Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Origins

Transféré par

Nainesh Mutha0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

9 vues7 pagesLogistics originated in the military's need to supply themselves with arms, ammunition and rations as they moved from their base to a forward position. Logistics evolved during planning and exercising crusades and military expeditions, as well as with the development of trade. The beginning of logistics theory can be dated to second world war, and in business logistics, to 1950's.

Description originale:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentLogistics originated in the military's need to supply themselves with arms, ammunition and rations as they moved from their base to a forward position. Logistics evolved during planning and exercising crusades and military expeditions, as well as with the development of trade. The beginning of logistics theory can be dated to second world war, and in business logistics, to 1950's.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

9 vues7 pagesOrigins

Transféré par

Nainesh MuthaLogistics originated in the military's need to supply themselves with arms, ammunition and rations as they moved from their base to a forward position. Logistics evolved during planning and exercising crusades and military expeditions, as well as with the development of trade. The beginning of logistics theory can be dated to second world war, and in business logistics, to 1950's.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 7

Origins

The term "logistics" originates from the ancient Greek "λόγος"

("logos"—"ratio, word, calculation, reason, speech, oration").

Logistics is considered to have originated in the military's need to supply themselves with

arms, ammunition and rations as they moved from their base to a forward position.

Before the 1950s, logistics was thought of in military terms. It had to do

with procurement, maintenance, and transportation of military facilities,

materiel, and personnel

Logistic is the art and science of management, engineering and technical

activities concerned with requirements, design and supplying and

maintaining resources to support objectives, plans and operations ''

Logistics evolved during planning and exercising crusades and

military expeditions, as well as with the development of trade. The

practicality of logistics is also seen with its involvement in everyday life.

The beginning of logistics theory can be dated to second world war, and in

business logistics, to 1950’s. During the Second World War, also the

computer age was started, which enabled analysis with the evolving

operations research models. The main application areas of operations

research in the beginning involved logistics problems such as transportation

routes, inventory models.

Logistics management as an independent discipline started to evolve

under management science. Models geared to minimization of costs were

developed. Both modelling and OR methods developed. Since these models

often were simplifications, the solutions lacked true applicability.

In business world, external situations such as oil crisis, growing

competition, and increasing customer demands made logistics a

management issue, and in gaining more importance, logistics became

eventually the top level issue in management. Integration of production

scheduling and materials management was needed, and on the other hand,

transports were analysed taking inventories into consideration at the same

time.

Network models for restructuring the distribution networks were taken

into use. Several rounds of streamlining the number of warehouses in

distribution networks have been seen. The models initially were facilities

location problems, now the analysis is based on costs, availability, and

delivery service levels in an environment of many factories, markets,

products, and time periods.

OR-models started to become too complex, and the same problems

with simplifications remained. Logistics became a management discipline in

its own right.

Control over own management environment had to widened,

especially when materials management was considered. Logistical efficiency

became a competitive factor when providing customer service, and obtaining

cost efficiency. During structural change, outsourcing of non-core functions

became a trend. Most companies outsourced first their transports, then also

their inventories and sourcing, so most of the logistical operations were

outsourced. Partnerships, alliances, and cooperation became a management

strategy as well as a research area.

Forecasts of demand have become extremely crucial. Seasonality,

perishability, risk handling, shorter life cycles, shorter times to market all

make more demands on both the accuracy and quickness of forecasts. For all

participants in the logistics chain, they have great importance. Visibility will

be the main strategic competitive issue in logistics management across

company borders.

2. Brief history

Early references to logistics can be located in business literature. Prior

to the 1950’s, the typical enterprise performed the work of logistics purely

on functional basis. Bowersox and Closs [4] comment that the continuous

pressure for profit improvement since then along with erratic market

conditions puts the focus on cost containments, avoidance, and reduction.

