Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Reeves, Et Al., Nature, Jan 16, 2020.

Transféré par

Roxanne ReevesCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Reeves, Et Al., Nature, Jan 16, 2020.

Transféré par

Roxanne ReevesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Setting the agenda in research

Comment

Time for the Human

Screenome Project

Byron Reeves, Thomas Robinson & Nilam Ram

To understand how people screens or with platforms that are categorized

as ‘smartphone’, ’television’, ‘social media’,

use digital media, researchers ‘political news’ or ‘entertainment media’. Yet

need to move beyond screen today’s media experiences defy such simplis-

time and capture everything tic characterization: the range of content has

become too broad, patterns of consumption

we do and see on our screens. too fragmented1, information diets too idio-

syncratic2, experiences too interactive and

T

devices too mobile.

Policies and advice must be informed by

here has never been more anxiety accurate assessments of media use. These

about the effects of our love of should involve moment-by-moment cap-

screens — which now bombard us with ture of what people are doing and when,

social-media updates, news (real and and machine analysis of the content on their

fake), advertising and blue-spectrum screens and the order in which it appears.

light that could disrupt our sleep. Concerns are Technology now allows researchers to

growing about impacts on mental and physical record digital life in exquisite detail. And

health, education, relationships, even on pol- thanks to shifting norms around data sharing,

itics and democracy. Just last year, the World and the accumulation of experience and tools

Health Organization issued new guidelines in fields such as genomics, it is becoming eas-

about limiting children’s screen time; the ier to collect data while meeting expectations

US Congress investigated the influence of and legal requirements around data security

social media on political bias and voting; and and personal privacy.

California introduced a law (Assembly Bill 272) We call for a Human Screenome Project

that allows schools to restrict pupils’ use of — a collective effort to produce and analyse

smartphones. recordings of everything people see and do

All the concerns expressed and actions on their screens.

taken, including by scientists, legislators,

medical and public-health professionals and Screen time better or worse. But ‘time spent on Facebook’

advocacy groups, are based on the assump- According to a 2019 systematic review and could involve finding out what your friends

tion that digital media — in particular, social meta-analysis3, over the past 12 years, 226 stud- are doing, attending a business meeting,

media — have powerful and invariably negative ies have examined how media use is related to shopping, fundraising, reading a news arti-

effects on human behaviour. Yet so far, it has psychological well-being. These studies con- cle, bullying, even stalking someone. These

been a challenge for researchers to demon- sider mental-health problems such as anxiety, are vastly different activities that are likely to

strate empirically what seems obvious expe- depression and thoughts of suicide, as well have very different effects on a person’s health

rientially. Conversely, it has also been hard for as degrees of loneliness, life satisfaction and and behaviour.

them to demonstrate that such concerns are social integration. Another problem is that people are

misplaced. The meta-analysis found almost no unlikely to recollect exactly when they did

A major limitation of the thousands of systematic relationship between people’s what4,5. Recent studies that compared sur-

studies, carried out over the past decade or levels of exposure to digital media and their vey responses with computer logs of behav-

so, of the effects of digital media is that they do well-being. But almost all of these 226 stud- iour indicate that people both under- and

not analyse the types of data that could reveal ies used responses to interviews or question- over-report media exposure — often by as

exactly what people are seeing and doing on naires about how long people had spent on much as several hours per day6–8. In today’s

their screens — especially in relation to the social media, say, the previous day. complex media environment, survey ques-

problems that doctors, legislators and par- The expectation is that if someone reports tions about the past month or even the past

ents worry most about. Most use self-reports being on Facebook a lot, then somewhere day might be almost useless. How many times

of ‘screen time’. These are people’s own esti- among all those hours of screen time are the did you look at your phone yesterday?

mates of the time they spend engaging with ingredients that influence well-being, for The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) is

314 | Nature | Vol 577 | 16 January 2020

©

2

0

2

0

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

refined representations of actual use patterns.

A session begins when the screen lights up and

ends when it goes dark, and might last less than

a second if it entails checking the time. Or it

could start with a person responding to their

friend’s post on Facebook, and end an hour

later when they click on a link to read an article

about politics.

