Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The French Colonial Period

Transféré par

Laura IoanaCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The French Colonial Period

Transféré par

Laura IoanaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The French colonial period, which for Algeria lasted 132 years (1830-1962) has introduced many changes

that

have left their imprints on the built environment, the cultural identity of the indigenous population and their social

make-up. On the one hand, urban developments during this period were primarily for the benefit of the European

settlers and consisted of apartment blocks and villa neighbourhoods following European architectural styles and

conforming to their standards. At times, the historic city fabric was demolished to clear the way for such

interventions. On the other hand, rural migration to the cities, whether be it forced by the colonial administration,

encouraged or simply for economic reasons, has led to the proliferation of large squatter settlements (or

bidonvilles) around the colonial cities (Edwards et al. 2006). The situation reached a critical level in terms of

housing shortage after the Second World War due to the indigenous population growth, which jumped from 23 %

in 1906 to reach 51.4 % by 1954 (Hadjri and Osmani, 2009). To face this problem, the French administration

launched a program for the construction of new neighbourhoods, in Algiers, to house the indigenous population.

This initiative resulted in projects such as ‘Climat de France’ and ‘Djenan El Hassan’ by French architects

Pouillon for the former and Simounet for the latter, which were completed in 1957 and 1958 respectively (Figs 3-

4). In an attempt to be seen to deal more efficiently with the housing crisis by the colonial administration, this

initiative was replaced by the ‘Plan de Constantine’ launched in 1958, as an urgent operation for the construction

of big scale projects especially social housing (50,000 units per year) named as ‘Les Grands Ensembles’. The plan

was highly criticised for being more concerned with quantity than quality; the lack of reference to the site and the

local character, however the circumstances at the time didn’t allow any place for debate. It resulted in urban

developments lacking spatial quality and with little or no reference to the traditional built heritage. Unfortunately

this continued to exist in post independence Algeria (EAG-CERTUC, 2003). After more than half a century of

independence, the built environment in Algeria is lacking both the architectural qualities and the cultural relevance.

This situation is often identified as a contributor to what became of the traditional courtyard urban dwelling, such

that of the Casbah in Algiers, as a forgotten heritage that is very expensive to keep and maintain. It reached a point

where it needs to be “rehabilitated both physically and socially. The mere renovation of its physical condition will

not improve its reputation and attract national and international visitors and investors unless the social and cultural

problems are tackled and resolved in Full” (Elsheshtawy, 2009).

The courtyard house, regardless of its origin, has evolved into a domestic built form that is responsive to its multi-

determinant context. Chief among these are climate and culture (Rapoport, 1969). In the forthcoming sections,

both these determinant will be discussed by means of a number of examples from the literature and some analysis

and discussion of data obtained by direct measurements in the field.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Property That Gave Origin To The Phenomena That Karl Marx Defined As PrimitiveDocument1 pageProperty That Gave Origin To The Phenomena That Karl Marx Defined As PrimitiveLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Of The Jus Publicum Europaeum, Translated by GL Ulmen (Candor, NY: Telos Press, 2006)Document1 pageOf The Jus Publicum Europaeum, Translated by GL Ulmen (Candor, NY: Telos Press, 2006)Laura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- TERRITORYDocument1 pageTERRITORYLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Socio-Cultural Significance of The Courtyard HouseDocument1 pageThe Socio-Cultural Significance of The Courtyard HouseLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Who Are The Stakeholders - Diagram PDFDocument2 pagesWho Are The Stakeholders - Diagram PDFLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- ALMOST NOTHING Mies Van Der Rohe and His "Three Courtyards House"Document4 pagesALMOST NOTHING Mies Van Der Rohe and His "Three Courtyards House"Laura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Courtyard House of CordobaDocument1 pageThe Courtyard House of CordobaLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Courtyard Form and ElementsDocument1 pageCourtyard Form and ElementsLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Courtyard BenefitsDocument2 pagesCourtyard BenefitsLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Urban Courtyard HouseDocument2 pagesThe Urban Courtyard HouseLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- 4.12 The Origin of The Classic Four Square' (Chahar Bagh) May Never Be Determined. It CouldDocument1 page4.12 The Origin of The Classic Four Square' (Chahar Bagh) May Never Be Determined. It CouldLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Of and Use in Buildings (Brown In: House and Environment Environment CanDocument1 pageOf and Use in Buildings (Brown In: House and Environment Environment CanLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- GseducationalversionDocument4 pagesGseducationalversionLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- EAHN2014abstracts PDFDocument121 pagesEAHN2014abstracts PDFLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Influence of Ancient Egyptian GardensDocument2 pagesThe Influence of Ancient Egyptian GardensLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Normative Laborator de RestaurareDocument1 pageNormative Laborator de RestaurareLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- One Criterion For Courtyard Houses Then Must Be The Nature of The Privacy Mechanism UsedDocument1 pageOne Criterion For Courtyard Houses Then Must Be The Nature of The Privacy Mechanism UsedLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

