Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Step Three Estimating Your Resource Requirements

Transféré par

Raja SekarDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Step Three Estimating Your Resource Requirements

Transféré par

Raja SekarDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Definition Step

Estimating

Three your Resource

Requirements

This Chapter of the Workbook explores the subject matter of estimating and looks to

ways in which you can ensure that the estimates you and your stakeholders make

are

as accurate and reasonable as

possible.

By the end of this Chapter, you will be able

to:

o Explain the purpose and benefits of

“estimating”

o Explain and demonstrate best practice approach to estimating the r

requirements

esource of your

o Project

Appreciate some of the jargon and standard terms used when

estimating and list some of the common pitfalls of

o Understand

estimating

o Explain how this information will be used in the planning

process

subsequentl

y

Where are we in the Project

Lifecycle?

o We have a Product Breakdown Structure, which lists all of the outputs

or

deliverables identified by our Project Team, that will lead to the

successful

delivery of the objectives of our

o Using

plan the PBS as a starting point, we have identified all of the activities

that

need to be carried out in order to create these products and documented

these

activities in a Work Breakdown

o WeStructure

now have a large sheet of brown paper, covered in Post-It notes that

summary

bear a of each activity and a unique reference number attributed to

each

one. We also have a key to explain each ref erence number and an

increasing

Assumptions Log that gives details of all of the assumptions underpinning

our

work to

date.

The next stage in the planning process is to determine how long each of

these

activities will take to carry

out.

There are a number of reasons why we now need to work out how long each

activity

will take:

o By adding up the durations we will have a very rough idea of how long

the

project will take from start to

finishestimated duration of each task will go some way to telling us how

o The

much

it will cost to

o Wecomplete

will be going on to schedule the tasks in the order they need to

completed and so it will help us to maximise the use of the time

be

available.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Estimating –a best practice approach

Throughout the rest of this Chapter, we will look at some of the issues

around

estimating and how to ensure that the estimates in your Project Plan are as

thought through as they can possibly

well

be.

If you read any text book or guide to estimating you will often find the

following

statement

:

There is no such thing as an

“accurate”

estimate – only “good” and “bad” .

ones

Therefore, this Chapter of the Workbook is about helping you and your Project

to ensure that your estimates are as “good” as

Team

possible.

We will look at the following

areas:

o Where to

start to improve the accuracy of your

o How

The distinction between “duration” and “effort” in

o estimate

estimating

o The challenge of estimating in an environment of

o Validating

deadlines your

estimates

o Accuracy

“Contingency

o tolerances

”

o Common traps and pitfalls of

o estimates

How to record your estimates in your planning

documents

Estimating –where to start

Clearly, there are going to be occasions where the duration of a task is

absolutely

certain and unequivocal. Where this is the case, no further debate is

required.

More often than not, however, you or your colleagues will need to use some sort

of

rationale to establish and later justify your estimates for how long a given task

will

take (and therefore cost). But where do you

start?

Unless the exact time that a particular task will take is clearly known in advance,

should start your estimates with a range of likely times, as they can reflect the

you

initial

uncertainty in mapping out the duration of each

task.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

To use a real life example, how long does it take to buy a house,

having your offer

from accepted, to moving

in?

Speak to colleagues or family too, as they may have had diff erent experiences to

your

own.

You should now have a range of durations for the house move. It is important

to

remember that the figures that each person you asked submitted will have

been

coloured by a number of

factors:

o Their own

experiences

o Location –there is a different house buying process in different

countries. their solicitor was a friend of

o Whether

theirs?

Having a range can be an effective tool for reflecting uncertainty, but ranges

limitations when applied to a project plan. If every task on your WBS was

have

given afor its duration, you could end up with a Project plan with an estimated

range

total

duration of between three weeks and 20

years!!

Therefore, you need to apply a logical process to your range, in order to nail it

to a specific figure for each activity. This figure is what we call a “Planning

down

Value” or

“PV

”

You obtain your Planning Values for each task by taking your range, which is

on optimistic and pessimistic assumptions about the duration (i.e. ‘best case’

based

and

‘worst case’ scenarios) and considering the underlying factors that shape the

estimate.

Thinking about the house move example from before, what could

go buying a house that could slow it

WRONG with

down?

Conversely, what could go RIGHT to speed things

up?

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Once you have weighed up all of the pros and cons, you should factor these into

original range estimate to establish your PV. The graph below demonstrates this

your

process

thought

.