Measures of media use must also take

account of the scattering of content. Today’s

devices allow digital content that used to be

experienced as a whole (such as a film, news

story or personal conversation) to be atom-

ized, and the pieces viewed across several

sessions, hours or days. We need measures

that separate media use into content cate-

gories (political news, relationships, health

information, work productivity and so on) —

or, even better, weave dissimilar content into

sequences that might not make sense to others

but are meaningful for the user.

To try to capture more of the complexity,

some researchers have begun to use logging

software. This was developed predominantly

to provide marketers with information on what

websites people are viewing, where people are

located, or the time they spend using various

applications. Although these data can provide

more-detailed and -accurate pictures than

self-reports of total screen time, they don’t

reveal exactly what people are seeing and

doing at any given moment.

A better way

To record the moment-by-moment changes

on a person’s screen2,11, we have built a plat-

form called Screenomics. The software

A participant in a traditional Chinese opera competition plays on her phone. records, encrypts and transmits screenshots

automatically and unobtrusively every 5 sec-

currently spending US$300 million on a vast switch between platforms and between onds, whenever a device is turned on (see

THOMAS PETER/REUTERS

neuroimaging and child-development study, content within those? How do the moments go.nature.com/2fsy2j2). When it is deployed

eventually involving more than 10,000 chil- of engagement with various types of media on several devices at once, the screenshots

dren aged 9 and 10. Part of this investigates interact and evolve? In other words, academics from each one are synced in time.

whether media use influences brain and cog- need a multidimensional map of digital life. This approach differs from other attempts

nitive development. To indicate screen use, To illustrate, people tend to use their to track human–computer interactions — for

participants simply pick from a list of five laptops and smartphones in bursts of, on aver- instance, through the use of smartwatches and

standard time ranges, giving separate answers age, 10–20 seconds10. Metrics that quantify the fitness trackers, or diaries. It is more accurate,

for each media category and for weekdays and transitions people make between media seg- it follows use across platforms, and it samples

weekends. (The first report about media use ments within a session, and between media and more frequently. In fact, we are working on

from this study, published last year, showed the rest of life, would provide more temporally software that makes recordings every second.

a small or no relationship between media We have now collected more than 30 mil-

exposure and brain characteristics or cogni- “In today’s complex media lion screenshots — what we call ‘screenomes’

tive performance in computer-based tasks9.) — from more than 600 people. Even just two

environment, survey of these reveal what can be learnt from a fine-

Digital life questions about the past grained look at media use (see ‘Under the

Instead, researchers need to observe in month or even the past day microscope’ and All in the details’).

exquisite detail all the media that people This higher-resolution insight into media

engage with, the platforms they use and the

might be almost useless .” use could help answer long-held questions

content they see and create. How do they and lead to new ones. It might turn out, for

Nature | Vol 577 | 16 January 2020 | 315

©

2

0

2

0

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

Comment

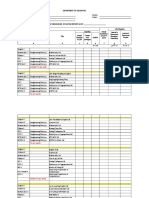

UNDER THE MICROSCOPE

perceived as more trustworthy than the same

indicating issues with attentional control, news obtained independently, for example.)

or perhaps reflecting an ability to process How can researchers get access to such

Recordings of smartphone use by two information faster. high-resolution data? And how can they

14-year-olds living in the same northern extract meaning from data sets comprising

California community reveal what can be Interactivity. Both adolescents spent time millions of screenshots?

learnt from a fine-grained analysis of media creating content as well as consuming One option is for investigators to collab-

use (see ‘All in the details’). it. They wrote text messages, recorded orate with the companies that own the data,

photos and videos, entered search terms and that have already developed sophisti-

Dose. A typical question that researchers and so on. On a questionnaire, both might cated ways to monitor people’s digital lives,

might ask is whether study participants have reported that they posted original at least in certain domains, such as Google,

are ‘heavy’ or ‘light’ phone users. Both material ‘sometimes’ or maybe ‘often’. But Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft. The

adolescents might have characterized their the screenshot data reflect patterns of Social Science One programme, established

phone use as ‘substantial’ had they been interactivity that would be almost impossible in 2018 at Harvard University in Cambridge,

asked the usual survey questions. Both for them to recall accurately. Massachusetts, involves academics part-

might have reported that they used their Participant A spent 2.6% of their screen nering with companies for exactly this pur-

smartphones ‘every day’ for ‘2 or more hours’ time in production mode, creating content pose12. Researchers can request to use certain

each day, and that looking at their phones evenly throughout the day and usually within anonymized Facebook data to study social

was the first thing they did each morning and social-media apps. By contrast, participant B media and democracy, for example.

