Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Odyssey: Form The Foundation of

Transféré par

Arenz Rubi Tolentino Iglesias0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

18 vues6 pagesTitre original

the iliad

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

18 vues6 pagesOdyssey: Form The Foundation of

Transféré par

Arenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasDroits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 6

The Iliad (a song about Ilium, or Troy) along with its

companion epic theOdyssey form the foundation of

ancient Greek culture and address the extremes of

human experience through war and peace. Both epics

areprimary, or oral, epics that draw on an enormous

wealth of cultural stories in unified structures that we

attribute to the poet Homer, in eighth century B.C.E.

The epics are written in an unsentimental style:

the Iliad depicts the ambivalence of war in meticulously

accurate details. Both the nightmare of war and its

excitement find expression in the Iliad, just as

the Odyssey’s pages quest for a home, or a peace that

seems hard-won after the devastation of war.

“The Fury of Achilles,” Charles-Antoine Coypel (1737)

The subject of the Iliad is the rage of Achilles and the

consequences of that rage for both the Achaeans and the

Trojans. War effects not only the men who fight the

battles, but also the women and children whose lives are

then shaped by its outcome. War represents the worst

and, ironically, the best of humanity: ugly brutality and

terrible beauty. If you doubt this, look at the place

violence holds in our culture; films like The Matrix even

show violence as poetic: a graceful dance of destruction

that thrills the audience like little else. We both pity

with Hector and sympathize with Achilles; neither side

of the war holds all of our sentiments. The final

outcome of the war, then, becomes truly tragic: only one

culture can continue while the other is destroyed or

enslaved.

The Iliad’s participants are the nobility of both cultures,

or the aristoi: “the best people.” They are the hereditary

holders of wealth and power, and their decisions effect

all of the culture. For example, Agamemnon’s decision

to infuriate Achilles at the outset of the Iliad has lasting

effects on the Greek warriors during the last weeks of

the Trojan War. Like most epics, of which the Iliad is

really the definitive example, the action begins in

medias res, a few weeks before the end of a ten-year

campaign, with all of the epic’s traditional

accouterments. The Iliad poses questions, as will

the Odyssey, about the nature of political order and

what humans must do to maintain that vision and

structure. The initial contention in the Iliad is between

the Greek champion Achilles and the Greek commander

Agamemnon. Who has the stronger claim to right:

Agamemnon who has the hereditary position, or

Achilles, the one with merit? Ultimately does it matter?

When swords are drawn, reason becomes irrelevant.

“The Quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon,”

Giovanni Battista Gaulli

The Iliad is replete with the culture of men. Indeed, one

may argue that all wars since the beginning of time are

about men and what they want to control: state, wealth,

women. What will men do to maintain their view of

order and structure? What are the consequences of the

resulting pride, arrogance, destruction? In book one of

the Iliad, we discover that because of Agamemnon’s

refusal to relinquish Chryseis, Apollo has rained a

plague upon the Achaean forces. Because he is

eventually challenged by Achilles — who represents the

wishes of the rest of the men — Agamemnon decides to

claim Achilles’ prize (a girl named Briseis) to reassert

his authority and put Achilles in his place for his

challenge. Achilles shows cunning and restraint —

qualities that are usually associated with Odysseus — in

his argument with Agamemnon, while the latter rages

and rails like a wounded child. Yet, when Agamemnon’s

men take Briseis, Achilles, also child-like, begins to pout

by his ships, cries to his mother, and refuses to play the

war game anymore. This final decision precipitates the

death of many Achaeans, including Achilles’ friend

Patroclus. Achilles’ resulting rage ends with the death of

Hector in book twenty-two, and Achilles’ own

apocryphal death under the bow of Paris before the

war’s end.

The brutality of Achilles and its consequences are most

evident in Book XXII of the Iliad. Achilles’ rage blinds

him to anything but the death of Hector, the Trojan

champion that killed Patroclus in book sixteen. Replete

with epic similes of the hunt, book twenty-two

illustrates Hector’s own reluctance to do what he sees as

his duty to face Achilles, yet thinks only of himself and

what his people might think if he doesn’t face the Greek

killing machine (cf. ll. 108-156). Hector’s resolve is soon

shaken as he sees Achilles closing, bloody rage the only

thing that Achilles sees. Hector flees, but is soon tricked

by Athena into stopping to face Achilles, perhaps a

commentary on Hector’s need for companionship and

Achilles’ desire for only personal vengeance and

renown. Hector is mercilessly murdered in front of

Troy’s walls, like a fawn at the jaws of a lion.