According to Ballou [2], logistics management, as a discipline in

management science and practice, was defined in US in 1950-60’s when the

potential of efficient material distribution to decrease companies’ direct

product costs was realized. The physical distribution models were developed

because of the following four factors: 1) shifts in consumer demand patterns

and attitudes toward more demanding needs for high availability and variety

of products, 2) cost pressures on industry, 3) progress in computer

technology, and 4) the influences of military experience.

The change in logistics practices faced significant opposition.

Managers, responsible for specific functions, were not happy with

organizational changes that were considered necessary for implementing

logistics in broader meaning. Bowersox and Closs [4] comment further that

return on investment became harder to distinguish in integrated logistics.

During the oil crisis in 1970’s , both transportation costs and interest

rates (thus also inventory carrying costs) increased simultaneously, and the

importance of logistics was really understood by top management.

Optimization of physical distribution alone was not enough, it was necessary

to integrate purchasing and materials handling into it as well.

The most significant drivers for integrated logistics during 1980’s and

early 1990’s were listed by Bowersox and Closs [4] as 1) significant

regulatory change, 2) microprocessor commercialisation, 3) information

revolution, 4) widespread adoption of quality improvements, and 5) the

growth of partnerships and strategic alliances.

This integration process was leading to an evolution of logistics

management that according to the increasing number of logistics literature,

e.g. Langley and Holcomb [18], Gattorna and Walters [11], and Gopal and

Cypress [12] in addition to earlier edition from year 1992 of Ballou [2] can

be considered to be the combination physical distribution and materials

management.

Gradually logistics management became cross functional within the whole

organization (Christopher [8]).

Porter [23] published in 1985 the famous doctrine of value chain and value

system. Each activity in a company should be adding value to the value

chain of the customer. In the value concept, logistics plays very central role

in creating value for the customer, as both inbound and outbound logistics

are presented as primary activities in the chain. Logistics increased

importance, as it was seen as an activity that enables companies to improve

customer value, and not only regarded internally as cost-efficiency target.

This lead further to value stream mapping presented by Hines et al. [14]

An abundance of definitions of logistics have been presented. The term

Supply Chain was introduced, and had to be distinguished from logistics.

There is a view that logistics is contained in a company’s internal processes,

whereas supply chain is a more holistic concept (Christopher [8]). The

current interpretation is also that the supply chain creates products and

services that are transferred from suppliers to end customers. This

interpretation has been complemented with the term demand chain, defined

to transfer demand information from end customer markets to suppliers.

Combined, demand and supply chain create demand-supply chain, an end-

to-end network (Harrison and van Hoek [13]). It can be noted, that the

traditional term logistics chain has also been defined to cover the material

flow from raw material end to final customer end, the demand information

flow to the opposite direction, and transfer of payments as well; the modern

view is that in the supply chain, logistics is a subset (Harrison and van Hoek

[13]).

Analytical approaches even in the beginning of 2000’s rely on traditional

methods of statistics and operations research, as is displayed by Chopra and

Meindl [6], and Shapiro [24].

3. Evolution platforms

The evolution of production supply chains depends on the previous

platforms of best practice. Hughes et al. [15] describe this by the stages seen

in the supply chains over the past forty years. In the 1960’s, the goal was to

secure the stability of production, which was achieved by modelling and

optimising the economic batch sizes, safety stocks, and reorder levels. This

provided a natural platform for adoption of material requirements planning

(MRP) in the 1970’s and early 1980’s. MRP is built on a push system, where

materials are ordered against a projected demand. Manufacturing is arranged

along ordered schedules. MRP attempts to eliminate safety stock and cycle

stock, Flexibility is taken up by varying the demand on the suppliers.

Simultaneously, in Japan, just-in-time (JIT) practices were evolving

alongside with total quality management (TQM), with the goal to eliminate

all waste from manufacturing and inventories. JIT and TQM were business

philosophies supported by several interconnected principles, which were

defined around the three QCD principles: a continually improving quality

assurance system to meet customer requirements, a continually improving

cost management system to provide the product at an attractive price to the

customer while securing reasonable profits for the company, and a

continually improving delivery system to ensure that products arrive on

time. Huge improvements were seen. Without integrating all three

principles, there would have been the risk of concentrating on trading costs

for quality and customer response. JIT production is a pull system. Capacity

is matched to the demand. Production patterns are regular, but

manufacturing systems are flexible. Batch quantities are economic, supplier

lead times are short, product range was narrow, and demand patterns in the

market are regular. JIT prevailed in the 1980’s and in the beginning of

1990’s.