the last thing they did every night. spent 7% of their total screen time producing Largely because of fears about data leaks

But detailed recordings of their actual content (and produced 2.5 times more). or study findings that might adversely affect

phone use over 3 weeks in 2018 highlight But they did so mainly in the evening while business, such collaborations can require

dramatic differences2. For participant A, watching videos. compromises in how research questions are

median use over the 3 weeks was 3.67 hours defined and which data are made available,

per day. For participant B, it was 4.68 hours, Content. During the 3 weeks, participant A and involve lengthy and legally cumbersome

an hour (27.5%) more. engaged with 26 distinct applications. More administration. And ultimately, there is

than half of these (53.2%) were social-media nothing to compel companies to share data

Pattern. The distribution of time spent apps (mostly Snapchat and Instagram). relevant to academic research.

using phones during the day differed even Participant B engaged with 30 distinct To explore more freely, academics need to

more. On average, participant A’s time was applications, mostly YouTube (50.9% of the collect the data themselves. The same is true if

spread over 186 sessions each day (with a total). they are to tackle questions that need answers

session defined as the interval between the Zooming deeper into specific screen within days — say, to better understand the

screen lighting up and going dark again). content reveals even more. For participant B, effects of a terrorist attack, political scandal

For A, sessions lasted 1.19 minutes on on average, 37% of the screenshots for or financial catastrophe.

average. By contrast, participant B’s time was a single day included food — pictures of Thankfully, Screenomics and similar plat-

spread over 26 daily sessions that lasted, food from various websites, photos of B’s forms are making this possible.

on average, 2.54 minutes. So one of the own food, videos of other people eating or In our experience, people are willing to

adolescents turned their phone on and off cooking, and food shown in a game involving share their data with academics. The harder

seven times more than the other, using it in the running of a virtual restaurant. problem is that collecting screenomics data

bursts that were about one-third the length In a survey, both adolescents might have rightly raises concerns about privacy and sur-

of the other’s sessions. reported that they used ‘a lot’ of apps, and veillance. Through measures such as encryp-

These patterns could signal important might have given the names of some of tion, secure storage and de-identification, it

psychological differences. Participant A’s them. But the content of their media diets is possible to collect screenomes with due

days were more fragmented, maybe would be impossible to capture. B.R. et al. attention to personal privacy. (All our project

proposals are vetted by university institutional

review boards, charged with protecting human

instance, that levels of well-being are related available from the software and sensors built participants.) Certainly, social scientists can

to how fragmented people’s use of media is, into digital devices (for instance, on time of learn a lot from best practice in the protection

or the content that they engage with. Differ- day, location, even keystroke velocity). and sharing of electronic medical records13

ences in brain structure might be related to In any one screenome, screenshots are the and genomic data.

how quickly people move through cycles of fundamental unit of media use. But the par- Screenomics data should be sifted using a

production and consumption of content. ticular pieces or features of the screenome gamut of approaches — from deep-dive qual-

Differences in performance in cognitive tasks that will be most valuable will depend on the itative analyses to algorithms that mine and

might be related to how much of a person’s question posed — as is true for other ‘omes’. classify patterns and structures. Given how

multitasking involves switching between con- If the concern is possible addiction to mobile quickly people’s screens change, studies

tent (say, from politics to health) and applica- devices, then arousal responses (detected by should focus on the variation in an individ-

tions (social media to games), and how long a change in heart rate, say) associated with ual’s use of media over time as much as on

they spend on each task before switching. the first screen experienced during a session differences between individuals and groups.

might be important to measure. If the concern Ultimately, researchers will be able to inves-

The Human Screenome Project is the extent to which social relationships tigate moment-by-moment influences on

So, how can we do better? What’s needed dictate how political news is evaluated, then physiological and psychological states, the

is a collective effort to record and analyse the screenshots that exist between ‘social’ sociological dynamics of interpersonal and

everything people see and do on their screens, and ‘political’ fragments in the screenome group relations over days and weeks, and even

the order in which that seeing and doing sequence might be the crucial data to analyse. cultural and historical changes that accrue

occurs, and the associated metadata that are (News items flagged by a close friend might be over months and years.

