Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Boys Dont Cry

Transféré par

A_BaeckCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Boys Dont Cry

Transféré par

A_BaeckDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Boys Don't Cry

Review by: Rachel Swan

Film Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Spring 2001), pp. 47-52

Published by: University of California Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2001.54.3.47 .

Accessed: 06/08/2015 06:55

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film

Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 137.248.1.6 on Thu, 6 Aug 2015 06:55:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Boys Don’t Cry

Director: Kimberly Pierce. Producers: Jeffrey Sharp, John

Hart, Eva Kolodner, Christine Vachon. Screenplay: Pierce,

Andy Bienen. Cinematographer: Jim Denault. Fox Searchlight.

I fell in love with Brandon Teena from his érst close-

up in the opening of Kimberly Pierce’s film Boys

Don’t Cry. A blend of Hollywood pinup and storybook

knight-in-shining-arm or, Brandon struck me as the per-

fect mix of boyish geekiness and male chivalry. He’s

a guy who’d slug the big kid who took your lunch

money, but he’d also have been your dream date for

the junior prom. Perhaps it was this awkward boy-next-

door charm that captured the hearts of so many movie-

goers and led to the dazzling success of Boys Don’t

Cry. At the same time, there was something rather jar-

ring in conceiving of Brandon as a new Hollywood

heartthrob. This discomfort was only exacerbated by

the spectacle of sexy starlet Hillary Swank accepting

an Oscar for her role as Brandon. By what weird

alchemy could so many of us fall in love with a boy

who is really a girl?

You don’t have to be a lesbian to identify with

Brandon Teena; in fact, his unflinching, two-fisted

maleness seems to throw a punch at the category of

“butch lesbian” while consolidating a “straight male”

cowboy hero ideal. A convincing boy, Brandon throws

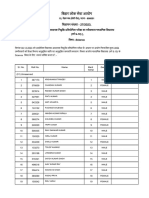

“Boy-next-doo r” charm from Hillar y Swank as

into èux traditional categories of gender, sex, and de-

Brandon Teena.

sire. Moreover, Boys Don’t Cry suggests that gender

is only a dramatic persona. This cannot be dismissed as can of worms opened somewhere in the middle. And

merely esoteric, newfangled, or irrelevant, particularly this élm, with its harrowing docudrama story line, its

if we consider the real rape and murder of Brandon neo-noir intercuts of wasteland Nebraska, and its trans-

Teena as a ritualistic scapegoating of the transgendered gression of gender conventions, seems to go against

Streitpunkt

individual. It is fair to say, then, that the polemics of so- the grain. However, there’s no denying that Boys Don’t

called gender-bending are, or should be, a concern for Cry is a tearjerker; indeed, the pathos of victimization,

mainstream audiences. The killing of Brandon Teena, rape, and cold-blooded murder marks Boys Don’t Cry

which alternately shocks and titillates the viewer with as a melodrama.

its subplot of gender masquerade and violent hate To call this élm melodramatic then is to indicate

crime, stands as an apt allegory for a society coming to that it oscillates between the exhilaration of Brandon’s

terms with “alternative sexualities” and their destruc- gender-bending and the pathos of his victimization.

tion of a sacred order in the universe. In order to recast For the most part, pathos is expressed in the élm’s vi-

Brandon from the role of social misét to that of mar- sual terrain. Falls City, Nebraska, is a Pandora’s box

tyr, he must be presented to us as embodying such a where humans disintegrate from the poison of alcohol

profound moral purity that we are made to feel for him. and incest, where old-guard sexism is a fulcrum for

Boys Don’t Cry, like any melodrama, sublimates human interaction, where the women are èinchers and

its messages into a visual theater of gesture. But the the men are éghters. The élm’s èat, posterboard land-

word melodrama leaves most of us with a bad taste in scape of power lines and two-lane roads is a visual ex-

the mouth. We think of a melodramatic élm in terms of pression of pathos and doom , as are the small

predigested plots and a èat repertoire of characters: a Nebraskan hovels in which most of the action takes

feel-gooder damsel, a do-gooder Prince Charming, a place. In the Freudian sense, this is an environment of

Film Quarterly, Vol. no. 54, Issue no. 3, pages 47-52. ISSN: 0015-1386. © 2001 by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Send requests for

permission to reprint to: Rights and Permissions, University of California Press, Journals Division, 2000 Center Street, Suite 303, Berkeley, CA 94704-1223. 47

This content downloaded from 137.248.1.6 on Thu, 6 Aug 2015 06:55:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

repression and sublimation, and psychic evils strain to aesthetically appealing female form, the ideal object

break through the thin social tissue. In one scene, for a male spectator. The camera cuts to a parallel shot

Lana’s mother, èaunting her thighs in a pink microskirt, of Brandon in men’s briefs, his breasts bound tightly to

dances cheek-to-cheek with the film’s villain, John. his chest with elastic gauze. In this shot Brandon is po-