“Andromache Mourning Hector,” Jacques-Louis David

(1793)

The death of Hector, then, is given a final cultural

context from Hector’s widow Andromache. She now

sees the demise of Troy, but personally she sees no

future for their son Astyanax. The death of the father,

then, is a weighty metaphor for the Trojans: the order

that they secured will soon be rendered useless by the

barbarity of war; the father’s death leads to the

destruction of social order. This theme will be taken up

in the Odyssey as well: what is the responsibility of the

son for maintaining order in the absence or death of the

father? As Andromache sees no future for Astyanax, life

does continue even after the carnage of war, yet a new

order is imposed on the losers — those who escape

death. This theme of continuity is also addressed by

Virgil in his Aeneid.

Is war, then, a necessary component of human life? Just

because it has been historically up until this point, are

we to be like Achilles who could not hear reason

through his bloody thoughts: “No truce / till one or the

other falls and gluts with blood” (XXII.313-14)? When

do we decide that war is better than order?

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Reflections on Homer's Iliad and Odyssey - Insight into these epic tales of war, heroism, and adventureDocument16 pagesReflections on Homer's Iliad and Odyssey - Insight into these epic tales of war, heroism, and adventureCyrus Buladaco GinosPas encore d'évaluation

- "The Iliad" (GR: "Iliás") Is An Epic Poem by The Ancient Greek Poet HomerDocument4 pages"The Iliad" (GR: "Iliás") Is An Epic Poem by The Ancient Greek Poet HomerChristine Castanos BanalPas encore d'évaluation

- Iliad Common Essay QuestionsDocument8 pagesIliad Common Essay QuestionsJohn Kenneath SalcedoPas encore d'évaluation

- IliadDocument2 pagesIliadAura GaheraPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Literature Themes of Religion, Morality and HistoryDocument32 pagesGreek Literature Themes of Religion, Morality and HistorykookiePas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad by Homer The Epic Poem.Document4 pagesThe Iliad by Homer The Epic Poem.cornejababylynnePas encore d'évaluation

- Illiad and OdysseyDocument7 pagesIlliad and Odysseyarina89Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Epic Features of The IliadDocument4 pagesThe Epic Features of The IliadmimPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Evaluation - IliadDocument10 pagesBook Evaluation - IliadJonavel Torres MacionPas encore d'évaluation

- Iliad Summary: Chryses Apollo Agamemnon Calchas Achilles BriseisDocument4 pagesIliad Summary: Chryses Apollo Agamemnon Calchas Achilles BriseisBryan S AnchetaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mythological Background of IliadDocument7 pagesThe Mythological Background of IliadPAULIE JULIEANNA FAYE MENESESPas encore d'évaluation

- Trojan War and AftermathDocument2 pagesTrojan War and AftermathSebastiánFuentesPas encore d'évaluation

- 30 Marker Warfare IliadDocument3 pages30 Marker Warfare Iliadcara chandlerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad SummaryDocument3 pagesThe Iliad SummaryBlesy MayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad and OdysseyDocument9 pagesThe Iliad and OdysseyMark Angelo M. BubanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad by Homer (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideD'EverandThe Iliad by Homer (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuidePas encore d'évaluation

- TheIliad (G1)Document2 pagesTheIliad (G1)Alshameer JawaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Troy SummaryDocument3 pagesTroy SummaryArmin OmerasevicPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Myths - AchillesDocument5 pagesGreek Myths - AchillesStephen GeronillaPas encore d'évaluation

- AchillesDocument15 pagesAchillesdonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad and The Odyssey HOMERDocument48 pagesThe Iliad and The Odyssey HOMERChristineCarneiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes 221022 030937Document10 pagesNotes 221022 030937John Jeric SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- (NOTES) Homer The Iliad (Book1) (1-11)Document5 pages(NOTES) Homer The Iliad (Book1) (1-11)K͞O͞U͞S͞H͞I͞K͞ K͞A͞R͞M͞A͞K͞A͞R͞Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Topics For The IliadDocument6 pagesThesis Topics For The Iliadafjrydnwp100% (2)

