Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Task Based Language Teaching in A Learner-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

Transféré par

Ngân NguyễnTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Task Based Language Teaching in A Learner-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

Transféré par

Ngân NguyễnDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Task Based Language Teaching in a Learner-Centered ESP

Setting: A Case Study

Phoenix Lundstrom

Kapiolani Community

An instructional program, designed to assist a Japanese

businessman improve his letter writing skills, was developed using

task-based language leaming in a learner-centered environment.

Using this protocol, the leamer accomplished 50% of his stated

goals during the 14 week instructional period. The results strongly

indicate that the inclusión ofnegotiation in a task-based leaming

setting greatly enhanced the ability of the learner to articúlate

and meet his goals. Befare this technique is generalized to other

ESP programs, however, additional studies using a variety of

small-group settings, discourse requirements, and teaching

personalities should be conducted.

1. Introduction

English for specific purposes (ESP) focuses directly and specifically on the

reason(s) the leamer has for acquiring the language (Grosse, 1988a; Hristova,

1990; Hutchinson & Waters, 1987; Robinson, 1980). Krahnke (1987:61)

considered task-based instruction appropriate in ESP because learners "have a

clear and immediate need to use language for a well-defined purpose." Even

though the literature did not suggest it, the addition of learner-centered

negotiation of the curriculum described by Hutchinson and Waters (1987), could

créate a result-focused ESP curriculum in which the student has a strongly vested

interest. The salient features of both approaches were melded into a coherent

ESP program for a management level Japanese businessman, the results of which

are reportad here as a case study.

1.1 Task-based language learning

The twin goals of ESP (efficient delivery of services and relevance' of services

to the learner goals) are consistent with three facets of task-based language

learning: needs analysis; problem-solving activities; small-group work.

1 Relevance of the instruction to learner needs and desired outcomes may promote a high degree of success

in ESP(Grosse, 1988a; Johns&Dudley-Evans, 1991;Kim, 1992). A high level of relevance may, inturn,

act as a significant source of motivation (Crookes & Schmidt, 1989).

Revista d e L e n g u a s p a r a Fines Específicos N° 3 (1996) 201

Phoenix Lundstrom

1.1.1 Needs Analysis

ESP, as a situation-specific program, necessarily requires a comprehensive

needs analysis (Center for Applied Linguistics, 1985; Hutchinson & Waters,

1987; Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1991; Schmidt, 1981)^ involving the employer

and the employee. The completed needs analysis should provide the following:

1. task analysis of the target situation and the skills required

2. language required to appropriately perform in the target situation

3. gap between the current skills of the leamer and those required in the

target situation (This determination will inform the entry point for instruction.)

4 leamer assessment of the goal and gaps

1.1.2 Problem-solving

Problem-solving (Grosse, 1988a, 1988b; Long, 1989), problem-posing

(Auerbach & Burgess, 1989) and goal-orientation for ESP (Swales, 1990), créate

an intentional and productive focus on workplace-relevant meaning. Use of

the target language is supported by the processes of investigation, discussion

and action relating to the task. The target language, first used in the classroom,

is generalizable to the workplace.

1.1.3 Group work

Long & Porter (1985) and Long (1989) suggest that group work may yield a

higher quality of leamer talk through increased opportunities for practice. Grosse

(1988a) concurs, specifically suggesting small-group work for the ESP

classroom. Both the clear focus of the interactions and the opportunities for

individual attention address the affective needs of the leamer and further motívate

the learner in an already motivation-rich environment.

2 Task analysis is both product and process (identification, description and sequencing of all of tlie

target language that is a part of the target behavior). The resulting documentation can serve as a

comprehensive task description, a sequenced task syllabus, a tool for assigning the appropriate entry point

for instruction, and an assessment tool for skill mastery (McCormick, 1990: see Bell, 1981; see also

Mich. State Dept of Education Vocational-Technical Service task lists ERIC Documents ED 242901 -11,

259151-63). In addition to listing the relevant language and job-specific non-transferable skills it

should include potentially transferable skills, processes and language (Prince, 1984).