Later John drugs his four-year-old daughter with booze sitioned in the same way as Lana was, standing before

and tries to molest her. When the kid pees on him, John a full-length mirror with his hands clasped over his èat

lets out a long stream of invectives (“Little bitch!”), belly. Since Brandon in this moment is unadorned in

pegging him as the archetypal redneck chauvinist, his male costume, we are made to see the similarity of

someone who poses a threat not only to the female the two female bodies. Moments later, Brandon puts on

characters of the élm, but to Brandon as well. Charac- a T-shirt and jeans and slips a plastic penis into his

ters alternately narcotize and release themselves in or- pants. He waltzes back to the mirror, pointing two pis-

giastic drug and alcohol binges; Lana’s mom and John tol-like fingers and triumphantly declaring, “I’m an

chug beers at the breakfast table; Lana and Katie lie asshole!” The scene suggests that Brandon obfuscates

on a child’s merry-go-round and sniff from an aerosol his sex in a theatrical guise of maleness, that his cos-

paint can. The other villain, Tom, cuts himself to ex- tume functions to defy, but also to conceal, the banal-

ternalize his pathos. ity of his female body. This observation makes

But Boys Don’t Cry isn’t bleak at every moment. Brandon’s gender masquerade at once subversive and

It is exhilarating to watch Brandon Teena prevail over problematic.

traditional bedrock notions of femininity, to see him Gary Morris claims that Brandon’s female body

present himself not as a tomboy or tranny, but as an counterbalances his male performance with “devastat-

“ideal” heterosexual male. In the élm’s opening we are ing moments when Brandon is forced to acknowledge

introduced to him in an extended close-up shot during Teena—desperately binding her breasts, checking her

which he spits on two éngers and slicks back his hair, underwear, nervously stuffing socks down her pants,

tilts his chin up, straightens his shirt collar, adorns him- practicing boy smiles and boy leers in the mirror.” 2

self with a cigarette and a ten-gallon hat, and grins tri- Nonetheless, we can also argue that Brandon chal-

umphantly at the camera. This excessive sequence of lenges the norms of gender in Boys Don’t Cry by pro-

gestures coheres into an unabashed theater of male- ducing for himself a body that deées the categories of

ness, particularly since Brandon is gazing the whole his sex. Kimberly Pierce describes Brandon as “a

time into a mirror. trailer-park kid who reinvented himself in his bed-

We watch Brandon watch himself; the narcissistic room” 3 and thus bandied with the terms of gender.

gesture seems more female than male, performed by The symmetry of Brandon and Lana in their

one who considers herself to be an object of vision. stripped-down, sexed bodies is renegotiated in the

But to place vanity and femininity cheek-by-jowl is film’s scenes of pathos and action. In the opening

to regress to gender essentialism. Perhaps this long scenes Brandon, performing as a male, drag-races,

close-up functions instead to assert the theatricality of bumper-skis, gets into barroom brawls over girls, and

maleness, the “feminine” self-consciousness of a boy escapes cops and vigilante dyke-bashers in the nick of

inspecting himself in the mirror, trying to get the right time. This reconéguration of Brandon under the rubric

“look.” To this end, Margo Jefferson declares, “it of “male” action brashly shows up Lana’s pathetic

wouldn’t be so astonishing if she (Brandon) didn’t also “feminine” performance. As Brandon brawls with surly

remind us that every boy has to practice being a boy. rednecks, Lana watches from the sidelines. Her femi-

Getting the walk, the shoulde rs. . . . And finally ninity is conveyed through a vocabulary of gesture

the thrill of getting it right, having that power.” 1 Jeffer- which contrasts with Brandon’s male swaggering: she

son configures Brandon’s performance as a way to stoops over and combs a hand through her hair, con-

seize power rather than as a sign of feeble self- forming to the clichés of the fetishized female.

objectiécation. She complains of the disconsolate life in Falls City,

This is not to refuse the mirror as a critical signi- where she feels hopelessly trapped, she sings a pitiful

éer in Boys Don’t Cry, particularly in its parallel posi- country-western song, “Bluest Stars in Texas,” which

tioning of Brandon and his girlfriend Lana. In one shot, displaces the midwestern bumpkin’s existential angst

for instance, Lana stands before a full-length mirror onto the gloom of trailer parks and lonely hotels. Lana

and scrutinizes her female body. She slumps her shoul- relies on Brandon to save her from the ennui of the

ders and clasps both hands over her belly, sucking it in American heartland, to sweep her into a Chevy pickup

self-consciously, as though to express the desire for an and ride off into the sunset. Brandon promises to de-

48

This content downloaded from 137.248.1.6 on Thu, 6 Aug 2015 06:55:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

one another, categorized respectively

as “male” and “female.”