Median (the value with as many

values below it as above it) Pessimistic

Optimistic

20 days 120 days

70 days

Cash buyer above

you in the chain

Survey delayed

Solicitor breaks leg

Mortgage is pre-approved

Planning value (79 days) Contract delayed

in post

We should emphasise that the examples given and the length of the lines

are

subjective –the process is more important here, the idea being that the PV you

at is less of a ‘finger in the air job’ than just picking somewhere along the

arrive

range

between the best case and worst case

scenarios.

This thought process should be undertaken with each activity in turn in order to

arrive

at figures that can be built into your

plan.

Improving the ‘accuracy’ of your estimates

Clearly, whilst the use of Planning Values is a more logical way to ensure that

the

estimates you use are as sound as possible, it would be a nightmare if the PM

was

expected to do this with every one of potentially hundreds (maybe thousands)

of

activities.

Some suggestions for techniques to improve the quality of your estimates

include:

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Consulting the ‘experts’ As with the compilation of the PBS and WBS, get

the people that are actually going to be doing the work to

do

the

estimates:

o They will know more about it than

o Theyyou will understand the constraints under

they will be operating, for example having

which

to

balance the project work with ‘doing their

day

job’

o They may have done something similar in the

o It pastwill help their commitment to the deadlines

they

that themselves are

Using your instinct Having a process setting

to follow should not stifle your

own intuition. What does your gut feeling tell you about

the

task or the

Comparing it with estimate?

Ever felt sometimes like you’re being asked to

experience

past reinvent

the

s wheel?

Refer to previous projects and their PM

Documenting records.

The quality of your estimate may depend on

your

assumption certain

assumptions, like the availability of a worker with

s aparticular

skill.

For example, an estimate for building a patio might

be

based on having a master craftsman to hand –if so,

sure you capture this so that you will understand

make

the

Time-Cost-Quality implications if you are given

an

apprentice to do the work

Referring to A instead.

classic example of this is ‘Please allow 28 days

conventions

or ‘rules of for

delivery’. Rules of thumb can be especially useful

thumb’ ifsomeone gives you an estimate that seems

wildly

optimistic, in that it allows you to challenge

the

assumptions behind it – “How confident are you

that estimate, given that it usually

about

takes...”

Of course, answer to this challenge may depend on

the

extent to which the person doing the estimate has

built

contingency into the duration –but more on

later

contingency

…

Remember at all times that we’re not looking for a perfectly accurate estimate –

there

is no such thing. An ‘estimate’ will by definition never be 100% accurate –merely

as

sound an estimate as we can get in the current

climate.

The distinction between “Effort” and “Duration”

You may have noticed that we have been referring to “duration” as the

of time in projects, rather than

measurement

“effort”.

The reason we refer to duration in project planning is clear –this is the actual

elapsed

time needed in order for each task to be completed to a given standard and

this is

therefore the figure that needs to be carried forward into a schedule that will

tell

howuslong the Project will take and when each task should

begin.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

This does not mean, however, that effort should be overlooked –in fact, it can

valuable

form a negotiating tool in relation to the Time-Cost-Quality triangle of

Project

your

…

Supposing your Sponsor tells you that your Project duration is too long, due to

other

considerations, and you need to make it shorter and suppose you have a task that

is

estimated to have duration of 20 days. The underlying effort of this task is also

20

man-days (i.e. there is no ‘please allow X days for delivery’ involved) and

estimate is based upon one person carrying it

the

out.

By doubling the available manpower, you can halve the duration of the task to

10

days (assuming that you maintain the same level of

productivity).

Of course, this additional resource may not be immediately available and

could

require you to buy in outside resource, like a consultant or subcontractor, to assist

the

person already earmarked for the job. Ther efore, although you are still paying

for 20

man-days, 10 of them will be dearer –hence the impact on your Time-Cost-

Quality

triangle

.

When putting together your estimates, it is good practice to use the back of the

Post-It

Notes to record the basis on which the duration figures have been arrived at

example,”20 days based on one competent person” or “10 daysbased on two

–for

experts

and one apprentice”. That way, if and when your durations are challenged or if

you

need to review your resource requirements, the information to back up your

decisions

is immediately

available.

The challenge of estimating in an environment of deadlines

The techniques we have talked about so far rely on one overriding assumption –

the PM has been given a free hand to schedule the Project, without any deadlines

that

or

time

constraints.