202 Revista d e L e n g u a s p a r a Fines Específicos N - 3 (1996)

Task Based Language Teaching in a Leamer-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

1.2 Learner-Centered Processes

The leamer-centered process emphasizes relevance of the program to leamer

needs (Auerbach, 1993), a view shared by ESP programs. Where

leamer-centered programs appear to diverge from ESP and task-based language

learning, is curriculum development. In the learner-centered environment,

learner participation begins with curriculum development (Auerbach, 1993;

Hutchinson & Waters, 1987) and in the task-based language learning setting,

learner participation begins with the needs analysis.

1.3 Negotiation

One área accepted by both task-based language learning and the leamer-centered

approach as a necessary condition is negotiation. Whether defined

psycho-hnguistically as the request for clarification, subsequent Identification and

repair of a message (Pica, 1989) or pragmatically as the process of bringing about

agreement, negotiation offers rich opportunities to use the leamer's current linguistic

resources as well as the emerging target language. In the leamer-centered ESP

environment envisioned by Hutchinson and Waters (1987), negotiation of the

curriculum enhances the relevance of the program to the leamer A syllabus designed

to promote the amount and quality of negotiation (Mohán, 1990) might include

negotiation of outcome as well as meaning (Crookes & Rulon, 1985), two-way

tasks that are purposeful i.e. focus on meaning (Long & Porter, 1985; Nobuyoshi &

Ellis, 1993; Nunan, 1993), and negotiation for meaning between the leamer and a

more competent interlocutor (Crookes & Rulon, 1985; Kumaravadivelu, 1991;

Long, in press). Negotiation between leamer and teacher is further enhanced when

the roles of expert and novice are shared: leamer descriptions of their hfe experiences

provide opportunities to negotiate for meaning (Crookes & Rulon, 1985; Delpit,

1988). Negotiation opportunities from the curriculum outward form an enhanced

communicative environment which encourages the acquisition of the target language.

1.4 Case Study

For this project, an environment was engineered to provide the máximum

amount of negotiation for meaning and content during needs analysis, curriculum

design and task-completion phases. Consequently, this setting required extensive

Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N- 3 (1996) 203

Phoenix Lundstrom

small-group task-based work between the leamer and the interviewer^ who shared

the roles of expert and novice. The meta-level focus was on the development of

a specific work-place relatad rhetorical form.

2. Method

2.1 Subject

The subject was a 39 year oíd Japanese male enrolled in a work-place literacy

program. The general manager of a Japanese tour company branch office, he

had 10 years of formal English instruction in Japan and had been in the United

States for 2 years. Testing" and assessment done by the literacy program indicated

that the learner was moderately fluent. His grammar use reflected problems

with article use, subject-verb agreement, and the tense system, áreas that are

typically resistant to early changa for Japanese native speakers.

2.2 Methodology

The interview format, in a setting that was socially engineered to

de-emphasize the status of the interviewer/instructor, required the learner to

formúlate specific ESP task objectives. Extensive negotiation of the curriculum

and task-focused activities, as well as frequent exchanges of the roles of expert

and novice, resulted in the development of an ordered list of distinct tasks leading

to the leamer-stated goal (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Summary of tasks, interlocutor roles, and outcomes.

1. Identify business need for English language use.

Roles: learner -> expert interviewer -> novice

RESULT: List of business functions

2. Identify skill área of general interest to learner

3 The term "interviewer" seems more appropriate here than "teacher" due to the frequency with which the

learner played the role of expert.

4 Michigan ELI Listening Comprehension Test form 4, oral/aural score 36/45, reading score 62/80.

204 Revista d e L e n g u a s p a r a Fines Específicos N - 3 (1996)

Task Based Language Teaching in a Leamer-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

Roles: learner -> expert interviewer -> novice

RESULT: Learner goal is to write effective business letters

3. Discourse analysis of skill área

Roles: learner -> expert interviewer -> expert

RESULT: Chart (see Figure 2)

4. Explore American business standards in letter writing

Roles: learner -> novice interviewer -> expert

RESULT: Letter formats tend to repeat themselves with minor

adjustments. Learner goal is to prepare a reference bookof letter

types meeting standard letter-writing needs.

5. Select a target form.

Roles: learner -> expert interviewer -> expert

RESULT: Letter of apology

6. Analyze the complaint process.

Roles: learner -> expert interviewer -> novice

RESULT: Complaint form was generated by learner

7. Assess the politics of business letters.

Roles: learner -> expert interviewer -> expert

RESULT: Surface and deeper needs of customers were

examined in addition to business concerns.