Brandon also positions himself as

a spectator of Lana by taking pictures

of her with a Polaroid camera. In one

scene she darts coyly from the cam-

era’s gaze, hiding behind trees, placing

her arms over her face, or shielding

her body with her lank hair. These ges-

tures remind us of a woman’s dis-

cométure as an object of a man’s gaze.

Moreover, the camera becomes an in-

strument of Brandon’s pursuance of

Lana; it threatens to capture her fe-

male body for his male viewing plea-

sure. In another scene, Brandon takes

a picture of Lana which she cannot an-

Males gazing . . .

ticipate: she stands at the window of

the factory where she works, casually

liver the nick-of-time rescue expected of the traditional dangling a cigarette, while he posi-

Hollywood hero. tions himself far below with the camera. We see Lana’s

This device of contrasting Brandon’s “masculin- female body as an object, framed both by the window

ity” with Lana’s “femininity” is less obvious in the and the Polaroid camera. When Brandon calls out to

scenes not involving blood-and-thu nder action or tear- Lana she coquettishly brushes her hair from her face as

jerking pathos; instead, this dialectic is played out by though to pose for the male viewer.

positioning Brandon as a spectator of Lana. These For a good two-thirds of the élm, Brandon bravely

scenes are eerie parodies of traditional male and fe- challenges the conventions of sex and gender. His per-

male representations: Lana becomes the object in Bran- formance is galvanizing; we get butterèies watching

don’s presumably male éeld of vision. Of particular him slyly hit on girls at the skating rink, chug beers

importance are two signiéers of fetishization: the stage and fraternize with other “boys,” do pushups in his jail

and the camera. cell. At the same time, you always have an eerie feel-

Brandon first gazes upon Lana as she sings ing that this show won’t hold out; even a spectator who

karaoke on a barroom stage with her friends Candace doesn’t know the real Brandon Teena story will sense

and Kate; Brandon watches with John and Tom. that Brandon is dodging éreballs and will laugh until

Again, gesture becomes an important vehicle of com- one hits him.

munication in this scene. As she sings, Lana slumps, And then Brandon’s masquerade begins to wear

self-consciously aware of the male gaze upon her. thin; stealthy bedroom searches and hearsay disclose

Brandon, Tom, and John sit with their legs spread and his “true” identity to the snoops of Falls City, Nebraska.

their heads cocked unabashedly, each pinching a cig- Things fall apart as the characters of Boys Don’t Cry

arette between his thumb and index égure. The three uncover bits of proof against the “fraudulent” Bran-

male characters’ gestural sym metry sugge sts that don Teena, from a bad check, to a pamphlet on sexual

watching women is for them a fraternal activity, a way identity crisis, to a newspaper clipping which docu-

in which to assert their shared masculinity. This fra- ments the arrest of “Teena Brandon.” Each discovery

ternal ceremony is resonant with real life; the real John is a stab of fear. The tension of Boys Don’t Cry rises to

Lotter said of Brandon in Susan Muska and Greta a brute hysteria which climaxes in the rape of Bran-

Olafsdottir ’s 1998 documentary, The Brandon Teena don Teena. This assault on his usurped “male” body

Story, “We went out drinking together, we’d talk about aims to punish Brandon for transgressing the long-

women, we’d drive around and say ‘Ooh, what about cherished conception of gender as a reèection of sex,

that one?’” While this scene seems to ally Brandon and the rapists act as agents of a “natural order” which

with John and Tom as a man, it positions Lana, Can- dates back to Adam and Eve.

dace, and Kate at the other end of the object-specta- We may see this rape as the moment in which John

tor binary. Brandon and Lana are distinguished from and Tom castrate Brandon, thereby restoring his vagina

49

This content downloaded from 137.248.1.6 on Thu, 6 Aug 2015 06:55:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Oeffnung

as a female oriéce. In her book Gender

Trouble , Judith Butler describes the

vagina as “the site of masculine self-

elaboration . . . (which) means then to

reèect the power of the Phallus, to sig-

nify that power . . . to supply the site

at which it penetrates, and to [be] . . .

the dialectical conérmation of its iden-

tity.” 4 And if we assume, for a mo-

ment, the cruel logic of Tom and John,

and break down the categories of man

and woman to their functions in sexual

intercourse, then the rape repositions

everyone according to their “god-

given” gender. Brandon has a vagina,

so Brandon is a woman. Tom and John

penetrate his vagina, thereby reaffirm-

Looking at Lana . . .

ing themselves as men.

