Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Dreamers - Michael Dell

Transféré par

Simón TorresCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dreamers - Michael Dell

Transféré par

Simón TorresDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Staying Number One

Michael Dell built a successful computer business. What will it take

to remain on top?

From Reader's Digest

July 2007

A Novel Idea

When he was just 19, Michael Dell started the company that would

dominate the industry. The computer whiz had $1,000 and a novel

idea: to eliminate the retailer and sell directly to the consumer.

At the time, IBM personal computers sold in stores for about $3,000. After

taking them apart and rebuilding them, Dell realized the components could be purchased for one-fourth

the price. Even with added memory, bigger monitors and faster modems, the PCs could still be sold at a

handsome profit. Soon he was buying components in bulk to reduce the cost. A good business decision,

but it meant his room was starting to look like a mechanic's shop.

If Dell was a curious kid, he had his parents to thank. With his mother, a stockbroker, and his father, a

Houston orthodontist, dinner conversation frequently turned from what Michael and his two brothers were

doing in school to discussions of the economy and business opportunities.

"I was quite excited about the possibilities for personal computers and how they could change society.

Meanwhile, as a customer, I was disappointed that when I went to a computer store, the salespeople didn't

really know about computers. I had this idea to sell the products directly to the user over the phone. The

Internet," he adds, "was an unimaginable gift from heaven that came ten years later."

College plans and his parents' expectations intervened. But Michael Dell was determined. He drove off to

the University of Texas at Austin in August 1983 in a car he'd bought with earnings from selling newspa-

per subscriptions. He was surprised that his mother wasn't suspicious about the three computers in the

backseat. By November, rumors reached his parents that he wasn't attending classes. On a surprise visit to

Austin, they caught their son red-handed. Michael's father read him the riot act, then asked him what he

wanted to do with his life. He told his dad that he wanted to compete with IBM.

Although Michael agreed to focus on his studies, the business possibilities were too compelling to ignore,

and the timing couldn't have been better. The public was becoming more interested in computers and

wanted more sophisticated models, but no one was producing them. In early May, a week before his final

exams, Michael started Dell Computer Corporation with $1,000. He took his exams, then dropped out of

college at the end of his freshman year. It was time to try out his direct-to-the-customer business model.

Three years later, the company did a private placement, a stock offering to a small group of investors. "By

then," Dell says, "we had already achieved annual sales of about $150 million. I was 22 years old."

Tackling Tough Issues

Dell found out soon enough that necessity is the mother of invention. "I learned by doing and by making

mistakes. And I got smart people to help," he says. Today Dell is a $57 billion company, with the leading

market share in the United States.

In March 2004, at age 39, Dell stepped down as CEO (he remained chairman) and continued to focus on

research and technology. But soon there were signs of trouble. The company began losing market share

because of competition from much more aggressive rivals such as Hewlett-Packard and Lenovo. Dell was

also criticized for poor customer service. It's now facing investigations into its accounting practices by the

SEC and a U.S. Attorney.

This past January, the struggles forced Dell, now 42, to return to the company he founded, to tackle the

issues head-on. In 48 hours, he'd put in a new management team.

Of his marketing brainchild -- sell directly to the customer -- Dell told employees in an e-mail: "The Di-

rect Model has been a revolution, but it is not a religion." He intends to improve it and look for new

manufacturing and distribution models. The goal is to give customers what they need and make the tech-

nology simpler and easier to use.

As a technology leader, Michael Dell wants to use his position to solve society's bigger problems, like

health care. "If you go to your grocery store, there is more technology there than at your doctor's office.

Imagine the last time you went to the doctor, you see all those files. What is all that about? That is non-

sense. Try to take your medical information from one doctor to another. It is a system that can be dramati-

cally improved. Our industry has a big role to play."

Dell is also looking overseas, specifically at the needs of the next billion PC users. "We have a number of

new things going on in emerging markets in India, Poland, Brazil, the former Soviet Republics and

China."

Most importantly, Dell says he will deliver the kind of support his customers expect, both in tools and

technology. One new tool, called DellConnect, enables the tech staff to connect to the customer's com-

puter and fix problems on the spot or show the customer how to do it. In February, the company rolled out

IdeaStorm, a forum for users to brainstorm what works, what doesn't and what new features they'd like to

see introduced. "We take the customer's input and design the products and services," says Dell.

