Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

SCAMS & SCAMMERs AGENTS & International Office

Transféré par

darwiszaidiCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SCAMS & SCAMMERs AGENTS & International Office

Transféré par

darwiszaidiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SCAMS & SCAMMERS: AGENTS AND THE

INTERNATIONAL OFFICE

A CAUTIONARY TALE

Virginia Pattingale

Flinders University

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to address an aspect of risk in international education – the

relationship between agent and provider. In addition to the literature, the paper draws on

anecdotal evidence to illustrate an issue that is seldom discussed. The paper addresses

three themes: commercial integrity, ethical behavior and, risk management in

commercial relationships.

For clarity, the discussion is categorised into:

- Scams and Scammers - a sweep of the territory

- Relationships between higher education institutions and the international

education recruitment agent network

- Risk analysis and management of the agent relationship in higher

education

- Case studies

- Integrity issues in higher education generally

- Some ideas for improving integrity in those commercial partnerships.

“Among the important roles of any public sector agency is the maintenance of high

standards of ethics, conduct and fiduciary responsibility. Having a clear overall policy will

demonstrate the agency’s resolve to combat fraud and corruption wherever it is found. It

will communicate the agency’s commitment to best practice and create a holistic

framework that minimises the risks of fraud and corruption and strengthens

organisational integrity.”

(Crime and Misconduct Commission 2005, p. 2)

Universities have established processes for risk analysis and identification of fraudulent

activities. They have developed systems around examinations and assessment to

ensure integrity of students’ work. There is awareness of the issues of degree mills,

accreditation mills, plagiarism, etc. NOOSR and UK NARIC provide publications and

training for staff whose role it is to assess and verify foreign documentation for

admission into universities. As universities have become more commercially oriented,

fraud has become more prevalent. Much has been written about academic and identity

fraud in the sector but as we enter into new forms of commercial activity we encounter

new forms of fraud.

The focus here is not on student or academic fraud, but on business to business fraud

relating to the relationship between the agent and the provider. The Education Services

for Overseas Students Act 2000 together with the National Code of Practice for

Registration Authorities and Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students

(as amended 2007) (The National Code) are the key components in maintaining the

Australian International Education Conference 2007 1

www.idp.com/aiec

quality and integrity of the international education industry in Australia. Standard 4 of

The National Code addresses the management of the agent relationship and identifies

that the provider must have a written agreement with an education agent if they formally

represent it, and compliance with the National Code must be spelt out in that agreement.

It also stresses that the institution must have processes for monitoring the activities of

the agents, where corrective actions and termination conditions might be required.. The

responsibility placed on institutions to adequately select, monitor and terminate these

relationships is a requirement not an option.

“Fraud in higher education is a complex matter, which by definition eludes

comprehensive data and straightforward recommendations. As mass higher education

develops across the world, and provision is increasingly commercial, international and

IT-enabled, fraud may only be expected to increase in scale, sophistication and

significance.” (Garrett, R 2005, p. 1)

The business relationship between education providers and international student

recruitment agents in Australia is confidential. This paper is based on an analysis of

publicly available information from websites, press coverage, documents and includes

some anecdotal evidence. This is not an exhaustive account of corruption and fraud in

the higher education sector, rather it touches on issues and experiences with a view to

raising awareness and developing strategies to counter the problem. Dealing with scams

and fraud in higher education is about managing risk and developing a culture of

integrity that includes the provider and its partners.

Scams and Scammers a sweep of the territory

Are scams illegal? Some do involve unlawful conduct. They are generally created by

devious and resourceful people. Fraudsters are hard to prosecute. Fraud is difficult to

stamp out and if you have become a victim, recouping your money is improbable. The

scale of the problem is highlighted by websites where scams were exposed, such as

hoaxslayer and fraudwatch international.

Scams include phishing – a form of identity theft where a fraudster pretends to be a

legitimate organisation requesting personal and financial details. This has become so

sophisticated that its victims include financial institutions. Scammers don’t just want

money, they are after identities. Personal details are more valuable than money as it is

possible to commit further identity fraud using these identities. More commonly known

are the ubiquitous “Nigerian” scams, where an unsolicited request for money comes with

a promise of a ‘cut’ of vast sums, sometimes millions, that are tied up in overseas bank

accounts. The victim assists by providing ‘advances’ to smooth the way for the funds

release. The only real money is that which the victim sends as the advance, and

generally that will be the last they will see of it. There are myriad investment frauds and

business opportunity scams, dating scams, multi-level marketing, tax fraud schemes, the

charity hoax, the student scholarship hoax, etc.

Some of the most fantastic are the false nation’s scams. The Principality of New Utopia

founded by Oklahoman, Howard Turney (aka His Highness Prince Lazarus). This is, in

fact, a number of abandoned Gulf of Mexico oil platforms lashed together over a reef in

the Caribbean. It claims to have a University with a Medical School specialising in

research into longevity. Prince Lazarus has had a long connection with longevity drug

Australian International Education Conference 2007 2

www.idp.com/aiec

scams. Often they exist only in cyberspace to sell worthless company and business

registrations, bank licences and ‘citizenship’ to gullible victims.

The lesson is, don’t believe everything you read and if it looks too good to be true it

probably is. One of the main tips from a lengthy list, available at

www.scamwatch.gov.au. is to use your common sense. But if it is simply a matter of

‘common sense’, why do scams succeed?

“Firstly, a scam looks like the real thing,” and “Secondly, scammers manipulate you by

‘pushing your buttons’ to produce the response they want. It’s nothing to do with you

personally; it’s to do with the way individuals in society are wired up emotionally and

socially.” (www.scamwatch.gov.au 2007)

It is said that our best response to scams is not to respond, don’t answer, delete it,

destroy it, hang up.