In an interview for Sight and

Sound, Kimberly Pierce described the rape scene of rather than a male “top” (note Brandon’s penis, which

Boys Don’t Cry as “four frame flashes viscerally has symbolically disappeared) and a female “bottom.”

knocking into you, like memory on consciousness.” 5 In Longing for Recognition, Butler critiques the élm’s

This is more than a simile, for the rape scene is staged ultimate unwillingness to accept “Brandon’s constant

as a memory knocking into consciousness, contrasted dare posed to the public (gender) norms of culture”:

with parallel cuts of the battered Brandon Teena (now

Brandon is no lesbian, despite the fact that the

Teena Brandon?) as a sheriff bullies him to re-narrate

élm, caving in, wants to return him to that sta-

the event. Metaphorically, the sheriff’s interrogation is

tus after the rape, implying in fact, that the re-

a second rape; it repositions Brandon as the object of

turn to (achievement of?) lesbianism is

violence, and again the agent of this assault is male.

som ehow facilitated by that rape, returning

The juxtaposition of Brandon’s “memory” of the orig-

Brandon, as the rapists sought to do, to a “true”

inal castration with this second castration is what “vis-

identity that “comes to terms” with anatomy. 6

cerally knocks into” the audience. During the sheriff’s

brittle questioning (“Where’d they try to pop it in érst Even while a lesbian love scene seems satisfying

at?”), we already see Brandon as a pathetic creature, in the sense that same-sex love-making subverts tra-

a suffering victim on whom to lavish our pity. Ges- ditional conceptions of gender and desire, we grow

ture is still his primary vehicle of communication; he suspicious of Brandon and Lana’s passive acceptance

expresses pathos by slum ping low in his chair and of Brandon’s “new” anatomy. Suddenly other charac-

shifting his eyes to the èoor, as though to indicate that ters describe Brandon with the “she” pronoun , and

his powerful male gaze has been extinguished. Bran- even replace the name “Brandon” with “Teena.” Only

don’s body no longer holds any promise for action, once does the film draw attention to Brandon’s new

for it has been doubly reconfigured as an object. At female identity, which essentially has been grafted onto

this point John, Tom, and the sheriff seize control of his “castrated” body, when Lana notices that Brandon

the action, thus reestablishing their power of agency. has re-styled his crew cut to look more “feminine.”

All three exercise force over Brandon, and then ex- Realizing the implications of Brandon’s gender trans-

ploit him as a counter-reference by which to assert mutation as an “achievement of lesbianism,” she sud-

their masculinity. denly hesitates to run away with him.

Submitting to the castration narrative by which The élm’s title seems ironic if we take it at face

Brandon is suddenly rendered female, the élm reposi- value, because Brandon is the “boy” who cries. But he

tions him as a pathetic character throughout the rest of only cries after the rape, as though John and Tom had

the élm. Following the rape, there is a love scene in succeeded in emasculating him. By implication, Bran-

which Brandon and Lana sleep together as two women, don’s tears symbolize his return to an essentialist no-

50

This content downloaded from 137.248.1.6 on Thu, 6 Aug 2015 06:55:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

tion of femininity. To understand this we must con- scene after his rape, Brandon locks himself in the bath-

sider the other weepers in Boys Don’t Cry, namely room, ostensibly to “clean himself up.” He begins to

Lana, Candace, and Lana’s mother. Tears create a har- smash his head against the bathroom wall and tear at

mony of womanly pathos between these characters, in- his hair with his fingers, desperate gestures of self-

dicating that the “castrated” Brandon is a sufferer, a reprobation. In a sudden turn, however, he sees himself

weeper, and therefore a “woman.” The title proves to in the mirror, and his eyes light up. “I’m gonna live!”

be more than a jeer; it resonates with the chilling he cries, and springs out the window, escaping in the

woman-as-pathos formula of melodrama. nick of time. This subversive action underscores the

The word pathos is particularly apt for the dead- pathos of victimization, and keeps us rooting for

ening scenes between the rape and death of Brandon Brandon.

Teena. And there is a sure contrast between the pro- The question then is how audiences will receive

tagonist’s pre- and post-rape personae. Before the rape the élm, whether ultimately Boys Don’t Cry stabilizes

he is a hero, a pro at bumper-skiing, girl-baiting, and our categories of gender, or whether it exhorts us to

beer drinking. After the rape he emerges as a pathetic counter-read these norms. While the polemic of gender

creature, in many senses far more “feminine” than be- displacement rarely fails to rouse viewers, some re-

fore. But that is to assign truth to the cliché of woman- sponses seem ambivalent. Many react to the film’s

as-pathos and man-as-action, which can’t be applied pathos, maintaining either that “Boys Don’t Cry just

to the entire élm. Pierce rebels against the old adage by depressed the hell out of me”8 or giving credence to

also giving her male villains the beneét of both pathos the “emotional savageness of . . . a great human

and action, showing that a single character can oscil- tragedy.” 9 The word tragedy is a specious recognition

late between masculine and feminine ways of being. of Brandon Teena. If we accept Brandon only after he

Katherine Monk writes of Tom and John, “In has been duly accused, convicted, and punished for

