Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Standard Chartered Bank Employees Union vs. Confessor (Digest)

Transféré par

Dom Robinson BaggayanTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Standard Chartered Bank Employees Union vs. Confessor (Digest)

Transféré par

Dom Robinson BaggayanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Standard Chartered Bank Employees Union vs Confessor

Facts:

Bank and the Union signed a five-year collective bargaining agreement (CBA)

with a provision to renegotiate the terms thereof on the third year. Prior to

the expiration of the three-year period but within the sixty-day freedom

period, the Union initiated the negotiations. On February 18, 1993, the Union,

through its President, Eddie L. Divinagracia, sent a letter containing its

proposals covering political provisions and thirty-four (34) economic

provisions. The Bank attached its counter-proposal to the non-economic

provisions proposed by the Union. The Bank posited that it would be in a

better position to present its counter-proposals on the economic items after

the Union had presented its justifications for the economic proposals.

Before the commencement of the negotiation, the Union, through

Divinagracia, suggested to the Bank’s Human Resource Manager and head of

the negotiating panel, Cielito Diokno, that the bank lawyers should be

excluded from the negotiating team. The Bank acceded. Meanwhile, Diokno

suggested to Divinagracia that Jose P. Umali, Jr., the President of the National

Union of Bank Employees (NUBE), the federation to which the Union was

affiliated, be excluded from the Union’s negotiating panel. However, Umali

was retained as a member thereof.

Except for the provisions on signing bonus and uniforms, the Union and the

Bank failed to agree on the remaining economic provisions of the CBA. The

Union declared a deadlock. On the other hand, the Bank filed a complaint for

Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) and Damages before the Arbitration Branch of the

National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) in Manila. It contended that the

Union demanded "sky high economic demands," indicative of blue-sky

bargaining. Further, the Union violated its no strike- no lockout clause by

filing a notice of strike before the NCMB. Considering that the filing of notice

of strike was an illegal act, the Union officers should be dismissed.

Issue: Whether or not the Union was able to substantiate its claim of unfair

labor practice against the Bank arising from the latter’s alleged

“interference” with its choice of negotiator; surface bargaining; making bad

faith non-economic proposals; and refusal to furnish the Union with copies of

the relevant data;

Ruling: ART. 243. COVERAGE AND EMPLOYEES’ RIGHT TO SELF-

ORGANIZATION. – All persons employed in commercial, industrial and

agricultural enterprises and in religious, charitable, medical or educational

institutions whether operating for profit or not, shall have the right to self-

organization and to form, join, or assist labor organizations of their own

choosing for purposes of collective bargaining. Ambulant, intermittent and

itinerant workers, self-employed people, rural workers and those without any

definite employers may form labor organizations for their mutual aid and

protection.

Article 248(a) of the Labor Code, considers it an unfair labor practice when

an employer interferes, restrains or coerces employees in the exercise of

their right to self-organization or the right to form association. The right to

self-organization necessarily includes the right to collective bargaining.

Parenthetically, if an employer interferes in the selection of its negotiators or

coerces the Union to exclude from its panel of negotiators a representative of

the Union, and if it can be inferred that the employer adopted the said act to

yield adverse effects on the free exercise to right to self-organization or on

the right to collective bargaining of the employees, ULP under Article 248(a)

in connection with Article 243 of the Labor Code is committed. In order to

show that the employer committed ULP under the Labor Code, substantial

evidence is required to support the claim. Substantial evidence has been

defined as such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as

adequate to support a conclusion.

The circumstances that occurred during the negotiation do not show that the

suggestion made by Diokno to Divinagracia is an anti-union conduct from

which it can be inferred that the Bank consciously adopted such act to yield

adverse effects on the free exercise of the right to self-organization and

collective bargaining of the employees, especially considering that such was

undertaken previous to the commencement of the negotiation and

simultaneously with Divinagracia’s suggestion that the bank lawyers be

excluded from its negotiating panel. It is clear that such ULP charge was

merely an afterthought. The accusation occurred after the arguments and

differences over the economic provisions became heated and the parties had

become frustrated.

