Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Curriculum Contrasts: Historical Overview: by Allan C. Ornstein

Transféré par

Wayne David C. PadullonTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Curriculum Contrasts: Historical Overview: by Allan C. Ornstein

Transféré par

Wayne David C. PadullonDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Curriculum Contrasts:

A Historical Overview

by Allan C. Ornstein

The curriculum is the heart

T

of every school program. Mr.

Ornstein presents a curriculum

he most fundamental concern of of facts and concepts learned in isolation. primer - detailing the most

schooling is curriculum. Students They see this kind of curriculum as de- important curriculum

tend to view schooling largely as subjects emphasizing life experiences and failing to

or courses to be taken. Teachers and pro- consider adequately the needs and in- movements, their adherents,

fessors give much attention to adoption terests of students. The emphasis, such and their rationales.

and revision of subject matter. Parents critics argue, is on the teaching of

and community members frequently ex- knowledge, the recall of facts. Thus the

press concern about what schools are for teacher dominates the lesson, allowing lit-

and what they should teach. In short, all tle student input. Let us look at five varia-

of these groups are attending to one thing: tions on the subject-centered curriculum.

curriculum. Subject-Area Curriculum. The subject

Curriculum concepts and scope have area is the oldest and most widely used

changed over the years, and from these form of curriculum organization. It has its

changes two differing views of curriculum roots in the seven liberal arts of classical

have emerged. The first sees curriculum as Greece and Rome: grammar, rhetoric,

a body of content or subject matter dialectic, arithmetic, geometry, astrono-

leading to certain achievement outcomes my, and music. Modern subject-area cur-

or products. The second views curriculum ricula trace their origins to the work of

in terms of the learner and his or her William Harris, superintendent of the St.

needs; the concern is with process, i.e., Louis school system in the 1870s. Steeped

the climate of the classroom and school. in the classical tradition, Harris estab-

lished a subject orientation that has vir-

The Subject-Centered Curriculum tually dominated U.S. curricula from his

day to the present.

Subject matter is the oldest and most The modern subject-area curriculum

used framework for curriculum organiza- treats each subject as a specialized and

tion, primarily because it is convenient. In largely autonomous body of verified

fact, the departmental structure of secon- knowledge. These subjects can be or-

dary schools and colleges tends to prevent ganized into three content categories,

us from thinking about the curriculum in however. Common content refers to sub-

other ways. Curricular changes usually oc- jects considered essential for all students;

cur at the departmental level. Courses are these subjects usually include the three R’s

added, omitted, or modified, but faculty at the elementary level and English, his-

members rarely engage in comprehensive, tory, science, and mathematics at the

systematic curriculum development and secondary level. Special content refers to

evaluation. Even in the elementary subjects that develop knowledge and skills

school, where self-contained classrooms for particular vocations or professions,

force the teachers to be generalists, cur- e.g., business mathematics and physics.

ricula are usually organized by subjects. Finally, elective content affords the stu-

Proponents defend the subject-cen- dent optional offerings. Some electives

tered curriculum on four grounds: 1) that are restricted to certain students, e.g., ad-

subjects are a logical way to organize and vanced auto mechanics for vocational stu-

interpret learning, 2) that such organiza- dents or fourth-year French for students

tion makes it easier for people to remem- enrolled in a college-preparatory pro-

ber information for future use, 3) that gram. Other electives, such as photogra-

teachers (in secondary schools, at least) phy and human relations, are open to all

are trained as subject-matter specialists, students.

and 4) that textbooks and other teaching Perennialist Curriculum. Two con-

materials are usually organized by subject. servative philosophies of education are

Critics, however, claim that the subject- basically subject-centered: Perennialism

1

centered curriculum is fragmented, a mass and Essentialism. Perennialists believe

that a curriculum should consist primarily

of the three R’s, Latin, and logic at the

ALLAN C. ORNSTEIN is professor of elementary level, to which is added the

education, Loyola University of Chicago. study of the classics at the secondary level.

404 PHI DELTA KAPPAN

The assumption, according to Robert learn how to learn. But they tended to mar, not linguistics or nonstandard Eng-

Hutchins, is that the best of the past — dismiss learners’ social and psychological lish; it means Shakespeare and Words-

the so-called “permanent studies” or2 needs. As Philip Phenix wrote: “There is worth, not Catcher in the Rye or Lolita.

classics — is equally valid for the present. no place in the curriculum for ideas which Creative writing is frowned upon. Science

One problem with Perennialism is its are regarded as suitable for teaching be- means biology, chemistry, and physics —

fundamental premise: that the main pur- cause of the supposed nature, needs, and not ecology. Mathematics means old

pose of education is the cultivation of the interests of the learner, but which do not math, not new math. Furthermore, these

intellect. Further, Perennialists believe belong within the regular structure of the subjects are required. Proponents of the

4

that only certain studies have this power. discipline.“ basics consider elective courses in such

They reject consideration of students’ per- The emphasis on structure led each dis- areas as scuba diving, transcendental

sonal needs and interests or the treatment cipline to develop its own unifying con- meditation, and hiking as nonsense. Some

of contemporary problems in the curricu- cepts, principles, and methods of inquiry. even consider humanities or integrated

lum on the ground that such concerns are Learning by the inquiry method in chem- social science courses too “soft.” They

frivolous and detract from the school’s istry differs from learning by the inquiry may grudgingly admit music and art into 8

mission of cultivating the mind. method in physics, for example. More- the program — but only for half credit.