Relationships between higher education institutions and the international

education recruitment agent network

Universities work in a global market and the agent network provides a valuable service

in this context. Few universities have the human, capital and time resources to operate

effectively in multiple markets. Agents work alongside websites, brochures, academics

and international office staff in marketing institutions. Agents follow up, promote in

market, host visits, counsel potential students and represent universities in a legitimate

and legally binding relationship.

These partnerships are usually with privately owned business, ranging in size from

single individuals to large networked agencies acting in multiple countries for multiple

institutions. Some have networks and sub-agency arrangements stretching the capacity

of single institutions to monitor, review, reward or expose agents. We see the outcome

of students arriving in Australia, but how much do we know about the route they took to

get here? What do we know about their encounter with our partner and service provider?

Did the agent charge the student $2,000 to put in an application? Did they correctly

advise about the amount of English language study the student would need to meet the

entry requirements into the course? Did they steer the student away from a course at

one University because another University pays a higher commission?

The Australian government makes universities, and other educational institutions,

responsible for ensuring that agents, preserve our reputation as quality institutions with

high standards of ethical behaviour and trustworthiness. The institution is vulnerable by

its reliance on agents. Due diligence, regular review, constant communication and at

times censoring action must be part of this relationship. This is a significant business to

business relationship and there is a great deal at stake.

In her article titled Foreign students don't come cheap, Milanda Rout claims that

“Universities are spending more than $64 million a year paying offshore agents

commission to recruit international students as the battle for the overseas market

intensifies.” (Rout 2007, p. 23)

The interconnection between skilled migration and international education should not be

underestimated. The commercial nature of both is a driver for cross-selling with many

education agents also acting as migration agents and vice versa. Universities and

Australian International Education Conference 2007 3

www.idp.com/aiec

agents are aware that demand for certain courses of study has resulted in ‘product’

development for specific migration markets. This raises questions, about ‘selling’

graduate outcomes, notably, achieving employment in the ‘skilled migration professions’.

It is in the interest of the education sector in Australia to preserve the reputation of

‘Brand Australia’. I advocate sharing information between institutions, communicating

about best and worst practice. Networks such as the Australian International Directors

Forum (AUIDF) have the potential to share and act on this information, but there is

natural hesitancy to act as the industry’s watchdog and whistleblowers. We recognise

academic fraud as a pervasive negative influence in the industry but other unethical

behaviour associated with international student recruitment could have serious effects

on the credibility and trustworthiness of institutions, their products, services and

outcomes.

“The ‘buying of academic success’ can in fact constitute a strong disincentive for

students to learn and cast doubt on the quality of diploma and degree holders; the

selling of ‘university seats’ can damage the reputation of academia as a whole;

plagiarism or the manipulations of research results can harm the development of the

academic corpus; and more globally speaking, academic fraud can endanger the

credibility and usefulness of the assessment systems in place and the value of academic

degrees, promoting distrust about the academic enterprise at large. Moreover, it can put

at risk the education export industry, which has become a major business in countries

such as Australia. Unfortunately, public authorities often feel powerless to address these

acute problems.” (Hallak & Poisson 2007, p. 234)

Risk analysis and management in higher education

“Risk management is an integral part of good management practice. It is not an ‘optional

extra’, to be considered in isolation. It should permeate the agency’s activities as an

operational philosophy.”

(Fraud and Corruption Control, Guidelines for Best Practice 2005, p. 12)

According to this document these are the following steps that should be taken in a risk

management approach:

- Identifying risk

- Analysing risk – using qualitative risk, management matrix – significance,

likelihood and frequency of risk

- Evaluating risk

- Treating the risk

- Monitoring the process via regular evaluation

- Communicating and consulting with stakeholders

- Recording the outcomes

- Implementing the risk management approach eg. a risk management

committee and plan

- Developing a fraud and corruption management policy.

Marcus Turner, of the NSW Department of Commerce, investigates the link between

reputation risk management and corporate governance. He asserts that it is possible to

turn this issue into an advantage by leveraging risk management for a reputational edge.

Australian International Education Conference 2007 4

www.idp.com/aiec

He argues that a robust risk management program engaging all stakeholders can

influence the achievement of organisational objectives and will develop the organisation

the reputation of being at the top of it’s game. Conversely, not having a transparent risk

management strategy to protect the organisation’s reputation can prove reckless. There

is a reputation risk to an institution which fails to protect its logo and testamurs from

illegal use. Imagine if this story below were to arise out of an internet generated ‘hoax’

using a real university’s logo, Vice Chancellor’s signature, university seal, etc. A bit of

downloading and an understanding of Photoshop can generate potentially disastrous

results on the image and reputation of an institution. Even though the university is fake,

the story made international news and this case detracts from the validity of gaining a

university degree.

“In another case two American men conducted a fraudulent university, ‘Trinity Southern

University’. In a sting operation, officials from the Pennsylvania Attorney-General’s Office

paid US$398 for an MBA Degree which was awarded to a cat called ‘Colby’, including a

transcript of results which indicated that the cat had earned a 3.5 grade point average

(The Commercial Appeal 2004, ‘MBA for cat busts fake degree sales’, 11 December:

A5)” in (Smith 2005 p. 4)

Case Studies

Most agents are honest and have the interests of the students and partners in mind.

There are rogue agents who have behaved unscrupulously including those who charge

forward fees to students who are then unable to leave that agency, because their money

is locked in. Or those who tell students they will only need five weeks of English, when

they really need more than 30 weeks. International office colleagues have shared case

studies from their own experiences of fraud in the workplace revealing just a taste of the

range of activities confronting the industry. These gaps in integrity are not only found

among agents and students, but also among staff.