The Duty to Bargain Collectively

Surface bargaining is defined as “going through the motions of negotiating”

without any legal intent to reach an agreement. The Union has not been able

to show that the Bank had done acts, both at and away from the bargaining

table, which tend to show that it did not want to reach an agreement with

the Union or to settle the differences between it and the Union. Admittedly,

the parties were not able to agree and reached a deadlock. However, it is

herein emphasized that the duty to bargain “does not compel either party to

agree to a proposal or require the making of a concession. Hence, the

parties’ failure to agree did not amount to ULP under Article 248(g) for

violation of the duty to bargain.

Estoppel not Applicable In the Case at Bar

The approval of the CBA and the release of signing bonus do not necessarily

mean that the Union waived its ULP claim against the Bank during the past

negotiations. After all, the conclusion of the CBA was included in the order of

the SOLE, while the signing bonus was included in the CBA itself.

The Union Did Not Engage In Blue-Sky Bargaining

The Bank failed to show that the economic demands made by

the Union were exaggerated or unreasonable. The minutes of the meeting

show that the Union based its economic proposals on data of rank and file

employees and the prevailing economic benefits received by bank

employees from other foreign banks doing business in the Philippines and

other branches of the Bank in the Asian region.

In sum, we find that the public respondent did not act with grave abuse of

discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction when it issued the

questioned order and resolutions. While the approval of the CBA and the

release of the signing bonus did not estop the Union from pursuing its claims

of ULP against the Bank, we find that the latter did not engage in ULP. We,

likewise, hold that the Union is not guilty of ULP.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Gurudas Treason TheNewWorldOrder 1996Document318 pagesGurudas Treason TheNewWorldOrder 1996larsrordam100% (3)

- Criminal Law I Midterm ExamDocument5 pagesCriminal Law I Midterm ExamKRISTIAN DAVE VILLAPas encore d'évaluation

- Cecilia Manese v. Jollibee Foods Corp.Document3 pagesCecilia Manese v. Jollibee Foods Corp.Anonymous CjcsgVvzPas encore d'évaluation

- Union-University dispute over CBA interpretation and grievance proceduresDocument1 pageUnion-University dispute over CBA interpretation and grievance proceduresJulius Geoffrey TangonanPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 - Standard Chartered Employees v. Confesor - JavierDocument2 pages10 - Standard Chartered Employees v. Confesor - JavierNica Cielo B. LibunaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Rosario Bros vs. Ople Case DigestDocument1 pageRosario Bros vs. Ople Case Digestunbeatable38Pas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Secularity and SecularismDocument13 pagesContemporary Secularity and SecularismInstitute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture100% (1)

- HOLIDAY INN MANILA v. NLRCDocument2 pagesHOLIDAY INN MANILA v. NLRCrobbyPas encore d'évaluation

- Belgica V Ochoa IIDocument3 pagesBelgica V Ochoa IIBai Johara Sinsuat100% (1)

- Labor Law Digested CasesDocument13 pagesLabor Law Digested CasesLyle MarcoPas encore d'évaluation

- LaborDocument141 pagesLaborGian Paula MonghitPas encore d'évaluation

- STANDARD CHARTERED BANK EMPLOYEES UNION VsDocument2 pagesSTANDARD CHARTERED BANK EMPLOYEES UNION VsZyrene Cabaldo100% (2)

- SILVALA - Labor Law II PDFDocument20 pagesSILVALA - Labor Law II PDFMaricris SilvalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Suntay V Suntay - Spec ProDocument1 pageSuntay V Suntay - Spec Procarlie lopezPas encore d'évaluation

- ST Lukes Vs SanchezDocument3 pagesST Lukes Vs SanchezHarold EstacioPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic Planters v. Laguesma DigestDocument5 pagesRepublic Planters v. Laguesma DigestJake AriñoPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 131374Document12 pagesG.R. No. 131374Paul PsyPas encore d'évaluation

