Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

2 2

Transféré par

Margareth Bonita PasaribuTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

2 2

Transféré par

Margareth Bonita PasaribuDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Smart P., Maisonneuve H. and Polderman A.

(eds) Science Editors’ Handbook

European Association of Science Editors. www.ease.org.uk

2.2: Anatomical nomenclature

Jenny Gretton

The Old Thatched Lodge, Highcotts Lane, West Clandon, GU4 7XA, UK; jtgretton@btinternet.com

Until the 19th century, no attempt was made to formalize the Skeletal system – Systema skeletale

naming of the parts of the human body. In Western Europe, Table 2 lists some skeletal anatomical features by name,

anatomical structures were named in Greek or Latin or a followed by their plural and adjectival forms, etymology,

‘Latinized’ form of Greek. Body parts also acquired native- and some common combinations with other terms. Table 2

language names, many of which have remained in ‘official’ follows human anatomy from the head down, and lists only

use up to the present day. some of the major skeletal features.

In the last two centuries, various initiatives at national

and international levels have been made to produce a Muscular system – Systema musculare

formal nomenclature. As recently as 1996, associations The three kinds of muscular tissue are (a) cardiac, found

of anatomists throughout the world were asked to only in the heart, controlled by the autonomic (functioning

review a possible system and to produce translations involuntarily) nervous system; (b) striated (so-called

in their own languages. This initiative of the Federative ‘voluntary’), entirely dependent on its nerve supply from

Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT) resulted peripheral nerves and the central nervous system for

in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica in 1998.1 The normal activity; and (c) smooth or plain muscle innervated

naming of anatomical features now has a formal base, but (supplied) by the autonomic nervous system and therefore

the use of eponyms and abbreviations persists, with the unable to be controlled at will.

term used decided by the author and dictated by the target Table 3 lists some of the terms used to describe the

audience – the general public, practitioners or researchers. direction of movement and function of muscles. For

There are national and international publications that specific muscles and their functions a medical dictionary

provide a detailed system for anatomical nomenclature. for nurses may be helpful, as the explanations do not assume

This chapter is designed to help editors without medical a comprehensive knowledge of medical terminology.2,3

qualifications who may need points of reference when The names of muscles may describe their shape,

working in English and in an unfamiliar field. anatomical location and function. Their position and

The Latin terms for anatomical features follow the rules relative size and function may also form part of the names

for that language, the plural and adjectival forms taking of muscles or muscle groups, for example, lateralis (on

the appropriate endings from the ending of the noun form the outer side) and medialis (on the inner side). Relative

(see Table 2). Greek terms are transliterations or Latinized position is denoted as superior or inferior and in this

forms of the original, and most plural and adjectival context does not refer to the quality of tissue. Relative size

forms have become common through usage rather than is denoted as major or maximus (the larger) and minor

following the rules of grammar. Terms may be combined or minimus (the smaller), longus (the longer), brevis (the

for descriptive purposes, for example to describe a joint. shorter). By convention, muscles arise (have an origin) from

If an anatomical nomenclature for a non-English language bone or cartilage that is proximal (nearer to the trunk) to

is planned, the advice from the FCAT is that only Latin the insertion (insertio being Latin for attachment), which

terms should be used for creating a list; no attempt should may be fleshy or tendinous.

be made to use an English version as the basis for a non-

English nomenclature. Nervous system – Systema nervosum

As with the muscular system, the nerves are too numerous

Terms for position and relationship of features to list here. Again, a good dictionary for nurses will be

An author’s text will usually be easier to follow if the terms a help.2,3 The main divisions of the nervous system are

for the relationship and relative position of features are the central nervous system, consisting of the brain and

understood. This will also help in checking the orientation spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system, with

of illustrative material. Terms for position and relationship three components: the cranial, spinal and autonomic

assume that the human figure is standing, facing towards nerves. Cranial nerves arise from the brain and some

the observer, with the arms straight at the sides of the body have components of the autonomic system. Spinal nerves

and with the palms of the hands facing the observer. Table arise in pairs from each segment of the spinal cord. The