International Draft Scam. A prospective international student approached a University

to enrol as a student. An international draft for tuition fees was forwarded, payable to the

University. The draft was banked. A number of days later the international student

contacted the University advising that due to a family tragedy they would no longer be

able to attend the University and consequently requested a refund of the fees already

paid (the figure was close to $10,000). The revenue staff became suspicious and looked

into the request. Meanwhile the bank contacted the University to advise that the draft

had been dishonoured and appeared to be fraudulent. Clearly the intent was to have

received the refund prior to the University being notified of the fraudulent draft.

Web Scams. An agent in country Y involving University X where the agent set up a

website with the following URL. http://www.universityX.countryY.com

The website linked directly to the agent’s own website. Suddenly the other agents in

country Y started to complain because it looked like this was the ‘official website of

University X’ directing the enquiries straight to the agent. The other agents assumed that

the agent was getting preferential treatment but in fact he had simply purchased the URL

and used it for his own purpose. There is nothing illegal in his action. It does, however,

compromise University X who went to great lengths to ensure that the agent change the

website and stop using the University name in the URL. The agent complied and they

are still partners.

Australian International Education Conference 2007 5

www.idp.com/aiec

Another agent set up a website using information and logos of multiple Universities

creating the impression that this agent represents these institutions. None of the

Universities have a formal relationship with this agent. Because the agent is not an

authentic agent, there is little the Universities can do about the problem. It has proven

difficult to protect the logos from being downloaded, or used in electronic forms.

Misrepresentation Scam. The case of the University who found one of their agents

complaining to them about their apparent visit to his province in China. He complained

they were advertising interview sessions to students and had not consulted him about

the new agency they were working with. The advertisements claimed that

representatives from the University would be there to discuss courses and take

applications (and application fees, no doubt). Further investigation found that a local

company, not an agent of the University, was indeed advertising these sessions in local

newspapers, using the University logo downloaded from the internet and hiring Russians

to act as Australian counselling staff.

An agent sent a student to the University. The student enrolled in a BA, but was puzzled

that none of the topics included fashion design. The student explicitly wanted to study

fashion design and was told by the agent that a BA at this University was a great fashion

course. The University helped the student into another university and paid the airfare to

get him there.

Double Dipping Scam. An agent is accused of double dipping on commissions. He sent

a second invoice for the same student, in the same course. The University had a system

of paying on invoices for multiple students with a grand total. They did not have a clear

way of recording against the students name what was paid and when. The second

commissions were paid. The agent did it accidentally in the first instance but when it

wasn’t discovered they tried again successfully and then, of course, it became a

lucrative habit. It was exacerbated by the fact that sometimes the invoices would arrive

months after the student had commenced and the University was not good at tracking its

payments over time. A response to this was to set up a new system of a unique invoice

number for each student. This has resolved the problem. The University was also

concerned that perhaps one of the staff who had sole responsibility for paying

commissions may have been working by prior arrangement with the agent. An audit by

an outside consultant identified that a key risk to the University was having a single

person responsible for this commission payment task.

Conflict of Interest. A University’s marketing staff person asked permission to sign up a

close relative as an agent. At no stage did they alert the University that the agent was

related to them even though the agent was operating in their marketing region and there

was a conflict of interest. The scam was discovered but the staff person claimed to be

innocent of all knowledge of how this could have happened and spun a range of

increasingly unbelievable stories around the matter, consistently denying a conspiracy.

Only after extensive investigation and confrontation, involving the University’s Human

Resources section, the Unions and provision of irrefutable written evidence did the staff

person accept that there was something untoward. At this point, even though the saga

had drawn out over two months, the staff person’s last resort was to claim that the

relative had misled them and that they were shocked and appalled. The staff person was

married to the agent and lived with them at the business address.

Australian International Education Conference 2007 6

www.idp.com/aiec

Theft. The Agent who takes a non-refundable upfront payment from all students for the

services that the universities provide free, eg. airport pickup, orientation and

accommodation support.

The implication of these few examples is that fraud takes many forms and evolves over

time. Discovery by one institution could be shared to assist others in avoiding the same

pitfalls.

Integrity issues in higher education

Much has been written about academic fraud and the forms it takes and solutions to it.

There are experts in the field of degree mills and identity theft. There are techniques for

identifying fraudulent documents but they are barely keeping up with technological

developments to create them. The resourcefulness and determination of those who want

to scam the system means that degree mills and accreditation mills are a growing

phenomenon.

Hallak and Poisson identify the following as examples of the types of fraud and

corruption opportunities within the higher education industry. Degree mills, exam

scandals, fake degrees, institutionalised cheating, plagiarism, expensive tutorials as

prerequisites for entry or success, leakage of examination papers, nepotism, bribery,

impersonation, smuggling foreign information into exams, cellular phone assistance,

collusion among candidates, intimidation by supervisors, purchase of papers over

internet, admissions fraud, scoring malpractice, bribery of academic authorities,

falsification of results, illegal changing of rankings on admissions lists, sale of seats, fake

credentials, manipulation of CVs and fabrication or falsification of research results and

data, to name just a few.

Garrett makes a point that as higher education institutions worldwide receive less

income from the state, competitive pressures may encourage admissions abuse and, by

extrapolation, other types of behaviour that may be considered to be unethical, to

secure funds.

“An important aspect of ‘borderless’ higher education is the increasing commercial

interest in post–secondary education as a business and a market. Not only has the

volume of commercial activity grown in recent years, but the range has widened and cut

across what might be called the ‘core business’ of non-profit higher education teaching

and learning. What was missing was a substantive attempt to assess the significance of

different business models and gauge the balance of competitive and service

relationships”. (Garrett 2004, p. 11)

So why do students want false documents that they know give them credentials they

have not earned? It is often an economic decision. Drivers include, competition for jobs

and professional appointments, the globalisation of the education and the labour market,

and the difficulty in verification of foreign credentials. Advances in new technologies,

including the internet enable fraud in new ways. It is hard to catch scammers, theirs is a

commercial imperative too.