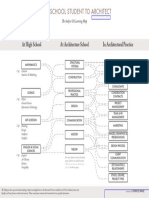

- PORTICO - The High School Student To Architect Subject and Learning Map PDFDocument1 pagePORTICO - The High School Student To Architect Subject and Learning Map PDFLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Facade HatchDocument1 pageFacade HatchLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- First IndesignDocument33 pagesFirst IndesignLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Final FlatDocument1 pageFinal FlatLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing Ideals in Architecture - From CIAM To Team XDocument3 pagesChanging Ideals in Architecture - From CIAM To Team XLaura IoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Notice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Red Dog Mine Extension-Aqqaluk Project, AKDocument1 pageNotice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Red Dog Mine Extension-Aqqaluk Project, AKJustia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 Strategic Planning Process (The External EnvironmeDocument28 pagesChapter 3 Strategic Planning Process (The External EnvironmeShanizam Mohamad Poat100% (1)

- DRRM Tagbilaran CityDocument22 pagesDRRM Tagbilaran CityGerard Lavadia100% (2)

- Storm Water Management Plan: Executive SummaryDocument171 pagesStorm Water Management Plan: Executive SummarySean CrossPas encore d'évaluation

- 28 08 2015lasanod Hospital Water Supply Design ReportDocument5 pages28 08 2015lasanod Hospital Water Supply Design ReportsubxaanalahPas encore d'évaluation

- Food Security PPT 21-30Document41 pagesFood Security PPT 21-30Savya Jaiswal100% (2)

- King Report On Corporate GovernanceDocument2 pagesKing Report On Corporate GovernanceKDMonteza100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Environmental Monitoring Officer (EMO) Activity ReportDocument4 pagesEnvironmental Monitoring Officer (EMO) Activity ReportMaricel RamiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Runako Charles: Financial Incentives For Waste Reduction in The UKDocument14 pagesRunako Charles: Financial Incentives For Waste Reduction in The UKRC85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Water Equity in TourismDocument17 pagesWater Equity in TourismarchitetorePas encore d'évaluation

- Bawasa Feasibility StudyDocument4 pagesBawasa Feasibility StudyJologs Jr LogenioPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergent or Prescriptive FormulationDocument10 pagesEmergent or Prescriptive FormulationDave Dearing100% (1)

- AEMAS National Council Seminar 21mar2011Document33 pagesAEMAS National Council Seminar 21mar2011Hishamudin IbrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Daniels Ib13 01Document19 pagesDaniels Ib13 01Nitin DhimanPas encore d'évaluation

- Community PsychologyDocument5 pagesCommunity PsychologyKilliam WettlerPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Management Bureau: Weekly Investigation ReportDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Management Bureau: Weekly Investigation ReportAngelica Valdez BautoPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of El Nino On The Agua Operations in Toril, Davao CityDocument7 pagesEffects of El Nino On The Agua Operations in Toril, Davao CityJong AbearPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Group Project - Group1Document37 pagesGroup Project - Group1ashe zinabPas encore d'évaluation

- Full Text Jairam R 2180847aDocument8 pagesFull Text Jairam R 2180847ahercuPas encore d'évaluation

- Certificate 1Document6 pagesCertificate 1parikshtihPas encore d'évaluation

- Management, Leadership, Political Lessons From Chanakya NitiDocument6 pagesManagement, Leadership, Political Lessons From Chanakya Nitikapilof2010Pas encore d'évaluation

- Water Safety and Conservation Awareness SeminarDocument16 pagesWater Safety and Conservation Awareness Seminaritskimheeey0% (1)

- Prova 770Document32 pagesProva 770Marcelo MorettoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sustainable Development: Environmental Planning, Laws and Impact AssessmentDocument16 pagesSustainable Development: Environmental Planning, Laws and Impact AssessmentMarielle BrionesPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing Nature of Managerial WorkDocument10 pagesChanging Nature of Managerial WorkakramPas encore d'évaluation

- PESTLE Analysis CIPDDocument1 pagePESTLE Analysis CIPDAhmed RaajPas encore d'évaluation

- A Rizal Park ExperienceDocument7 pagesA Rizal Park ExperienceseamajorPas encore d'évaluation

- Illinois Environmental Council 2017 ScorecardDocument6 pagesIllinois Environmental Council 2017 ScorecardJonah MeadowsPas encore d'évaluation

- GHM, H, KJDocument9 pagesGHM, H, KJCassandra Basco MalabPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisD'EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (49)

- Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureD'EverandDunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (19)

- The Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarD'EverandThe Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (63)

- Hubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyD'EverandHubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (23)

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorD'EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (77)