8. Assess the parts of an apology letter.

Roles: learner -> novice interviewer -> expert

RESULT: Four parts of an apology letter were identified->

greeting and acknowledgement, action, compensation, polite

closing.

9. Write examples of each part of an apology letter.

Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N- 3 (1996) 205

Phoenix Lundstrom

Roles: learner -> novice interviewer -> expert

RESULT: Examples were composed.

10. Select exemplars of three registers (acknowledgement, regret,

great concern) for each apology letter type.

Roles: learner -> expert interviewer -> expert

RESULT: Opening and closing paragraphs exemplars were

selected.

11. Perform final grammar checks.

The interviewer met with the learner twice weekly for 14 weeks in

the work place literacy program offices where individual carrels were used for

tutoring purposes. Each session lasted 1.5 hours. Early sessions concentrated

on identifying language use patterns requiring English in the leamer's working

environment; the learner collected English language use data using audio-tapes

and notes. He subsequently took the role of expert when informing the

interviewer. The interviewer asked the learner to clarify and expand on the

Information, which promoted the use of spoken English. A list of functions the

learner had to perform using English was developed:

1. negotiate (service prices and billing procedures with local hotels

and transportation providers)

2. request (services)

3. confirm (reservations)

4. complain (about services)

5. notify (customers of services)

6. apologize (to customers)

7. advertise

8. particípate (in business association functions)

Examination and discussion of the English language use üsts resulted in the leamer

stating his initial goal: the abüity to write clear, accurate and effective business letters.

206 Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N- 3 (1996)

Task Based Language Teaching in a Leamer-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

Standard letter-writing practices in the United States and Japan were

compared. Multi-source samples of letters collected by the leamer, and some

prompting from the interviewer, helped the leamer to discover the following:

1. It is common business practice in the United States, to use form

letters for standardized responses to frequently encountered

situations.

2. Form letters and outlines for less-standard letters which require a

more personal response, are kept on file for use by management

and office staff.

The learner renegotiated his goal; development of a resource notebook of

letters by type and register tailored to meet the needs of his business.

The leamer's first task was to examine letters from his files and from samples

provided by the interviewer to determine what types of Information had been

included in each letter. He then compiled a list of Information types and made

a comparison across letter types (see Figure 2).

Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N° 3 (1996) 207

Phoenix Lundstrom

Figure 2

Discourse analysis of business letter writing needs for English by activity

type and operation required.

Operation

Negotiate Request Confirm Complain Explain Apologize Ad.

Contact Ñame x x x x x x x

Contact Number x x x x x x x

To: Transportation

bus X X X X

limo X X X X

airport shuttle X X X X

car renta] X X X X

airlines X X X X

Hotels X X X X

Restaurants X X X X

Newspapers

Clients X

Re: #/rooms, seats X X X X

rate/price X X X X X

class X X X X

duration X X X X

special services:

diet/menu X X X X

wheel chair X X X X

smoking X X

leis X X X X

sight seeing X X X X

room for disabled X X X X

billing X X X X

origin (point of) X X X

destination X X X

arrival time X X X X

208 Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N- 3 (1996)

Task Based Language Teaching in a Leamer-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

departure time x x x x

Job description x

salary X

hours X

applicant x

qualifications

Discussion of the writing requirements revealed that all the categories except

for the apology letter, could be covered by the use of form letters, a file of

which the learner could develop on bis own. Therefore, he decided the target

discourse to be mastered through the work-place literacy program, would be

the apology letter. The steps toward fulfilling this particular goal would be to

clearly outline the complaint and response process, develop a complain checklist

for use by his staff, train the staff in its use, and draft sample letters for each

type of complaint. The first two steps were completed by the end of this project.

3. Results

3.1 A collection of apology letter openings and closings that reflect three

different registers constituted successful completion of the leamer's second goal.

3.2 Over the course of 4 sessions, the learner and interviewer examined the

customer-initiated cycle that would necessitate the use of an apology letter.

Types of complaints, Japanese and American attitudes toward the presenting

problem in a complaint, affective needs of the client and socio-economic needs

of the learner's business were considered.

3.3The product of these discussions was a complaint checklist to be used by

all members of learner's staff when receiving a complaint cali or letter. The

checklist would make it easier for his staff to gather basic Information from the

customer including an assessment of the customer's affective needs.