- Crimpro Rule 113 and 114Document4 pagesCrimpro Rule 113 and 114Jen MoloPas encore d'évaluation

- BS Savings V SiaDocument5 pagesBS Savings V SiaYoo Si JinPas encore d'évaluation

- BPI Employees Union-Davao v. BPI, July 24, 2013Document2 pagesBPI Employees Union-Davao v. BPI, July 24, 2013bernadeth ranolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Accessory penalties for crimes in the PhilippinesDocument1 pageAccessory penalties for crimes in the PhilippinesMonalizts D.Pas encore d'évaluation

- PNB Vs PNB Employees Assn, 115 SCRA 507Document3 pagesPNB Vs PNB Employees Assn, 115 SCRA 507Ronel Jeervee MayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sumifru (Philippines) Corp v. Nagkahiusang Mamumuo Sa Suyapa Farm G.R. No. 202091Document3 pagesSumifru (Philippines) Corp v. Nagkahiusang Mamumuo Sa Suyapa Farm G.R. No. 202091CHARMILLI N POTESTASPas encore d'évaluation

- Philacor v. LaguesmaDocument2 pagesPhilacor v. LaguesmaKaren Patricio Lustica100% (1)

- #163 San Miguel Corp Supervisors and Exempt Union vs. Hon. LaguesmaDocument2 pages#163 San Miguel Corp Supervisors and Exempt Union vs. Hon. LaguesmarossiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Religious Aspects of La ViolenciaDocument25 pagesReligious Aspects of La ViolenciaDavidPas encore d'évaluation

- San Miguel Corporation Employees Union vs. BersamiraDocument3 pagesSan Miguel Corporation Employees Union vs. Bersamiravanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aguilar Corp. V NLRCDocument2 pagesAguilar Corp. V NLRCloricaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Marxist Literary TheoryDocument3 pagesMarxist Literary TheoryChoco Mallow100% (2)

- 34 Meralco V SOLEDocument1 page34 Meralco V SOLEJet SiangPas encore d'évaluation

- Pagkakaisa NG Mga Manggagawa Sa Triumph International vs. Ferrer-Calleja, G. R. No. 85915, Jan. 17, 1990Document9 pagesPagkakaisa NG Mga Manggagawa Sa Triumph International vs. Ferrer-Calleja, G. R. No. 85915, Jan. 17, 1990Kylie Kaur Manalon DadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor Rights and Security of TenureDocument10 pagesLabor Rights and Security of TenureSandy CelinePas encore d'évaluation

- National Development Co. v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesNational Development Co. v. Court of AppealsNoreenesse SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Vicente S. Almario v. Philippine Airlines, Inc. G.R. No. 170928Document2 pagesVicente S. Almario v. Philippine Airlines, Inc. G.R. No. 170928Ellis LagascaPas encore d'évaluation

- BMG Records and Yap v. AparecioDocument4 pagesBMG Records and Yap v. AparecioChimney sweepPas encore d'évaluation

- INC Shipmanagement v. Camporedondo (2015)Document1 pageINC Shipmanagement v. Camporedondo (2015)Nori LolaPas encore d'évaluation

- VILLAMARIA VS CA: Jeepney driver's illegal dismissal caseDocument5 pagesVILLAMARIA VS CA: Jeepney driver's illegal dismissal casejohneurickPas encore d'évaluation

- USAEU vs. CADocument2 pagesUSAEU vs. CAJanlo FevidalPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Terminals Inc Vs VillanuevaDocument2 pagesAsian Terminals Inc Vs VillanuevaakosibatmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Standard Chatered Bank Employees Union (NUBE) vs. Hon. Nieves Confesor, June 16, 2004Document3 pagesStandard Chatered Bank Employees Union (NUBE) vs. Hon. Nieves Confesor, June 16, 2004Raje Paul ArtuzPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 People vs. HernandezDocument1 page11 People vs. HernandezAko Si Paula MonghitPas encore d'évaluation