- A British Museum Spotlight Loan at The Ure Museum - Troy: Beauty and HeroismDocument21 pagesA British Museum Spotlight Loan at The Ure Museum - Troy: Beauty and HeroismElliePas encore d'évaluation

- Achilles vs Hector: Exploring the True Heroes of Homer's IliadDocument9 pagesAchilles vs Hector: Exploring the True Heroes of Homer's IliadNatasha Marsalli100% (1)

- The Significance of Guest-Friendship in Homer’s IliadDocument37 pagesThe Significance of Guest-Friendship in Homer’s IliadDD 00Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Fall of Troy (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)D'EverandThe Fall of Troy (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)Pas encore d'évaluation

- W.H. Auden's "The Shield of AchillesDocument2 pagesW.H. Auden's "The Shield of AchillesAgastya BubberPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of The IlliadDocument1 pageSummary of The IlliadoarismendiPas encore d'évaluation

- Epics by lalit panwarDocument3 pagesEpics by lalit panwararyanpanwar2021Pas encore d'évaluation

- An Epic Poem About The Trojan War, AnalysisDocument3 pagesAn Epic Poem About The Trojan War, AnalysisAngel O Cordoba RromPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad: A New Translation by Caroline AlexanderD'EverandThe Iliad: A New Translation by Caroline AlexanderÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (156)

- EPICDocument2 pagesEPICAna Kassandra L. HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Great Books Module 2Document15 pagesGreat Books Module 2LG Mica Adriatico GuevarraPas encore d'évaluation

- Fate Homers IliadDocument10 pagesFate Homers IliadmelaniePas encore d'évaluation

- Midterm Activity 1: Story Review For The Iliad I. Title: The IliadDocument5 pagesMidterm Activity 1: Story Review For The Iliad I. Title: The IliadMara BajoPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Lessons From The Trojan War (Academic Journal From Ebsco Host) )Document35 pagesLearning Lessons From The Trojan War (Academic Journal From Ebsco Host) )Syed Anwer Shah100% (1)

- Homer - S Illiad and OdysseyDocument9 pagesHomer - S Illiad and OdysseyJuliusMendoza100% (1)

- Achilleus (Emperor) Achilles (Disambiguation) : Uh-Kill IliadDocument1 pageAchilleus (Emperor) Achilles (Disambiguation) : Uh-Kill IliadAnassPas encore d'évaluation

- (Cambridge University Press) Pache Ed. (2020) - The Cambridge Guide To HomerDocument5 pages(Cambridge University Press) Pache Ed. (2020) - The Cambridge Guide To Homer최연우 / 학생 / 철학과Pas encore d'évaluation

- Drama Genre - Tragedy - 025227Document11 pagesDrama Genre - Tragedy - 025227Felix JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad - Homer's Epic of Achilles and the Trojan WarDocument31 pagesThe Iliad - Homer's Epic of Achilles and the Trojan WarIGnatiusMarieN.LayosoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Story of The MahābhārataDocument3 pagesThe Story of The MahābhārataRiri KimPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancient Greek Epics: The Iliad and The OdysseyDocument2 pagesAncient Greek Epics: The Iliad and The OdysseyLie Raki-inPas encore d'évaluation

- Contest in Western DramaDocument1 pageContest in Western DramaDenise NajmanovichPas encore d'évaluation

- IliadDocument5 pagesIliadNexer AguillonPas encore d'évaluation

- Compare and Contrast Homer S Iliad and Virgil S Aeneid EssayDocument2 pagesCompare and Contrast Homer S Iliad and Virgil S Aeneid Essayapi-321293070Pas encore d'évaluation

- Troilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideD'EverandTroilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuidePas encore d'évaluation

- The Progression of "Heroes" in Literature Since Classical TimesDocument2 pagesThe Progression of "Heroes" in Literature Since Classical TimesRachael MachadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Classical CompilationDocument11 pagesClassical CompilationPamela PenafloridaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iliad Cast of CharactersDocument4 pagesThe Iliad Cast of CharactersAirell Takinan DumangengPas encore d'évaluation