Examination of the presenting complaint and the affective needs involved would

facilítate the analysis of the consequences (impact of the complaint on

relationship between the learner's business and the client and between the

learner's business and the service provider if applicable) and a determination of

compensation based on a balance between the seriousness of the precipitating

Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N- 3 (1996) 209

Phoenix Lundstrom

action/event, the impact on the client and the resources of the business. In

addition, the checklist would become a record of the complaint and action taken

as well as a guide for writing the apology letter.

The learner reported that Figure 2 made his "mind clear. I realized that

many facts of things were Unk[ed up]... It was very organized. I learned that

there was [a]way of [considering] surface and deeper [motivations]....! learned

how to analyze letter[s] and when I write [a] letter [I] have to follow (pay attention

to) [the] situation....[I] have learn[ed] a lot of things...I feel very fresh (good)

about [this] way of teaching."

4. Discussion

The success of this instructional design was dependent upon a number of

factors:

1. the specific setting (English for business purposes)

2. the target discourse form (letter writing)

3. the moderately fluent proficiency level and high motivation of the

learner

4. the skill of the interviewer to elicit responses from the learner

5. the ability of the interviewer to guide the process toward work-place

literacy goals

6. the rapport between the interviewer and learner

7. the learner's need for prestige which was fostered through a

negotiation process emphasizing his expert status and the

opportunity to use the English language apology letters with

Japanese clients

Careful attention to each of these points allowed the interviewer and the

learner to form a team, each adopting the roles of expert and novice when

required, each with a clear goal in mind (selected by the learner).

In addition, the instructional process required both the learner and the

interviewer to be flexible so that on-the-spot adaptations to the program could

be made subsequent to the outcome of a negotiative event.

210 Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N - 3 (1996)

Task Based Language Teaching in a Leamer-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

5. Conclusión

If task-based language learning and learner-centered approaches are

considered as means to an end, their complementarity can be readily sean; in

this project what happened was grounded in task-based learning while the way

in which it was carried out reflected the learner-centered approach. The use of

negotiation to perform a needs analysis, inform the curriculum, design and com-

plete target tasks facilitated approaches. A cautious statement can be made

therefore, in support of the use of task-based language teaching techniques in

the learner-centered ESP classroom.

However, the use of only one subject, one setting (small-group), and a limited

domain (apology letters for a service industry business), prohibit the offering of

any broad generalizations about the effectiveness of this technique of instruction

for ESP. Larger studies employing a number of students in small-group settings,

focusing on other ESP target discourse types, and using other types of teaching

personalities are required before the overall effectiveness of combining

learner-centered processes with task-based language learning for ESP can be

assessed. Perhaps this case study might encourage and challenge the reader to

make that future effort.

WORKS CITED

Auerbach, E. 1992. Making Sense, Making Change. Washington, D.C.: Center for Applied

Linguistics.

Auerbach, E. 1993. "PuttingThepBackinParticipatory." TESOLQuarterly,27{i):5A'i-5A5.

Auerbach, E. and Burgess, D. 1989. "The Hidden Curriculum of Survival ESL." TESOL

Quarterly, 190): 475-495.

Bell, R.T. 1981. "Appendix A: Job Analysis and ESP - case study on the canteen assistant" in

R.T. Bell ed., A« Intwduction to Applied Linguistics, Approaches and Methods in Language

Teaching (pp. 159-170). London: Batesford. ed.

Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N° 3 (1996) 211

Phoenix Lundstrom

Center for Applied Linguistics. 1985. "Passage: a journal of refugee education." Passage,

1(1). (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 254 099)

Crookes, G. and Rulon, K. 1985. "Topic and Feedback in NS/NNS Conversation." TESOL

Quarterly, 22(4): 675-6U.

Crookes, G. and Schmidt, R. 1989. "Motivation:Reopening The Research Agenda." University

ofHawaii Working Papers in ESL, 8(1): 217-256.

Delpit, L. D. 1988. " The Silenced Dialogue: Power and Pedagogy in Educating Other People's

Children." Harvard Educational Review, 58(3): 280-298.

Grosse, C. U. 1988a, April. The American Evolution of English for Specific Purposes. Paper

presented at the 7th Annual Eastern Michigan University Conference on Languages for

Business and the professions. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 304

922).