1 gives a list of terms for position and relationship, a short autonomic (involuntary) nerves control such functions as

description of their meaning, and examples of how they the digestive process.

might appear when used with other terms. A number of nerves are named for the musculoskeletal

feature or organ they innervate. In this case the adjectival

form is used, and the word ‘nerve’ usually follows, for

© The authors, 2013 Written 2002, revised 2013

2.2: Antomical nomenclature 2.2: Anatomical nomenclature

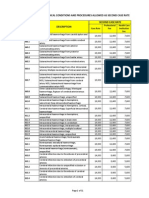

example ‘ulnar nerve’. Nerves are said to ‘branch’ and they is the Latin form; the English translation is artery, with Table 2. Skeletal anatomical terms in common usage, with their etymology (L: Latin; G: Greek), adjectival

can form a ‘plexus’ (Latin for plait). This arrangement the adjectival form arterial. Similarly, vena (plural venae) and plural forms

allows for certain nerve trunks to contain fibres from is the Latin form; the English translation is vein and the

different segments of the cord, for example lumbar plexus. adjectival form is venous. Noun Plural Adjective Etymology Combines asa

A single nerve may have a plexus of branches. The names Zygoma Zygomata or zygomas Zygomatic L/G

of some nerves combine position with the name of the Lymphatic system – Systema lymphoideum Maxilla Maxillae Maxillary L Maxillofacial

structure they supply. For example, the facial nerve supplies The lymphatic system consists of solid organs, such as the Mandibula Mandibulae Mandibular L

the muscles of the face, while the medial cutaneous nerves spleen, and numerous groups of lymph nodes that play an

supply the skin on the inner side. important part in the defences of the body. The names of Cervix Cervices Cervical L Cervico-thoracic

primary and secondary lymphoid organs usually include Clavicula Claviculae Clavicular L

Cardiovascular system – Systema cardiovascularae the name of the organ they serve. The names of lymphatic Acromion Acromia Acromial G Acromio-clavicular

The cardiovascular system consists of the heart and all the nodes may combine their anatomical relationship to

Scapula Scapulae or scapulas Scapular L

blood vessels. As with the muscular and nervous systems, another organ with their position in relation to other nodes.

the system of veins and arteries is complex and reference Humerus Humeri Humeral L Humero-

should be made to a medical or nurses’ dictionary. The major organs Sternum Sterna or sternums Sternal L/G Sterno-

The names of arteries and veins often include their The major organs are usually known by their non-Latin Vertebra Vertebrae Vertebral L

anatomical position and/or function as part of the or Greek names, for example heart or coeur or corazon,

nomenclature. For example, the arteria meningea media but there are Latin or Greek terms for them, and these are Ilium Ilia Iliac L Iliofemoral

is the middle artery of the brain, supplying the outer usually used for their adjectival forms (Table 4). Sacrum Sacra Sacral L Sacralgia or sacroiliac

meninges (covering of the brain). Arteria (plural arteriae) Coccyx Coccyges Coccygeal G

Pubis/ os pubis Pubises Pubic L Puboiliac

Table 1. Terms denoting anatomical positions and relationships. Terms used assume that the human figure is standing Ischium Ischia Ischial L/G Ischiopubic

facing the observer, with arms straight beside the body and palms of the hands turned towards the observer

Radius Radii Radial L Radioulnar

Term Position and relationship Example of usage Ulna Ulnae Ulnar L Usually follows: radioulnar

Lateral On outer side Lateral malleolus Carpus Carpi Carpal L/G Carpometa-carpal

Medial On middle or inner side Medial malleolus Metacarpal Metacarpi Metacarpal L/G Metacarpo-phalangeal

Coronal Vertical, side to side, ‘slice’ through body Coronal plane Phalange Phalanges Phalangeal G