316 | Nature | Vol 577 | 16 January 2020

©

2

0

2

0

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

ALL IN THE DETAILS Some might argue that screenomics data

Recordings of screenshots every five seconds reveal substantial differences in how are so fine-grained that they invite researchers

two adolescents use their smartphones over 21 days (see ‘Under the microscope’).

to focus on the minutiae rather than the big

Comics Video players and editors Communications picture. We would counter that today’s digi-

Photography Social Games Education Study Tools Music and audio tal technology is all about diffused shards of

Creating content (not shown on the larger figure) experience. Also, through the approach we

Participant A

propose, it is possible to zoom in and out,

Participant A’s time was spread over 186 sessions per day (with a session defined as the interval to investigate how the smallest pieces of the

between the screen lighting up and going dark again). Each session lasted 1.19 minutes on average. screenome relate to the whole. Others might

1 argue that even with this better microscope,

2 we will not find anything significant. But if

3 relationships between the use of media and

4 people’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours

5

continue to be weak or non-existent, at least we

6

7 could have greater confidence as to whether

8 current concerns are overblown.

9 The approach we propose is complex, but no

10 more so than the assessment of genetic predic-

11

Day

tors of mental and physical states and behav-

12

13 iours. Many years and billions of US dollars

14 have been invested in other ‘omics’ projects. In

15 genomics, as in neuroscience, planetary science

16 and particle physics, governments and private

17

18

funders have stepped up to help researchers

19 gather the right data, and to ensure that those

20 data are accessible to investigators globally.

21 Now that so much of our lives play out on our

06:00 08:00 10:00 12:00 14:00 16:00 18:00 20:00 22:00 00:00 screens, that strategy could prove just as valu-

Time able for the study of media.

The authors

Zooming in on 2 hours of participant A’s activity on Byron Reeves is a professor of communication

day 16 reveals more about how they spent their time.

at Stanford University, California, USA.

More than half of the apps that A engaged with were

types of social media (mostly Snapchat and Instagram). Thomas Robinson is a professor of child

health, paediatrics and medicine, and director

Participant B

Participant B’s time was spread over 26 sessions per day, lasting 2.54 minutes on average.

of the Stanford Solutions Science Lab at

Stanford University, California, USA. Nilam

1 Ram is a professor of human development

2

and psychology, and director of the

3

4

Quantitative Developmental Systems Group at

5 Pennsylvania State University, University Park,

6 Pennsylvania, USA.

7 e-mails: reeves@stanford.edu; tom.robinson@

8

stanford.edu; nur5@psu.edu

9

10

11

Day

1. Yeykelis, L., Cummings, J. J. & Reeves, B. J. Commun. 64,

12

167–192 (2014).

13

2. Ram, N. et al. J. Adolesc. Res. 35, 16–50 (2020).

14 3. Hancock, J., Liu, X., French, M., Luo, M. & Mieczkowski,

15 H. Social media use and psychological well-being: a

16 meta-analysis. Paper presented at 69th Annu. Conf. Int.

17 Commun. Assoc., Washington DC (2019).

18 4. Prior, M. Polit. Commun. 30, 620–634 (2013).

19 5. Niederdeppe, J. Commun. Meth. Measures 10, 170–172

20 (2016).

6. Araujo, T., Wonneberger, A., Neijens, P. & de Vreese, C.

21

Commun. Meth. Measures 11, 173–190 (2017).

06:00 08:00 10:00 12:00 14:00 16:00 18:00 20:00 22:00 00:00 7. Naab, T. K., Karnowski, V. & Schlütz, D. Commun. Meth.

Measures 13, 126–147 (2019).

Time

8. Junco, R. Comp. Human Behav. 29, 626–631 (2013).

9. Paulus, M. P. et al. Neuroimage 185, 140–153 (2019).

10. Yeykelis, L., Cummings, J. J. & Reeves, B. Media Psychol.

21, 377–402 (2018).