[Pierce’s] eyes John and Tom weren’t just rapists, transgenderism, then we ultimately submit ourselves to

homophobes, paranoid, self-mutilating, psychotic mur- the stièing “norms” of gender.

derers—heck, they’re people too.” 7 For example, Tom This unsettling conclusion resonates, for instance,

mutilates himself and wears his scars like battle with Hollywood’s treatment of Hillary Swank. B. Ruby

wounds. This “action” of striking against the self is an Rich writes, “The boyish Brandon transmutes back

expression of pain and helplessness that renders Tom again into sexy babe as Swank shows up in form-hug-

less “powerful” in the eyes of the audience. He says ging dresses, batting her eyes and thanking her hus-

to Brandon, “Some people punch holes in walls. I gotta band. The good news? That was all acting. The bad

control this thing inside me.” Similarly, John refuses to news? The same.” 10 Rich exposes the good and the

reduce himself to a Machiavellian guise of villainy. bad of Pierce’s élm. On the one hand, Boys Don’t Cry

His jealous rages throw a visceral punch at the audi- pays homage to the performative nature of gender, to

ence, and his spasms of sheer anger are undercut by a the idea that a sexed body can vacillate between gen-

pathetic sense of fatalism. In one scene, he exhorts der identities. In the élm’s multi-layered theater, Bran-

Brandon to pull off the highway to avoid a pursuing don’s masquerade was played out by Swank, who also

cop car, plunging them into an abysmal zone of dust had to reinvent herself in a generative process of gen-

and tumbleweed. After they are caught, John irra- der construction. Nonetheless, our culture’s neurosis

tionally blames Brandon for “almost killing them” and with regard to sex-gender symmetry demands ulti-

steals off in the car with Lana, as though to rectify him- mately that Brandon be castrated and re-positioned in

self by seizing possession of her. In this sense, John a female body. This occurs not only in the film, but

attempts to reinstate the gender binary by announcing also in the real-life reincarnation of Brandon Teena as

himself as a possessor of Lana—the male bastion who the “sexy babe” Hillary Swank.

exercises power over the womanly object. With con- The resolution? We must read Boys Don’t Cry with

sideration, however, for the pathos which underlies consideration to its gender-bending devices, and its du-

John’s angry spasms, Boys Don’t Cry indicates a degree alism of pathos and action. These tropes operate par-

of fallacy in the gender-derived mechanics of pathos ticularly with reference to the coexistence of “male”

and action. and “female” identity in the character of Brandon

This slippage between pathos and action is also Teena, whose “performance” is a useful point of de-

true for the rape victim, who can’t be described as parture for a critique of the cultural maxims of gender.

once-hero-now-damsel in a monolithic sense. In the Annalee Newitz writes that so-called gender-benders

51

This content downloaded from 137.248.1.6 on Thu, 6 Aug 2015 06:55:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

like Brandon are not “the dupes of gender, but pioneers Notes

in a new culture where gender is optional, not manda-

tory.” 11 This counter-reading may prove to be a chal- 1. Margo Jefferson, “When Art Digests Life and Disgorges

lenging project. Its Poison,” New York Times (February 21, 2000).

2. Gary Morris, “Hell in the Heartland,” Bright Lights no. 27

On a énal note, Kimberly Pierce writes, “A guy (January 2000). http://www.brightlightsélm.com/27/index.

friend said after seeing the movie that he so identiéed html.

with Brandon that he stood naked, holding his testi- 3. Kimberly Pierce, “Brandon Goes to Hollywood,” The Ad-

cles, staring at himself in the mirror, wondering if he vocate (March 28, 2000), pp. 44-46.

was a man or a woman.” 12 This quote evokes a sense 4. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subver-

sion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990).

of skepticism over the crude corollary between sex and 5. Danny Leigh, “Boy Wonder: Interview with Kimberly

gender. On the one hand, the man’s identiécation with Pierce,” Sight and Sound, vol. 10, no. 3 (March 2000),

Brandon is problematic, for he has been taught that pp.18-24.

men and women sit at opposite poles of a binary plane, 6. Judith Butler, “Longing for Recognition,” UC Berkeley:

that each sex category yields to a discrete locus of Departments of Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, 2000,

pp. 16-17 (unpublished).

meaning which is “gender.” We’ve always assumed 7. Katherine Monk, “Review: Boys Don’t Cry,” CBC Info-

that a woman is a woman, even in a crewcut and wran- culture, Yahoo! Movies, October 27, 1999, p. 2.

gler jeans. Evidently, Brandon Teena has violated these http://www.infoculture.cbc.ca/archives/élmtv/élmtv_10261

norms. The man identifies with Brandon rather than 999_boysdontcryreview.html.

condemning or even pitying him; in doing so he trans- 8. Film Geek, “Review: Boys Don’t Cry” January 6, 2000.

http://www.élmgeek.com/pages/boysdont.html.

gresses the cultural axioms of sex and gender. The next

9. James Bernadelli, “Boys Don’t Cry: A Film Review.”

step, of course, is for this man to accept his acceptance http://movie-reviews.colossus.net/master.html.

of Brandon, and to realize that gender categories are al- 10. B. Ruby Rich, “Queer and Present Danger,” Sight and

ways in èux. Sound, vol. 10, no. 3 (March 2000), p. 25.