“If these are counterfeited or altered, they can form part of a chain of documents used to

perpetrate a wide range of financial crimes, false student identity cards can be used (in

Australian International Education Conference 2007 7

www.idp.com/aiec

conjunction with other documents) to obtain birth certificates, drivers’ licences, passports

and then to open bank accounts.” (Smith 2005 p. 2)

Academic fraud can include the use of false documents leading to even worse criminal

activity. Tracking and identifying academic fraud is in the public interest and identity

fraud is a particular concern. You can buy a fake degree from even the most reputable

institutions such as Harvard and Yale. These fake degrees are often sold as ‘joke

degrees’ but they can be used for purposes that escalate into higher order criminal

activity. Universityies use text-matching software eg. SafeAssignment as a detection and

educative tool and provide a clearly articulated policy on the internet. Universities

subscribe to NOOSR and UK NARIC for identifying documents and qualifications that

verify foreign credentials. These provide training courses for admissions staff on

detection of fraudulent documents. In Degrees of Deception, UK NARIC assert, that

fraudulent documents are not new but over the past 15 years it has become a worldwide

problem. The trade is now global and security measures are inadequate to curb it. The

increased commercial value of academic qualifications, eg.credentialism is a major

driver. Fake degrees are highly marketable.

Some ideas for improving integrity in those commercial partnerships

The “virtuous triangle” construct (Hallak & Poisson) for improved transparency and

accountability are reflected by the axes described below:

- Creation and maintenance of regulatory systems

- Strengthening of management capacities

- Enhanced ownership of the management process.

“The triangle should include a learning environment that values integrity, well designed

governance with effective, transparent and accountable management, and a proper

system of social control of the way the sector operates and consumes resources.”

(Hallak & Poisson 2007, p. 25)

I have taken some of the ideas that Hallak and Poisson developed for good practice in

dealing with academic fraud and applied them to managing the agent relationship. Some

of these ideas incorporate what we, in universities, already do and some that we should

consider doing.

- Adherence to The National Code particularly in the appointment,

monitoring and review of agents.

- Develop policy that clearly stipulates what is tolerable and what is not.

- Increase measures to detect fraud – mystery shopper students,

questionnaires for students about agent performance, fees charged, and

services delivered.

- Integrity regularly assessed –look at conversions, applications. If agents

are charging application fees to students with low conversion rates – take

action.

- User friendly information on recruitment procedures – make it clear to

students what they should expect from our agents – make it clear what

they should NOT expect.

- Rewarding agents for best practice, productivity and integrity and greater

acknowledgement of ethical agents.

Australian International Education Conference 2007 8

www.idp.com/aiec

- Industry sharing of information about unethical agents and strategies for

ensuring good practice.

- Agent training.

- Accrediting agents in a similar way as Migration Agents are accredited

and public notification of agents that are de-registered like migration

agents.

These ideas, rewards and penalties, reinforcement of regulatory systems, using

computerised systems, external audits, engagement of our stakeholders and staff in the

development and implementation of policy and processes resonate with our universities.

The complexity and multiple manifestations of poor practice can be addressed by

focussing on certain elements of the commercial relationship between the institutions

and the agent relationship. A priority for international offices is to develop guidelines and

policy around this territory.

How widespread is this problem? Is a coordinated approach of interest? Should action

be taken at the political level? In March and April of 2007, the 7.30 Report investigated

the “trade in international students” and screened a three part series on the subject

(excerpt below). The issue of accreditation for the education agents was raised. It was

pointed out that anyone can hang up a shingle to become an education agent and that

the industry has sought a national register of education agents. The government’s

position is clear.

HEATHER EWART: For the past 18 months university vice-chancellors, TAFE colleges

and the peak body representing private operators have been lobbying the Federal

Government for rules and regulations to stamp out rogue education agents. At the

moment, the Government puts the onus on university and college operators to ensure

their agents are doing the right thing and has no intention of changing this approach.

JULIE BISHOP, EDUCATION MINISTER: Because the vast majority of them are located

overseas, Australian laws don't cover them, so what we do is regulate the providers. We

make the providers responsible for the acts of the agents.

By contrast, in Australia, The Register of Migration Agents, lists registered individuals

(not organisations) who are the only people authorised to provide immigration assistance

except where exemptions are provided for. This is a public record. The Authority is

required to publish decisions in relations to agents who have been cautioned, cancelled,

suspended or barred. All registered migration agents must meet qualification

requirements for registration, be of good character and abide by the Migration Agents

Code of Conduct. The code encapsulates many of the ethical principals that we would

ask of our education agents. Principals, including informing clients of their fee structure

and holding in the clients account, money paid by the client until the services are

completed. There is a section on complaints and a procedure for dealing with them and

a section on termination of services. Education agents in Australia and offshore have no

such Code of Conduct or even a register of agents. Each institution has its own

selection, monitoring and review procedures and each has their own agreement, setting

out the roles and responsibilities of the parties. Is this enough?

Is training or self-regulation the solution? Parents and students trust the agents to deliver

a service as most of them have little experience of what to expect or do. The agent’s

reputation is just as important to their business as it is to ours. Those who do the wrong

Australian International Education Conference 2007 9

www.idp.com/aiec

thing can ruin their own reputation and influence the reputation of the institutions they

represent and the industry as a whole. The students may not be aware that what the

agent is acting dishonestly or that the level of service provided is not commensurate with

the money paid, but word of mouth spreads quickly. All partners need to embrace an

ethical approach in the supply chain and act scrupulously.

Professional International Education Resources (PIER) provides the Education Agent

Training Course (EATC). Student counsellors and agents can undertake the training,

free online. The industry acknowledges this valuable resource and some encourage their

international office staff to undertake it. The training incorporates:

- Australia, the AQF and Career Trends

- Legislation and Regulations

- Working effectively in International Education

- Professional Standards and Ethics.

