Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Collaboration Wave

Transféré par

Lewis J. PerelmanCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Collaboration Wave

Transféré par

Lewis J. PerelmanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Collaboration Wave

From Human Capital to Relationship Management

Lewis J. Perelman

Introduction

Author and editor Tom Stewart offered the “modest proposal,” in his Fortune column in

early 1996, that the time had come for companies to “blow up” their Human Resources

departments. Stewart concluded:

HUMAN RESOURCES has come to the proverbial fork in the road. One path leads

to a highly automated employee-services operation handling what used to be

paperwork in a ragingly efficient way. This function becomes little more than a

gateway to outside suppliers, impersonal in one sense but highly amenable to

supporting personalized, cafeteria-style services. The other leads straight to the

CEO's office.

Stewart cited studies showing that the majority of HR departments’ time and staff were

occupied in paper-intensive ‘administrivia’ for such elementary functions as payroll,

benefits, and recruiting. And, he argued, such tasks clearly could be handled far more

productively with software, online services, and outsourcing.

At the time, HR staffers were inflamed by Stewart’s broadside. The Society for Human

Resource Management prompted its 80,000 members to flood Fortune with protest letters.

Five years later, passions have cooled. As a recent study from the Knowledge Capital

1

Group shows, a substantial market has developed for the sorts of software, online, and

outsource solutions Stewart advocated. InternetWeek has reported that, in some cases,

HR departments actually are pushing deployment of such solutions ahead of their

suppliers. A variety of ‘e-learning’ and related ‘knowledge management’ solutions similarly

are in growing demand.

HR professionals now seem more likely at least publicly to advocate automating,

offloading, and downsizing many traditional, routine administrative functions. Some even

may boast of reducing overhead and shrinking HR staff headcount. Some of the more

enterprising HR leaders argue that their professional status is enhanced by being less

labor-intensive, less bureaucratic, and more ‘strategic.’ Today, more HR professionals

would rather be known as ‘performance consultants’ than simply personnel administrators.

And trainers similarly like more often to be seen as the ‘guide on the side’ rather than the

‘sage on the stage.’

1

Britton Manasc, William S. Hopkins, and Lewis J. Perelman, KCG MarketView: Human Capital Management

Solutions. Austin, TX: Knowledge Capital Group, Inc., 2001.

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 1 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

Nevertheless, these trends so far add up to less than a revolution, or even a

transformation of business-as-usual. Across the business landscape, the practices and

roles of HCM are yet highly uneven. Tom Stewart says that today, while the HR

community is more likely to invite him to lecture than to attack him as a bogeyman, “there

are still a lot of bureaucratic HR departments and staff out there.”

David Owens, chief knowledge officer at The Saint Paul Companies, feels that the HR

group in his company has been ahead of the pack in becoming both more efficient and

more strategic. Every year, SPC does a detailed performance evaluation of some 2,000 of

its managers worldwide. Two years ago, Owens notes, that was still a time-consuming,

often exhausting manual process; now “it is all done online.”

Moreover, Owens reports that the HR leadership at The Saint Paul Companies works

closely with the CEO, collaborates effectively with the information technology group, and

leads a ‘knowledge management’ effort that emphasizes collaborative learning. In all

these regards, however, Owens admits that SPC is still “unusual.”

Offloading 'administrivia' and downsizing HR staff may provide the potential for

remaining HR pros to take on a more strategic role. However, Sarah Bridges, a

Minneapolis psychologist with broad experience in recruiting and HR management for

Fortune 500 companies, cautions that not all HR staffers necessarily are prepared or even

inclined to perform a more strategic function. Also, Bridges warns that rapid payback of

HR automation is not guaranteed:

Depending on the particular company, and

the vendors, there may be substantial

What still seem scarce are solutions that

costs in the transition to a new system of

effectively change the shape of organizational HR administration.

designs, and that fundamentally alter how

people work with other people. The contending forces of social innovation

and bureaucratic inertia behind these

short-range observations have long historical roots. The hope that technology can liberate

human potential and energize social collaboration has been continually disappointed by

the stubborn persistence of authoritarian control.

The HCM solutions in today’s market so far seem to be lubricating the machinery of

organizational management to an extent that ranges from trivial to productive. What still

seem scarce are solutions that effectively change the shape of organizational designs,

and that fundamentally alter how people work with other people.

The basic question, as we ponder the future of this field, is whether a real structural

breakthrough may be, finally, on the horizon. To answer that, some historical perspective

may help.

Yesterday and today: the Inventory Paradigm and its discontents

In 1953, John Diebold, a new MBA graduate of the Harvard Business School, published

the results of his studies of the recent transformation of American industry in a book

entitled Automation—the first introduction of that term into popular use. Today, the term

‘automation’ is so shopworn that it is hard to recall that when Diebold coined it a full half-

century ago, it was ‘the next big thing.’

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 2 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

Nevertheless, a current reader of Diebold’s book may find much of its central message

surprisingly—and perhaps sadly—familiar. Diebold warned that industrial leaders and the

public generally were overly entranced with the startling powers of computer-based control

devices and systems. “Paradoxically,” Diebold wrote, “the current obsession with the

novelty and spectacular performance of automatic control diverts attention from the

problems of their application to industry.”

Introducing computers to factories and offices might be necessary, Diebold cautioned, but

was not sufficient to automate a business effectively: “The full promise of the new

technology cannot be realized so long as we think solely in terms of control.”

While he understood the popular bedazzlement with advanced information technology,

Diebold argued that it was a costly mistake to think that ‘automation’ was simply about

doing the same old business more efficiently. Both in office and factory, he said, it was

critical “to avoid the mistake of decorating obsolete processes with new gadgets.”