Grosse, C. U. 1988b. "The Case Study Approach to Teaching Business English." English for

Specific Purposes,1{T): 131-36.

Hristova, R. 1990. Video for English for Specific Purposes. Paper presented at the Annual

Meeting of the International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language

(24th, Dublin, Ireland). (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 322 737).

Hutchinson, T. and Waters, A. 1987. English for Specific Purposes: a Learning-Centered

Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johns, A. and Dudley-Evans, T. 1991. "English for Specific Purposes: International in Scope,

Specific in Purpose." TESOL Quarterly, 25(2): 297-314.

Kim, Y. 1992. A Functional-notional Approach for Englishfor Specific Purposes (ESP) Programs.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southwest Educational Research Association.

Houston, Texas.

Krahnke, K. 1987. ApproachestoSyllabusDesignfor Foreign Language Teaching. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kumaravadivelu, B. 1991. "Language Learning Tasks: Teacher Intention and Learner

Interpretation." ELT Journal,45(2): 98-107.

Long, M. H. 1989. Task, Group & Task-group Interaction. University ofHawaii Working Papers

inESL,&(2y. 1-26.

Long, M.H.. "The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition." in W.C.

Ritchie & T.K. Bhatia eds., Handbook of Research on Language Acquisition, Vol. 2: Second

Language Acquisition. New York: Academia Press.

Long, M. H. and Porter, P.A. 1985. "Group Work, Interlanguage Talk, and Second

Language Acquisition." TESOL Quarterly, 19(2): 201-227.

McCormick, L. 1990. "Intervention Processes and Procedures" in L. McCormick & R.L

Schiefelbusch, eds., Language Intervention, An Introduction, pp. 215-260.

New York: Merrill.

Michigan Trade and Industrial Education. 1984. Architectural Drafting Curriculum Guide.

Lansing, Mich.:Michigan State Department of Education, Vocational-Technical Service. (ERIC

Document Reproduction Service No. ED 242 901).

Mohán, B. A. 1990. LEP Students and The Integration of Language and Contení: Knowledge

Structures and Tasks. Office of Bilingual Education and minority language affairs.

212 Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N° 3 (1996)

Task Based Language Teaching in a Leamer-Centered ESP Setting: A Case Study

Washington, DC. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 341 264).

Nobuyoshi, J. and EUis, R. 1993. "Focused Communication Tasks and Second

LanguageAcquisition." ELT Journal, 47(3): 203-210.

Nunan, D. 1993. " Task-based Syllabus Design: Selecting, Grading and Sequencing Tasks" in

G. Crookes & S.M. Gass eds. Tasks in a Pedagogical Context (55-68). Clevedon: Multilingual

Matters Ltd.

Pica, T. 1989. "Classroom Interaction, Negotiation and ComprehensioniRedefining Relations

hips." Papers in Applied Linguistics, University of Alabama, 7(1): 7-35.

Prince, D. 1984. "Workplace English: Approach and Analysis. "Englishfor Specific Purposes,

3:109-116.

Robinson, P. 1980. ESP: The Present Position. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Schmidt, M.F. 1981. "Needs Assessment in English for Specific Purposes: The Case Study" in

L. Selinker, E. Tarone, and V. Hanzeli eds. English for academic and technical purposes.

Rowley: Newbury House.pp.199-210

Schmidt, R. 1992. "Psychological Mechanisms Underlying Second Language Fluency." SSLA,

14: 357-385.

Swaies, J. 1990. "The Concept of Task" in J.M. Swales ed. Genre Analysis. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, pp. 68-82.

Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos N° 3 (1996) 213

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Task Based Learning and Competency BasedDocument17 pagesTask Based Learning and Competency Basedmeymirah100% (1)

- Key Issues in ESP Curriculum DesignDocument3 pagesKey Issues in ESP Curriculum Designintan melati100% (3)

- ESP COURSE DESIGN KLP 6 PDFDocument18 pagesESP COURSE DESIGN KLP 6 PDFM Wahyu RPas encore d'évaluation

- Theoretical Background and Literature ReviewDocument23 pagesTheoretical Background and Literature Reviewgede sudanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Task ESP Delfia Magdalena (2001030072)Document9 pagesFinal Task ESP Delfia Magdalena (2001030072)NandafbrianPas encore d'évaluation