JIT was a natural platform for the lean production and lean supply systems

emerging in the 1990’s. In lean systems, all waste, also time wastes, were

eliminated. Total inventories, for production, in production work in process,

and in finished goods inventories, were minimized. Cost transparency in the

supply chain was necessary, for production flexibility, multi-skilled workers

were needed, work queues were shortened, change-over times were reduced,

product variability was great but product volumes were low. During this

period, synchronous manufacturing was introduced, product modularisation,

postponements and pushing order penetration point upstream (Krajewski and

Ritzman [17]). At every stage, continuous improvement was the target.

Value stream management and value stream mapping was one of the

methods to achieve lean management and excellence in the supply chains

(Hines et al. [14]).

The need for greater flexibility and shorter times to market and customers,

brought out the next stage of responsive supply chains. Quick response to

customer requirements, supply flexibility, and customized manufacturing are

all geared for better customer service. Production schedules were

synchronized with final demand, supply processes were controlled, and

capability to integrate trading partners, full use of electronic commerce, and

concurrent product development were taken into use.

Simchy-Levy et al. [25] note that, in 2000’s, e-business has already

brought out a significant change. Improvement in the service level and

inventory level could not be achieved simultaneously earlier. Recent

developments in information technology and communication technology,

together with better understanding of supply chain strategies, have led to

innovative approaches so that the firm can improve both objectives

simultaneously.

From lean manufacturing and supply chains, the next platform to emerge

at the end of 1990’s, is the process model and the agile supply chain

(Harrison and van Hoek [13]). These involve goods and products with short

life cycles, volatile demand, high product variety, customer service driver is

availability, not cost alone. Profit margin is high, and dominant cost factor is

marketability cost. Stockout penalties are immediate and volatile,

information enrichment is obligatory, and forecasting methods have become

consultative. The need for new customer relation management systems, with

better forecasting capabilities is imminent. Agility means, that capacity and

demand variances have to be benefited.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- MusicDocument2 pagesMusicNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

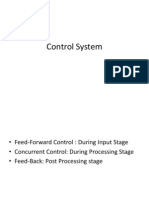

- Control SystemDocument2 pagesControl SystemNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- MarketingDocument2 pagesMarketingNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- GreatDocument2 pagesGreatNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Essence of SuccessDocument10 pagesEssence of SuccessNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Become A ManagerDocument1 pageHow To Become A ManagerNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- International MarketingDocument75 pagesInternational MarketingNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- MIS IntroDocument11 pagesMIS IntroNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- MNEDocument15 pagesMNENainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- International Business ManagementDocument22 pagesInternational Business ManagementNainesh Mutha100% (1)

- Recessionary Cost ManagementDocument2 pagesRecessionary Cost ManagementNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Network IntegrationDocument19 pagesNetwork IntegrationNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Network IntegrationDocument19 pagesNetwork IntegrationNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Procurement and Manufacturing FinalDocument92 pagesProcurement and Manufacturing FinalNainesh MuthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Digital Literacy: A Conceptual Framework For Survival Skills in The Digital EraDocument14 pagesDigital Literacy: A Conceptual Framework For Survival Skills in The Digital EraSilvia CarvalhoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ip Nat Guide CiscoDocument418 pagesIp Nat Guide CiscoAnirudhaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Biterm Topic Model For Short Texts SlideDocument19 pagesA Biterm Topic Model For Short Texts Slideson070719969Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lab ManualDocument9 pagesLab ManualMohit SinhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Customer Interface Publication: KCH CIP015Document8 pagesCustomer Interface Publication: KCH CIP01560360155Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kapil Sharma ResumeDocument4 pagesKapil Sharma ResumeKapil SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- RRB ALP CBT 1 PAPER 31 Aug 2018 Shift 03 PDFDocument28 pagesRRB ALP CBT 1 PAPER 31 Aug 2018 Shift 03 PDFmaheshPas encore d'évaluation