Particularly relevant to our study of current HCM solutions, he added this: “To use the

new technology as a speedier means of preparing the same reports that are now

prepared and to treat their contents in the same way they are now treated would be a

great mistake.”

In sum, Diebold stressed that ‘automation’ was not simply a matter of doing business the

same way with more efficient technology. Rather, he urged that capturing the potential

benefits of automation really required what he called “rethinking” of whole systems:

creating new kinds of products and processes, new kinds of management and

organization, new kinds of work for a new kind of workforce, and ultimately reshaping

industries, economies, and human societies.

Bureaucracy and the machine

Humanity’s often vexing dilemmas of technology and bureaucracy are ancient. As soon as

human technology became sufficiently productive to permit civilization to take root, there

came both the opportunity and the need for people to occupy diverse roles other than

simply feeding and procreating. Specialization, organization, and some kind of

management became essential.

It’s a safe bet that as soon as communities became too big for anyone to remember

everyone, someone decided to ‘take attendance.’ Ancient civilizations from Babylon to

Egypt to China did census surveys to get information about their human inventory for one

reason or another: taxes, military conscription, or of course, labor. Throughout most of the

history of human civilization, aristocracy was the common form of socioeconomic

organization, and various forms of slavery and serfdom gave ‘human capital management’

a literal reality.

th

In the late 19 century, the sociologist Max Weber lauded bureaucracy as a more liberal

and productive alternative to aristocracy. Aristocracy gave a few persons power to

manage and control other people on the basis generally of social status and inheritance.

As Weber saw it, bureaucracy’s advantage is that it allocates authority to whoever

demonstrates the necessary competence on the basis of superior knowledge.

While Westerners tend to identify bureaucratic organization with the industrial age,

bureaucracy’s roots go back some 2,000 years earlier to the Han Dynasty of China. The

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 3 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

Han Empire replaced feudal governance with a meritocratic civil service, hierarchically

centralized in the imperial capital. Consistent with Weber’s model, the ‘mandarins’ of

China’s civil bureaucracy were recruited from the empire’s broad (male) population,

trained in special academies, and selected for office by competitive examination.

There is an important difference in the bureaucracy of ancient China and that of the

modern, Western industrial state. The knowledge required for initiation to the mandarin

bureaucracy was primarily of Confucian philosophy, whose content focused on an ethical

code aimed at maintaining a harmonious social order. But the managers of industrial

bureaucracy were empowered for their know-how—that is, knowing how to get things

done productively.

While the practice of inventorying and managing human capital may be as ancient as

Egyptian pyramid building, the concept of ‘human capital’ or ‘human resources’ or

‘personnel’ as concrete factors of production and the concept of ‘management’ as a

rational professional discipline are recent inventions of the industrial economy. Consultant

William Bridges points out that the words ‘job’ and ‘employment’ only recently took on their

th

current economic meaning. Even in the 19 century, ‘job’ or ‘employment’ referred only to

a task a person happened to be doing temporarily, rather than the current notion of a long-

term bureaucratic position that a person is hired into on the basis of some demonstrated

qualifications.

Historians mark the dawn of the modern form of bureaucracy with America’s 1883

Pendleton Act, which established a professional civil service system to replace the

increasingly corrupt system of government by political patronage. Building on practices

started in the reign of Napoleon, France also elaborated its extensive civil service system

th

in the late 19 century.

Inspired by the civil service, the idea of ‘personnel management’ as a formal discipline

th

began to infiltrate industry at the turn of the 20 century. The first corporate office of

‘employment’ was established at the B.F. Goodrich Company in 1900. Professional and

industry associations for ‘personnel administration’ soon formed.

th

Also at the beginning of the 20 century, the most renowned proponent of ‘scientific

management,’ Frederick Winslow Taylor, pioneered the management of work and workers

as a rational, technical discipline. Frank Gilbreth and his wife Lillian famously started to

measure the performance requirements of each industrial ‘job’ with stopwatch and

yardstick. These innovations promoted the redesign of jobs for maximum efficiency—as

integral components of a comprehensive production machine.

Many were delighted with the popular wealth Taylorism delivered. Many people also were

dismayed by the grueling subordination of human needs to mechanical efficiency.

Artists and social critics satirized the ‘de-skilling’ and ‘de-humanizing’ of labor that seemed

to result from the rigor of industrial processes and the cold-hearted logic of scientific

management. Filmmaker Fritz Lang envisioned humanity reduced to a slavish army of

industrial ‘robots’ in Metropolis while Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times memorably depicted

the helpless little guy literally rendered to fit the gears of the enormous industrial gearbox.

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 4 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

Re-humanizing work

Such ambivalence about the power of technology both to liberate and to tyrannize

humanity is at least as ancient as the myth of Prometheus. The advent of the Industrial

Revolution inevitably spawned an ongoing series of Luddite rebellions against the

perceived dictatorship of the machine.

As the industrial age matured, however, a different form of counter-movement evolved,

one aimed less at overthrowing the industrial machine and more at humanizing it. Political

populism undertook to tame the excesses of industrial oligarchs with varying degrees of

government regulation. And labor unions formed to provide a balance of power between

the two arch classes of industrial bureaucracy, ‘management’ and ‘labor.’

The social contract emerging from such liberal reforms gave the ‘working class’ as a

population better compensation for their often mindless obedience to the tedious

requirements of the Taylor paradigm of industrial engineering: more job security, more pay

and fringe benefits, reduced working hours, and better protection of health and safety.

What such reforms mostly did not do was fundamentally alter the Taylorist form of process

design, or the theory of efficiency on which it was grounded.

th

By the middle of the 20 century, however, an alternative paradigm of ‘scientific

management’ gradually emerged to challenge the legitimacy of the Taylorist model on its

own grounds—productivity—but rooted

more in social science and psychology than

mechanical engineering. The engineers

themselves actually planted the seed of this

new movement with the discovery in the

1930s, in the U.S. aircraft industry, of what

they called the “experience curve.”

