -.07 .00

[-.12, .17] [-.01, .28] [-.01, .27] [.01, .3] [-.09, .2] [.04, .32] [-.22, .07] [-.15, .15]

Neuroticism -.14 -.06 -.11 -.07 -.14 -.09 -.12 .01

[-.28, .01] [-.21, .08] [-.25, .04] [-.22, .07] [-.28, .01] [-.24, .06] [-.26, .03] [-.13, .16]

†p < .10; *p <.05; **p < .01 with Holm adjusted test statistics

Study 1, N = 146; Study 2, N = 211

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 5: Simultaneous Multiple Regression and 95% CI Predicting Time 2 Perceived Addiction from Baseline Variables in Both Samples

T2 CPUI-9 T2 Access Efforts T2 Perceived Compulsivity T2 Emotional Distress

Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 1 Sample 2

Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step Step

1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2

β β β β β β β β β β β β β β β β

Self-

-.06 -.06 07 -.08 -.10 -.08 -.13 -.11 -.08 -.07 -.03 -.03 .00 -.02 .02 -.06

Cont.

Entitle. .05 .01 .15* .04 .11 .04 .14 .02 .07 .02 .19* .06 -.01 -.02 .04 .03

Neuro. .01 -.01 .02 -.01 -.02 -.06 -.03 -.05 .02 .01 .02 .01 .03 .00 .05 .02

Porn. Use .09 .02 .05 .00 .09 -.01 .17 .03 .14 .06 .06 .01 .03 .00 -.11 -.05

Moral

.35** .18 .56** .13 .16 -.02 .20 -.04 .34** .26 .45** .01 .42** .19 .71** .37**

Disapp.

Relig. .14 .09 .08 .10 .03 -.02 .11 .08 .13 .09 .08 .10 .18 .14 .02 .05

Gender .26** .21* .21** .14† .21 .17 .16 .08 .28** .24** .26** .15† .20** .16 .09 .11

*

T1: AE .02 .18 .16 .40** .03 .05 -.10 .00

T1: PC .20 .30** .19 .26* .22† .55** .14 -.11

T1: ED .17 .29** .13 .06 .02 .18 .30* .48**

R2 .32 .37 .45 .63 .12 .20 .17 .43 .33 .37 .37 .62 .39 .44 .54 .62

f2 0.47 0.59 0.82 1.70 0.14 0.25 0.20 0.75 0.49 0.59 0.59 1.63 0.64 0.79 1.17 1.63

ΔR 2

.05 .18 .08 .26 .04 .25 .05 .08

F for ΔR 10.3

2 **

4.0 **

19.7 **

28.2 **

2.9 **

4.9 **

4.9 **

25.0** 10.6** 3.1* 14.3** 36.9** 14.0** 4.8** 28.7** 11.1**

†p < .10; *p <.05; **p < .01. Holm-adjusted test-statistics.

AE = Access Efforts; PC = Perceived Compulsivity; ED = Emotional Distress

Study 1, N = 146; Study 2, N = 211

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Psychological Nature of Bullying and Its Determinants: A Study of Teenagers Living in the Country of GeorgiaD'EverandThe Psychological Nature of Bullying and Its Determinants: A Study of Teenagers Living in the Country of GeorgiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Self-Reported Addiction To Pornography in A Nationally Representative Sample: The Roles of Use Habits, Religiousness, and Moral IncongruenceDocument6 pagesSelf-Reported Addiction To Pornography in A Nationally Representative Sample: The Roles of Use Habits, Religiousness, and Moral IncongruencePetra KóródiPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 10 11 - MIR - PsyArXiv 2017 10 16T18 - 00 - 22.534ZDocument23 pages2017 10 11 - MIR - PsyArXiv 2017 10 16T18 - 00 - 22.534ZMohammad HadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Grubbs 2013Document26 pagesGrubbs 2013marzzoxPas encore d'évaluation

- Internet Pornography Use and Sexual Motivation: A Systematic Review and IntegrationDocument40 pagesInternet Pornography Use and Sexual Motivation: A Systematic Review and IntegrationtigraycatsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Contribution of ADHD and ADocument6 pagesThe Contribution of ADHD and AAsish DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Donevan2017 PDFDocument25 pagesDonevan2017 PDFsmansa123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pornography Consumption and Psychosomatic and Depressive Symptoms Among Swedish Adolescents: A Longitudinal StudyDocument10 pagesPornography Consumption and Psychosomatic and Depressive Symptoms Among Swedish Adolescents: A Longitudinal Studyted deangPas encore d'évaluation