- Siklus RankineDocument26 pagesSiklus RankineArialdi Almonda0% (1)

- Boq IDocument7 pagesBoq IAmolPas encore d'évaluation

- Machxo2™ Family Data Sheet: Ds1035 Version 3.3, March 2017Document116 pagesMachxo2™ Family Data Sheet: Ds1035 Version 3.3, March 2017Haider MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual - Submersible PumpDocument4 pagesManual - Submersible PumpcodersriramPas encore d'évaluation

- Gmail - CAMPUS DRIVE NOTIFICATION - Himadri Speciality Chemical LTDDocument2 pagesGmail - CAMPUS DRIVE NOTIFICATION - Himadri Speciality Chemical LTDShresth SanskarPas encore d'évaluation

- EM Console Slowness and Stuck Thread IssueDocument10 pagesEM Console Slowness and Stuck Thread IssueAbdul JabbarPas encore d'évaluation

- CIV211 - Module1Document49 pagesCIV211 - Module1Dayalan JayarajPas encore d'évaluation

- Expansion Indicator Boiler #1Document6 pagesExpansion Indicator Boiler #1Muhammad AbyPas encore d'évaluation

- Experimental Study On Partial Replacement of Sand With Sugarcane Bagasse Ash in ConcreteDocument3 pagesExperimental Study On Partial Replacement of Sand With Sugarcane Bagasse Ash in ConcreteRadix CitizenPas encore d'évaluation

- FDP ECE BrochureDocument3 pagesFDP ECE BrochureBalasanthosh SountharajanPas encore d'évaluation

- Audit QuickstartDocument6 pagesAudit QuickstarthugorduartejPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hydraulic Pumping SystemDocument12 pagesThe Hydraulic Pumping SystemCarlos Lopez DominguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Math Lesson Plan 7 - Odd & EvenDocument3 pagesMath Lesson Plan 7 - Odd & Evenapi-263907463Pas encore d'évaluation

- Windows 10Document28 pagesWindows 10Vibal PasumbalPas encore d'évaluation

- AE1222-Workbook 2013 - Problems and SolutionsDocument69 pagesAE1222-Workbook 2013 - Problems and SolutionsMukmelPas encore d'évaluation

- Creative Industries Journal: Volume: 1 - Issue: 1Document86 pagesCreative Industries Journal: Volume: 1 - Issue: 1Intellect BooksPas encore d'évaluation

- MHDDocument33 pagesMHDkashyapPas encore d'évaluation

- ECE 551 Assignment 2: Ajit R Kanale, 200132821 January 25, 2017Document5 pagesECE 551 Assignment 2: Ajit R Kanale, 200132821 January 25, 2017Ajit KanalePas encore d'évaluation

- R H R C H E C R: Egenerating The Uman Ight TOA Lean and Ealthy Nvironment in The Ommons EnaissanceDocument229 pagesR H R C H E C R: Egenerating The Uman Ight TOA Lean and Ealthy Nvironment in The Ommons Enaissanceapi-250991215Pas encore d'évaluation

- Compair Fluid Force 4000 IndonesiaDocument3 pagesCompair Fluid Force 4000 Indonesiaindolube75% (4)

- Design of Anchor Bolts Embedded in Concrete MasonryDocument9 pagesDesign of Anchor Bolts Embedded in Concrete MasonryYoesuf DecipherPas encore d'évaluation

- Dahua ITC302-RU1A1Document2 pagesDahua ITC302-RU1A1Dms TsPas encore d'évaluation

- Tower Crane Reference ManualDocument73 pagesTower Crane Reference ManualVazmeque de'Hitcher100% (9)