As for how long the reorganization will take, Dell says, "It took us some time to get into these challenges,

and it will take us some time to get out of them. I think 18 months."

If Dell needs any reminders that he can take the company to new heights, he can think back some 20

years earlier. "No one told me that we couldn't do it, and if they did, I wasn't listening." Recently he chal-

lenged employees. If they are to be competitive, they will need to make significant changes and take "well

thought-out risks." That's exactly what made Dell a success story.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Kill Me Deadly ScriptDocument75 pagesKill Me Deadly ScriptTrevorWang100% (2)

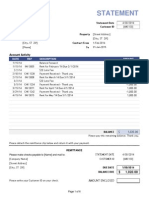

- Rental Billing StatementDocument6 pagesRental Billing StatementIsabel SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Direct From Dell: Strategies that Revolutionized an IndustryD'EverandDirect From Dell: Strategies that Revolutionized an IndustryÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (52)

- XCUITest 101 - Basics & Best PracticesDocument48 pagesXCUITest 101 - Basics & Best PracticesmljubevskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael DellDocument6 pagesMichael DellAhmedSaad647Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dell (PDF Library)Document16 pagesDell (PDF Library)qaiserabbaskhattakPas encore d'évaluation

- DELL ManagementDocument12 pagesDELL Managementaqib amjid khanPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study - 5Document2 pagesCase Study - 5Di RikuPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing SpotlightDocument2 pagesMarketing Spotlightgjgirl88Pas encore d'évaluation

- DellDocument33 pagesDellmerchantraza14Pas encore d'évaluation

- BRIEF HISTORY of DELLDocument4 pagesBRIEF HISTORY of DELLReynold Jose0% (1)

- Marketing Proposal EbookDocument29 pagesMarketing Proposal EbookaodsriharshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study MIS1 (Updated 092012)Document69 pagesCase Study MIS1 (Updated 092012)Trần Tiến100% (1)

- SOSTAC Applied To ECommerceDocument7 pagesSOSTAC Applied To ECommercejosephchainesPas encore d'évaluation

- Famous Mercedes Lorry Truck PDFDocument32 pagesFamous Mercedes Lorry Truck PDFNestor Humanez Guerrero100% (1)

- Assessment of IT General ControlsDocument13 pagesAssessment of IT General ControlsDeepa100% (2)

- Nanovation: How a Little Car Can Teach the World to Think Big and Act BoldD'EverandNanovation: How a Little Car Can Teach the World to Think Big and Act BoldÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Universiti Teknologi Mara Final Examination: Confidential CS/APR2008/CSC413Document4 pagesUniversiti Teknologi Mara Final Examination: Confidential CS/APR2008/CSC413Amient Kzi0% (1)

- Actionable Summary Based on the Book The Autobiography of Benjamin FranklinD'EverandActionable Summary Based on the Book The Autobiography of Benjamin FranklinPas encore d'évaluation

- Are You Ready To Change The World? Thoughts On Technology Leadership For The FutureD'EverandAre You Ready To Change The World? Thoughts On Technology Leadership For The FuturePas encore d'évaluation

- Get to the Point!: A Short and Snappy GuideD'EverandGet to the Point!: A Short and Snappy GuideÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- Internal Tech Conferences: Accelerate Multi-team LearningD'EverandInternal Tech Conferences: Accelerate Multi-team LearningPas encore d'évaluation

- The Swipe-Right Customer Experience: How to Attract, Engage, and Keep Customers in the Digital-First WorldD'EverandThe Swipe-Right Customer Experience: How to Attract, Engage, and Keep Customers in the Digital-First WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- Brag SummaryDocument7 pagesBrag Summarygeorgemtchua4385Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Rolling Desk: A Story of How Lasting Success Depends On A Purposeful And Well-Defined Company CultureD'EverandThe Rolling Desk: A Story of How Lasting Success Depends On A Purposeful And Well-Defined Company CulturePas encore d'évaluation