- Emilio M. CaparosoDocument1 pageEmilio M. CaparosoRuiz Arenas AgacitaPas encore d'évaluation

- 74 Automotive Engine Rebuilders Vs UNYONDocument3 pages74 Automotive Engine Rebuilders Vs UNYONJet SiangPas encore d'évaluation

- Lakas Indiustriya vs. Burlingame (2007)Document4 pagesLakas Indiustriya vs. Burlingame (2007)Xavier BataanPas encore d'évaluation

- GERIZAL Summative Assessment Aralin 3 - GROUP 4Document5 pagesGERIZAL Summative Assessment Aralin 3 - GROUP 4Jan Gavin GoPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor Digests - Final Set 7Document3 pagesLabor Digests - Final Set 7ResIpsa LoquitorPas encore d'évaluation

- Woodchild Holdings Inc. v. Roxas Electric and Construction Co., Inc.Document17 pagesWoodchild Holdings Inc. v. Roxas Electric and Construction Co., Inc.maggyganPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Pepsi Cola v. Mun. of TanauanDocument17 pages3 Pepsi Cola v. Mun. of TanauanMlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Homestead land exemption from CARP coverageDocument2 pagesHomestead land exemption from CARP coverageLaw2019upto2024Pas encore d'évaluation

- Samahang Manggagawa Sa PREMEX V Sec of Labor 1st CaseDocument1 pageSamahang Manggagawa Sa PREMEX V Sec of Labor 1st CaseGnPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Scholastica's College Vs TorresDocument5 pagesSt. Scholastica's College Vs TorresMaricar Corina CanayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Francisco vs NLRC ruling on employer-employee relationshipDocument2 pagesFrancisco vs NLRC ruling on employer-employee relationshipRosana Villordon SolitePas encore d'évaluation

- 6 - Conde Vs Abaya (D)Document2 pages6 - Conde Vs Abaya (D)Angelic ArcherPas encore d'évaluation

- MaquilingDocument2 pagesMaquilingAish Nichole Fang Isidro100% (1)

- Royale Homes Marketing Corp. v. AlcantaraDocument2 pagesRoyale Homes Marketing Corp. v. Alcantaraanne6louise6panagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Regular vs Pakyaw Workers in Poultry FarmingDocument3 pagesRegular vs Pakyaw Workers in Poultry FarmingchrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Devoma, San Beda University Manila, Personal DigestsDocument2 pagesDevoma, San Beda University Manila, Personal DigestsKimsey Clyde DevomaPas encore d'évaluation

- (G.R. No. 106518. March 11, 1999.) Abs-Cbn Supervisors Employees Union Members, V. Abs-Cbn Broadcasting CorpDocument10 pages(G.R. No. 106518. March 11, 1999.) Abs-Cbn Supervisors Employees Union Members, V. Abs-Cbn Broadcasting CorpKaisser John Pura AcuñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Brotherhood Labor Unity Movement v. ZamoraDocument13 pagesBrotherhood Labor Unity Movement v. ZamoraAngelo Raphael B. DelmundoPas encore d'évaluation

- Holcim Philippines Inc vs. ObraDocument2 pagesHolcim Philippines Inc vs. Obrakong pagulayanPas encore d'évaluation

- PNOC Dockyard Vs NLRCDocument6 pagesPNOC Dockyard Vs NLRCJohnday MartirezPas encore d'évaluation

- Tabas v. California Manufacturing Company Inc.: Employer-Employee Relationship FoundDocument6 pagesTabas v. California Manufacturing Company Inc.: Employer-Employee Relationship FoundJesse Myl MarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Reviewing Constitutionality of Religious Exemption from Forced Union MembershipDocument15 pagesCase Reviewing Constitutionality of Religious Exemption from Forced Union MembershipMary Ann BernaldezPas encore d'évaluation