Essentialist Curriculum. Essentialists over, curriculum planners could not agree These proponents believe that too

believe that the curriculum must consist of on how to teach the structure of the social many illiterate students pass from grade to

“disciplined study” in five areas: English sciences and the fine arts. Science and grade and eventually graduate, that high

(grammar, literature, and writing), mathe- mathematics programs continue even to- school and college diplomas are meaning-

matics, the sciences, history, and foreign day to provide the best examples of less as measures of graduates’ abilities,

3

languages. They see these subject areas as teaching the structure of a subject. that minimum standards must be set, that

the best way of systematizing and keeping Back-to-Basics Curriculum. A strong the basics (reading, writing, math) are

up with the explosion of knowledge. back-to-basics movement has surfaced essential for employment, and that stu-

Essentialism shares with Perennialism among parents and educators, called forth dents must learn survival skills to function

the notion that the curriculum should by the general relaxation of academic effectively in society. Some back-to-basics

focus on rigorous intellectual training, a standards in the Sixties and Seventies and advocates are college educators who

training possible only through the study declining student achievement in reading, would do away with open admissions or

of certain subjects. Although the Peren- writing, and computation. Automatic relaxed entrance requirements and grade

nialist sees no need for nonacademic sub- promotion of marginal students, the inflation; they would simply insist that

jects, the Essentialist is willing to add such dizzying array of elective courses, and their institutions require students to meet

studies to the curriculum, provided they textbooks designed more to entertain than a reasonable standard in the basic dis-

receive low priority. to educate are frequently cited as sources ciplines — that students be able to under-

Both Perennialists and Essentialists ad- of the decline in basic skills. Even the stand homework assignments, write ac-

vocate an educational meritocracy. They mass media have attacked the “soft-sell ceptable9 essays, and compute numbers ac-

favor high academic standards and a approach” to education. The concerns curately.

rigorous system of testing to help schools voiced today parallel, to some extent, Critics point out that the decline in

sort students by ability. The goal is to those voiced immediately after Sputnik. standardized achievement test scores — a

educate each person to the limits of his or The call is less for academic excellence and grave concern of back-to-basics enthu-

her potential. rigor, however, than for a return to siasts — may be linked less to curriculum

Subject Structure Curriculum. During basics. Annual Gallup polls have asked than to higher student/teacher ratios, a

the Fifties and Sixties, the National Sci- the public to suggest ways for improving decrease in the number of low-achieving

ence Foundation and the federal govern- education; since 1975 “devoting more at- students who drop out of school, and the10

ment devoted sizable sums to the improve- tention to teaching the basics” has either more permissive attitude of society.

ment of science and mathematics curricu- headed the list of5 responses or ranked no There is no guarantee, they argue, that the

la at the elementary and secondary levels. lower than third. student who masters specific skills for to-

The result was new curricular models for- By 1978, 33 states had set minimum day’s world will be better prepared for the

mulated according to the structure of each standards for elementary and secondary world of tomorrow. They also worry that

subject or discipline. Structure includes students. All the remaining states have a narrow focus on basics will suppress

those unifying concepts, rules, and prin- legislation pending or are studying the sit- students’ creativity, encouraging instead

6

ciples that define and limit a subject and uation. The National Association of Sec- conformity

11

and dependence on author-

control the methods of research and in- ondary School Principals (NASSP) rec- ity. Others expect the back-to-basics

quiry. Structure brings together and or- ommends the use of certificates of pro- movement to fail because teaching and

ganizes a body of knowledge, as well as ficiency for all students, whether or not learning cannot be defined and limited

dictating appropriate ways of thinking minimal proficiency is made a require- precisely and because testing has too

about the subject and of generating new ment for graduation. Congress is also urg- many inherent problems.

data. Other subjects quickly followed the ing voluntary adoption by state and local While the debate is raging, the move-

lead of mathematics and the sciences. education agencies of minimum compe- ment is spreading quickly in response to

7

Those who advocated this kind of tency testing programs. public pressure. State legislators and state

focus on structure nonetheless rejected the Although the back-to-basics move- boards of education seem convinced of

idea of knowledge as fixed or permanent. ment means different things to different the merit of minimum standards. But

They regarded teaching and learning as people, it usually connotes an Essentialist there are also unanswered questions. If we

continuing inquiry, but they confined curriculum with heavy emphasis on read- adopt a back-to-basics approach to educa-

such inquiry within the established bound- ing, writing, and mathematics. Solid sub- tion, what standards

12

should be considered

aries of subjects, ignoring or rejecting jects — English, history, science, mathe- minimum? Who determines these stan-

the fact that many problems cut across matics — are taught in all grades. History dards? What do we do with students who

disciplines. Instead, they emphasized the means U.S. and European history and fail to meet these standards? Are we sim-

students’ cognitive abilities. They taught perhaps Asian and African history, but ply punishing the victims for the schools’

students the structure of a subject and its not Afro-American history or ethnic inability to educate them? How will the

methods of inquiry so that students would studies. English means traditional gram- courts deal with the fact that proportion-

FEBRUARY 1982 405

“Progressive educators believed that, when the

interests and needs of learners were incorporated

into the curriculum, intrinsic motivation resulted.”

ally more minority than white students fail Child-Centered Schools. The move- will study and those who prefer not to

the competency tests in nearly every state ment from the traditional subject-domi- study will not, regardless of how teachers

that has a testing program?13 Is the issue nated curriculum toward a program em- teach. Neill’s dual criteria for success were

minimum competence, or is it equal edu- phasizing student interests and needs the ability to work joyfully and the ability

cational opportunity? began in 1762 with the publication of to live a happy life.