Profitability in aircraft manufacturing

depended greatly then (now, too) on the

ability of industrial engineers to project, from

Source: Computerworld, July 2, 2001

the cost data of a prototype, what the unit

cost of a new airplane will be once it goes

into mass production. Examining a mass of production data, engineers discovered that the

cost of producing each airplane fell steadily, along a pleasingly regular and consistent

curve, as the cumulative number of units produced grew. Even more remarkable: the

basic shape of the cost curve stayed the same no matter what particular kind of aircraft

was produced, or even whether the product was an airplane or a washing machine or a

radio.

Some management analysts went on to build prodigious consulting practices grounded

only on the quantitative implications of the experience curve. Mainly, they advised that

corporate strategy should seek the largest market share as quickly as possible, since the

experience curve assured that the company with the biggest volume of production would

have the lowest costs.

But others were more impressed with a different, human implication of the same curve:

Since, once started, the tools and process of the production system remained constant,

the only way productivity could be improving was that the people on the production line

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 5 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

must have been changing the way they work. And, since no one was ordering or training

them to do anything differently, they must have been learning from experience, and

changing the work themselves.

Inspired by the revelation of what was re-dubbed the “learning curve,” social scientists and

psychologists looked for, found, and then designed a growing body of cases showing that

more humane and democratic production designs not only made work more satisfying—

they resulted in substantially greater production and lower costs. At the same time that

Diebold was issuing his challenge to “rethink” automation, Eric Trist, Fred Emery, and

other scientists associated with the Tavistock Institute in London were developing a

counter to the Taylor theory of industrial management they called ‘sociotechnical systems

design’ (STS for short).

In parallel, W. Edwards Deming and Joseph Juran started to preach the gospel of ‘quality

control.’ Their message that companies needed to compete on product quality as well as

price fell on deaf ears in a booming America, but was taken to heart by Japanese industry.

The statistical methods Deming and Juran prescribed again flouted the Taylorist model:

They assumed that front-line workers were competent to measure and maintain product

quality. Moreover, Deming and Juran argued that the people in closest contact with the

production process had to be empowered with essential responsibility for quality control.

In a complete convolution of Taylorism, the presumption of STS, TQM, and similar mid-

century counter-movements was that front-line workers had brains, talent, and knowledge

that could greatly improve the production process, given a chance. But, to profit from this

resource, organizations needed to empower self-directed teams to participate fully in

planning and managing the production system. Gradually the idea dawned that—on the

threshold of what by the 1960s some were calling the ‘postindustrial’ economy—what

organizations really needed to manage was not human ‘resources’ or ‘capital’ but human

talent, communication, knowledge, learning, and collaboration.

Groundhog Day?

In the movie Groundhog Day, Bill Murray plays a man mysteriously trapped in a time

warp. Every morning when he wakes up, it is February 2 all over again. Repeatedly he

has to face the same events, the same problems, until he can find a solution to break the

cycle.

The history of the recurrent struggle over the last half-century to replace the Taylorist

pattern of industrial bureaucracy with a fundamentally different, more collaborative model

of human economic relationships too easily can leave us wondering if we are caught in a

similar plot. It seems that every decade or so, the same basic concepts of postindustrial

management are elaborated and reintroduced, often under a new label.

Quality control, disdained by

American management in the 50s,

It seems that every decade or so, the same retakes America by storm as Total

basic concepts of postindustrial management Quality Management in the 80s. The

are elaborated and reintroduced, often under a fascination with TQM wears off after a

new label. few years, is echoed in a passing

enthusiasm for ISO 9000, and then is

resurrected in the 90s under the

COLLABORATION WAVE people. PAGE 6 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

mantra of Six Sigma. Side roads branch off first into Benchmarking and later into a

fascination for Best Practices.

Diebold’s call in the 1950s to ‘rethink’ automation as a comprehensive system drew on the

contemporary interest in General Systems Theory. The latter led in the 1960s to Jay

Forrester’s System Dynamics modeling, which aimed to reveal why ‘complex’ systems like

corporations and cities tended ‘counterintuitively’ to resist command-and-control

management. Years later, one of Forrester’s disciples re-tuned System Dynamics as The

Fifth Discipline, which required that everyone learn “systems thinking,” which mandated

the Learning Organization, which in turn created a demand for new systems for

Organizational Learning.

After STS proved increasingly complicated to implement, Fred Emery re-launched it in

simplified form in the 1970s as Participatory Design. Empowerment, participation, and

teamwork bubbled up again in the 1980s’ search for ‘Excellence.’ When the quest for

excellence petered out in too many dry holes, STS was reincarnated once more in the

1990s as Reengineering.

But Reengineering became a widely used (or misused according to its champions) excuse

to downsize the workforce and crack the Taylor whip over the survivors. Then the urgency

for Reengineering faded in the euphoric glow of the Internet boom. To many it seemed

that the New Economy finally had arrived.

Recalling his earlier prophecy, Peter Drucker proclaimed in the past decade that this new

economy depended critically on empowered teams of knowledge workers doing

knowledge work. In rushed Knowledge Management gurus to harvest the tacit ‘intellectual

capital’ in workers’ heads and then to organize and archive it so that knowledge could be

shared with the whole company. Performance Support and Decision Support architects

would carve up the knowledge and electronically pump just enough, just in time, wherever

and whenever anyone needed it.

Finally, in the 1990s management gurus rediscovered general systems theory in the

newer, more computationally rich mathematics of Complexity and, naturally, applied the

lessons of complexity theory to organizational management. Enterprises, they said, are

complex social-technical ecosystems that require management to rethink ‘outside the box.’