The ethics module is salient to this discussion. Examples are provided of unethical

practice in dealings with students, institutions and with the education industry. An

agent/counsellor gains a statement of attainment by successfully completing an

assessment. They are then listed as “Qualified Educational Agents/Counsellors” on the

PIER website. They can, under certain circumstances, become de-listed. Paula

Dunstan, (PIER) Manager said that, “Institutions and students alike can view this list and

see if their agents are listed. This is as close as anyone has come to regulating the

agents”.

Another approach to the development of skilled and ethical agents is the Association of

Australian Education Representatives in India (AAERI). Formed in 1996, their goal is to

assure credibility and integrity in the industry in India. They have developed a “Code of

Ethical Practice”, “which stipulates that they must provide services to students in a

manner which reflects the established practices of Australian education and training

institutions and which safeguards the interests of prospective students on the other.”

Http://www.aaeri.org/home.htm

These trained and registered agents have agreed to be fair and honest in their dealing

with students, so we should have greater confidence in their level of service.

The biggest risk is to the reputation of the organisation. It is too late when an institution

is caught up in a situation of corruption, poor practice and mishandling. It is naïve to

assume that every one has the same attitude about integrity. As Locke suggests, best

practice companies understand that their reputation is an economic asset and needs to

be actively managed. There is a need to engage management as well as staff in the

process of protecting and enhancing that reputation.

Butler, asserts that concepts such as risk management need to engage employees as

essential component of reputation management and communication. A proactive

approach is to know your staff and partner’s core values as these are integral to your

institution’s reputation. Protocols and procedures around selection and appointment of

staff and agents to ensure our values are known and understood leads to better partners

and staff. Credibility, honesty and ethics are all interconnected and staff and agents can

contribute to the development of better systems and procedures and improve the

organisation’s resistance to fraud and corruption.

Australian International Education Conference 2007 10

www.idp.com/aiec

“In the long run, curbing corruption requires changing the attitudes and behaviors of both

the operators and users of the educational system, with a view to improving

transparency and accountability in the management of the system, mobilizing society

against corruption and, hopefully, paving the way for deep social transformation.” (Hallak

& Poisson 2007, p. 283)

A national register of education agents would be a valuable and important construct for

this industry and a key element of the industry’s reputation risk management. Perhaps it

could be a self-selecting list generated by the education agents themselves. It should be

underpinned by ethics training and a declaration of their commitment to a code of ethical

conduct. A code of conduct for education agents and a public record of who have

committed to best ethical practice would go a long way toward enhancing the Australian

education industry’s reputation for integrity and quality of service. As we have seen, a

reputation for robust risk management can be effectively leveraged.

References

Butler, B, 2007, Engaging Employees In Reputation Management Strategy: Aligning

Internal and External Communication, 2nd Annual Managing Reputation Risk

Conference, Melbourne, 22-23 March 2007

Cohen, D, 14 Oct 2005, in an article titled ‘A tarnished Reputation, The Chronicle of

Higher Education , (52.8), University of Newcastle, Australia

Degrees of Deception, A comprehensive Guide to Counterfeit Educational Documents,

Published by UK NARIC (ECCTIS Ltd) Oreil House, Cheltenham, UK , 2007

Ewart, H 2007, Tertiary industry demands Governmen action over student recruitment

trade, 5 April 2007 Australian Broadcasting Corporation Transcripts

(c) 2007 Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Fraud and Corruption Control Guidelines for Best Practice March 2005 (Crime and

Misconduct Commission, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 2005)

Garrett, R 2005, Fraudulent, sub-standard, ambiguous- the alternative borderless higher

education, Issue 24 July 2005 The Observatory on Borderless Higher Education,

John Foster House, London (2005).

Garrett, R 2004, Global Education Index 2004, Part 2. Public companies- relationships

with non-profit higher education, The Observatory on Borderless Higher Education,

John Foster House, London. 2 (2004).

Hallak, J. & Poisson, M., Corrupt schools, corrupt universities: What can be done?

International Institute for Educational Planning 2007, Paris

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO)

Hawthorne, L., 2007, Outcomes- language, employment and further study, Discussion

Paper, for a National Symposium: English Language Competence of International

Students, August 2007, commissioned by Australian Education International in the

Department of Education, Science and Training (DEST)

Australian International Education Conference 2007 11

www.idp.com/aiec

Immigration Advisers Welcome Licensing Law

Media Release – NZPA, 2 May 2007, Mediacom (c) 2007 New Zealand Press

Association

Locke, L, 2007, Reputation and Issues Management , at the 2nd Annual Managing

Reputation Risk Conference, Melbourne, 22-23 March 2007

NSW Public Accounts Committee Inquiry into Academics’ Paid Outside Work in (2004)

Public Accounts Committee Inquiry into Academics’ Paid Outside Work Report No.

7/53 (150) – September 2004 New South Wales. Public Accounts Committee

[Sydney, N.S.W.] At head of title: Legislative Assembly. Chair: Matt Brown. ISBN

0734766319

Rout, M 2007, Foreign students don't come cheap, 29 August 2007, The Australian p 23.

Smith, R. G 2005, Identification processes in the higher education sector: risks and

countermeasures, Trends & Issues in Criminal justice No.305,December 2005

Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra ACT

Schemo, D. J 2007, In Study Abroad, Gifts and Money for Universities, The New York

Times, August 13 2007 <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/13abroad.html>

Turner, M, 2007 Investigating the Critical Link between Reputation Risk Management

and Corporate Governance, Regulations and Compliance Standards at the 2nd

Annual Managing Reputation Risk Conference, Melbourne, 22-23 March 2007

<www.aaeri.org/home.htm>

<www.auqa.edu.au/gp/search/detail.php?gp_id=2819>

<www.scamwatch.gov.au>.