- San Miguel Corp. Employees Union-PTGWO vs. BersamiraDocument11 pagesSan Miguel Corp. Employees Union-PTGWO vs. BersamirajokuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Security Bank Savings Corporation vs. SingsonDocument2 pagesSecurity Bank Savings Corporation vs. Singsonanne6louise6panagaPas encore d'évaluation

- San Miguel Corporation Vs NLRCDocument1 pageSan Miguel Corporation Vs NLRCRolan Klyde Kho YapPas encore d'évaluation

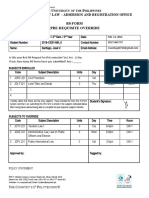

- R0 Form (Pre-Requisite Override Form) : P U P College of Law - Admission and Registration OfficeDocument2 pagesR0 Form (Pre-Requisite Override Form) : P U P College of Law - Admission and Registration OfficeYeeun JangPas encore d'évaluation

- Innodata Philippines, Inc. v. Quejada (1) Lopez G.R. No. 162839 (2006)Document2 pagesInnodata Philippines, Inc. v. Quejada (1) Lopez G.R. No. 162839 (2006)Alia Arnz-DragonPas encore d'évaluation

- Not guilty of ULPDocument44 pagesNot guilty of ULPdave_88opPas encore d'évaluation

- INOCENCIO ROSETE vs. Auditor General (Special Agent)Document2 pagesINOCENCIO ROSETE vs. Auditor General (Special Agent)Dom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Nazareno Vs CaDocument6 pagesNazareno Vs CaCristina Pattaguan TaccadPas encore d'évaluation

- Yamada vs. Manila Railroad Co.Document16 pagesYamada vs. Manila Railroad Co.Dom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- INOCENCIO ROSETE vs. Auditor General (Special Agent)Document2 pagesINOCENCIO ROSETE vs. Auditor General (Special Agent)Dom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Narra Nickel Vs Redmont 195580Document22 pagesNarra Nickel Vs Redmont 195580John Jeric LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Bona Fide Occupational Qualification (Star Paper Corp, Glaxowellcome)Document1 pageBona Fide Occupational Qualification (Star Paper Corp, Glaxowellcome)Dom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- 1Document1 page1Dom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- First time at the Hall of Justice for IBP internship dutiesDocument2 pagesFirst time at the Hall of Justice for IBP internship dutiesDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Monetary Claim Rodriguez vs. Park and RideDocument1 pageMonetary Claim Rodriguez vs. Park and RideDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Finals Cases LegislativeDocument40 pagesFinals Cases LegislativeDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- National Union Fire Insurancevs StolDocument4 pagesNational Union Fire Insurancevs StolLove HatredPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court declares Pork Barrel System unconstitutionalDocument3 pagesSupreme Court declares Pork Barrel System unconstitutionalDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- 1-UTAK Vs COMELECDocument12 pages1-UTAK Vs COMELECRean Raphaelle GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Full Text of SC Ruling On EDCADocument118 pagesFull Text of SC Ruling On EDCAGMA News OnlinePas encore d'évaluation

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue Vs Algue, Inc.Document4 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue Vs Algue, Inc.Elaine ChescaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ilo Convention No. 87Document5 pagesIlo Convention No. 87Nikko Franchello SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- SCB Employees Union vs Bank unfair labor practice claimsDocument3 pagesSCB Employees Union vs Bank unfair labor practice claimsDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- OkDocument12 pagesOkDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Balgos & Perez Law Office For Private Respondent in Both CasesDocument9 pagesBalgos & Perez Law Office For Private Respondent in Both CasesDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sogod Vs Rosal Case DigestDocument2 pagesSogod Vs Rosal Case DigestAllen OlayvarPas encore d'évaluation

- OkDocument1 pageOkDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- SCB Employees Union vs Bank unfair labor practice claimsDocument3 pagesSCB Employees Union vs Bank unfair labor practice claimsDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- OkDocument1 pageOkDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter III Foreign Activities Prohibition Against Aliens ExceptionsDocument1 pageChapter III Foreign Activities Prohibition Against Aliens ExceptionsDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic Planters vs. LaguesmaDocument5 pagesRepublic Planters vs. LaguesmaDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic Planters vs. LaguesmaDocument5 pagesRepublic Planters vs. LaguesmaDom Robinson BaggayanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Carpet WeaverDocument2 pagesThe Carpet WeaverRashmeet KaurPas encore d'évaluation