In reality this seldom is possible. –it is more likely that your Sponsor will come

to

you with a request with a deadline already

attached.

I’ve told our customer that the first batch of

300

mountain bikes will be ready for dispatch

in

three weeks – that won’t be a problem will

it..?

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Alternatively, the same could be true of budgetary

constraints…

I need you to organise this party for

500

people for me, but I can only let you have

baudget of £1000. I’m sure that will

be

enough…

.

Given that the imposition of deadlines and budgets is a fact of life, it is important

recognise an approach to estimating that will allow you to make the most of

to

the

available time and/or

money.

The ideal approach to estimating is what we call “Bottom Up” estimating, where

your

final total estimate of cost or time is a combination of all of the individual tasks

your Project plan. Doing so allows you accurately to define your Time-Cost-

within

Quality

triangle

.

“Bottom Up” estimating is a scientific method that ensures that tasks are

neither

omitted nor rushed and is seen to reduce the likelihood of cost or time overruns

implementing

in your

Project.

A “Top Down” estimate is one based on intuition rather than science –an

intuitive

assessment of the likely duration and / or resource requirements of the

project,

without exploring the underlying

tasks.

The comment above about the £1000 budget is a top down estimate, as in the

house

move example earlier in this Chapter. Knowing from past experience that it takes

79

days to move house might shape future

plans.

However, there are some disadvantages to “Top Down” estimating, such

as: o It could stifle choices and creativity – “I’d like to have table entertainers at

the

Party but I know we won’t have the budget for

o It it”could threaten quality, if checking mechanism are omitted in order to

save

time

o It is harder to build in contingency into your estimates in case things go

wrong

(we’ll talk about contingency later in the

o TheChapter)

people doing the estimates may feel that they are being pressurised

into

cutting corners, knowing that a budget or deadline is hanging over

them.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Advantages could

o It can serve as a ‘reality check’ to get people to focus on products

include:

and

activities that will add the maximum value to the issue at

o hand

Some people are motivated by deadlines and budgets and will therefore

see

them as challenges, rather than

obstacles

We should also bear in mind that budgetary limits and deadlines are a fact of

and very often cannot be ignored or swept under the

business

carpet.

A sensible strategy when given a deadline or budget which combines the

qualities of both, is to start off with a “Bottom Up” estimate, which is then

best

sense

checked by doing a “Top Down” based on the resource

available.

By doing both, you can approach your Sponsor with some real alternatives, based

on

the Time-Cost-Quality model – “With the time available, I can do this, this and

this.

However thisis what I can do with this much extra

, budget/time”

Of course this approach is going to take longer –but your Sponsor may appreciate

extra alternatives and insight

the

provided.

Validating your estimates

So far we have looked at the best practices about how to compile, improve and

‘sense

check’ your estimates, the basis on which they should be made and how to

balance

them against deadlines and budgetary

constraints.

We’ve mentioned that there is no such thing as an ‘accurate’ estimate –only

good

ones and bad ones –and so it is important to emphasise the need to validate

your

estimates.

The dictionary defines ‘valid’ as “sound, defensible, well-grounded” and

“validated”

thus a estimate is one that you should feel comfortable defending (or

perhaps

rationalising would be a better word to use) when challenged by your Sponsor or

any

other

stakeholder.

Many of the techniques you can use for checking the accuracy of your estimates

also be referred to when seeking to verif y or validate them

can

including:

o Referring to

experts with the people that are actually going to do the

o Checking

work of thumb

o Rules

o Your own instinct and gut

o Comparing

feeling the estimate with similar pieces of work done in the

past

The most important thing from the Project’s point of view is that the success

or

otherwise of the Project will depend on the quality of the estimate, and that you

owe

to theit rest of the Team (and business) to ensure that your estimates are more than

a ‘finger in the

just

air’.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Accuracy tolerances

A couple of times in this Chapter, you will have seen the following

quote...

There is no such thing as an

‘accurate’ estimate –only good

and

bad ones

No matter how much time you spend on deriving, checking and validating

your

estimates, it is inevitable that the final duration or outlay will differ from the

Despite this, your stakeholders will usually want to question you about the

plan.

supposed

‘accuracy’ of the figures you are

using.

There is an industry-wide accepted scale for how ‘accurate’ your

estimates are

expected to be at any given point in the planning

process.