- The Epic Poem of Ancient Greece - The Iliad ExplainedDocument78 pagesThe Epic Poem of Ancient Greece - The Iliad ExplainedJoan Rose LopenaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2543 Journal SampleDocument2 pages2543 Journal SampleZyzel SoonPas encore d'évaluation

- Report (Iliad 3)Document4 pagesReport (Iliad 3)Mathew Lozano PadronPas encore d'évaluation

- The Wrath of Achilles and the Fall of Patroclus (35 characters)The proposed title "TITLE The Wrath of Achilles and the Fall of PatroclusDocument11 pagesThe Wrath of Achilles and the Fall of Patroclus (35 characters)The proposed title "TITLE The Wrath of Achilles and the Fall of PatroclusAiswariya DebnathPas encore d'évaluation

- Character Analysis - Heroes of Trojan WarDocument4 pagesCharacter Analysis - Heroes of Trojan Warastro haPas encore d'évaluation

- BAFBAN1 - Week 01, Presentation DeckDocument60 pagesBAFBAN1 - Week 01, Presentation DeckArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Rhbillpresentation 130104024436 Phpapp01Document58 pagesRhbillpresentation 130104024436 Phpapp01Arenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Computer For Small BusinessDocument21 pagesBasic Computer For Small BusinessArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Classification of Supply Elasticity of DemandDocument2 pagesClassification of Supply Elasticity of DemandArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Values FormationDocument31 pagesValues FormationArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Batangas HistoryDocument1 pageBatangas HistoryArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Hiv AidsDocument20 pagesHiv AidsArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Groups and Organizations: Types, Characteristics, LeadershipDocument20 pagesSocial Groups and Organizations: Types, Characteristics, LeadershipArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Family PlanningDocument34 pagesFamily PlanningArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Windows XPDocument48 pagesWindows XPArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Microsoft Word: Presented by Mrs. GoepfertDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Microsoft Word: Presented by Mrs. GoepfertRizkie PerdanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Intro ExcelDocument13 pagesIntro ExcelArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- PREAMBLEDocument5 pagesPREAMBLEArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Main AimDocument2 pagesThe Main AimArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Sad PresentationDocument10 pagesSad PresentationArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- PopulationDocument2 pagesPopulationArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Language and CommunicationDocument51 pagesLanguage and CommunicationArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Relational AlgebraDocument7 pagesRelational AlgebraArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- For The Course of Tourism Planning and DevelopmentDocument33 pagesFor The Course of Tourism Planning and DevelopmentArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- For The Course of Tourism Planning and DevelopmentDocument33 pagesFor The Course of Tourism Planning and DevelopmentArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Visual Basic Visual Basic Is ADocument8 pagesVisual Basic Visual Basic Is AArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Language and CommunicationDocument51 pagesLanguage and CommunicationArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Senator QualificationsDocument3 pagesSenator QualificationsArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Electromagnetic SpectrumDocument22 pagesElectromagnetic SpectrumArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- VariableDocument2 pagesVariableArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

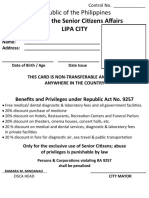

- Senior Citizen ID Card BenefitsDocument3 pagesSenior Citizen ID Card BenefitsArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Report in Hotel and RestaurantDocument88 pagesNarrative Report in Hotel and RestaurantAlvin Benavente75% (8)

- Pride and Prejudice: A. SummaryDocument12 pagesPride and Prejudice: A. SummaryArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- RH BillDocument1 pageRH BillArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Garipzanov2005 HISTORICAL RE-COLLECTIONS - REWRITING THE WORLD CHRONICLE IN BEDE'S DE TEMPORUM RATIONE PDFDocument17 pagesGaripzanov2005 HISTORICAL RE-COLLECTIONS - REWRITING THE WORLD CHRONICLE IN BEDE'S DE TEMPORUM RATIONE PDFVenerabilis BedaPas encore d'évaluation