11. Annalee Newitz, “Bad Review: Boys Don’t Cry,” Bad Sub-

Rachel Swan is an undergraduate student of Rhetoric jects, November 30, 1999, p. 2.

at the University of California, Berkeley. 12. Pierce, The Advocate, p. 46.

52

This content downloaded from 137.248.1.6 on Thu, 6 Aug 2015 06:55:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- X-Men Legends GuideDocument48 pagesX-Men Legends GuideFeliciano Nevarez RaizolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing A Compare Contrast EssayDocument5 pagesWriting A Compare Contrast EssayFatma M. AmrPas encore d'évaluation

- "REAL" Scream 4 ScreenplayDocument112 pages"REAL" Scream 4 ScreenplayLiam Jacobs100% (4)

- Film Bodies - Gender Genre ExcessDocument13 pagesFilm Bodies - Gender Genre ExcessEmmanuel MilwaukeePas encore d'évaluation

- The Guildsman 06Document56 pagesThe Guildsman 06JP Sanders100% (1)

- Script Analysis - The ExorcistDocument4 pagesScript Analysis - The ExorcistBrunoPas encore d'évaluation

- NYU International Film 60s-Present SyllabusDocument10 pagesNYU International Film 60s-Present SyllabusBrent HenryPas encore d'évaluation

- And Daisy Dod BreathlessDocument8 pagesAnd Daisy Dod BreathlessEmiliano JeliciéPas encore d'évaluation

- Little White Lies (Aug, Sept, Oct - 2018)Document100 pagesLittle White Lies (Aug, Sept, Oct - 2018)AtalasPas encore d'évaluation

- Coding and AI Workshop Teacher Registration (Responses) - Sheet11Document15 pagesCoding and AI Workshop Teacher Registration (Responses) - Sheet11Sahil DangiPas encore d'évaluation

- Farida Chishti On VolponeDocument14 pagesFarida Chishti On VolponeMinhalPas encore d'évaluation

- Clover, Men Women and Chainsaws, 3-20.PDF - BC3012WF11Document12 pagesClover, Men Women and Chainsaws, 3-20.PDF - BC3012WF11Sara CristinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Never The Sinner PDFDocument9 pagesNever The Sinner PDFPayam Tameh0% (5)

- FD No. MGNT No. Company Name NameDocument143 pagesFD No. MGNT No. Company Name NamePonmani KandanPas encore d'évaluation

- Aprwsea Members List: Emp ID Employee Name Designation Mobile No1 Mobile No2 Mail ID 1 Mail ID 2 DistrictDocument56 pagesAprwsea Members List: Emp ID Employee Name Designation Mobile No1 Mobile No2 Mail ID 1 Mail ID 2 DistrictSRINIVASARAO JONNALAPas encore d'évaluation

- Lawyers, Guns, and Money: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Music of Warren ZevonD'EverandLawyers, Guns, and Money: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Music of Warren ZevonÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- She Found it at the Movies: Women Writers on Sex, Desire and CinemaD'EverandShe Found it at the Movies: Women Writers on Sex, Desire and CinemaÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (4)

- Blaine (Book 1): A Dark Mafia Romance, #1D'EverandBlaine (Book 1): A Dark Mafia Romance, #1Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (6)

- By Continuing To Use This Site You Consent To The Use of Cookies On Your Device As Described in OurDocument8 pagesBy Continuing To Use This Site You Consent To The Use of Cookies On Your Device As Described in OurYashashavi LadhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bossy PantsDocument1 pageBossy Pantsakg2990% (1)

- BROOKER Joseph, The Wagers of Money, 2005, Law & LiteratureDocument25 pagesBROOKER Joseph, The Wagers of Money, 2005, Law & LiteratureWayne ChevalierPas encore d'évaluation

- Greasy Lake Thesis StatementDocument6 pagesGreasy Lake Thesis Statementlindseyriverakansascity100% (2)

- A Walk To Remember Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesA Walk To Remember Reaction PaperHamdy Pagilit DimaporoPas encore d'évaluation

- Theatre ReviewDocument2 pagesTheatre Review242shizumePas encore d'évaluation

- Monsters in Our Midst ReviewDocument4 pagesMonsters in Our Midst ReviewAndy TaylorPas encore d'évaluation

- Script AnalysisDocument3 pagesScript Analysisapi-314550470Pas encore d'évaluation

- Movie Review: PsychologyDocument4 pagesMovie Review: PsychologyMaisha MalihaPas encore d'évaluation