Rousseau’s Emile. In this book Rousseau Although Neill, Edgar Friedenberg,

18

The Student-Centered Curriculum maintained that the purpose of education Paul Goodman, and John Holt all be-

is to teach people to live. Early in the next long to an earlier generation of school re-

If the subject-centered curriculum century the Swiss educator, Johann Pesta- formers, new radicals have also emerged.

focuses on cognitive aspects of learning, lozzi, began to stress human emotions and They include George Dennison, James

the student-centered curriculum empha- kindness in teaching young children. Herndon, Ivan Illich, Herbert Kohl, and

sizes students’ interests and needs. The Friedrich Froebel introduced the kinder- Jonathan Kozol. These educators stress

student-centered approach, at its extreme, garten in Germany in 1837. He empha- the need for and in many cases have es-

is rooted in the philosophy of Jean sized a permissive atmosphere and the use tablished child-centered free schools or

19

Jacques Rousseau, who encouraged child- of songs, stories, and games as instruc- alternative schools. These schools are

hood self-expression. tional materials. Early in the 20th century typified by a great deal of freedom for stu-

Implicit in Rousseau’s philosophy is Maria Montessori, working with the slum dents and noisy classrooms that some-

the necessity of leaving the child to his or children of Rome, developed a set of times appear untidy and disorganized.

her own devices; he considered creativity didactic materials and learning exercises The teaching/learning process is unstruc-

and freedom essential for children’s that successfully combined work with tured.

growth. Moreover, he thought a child play. Many of her principles were intro- Critics condemn these schools as places

would be happier if free of teacher domi- duced in the U.S. during the Sixties as where little cognitive learning takes place.

nation and the demands of subject matter part of the compensatory preschool move- They decry a lack of discipline and order.

and adult-imposed curriculum goals. This ment. They feel that the radical reformers’ at-

hands-off policy was Rousseau’s reaction Early Progressive educators in the U.S. tacks on Establishment teachers and

to the domineering teacher of the tradi- adopted the notion of child-centered schools are overgeneralized and unfair.

tional school, whose sole purpose was to schools, starting with Dewey’s organic Moreover, they view the radicals’ idea of

drill facts into a child’s brain. school (which he described in Schools of schooling as not feasible for mass educa-

Progressive education gave impetus to Tomorrow) and including many private tion. Proponents counter that children do

the student-centered curriculum. Progres- and experimental schools - the best learn in these schools, which do not stress

sive educators believed that, when the in- known of which were Columbia Univer- conformity but instead are made to fit the

terests and needs of learners were in- sity’s Lincoln School, Ohio State’s Labo- child.

corporated into the curriculum, intrinsic ratory School, the University of Missouri Activity-Centered Curriculum. This

motivation resulted. I do not mean to im- Elementary School, the Pratt Play School movement, which grew out of the private

ply that the student-centered curriculum is in New York City, the Parker School in child-centered schools, strongly affected

dictated by the whims of the learner. Chicago, and the Fairhope School in Ala- the public elementary school curriculum.

Rather, advocates believe that learning is bama. 16 These schools had a common William Kilpatrick, a student of Dewey’s,

more successful if the interests and needs feature: Their curricula stressed the needs was its leader. In 1918 Kilpatrick wrote

of the learner are taken into account. The and interests of the students. Some a theoretical article, “The Project Meth-

student-centered curriculum sometimes stressed individualization; others grouped od,” that catapulted him into national

overlooks important cognitive content, students by ability or interests. prominence. He advocated purposeful ac-

however. Child-centered education is repre- tivities that were

20

tied to a child’s needs

John Dewey, one of the chief advo- sented today by programs for such special and interests. Kilpatrick differed with

cates of the student-centered curriculum, groups as the academically talented, the Dewey’s child-centered view; he believed

criticized educators who overlooked the disadvantaged, dropouts (actual and po- that the interests and needs of children

importance of subject matter. His inten- tential), the handicapped, and minority could not be anticipated, making a pre-

tion was to establish a curriculum that and ethnic groups. Many of these pro- planned curriculum impossible. He at-

balanced subject matter with student in- grams are carried on in “free” or “al- tacked the school curriculum as unrelated

terests and needs. As early as 1902, he ternative” schools organized by parents to the problems of real life and advocated

pointed out the fallacies of either extreme. and teachers who are dissatisfied with the purposeful activities that were as lifelike

The learner was neither “a docile recipient public schools. Most of these new schools as possible.

of facts” nor “the starting point, the 14 are considered radical and anti-Establish- During the Twenties and Thirties,

center, and the end” of school activity. ment, even though many of their ideas are many elementary schools adopted some of

More than 30 years later, Dewey was still rooted in the child-centered doctrines of the ideas of the activity movement, per-

criticizing overpermissive educators who Progressivism. haps best summarized and first put into

provided little education for students Summerhill, a school founded in 1921 practice by Ellsworth Collings, a doctoral

21

under the guise of meeting

15

their expressed by A. S. Neil1 and still in existence today, student of Kilpatrick's. From this move-

and impulsive needs. Dewey sought in- is perhaps the best-known free school. ment a host of teaching strategies

stead to use youngsters’ developing inter- Neill’s philosophy was the replacement of emerged, including lessons based on life

ests to enhance the cognitive learning authority by freedom.17 He was not con- experiences, group games, dramatiza-

process. cerned with formal learning; he did not tions, story projects, field trips, social

There are at least five variations of the believe in textbooks or examinations. He enterprises, and interest centers. All of

student-centered curriculum. did believe that those who want to study these activities involved problem solving

406 PHI DELTA KAPPAN

"[C]hanges made in the name of relevance

have led to a watered-down curriculum.”

and active student participation; they em- dom of choice; and 4) the extension of order to further the purposes of the

phasized socialization and the formation the curriculum beyond the school’s walls school? Or should they try to incorporate

of stronger school/community ties. through such innovations as work-study it into school life? At what age is the stu-

Recent curriculum reformers have programs, credit for life experiences, and dent mature enough to discuss such sen-

translated ideas from this movement into external degree programs. 27 sitive topics as racial and ethnic stereo-

community and career-based activities in- Efforts to relate subject matter to stu- types? A student-oriented school, some

tended to prepare students for adult citi- dent interests have been largely ad hoc. educators contend, would try to reduce

zenship and work and into courses em- Many of the changes have also been frag- the disparity between the student’s world

30

phasizing social problems. They have also 22

mentary and temporary, a source of con- outside of school and that within.

urged college credit for life experiences. cern to advocates of relevance. In other Humanistic Curriculum. Like many

Secondary and college students often earn cases, changes made in the name of rele- other modern curriculum developments,

credit today by working in welfare agen- vance have led to a watered-down curricu- humanistic education was a reaction to

cies, early childhood programs, govern- lum. the emphasis on cognitive learning in the

ment institutions,

23

hospitals, and homes Hidden Curriculum. The notion of a late Fifties and early Sixties. Terry Bor-

for the aged. hidden curriculum implies that values of ton, a Philadelphia schoolteacher, was

Relevant Curriculum. Unquestionably, the student peer group are often ignored one of the first to write about this move-

the curriculum must reflect social change. when formal school curricula are planned. ment. He contended that education in the

This point is well illustrated in a satiric C. Wayne Gordon was one of the first Seventies had only two major purposes: 31

book on education, The Saber-Tooth educators to describe the hidden curricu- subject mastery and personal growth.