- HR Assistant Manager OpeningDocument6 pagesHR Assistant Manager OpeningPraneet TPas encore d'évaluation

- Bhutan ConstitutionDocument40 pagesBhutan ConstitutionChris ChiangPas encore d'évaluation

- PHD Report Notes-OligarchyDocument7 pagesPHD Report Notes-OligarchyChristian Dave Tad-awanPas encore d'évaluation

- Tool 3 - Social Inclusion Assessment 0909Document6 pagesTool 3 - Social Inclusion Assessment 0909bbking44Pas encore d'évaluation

- POB Ch08Document28 pagesPOB Ch08Anjum MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Youth Pledge Day Marks Birth of Indonesian NationDocument6 pagesYouth Pledge Day Marks Birth of Indonesian NationisnadewayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- List of MinistersDocument16 pagesList of MinistersNagma SuaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Bitter Olives - E1Document1 pageBitter Olives - E1Matan LureyPas encore d'évaluation

- CWOPA Slry News 20110515 3500StateEmployeesEarnMoreThan100kDocument90 pagesCWOPA Slry News 20110515 3500StateEmployeesEarnMoreThan100kEHPas encore d'évaluation

- McAdams Poll MemoDocument2 pagesMcAdams Poll MemoHannah MichellePas encore d'évaluation

- Korean War Neoliberalism and ConstructivismDocument6 pagesKorean War Neoliberalism and ConstructivismTomPas encore d'évaluation

- SK Reso For Appointment of SK SecretaryDocument3 pagesSK Reso For Appointment of SK SecretaryTAU GOLDEN HARVESTPas encore d'évaluation

- The Journals of Charlotte Forten GrimkeDocument2 pagesThe Journals of Charlotte Forten GrimkeJim BeggsPas encore d'évaluation

- BlackbirdingDocument10 pagesBlackbirdingVanessa0% (1)

- Politics Disadvantage - Internal Links - HSS 2013Document103 pagesPolitics Disadvantage - Internal Links - HSS 2013Eric GuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Class Program For Grade Ii-Melchora Aquino: Masalipit Elementary SchoolDocument2 pagesClass Program For Grade Ii-Melchora Aquino: Masalipit Elementary SchoolJenalyn Labuac MendezPas encore d'évaluation

- Protecting The Non-Combatant': Chivalry, Codes and The Just War TheoryDocument22 pagesProtecting The Non-Combatant': Chivalry, Codes and The Just War TheoryperegrinumPas encore d'évaluation

- Com - Res - 9661 Peitition For Accreditation For Political PartyDocument11 pagesCom - Res - 9661 Peitition For Accreditation For Political PartyAzceril AustriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Visa ApplicationDocument2 pagesVisa ApplicationjhwimalarathnePas encore d'évaluation

- Lexington GOP Elects Chair Who Denies 2020 Election Results - The StateDocument9 pagesLexington GOP Elects Chair Who Denies 2020 Election Results - The Staterepmgreen5709Pas encore d'évaluation

- Labour Law Strikes and LockoutsDocument7 pagesLabour Law Strikes and LockoutsSantoshHsotnasPas encore d'évaluation

- No. Amendments Enforced Since Objectives: Amendments To The Constitution of IndiaDocument8 pagesNo. Amendments Enforced Since Objectives: Amendments To The Constitution of IndiaPrashant SuryawanshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Updated Davenport Community School District 2018-2019 Academic CalendarDocument1 pageUpdated Davenport Community School District 2018-2019 Academic CalendarMichelle O'NeillPas encore d'évaluation

- Wa'AnkaDocument367 pagesWa'AnkaAsarPas encore d'évaluation