- ELTJ Revised R4Document11 pagesELTJ Revised R4mengying zhangPas encore d'évaluation

- Adminjurnal Improving Students Speaking Proficiency by Using Speaking Board Games For Elementary Students at Eduprana Language CourseDocument12 pagesAdminjurnal Improving Students Speaking Proficiency by Using Speaking Board Games For Elementary Students at Eduprana Language Coursebelacheweshetu222Pas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring Variables of Hospitality and Tourism Students' English Communicative Ability in Taiwan: An Structural Equation Modeling ApproachDocument13 pagesExploring Variables of Hospitality and Tourism Students' English Communicative Ability in Taiwan: An Structural Equation Modeling Approachaamir.saeedPas encore d'évaluation

- Paper ESP Group 4 - TBI 4B (1) OkDocument16 pagesPaper ESP Group 4 - TBI 4B (1) OkMuhammad ulul IlmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter3 4 5Document5 pagesChapter3 4 5PRINCESS AREVALOPas encore d'évaluation

- Task Based Language Learning - Mazaya Khofifah R (1980002)Document16 pagesTask Based Language Learning - Mazaya Khofifah R (1980002)Endang UtudPas encore d'évaluation

- Task-Based Background AssignmentDocument11 pagesTask-Based Background Assignmentpandreop50% (2)

- Effectively Implementing A Collaborative Task-Based Syllabus (CTBA) in EFL Large-Sized Business English ClassesDocument14 pagesEffectively Implementing A Collaborative Task-Based Syllabus (CTBA) in EFL Large-Sized Business English ClassesRina WatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 Esp Approach Not Product and Course DesignDocument3 pagesChapter 3 Esp Approach Not Product and Course DesignK wongPas encore d'évaluation

- EspDocument3 pagesEspNuriPas encore d'évaluation

- Ped Gram Final OutputDocument8 pagesPed Gram Final Outputamara de guzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Power Point of ESPDocument12 pagesPower Point of ESPSelvi ZebuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Work For Teaching English For Esp Learners.: Pham Duc ThuanDocument16 pagesProject Work For Teaching English For Esp Learners.: Pham Duc ThuanRodica Stanislav CiopragaPas encore d'évaluation

- Esp Assignment FinalDocument15 pagesEsp Assignment Finalapi-262885411Pas encore d'évaluation

- Task Based LearningDocument9 pagesTask Based LearningjaeagmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 3 SlidesDocument2 pagesLecture 3 SlidesAbdullah Hassan Bilal ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- ESP Teaching and LearningDocument13 pagesESP Teaching and LearningLan Anh TạPas encore d'évaluation

- UJIAN TENGAH SEMESTER ESP COURSE DESIGN Oktober 2023Document8 pagesUJIAN TENGAH SEMESTER ESP COURSE DESIGN Oktober 2023Reza FahleviPas encore d'évaluation

- My ReportDocument14 pagesMy Reportzafra.elcanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Task - Based Language TeachingDocument17 pagesTask - Based Language TeachingPatricia E MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- Imanul Buqhariah 1505112575: Implementing Task-Based Language Teaching (David Beglar and Alan Hunt)Document7 pagesImanul Buqhariah 1505112575: Implementing Task-Based Language Teaching (David Beglar and Alan Hunt)Imam BuqhariPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Planning and Syllabus DesignDocument28 pagesCourse Planning and Syllabus DesignMd. Al-aminPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Designing Material For Teaching English Full PaperDocument14 pagesFinal Designing Material For Teaching English Full Paperjelena pralasPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Learners' and Teachers' Perceptions of Task RepetitionDocument11 pagesLanguage Learners' and Teachers' Perceptions of Task RepetitionMaría Alessandra Griffin SánchezPas encore d'évaluation

- 2963-Article Text-7476-1-10-20190902Document13 pages2963-Article Text-7476-1-10-20190902Jinny GabriellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introducing The ER Course - Revision - Dec17Document12 pagesIntroducing The ER Course - Revision - Dec17Linh Lại Thị MỹPas encore d'évaluation

- Task Based LearningDocument4 pagesTask Based LearningBambang SasonoPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of ESPDocument2 pagesDefinition of ESPAlya Kayca0% (1)