Australian International Education Conference 2007 12

www.idp.com/aiec

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Fill-InDocument2 pagesFill-InMelissaMeredithPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter One 1.0Document16 pagesChapter One 1.0Eet's Marve RichyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ebusiness 1Document4 pagesEbusiness 1Cristian WeiserPas encore d'évaluation

- A Warning - The Fake Loan Offer ScamDocument37 pagesA Warning - The Fake Loan Offer ScamKent White100% (1)

- Trust Accounting Guidelines 2018 PDFDocument32 pagesTrust Accounting Guidelines 2018 PDFdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Trust Accounting Guidelines 2018 PDFDocument32 pagesTrust Accounting Guidelines 2018 PDFdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Knowbe4 CyberheistV3Document305 pagesKnowbe4 CyberheistV3razan essaPas encore d'évaluation

- 123 Street: City: Zip 12345 Toll Free: (800) 123-XXXX (USA) Fax: (123) 345-XXXXDocument2 pages123 Street: City: Zip 12345 Toll Free: (800) 123-XXXX (USA) Fax: (123) 345-XXXXBrandyPas encore d'évaluation

- Id 3237Document3 pagesId 3237Foy Angulo Hernández100% (1)

- Fraud and Making Off Without Payment: LAW04: Criminal Law (Offences Against Property)Document50 pagesFraud and Making Off Without Payment: LAW04: Criminal Law (Offences Against Property)Moeen AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Juul Labs v. Eonsmoke - ComplaintDocument188 pagesJuul Labs v. Eonsmoke - ComplaintSarah BursteinPas encore d'évaluation

- Debate ID SystemDocument19 pagesDebate ID SystemjosefPas encore d'évaluation

- Prepared By:-Gaurav Sanadhaya SECTION:-B2804 ROLL NO.: - RB2804B44 REG. NO.: - 10807805Document18 pagesPrepared By:-Gaurav Sanadhaya SECTION:-B2804 ROLL NO.: - RB2804B44 REG. NO.: - 10807805gauravsanadhyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Faculty Manual Update 20051Document68 pagesFaculty Manual Update 20051Ronaldyn DabuPas encore d'évaluation

- Signed Terms of AgreementDocument5 pagesSigned Terms of Agreementbro100% (1)

- SCS 200 Research Check 2Document6 pagesSCS 200 Research Check 2Robin McFaddenPas encore d'évaluation

- Top Credit Unions That Pull Equifax PDFDocument1 pageTop Credit Unions That Pull Equifax PDFklg.consultant2366Pas encore d'évaluation

- Technology Embarked The Issuance of New ICAO E-Passport: Case Study of Malaysia E-PassportDocument5 pagesTechnology Embarked The Issuance of New ICAO E-Passport: Case Study of Malaysia E-Passportcallmeayu100% (2)

- Documents Required For FRRODocument6 pagesDocuments Required For FRROyemen_eaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Demat Account Fraud - How To Safeguard Against Demat Account FraudDocument2 pagesDemat Account Fraud - How To Safeguard Against Demat Account FraudJayaprakash Muthuvat100% (1)

- IJSO Previous 10 Year PapersDocument155 pagesIJSO Previous 10 Year PapersTanmoy GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Scam Offer LetterDocument2 pagesScam Offer LetterMaxwell Seibert100% (1)

- Identifying and Reporting Consumer Frauds and ScamsDocument15 pagesIdentifying and Reporting Consumer Frauds and ScamsRichard BakerPas encore d'évaluation

- Adam Street (No. 11) : Money Scams, MONKWELL COMPANY PLC, 11 Adam ST, LondonDocument48 pagesAdam Street (No. 11) : Money Scams, MONKWELL COMPANY PLC, 11 Adam ST, LondonJohn Adam St Gang: Crown ControlPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Hack WPA/WPA2 Wi Fi With Kali Linux: Last Updated: June 23, 2022Document7 pagesHow To Hack WPA/WPA2 Wi Fi With Kali Linux: Last Updated: June 23, 2022123456Pas encore d'évaluation

- Australian Digital ThesisDocument194 pagesAustralian Digital ThesisGinger KalaivaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Internet Fraud DocuDocument3 pagesInternet Fraud DocuCristian PalorPas encore d'évaluation

- Advance Fee Fraud and BanksDocument10 pagesAdvance Fee Fraud and Banksbudi626Pas encore d'évaluation

- IRM TI UK Bribery Guide A5 V6 Low Res ProofDocument44 pagesIRM TI UK Bribery Guide A5 V6 Low Res ProofmohamedciaPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Company by StateDocument350 pagesList of Company by StateRevathy GanesanPas encore d'évaluation

- Nous Group Case StudyDocument18 pagesNous Group Case Studydanrulz18Pas encore d'évaluation

- Make UK Manufacturing Outlook 2023 Q1Document19 pagesMake UK Manufacturing Outlook 2023 Q1Guido FawkesPas encore d'évaluation

- Economic and Financial Crimes CommissionDocument3 pagesEconomic and Financial Crimes CommissionPascal EgbendaPas encore d'évaluation

- TALY USA V Jason Nissen - Civil ComplaintDocument53 pagesTALY USA V Jason Nissen - Civil ComplaintC Beale100% (1)

- Avoid Employment ScamsDocument1 pageAvoid Employment ScamsTMJ4 NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Bcci ScamDocument4 pagesBcci ScamAli HaiderPas encore d'évaluation

- DocumentsDocument8 pagesDocumentsPeggy Sue EdmondsPas encore d'évaluation

- COVID 19 Unemployment AssistanceDocument4 pagesCOVID 19 Unemployment AssistanceDennis GarrettPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Methodology Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument35 pagesResearch Methodology Microsoft Office Word DocumentSameer VelaniPas encore d'évaluation