The mathematics of ‘self-organizing systems’ such as schools of fish imply that workplace

teams cannot be commanded or organized but must be empowered to evolve as self-

directed communities of practice.

And so the pendulum has swung over the past five decades or more between contending

visions of the proper human relationship to the work, technology, management, and

organization of enterprise. Information technology has been entwined throughout this saga

as driving force, enabler, artifact, and sometimes nemesis.

The advice for transforming business today to meet the challenge of the information age

sounds hauntingly similar to that invoked for the automation age in the 1950s. After

reviewing this history, John Diebold was asked recently whether the lessons yet had been

absorbed, and the paradigm of business design yet had shifted. “I think,” he offered, “that

the Internet may prove, finally, to be the watershed.”

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 7 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

Perhaps so. Or is it still Groundhog Day? Whether it is or not will make an important

difference to which IT applications for the management of human talent and working

relationships succeed in the future.

Signs of breakdown and transformation

Let’s face it, no matter how sluggish bureaucracy may be to reflect it, the world has

changed in some dramatic ways since the Eisenhower Administration. The Cold War is

over—no small deal. Apartheid is gone; so are ‘Ma Bell’ and Pan Am. The political,

economic, and social roles of women are radically transformed. Tobacco is socially taboo.

The means of environmental protection may be debated but its desirability is rarely

questioned. The year 2001 hasn’t seen as much in the way of ‘space odysseys’ as

Hollywood once projected. But genetic technology today presents arguably far more

profound, unprecedented, and real challenges to the meaning of human existence.

Despite the pendulum swings of management and organization forms and reforms over

the past several decades, there’s no denying that the average workplace also has

changed tangibly since the 1950s. If a time machine could pluck a few people from typical

factories and offices of that age and drop them into similar slots in today’s world, certainly

they would notice a difference. Technology surely would dazzle them.

True, much about work and management and organization would appear quite familiar.

“There is a great dearth of design engineers capable of the advanced mathematics

necessary in much of the automatic control system work,” Diebold wrote in 1953, a

concern echoed in today’s hand wringing over perceived shortages of technical skills.

But organizational and social change would be noticeable, albeit that much would seem

more evolutionary than revolutionary. In the U.S., the social difference that probably would

most impress them would be the clearly more diverse and egalitarian workforce at all

levels. Most change in employment and the workplace likely would appear to be more in

degree than in kind: higher levels of education and training, greater and more flexible

benefits, more overt concern for employee health and family needs, broader participation

in stock ownership, greater emphasis on quality, the diminished role of unions, and

perhaps a sense of the greater globalization of markets.

As consultant Michael Hammer has pointed out, most organizations and institutions are

not designed to undertake fundamental change. If anything, they are designed to resist

basic change until they are confronted with overwhelming necessity—what The Godfather

called “an offer they can’t refuse.”

Today, the Internet bubble has burst, and what Federal Reserve Chairman Alan

Greenspan labeled “irrational exuberance” not so many months ago has been replaced by

a far more sober, even anxious mood. Oracles of brave new worlds and bold revolutions

do not seem timely. Especially when desperate investors—fed up with pampering spoiled

techno-brats and digital tycoons with signing bonuses, stock options, gold-plated perks,

and most recently, accounting sophistry—often are getting companies ‘back to basics’ with

a re-installment of ‘Chainsaw Al’ and ‘Neutron Jack’ management.

Nevertheless, the current distress itself may be symptomatic of the exhaustion and

breakdown of some conventional economic paradigms. Certainly the needs for different

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 8 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

ways of organizing work and business only have grown more urgent over the passing

decades, and may now truly be overdue. In any case, there are clear instances in the

present of some basic economic transformations that are both irreversible and irresistible.

Collaboration: theme of the decade

Napster is the poster child for the potent possibilities of new technologies to nurture both

communal and personal demands simultaneously—albeit in a way that also has tortured

the social order. Whatever the outcome of the legal and regulatory maneuvering around

Napster and similar ventures, the Napster type of peer-to-peer technology is forcing the

music industry to abandon an outworn business model, however reluctantly. And few

doubt that this model of decentralized, uncontrollable personal collaboration will soon

bulldoze many other businesses than just music.

EBay is another example of a ‘new economy’ venture that has forced a fundamental

transformation of commercial processes—again, by unleashing a new and paradoxically

impersonal form of personal collaboration, in this case to set prices and exchange goods

in a medium that is simplistically user-friendly and globally accessible.

These are but two of many possible examples—instant messaging, multi-user online

games, maybe even ‘reality TV’—of something big happening: Collaboration has

mushroomed in recent months as a critical theme affecting nearly every segment of the IT

2

market. And—notably, for the purpose of this report—it is a theme that intrinsically

begins and ends with people.

For the past decade, analyst George

Gilder has projected that the fusion of

Collaboration has mushroomed in recent ever-cheaper computational intelligence

months as a critical theme affecting nearly with broadband telecommunication would

every segment of the IT market. And it is a drive profound economic and social

change. The turbulence of this transition

theme that intrinsically begins and ends with is likely just another symptom of its

people. speed.

Until recently, telecommunication involved the horizontal exchange of information while

humans normally worked together in more vertically ‘stove-piped,’ hierarchical

people. But the gathering IT fusion of what Gilder calls the ‘microcosm’ and the

organizations.

‘telecosm’ are steadily changing the networked relationships among people—from co-

informing toward co-acting.

The Collaboration Wave may prove more powerful, maybe more daunting, than

‘globalization.’ Focused mostly at the macro level, globalization reflected growing

international intercourse among whole enterprises. While the Collaboration Wave today

seems often to be identified with business-to-business (B2B) commerce, it increasingly will

reflect the personalization and globalization of individual working relationships. “B2B has to

be rethought as H2H, that is human-to-human, for business collaboration to really work,”

says Jeff Crigler, co-founder of Engenia Software.