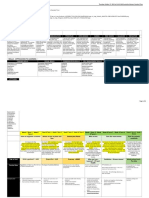

Accuracy Level Range Allowed When

Category ‘A’ 200% above final to 67% below

Appropriate

Feasibility

Category ‘B’ 100% above final to 33% below During Definition

Stage

Category ‘C’ Plus or minus 25% Once into Execution of

the Plan

The further you go into your plan the more accurate your estimate is likely to

The existence of this standard scale of accuracy helps PM’s to discuss their

be.

estimates

with their Sponsors and stakeholders and to negotiate with them over their

resource

requirements

.

This estimate

seems

a bit on the high

side….

Don’t worry, that’s

aCategory ‘A’ estimate

at

present, it may well be

once

lower I’ve had time

to

improve upon it.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

The terminology of the Categories is well known within the Project

community and should therefore help you to cement a professional relationship

management

your Sponsor and stakeholders. Conversely, if they don’t understand what you

with

mean,

you have a perfect opportunity to share your knowledge with

them!

Whatever terminology or sliding scales of accuracy you use, the key point to

make

here is that the further you progress through the planning pr ocess, the greater

understanding should be of the problem and therefore the soundness of your

your

estimates

should increase

accordingly.

“Contingency”

Whenever people are asked to estimate how long something will take or how

will

muchcost,

it there is an inbred temptation to cover themselves by building a bit of

leeway

into their

estimate.

The leeway is commonly known as

‘contingency’

Contingency is an allowance of spare capacity, either in time or money, which is

there

to cover you in the event of something going wrong during the implementation of

any

given task.

Real life examples include overtime budgets and overdraft facilities (there if you

them, but you’d rather not use them if you can help

need

it).

Contingency can clearly be very useful –after all, no one wants to have too

much

pressure on their time or budget – and it can have a positive effect on

people’s

perceptions of how you

operate.

Having some form of allowance is a good idea in any situation, but being

explicit

about the existence of leeway or contingency can have its

disadvantages.

For

o If your Sponsor knows that you routinely increase your estimates by

example:

an

arbitrary amount (15% to 20% is commonplace) he or she might tell you

to

take it out

o Ifimmediately

you come in well under your original estimate people may become

cynical

about the accuracy of your future estimates or may adjust their

you or of your

expectations team’s

o Ifperformance.

everyone in a particular work stream adds an arbitrary

amount of you could end up with a hugely overestimated overall dur

contingency

ation,

which could jeopardise the chances of the project being given the go-

ahead.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Ideally, by using the best case / worst case / Planning Value approach to

the original estimate, the figures should already have a degr ee of contingency

compiling

built

into them, based upon the likelihood of anything going wrong. If you then choose

to

flex your estimate to build in a little extra leeway, at least you have a firm grasp of

the

underlying basis of the estimate to fall back on –just as when selling a car, you

would

decide upon a realistic price that you would settle for, and then bump it up a little

to give you some room for manoeuvr

bit

e.

If someone else has done the estimate for you, it is a good idea to ask them

whether

they have built in any contingency and if so, how much –that way, if your

Sponsor

asks you to shave some time off the overall duration, you know wher e to

start.

It is important to bear in mind that having overt contingency isn’t necessarily a

bad

idea,

however.

Depending on the relationship with your Sponsor and stakeholders, you may be

to communicate the allowance in a way that establishes the benefits of the

able

existence

of the contingency to the Sponsor

–

“I’ve built in some spare capacity into

my

estimates, to reduce the likelihood of

having to report delays to you if things

me

don’t

go quite according to

plan”.

Some Project Managers acknowledge and indeed welcome the

existence of within the estimates given by their stakeholders and will use the idea

contingency

dividing up the “ownership” of it in order to manage it

of

proactively.

Ownership of contingency involves the PM in actively seeking out the

inherent

buffers, and pooling them together into a central ‘pot’ of time. If anyone’s task

over, the ‘pot’ of contingency is then deployed to cover the

runs

delay.

By doing this the PM is maintaining control over the schedule and is better able

to

understand the consequences of

delays.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

How to record your estimates in your planning documents

We mentioned earlier that the basis on which you (or your stakeholders) have

at the estimate should be documented. Many PM’s use the back of the Post-It

arrived

Notes

for this purpose, although it is equally possible to write it down in some

document

other

.

There is however, a standard requirement for where you record the actual

duration

that you have decided upon and this is at the bottom middle of the Post-It Note.

Thus

each Post-It note should look something like

this...