- TFNDocument8 pagesTFNAlejandroMariñoPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Unemployment?Document8 pagesWhat Is Unemployment?Arsema ShimekitPas encore d'évaluation

- Why We All Fall For Con ArtistsDocument5 pagesWhy We All Fall For Con ArtistsRichardPas encore d'évaluation

- Scott Harris Bloom: DisclaimerDocument20 pagesScott Harris Bloom: DisclaimerTô Hải HàPas encore d'évaluation

- 04.03.23 Re IRNewswires Organized Crime Investigations Issues Worldwide Scam AlertDocument17 pages04.03.23 Re IRNewswires Organized Crime Investigations Issues Worldwide Scam AlertThomas WarePas encore d'évaluation

- Basaha Tarong Inig Exam Kay Libog Ang Answer Ani Sa Reviwer (Uwu)Document5 pagesBasaha Tarong Inig Exam Kay Libog Ang Answer Ani Sa Reviwer (Uwu)trako truckPas encore d'évaluation

- Generate A Random Name - Name GeneratorDocument3 pagesGenerate A Random Name - Name GeneratorpamahevPas encore d'évaluation

- Food Stamp Calculator Oct 2015 X LsDocument24 pagesFood Stamp Calculator Oct 2015 X Lsjesi5445Pas encore d'évaluation

- BBB Says Beware of Grant ScamsDocument1 pageBBB Says Beware of Grant ScamsbmoakPas encore d'évaluation

- Scam Baiting: Key VocabularyDocument3 pagesScam Baiting: Key VocabularyМария СавенкоPas encore d'évaluation

- DFI BrochureDocument21 pagesDFI BrochureSuhaib Ahmed ShajahanPas encore d'évaluation

- V JZ 7 MMH HDocument12 pagesV JZ 7 MMH HSebyTazGonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Immigrant Visa - Review Personal, Address, Phone, and Passport InformationDocument2 pagesNon-Immigrant Visa - Review Personal, Address, Phone, and Passport InformationTie PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is 'Forensic Accounting': TypesDocument5 pagesWhat Is 'Forensic Accounting': TypesBhaven SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Sy0 501 PDFDocument13 pagesSy0 501 PDFAdnan MirPas encore d'évaluation

- Detection of Spams Using Extended ICA & Neural NetworksDocument6 pagesDetection of Spams Using Extended ICA & Neural NetworksseventhsensegroupPas encore d'évaluation

- Queens-Based Counterfeit Credit Card Ring DismantledDocument4 pagesQueens-Based Counterfeit Credit Card Ring DismantledNew York PostPas encore d'évaluation

- Free Download 3gp Mp4 Avi Movies For MobilesDocument4 pagesFree Download 3gp Mp4 Avi Movies For MobilesYasir Mehmood Butt33% (3)

- Home For Consumers: Avoid ScamsDocument4 pagesHome For Consumers: Avoid ScamsAbang NurazlyPas encore d'évaluation

- Cyber Unit 2 PPT - 1597466308-1 - 1606227791Document57 pagesCyber Unit 2 PPT - 1597466308-1 - 1606227791signup onsitesPas encore d'évaluation

- Romance Scams Take Record Dollars in 2020: Data SpotlightDocument3 pagesRomance Scams Take Record Dollars in 2020: Data SpotlightTim McGuinnessPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Security Numbers and CardsDocument2 pagesSocial Security Numbers and CardsHector HurtadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Experian Data Breach: Frequently Asked Questions For Individual ClientsDocument3 pagesExperian Data Breach: Frequently Asked Questions For Individual ClientsYusheel RamruthenPas encore d'évaluation

- Merchant Cash Factoring Business Cash LoansDocument2 pagesMerchant Cash Factoring Business Cash LoansMerchantCashinAdvancePas encore d'évaluation

- Australian Mygov Security IssuesDocument6 pagesAustralian Mygov Security IssuesnikcubPas encore d'évaluation

- HyperDocument3 pagesHyperdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- LAW547 - 602 Dec 2016Document4 pagesLAW547 - 602 Dec 2016darwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- HyperDocument3 pagesHyperdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- INV0001Document1 pageINV0001darwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- HyyDocument3 pagesHyydarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- PlanBIpoh byBIG PDFDocument10 pagesPlanBIpoh byBIG PDFdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Wong Hon Leong David v. Noorazman Bin AdnanDocument7 pagesWong Hon Leong David v. Noorazman Bin AdnandarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pizza Dude Dot DKDocument1 pagePizza Dude Dot DKCahyo SnPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial Relations Act (Act 177)Document76 pagesIndustrial Relations Act (Act 177)Muhammad Farid AriffinPas encore d'évaluation

- 12 Thelawoftheunitednations 130614100203 Phpapp02 140513203140 Phpapp01Document50 pages12 Thelawoftheunitednations 130614100203 Phpapp02 140513203140 Phpapp01darwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- ShyFoundry Freeware EULA PDFDocument2 pagesShyFoundry Freeware EULA PDFMusty HoedPas encore d'évaluation

- SARDocument10 pagesSARdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- DR Shanmuganathan V Periasamy Sithambaram PillaiDocument35 pagesDR Shanmuganathan V Periasamy Sithambaram PillaidarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Tun Datu Hj. Mustapha Datu HarunDocument24 pagesTun Datu Hj. Mustapha Datu HarundarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Awareness Raising MeasuresDocument9 pagesAwareness Raising MeasuresdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Dworkin'S Theory of Interpretation and The Nature of JurisprudenceDocument27 pages3 Dworkin'S Theory of Interpretation and The Nature of JurisprudenceMonica SalasPas encore d'évaluation

