Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gandhi C

Transféré par

saiTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gandhi C

Transféré par

saiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gandhi proceeded to Bombay but was too weak from an attack of influenza

to attend the Congress meeting. After talking for hours with Nehru,

both in Poona and Bombay, Gandhi wrote to him about "the sharp difference

of opinion that has arisen between us." Gandhi reaffirmed his own

faith in everything he had written thirty-five years ago in Hind Swaraj, and

wrote of how troubled he was by Jawaharlal's rejection of virtually all he

believed. "I believe that if India, and through India the world, is to achieve

real freedom," Gandhi informed Nehru, "we shall have to go and live in

the villages—in huts, not in palaces. Millions of people can never live in cities

and palaces ... in peace. Nor can they do so by killing one another, that

is, by resorting to violence and untruth."7 His "ideal village" still only existed

"in my imagination," Gandhi conceded. Nonetheless he outlined its

noble virtues and characteristics: "In this village of my dreams the villager

will not be dull. . . . He will not live like an animal in filth and darkness.

Men and women will live in freedom. . . . There will be no plague, no

cholera and no smallpox. Everyone will have to do body labour." He passionately

confessed his dream to Nehru, knowing that Jawaharlal was

young enough and strong enough to carry it to fruition in freedom after the

British left. They disagreed on many things, but "we both live only for India's

freedom," Gandhi told the man destined to be prime minister.

"Though I aspire to live up to 125 years rendering service, I am nevertheless

an old man, while you are comparatively young. That is why I have

said that you are my heir. ... I should at least understand my heir and my

heir in turn should understand me."8

Nehru was eager to oust the British by force, if they lacked sense

enough to leave quickly. That October in Bombay, Nehru called upon a

cheering crowd to "prepare" for the last "battle for freedom."9 Amrit told

Cripps that Gandhi alone could keep India's masses nonviolent, but he had

less control over Congress youth ready to fight at the behest of Nehru. The

British now made the political mistake of bringing captured officers of

Bose's Indian National Army to trial for treason in Delhi's Red Fort. Nehru

led their defense in a flamboyant trial, rousing popular revolutionary fervor

among Delhi's Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs, since all three religions were

represented by the INA defendants. Wavell feared that Nehru might try to

use Netaji Bose's popular militant mantra, Jai Hind! ("Victory to India") to

rouse his former troops in support of Congress's demands for the more

rapid transfer of power. Hindu-Muslim rioting rocked the slums of North

India's most crowded cities, from Bombay to Calcutta, as preparations began

for national assembly elections scheduled to start in December.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Payment AgreementDocument4 pagesPayment AgreementIvy PazPas encore d'évaluation

- A Meeting in The Dark - Ngugu Wa Thiong'oDocument1 pageA Meeting in The Dark - Ngugu Wa Thiong'oChristian Lee0% (1)

- Walhalla MemorialDocument9 pagesWalhalla Memorialeddd ererrPas encore d'évaluation

- Pres Roxas Culture ProfileDocument66 pagesPres Roxas Culture ProfileArnoldAlarcon100% (2)

- The Supremacy of The ConstitutionDocument24 pagesThe Supremacy of The ConstitutionJade FongPas encore d'évaluation

- Racca and Racca vs. Echague (January 2021) - Civil Law Succession Probate of Will PublicationDocument20 pagesRacca and Racca vs. Echague (January 2021) - Civil Law Succession Probate of Will Publicationjansen nacarPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. DionaldoDocument4 pagesPeople v. DionaldoejpPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Pp-3 Match Summary Dewa Cup 4Document4 pages1 Pp-3 Match Summary Dewa Cup 4Anak KentangPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument74 pagesUntitledmichael ayolwinePas encore d'évaluation

- Nuestra Senora de La Inmaculada Concepcion y Del Triunfo de La Cruz de MigpangiDocument2 pagesNuestra Senora de La Inmaculada Concepcion y Del Triunfo de La Cruz de MigpangilhemnavalPas encore d'évaluation

- Tamil Nadu Government Gazette: ExtraordinaryDocument2 pagesTamil Nadu Government Gazette: ExtraordinaryAnushya RamakrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- English Civil WarDocument48 pagesEnglish Civil WarsmrithiPas encore d'évaluation

- APPRAC Digests Rule 40Document10 pagesAPPRAC Digests Rule 40Stan AileronPas encore d'évaluation

- UK Home Office: LincolnshireDocument36 pagesUK Home Office: LincolnshireUK_HomeOfficePas encore d'évaluation

- Sample of Program of Instruction: Framework For The List of Competencies Required of Maneuver Units)Document23 pagesSample of Program of Instruction: Framework For The List of Competencies Required of Maneuver Units)Provincial DirectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Amended and Restated Declaration of Covenants Conditions and Restrictions For The Oaks Subdivision 3-31-20111Document27 pagesAmended and Restated Declaration of Covenants Conditions and Restrictions For The Oaks Subdivision 3-31-20111api-92979677Pas encore d'évaluation

- ACOG Practice Bulletin On Thyroid Disease in PregnancyDocument5 pagesACOG Practice Bulletin On Thyroid Disease in Pregnancygenerics54321Pas encore d'évaluation

- PenguinDocument4 pagesPenguinAngela FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Derek Jarvis v. Analytical Laboratory Services, 3rd Cir. (2012)Document6 pagesDerek Jarvis v. Analytical Laboratory Services, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Exclusionary RuleDocument1 pageExclusionary RuleHenry ManPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument80 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- University of San Carlos V CADocument1 pageUniversity of San Carlos V CATrisha Dela RosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Andrés Bonifacio Monument: (Caloocan City)Document11 pagesAndrés Bonifacio Monument: (Caloocan City)Anonymous SgUz9CEPDPas encore d'évaluation

- Public International Law Exam NotesDocument5 pagesPublic International Law Exam NotesAnonymous 2GgQ6hkXLPas encore d'évaluation

- HRC Corporate Equality Index 2018Document135 pagesHRC Corporate Equality Index 2018CrainsChicagoBusinessPas encore d'évaluation

- I:ame VS LittonDocument2 pagesI:ame VS LittonGenevieve MaglayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Westernclassicalplays 150602152319 Lva1 App6892Document52 pagesWesternclassicalplays 150602152319 Lva1 App6892Lleana PalesPas encore d'évaluation

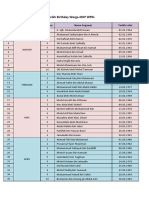

- Tarikh Besday 2023Document4 pagesTarikh Besday 2023Wan Firdaus Wan IdrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Plaint Dissolution of MarriageDocument3 pagesPlaint Dissolution of MarriageAmina AamerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Punjab Local Government Ordinance, 2001Document165 pagesThe Punjab Local Government Ordinance, 2001Rh_shakeelPas encore d'évaluation