Task Description

Duratio

n

There is a very good reason why the duration needs to be recorded in that position

and

why you need to leave a gap around the edges of the Post-It

Note.

By the time you have finished your Project Plan, including scheduling each task

in

accordance with its duration and dependencies, there will be figures all the

around

way the edges of each Post-It Notes,

thus…

XXX XXX

XXX

Task Description

Reference

XXX Duration

XXX

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

The significance of these figur es will be explained fully in the next Chapter of

workbook –suffice to say for now that they relate to an invaluable technique

the

for

scheduling and prioritising within your plan called Activity

Networks.

Finally a brief word on how the times should be recorded. We’ve already stressed

that

the figure on the Post-It Note needs to be the duration of the task rather than

the

underlying effort. The standard practice is to record the duration in days, on

the

following

scale:

Measurement Equivalent

to…One day Six hours (the other hour is taken up with

breaks)

One week Five working

daysmonth Nineteen working days (the missing day(s) being the odd

One

day off work, Bank holidays, sick days

etc)

206 working days (similar to the above, the rest

One weekends,

being holidays, Bank holidays and a reasonable

year allowance

for sickness

absence)

Thus a project plan that is calculated with a total duration of 329 working days

should

take approximately nineteen months to

implement.

Case study –making some “good” estimates

Again we return to the Party for which you have been putting together the

PDD

Refer to the Post-It Notes that you have already done for your

which show Party,

the breakdown of tasks for some of the products you have

highlighted.

Using the techniques we have just discussed in the Workbook, pick a product

and

come up with some “good” estimates for each task, and thus an overall duration

for

the production of that

task.

Document any underlying assumptions, best case / worst case events, skill levels

on the back of the Post-It notes and then transf er the duration figure for each task

etc.

onto

the front of the Post-It Note as shown

above.

Use the space below to keep a permanent record of the exercise if you wish to do

so.

Toojays Training Consultancy Ltd © 2005

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Statement of Work (SoW) - A Guide To How To Write A Scope of WorkDocument63 pagesStatement of Work (SoW) - A Guide To How To Write A Scope of Workana.acreisPas encore d'évaluation

- Deep Dive Into Project Costs and Estimates (2021 Update) - 042323Document19 pagesDeep Dive Into Project Costs and Estimates (2021 Update) - 042323Joseph Kwafo MensahPas encore d'évaluation

- PMI Standard in Microsoft ProjectDocument33 pagesPMI Standard in Microsoft ProjectCristina CrdPas encore d'évaluation

- Is A Carefully Planned and Organized Effort To Accomplish A Successful ProjectDocument9 pagesIs A Carefully Planned and Organized Effort To Accomplish A Successful ProjectFatima VeneracionPas encore d'évaluation

- Project ManagementDocument10 pagesProject Managementmofiokoya olabisiPas encore d'évaluation

- Better GuesstimatingDocument3 pagesBetter GuesstimatingRakesh DhawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 2 B.ed Code 8605Document12 pagesAssignment 2 B.ed Code 8605Atif RehmanPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Successful Project Estimation TechniquesDocument10 pages6 Successful Project Estimation TechniquesHerman AbdullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Cost ManagementDocument13 pagesProject Cost ManagementZlatko JelovcicPas encore d'évaluation

- Capital Market Narrative ReportDocument27 pagesCapital Market Narrative ReportMarjorie ParaynoPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Management BookDocument13 pagesProject Management BookNahidul Islam100% (1)

- Project Constraints and AssumptionsDocument9 pagesProject Constraints and AssumptionsRaviram NaiduPas encore d'évaluation

- EstimationDocument26 pagesEstimationjerod85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Deep Dive Into The Project Schedule (2021 Update) - 033600Document20 pagesDeep Dive Into The Project Schedule (2021 Update) - 033600Joseph Kwafo MensahPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Steps to Map Business Processes & Improve EfficiencyDocument10 pages6 Steps to Map Business Processes & Improve EfficiencyMarcus FortePas encore d'évaluation

- Earned Value Management - Simple and Clear ExplainedDocument8 pagesEarned Value Management - Simple and Clear ExplainedrumimallickPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Charter Required For-Why We Are Doing For What We Are Doing (This Is The First Question of All Questions)Document33 pagesProject Charter Required For-Why We Are Doing For What We Are Doing (This Is The First Question of All Questions)Manish SonargharePas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Project Management SkillsDocument11 pages10 Project Management SkillsbdmckeePas encore d'évaluation