- DR Shanmuganathan V Periasamy Sithambaram PillaiDocument35 pagesDR Shanmuganathan V Periasamy Sithambaram PillaidarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- NST Govt Mulling Stronger Laws Battle Against Human TraffickingDocument5 pagesNST Govt Mulling Stronger Laws Battle Against Human TraffickingdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 5 & 6 RM, Data Collection & AnalysisDocument29 pagesWeek 5 & 6 RM, Data Collection & AnalysisdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Roe V WadeDocument2 pagesRoe V WadedarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- 33 Outline 092 VDDDDocument6 pages33 Outline 092 VDDDdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Act 670Document59 pagesAct 670Renuka JeyabalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 11 - Rights and Liberties in MalaysiaDocument3 pagesArticle 11 - Rights and Liberties in MalaysiadarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Arguement Mapping 2Document1 pageArguement Mapping 2darwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Abortion Brings More Good Than HarmsDocument1 pageAbortion Brings More Good Than HarmsdarwiszaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- JOHANSSON - ChapDocument29 pagesJOHANSSON - Chaplow profilePas encore d'évaluation

- Global TeachrDocument30 pagesGlobal TeachraldinettePas encore d'évaluation

- King George's Medical University, Lucknow: (MBBS)Document9 pagesKing George's Medical University, Lucknow: (MBBS)JAGGA GAMING OFFICIALPas encore d'évaluation

- Free EducationDocument11 pagesFree EducationJoanMagnoMariblancaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rank Appno. Name NEET UG 2023 Roll Number Neet Mark: Page 1 of 440Document440 pagesRank Appno. Name NEET UG 2023 Roll Number Neet Mark: Page 1 of 440akk895555Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Nine-Year Schooling On Higher Learning in MauritiusDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Nine-Year Schooling On Higher Learning in MauritiusAnushka SeebaluckPas encore d'évaluation

- ANNOUNCEMENT FOR ADMITTED APPLICANTS SEPTEMBER INTAKE 2022-2023 FOR THE WEBSITE - CompressedDocument176 pagesANNOUNCEMENT FOR ADMITTED APPLICANTS SEPTEMBER INTAKE 2022-2023 FOR THE WEBSITE - CompressedLuciana100% (1)

- The Kaplan Advantage BrochureDocument24 pagesThe Kaplan Advantage BrochureMyu Wai ShinPas encore d'évaluation

- By Ina Alleco R. SilverioDocument6 pagesBy Ina Alleco R. SilverioJun Reyes RamirezPas encore d'évaluation

- Uttarakhand Round 2 Revised Allotment Dated 29oct 5pmDocument264 pagesUttarakhand Round 2 Revised Allotment Dated 29oct 5pmPrudhvi MadamanchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Tokyo Tech - Useful LinkDocument1 pageTokyo Tech - Useful LinkTanujPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibiolographyDocument8 pagesAnnotated Bibiolographyapi-468022280Pas encore d'évaluation

- Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat: CentreDocument6 pagesVeer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat: CentreTushar RajPas encore d'évaluation

- Rev Mds Merit Gen 010519Document16 pagesRev Mds Merit Gen 010519kalelPas encore d'évaluation

- The Survey and Analysis of Social Science Higher Education Material Production Initiative in Kannada: Translation Strategies, Story of Success/Failures ReportDocument240 pagesThe Survey and Analysis of Social Science Higher Education Material Production Initiative in Kannada: Translation Strategies, Story of Success/Failures ReportTharakeshwar VbPas encore d'évaluation

- Colleges With The Highest SAT ScoresDocument3 pagesColleges With The Highest SAT ScoresMariana LloredaPas encore d'évaluation

- UJ Undergraduate Prospectus2019 ONLINE Updated Jul2018Document51 pagesUJ Undergraduate Prospectus2019 ONLINE Updated Jul2018Pre TshuksPas encore d'évaluation

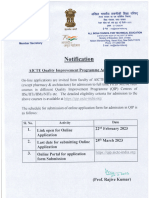

- Notification of QIP Admission 2023 1Document1 pageNotification of QIP Admission 2023 1mahendrajadhav007mumbaiPas encore d'évaluation

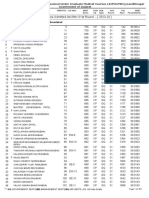

- InstwiseadmDocument191 pagesInstwiseadmFhu Gg9yPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Indian Graduates Are UnemployableDocument5 pagesWhy Indian Graduates Are UnemployableSteffy SoniyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Muet Writing AswersDocument10 pagesMuet Writing AswersAfiq AmeeraPas encore d'évaluation

- To All Interested Applicants For The Master of Architecture CourseDocument3 pagesTo All Interested Applicants For The Master of Architecture CourseFurqan ArchPas encore d'évaluation

- Pragati Engineering College: Surampalem Date: 12-06-2016 From The Head of The DepartmentDocument3 pagesPragati Engineering College: Surampalem Date: 12-06-2016 From The Head of The DepartmentsubhansamuelsPas encore d'évaluation

- 300 - Scholarships ListDocument1 page300 - Scholarships ListArnav RastogiPas encore d'évaluation

- Second Admission ListDocument17 pagesSecond Admission ListTek Singh AyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Joint Entrance Examination (Main) - India 20 Jan 2024Document1 pageJoint Entrance Examination (Main) - India 20 Jan 2024vibhsm24Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On Higher Education in Bangladesh PDFDocument15 pagesA Study On Higher Education in Bangladesh PDFJerin100% (3)

- Legitimating Industrial Design As An Academic Discipline in The Context of An Australian Cooperative CentreDocument5 pagesLegitimating Industrial Design As An Academic Discipline in The Context of An Australian Cooperative CentreSebastian MayaPas encore d'évaluation