- Cyberpornography: Time Use, Perceived Addiction, Sexual Functioning, and Sexual SatisfactionDocument8 pagesCyberpornography: Time Use, Perceived Addiction, Sexual Functioning, and Sexual SatisfactionLígia Gonçalves SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Pornography: Methodology and Key TheoriesDocument23 pagesEffects of Pornography: Methodology and Key Theoriesgarganell100% (1)

- The Role of Sexual Arousal Ratings and Psychological Psychiatric Symptims For Using Internet Sex Sites Excessively Brand2011 PDFDocument8 pagesThe Role of Sexual Arousal Ratings and Psychological Psychiatric Symptims For Using Internet Sex Sites Excessively Brand2011 PDFhh juiPas encore d'évaluation

- Teenagers and Online PornographyDocument13 pagesTeenagers and Online PornographymateocrislaurencePas encore d'évaluation

- Mardhatillah, A. (2017) .Document5 pagesMardhatillah, A. (2017) .FarahYumna PutriKamalPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S2213158220301455 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S2213158220301455 Mainaliexprace.1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lewczuk 2017Document12 pagesLewczuk 2017BarbaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Pornography Use and Depressive Symptoms: Examining The Role of Moral IncongruenceDocument19 pagesPornography Use and Depressive Symptoms: Examining The Role of Moral Incongruenceted deangPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Health Fact Sheet Flyer Two Sided Final With ColonDocument2 pagesPublic Health Fact Sheet Flyer Two Sided Final With Colonsantiago maciasPas encore d'évaluation

- A Meta-Analysis of Pornography Consumption and Actual Acts of Sexual Aggression in General Population StudiesDocument23 pagesA Meta-Analysis of Pornography Consumption and Actual Acts of Sexual Aggression in General Population Studiesaroa100% (1)

- Ffects of Pornography Addiction On Grade 11 StudentsDocument60 pagesFfects of Pornography Addiction On Grade 11 StudentsRia TabuacPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Negative Mood On Event-Related Potentials When Viewing Pornographic PicturesDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Negative Mood On Event-Related Potentials When Viewing Pornographic PicturescalfontibonPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Online Social NetwoDocument338 pagesEffects of Online Social NetwoZaid MarwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Naltrexone Short Report - Full ManuscriptDocument13 pagesNaltrexone Short Report - Full ManuscriptNeus Sangrós VidalPas encore d'évaluation

- Treatment For Problematic Pornography UseDocument11 pagesTreatment For Problematic Pornography UseRodrigo Prioli MendesPas encore d'évaluation

- Community Problem Report Rough DraftDocument5 pagesCommunity Problem Report Rough Draftapi-386283613Pas encore d'évaluation

- 10 1080@00224499 2021 1916422Document12 pages10 1080@00224499 2021 1916422Petra KóródiPas encore d'évaluation

- Draft ResearchDocument10 pagesDraft Researchrazaele200Pas encore d'évaluation

- Treatment For Problematic Pornography UseDocument11 pagesTreatment For Problematic Pornography UselubietasPas encore d'évaluation

- Pornography Addiction Literature Reviews: Sexual Scripting (Document5 pagesPornography Addiction Literature Reviews: Sexual Scripting (JB DarPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Porn On Youth 9Document4 pagesImpact of Porn On Youth 9terminolohiyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Treatment For Problematic Pornography UseDocument11 pagesTreatment For Problematic Pornography UseEdisio Vicente BarataPas encore d'évaluation

- Binge-Watching, Internet, and 'Faux-Fillment' - Our Addiction To Bread and CircusesDocument12 pagesBinge-Watching, Internet, and 'Faux-Fillment' - Our Addiction To Bread and CircusesJustin Bronzell100% (1)

- Chen2017 - Similarities and Differences in PsychologyDocument11 pagesChen2017 - Similarities and Differences in Psychologyhilda.marselaPas encore d'évaluation

- ThesisDocument11 pagesThesismae santosPas encore d'évaluation

- NPP 201778Document11 pagesNPP 201778Krisztián AklanPas encore d'évaluation

- 2021 Article 10386Document9 pages2021 Article 10386Afifah Az-ZahraPas encore d'évaluation