- RH-067 Book Reviews - The Sri Lanka Journal of The Humanities. University of Peradeniya Vol. VIII NOS. Land 2, 1982. Published in 1985. Page 188 192Document5 pagesRH-067 Book Reviews - The Sri Lanka Journal of The Humanities. University of Peradeniya Vol. VIII NOS. Land 2, 1982. Published in 1985. Page 188 192BulEunVenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Journal of Cave and Karst Studies Information For AuthorsDocument3 pagesThe Journal of Cave and Karst Studies Information For AuthorsAlexidosPas encore d'évaluation

- Epic Satire - John DrydenDocument3 pagesEpic Satire - John DrydenAndrew ParksPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Well Tempered Sentence Elizabeth GordonDocument156 pagesThe New Well Tempered Sentence Elizabeth Gordonimanolkio100% (3)

- Resources On Holocaust Education and Literature For ChildrenDocument3 pagesResources On Holocaust Education and Literature For Childrensara8808Pas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary National ArtistDocument29 pagesContemporary National ArtistJoane PabellanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Romantic PeriodDocument40 pagesRomantic PeriodAntonio Jeremiah TurzarPas encore d'évaluation

- Muzzy 1 Part 1 Reading Learning Activities - AdvancedDocument5 pagesMuzzy 1 Part 1 Reading Learning Activities - Advancedapi-242075580Pas encore d'évaluation

- Huckleberry AnswersDocument2 pagesHuckleberry AnswersRita FaragliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sherlock Holmes FactsDocument4 pagesSherlock Holmes FactsМолдир КунжасоваPas encore d'évaluation

- CO Poe - CorrigéDocument2 pagesCO Poe - Corrigévanessa richardPas encore d'évaluation

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Quarter 1 - Module 5: Elements of A Short StoryDocument27 pages21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Quarter 1 - Module 5: Elements of A Short StoryHope Nyza Ayumi F. ReservaPas encore d'évaluation

- Amba NeelayatakshiDocument4 pagesAmba NeelayatakshiAswith R ShenoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Selected Poems by William Blake: I. From Songs of Innocence (1789)Document12 pagesSelected Poems by William Blake: I. From Songs of Innocence (1789)bensterismPas encore d'évaluation

- Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi's Self Inquiry - Explained.. - 2Document7 pagesBhagavan Ramana Maharshi's Self Inquiry - Explained.. - 2Charles Teixeira SousaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gulliver's Travels. Answer KeyDocument1 pageGulliver's Travels. Answer KeyOleg MuhendisPas encore d'évaluation

- Japanese TheaterDocument39 pagesJapanese TheaterJerick Carbonel Subad100% (1)

- ExistentialismDocument28 pagesExistentialismManasvi Mehta100% (1)

- ESMQ DR Renny Mclean Session 4 RecapDocument4 pagesESMQ DR Renny Mclean Session 4 Recapfrancofiles100% (1)

- English Year 5 SJKCDocument11 pagesEnglish Year 5 SJKCTricia HarrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Eakin Living AutobiographicallyDocument11 pagesEakin Living AutobiographicallyzeldavidPas encore d'évaluation

- GRADE 6 ENGLISH WORKBOOKDocument5 pagesGRADE 6 ENGLISH WORKBOOKjamesPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1 With SolutionDocument5 pagesAssignment 1 With SolutionAlva RoPas encore d'évaluation

- Poonthanam Nambudiri - WikipediaDocument17 pagesPoonthanam Nambudiri - WikipediaHemaant KumarrPas encore d'évaluation

- TTC The English Novel 11 Novelists of The 1840s The Brontë SistersDocument2 pagesTTC The English Novel 11 Novelists of The 1840s The Brontë SistersErwan KergallPas encore d'évaluation

- Konosuba - God's Blessing On This Wonderful World! TRPG - Natsume AkatsukiDocument165 pagesKonosuba - God's Blessing On This Wonderful World! TRPG - Natsume AkatsukishugoPas encore d'évaluation

- S.T. ColeridgeDocument12 pagesS.T. ColeridgeLisa RadaelliPas encore d'évaluation

- Read A Magazine or NewspaperDocument4 pagesRead A Magazine or Newspaperსო ფიაPas encore d'évaluation

- Poem Analysis of ThetisDocument12 pagesPoem Analysis of ThetisMitul HariyaniPas encore d'évaluation