Sagittal Anteroposterior median plane of body, or front-to-back ‘slice’ Sagittal plane Femur Femora Femoral L Femoroiliac

cutting body into right and left halves

Coxa Coxae Coxal L/G Coxalgia

Valgus Bent outwards Hallux valgus

Patella Patellae Patellar L Patello-femoral

Varus Bent inwards Genu varum

Tibia Tibiae Tibial L Tibio-femoral

Inter Between two anatomical features Intercostal

Fibula Fibulae Fibular L Usually follows; tibiofibular

Interstitial A space between closely packed tissues or cells Interstitial hernia

Malleolus Malleoli Malleolar L

Intra Within, enclosed by an anatomical feature Intramuscular

Tarsus Tarsi Tarsal G Tarso-metatarsal

Extra On the outside Extra-articular

Metatarsus Metatarsi Metatarsal G Metatarso-phalangeal

Peri Surrounding Periarticular

Proximal Nearest to the trunk Proximal phalanx a

Added terms are shown in italics.

Distal Furthest from trunk Distal phalanx

Anterior Front surface of body or limb; in front Anterior lobe Table 3. Terms associated with the direction of movement and function of muscles

Posterior Back surface of body or limb; behind Posterior chamber

Term Action Abbreviation Example of usagea

Superior Upper, nearest to top of head Superior gluteal vein

Abductor Moves away abd. Abductor digiti minimi

Inferior Lower, nearer to feet Inferior thyroid vein

Adductor Draws in, towards add. Adductor hallucis

Superficialis Near surface of skin or organ; superficial

Extensor Extends, straightens ext. Extensor hallucis longus

Profundus Remote from surface of skin or organ; deep

Flexor Flexes, bends flex. Flexor carpi radialis

Ipsilateral On same side of body Right leg, right arm

Pronator Turns face down pron. Pronator teres

Contralateral Opposite sides of body Right leg, left arm

Supinator Turns onto back, face up sup. Supinator

Tensor Tenses or stretches ten. Tensor fasciae latae

a

Added terms are shown in italics.

2 Science Editors’ Handbook Science Editors’ Handbook 3

2.2: Antomical nomenclature

Table 4. English names for major organs, with etymology, adjectival forms and possible combinations

Organ Greek/Latin (G/L) Adj. Combines asa

Brain Encephalon (G); also cerebrum (L) Encephalic; cerebral Encephalomyelitis; cerebrovascular

Heart Cor (L); also kardia Cordis; cardiac Basis cordis; cardiovascular

Lungs Pulmo (L) Pulmonary Pulmoaortic

Liver Hepar (G) Hepatic Hepatolenticular

Kidneys Nephros (G); also renum (L Nephritic; renal Nephrocardiac; renointestinal

a

Added terms are shown in italics.

Abbreviations and acronyms the name of the scientist or clinician who first reported or

Authors should be discouraged from using abbreviations observed a phenomenon may be used, and may be linked

by clear advice in the guide to authors of individual with a co-worker’s name, the geographical location, or even

journals. Where commonly used abbreviations are used the circumstances in which the observation was made. The

(for example, CVS for cardiovascular system) they should names of individuals and places (proper names) are written

always be given in full when first used. If the paper or with an initial capital; for example Auerbach’s plexus,

chapter is long, the terms should be explained again at the Bigelow’s ligament, Colles’ fracture. All proper names used

beginning of each new section. Abbreviations used in tables in English or Latin, whether used singly or in combination,

or graphics should be explained in the legend or caption, have an upper case initial letter; for example Achilles

not just in the text. Explanatory notes should be added if tendon or tendo Achilles.