2

See Britton Manasco, William S. Hopkins, and Lewis J. Perelman, KCG MarketView: Collaborative Commerce

Solutions. Austin, TX: Knowledge Capital Group, Inc., 2001.

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 9 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

We can only guess exactly how these transformations will turn out. But the

telecommunications industry is one notable current indicator that basic changes are likely

in the design of enterprises and the mobilization of human talent.

At the moment, the telecommunications sector is in acute distress, battered by the

simultaneous obsolescence of technologies, regulatory policies, business models, and

organizational designs. The vestiges of the old ‘Ma Bell’ regulated monopolies are

decrepit, their ‘nothing goes’ culture repelling creative talent with bureaucratic inertia, and

maneuvering turbulent markets with the agility of an overloaded supertanker.

But after the crash of Internet euphoria, the ‘anything goes’ culture of the new-media

entrepreneurs has been widely obliterated. While some of the Internet start-ups took

advantage of a clean slate to try unorthodox ways to employ and organize talent, most of

the alternative models proved no more sustainable than the businesses on which they

were built. And the founders of many of the new ventures, obsessed more with building a

‘disruptive’ technology than a durable business organization, had as generic an interest in

HCM ‘solutions,’ as they did in furniture rental or janitorial service.

This pattern in the telecom sector suggests that neither stick-to-your-knitting

regimentation nor masters-of-the-universe narcissism is going to be a sustainable

model for organizing and managing talent in the new economy. The quest for a Goldilocks

‘just right’ integration of individual talent and collective productivity has a ways to go. If the

solution to this paradox were simple, socialism would have had a better record. There’s a

reason that athletic coaches who master the synergy of talent and teamwork wind up in a

Hall of Fame.

But businesses still need to engage human talent and still need to organize it somehow.

And the same rushing technological imperative that makes creative collaboration an ever

more urgent challenge for business success also offers new opportunities for realizing it.

The momentum of the emerging Collaboration Wave, whose signs are already tangible

now, seems destined only to grow over the next several years. We cannot predict the

future any more reliably than most stockbrokers. But there are some already visible trends

to suggest that significant change is coming in how information technology will relate to

how people work, and how people work with other people.

Tomorrow: the Relationship Paradigm

Much of what we see so far in the HCM solutions market aims simply to automate or

outsource rather inefficient, labor-intensive bureaucratic functions to reduce costs and

administrative overhead, and perhaps headcount. Not that there’s anything wrong with

that. (Apologies to Jerry Seinfeld.) But even if digital bureaucracy may be more efficient

and less costly, it’s still bureaucracy.

The growth opportunity: Relationship Capital Management

The real ‘value-added’ solutions will be not so much in human capital as in relationship

capital. Driven by the gathering Collaboration Wave, a growing number of IT companies

are now focused on the market for ‘xRM’—as in Relationship Management, where ‘x’ may

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 10 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

TRADEOFFS IN HCM PARADIGMS

Inventory management focuses on the content, turnover, and

allocation of the organization’s inventory of HC. Relationship

Inventory v. Relationship management focuses on creating productive relationships among

employees, suppliers, customers, and other people who participate in

the organization’s business.

Increasing the amount of people employed v. making more productive

Recruiting v. Productivity

use of the people who are employed.

Organizational intelligence has multiple sources: Individual ‘genius.’

Genius v. Teamwork v. System Intelligence High-performance teamwork. ‘Artificial’ intelligence embedded in

information systems.

Credentials are resumes, diplomas, transcripts, licenses, affiliations,

Credentials v. Competence and other proxies of ability. Competence is know-how and know-what

demonstrated in actual, relevant performance.

Practitioners as administrators of rules, regulations, and requirements

v. practitioners as consultants who help shape and improve the

Administrative Control v. Strategic

performance of the organization’s business. The analogy in

Consulting

instructional practice is “the sage on the stage” v. “the guide on the

side.”

Focus on the functions of particular ‘jobs’ v. the culture of the

Function v. Culture

organization.

Inventory approach centrally manages individual rewards, whether for

personal or group performance. Relationship approach allows self-

Incentives: ‘I’ v. ‘We’

directed teams to manage shared rewards. Tradeoff involves mixing

approaches to achieve some optimal synergy for the enterprise.

Viewing people as ‘resources’ to be ‘employed’ for the use of the

production process v. viewing people as members who join an

Employment v. Membership organization on the basis of shared mission and values.

be customer, supplier, partner, or other. In the networked economy, the ‘relationship web’

is where corporate valuation increasingly is spawned. Again, most of today’s HCM

solutions are not oriented to the xRM space.

As rich as the opportunities in xRM are likely to become, there is a caveat: We’ve seen

that the ‘business collaboration’ category currently is confused about what ‘collaboration’

really means. Too often it is identified simply with computer-to-computer interaction across

some process path, whether ‘supply chain’ or ‘sales chain’ or other. But ‘collaborating,’ like

knowing, is something people do.

Failing to grasp that distinction could prove an expensive mistake for customers and

vendors alike. The huge costs from ignoring human factors in the implementation of ERP

and other enterprise IT systems over the last decade now threaten to be repeated, even

magnified, in the pursuit of business collaboration. InternetWeek reports that the design of

today’s Customer Relationship Management applications, for example, does not

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 11 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

“complement the way sales people, customer service representatives and other front-line

employees do their jobs….” And for companies, the price of this failure is “an expensive

and time-consuming implementation that yields no return on investment.”

The space where the most acute needs and most potentially profitable IT opportunities are

now is neither in human capital management nor business collaboration management but

the amalgam of both: collaborative relationship management centered on human factors.