- Evans - Monster Movies - A Sexual TheoryDocument14 pagesEvans - Monster Movies - A Sexual TheoryTracy Lee WestPas encore d'évaluation

- The Exorcist - An AnalysisDocument4 pagesThe Exorcist - An AnalysisMateusz Buczko0% (1)

- 482 521 1 PBDocument9 pages482 521 1 PBTariq MehmoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis For Sonnys BluesDocument5 pagesThesis For Sonnys Bluestarasmithbaltimore100% (2)

- Film BodiesDocument13 pagesFilm BodiesRafaela Germano MartinsPas encore d'évaluation

- Bunch of Snake Freaks! A Brit's Take on Dead Pets, Sleazeballs and Other Fun Movie Stuff: Ice Dog Movie Guide, #5D'EverandBunch of Snake Freaks! A Brit's Take on Dead Pets, Sleazeballs and Other Fun Movie Stuff: Ice Dog Movie Guide, #5Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2014 Read and Watch GuideDocument2 pages2014 Read and Watch GuidelibertyliePas encore d'évaluation

- May McgorveyDocument12 pagesMay McgorveyAnamitra KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rhetorical Analysis - The CrucibleDocument2 pagesRhetorical Analysis - The Cruciblemira gPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Write Book SummaryDocument8 pagesHow To Write Book SummaryneelmazahoorPas encore d'évaluation

- AML 2001 AnnualDocument175 pagesAML 2001 AnnualAndrew HallPas encore d'évaluation

- Williams-Film Bodies Gender Genre and ExcessDocument13 pagesWilliams-Film Bodies Gender Genre and Excessyounes100% (1)

- American Beauty Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesAmerican Beauty Thesis Statementaflnoexvofebaf100% (2)

- Review - William Blake's Road of Excess': Demystifying The Cultural Iconoclasm of The Hell's AngelsDocument6 pagesReview - William Blake's Road of Excess': Demystifying The Cultural Iconoclasm of The Hell's AngelssirjsslutPas encore d'évaluation

- Julian Barnes Novels' Info: PulseDocument16 pagesJulian Barnes Novels' Info: PulseŞeyma ÇelenPas encore d'évaluation

- Screwball Paper2Document15 pagesScrewball Paper2erin_klingsberg100% (1)

- Internal ConnectionDocument5 pagesInternal Connectionbarbara.va.gonzalez.0412Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mere Anarchy: Dreams, Nightmares, Questions, and FuturesD'EverandMere Anarchy: Dreams, Nightmares, Questions, and FuturesPas encore d'évaluation

- Water Pollution EssayDocument8 pagesWater Pollution Essayb725c62j100% (2)

- The Road Is A Novel That Was Written by Cormac Mccarthy and Was Published in The YearDocument11 pagesThe Road Is A Novel That Was Written by Cormac Mccarthy and Was Published in The YearRosanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nor Mag Is 1Document26 pagesNor Mag Is 1mikey59Pas encore d'évaluation

- Monster As A Superhero An Essay On Vampi PDFDocument10 pagesMonster As A Superhero An Essay On Vampi PDFJaime VillarrealPas encore d'évaluation

- Greasy Lake Thesis IdeasDocument7 pagesGreasy Lake Thesis Ideaskllnmfajd100% (2)

- Chance & Possibility: Seven Fantastical Tales of Gay DesireD'EverandChance & Possibility: Seven Fantastical Tales of Gay DesirePas encore d'évaluation

- Y No Se Lo Trago La Tierra ResumenDocument6 pagesY No Se Lo Trago La Tierra Resumenn1b0lit0wum3100% (1)