the author has failed to do so, even if an abbreviation is in The use of eponyms is of some historical interest, but

common usage. For example CDH (congenital dislocation may not accurately denote the first observer. Eponyms may

of the hip) and DDH (developmental dislocation of the hip) also differ in different countries even though they describe

should be written in full at first mention, even though these the same thing, and they may give no indication of the

abbreviations are in common use. If an editor is creating function or structure being described. Most specialist

an in-house style book, a list of acceptable abbreviations journals prefer the use of scientific names for anatomical

and their full meanings within a specialty is very helpful structures, conditions, signs, and syndromes. In non-

to freelance or new in-house editorial staff. Excessive use scientific publications, such as newspapers, television and

of obscure abbreviations can lead to papers being rejected magazines, the use of eponyms is quite common. Over 400

on the grounds that the author(s) have not considered their eponyms are listed in the index of eponyms in Terminologia

readers (or editors!). Anatomica.1

Italics Diacritical marks and diphthongs

Those reading a medical manuscript for the first time may Diacritical marks and diphthongs are not used in most

be surprised by the apparently random use of italics. Your contemporary publications, but may appear in older

publication may have guidelines for their use. references. It is good practice for authors and editors

Italics can be used to highlight the names of certain to maintain these marks as they appear in the original

classes of item within the text, but anatomical features reference, so that a reference to a classic paper will be

given in Latin are sometimes italicized and follow the recognized by the most pedantic database search engine,

rule of being written in full the first time, for example and as a courtesy to those with diacritical marks in the

musculi fasciei (facial muscles) the first time, and m. fasciei spelling of their names. Diphthongs have fallen into disuse,

thereafter. for example: æ and œ are now written as ae and oe in

Manuscripts may have sections of text underlined, and Europe and as e in North American English. House style

this usually denotes the author’s wish to have that portion will dictate which form is used in publications.

of the text in italics when printed. With more sophisticated

word-processing packages the use of underlining to denote Acknowledgement

italics is disappearing, but the possibility still has to be I wish to acknowledge the help and encouragement given

borne in mind. by Professor Ruth E.M. Bowden, OBE, DSc, FRCS, who

Latin names that describe a process, or abnormal died on 19 December 2001.

condition, may also be in italics if that is a specific journal’s

house style: for example, hallux valgus (bunion), pes planus References

(flat foot) or coxa vara (decrease in angle of hip joint). 1 Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology. Terminologia

Anatomica. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag, 1998.

Upper case and eponyms 2 Royal College of Nursing Advisory Team. Dictionary of Nursing. 17th

Until the 20th century, there was no strict formality in International ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

anatomy and medicine for naming anatomical structures 3 McFerran A. Tanya (ed.) Minidictionary for Nurses. 6th ed. Oxford:

and their variants, or diseases and symptoms. Even today, Oxford University Press, 2011.

4 Science Editors’ Handbook

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- We Find Love: Daniel CaesarDocument2 pagesWe Find Love: Daniel CaesarMargareth Bonita PasaribuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Muni Long "Pain" (Live Performance) - Open MicDocument3 pagesMuni Long "Pain" (Live Performance) - Open MicMargareth Bonita PasaribuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Everything Has Changed Lyrics: and All I Feel in My Stomach Is Butterflies The Beautiful Kind, Making Up For Lost TimeDocument3 pagesEverything Has Changed Lyrics: and All I Feel in My Stomach Is Butterflies The Beautiful Kind, Making Up For Lost TimeMargareth Bonita PasaribuPas encore d'évaluation