Curriculum, written in 1939 by Harold lum — the "informal school system” that Nearly every school’s statement of objec-

28

Benjamin under the pseudonym of Abner affects what is learned. Gordon argued tives includes both purposes, but Borton

24

J. Peddiwell. He describes a society in that students’ achievement and behavior saw the objectives related to personal

which the schools continued to teach fish- are related to their status and roles in growth and to values, feelings, and the

catching (because it would develop agil- school; he also suggested that informal happy life as "only for show. Everyone

ity), horse-clubbing (to develop strength), and unrecognized cliques of students con- knows how 32

little schools have done about

and tiger-scaring (to develop courage) trol much of adolescent performance both [them]. " Borton believed that the time

long after the streams had dried up and inside and outside of school. These cliques had come for schools to put their noble

the horses and tigers had disappeared. or factions are sometimes in conflict with phrases about children’s social and per-

The wise men of the society argued that the formal school curriculum, with text- sonal interests into practice.

"the essence of true education is time- books, and with classroom rules. In his best-selling book, Crisis in the

less . . . something that endures through The hidden curriculum also includes Classroom, Charles Silberman also advo-

33

changing conditions like a solid rock the strategies adopted by students to out- cated the humanizing of U.S. schools.

standing squarely and25firmly in the middle wit and outguess their teachers. Accord- He charged that schools are repressive,

of a raging torrent." Benjamin’s mes- ing to John Holt, “successful” students teaching students docility and conformity.

sage was simple: The curriculum was no become cunning strategists

29

in a game of He believed that schools must be re-

longer relevant. beating the system. Experience has formed, even at the price of deemphasiz-

There is a renewed concern today that taught these students that trickery and ing cognitive learning. He suggested that

the curriculum be relevant. But the em- even occasional dishonesty pay off. The elementary schools adopt the methods of

phasis has changed. We no longer worry implication is that teachers must become the British infant schools. At the sec-

so much about whether the curriculum re- more sensitive to students’ needs and feel- ondary level, he suggested independent

flects changing social conditions. Instead, ings in order to minimize counterproduc- study, peer tutoring, and community and

we are concerned that the curriculum be tive behavior. A school that encourages work experiences.

relevant to students. This shift is part of personal freedom and cooperative group The humanistic model of education

the Dewey legacy. Learners must be moti- learning - instead of competitive indi- stems from the human potential move-

vated and interested in the learning task, vidualization, lesson recitation, “right” ment in psychology. Within education it is

and the classroom should

26

build on their answers, and textbook/teacher authority rooted in the work of Arthur Jersild, who

real-life experiences. - is more conducive to learning because linked good teaching with knowledge of

The new demand for relevance comes the atmosphere is free of trickery and dis- self and students, and in the work of

from both students and educators. In honesty. Or so the argument goes. Arthur Combs and Donald Snygg, who

fact, the student disruptions of the late Another interpretation of the hidden explored the impact of self-concept and

34

1960s and early 1970s were related to this curriculum suggests that some intentional motivation on achievement. Combs and

demand. Proponents see as needs: 1) the school behavior is not formally recognized Snygg considered self-concept the most

individualization of instruction through in the curriculum or discussed in the class- important determinant of behavior.

such teaching methods as independent in- room because of its sensitivity or because A humanistic curriculum emphasizes

quiry, special projects, and contracts; 2) teachers do not consider it important. At affective rather than cognitive outcomes.

the revision of existing courses and de- the same time, students sometimes see Such a curriculum draws heavily on the

velopment of new ones on such topics of what is taught as phony, antiseptic, or work of35Abraham Maslow and of Carl

student concern as environmental protec- unrelated to the real world. For example, Rogers. Its goal is to produce "self-

tion, drug addiction, urban problems, cul- certain ethnic or minority groups are actualizing people," in Maslow's words,

tural pluralism, and Afro-American liter- discussed in a derogatory manner in some or “total human beings,” as Rogers puts

ature; 3) the provision of educational homes. This raises several questions. it. The works of both psychologists are

alternatives (e.g., electives, minicourses, Should curriculum specialists or teachers larded with such terms as maintaining,

open classrooms) that allow more free- try to suppress the hidden curriculum in striving, enhancing, and experiencing

FEBRUARY 1982 407

“The subject-centered curriculum and the student-centered

curriculum represent two extremes on a continuum. Most

schooling in the U.S. falls somewhere in between.. . ."

as well as independence, self-determina- 1978, September 1979, and September 1980 issues of 20. William H. Kilpatrick, “The Project Method,"

tion, integration, and self-actualization. Phi Delta Kappan. Teachers College Record, September 1918, pp.