11. Reeves, B. et al. Human–Comp. Interact. 34, 1–52 (2019).

12. King, G., & Persily, N. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. https://doi.

Participant B engaged with 30 distinct org/10.1017/S1049096519001021 (2019).

applications, mostly YouTube. 13. Parasidis, E., Pike, E. & McGraw, D. N. Engl. J. Med. 380,

1493–1495 (2019).

Nature | Vol 577 | 16 January 2020 | 317

©

2

0

2

0

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Comment: How Social Media Affects Teen Mental Health: A Missing LinkDocument3 pagesComment: How Social Media Affects Teen Mental Health: A Missing LinkWilliam Hernandez GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- The School ExperimentDocument4 pagesThe School ExperimentscribbogPas encore d'évaluation

- Comment: Map Clusters of Diseases To Tackle MultimorbidityDocument3 pagesComment: Map Clusters of Diseases To Tackle MultimorbidityThiago SartiPas encore d'évaluation

- News in Focus: Giant Health Studies Try To Tap Wearable ElectronicsDocument2 pagesNews in Focus: Giant Health Studies Try To Tap Wearable ElectronicsLuiz Folha FlaskPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023 - Nature - Who Decides The Autism AgendaDocument4 pages2023 - Nature - Who Decides The Autism AgendaEmmerickPas encore d'évaluation

- Weighing The Dangers of CannabisDocument3 pagesWeighing The Dangers of Cannabisfuialapelota15Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Hunt For A Healthy Microbiome: OutlookDocument3 pagesThe Hunt For A Healthy Microbiome: OutlookLindo PulgosoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Epic Battle Against Coronavirus Misinformation and Conspiracy TheoriesDocument4 pagesThe Epic Battle Against Coronavirus Misinformation and Conspiracy TheoriesStefano VecchiPas encore d'évaluation

- AI For ProteinsDocument3 pagesAI For Proteinsssharma7376Pas encore d'évaluation

- Could Obesity PDFDocument2 pagesCould Obesity PDFLivia Maria ConsoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Nature Is Updating Its Advice To Authors On Reporting Race or EthnicityDocument1 pageWhy Nature Is Updating Its Advice To Authors On Reporting Race or Ethnicitychato law officePas encore d'évaluation

- WR5 Weaver 2014 Social Science and Global ChangeDocument4 pagesWR5 Weaver 2014 Social Science and Global ChangemkberloniPas encore d'évaluation

- Comment: Two Years of COVID-19 in Africa: Lessons For The WorldDocument4 pagesComment: Two Years of COVID-19 in Africa: Lessons For The Worldotis2ke9588Pas encore d'évaluation

- Antibiotics - Small Molecule - Not - B - Developed d41586-020-02884-3Document3 pagesAntibiotics - Small Molecule - Not - B - Developed d41586-020-02884-3SHINDY ARIESTA DEWIADJIEPas encore d'évaluation

- Careers: Paths Less TravelledDocument4 pagesCareers: Paths Less TravelledJuan David Rodriguez HurtadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Did The Worlds Pandemic Warning System Fail When COVID 19 HitDocument2 pagesWhy Did The Worlds Pandemic Warning System Fail When COVID 19 HitGail HoadPas encore d'évaluation

- Design AI So That It's FairDocument3 pagesDesign AI So That It's FairmjohannakPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Report of SipDocument27 pagesFinal Report of SipSrikant PurwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Nat Hum Beh 2017 Factors Driving Attention in Visual SearchDocument8 pagesNat Hum Beh 2017 Factors Driving Attention in Visual Searchlemmy222Pas encore d'évaluation

- Covid and KidsDocument3 pagesCovid and Kidsumberto de vonderweidPas encore d'évaluation

- New Pedagogical Possi Bilities in post-COVID Higher Ed Ucation and Impact On Student EngagementDocument24 pagesNew Pedagogical Possi Bilities in post-COVID Higher Ed Ucation and Impact On Student EngagementAmit DeyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Process of Care: EditorialDocument1 pageThe Process of Care: EditorialGarry B GunawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Where I Work: Lucía SpangenbergDocument1 pageWhere I Work: Lucía SpangenbergAnahí TessaPas encore d'évaluation