- Accepted Manuscript Pathways To Sex AddictionDocument38 pagesAccepted Manuscript Pathways To Sex AddictionReinaldo HerreraPas encore d'évaluation

- PSYC6213 Final Paper NotesDocument14 pagesPSYC6213 Final Paper NotesMiryam MPas encore d'évaluation

- Bodkin Et Al, 2019Document11 pagesBodkin Et Al, 2019calebdcarr628Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lotfi 2021Document5 pagesLotfi 2021Febry YordanPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Science Reports - 2021 - Lotfi - The Effectiveness of Intervention With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy On PornographyDocument5 pagesHealth Science Reports - 2021 - Lotfi - The Effectiveness of Intervention With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy On PornographyJonathan L SabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On Homelessness and Substance AbuseDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Homelessness and Substance AbuseafmznqfsclmgbePas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Watching Pornographic Videos To The Behaviour of StudentsDocument32 pagesEffects of Watching Pornographic Videos To The Behaviour of Studentsjenny sabas75% (4)

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Problematic Internet Pornography Use: A Randomized TrialDocument12 pagesAcceptance and Commitment Therapy For Problematic Internet Pornography Use: A Randomized TrialdgarciavalerioPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is The Relationship Among Religiosity, Self-Perceived Problematic Pornography Use, and Depression Over Time?Document29 pagesWhat Is The Relationship Among Religiosity, Self-Perceived Problematic Pornography Use, and Depression Over Time?Petra KóródiPas encore d'évaluation

- Adolescent Sexual Aggressiveness and Pornography Use: A Longitudinal AssessmentDocument11 pagesAdolescent Sexual Aggressiveness and Pornography Use: A Longitudinal AssessmentaroaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexual BehaviorDocument4 pagesSexual Behaviorgraceconogana1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Crosby Jesse M Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For 2016Document33 pagesCrosby Jesse M Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For 2016Sergio De PanfilisPas encore d'évaluation

- Ni Hms 937807Document32 pagesNi Hms 937807Gilbert SihombingPas encore d'évaluation

- The Problem and Its SettingDocument30 pagesThe Problem and Its SettingCharmaine MacayaPas encore d'évaluation

- 00-The Porn Crisis - This Generations Sexual OutletDocument25 pages00-The Porn Crisis - This Generations Sexual OutletRenato Sukno100% (1)

- Fpsyg 11 613244Document24 pagesFpsyg 11 613244rimbaudartiePas encore d'évaluation

- StudiesDocument4 pagesStudiesLettrice NovelstarPas encore d'évaluation

- Associations Between Pornography Exposure, Body Image and Sexual Body Image: A Systematic ReviewDocument18 pagesAssociations Between Pornography Exposure, Body Image and Sexual Body Image: A Systematic ReviewtigraycatsPas encore d'évaluation

- 2006 Article p100Document8 pages2006 Article p100jakub.studennyPas encore d'évaluation

- University Students Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Sexual OffendersDocument16 pagesUniversity Students Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Sexual Offendersapi-607589196Pas encore d'évaluation

- Statement of The ProblemDocument7 pagesStatement of The ProblemKen Dela CernaPas encore d'évaluation

- PosterDocument1 pagePosterapi-551489955Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research TopicDocument6 pagesResearch TopicensooooooooooPas encore d'évaluation

- 21 10.1177@0886260520915544Document17 pages21 10.1177@0886260520915544Camila SorianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Skill-Mix - A Flexible and Expandable Family of Evaluations For AI ModelsDocument33 pagesSkill-Mix - A Flexible and Expandable Family of Evaluations For AI Modelstimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training - by Ceshine Lee - Veritable - MediumDocument19 pagesImproving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training - by Ceshine Lee - Veritable - Mediumtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introducing ChatGPT IIDocument16 pagesIntroducing ChatGPT IItimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk Wants To Save Humanity. The Only Problem - PeopleDocument6 pagesElon Musk Wants To Save Humanity. The Only Problem - Peopletimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Weak To Strong GeneralizationDocument49 pagesWeak To Strong Generalizationbeifuwu8Pas encore d'évaluation