- Task Based LearningDocument6 pagesTask Based LearningJossy Liz García PeñaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Use of Task-Based Learning To Develop English Speaking Ability of Mattayomsuksa 4 StudentsDocument30 pagesThe Use of Task-Based Learning To Develop English Speaking Ability of Mattayomsuksa 4 StudentsEliana Patricia Zuñiga AriasPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment of English For Specific Purposes (ESP)Document12 pagesAssignment of English For Specific Purposes (ESP)FauzieRomadhonPas encore d'évaluation

- English For Academic Purposes: English For General Skills Writing CourseDocument24 pagesEnglish For Academic Purposes: English For General Skills Writing CourseTamer El DeebPas encore d'évaluation

- Needs Analysis IntroDocument3 pagesNeeds Analysis IntroBen AyşePas encore d'évaluation

- Development of ESPDocument7 pagesDevelopment of ESPLeah Mae BulosanPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of ESPDocument7 pagesDevelopment of ESPLeah Mae BulosanPas encore d'évaluation

- 224 425 1 SMDocument8 pages224 425 1 SMfebbyPas encore d'évaluation

- Using A Jigsaw Task To Develop Japanese Learners' Oral Communicative Skills: A Teachers' and Students' PerspectiveDocument17 pagesUsing A Jigsaw Task To Develop Japanese Learners' Oral Communicative Skills: A Teachers' and Students' PerspectiveMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemPas encore d'évaluation

- Problems in Teaching English For Specific Purposes (Esp) in Higher EducationDocument11 pagesProblems in Teaching English For Specific Purposes (Esp) in Higher EducationHasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Esp ReviewerDocument6 pagesEsp ReviewerAltea Kyle CortezPas encore d'évaluation

- Training-Programme English LanguageDocument5 pagesTraining-Programme English LanguageAtaTahirPas encore d'évaluation

- Task-Based English Language Teaching .Bibha DeviDocument21 pagesTask-Based English Language Teaching .Bibha DeviBD100% (1)

- Needs Analysis - A Prior Step To ESP Course DesignDocument29 pagesNeeds Analysis - A Prior Step To ESP Course DesignAmm Ãr100% (1)

- Designing Esp CoursesDocument10 pagesDesigning Esp CoursesTirta WahyudiPas encore d'évaluation

- ESP General English (GE)Document3 pagesESP General English (GE)Eka AmaliaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Strengths and Weaknesses of Task Based Learning (TBL) Approach.Document12 pagesThe Strengths and Weaknesses of Task Based Learning (TBL) Approach.Anonymous CwJeBCAXpPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter IiDocument31 pagesChapter IiismiPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is EAPDocument9 pagesWhat Is EAPMoyano Martin 8 6 6 5 5 9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Book Effective Teaching and Learning English For Spesific PURPOSE - PDFDocument117 pagesBook Effective Teaching and Learning English For Spesific PURPOSE - PDFAbdulghafur HadengPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - Tecniques and Principales in Language Teaching PDFDocument34 pages1 - Tecniques and Principales in Language Teaching PDFtutuPas encore d'évaluation

- Esp English For Specific PurposesDocument57 pagesEsp English For Specific PurposesMæbēTh CuarterosPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Implementing Recitation Activities On Success Rates in Speaking Skills of Grade 12 Gas in Genesis Colleges IncDocument6 pagesEffects of Implementing Recitation Activities On Success Rates in Speaking Skills of Grade 12 Gas in Genesis Colleges IncAngeline AlvarezPas encore d'évaluation

- Am BarDocument2 pagesAm BarKang Mas HarryPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of ESP:: Absolute CharacteristicsDocument2 pagesDefinition of ESP:: Absolute Characteristicszohra LahoualPas encore d'évaluation

- DCS Seam 3Document25 pagesDCS Seam 3tony ogbinarPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020 Specimen Paper 1 Mark SchemeDocument2 pages2020 Specimen Paper 1 Mark SchemeMohammed ZakeePas encore d'évaluation

- Demo K-12 Math Using 4a's Diameter of CircleDocument4 pagesDemo K-12 Math Using 4a's Diameter of CircleMichelle Alejo CortezPas encore d'évaluation

- TN Board Class 11 Basic Electrical Engineering TextbookDocument256 pagesTN Board Class 11 Basic Electrical Engineering TextbookJio TrickzonePas encore d'évaluation