The instinct of HR professionals is correct when they try to reposition themselves as

‘performance consultants’—strategic management roles are attached to flows and

processes rather than stock or inventory. The central problem of managing corporate

performance is a matter of managing team or group performance, not individual

performance. But too many HCM IT ‘solutions’ focus on inventory management rather

than on organizational relationships and processes. This is similar to the trap that has

bogged down ‘Knowledge Management’ in shuffling document repositories rather than

energizing human collaboration. That’s not to say that these functions have no value or

demand. It’s just that they do not, alone, lead to the more ‘strategic’ role that HR, IT, and

other staff professionals desire.

Loyalty: relationships not containment

Something like lifetime (at least long-term) employment and valuing loyalty were more

common in business, especially in the U.S., a few decades ago than they have been

lately. In recent years, there has been greater enthusiasm for the flexibility of more

contingent, transitory employment. But the locus of that enthusiasm seems to shift with

changing circumstances. During the go-go economy of the past decade, in-demand

workers liked the upward mobility job-hopping seemed to offer, while employers’

appreciation for the virtues of loyalty and retention grew in step with the ferocity of the

bidding war for talent. Today, as the bears have chased the bulls away, the parties seem

to have switched philosophies: Beleaguered CEOs now abhor ‘fixed costs’ and savor the

flexibility of contingent employment. Meanwhile, new MBAs who a year or so ago chased

dreams of rapid wealth in start-up land now flock to the security of a Blue Chip corporate

cocoon.

As Japan and Europe learned, too much loyalty and too little turnover can be a real

economic handicap. On the other hand, it seems true that many U.S. companies

underestimate the costs of turnover, not only in added overhead and lost productivity, but

the possibly greater loss of experience and knowledge.

But as long as our framework is constrained to the inventory paradigm of employment, the

ambivalent cases for loyalty and retention versus mobility and turnover may remain

arbitrary and unresolvable. In the alternative, relationship paradigm, ‘loyalty’ or ‘retention’

does not mean just the preservation of the status quo in a working relationship. Rather, it

is more a matter of maintaining goodwill in business relationships as they evolve through

changing circumstances.

There are at least two practical reasons for this. One is the common-sense recognition, as

the saying goes, that ‘what goes around comes around.’ The relationships you may be

forced to cut loose today—whether with employees, suppliers, partners, customers or

others—may become important again in the future. When they do, you are clearly better

off if they are friendly than if they are hostile. Beyond common sense, this technically is an

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 12 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

application of ‘real options’ theory—there is a real present value of ‘purchasing’ an option

to make a choice sometime in the future, just as there is in the stock or commodities

markets.

The second practical reason for maintaining goodwill in working relationships is an

extension (and a correction) of Knowledge Management. It turns out in practice that

‘capturing’ and archiving ‘tacit knowledge’ is mostly impossible. As IBM resident expert

Laurence Prusak argues, knowing is mainly something that people do. And it is very hard

to know what people know or how they know what they know or how to verbalize any of

that—whether for yourself or for others. As Isadora Duncan is supposed to have said to a

reporter who asked her to explain the meaning of her dance, “If I could talk about it I

wouldn’t have to dance it.” Initial analysis following the recent completion of the human

genome map suggested that there may be far less information in human genes than was

widely expected. So the genes appear to be much less a ‘blueprint’ for building a human

being than a set of guidelines. The remaining information required to complete the

construction is contained in the context of the biochemical stew in which the genes get

expressed as proteins.

When a company severs relationships with employees and other people who know its

product and its business, it risks losing ‘intangible’ but valuable intellectual capital. So even

if financial or other exigencies require changing a current relationship, it pays to try to

preserve as much of the mental and emotional engagement as possible. And business

research bears this out. Research shows that companies that simplistically ‘downsize’

during a recession generally do not achieve greater competitiveness, profitability, or even

cost savings. Rather (as common sense would suggest), companies that shared

information openly with employees, provided early warning of necessary changes, and

made every effort to preserve employment before resorting to layoffs saved more money

in the short run and were more competitive and profitable in the longer run.

From STS design to Complexity: toward self-organization

The polymath Thomas Jefferson not only founded but also designed the architecture of

the University of Virginia. At the end of construction, the builders asked Jefferson, as the

final step, where they should pave walkways connecting the buildings. “Wait until the first

snow,” Jefferson famously advised: the students’ footprints would trace where the

walkways belonged.

This tale gives the flavor of what the pioneers of sociotechnical systems design were

reaching for half a century ago, which is being reinforced today by the lessons for

organizational design that business theorists are drawing from the modern mathematics of

complexity. Their basic insight is that self-organizing, self-adaptive complex systems, left

to their own devices, are able to generate effective solutions in the absence of any

centralized command from headquarters. Actually, they often are better able.

So the relationship paradigm not only overturns the Taylor-based, inventory vision of

‘human capital.’ Progressively it also is transforming the industrial meaning of

‘management’ as command-and-control, buy-and-sell, win-or-lose to something that is

both more ecological and more literally ‘ethical.’ Ecological in the sense of the corporation

as an ecosystem of living, interacting entities that may be ‘husbanded’ but not controlled.

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 13 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

Ethical in the sense of leading people by tending the combination of vision and values that

comprises the corporate ethos.

Personalizing teamwork

Many of today’s HCM solutions equate ‘personalization’ with simply offering ‘self-selection’

from a corporate-defined menu. But that is miles away from enabling the kind of

personalization, customization, and collaboration that is needed, says consultant Susanne

Kelly, co-author of The Complexity Advantage. As Kelly sees it, most companies have

been far readier to personalize and customize their relationships with customers than they

have with employees. Simplistically, we could say that e-CRM is far more advanced than

e-HRM in that regard.