6. Ben Brodinsky, “Back to the Basics! The Move- 319-35.

Advocates of humanistic education ment and Its Meaning,” Phi Delta Kappan, March 21. Ellsworth Collings, ed., An Experiment with a

contend that the present school curricu- 1977, pp. 522-27; Chris Pipho, “Minimum Compe- Project Curriculum (New York: Macmillan, 1923).

lum has failed miserably by humanistic tency Testing in 1978: A Look at State Standards,” Another description of the activity-centered program

standards, that teachers and schools are Phi Delta Kappan, May 1978, pp. 585-87; and Rodney was provided by Harold Rugg and Ann Shumaker,

P. Riegel and Ned B. Lovel, Minimum Competency The Child-Centered School: An Appraisal of the New

determined to stress cognitive behaviors Testing (Bloomington, Ind.: Phi Delta Kappa Educa- Education (Yonkers, N.Y.: World Book, 1928).

and to control students not for their

36

own tional Foundation, 1980). 22. See American Youth in the Mid-Seventies (Wash-

good. but for the good of adults. Hu- 7. James L. Jarrett, “I’m for Basics, But Let Me ington, D.C.: National Association of Secondary

manists emphasize more than affective Define Them,” Phi Delta Kappan, December 1977, School Principals, 1973); James S. Coleman et al.,

processes; they seek higher domains of pp. 235-39; and Richard M. Jaeger and Carol K. Title, Youth: Transition to Adulthood,Report of the Panel

eds., Minimum Competency Achievement Testing on Youth of the President’s Science Advisory Com-

consciousness. But they see the schools as (Berkeley, Calif.: McCutchan, 1979). mittee (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974);

unconcerned about higher planes of un- 8. Brodinsky, op. cit.; Pipho, op. cit.; and Michael National Commission on the Reform of Secondary

derstanding, enhancement of the mind, or Zieky and Samuel Livingston, Manual for Setting Education, The Reform of Secondary Education

self-knowledge. Students must therefore Standards on the Basic Skills Assessment Tests (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973); The New Secondary

Education, a Phi Delta Kappa Task Force Report

turn to such out-of-school activities as (Princeton, N.J.: Educational Testing Service, 1977).

(Bloomington, Ind.: Phi Delta Kappa, 1976); and

drugs, yoga, transcendental meditation, 9. Jarrett, op. cit.; and Martin Mayer, “Higher Edu-

cation for All?,” Commentary, February 1973, pp. U.S. Office of Education, Report of the National

group encounters, T-groups, and psycho- 37-47. Panel of High School and Adolescent Education

therapy. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Of-

10. Joyce E. Johnson, “Back to Basics? We’ve Been fice, 1974) and The Education of Adolescents (U.S.

Humanists would attempt to form There 150 Years,” Reading Teacher, March 1979, pp. Government Printing Office, 1976).

more meaningful relationships between 644-46; and Ellen V. Leininger, “Back to Basics:

23. Mario D. Fantini, The Reform of Urban Schools

Concepts and Controversy,” Elementary School Jour-

students and teachers; they would foster nal, January 1979, pp. 167-73.

(Washington, D.C.: National Education Association,

student independence and self-direction 1970).

11. Gene V. Glass, “Minimum Competence and In-

and promote greater acceptance of self competence in Florida,” Phi Delta Kappan, May 24. Harold Benjamin, The Saber-Tooth Curriculum

(New York: McGraw-Hill, 1939).

and others. The teacher’s role would be to 1979, pp. 602-5; and Arthur E. Wise, "Minimum

25. Ibid., pp. 43, 44.

help learners cope with their psychological Competency Testing: Another Case of Hyper-Ration-

alization," Phi Delta Kappan, May 1979, pp. 596-98. 26. John Dewey, Experience and Education (New

needs and problems, to facilitate self- 12. New York is the only state currently insisting that York: Macmillan, 1938).

understanding among students, and to high-school-level material be included in the minimum 27. See Donald E. Orlosky and B. Othanel Smith,

help them develop fully. competences required of graduating students. This re- Curriculum Development: Issues and Ideas (Chicago:

quirement will prevent several thousand New York Rand McNally, 1978); Louis Rubin, ed., Curriculum

A drawback to humanist theory is its Handbook: The Discipline, Current Movements, and

lack of attention to cognitive learning and students from graduating.

13. In Florida, a federal court postponed for an in- Instructional Methodology (Boston: Allyn & Bacon,

intellectual development. When asked to terim period the use of competency tests for gradua- 1977); and Daniel Tanner and Laurel Tanner, Cur-

judge the effectiveness of their curricu- tion, because the tests seemed to be punishing the vic- Development: Theory into Practice, 2nd ed.

lum, humanists generally rely on testi- tims of past discrimination. The court did not find the (New York: Macmillan, 1980).

test to be racially or culturally biased, however. 28. C. Wayne Gordon, The Social System of the

monials and subjective assessments by High School (Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1957).

students and teachers. They may also pre- 14. John Dewey, The Child and the Curriculum

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1902), pp. 8, 29. Holt, How Children Fail.

sent such materials as students’ paintings 9. 30. Mario D. Fantini and Gerald Weinstein, The

and poems or talk about “marked im- 15. John Dewey, Art and Experience (New York: Disadvantaged Child (New York: Harper & Row,

provement” in student behavior and at- Capricorn Books, 1934). 1968); Robert Goldhammer, Clinical Supervision

16. A number of these early experimental schools are (New York: Holt, 1969); and Louis E. Raths et al.,

titudes. They present very little empiri- Values and Teaching, 2nd ed. (Columbus, 0.: Merrill,

cal evidence, however, to support their discussed in detail by John Dewey and his daughter

Evelyn in Schools of Tomorrow, published in 1915. 1978).

stance. Another good source is the 1926 yearbook of the Na- 31. Terry Borton, Reach, Touch, and Teach (New

The subject-centered curriculum and tional Society for the Study of Education, a two- York: McGraw-Hi, 1970).

the student-centered curriculum represent volume work titled The Foundations of Curriculum 32. Ibid., p. 28.

two extremes on a continuum. Most and Techniques of Curriculum Construction. Law- 33. Charles A. Silberman, Crisis in the Classrom

rence Cremin’s The Transformation of the School, (New York: Random House, 1971).