- What Does It Mean To Lead ITDocument17 pagesWhat Does It Mean To Lead ITakhileshchaturvediPas encore d'évaluation

- The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of PovertyD'EverandThe Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of PovertyÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- "Direct From Dell": Book Review OnDocument11 pages"Direct From Dell": Book Review OnJayan KrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Dell AbiyDocument9 pagesMichael Dell AbiyteshomePas encore d'évaluation

- 872-Article Text-3439-1-10-20110106Document8 pages872-Article Text-3439-1-10-20110106temp tempPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction of Michael DellDocument13 pagesIntroduction of Michael DellNikita_1992Pas encore d'évaluation

- Haripur University Assignment On: Entrepeneur Michael Dell Submitted To: Sir MahfozDocument3 pagesHaripur University Assignment On: Entrepeneur Michael Dell Submitted To: Sir MahfozM Aqeel Akhtar JajjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Saul Dell - CompressDocument21 pagesMichael Saul Dell - CompressjjmzrjwkdrwsgrprnzPas encore d'évaluation

- SeriesDocument3 pagesSeriesZekria Noori AfghanPas encore d'évaluation

- Salvatore's Managerial Economics: Principles and Worldwide Applications, 8th International Edition Chapter 2: The Education of Michael DellDocument5 pagesSalvatore's Managerial Economics: Principles and Worldwide Applications, 8th International Edition Chapter 2: The Education of Michael DellE. Bhargav KrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- WEB: Managerial Economics: Principles and Worldwide Applications, 7 Ed. 2: The Education of Michael DellDocument5 pagesWEB: Managerial Economics: Principles and Worldwide Applications, 7 Ed. 2: The Education of Michael DellKaran GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell Case StudyDocument4 pagesDell Case StudyDua Rehman KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Name:Hamidullah Tani S T: 1 3 0 4 0 8 0 5 3 TeacherDocument16 pagesName:Hamidullah Tani S T: 1 3 0 4 0 8 0 5 3 TeacherhamidPas encore d'évaluation

- BB-10-35 DellDocument4 pagesBB-10-35 Dellhinabatool777_651379Pas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Dell ThesisDocument7 pagesMichael Dell Thesisfc50ex0j100% (2)

- A Report On A Business Leader Micheal deDocument21 pagesA Report On A Business Leader Micheal deAl Jazhim Khan MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparative Study On Consumer Buying Behaviour Towards Dell Laptop & Other Laptop With Reference To Gondia CityDocument4 pagesA Comparative Study On Consumer Buying Behaviour Towards Dell Laptop & Other Laptop With Reference To Gondia CityujwaljaiswalPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell Group 2Document14 pagesDell Group 2Ayush KhandeliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bill GatesDocument3 pagesBill GatesMohamed Tayeb SELTPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell's Success From A Strategic Management PerspectiveDocument5 pagesDell's Success From A Strategic Management PerspectiveSarthak GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Where Dell Went WrongDocument2 pagesWhere Dell Went WrongThenmozhi RasuPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Life and Education: Orthodontist Houston, Texas High School Equivalency ExamDocument8 pagesEarly Life and Education: Orthodontist Houston, Texas High School Equivalency ExamPrabhjyot ChhabraPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 8Document26 pagesWeek 8balakumaransanjeevanPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Saul DellDocument4 pagesMichael Saul DellKartik BhatiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell Computer CorporationDocument14 pagesDell Computer CorporationĐiền VũPas encore d'évaluation

- A Case Study On: Submitted To: Submitted byDocument18 pagesA Case Study On: Submitted To: Submitted bySumit PhougatPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell Managing Working CapitalDocument8 pagesDell Managing Working CapitalWendy LowPas encore d'évaluation

- C4ca4case Study - Dell Computer Corporation - Strategy and ChallengesDocument20 pagesC4ca4case Study - Dell Computer Corporation - Strategy and ChallengesSonali YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell Is A Computer Company Founded in 1984 by Michael SDocument6 pagesDell Is A Computer Company Founded in 1984 by Michael SAltaf HossenPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell CaseDocument11 pagesDell CaseRestles HartPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study-S.MDocument3 pagesCase Study-S.Mjaveria_nabihaPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing in Dell and HP: Report Authored by Abdul Muizz, Areel Bhatti, Ahmed Khan Afridi and Fatima KifayatDocument12 pagesMarketing in Dell and HP: Report Authored by Abdul Muizz, Areel Bhatti, Ahmed Khan Afridi and Fatima KifayatFatima KifayatPas encore d'évaluation