- How To Transfer Algorithmic Reasoning Knowledge To Learn New Algorithms?Document21 pagesHow To Transfer Algorithmic Reasoning Knowledge To Learn New Algorithms?timsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Applying Ai To Rebuild Middle Class JobsDocument22 pagesApplying Ai To Rebuild Middle Class Jobstimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mobile ALOHA - Learning Bimanual Mobile Manipulation With Low-Cost Whole-Body TeleoperationDocument20 pagesMobile ALOHA - Learning Bimanual Mobile Manipulation With Low-Cost Whole-Body Teleoperationtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Theory For Emergence of Complex Skills in Language ModelsDocument17 pagesA Theory For Emergence of Complex Skills in Language Modelstimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Generative AI Exists Because of The TransformerDocument52 pagesGenerative AI Exists Because of The Transformertimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Does GPT-4 Pass The Turing TestDocument25 pagesDoes GPT-4 Pass The Turing Testtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- I Am The One Who Would Awaken YouDocument5 pagesI Am The One Who Would Awaken Youtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Who's Harry Potter? Approximate Unlearning in LLMsDocument21 pagesWho's Harry Potter? Approximate Unlearning in LLMstimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- OpenVoice - Versatile Instant Voice CloningDocument7 pagesOpenVoice - Versatile Instant Voice Cloningtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Religion and ScienceDocument4 pagesReligion and Sciencetimsmith1081574100% (1)

- VLOGGER: Multimodal Diffusion For Embodied Avatar SynthesisDocument22 pagesVLOGGER: Multimodal Diffusion For Embodied Avatar SynthesisarvindkrvartiyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Affordable Travel Club Application-USDocument1 pageAffordable Travel Club Application-UStimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Linearity of Relation Decoding in Transformer Language ModelsDocument23 pagesLinearity of Relation Decoding in Transformer Language Modelstimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- TacticAI An AI Assistant For Football Tactics - Google DeepMindDocument9 pagesTacticAI An AI Assistant For Football Tactics - Google DeepMindtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Solution of The Zodiac Killer's 340-Character CipherDocument62 pagesThe Solution of The Zodiac Killer's 340-Character Ciphertimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Humankind Is Literally One FamilyDocument3 pagesHumankind Is Literally One Familytimsmith1081574100% (1)

- Humankind Is Literally One FamilyDocument3 pagesHumankind Is Literally One Familytimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Humankind Is Literally One FamilyDocument3 pagesHumankind Is Literally One Familytimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Affordable Travel Club Application-USDocument1 pageAffordable Travel Club Application-UStimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Cat Is Out of The Bag: Orientalism Anti-Blackness and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's BooksDocument51 pagesThe Cat Is Out of The Bag: Orientalism Anti-Blackness and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Bookstimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- And My Heart-Truth Is Obvious If The Heart Itself Is Seen With Open Eyes PDFDocument9 pagesAnd My Heart-Truth Is Obvious If The Heart Itself Is Seen With Open Eyes PDFtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Avatar Adi Da's Discussion of The Five-Sheath Structure of The Human Body-Mind-ComplexDocument8 pagesAvatar Adi Da's Discussion of The Five-Sheath Structure of The Human Body-Mind-Complextimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Explaining Illness With Evil: Pathogen Prevalence Fosters Moral VitalismDocument10 pagesExplaining Illness With Evil: Pathogen Prevalence Fosters Moral Vitalismtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Avatar Adi Da's Final Summary Description of His Dialogue With Swami MuktanandaDocument7 pagesAvatar Adi Da's Final Summary Description of His Dialogue With Swami Muktanandatimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Making Sense of and Healing Suffering Insights From Buddhism and Critical Social Science Ruben FloresDocument13 pagesMaking Sense of and Healing Suffering Insights From Buddhism and Critical Social Science Ruben Florestimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Egocentric Network Analysis 2023-09-08 00-41-04Document521 pagesEgocentric Network Analysis 2023-09-08 00-41-04Adrijana MiladinovicPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effect of Prill Specifications On Emulsion-ANFO BlendsDocument17 pagesThe Effect of Prill Specifications On Emulsion-ANFO BlendsChristian Alexis Rosas PelaezPas encore d'évaluation

- Predicting Stock Returns by Classifier EnsemblesDocument8 pagesPredicting Stock Returns by Classifier EnsemblesSercan KıraçPas encore d'évaluation