schooling in the U.S. falls somewhere in published in 1961, is still another good source. Finally, 34. Arthur T. Jersild, In Search of Self (New York:

between - effecting a tenuous balance Ohio State’s Laboratory School is best summarized in Teachers College Press, 1952) and When Teachers

between subject matter and student needs, a 1938 book titled Were We Guinea Ptgs?, written by Face Themselves (New York: Teachers College Press,

between achievement outcomes and learn- the senior class. 1955); and Arthur Combs and Donald Snygg, Indi-

17. A. S. Neill, Summerhill: A Radical Approach to vidual Behavior, 2nd ed. (New York: Harper & Row,

ing climate. Child Rearing (New York: Hart, 1960). 1959). See also Arthur Combs, ed., Perceiving, Behav-

18. See Edgar Z. Friedenberg, The Vanishing Adoles- ing, Becoming, 1962 Yearbook (Washington, D.C.:

cent (Boston: Beacon, 1959); Paul Goodman, Grow- Association for Supervision and Curriculum De-

1. These two terms were coined by Theodore ing Up Absurd (New York: Random House, 1960) velopment, 1962).

Brameld in Patterns of Educational Philosophy (New and Compulsory M is-Education (New York: Horizon

York: Holt, 1950). 35. Abraham H. Maslow, Toward a Psychology of

Press, 1964); and John Holt, How Children Fail (New Being (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1962) and

2. Robert M. Hutchins, The Higher Learning in York: Pitman, 1964) and How Children Learn (New Motivation and Personality, 2nd ed. (New York:

America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, York: Delta, 1972). Harper & Row, 1970); and Carl R. Rogers, Client-

1936). 19. See George Dennison, The Lives of Children: The Centered Therapy (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951),

3. Arthur Bestor, The Restoration of Learning (New Story of the First School (New York: Random House, On Becoming a Person (Boston: Houghton Mifflin,

York: Knopf, 1956). 1969); James Herndon, The Way It Spozed to Be 1961), and On Becoming (New York: Delacorte,

4. Philip H. Phenix, “The Disciplines as Curriculum (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969); Ivan Illich, De- 1979).

Content,” in A. Harry Passow, ed., Curriculum schooling Society (New York: Harper & Row, 1971); 36. Jack R. Frankel, How to Teach About Value

Crossroads (New York: Teachers College Press, Herbert R. Kohl, The Open Classroom (New York: (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1977); and

1962), p. 64. Random House, 1969) and On T eaching (New York: Richard H. Willer, ed., Humanistic Education: Vi-

5. See the annual Gallup polls published in the De- Schocken, 1976); and Jonathan Kozol, Free Schools sions and Realities (Berkeley, Calif.: McCutchan

cember 1975, October 1976, October 1977, September (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1972). 1977).

408 PHI DELTA KAPPAN

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- College Teaching: Studies in Methods of Teaching in the CollegeD'EverandCollege Teaching: Studies in Methods of Teaching in the CollegePas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction to the scientific study of educationD'EverandIntroduction to the scientific study of educationPas encore d'évaluation

- Perspectives in Interdisciplinary and Integrative StudiesD'EverandPerspectives in Interdisciplinary and Integrative StudiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum: Fondations, Principles, and Issues: Report 3dDocument16 pagesCurriculum: Fondations, Principles, and Issues: Report 3dmala 28Pas encore d'évaluation

- Stenhouse 1968 Humanities Curriculum Project JournalDocument5 pagesStenhouse 1968 Humanities Curriculum Project JournalAntero GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Teacher and School CurriculumDocument11 pagesThe Teacher and School CurriculumJohnlloyd CuanicoPas encore d'évaluation

- TTC ReviewerDocument22 pagesTTC Reviewerjhunelmago16Pas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Nature and PurposesDocument35 pagesCurriculum Nature and PurposesRuby Jane DuradoPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 (p1) - The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumDocument58 pagesModule 2 (p1) - The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumTRISHA MAY LIBARDOSPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction to Curriculum Design in Gifted EducationD'EverandIntroduction to Curriculum Design in Gifted EducationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Chapter 1 Curriculum Essentials (Module 2 The Teacher As A Knower of Curriculum)Document52 pagesChapter 1 Curriculum Essentials (Module 2 The Teacher As A Knower of Curriculum)Soraya D. Al-ObinayPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 The Teacher As A Knower of Curriculum - Lesson 1Document37 pages4 The Teacher As A Knower of Curriculum - Lesson 1jessalyn ilada85% (13)

- Teacher Preparation - Structural and Conceptual Alternatives PDFDocument61 pagesTeacher Preparation - Structural and Conceptual Alternatives PDFPJ Gape100% (1)

- Curriculum and Its DevelopementDocument31 pagesCurriculum and Its DevelopementDherick RaleighPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 MAS 105Document10 pagesModule 2 MAS 105Snappy CookiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory of Thematic CurriculaDocument18 pagesTheory of Thematic CurriculaDwight AckermanPas encore d'évaluation

- Module Three Major Foundations of Curriculum (Philosophical FoundationsDocument7 pagesModule Three Major Foundations of Curriculum (Philosophical FoundationsshielaPas encore d'évaluation

- LECTURE 4 Blended Teaching NotesDocument10 pagesLECTURE 4 Blended Teaching Notesmuhiastephen005Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 2 Different Perspectives About CurriculumDocument36 pagesLesson 2 Different Perspectives About CurriculumLecel MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature of CurriculumDocument56 pagesNature of CurriculumedionPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 27Document5 pagesModule 27Kel LumawanPas encore d'évaluation

- National Competency-Based Teacher StandardsDocument15 pagesNational Competency-Based Teacher StandardsDen SeguenzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument38 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentanilenePas encore d'évaluation

- The Curriculum Design ProcessDocument10 pagesThe Curriculum Design ProcessGerryCastillanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 EuDocument37 pagesModule 2 EuRhea Tamayo CasuncadPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum PlanningDocument41 pagesCurriculum PlanningLOLITA GALAMITONPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophical Perspectives in TeacherDocument12 pagesPhilosophical Perspectives in TeacherDexter GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophical Perspectives in TeacherDocument12 pagesPhilosophical Perspectives in TeacherDexter GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Approaches To School CurriculmDocument7 pagesApproaches To School CurriculmJonelle Joy TubisPas encore d'évaluation