- Introduction to the Dreaming in Australian EthnologyDocument7 pagesIntroduction to the Dreaming in Australian EthnologyA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Encounters Pres M PDFDocument16 pages1 Encounters Pres M PDFA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Performative StrategiesDocument16 pagesPerformative StrategiesA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Society For Cinema & Media StudiesDocument17 pagesSociety For Cinema & Media StudiesA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 2 Sewlall Deconstructiong EmpireDocument15 pages9 2 Sewlall Deconstructiong EmpireA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Review of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the DesertDocument6 pagesFilm Review of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the DesertA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- 6,7,8 2 Contentious Absolutism, OlaoluwaDocument18 pages6,7,8 2 Contentious Absolutism, OlaoluwaA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Encounters Pres M PDFDocument16 pages1 Encounters Pres M PDFA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 1 Barker Escaping PDFDocument20 pages9 1 Barker Escaping PDFA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- The Rocky HorrorDocument9 pagesThe Rocky HorrorA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Royal Institute of PhilosophyDocument15 pagesRoyal Institute of PhilosophyA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Fat Spirit Obesity ReligionDocument15 pagesFat Spirit Obesity ReligionA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- StuartsDocument1 pageStuartsA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus - Gender ConfusionDocument5 pagesSyllabus - Gender ConfusionA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- TZLLHLL :1Q (Lflzallztllaq (Zet1 ' Ii Lilga 1geaii LZ Zezae: I Te L Ii (ZT/ - I::Ii Le I2T1TiDocument9 pagesTZLLHLL :1Q (Lflzallztllaq (Zet1 ' Ii Lilga 1geaii LZ Zezae: I Te L Ii (ZT/ - I::Ii Le I2T1TiA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Doing ResearchDocument5 pagesDoing ResearchA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Creationism ParagraphDocument1 pageCreationism ParagraphA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Reading Answers and Sentence PlacementDocument2 pagesEffective Reading Answers and Sentence PlacementA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluating A Text ChecklistDocument1 pageEvaluating A Text ChecklistA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Useful Vocabulary From Analysis ProgrammeDocument1 pageUseful Vocabulary From Analysis ProgrammeA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- ILSS II Week 4 by Gillian SchwarzDocument1 pageILSS II Week 4 by Gillian SchwarzA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading XIII - ProcrastinationDocument1 pageReading XIII - ProcrastinationA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Vocab Answers Reason and ResultDocument3 pagesVocab Answers Reason and ResultA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading: Discipline and Punishment: AnswersDocument1 pageReading: Discipline and Punishment: AnswersA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Bacigalupo Transgender PDFDocument18 pagesBacigalupo Transgender PDFA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.firstly 2.in Other Words 3.for Example 4.next 5.as It Were 6.lastly 7.in ConclusionDocument1 page1.firstly 2.in Other Words 3.for Example 4.next 5.as It Were 6.lastly 7.in ConclusionA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Speaking Tips & Tricks to Reduce AnxietyDocument1 pagePublic Speaking Tips & Tricks to Reduce AnxietyA_BaeckPas encore d'évaluation

- 300 Crore Club MoviesDocument9 pages300 Crore Club MoviesTushar SaxenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Great People Inspiring Teens!: LessonDocument2 pagesGreat People Inspiring Teens!: LessonDanyPas encore d'évaluation

- Film ArtsDocument29 pagesFilm ArtsRoselyn Estrada MunioPas encore d'évaluation

- Cast Away Movie Writing ExercisesDocument1 pageCast Away Movie Writing ExercisesCarolina SuárezPas encore d'évaluation

- Rec Res TGTDocument590 pagesRec Res TGTAmit Soni100% (1)

- Earth SpringDocument71 pagesEarth SpringsofkassPas encore d'évaluation

- Booking Confirmation Village CinemasDocument1 pageBooking Confirmation Village CinemasAkau Uzi VertPas encore d'évaluation

- The List of District Wise SRTP Training CentersDocument2 pagesThe List of District Wise SRTP Training CentersSRINIVASARAO JONNALAPas encore d'évaluation

- Student Name Number T Number T Number T Total Earntotal Max MarksDocument2 pagesStudent Name Number T Number T Number T Total Earntotal Max MarksSrinu SrinivasPas encore d'évaluation

- NB 2023 12 24 23Document108 pagesNB 2023 12 24 23Mahi SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Telephone 2014Document25 pagesTelephone 2014Abhijor KoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Confessions of A Feminist Porn ProgrammerDocument9 pagesConfessions of A Feminist Porn ProgrammerEMLPas encore d'évaluation

- Summer Nights - Alexia VersionDocument1 pageSummer Nights - Alexia VersionAléxia DinizPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Digital Theatres For BIG CINEMADocument8 pagesList of Digital Theatres For BIG CINEMAsmgmsPas encore d'évaluation

- MoanaDocument3 pagesMoanaDewanti MarwaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tamil Nilam-Patta TransferDocument2 pagesTamil Nilam-Patta Transferdineshmarginal0% (1)

- Bhaag DK Bose LyricsDocument4 pagesBhaag DK Bose LyricsTechnical KaushalPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualified GroupC 19-01-2023Document104 pagesQualified GroupC 19-01-2023Raj YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- WalkinDocument7 pagesWalkindoc purushottamPas encore d'évaluation

- Report ListDocument22 pagesReport ListAnand shrivastavaPas encore d'évaluation

- Registered Participant List for 21st Century Skills and other ProgrammesDocument3 pagesRegistered Participant List for 21st Century Skills and other ProgrammesLucky ErrojuPas encore d'évaluation

- 20230617133602-Generalcat WithcounselingscheduleDocument15 pages20230617133602-Generalcat Withcounselingschedulemanpreet13.uiamsPas encore d'évaluation

- Skylink Parametry LadeniDocument1 pageSkylink Parametry LadeniTestPas encore d'évaluation

- Cus4331 202305Document3 pagesCus4331 202305Ka Po ChanPas encore d'évaluation