- Rosen-Ch02 Positive ADocument12 pagesRosen-Ch02 Positive APutri IndahSariPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Workload Analysis PDFDocument14 pagesTeaching Workload Analysis PDFAhmad Farhan Dwi PutraPas encore d'évaluation

- Datacamp All CoursesDocument10 pagesDatacamp All CoursesPrageet Surheley0% (1)

- Debt Ratio, Debt To Equity Ratio, Net Profit MarginDocument6 pagesDebt Ratio, Debt To Equity Ratio, Net Profit MarginAli AkPas encore d'évaluation

- HRP & RecruitmentDocument51 pagesHRP & RecruitmentDevansh DubeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Does Job Security Increase Job Satisfaction A StudDocument32 pagesDoes Job Security Increase Job Satisfaction A StudAnne Jennifer50% (2)

- Estimation of Technical Efficiency in Production Frontier ModelsDocument53 pagesEstimation of Technical Efficiency in Production Frontier ModelskPas encore d'évaluation

- Estimation of Relationships Between 85th Percentile Speed, Standard Deviation of Speed, Roadway and Roadside Geometry and Traffic Control in Freeway Work Zones PDFDocument24 pagesEstimation of Relationships Between 85th Percentile Speed, Standard Deviation of Speed, Roadway and Roadside Geometry and Traffic Control in Freeway Work Zones PDFBasilPas encore d'évaluation

- Applied Statistics From Bivariate Through Multivariate Techniques 2nd Edition Warner Test Bank DownloadDocument5 pagesApplied Statistics From Bivariate Through Multivariate Techniques 2nd Edition Warner Test Bank DownloadDominic Ezzelle100% (22)

- Sample Research ArticleDocument13 pagesSample Research ArticleDESIDERIO CAMITANPas encore d'évaluation

- Multiple Linear RegressionDocument14 pagesMultiple Linear RegressionCyn SyjucoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ed585260 PDFDocument8 pagesEd585260 PDFClayton BrásPas encore d'évaluation

- Mathematics in The Modern WorldDocument5 pagesMathematics in The Modern WorldVince BesarioPas encore d'évaluation

- AI and IoT Based Monitoring System For Increasing The Yield in Crop ProductionDocument5 pagesAI and IoT Based Monitoring System For Increasing The Yield in Crop ProductionMadhusudhan N MPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 14 - Section A - Mathcad SolutionsDocument56 pagesChapter 14 - Section A - Mathcad SolutionsKhalid M MohammedPas encore d'évaluation

- Project 1: Analyze The Healthcare Cost and Utilization in Wisconsin HospitalsDocument13 pagesProject 1: Analyze The Healthcare Cost and Utilization in Wisconsin HospitalsVandana H N0% (1)

- Lesson 13 Logistic RegressionDocument26 pagesLesson 13 Logistic RegressionNicolas SironneauPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumers' Trust in A Brand and The Link To BrandDocument30 pagesConsumers' Trust in A Brand and The Link To BrandAnnamaria KozmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter3 Testing StandardsDocument7 pagesChapter3 Testing StandardsappannusaPas encore d'évaluation

- MC5306 - Data Science ModelDocument1 pageMC5306 - Data Science ModelMsec McaPas encore d'évaluation

- Spatial Econometrics IntroductionDocument42 pagesSpatial Econometrics IntroductionMoniefMydomainPas encore d'évaluation

- Lederman, Maloney 2007Document32 pagesLederman, Maloney 2007L Laura Bernal HernándezPas encore d'évaluation

- Caseload ManagementDocument21 pagesCaseload ManagementNBPas encore d'évaluation

- Graphs in Regression Discontinuity Design in Stata or RDocument2 pagesGraphs in Regression Discontinuity Design in Stata or RYoung-Hoon SungPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Exam - Proba - 2022 - Sem01 - v1Document3 pagesFinal Exam - Proba - 2022 - Sem01 - v1Jay LeePas encore d'évaluation

- 2019-A New Semiparametric Weibull Cure Rate Model Fitting Different Behaviors Within GAMLSSDocument18 pages2019-A New Semiparametric Weibull Cure Rate Model Fitting Different Behaviors Within GAMLSSsssPas encore d'évaluation

- Jansen (Qualitative Survey) PDFDocument21 pagesJansen (Qualitative Survey) PDFChester ArcillaPas encore d'évaluation