- Connected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeD'EverandConnected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeTricia A. FerrettPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To CurriculumDocument54 pagesIntroduction To Curriculumsatiyavani darmalingam0% (1)

- The Classical Homeschooling Handbook: A Parents Guide To Traditional Christian EducationD'EverandThe Classical Homeschooling Handbook: A Parents Guide To Traditional Christian EducationPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum DevDocument29 pagesCurriculum DevWen PamanilayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning In and Across the DisciplinesD'EverandThe Scholarship of Teaching and Learning In and Across the DisciplinesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- 5.0 Summary and Overview: Chapter 5: The Curriculum of Teacher EducationDocument18 pages5.0 Summary and Overview: Chapter 5: The Curriculum of Teacher EducationJun YoutubePas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2Document18 pagesModule 2CHERRY MAE ALVARICO100% (1)

- The Teacher and The School Curriculum Manuscript Final EditedDocument116 pagesThe Teacher and The School Curriculum Manuscript Final EditedClaire RedfieldPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Concepts Nature and Purposes PDFDocument76 pagesCurriculum Concepts Nature and Purposes PDFJofen Ann Hisoler Tangpuz100% (2)

- Teaching Philosophy of Science To ScientistsDocument23 pagesTeaching Philosophy of Science To ScientistsAsim RazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Definisi KurikulumDocument21 pagesDefinisi KurikulumM Agung JazulliPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning to be Learners: A Mathegenical Approach to Theological EducationD'EverandLearning to be Learners: A Mathegenical Approach to Theological EducationPas encore d'évaluation

- M2 - Lesson 1 The School CurriculumDocument7 pagesM2 - Lesson 1 The School CurriculumJirk Jackson Esparcia89% (19)

- Lecture Notes in Curriculum DevelopmentDocument15 pagesLecture Notes in Curriculum DevelopmentJerid Aisen Fragio85% (13)

- Week 3-Tals: 1. The Student Learning MovementDocument5 pagesWeek 3-Tals: 1. The Student Learning MovementPrincess PaulePas encore d'évaluation

- Edsci Ni EdDocument20 pagesEdsci Ni EdKimberly Ferrerr Belisario TabaquiraoPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 Lesson 1Document4 pagesModule 2 Lesson 1Hector PonferradaPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Curriculum Operating in SchoolsDocument25 pagesTypes of Curriculum Operating in SchoolsJanna Gomez100% (1)

- Philosophical Foundation of Curriculum DevelopmentDocument12 pagesPhilosophical Foundation of Curriculum DevelopmentRuben Jr RestificarPas encore d'évaluation

- MED5 Written Report PangGroupDocument5 pagesMED5 Written Report PangGroupRowelyn SisonPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 - The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumDocument10 pagesModule 2 - The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumVannessa LacsamanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Disciplines and SubjectsDocument163 pagesUnderstanding Disciplines and Subjectsabhishek rana100% (1)

- MODULE 2 LESSON 1 The School Curriculum Definition, Nature and ScopeDocument6 pagesMODULE 2 LESSON 1 The School Curriculum Definition, Nature and Scopeprincess pauline laiz0% (2)

- Curriculum: Concepts, Nature and Purposes: in A Narrow Sense: Curriculum Is Viewed Merely As Listing ofDocument42 pagesCurriculum: Concepts, Nature and Purposes: in A Narrow Sense: Curriculum Is Viewed Merely As Listing ofVan Errl Nicolai Santos100% (1)

- Curriculum Development: Presented By: Marvelyn Fuggan ManeclangDocument98 pagesCurriculum Development: Presented By: Marvelyn Fuggan ManeclangMarvelyn Maneclang Catubag83% (18)

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument27 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentAngie Bern LapizPas encore d'évaluation

- The Curriculum of Teacher EducationDocument18 pagesThe Curriculum of Teacher EducationFELOMINO LLACUNA JR.Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Reflection PaperDocument3 pages1st Reflection PaperPsalm BanuelosPas encore d'évaluation

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in General Physics I Time Frame: 60 MinutesDocument7 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in General Physics I Time Frame: 60 MinutesWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in Science (Grade 8 - 3 Quarter) Time Frame: 60 MinutesDocument7 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in Science (Grade 8 - 3 Quarter) Time Frame: 60 MinutesWayne David C. Padullon100% (5)

- 1st Summative Test (Stoichiometry)Document2 pages1st Summative Test (Stoichiometry)Wayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre-Test (Electromagnetic Spectrum)Document2 pagesPre-Test (Electromagnetic Spectrum)Wayne David C. Padullon100% (3)

- Post-Test (Electromagnetic Spectrum)Document2 pagesPost-Test (Electromagnetic Spectrum)Wayne David C. Padullon0% (1)

- Reflection Paper (WEBINAR #1)Document1 pageReflection Paper (WEBINAR #1)Wayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in Science (Grade 8 - 3 Quarter) Time Frame: 60 MinutesDocument7 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in Science (Grade 8 - 3 Quarter) Time Frame: 60 MinutesWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st PPT (Stoichiometry - Formula and Molecular Mass)Document38 pages1st PPT (Stoichiometry - Formula and Molecular Mass)Wayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Post-Test (Electromagnetic Spectrum)Document2 pagesPost-Test (Electromagnetic Spectrum)Wayne David C. Padullon0% (1)