- PMIDocument47 pagesPMIavseqPas encore d'évaluation

- Total ControlDocument7 pagesTotal ControldemonicstratPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Cost Control: The Way It Works: by R. Max WidemanDocument6 pagesProject Cost Control: The Way It Works: by R. Max Widemanwdavid81Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Is A Scope of WorkDocument9 pagesWhat Is A Scope of WorkAmanuel KassaPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing a Project Schedule in 40 StepsDocument9 pagesDeveloping a Project Schedule in 40 StepsEle B AcPas encore d'évaluation

- Nama: Meilani Almira Putri: Kelas: Tbi 6C NIM: 1711230094Document5 pagesNama: Meilani Almira Putri: Kelas: Tbi 6C NIM: 1711230094almiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 2: Defining Project ScopeDocument35 pagesWeek 2: Defining Project ScopepiyushPas encore d'évaluation

- S - Curve PM Tool For EVADocument20 pagesS - Curve PM Tool For EVAAmit BelladPas encore d'évaluation

- Hands-On Activity: Create A Scope of WorkDocument9 pagesHands-On Activity: Create A Scope of WorkKiel RodelasPas encore d'évaluation

- Transcripts Agile Program Fundamentals 05 Discovery 3Document7 pagesTranscripts Agile Program Fundamentals 05 Discovery 3Scriba SPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Controls and Earned ValueDocument6 pagesProject Controls and Earned ValueAnonymous fE2l3DzlPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Initiation - Week 2,3,4Document37 pagesProject Initiation - Week 2,3,4piyushPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Management SkillsDocument15 pagesProject Management SkillsalidemohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- Logical FrameworkDocument38 pagesLogical FrameworkobahamondetPas encore d'évaluation

- Agile EstimationDocument32 pagesAgile EstimationRandy Marmer100% (1)

- Ebook - Information Technology Project Management Halaman-140-162Document23 pagesEbook - Information Technology Project Management Halaman-140-162Humairah Milleony TianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 5Document15 pagesChapter 5Muhammad ZafarPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.3 Project PlanDocument11 pages2.3 Project PlanManuela VelasquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Designing Software Estimates: June 18, 2020 Daniel VuDocument19 pagesDesigning Software Estimates: June 18, 2020 Daniel VuDaniel VuPas encore d'évaluation

- Estimating ChaosDocument7 pagesEstimating ChaosdiyyaprasanthPas encore d'évaluation

- Cost Estimating PHD PDFDocument28 pagesCost Estimating PHD PDFGeethaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Management: What We Need To KnowDocument17 pagesProject Management: What We Need To KnowCYNTHIANPas encore d'évaluation

- Agile Project Estimating - Agile 3PMDocument8 pagesAgile Project Estimating - Agile 3PMlongtruongPas encore d'évaluation

- Demystifying Story Points1 0Document4 pagesDemystifying Story Points1 0himanshu_414Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Final Project Justin Hall Arizona State University OGL 321: Project Leadership Dr. Christen Mann August 10, 2010Document8 pagesThe Final Project Justin Hall Arizona State University OGL 321: Project Leadership Dr. Christen Mann August 10, 2010api-561814825Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2005 AACE Transactions on Preparing a Basis of EstimateDocument5 pages2005 AACE Transactions on Preparing a Basis of Estimatediego_is_online0% (1)

- Analyze docs to uncover project tasksDocument53 pagesAnalyze docs to uncover project tasksMartinAlexisGonzálezVidalPas encore d'évaluation

- q023 Certificate Scenario Based Digital Assessment Learner Guide 0117.05 v6Document12 pagesq023 Certificate Scenario Based Digital Assessment Learner Guide 0117.05 v6Christine IreshaPas encore d'évaluation

- GSLC 1: Timothy Hutson 2001598464 Even NumbersDocument4 pagesGSLC 1: Timothy Hutson 2001598464 Even NumbersTimothy HutsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Applied Physics Project Proposals 220514 200158Document2 pagesApplied Physics Project Proposals 220514 200158Tanatswa MafundikwaPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing digital media projectsDocument5 pagesManaging digital media projectsshawn_jarrettPas encore d'évaluation

- Master 10 Project Management ProcessesDocument14 pagesMaster 10 Project Management ProcessesredvalorPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 Steps To Write A Scope of WorkDocument11 pages9 Steps To Write A Scope of WorksabumathewPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Management FundamentalsDocument9 pagesProject Management FundamentalsAdedire FisayoPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Strategies To Boost Software Deliveries - Wesley ZampelliniDocument37 pages5 Strategies To Boost Software Deliveries - Wesley ZampellinibytesombrioPas encore d'évaluation