- Big Brain, Big DataDocument3 pagesBig Brain, Big DataDejan Chandra GopePas encore d'évaluation

- News in Focus: Omicron Likely To Weaken Covid Vaccine ProtectionDocument2 pagesNews in Focus: Omicron Likely To Weaken Covid Vaccine ProtectionSobek1789Pas encore d'évaluation

- Are Repeat COVID Infections DangerousDocument3 pagesAre Repeat COVID Infections DangerousJuan MPas encore d'évaluation

- National, Regional, and Global GovernanceDocument25 pagesNational, Regional, and Global GovernanceAbhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Survival of The LittlestDocument4 pagesSurvival of The LittlestJavier BlancoPas encore d'évaluation

- Unpaywall ArticleDocument2 pagesUnpaywall ArticleChristian HdezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Rise of Psychedelic PsychiatryDocument4 pagesThe Rise of Psychedelic PsychiatryAndreia SiqueiraPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Climate Change Through A Poverty LensDocument7 pages2 Climate Change Through A Poverty LensAngku AnazmyPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 1038@sj BDJ 2016 855Document8 pages10 1038@sj BDJ 2016 855Sofia PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Could An Infection Trigger Alzheimer's Disease?Document5 pagesCould An Infection Trigger Alzheimer's Disease?BereRodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Lawwithoutwalls: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument8 pagesLawwithoutwalls: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchAleck BelcherPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Social MediaDocument15 pagesImpact of Social MediaVaishnavi khotPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Genetics of IntelligenceDocument12 pagesThe New Genetics of IntelligenceKasperiSoininenPas encore d'évaluation

- Distribution of PowerDocument65 pagesDistribution of PowerJose Luis Gonzalez GalarzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature Comment - Triangulation Instead of ReplicationDocument3 pagesNature Comment - Triangulation Instead of ReplicationfacefacePas encore d'évaluation

- List of IllustrationsDocument17 pagesList of IllustrationsTanveer KaziPas encore d'évaluation

- WffleDocument3 pagesWffledeshanPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 1038@nrurol 2018 1Document15 pages10 1038@nrurol 2018 1cristianPas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering The Microbiome: OutlookDocument3 pagesEngineering The Microbiome: OutlookLindo PulgosoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ten Twitter TrendsDocument1 pageTen Twitter Trendsapi-13128630100% (2)

- Ómicron and Long-Term ImmunityDocument4 pagesÓmicron and Long-Term ImmunityImpresiones NaranjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation 1Document23 pagesPresentation 1hauwabintumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Kiara Wright 15Document15 pagesKiara Wright 15AmandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Digital Marketing, Analytics and Storytelling With Data Individual Portfolio - Storytelling With DataDocument13 pagesDigital Marketing, Analytics and Storytelling With Data Individual Portfolio - Storytelling With DatarajeshPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On The Household Passive Leisure Consumption Pattern of Breadwinners Within Metro Manila Under The Burden of Value-Added TaxDocument25 pagesA Study On The Household Passive Leisure Consumption Pattern of Breadwinners Within Metro Manila Under The Burden of Value-Added TaxNixPas encore d'évaluation

- A Biologist Talks To A PhysicistDocument4 pagesA Biologist Talks To A PhysicistBzar Blue ClnPas encore d'évaluation

- Sohn 2016Document3 pagesSohn 2016Maxtron MoonPas encore d'évaluation

- Report SuitDocument32 pagesReport SuitVincenzo MorelliPas encore d'évaluation

- News in Focus: Alzheimer'S Drug Slows Mental Decline in Trial - But Is It A Breakthrough?Document2 pagesNews in Focus: Alzheimer'S Drug Slows Mental Decline in Trial - But Is It A Breakthrough?Al CavalcantePas encore d'évaluation

- Are You Familiar With Desktop Computers, Laptops and Tablets?Document12 pagesAre You Familiar With Desktop Computers, Laptops and Tablets?Daniel MutascuPas encore d'évaluation

- Cover JocisDocument2 pagesCover JocisMaria Leonor FigueiredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nation BrandingDocument36 pagesNation BrandingHarun or RashidPas encore d'évaluation

- Lectura CifuentesDocument25 pagesLectura CifuentesJohanss PCPas encore d'évaluation