In particular, data mining, collaborative filtering, and similar technologies are now used to

improve business understanding of what customers want, how they want it, and how they

value the products and services that the market offers them. Applying similar tools to

generate greater understanding of how and why people work together could greatly

improve not only personalization but productivity and the satisfaction of worklife.

Both the needs and opportunities for Personalization of working relationships are growing.

But the inventory paradigm, focusing on the individual employee in isolation, misses both

the need and the trend. Echoing Alvin Toffler’s prescient notion of ‘mass customization’ is

a similar virtuous paradox: personalized teamwork. That is not just a matter of

empowering each individual but empowering communities of individuals (teams, interest

groups, communities of practice) to ‘flock’ together through self-direction.

Hyperlearning: toward virtual experience

On a chart, the ‘learning curve’ looks like a flattened S-shaped, horizontal line. While

organizational psychologists realized soon after its discovery that the curve implied that

the workforce must have been learning from experience, there wasn’t much that

management could do to change the curve’s shape. The ‘learning’ in the curve was

welded to experience—defined strictly in terms of the cumulative volume of production.

Simply, the only way to learn more, faster, was to produce more, faster.

What managers could do with the learning curve was project costs more accurately for

setting prices or making bids on contracts. Significantly, they also could increase

productivity and hence profits by accelerating production volume—by trying to speed up

sales and to capture a greater market share. And, following the path of STS and other

organizational innovations aimed at empowering workers and enhancing teamwork, they

hoped to make it easier for the workforce to learn from experience and apply the learning

to ‘continuous improvement.’

But while these actions could sometimes make the slope of the learning/experience curve

steeper, they did not alter the basic equation and form of the curve. Through most of the

decades that followed the discovery of the learning curve in the 1930s, few if anyone

imagined that the learning process itself could be altered or managed.

The exploding power and growing integration of computing and telecommunication

technologies finally, in the last decade, created possibilities to transform the processes of

corporate learning, bending the old learning curve virtuously ‘out of shape.’ In place of the

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 14 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

old production-bound learning is an emerging ‘hyperlearning’ process. If charted, the

hyperlearning curve would look less like a line extending in lockstep with production and

more like a loop or spiral, wrapped around and practically independent of actual

production.

The most powerful driver of this hyperlearning transformation may be the growing

collaborative use of simulation and modeling by product development teams to design and

test new products such as the Boeing 777 in ‘virtual reality’ before, as the engineers say,

“the first piece of metal is bent.”

Similar (sometimes the same) simulation technology increasingly is applied to training,

testing, and recruiting of the workforce. Better knowledge management, performance

support, and e-learning systems are converging to concentrate more knowledge,

intelligence, and learning at the point where work is done. And neural networks and other

increasingly intelligent tools are not merely instruments of learning—they do learning.

Compensation quandary

As it commonly does in times of economic distress, ‘performance-based’ compensation

has become a popular topic in management circles lately. But ‘rewarding performance’ is

hardly a new or innovative idea. In the inventory paradigm, monitoring an individual’s work

and rewarding individual performance has been a common practice; the most elemental

form long has been identified with piecework sweatshops, migrant grape pickers, and

such. The inventory paradigm also has experience with rewarding individuals on the basis

of group performance, in the form of profit-sharing, stock options, and so forth.

The unresolved challenge of compensation strategy is finding the effective balance

between group incentives and individual incentives. What digital complexity now offers is

at least the possibility of allowing self-organizing social systems to optimize around both

without central, command planning.

Elusive business models

With the Collaboration Wave, the whole architecture of the Internet environment is moving

in a direction that parallels and supports the shift from the inventory paradigm toward the

relationship paradigm. Today’s telecomputing technology already is helping to accelerate

this business transformation. And the limits of the power and usability of technology are

bound to steadily recede.

From a market perspective, existing examples such as Napster, eBay, instant messaging,

online gaming, and others raise the possibility that at least some of the IT innovations that

are most effective at enabling new and powerful forms of social organization may offer no

profitable business model. Consumers of course welcome tools that are more or less free,

open, and standard. Profit-seeking vendors of relationship management ‘solutions,’ on the

other hand, in some cases will need to devise customized, value-added, proprietary

products that can be added on to the ‘free’ architecture. Or, vendors may need to shift

their business models to focus less on products and more on value-adding services.

The shift of organizational needs toward the relationship paradigm poses a further

dilemma for IT solution vendors. The vertically stovepiped structure of typical corporate

bureaucracies offers no directly relevant ‘port of entry’ for solutions that span the

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 15 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

boundaries of the organization chart—which is precisely what effective solutions to the

complex sociotechnical needs of the new economy organization should do.

So vendors of relationship solutions often will find it more difficult to target the right

customer for their marketing and sales. IT staff may not be sensitive to the human benefits

of relationship solutions, or may just view the organizational issues as beyond the IT

domain. But HR staff may not be prepared to evaluate sophisticated technology, or may

not be empowered to purchase an IT solution even if they appreciate it. And financial

controllers may be unenthusiastic about solutions that promise, or threaten, to decentralize

management control.

Conclusion

There is a strong, broadly shared sense that the terrorist attacks on the United States on

and after September 11, 2001 have changed the world in profound and enduring ways.

These events are still too recent at the time this is written to anticipate the sweep of their

social and economic impacts.

Still, it seems evident that the growing threats to security and survival only have raised the

stakes and increased the urgency of the Collaboration Wave charted above. The systems

of collaborative work and commerce that already had evolved prior to last September

immediately were challenged to adapt to the new threat environment. At the same time,

social-technical infrastructures for security, defense, and disaster management in the U.S.

and other modern societies were shown to have acute needs for enhanced intelligence,

agility, speed, and boundary-spanning collaboration.