- 6min English Team BuildingDocument5 pages6min English Team BuildingReza ShirmarzPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction - The Role of Business Research (19.01.10)Document27 pagesIntroduction - The Role of Business Research (19.01.10)sehaj01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Igwilo Edel-Quinn Chizoba: Career ObjectivesDocument3 pagesIgwilo Edel-Quinn Chizoba: Career ObjectivesIfeanyi Celestine Ekenobi IfecotravelagencyPas encore d'évaluation

- My Favorite Meal EssayDocument7 pagesMy Favorite Meal Essayb71g37ac100% (2)

- Incorporating Music Videos in Theory CoursesDocument5 pagesIncorporating Music Videos in Theory Coursesapi-246372446Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Natural Approach To Second Language Acquisition PDFDocument14 pagesA Natural Approach To Second Language Acquisition PDFchaitali choudhuryPas encore d'évaluation

- Pongsa.P@Chula - Ac.Th: MSC in Logistic Management, Chulalongkorn University Page 1 of 2Document2 pagesPongsa.P@Chula - Ac.Th: MSC in Logistic Management, Chulalongkorn University Page 1 of 2Bashir AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- College Wise Pass PercentageDocument6 pagesCollege Wise Pass PercentageShanawar BasraPas encore d'évaluation

- 102322641, Amanda Wetherall, EDU10024Document7 pages102322641, Amanda Wetherall, EDU10024Amanda100% (1)

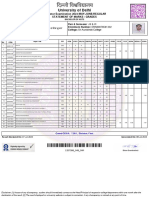

- University of Delhi: Semester Examination 2023-MAY-JUNE:REGULAR Statement of Marks / GradesDocument2 pagesUniversity of Delhi: Semester Examination 2023-MAY-JUNE:REGULAR Statement of Marks / GradesFit CollegePas encore d'évaluation

- Innovative Technologies For Assessment Tasks in Teaching andDocument31 pagesInnovative Technologies For Assessment Tasks in Teaching andRexson Dela Cruz Taguba100% (3)

- Auburn Core CurriculumDocument1 pageAuburn Core CurriculumLuisPadillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Heather Martin Art Resume 2019Document2 pagesHeather Martin Art Resume 2019api-359491061Pas encore d'évaluation

- Statement of PurposeDocument2 pagesStatement of PurposeAnil Srinivas100% (1)

- GIC Assistant Manager Post (Scale-I) 2022: Exam Pattern, Tricks, Syllabus & MoreDocument9 pagesGIC Assistant Manager Post (Scale-I) 2022: Exam Pattern, Tricks, Syllabus & MoreShatakshi SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- 1842 13404 1 SMDocument7 pages1842 13404 1 SMnanda wildaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bbfa4034 Accounting Theory & Practice 1: MAIN SOURCE of Reference - Coursework Test + Final ExamDocument12 pagesBbfa4034 Accounting Theory & Practice 1: MAIN SOURCE of Reference - Coursework Test + Final ExamCHONG JIA WEN CARMENPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid-Term Assignment - Sun SimaDocument2 pagesMid-Term Assignment - Sun SimaSima SunPas encore d'évaluation

- ST3 - Math 5 - Q4Document3 pagesST3 - Math 5 - Q4Maria Angeline Delos SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Coaching Islamic Culture 2017chapter1Document8 pagesCoaching Islamic Culture 2017chapter1FilipPas encore d'évaluation

- Thaarinisudhakaran (4 3)Document1 pageThaarinisudhakaran (4 3)vineeth rockstar1999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mode of VerificationDocument15 pagesMode of VerificationVincent LibreaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 AL GIT Marking Scheme English Medium PDFDocument24 pages2016 AL GIT Marking Scheme English Medium PDFNathaneal MeththanandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Deca Full Proposal SchemeDocument3 pagesDeca Full Proposal SchemeAanuOluwapo EgberongbePas encore d'évaluation

- Lab 1 - Intro To Comp ProgramsDocument11 pagesLab 1 - Intro To Comp Programssyahira NurwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Elizabeth Malin EDLD 5315 Literature ReviewDocument24 pagesElizabeth Malin EDLD 5315 Literature ReviewebbyfuentesPas encore d'évaluation