- The Use of Digital Social Networks From An Analytical Sociology Perspective: The Case of SpainDocument21 pagesThe Use of Digital Social Networks From An Analytical Sociology Perspective: The Case of SpainFilioscribdPas encore d'évaluation

- Webley Social Studies SbaDocument29 pagesWebley Social Studies Sbakimona webleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Fed Up and Burnt Out: Quiet Quitting' Hits Academia: Advice, Technology and ToolsDocument3 pagesFed Up and Burnt Out: Quiet Quitting' Hits Academia: Advice, Technology and ToolsMustafa ŞEKERPas encore d'évaluation

- SuperVision: An Introduction to the Surveillance SocietyD'EverandSuperVision: An Introduction to the Surveillance SocietyPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020 State of The Community: Transitional Aged YouthDocument82 pages2020 State of The Community: Transitional Aged YouthRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Health Workforce ReportDocument7 pagesMental Health Workforce ReportRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 California Childrens Report Card CompressedDocument104 pages2022 California Childrens Report Card CompressedRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 California Childrens Report Card CompressedDocument104 pages2022 California Childrens Report Card CompressedRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Reeves Et Al. (2022)Document22 pagesReeves Et Al. (2022)Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Health Workforce ReportDocument7 pagesMental Health Workforce ReportRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Pronoun Guide For Instructors - 10.2019Document2 pagesPronoun Guide For Instructors - 10.2019Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Strain of Caregiving ReportDocument25 pagesThe Strain of Caregiving ReportRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Healthcare & IncomeDocument9 pagesHealthcare & IncomeRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Black Teens:SuicideDocument41 pagesBlack Teens:SuicideRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Policy Platform Up To 12-09-16Document76 pagesPublic Policy Platform Up To 12-09-16Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Relationships First:SEARCH INST.Document20 pagesRelationships First:SEARCH INST.Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Health Services Stakeholders and Family EngagementDocument30 pagesMental Health Services Stakeholders and Family EngagementRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- DDK The Geography of Child Opportunity 2020Document54 pagesDDK The Geography of Child Opportunity 2020Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- National Suicide Prevention StrategyDocument184 pagesNational Suicide Prevention StrategyRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- 2019 NAMI California Legislative Wrap Up: Priority Legislation That Did Not Move Forward This YearDocument6 pages2019 NAMI California Legislative Wrap Up: Priority Legislation That Did Not Move Forward This YearRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of CA' Dept of Behavioral Health PDFDocument466 pagesReview of CA' Dept of Behavioral Health PDFRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender & Mental HealthDocument25 pagesGender & Mental HealthMarcPas encore d'évaluation

- Ram Etal Screenomics JAR 2020Document35 pagesRam Etal Screenomics JAR 2020Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Ram Etal Screenomics JAR 2020Document35 pagesRam Etal Screenomics JAR 2020Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- US FINAL 13 Reasons Why Discussion GuideDocument10 pagesUS FINAL 13 Reasons Why Discussion GuideRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- ISMICC (Fed. RPT On Serious MI)Document120 pagesISMICC (Fed. RPT On Serious MI)Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Parity at RiskDocument23 pagesParity at RiskRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Ram Etal Screenomics JAR 2020Document35 pagesRam Etal Screenomics JAR 2020Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Meeting Draft of Final Report - November 1, 2017Document131 pagesMeeting Draft of Final Report - November 1, 2017Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- A Handbook For Advocates: "If Not Us, Who? If Not Now, When?"Document22 pagesA Handbook For Advocates: "If Not Us, Who? If Not Now, When?"Roxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016NAMI AnnualReportDocument16 pages2016NAMI AnnualReportRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- HighSchoolSurveyResults ExecSumDocument20 pagesHighSchoolSurveyResults ExecSumRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Mind Institute 2016 Childrens Mental Health ReportDocument15 pagesChild Mind Institute 2016 Childrens Mental Health ReportRoxanne ReevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Heart of ThelemaDocument15 pagesHeart of ThelemaSihaya Núna100% (1)

- Service BlueprintDocument10 pagesService BlueprintSam AlexanderPas encore d'évaluation

- Aristotle Nicomachean EthicsDocument10 pagesAristotle Nicomachean EthicsCarolineKolopskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Animal RightsDocument5 pagesAnimal RightsAfif AzharPas encore d'évaluation