- Matching DellDocument10 pagesMatching DellOng Wei KiongPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell CaseDocument1 pageDell CaseLavil Zavala GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell MinDocument7 pagesDell MinRosyasmin Abu BakarPas encore d'évaluation

- E-Marketing Dell Case StudyDocument21 pagesE-Marketing Dell Case StudykingjanuariusPas encore d'évaluation

- Dell Computers Exercise Essence of StrategyDocument3 pagesDell Computers Exercise Essence of StrategySahil Sahni100% (2)

- Seattle Retirement System Request For Proposal For Private Equity ConsultantDocument83 pagesSeattle Retirement System Request For Proposal For Private Equity ConsultantMCW0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Air France KLMDocument3 pagesAir France KLMAnton RichardPas encore d'évaluation

- Service Action 0S318 2010 Transit 2.2 Diesel - Intercooler To TurboDocument6 pagesService Action 0S318 2010 Transit 2.2 Diesel - Intercooler To TurboSanan Mammadov100% (1)

- IT ITeS Growth Corridor Series Bangalore ORR PDFDocument16 pagesIT ITeS Growth Corridor Series Bangalore ORR PDFmandapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- SoH Optimizations 2014-10-24Document37 pagesSoH Optimizations 2014-10-24MariusPas encore d'évaluation

- W7 Marketing Strategy DistributionDocument6 pagesW7 Marketing Strategy DistributionJennifer BrownPas encore d'évaluation

- SP Manual RevisedDocument279 pagesSP Manual Revisedkjkrishnan100% (1)

- FM Approvals Certification MarksDocument3 pagesFM Approvals Certification MarksAndiniPermanaPas encore d'évaluation

- CSP 900ipl 4 - I2r16pDocument1 574 pagesCSP 900ipl 4 - I2r16probiny100% (1)

- Client File ListDocument10 pagesClient File ListSheyla Edith Asanza AlvaradoPas encore d'évaluation

- VAT Reconcilation Forein (3) 2Document28 pagesVAT Reconcilation Forein (3) 2Bani SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- About Godfrey Phillips IndiaDocument17 pagesAbout Godfrey Phillips IndiaMohammad FaizanPas encore d'évaluation

- Reliance BCG Matrix EmmanuelDocument24 pagesReliance BCG Matrix Emmanuelsubhojitkarmakar10100% (1)

- The Trust Advantage: How To Win With Big DataDocument18 pagesThe Trust Advantage: How To Win With Big Datahungbkpro90Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 13 IntaccDocument2 pagesChapter 13 IntaccJhuliane RalphPas encore d'évaluation

- Confidential Disclosure Agreement - SimpleDocument3 pagesConfidential Disclosure Agreement - SimpledenvergamlosenPas encore d'évaluation

- 2044IATF BDocument3 pages2044IATF BKumaravelPas encore d'évaluation

- LEXICON Command Reference ManualDocument48 pagesLEXICON Command Reference ManualgunkerenPas encore d'évaluation

- Host Recommendations For 3.1.x 3PAR OS Upgrades - v3.1Document14 pagesHost Recommendations For 3.1.x 3PAR OS Upgrades - v3.1DragosDorobantuPas encore d'évaluation

- AusAid Visibility and RecognitionDocument12 pagesAusAid Visibility and RecognitionmarcheinPas encore d'évaluation

- The Star-Spangled BannerDocument9 pagesThe Star-Spangled BannerUdit BakshiPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Copyright Transfer Aggrement Journal SBM ITBDocument2 pages01 Copyright Transfer Aggrement Journal SBM ITBinget umurPas encore d'évaluation

- Sk39 Plaintiff RmlnluDocument33 pagesSk39 Plaintiff RmlnluChirag AhluwaliaPas encore d'évaluation