- Five Ways To Evaluate Your ProjectsDocument2 pagesFive Ways To Evaluate Your ProjectsNick GenesePas encore d'évaluation

- Create a Project Budget in 7 StepsDocument5 pagesCreate a Project Budget in 7 StepsNoor ul huda AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Earned Value Analysis For The Rest of UsDocument6 pagesEarned Value Analysis For The Rest of UsSanjay Kumar SahPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Startup Guide ToolkitDocument16 pagesProject Startup Guide Toolkittrau-nuocPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF DownloadDocument3 pagesPDF DownloadRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- System Pro M Compact: DIN Rail Components For Low Voltage InstallationDocument6 pagesSystem Pro M Compact: DIN Rail Components For Low Voltage InstallationRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Very Fast Transient Overvoltages (VFTO) in Gas-Insulated UHV SubstationsDocument32 pagesVery Fast Transient Overvoltages (VFTO) in Gas-Insulated UHV Substationsjigyesh29Pas encore d'évaluation

- MIssile Cards Ebook PDFDocument23 pagesMIssile Cards Ebook PDFRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Writeup chsl17 T1 15062018Document1 pageWriteup chsl17 T1 15062018Raja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Very Fast Transient Overvoltages (VFTO) in Gas-Insulated UHV SubstationsDocument32 pagesVery Fast Transient Overvoltages (VFTO) in Gas-Insulated UHV Substationsjigyesh29Pas encore d'évaluation

- Appendix F: Connection and General Details: ElectricalDocument1 pageAppendix F: Connection and General Details: ElectricalRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Rock Fall Mitigation DesignDocument60 pagesRock Fall Mitigation DesignAparna CkPas encore d'évaluation

- Panel Instrument GuideDocument36 pagesPanel Instrument GuideRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Discrete Element Method (DEM) Numerical Modeling of Double-Twisted Hexagonal MeshDocument15 pagesDiscrete Element Method (DEM) Numerical Modeling of Double-Twisted Hexagonal MeshduongPas encore d'évaluation

- IBC Risk Category Table ExplainedDocument6 pagesIBC Risk Category Table ExplainedRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- MIssile Cards Ebook PDFDocument23 pagesMIssile Cards Ebook PDFRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 06 2016 Bhs Gs PDFDocument37 pages05 06 2016 Bhs Gs PDFRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- APRIL - TNPSC Current Affairs 2017Document54 pagesAPRIL - TNPSC Current Affairs 2017Raja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- EC2 Detailing of Slabs, Beams, Columns and FootingsDocument50 pagesEC2 Detailing of Slabs, Beams, Columns and FootingsArtjom SamsonovPas encore d'évaluation

- JournalsDocument142 pagesJournalsRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- SSC CHSL 2017 Tier 1 Cut Off Write-UpDocument3 pagesSSC CHSL 2017 Tier 1 Cut Off Write-UpTopRankersPas encore d'évaluation

- TNPSC General English Study Materials PDF - WINMEENDocument7 pagesTNPSC General English Study Materials PDF - WINMEENRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- BOQ SampleDocument23 pagesBOQ SampleQazi Abdul MajidPas encore d'évaluation

- 7509Document8 pages7509Raja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 06 2016 Bhs Gs PDFDocument37 pages05 06 2016 Bhs Gs PDFRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- General English - Famous Quotes - Who Said This - TNPSC Study PortalDocument8 pagesGeneral English - Famous Quotes - Who Said This - TNPSC Study PortalRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Beam Design Formulas With Shear and MomentDocument20 pagesBeam Design Formulas With Shear and MomentMuhammad Saqib Abrar100% (8)

- Notification Military Engineering Services Mate Civil Motor Driver and Other PostsDocument44 pagesNotification Military Engineering Services Mate Civil Motor Driver and Other PostsKaranGargPas encore d'évaluation

- Beam Design Formulas With Shear and MomentDocument20 pagesBeam Design Formulas With Shear and MomentMuhammad Saqib Abrar100% (8)

- Blank BoQ Small Industrial BuildingDocument20 pagesBlank BoQ Small Industrial BuildingRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Beam Design Formulas With Shear and MomentDocument20 pagesBeam Design Formulas With Shear and MomentMuhammad Saqib Abrar100% (8)