- Money As Tool Money As Drug Lea WebleyDocument32 pagesMoney As Tool Money As Drug Lea WebleyMaria BraitiPas encore d'évaluation

- Secret Teachings of All Ages - Manly P HallDocument3 pagesSecret Teachings of All Ages - Manly P HallkathyvPas encore d'évaluation

- Math LogicDocument44 pagesMath LogicJester Guballa de Leon100% (1)

- LR Situation Form (1) 11Document13 pagesLR Situation Form (1) 11Honey Cannie Rose EbalPas encore d'évaluation

- Warnier Jean-Pierr Marching The Devotional Bodily Material K ReligionDocument16 pagesWarnier Jean-Pierr Marching The Devotional Bodily Material K Religioncristian rPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1-Law and Legal ReasoningDocument9 pagesChapter 1-Law and Legal Reasoningdimitra triantosPas encore d'évaluation

- الترجمة اليوم PDFDocument155 pagesالترجمة اليوم PDFMohammad A YousefPas encore d'évaluation

- A Human Rights Approach To Prison Management: Handbook For Prison StaffDocument169 pagesA Human Rights Approach To Prison Management: Handbook For Prison StaffAldo PutraPas encore d'évaluation

- Physics Assessment 3 Year 11 - Vehicle Safety BeltsDocument5 pagesPhysics Assessment 3 Year 11 - Vehicle Safety Beltsparacin8131Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy and Sociology of ScienceDocument6 pagesPhilosophy and Sociology of SciencereginPas encore d'évaluation

- Tiainen Sonic Technoecology in The Algae OperaDocument19 pagesTiainen Sonic Technoecology in The Algae OperaMikhail BakuninPas encore d'évaluation

- Makalah Narative Seri 2Document9 pagesMakalah Narative Seri 2Kadir JavaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guidelines Public SpeakingDocument4 pagesGuidelines Public SpeakingRaja Letchemy Bisbanathan MalarPas encore d'évaluation

- Enhancing The Value of Urban Archaeological SiteDocument53 pagesEnhancing The Value of Urban Archaeological SitePaul VădineanuPas encore d'évaluation

- An Interview With Thomas Metzinger What Is The SelfDocument2 pagesAn Interview With Thomas Metzinger What Is The SelfIdelfonso Vidal100% (1)

- Chinese Language Textbook Recommended AdultDocument10 pagesChinese Language Textbook Recommended Adulternids001Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Autopoiesis of Social Systems-Kenneth D. BaileyDocument19 pagesThe Autopoiesis of Social Systems-Kenneth D. BaileycjmauraPas encore d'évaluation

- Unesco - SASDocument4 pagesUnesco - SASmureste4878Pas encore d'évaluation

- Garry L. Hagberg-Fictional Characters, Real Problems - The Search For Ethical Content in Literature-Oxford University Press (2016) PDFDocument402 pagesGarry L. Hagberg-Fictional Characters, Real Problems - The Search For Ethical Content in Literature-Oxford University Press (2016) PDFMaja Bulatovic100% (2)

- Faulkner Sound and FuryDocument3 pagesFaulkner Sound and FuryRahul Kumar100% (1)

- A00 Book EFSchubert Physical Foundations of Solid State DevicesDocument273 pagesA00 Book EFSchubert Physical Foundations of Solid State DevicesAhmet Emin Akosman100% (1)

- Geography World Landmark Game Presentation-3Document12 pagesGeography World Landmark Game Presentation-34w6hsqd4fkPas encore d'évaluation

- Jean Molino: Semiologic TripartitionDocument6 pagesJean Molino: Semiologic TripartitionRomina S. RomayPas encore d'évaluation

- Report On Attendance: No. of School Days No. of Days Present No. of Days AbsentDocument2 pagesReport On Attendance: No. of School Days No. of Days Present No. of Days AbsentJenelin Enero100% (4)

- The Anthropocene Review 1 2Document95 pagesThe Anthropocene Review 1 2bordigaPas encore d'évaluation

- Decalogues and Principles PDFDocument31 pagesDecalogues and Principles PDFهؤلاء الذين يبحثونPas encore d'évaluation