- HoomanDocument6 pagesHoomanMargareth Bonita PasaribuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Central ner-WPS OfficeDocument2 pagesThe Central ner-WPS OfficeMargareth Bonita PasaribuPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Orthoprostheses FOR Congenital Lower Limb Longitudinal DeficienciesDocument36 pagesOrthoprostheses FOR Congenital Lower Limb Longitudinal DeficienciesAlfred JacksonPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Fasciocutaneous Flaps in Reconstruction of Lower Extremity OurDocument7 pagesFasciocutaneous Flaps in Reconstruction of Lower Extremity OurPraganesh VarshneyPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Veterinary Diagnostic Imaging, The Dog and Cat (Vetbooks - Ir) PDFDocument786 pagesVeterinary Diagnostic Imaging, The Dog and Cat (Vetbooks - Ir) PDFLeonardo A. Muñoz Dominguez100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Lowerlimb (LEG) : Chary Jaztine L. MangacopDocument15 pagesLowerlimb (LEG) : Chary Jaztine L. MangacopChary JaztinePas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Footwear Design Portfolio Skills Fashion Amp TextilesDocument193 pagesFootwear Design Portfolio Skills Fashion Amp TextilesReidaviqui Davilli94% (18)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Lower Limb - Anterior & Lateral Comp. of Leg - Dorsum of Foot-PostgraduateDocument56 pagesLower Limb - Anterior & Lateral Comp. of Leg - Dorsum of Foot-PostgraduateLaiba FaysalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Flash Cards - Bone MarkingsDocument12 pagesFlash Cards - Bone Markingssimone dumbrellPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Anatomy (Stockoe) For Mini NotesDocument86 pagesAnatomy (Stockoe) For Mini NotesIvy Dianne PascualPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Quadrimalleolar Fractures of The Ankle: Think 360°-A Step-By-Step Guide On Evaluation and FixationDocument3 pagesQuadrimalleolar Fractures of The Ankle: Think 360°-A Step-By-Step Guide On Evaluation and FixationFRANCISCOPas encore d'évaluation

- PhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 3 List of Medical Conditions and Procedures Allowed As Second Case RateDocument31 pagesPhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 3 List of Medical Conditions and Procedures Allowed As Second Case RateChrysanthus Herrera0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Veterinary AcupunctureDocument19 pagesVeterinary AcupuncturekinezildiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ankle FractureDocument11 pagesAnkle FracturecorsaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Ankle AnatomyDocument50 pagesAnkle AnatomyLiao WangPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- 1.1 Background: It Is Commonly Found That TheDocument14 pages1.1 Background: It Is Commonly Found That ThetorkPas encore d'évaluation

- Block 4 OPP Lecture NotesDocument59 pagesBlock 4 OPP Lecture Notesjeremy_raineyPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Subperiosteal Hematoma of The AnkleDocument2 pagesSubperiosteal Hematoma of The Ankleintan aryantiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Tibiofibular JointsDocument7 pagesThe Tibiofibular JointsVictor Espinosa BuendiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Blount's Disease (Textbook)Document17 pagesBlount's Disease (Textbook)Fadzhil AmranPas encore d'évaluation

- Posteriomedial Plating in Proximal TibiaDocument87 pagesPosteriomedial Plating in Proximal TibiaDr SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Case Study BkaDocument92 pagesCase Study BkaMaria CabangonPas encore d'évaluation

- AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long.17Document24 pagesAO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long.17LuisAngelPonceTorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Location of AppendigealDocument8 pagesLocation of Appendigealasa.99Pas encore d'évaluation

- LE Muscles OINADocument5 pagesLE Muscles OINAUshuaia Chely FilomenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Extremitas InferiorDocument26 pagesExtremitas InferiorummuhabibaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kellner Et Al. 2022 FaxinalipterusDocument32 pagesKellner Et Al. 2022 Faxinalipterusmauricio.garciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Buku-Anatomi Osteologi PDFDocument56 pagesBuku-Anatomi Osteologi PDFmuhammad firdausPas encore d'évaluation

- The Failed Hallux ValgusDocument127 pagesThe Failed Hallux ValgusFlorin MacariePas encore d'évaluation

- Foot and Ankle ANATOMY PDFDocument80 pagesFoot and Ankle ANATOMY PDFMark JayPas encore d'évaluation

- BJPS 1984 Cormack Classification of FlapsDocument8 pagesBJPS 1984 Cormack Classification of FlapsS EllurPas encore d'évaluation

- Below-Knee Amputation Surgery: Henry E. Loon, M.DDocument14 pagesBelow-Knee Amputation Surgery: Henry E. Loon, M.Ddinda salmahellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)