- Gowtham New ResumeDocument3 pagesGowtham New ResumeRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lok AdalathDocument2 pagesLok AdalathRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- First Floor PlanDocument1 pageFirst Floor PlanRaja SekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Cisco Catalyst Switching Portfolio (Important)Document1 pageCisco Catalyst Switching Portfolio (Important)RoyalMohammadkhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Re Factoring and Design PatternsDocument783 pagesRe Factoring and Design PatternsEvans Krypton Sowah100% (5)

- Executive MBA Placement Brochure of IIM Bangalore PDFDocument48 pagesExecutive MBA Placement Brochure of IIM Bangalore PDFnIKKOOPas encore d'évaluation

- cs2071 New Notes 1Document34 pagescs2071 New Notes 1intelinsideocPas encore d'évaluation

- Pinza Prova 5601Document2 pagesPinza Prova 5601Sublimec San RafaelPas encore d'évaluation

- Orace Rac TafDocument4 pagesOrace Rac TafNst TnagarPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice Exam - CXC CSEC English A Exam Paper 1 - CaribExams2Document6 pagesPractice Exam - CXC CSEC English A Exam Paper 1 - CaribExams2Sam fry0% (1)

- Al Washali2016Document17 pagesAl Washali2016tomi wirawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Explosion Proof Control Device SpecificationsDocument12 pagesExplosion Proof Control Device SpecificationsAnonymous IErc0FJPas encore d'évaluation

- Manufacturing Technology Question Papers of JntuaDocument15 pagesManufacturing Technology Question Papers of JntuaHimadhar SaduPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4 Wastewater Collection and TransportationDocument8 pagesChapter 4 Wastewater Collection and Transportationmulabbi brian100% (1)

- Digital Vision Installation PDFDocument2 pagesDigital Vision Installation PDFnikola5nikolicPas encore d'évaluation

- Gulf Harmony AW 46 Data SheetDocument1 pageGulf Harmony AW 46 Data SheetRezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1: Introduction: 1.1 The Construction ProjectDocument10 pagesChapter 1: Introduction: 1.1 The Construction ProjectamidofeiriPas encore d'évaluation

- Spare Parts List: Hydraulic Breakers RX6Document16 pagesSpare Parts List: Hydraulic Breakers RX6Sales AydinkayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Classful IP Addressing (Cont.) : Address Prefix Address SuffixDocument25 pagesClassful IP Addressing (Cont.) : Address Prefix Address SuffixGetachew ShambelPas encore d'évaluation

- Hytherm 500, 600Document2 pagesHytherm 500, 600Oliver OliverPas encore d'évaluation

- Wet Scrapper Equipment SpecificationDocument1 pageWet Scrapper Equipment Specificationprashant mishraPas encore d'évaluation

- MGI JETvarnish 3D EvoDocument6 pagesMGI JETvarnish 3D EvoSusanta BhattacharyyaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2019 Planning OverviewDocument7 pages2019 Planning Overviewapi-323922022Pas encore d'évaluation

- Iphone 6 Full schematic+IC BoardDocument86 pagesIphone 6 Full schematic+IC BoardSIDNEY TABOADAPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual de Teatro en Casa Nuevo PanasonicDocument56 pagesManual de Teatro en Casa Nuevo PanasonicMiguel Angel Aguilar BarahonaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3AH4 Breaker Cn (油品 P26)Document29 pages3AH4 Breaker Cn (油品 P26)kokonut1128Pas encore d'évaluation

- Catalog Filters PDFDocument53 pagesCatalog Filters PDFAlexandre Hugen100% (1)

- High-Temp, Non-Stick Ceramic Cookware CoatingDocument3 pagesHigh-Temp, Non-Stick Ceramic Cookware CoatingTomescu MarianPas encore d'évaluation

- Selecting Arrester MCOV-UcDocument9 pagesSelecting Arrester MCOV-Ucjose GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- IWWA Directory-2020-2021Document72 pagesIWWA Directory-2020-2021venkatesh19701Pas encore d'évaluation

- OSN 6800 Electronic DocumentDocument159 pagesOSN 6800 Electronic DocumentRashid Mahmood SajidPas encore d'évaluation

- AeDocument12 pagesAeRoberto SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Coaxial CablesDocument1 pageComparison of Coaxial CablesAntonis IsidorouPas encore d'évaluation