- 3rd PPT (Stoichiometry - Percentage Composition of Compounds) No VidDocument8 pages3rd PPT (Stoichiometry - Percentage Composition of Compounds) No VidWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Written Report in Biochemistry (Lipids) : Submitted byDocument9 pagesWritten Report in Biochemistry (Lipids) : Submitted byWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- 4th PPT Stoichiometry Empirical and Molecular Formula No VidDocument14 pages4th PPT Stoichiometry Empirical and Molecular Formula No VidWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- C. Plan B One Step PillDocument2 pagesC. Plan B One Step PillWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz in Lipids (G1)Document3 pagesQuiz in Lipids (G1)Wayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 11 StarsDocument35 pagesChapter 11 StarsWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewer in Electricity and MagnetismDocument3 pagesReviewer in Electricity and MagnetismWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Teacher As A Curricularist: Learning Episode 1Document6 pagesThe Teacher As A Curricularist: Learning Episode 1Wayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

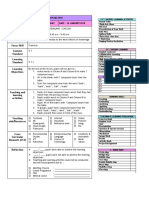

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG: I. ObjectivesDocument4 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG: I. ObjectivesWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- LifecyleofstarsDocument32 pagesLifecyleofstarsWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz in Lipids (G1)Document3 pagesQuiz in Lipids (G1)Wayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesReaction PaperWayne David C. Padullon67% (6)

- Life Cycle of A Star: Waves, Atoms and SpaceDocument40 pagesLife Cycle of A Star: Waves, Atoms and SpaceWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Mi Ultimo AdiosDocument2 pagesMi Ultimo AdiosWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- AlkynesDocument22 pagesAlkynesWayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- Girls: Participation (5%)Document6 pagesGirls: Participation (5%)Wayne David C. PadullonPas encore d'évaluation

- The-Psychology-of-Safety-Handbook-Scott Gueller PDFDocument560 pagesThe-Psychology-of-Safety-Handbook-Scott Gueller PDFmarkiu100% (3)

- Question and Answer IctDocument2 pagesQuestion and Answer IctHanaJuliaKristyPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan in Teaching English in The K To 12 CurriculumDocument4 pagesLesson Plan in Teaching English in The K To 12 CurriculumMark LaboPas encore d'évaluation

- Waqar cv1Document3 pagesWaqar cv1Qasim MunawarPas encore d'évaluation

- Shapes and Shadows PDFDocument3 pagesShapes and Shadows PDFprabhuPas encore d'évaluation

- College of Education EDUC 122 April 14, 2014 Integrative Teaching Strategies S.Y. 2014-2015 1 UnitDocument5 pagesCollege of Education EDUC 122 April 14, 2014 Integrative Teaching Strategies S.Y. 2014-2015 1 UnitZypherMeshPas encore d'évaluation

- 2019 Division Als Festival of Skills and TalentsDocument9 pages2019 Division Als Festival of Skills and TalentsAlanie Grace Beron TrigoPas encore d'évaluation

- Swahili EnglishDocument250 pagesSwahili EnglishNJEBARIKANUYE Eugène100% (1)

- Divided We Fail: Coming Together Through Public School Choice: The Report of The Century Foundation Working Group On State Implementation of Election ReformDocument68 pagesDivided We Fail: Coming Together Through Public School Choice: The Report of The Century Foundation Working Group On State Implementation of Election ReformTCFdotorgPas encore d'évaluation

- Zahra Asghar Ali CVDocument3 pagesZahra Asghar Ali CVZahraAsgharAliPas encore d'évaluation

- Allison Blake ResumeDocument1 pageAllison Blake Resumeapi-380141609Pas encore d'évaluation

- Recommendation SampleDocument2 pagesRecommendation SampleAyaBasilioPas encore d'évaluation

- Scholastic Triumphs at Ateneo de Manila (1872-1877)Document34 pagesScholastic Triumphs at Ateneo de Manila (1872-1877)Julie Ann Obina100% (3)

- Risk Assessment 2Document3 pagesRisk Assessment 2chris_friskeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Choice Theory Ppt-Absolute FinalDocument24 pagesChoice Theory Ppt-Absolute Finalapi-280470673Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cult ChangeinmindanaoDocument256 pagesCult ChangeinmindanaoRicardo Veloz100% (1)

- Aesthetic Confusion - The Legacy of New CriticismDocument7 pagesAesthetic Confusion - The Legacy of New CriticismTM Fazar .IzzamuddinPas encore d'évaluation

- Empirical EvidenceDocument10 pagesEmpirical EvidenceStephenPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Management Notes and ReviewerDocument4 pagesFinancial Management Notes and ReviewerEzio Paulino100% (1)

- 344fall 07syllabusDocument1 page344fall 07syllabusapi-3808925Pas encore d'évaluation

- World03 02 16Document40 pagesWorld03 02 16The WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Innovation and Innovative ManagementDocument504 pagesInclusive Innovation and Innovative ManagementThan Nguyen100% (2)

- An Open To Letter To Florida's GovernorDocument2 pagesAn Open To Letter To Florida's GovernorActionNewsJaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan 3Document3 pagesLesson Plan 3api-295499931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Institute Name: Indian Institute of Science (IR-O-U-0220)Document3 pagesInstitute Name: Indian Institute of Science (IR-O-U-0220)Aashutosh PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Leave of Absence Form: InstructionsDocument2 pagesLeave of Absence Form: InstructionsCharo GironellaPas encore d'évaluation

- ASTD ModelDocument4 pagesASTD ModelRobin Neema100% (1)

- Blair Mod 15 Operant Teacher ResourcesDocument32 pagesBlair Mod 15 Operant Teacher ResourcesJanie VandeBergPas encore d'évaluation

- Can Anyone Plan A Quality Physical Education Program?: A Q&A Session With Dr. David ChorneyDocument4 pagesCan Anyone Plan A Quality Physical Education Program?: A Q&A Session With Dr. David ChorneyAbu Umar Al FayyadhPas encore d'évaluation

- Week: 3 Class / Subject Time Topic/Theme Focus Skill Content Standard Learning Standard Learning ObjectivesDocument9 pagesWeek: 3 Class / Subject Time Topic/Theme Focus Skill Content Standard Learning Standard Learning ObjectivesAlya FarhanaPas encore d'évaluation