In the wake of the attacks, the liabilities from the lack of collaboration across the various

pieces of the 'intelligence community' instantly became a more tangible and more urgent

problem. Similar lack of collaboration across and among the multiple agencies concerned

with law enforcement, immigration, public health, emergency management, and even

philanthropy have now become critical issues of national security.

While some, inevitably, have indulged in finger-pointing to assign ‘fault,’ the public mood

broadly has been far less one of blame than it is a powerful mandate to increase

collaboration across bureaucratic turf to close the gaps in security and crisis response.

The public sector is under pressure now to catch and surpass the Collaboration Wave that

already has surged in private industry. George Tenet, director of the U.S. Central

Intelligence Agency, for example, testified in Senate hearings that the CIA and other

organizations need to leverage the Internet and other technologies to “enhance

collaboration and the flow of information to move information faster than we ever have

before.” And Robert Wardell, special assistant to the chairman of the military Joint Chiefs

of Staff told a reporter that the Pentagon is seeking ways to enable soldiers on the ground

in such places as Afghanistan to “establish ad hoc computer connections with forces, say,

inside helicopters in Uzbekistan, or with officers back home and even with allies

abroad….”

The needed collaboration is not just across the public sector, but at least equally with and

among the private sector. Greater public/private collaboration now is being pushed where

it is both needed and productive, as in transportation. But security threats demand greater

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 16 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

private/private sector collaboration for two reasons: (1) Because security/crisis risks are

tangible to business now, and business will usually be better served by collaborating to

define its own solutions quickly, rather than waiting for government to impose them. (2)

Because, in fact, economic growth is the number one security issue for the U.S. and the

modern global economy in general.

Growth is needed, most broadly, because reversing and ultimately destroying the

development of the open society and the open global market economy is the prime goal of

our terrorist enemies—economic insecurity and decline is victory for terrorism.

Pragmatically, Fortune magazine estimates that enhanced security and resiliency needed

to protect the economic infrastructure has added some $150 billion per year of frictional

costs to the U.S. economy alone. So growth needs to be accelerated to offset these costs.

Last but hardly least, broader, more constructive and socially appealing globalization is

essential to win whole populations over to the side of modernity and away from the siren

call of terrorist violence and nihilism. And, greater, more secure, more productive

collaborative work and commerce are crucial driving forces for growth of the modern,

global economy.

XXX

Dr. Lewis J. Perelman is a management and policy consultant based in the Washington,

DC area.

Email: kanbrain@post.harvard.edu

Web: www.LinkedIn.com/in/LewisJPerelman

COLLABORATION WAVE PAGE 17 FEB 2002

© 2002 , 2011, LEWIS J. PERELMAN

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Value of Business Intelligence (New Management, 1983)Document6 pagesThe Value of Business Intelligence (New Management, 1983)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Kanban To Kanbrain (Forbes ASAP, 1994)Document7 pagesKanban To Kanbrain (Forbes ASAP, 1994)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Questionable Value of Best PracticesDocument2 pagesThe Questionable Value of Best PracticesLewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- How Hypermation Leaps The Learning Curve (Forbes ASAP, 1993)Document7 pagesHow Hypermation Leaps The Learning Curve (Forbes ASAP, 1993)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Our Lesson - Why School Is Out (The Futurist Mar-Apr 1986)Document4 pagesLearning Our Lesson - Why School Is Out (The Futurist Mar-Apr 1986)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Strategy Revolution (Strategic Planning Management, 1984)Document2 pagesThe Strategy Revolution (Strategic Planning Management, 1984)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Paradigm Revolution (Planning Review, 1983)Document2 pagesParadigm Revolution (Planning Review, 1983)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ark Plan - Solar Age (1980)Document1 pageThe Ark Plan - Solar Age (1980)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- THE HYPERCUBE: Organizing Intelligence in A Complex World (2001)Document6 pagesTHE HYPERCUBE: Organizing Intelligence in A Complex World (2001)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Near-Term Potential of Climate-Friendly TechnologiesDocument35 pagesNear-Term Potential of Climate-Friendly TechnologiesLewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The American Learning Enterprise in Transition (OECD 1989)Document96 pagesThe American Learning Enterprise in Transition (OECD 1989)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Parable of Scubation (1994)Document3 pagesThe Parable of Scubation (1994)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Learning Revolution (1993)Document11 pagesThe Learning Revolution (1993)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Near-Term Potential of Climate-Friendly TechnologiesDocument35 pagesNear-Term Potential of Climate-Friendly TechnologiesLewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- School's Out (WIRED 1.01, 1993)Document7 pagesSchool's Out (WIRED 1.01, 1993)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Time in System Dynamics (1980)Document15 pagesTime in System Dynamics (1980)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Closing Education's Technology Gap (Hudson Institute, 1989)Document12 pagesClosing Education's Technology Gap (Hudson Institute, 1989)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Capital Investment For State Economic Development (Western Governors Assoc., 1988)Document29 pagesHuman Capital Investment For State Economic Development (Western Governors Assoc., 1988)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- TECHNOS Interview of Lewis J. Perelman (Fall 1997)Document7 pagesTECHNOS Interview of Lewis J. Perelman (Fall 1997)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Opportunity Cost (WIRED, Nov 1996)Document4 pagesOpportunity Cost (WIRED, Nov 1996)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Barnstorming With Lewis PerelmanDocument7 pagesBarnstorming With Lewis PerelmanLewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Learning EnterpriseDocument78 pagesThe Learning EnterpriseLewis J. Perelman100% (1)

- The Virtual UniversityDocument5 pagesThe Virtual UniversityLewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Speculations On The Transition To Sustainable Energy (1980)Document25 pagesSpeculations On The Transition To Sustainable Energy (1980)Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Shifting Security Paradigms - Toward ResilienceDocument26 pagesShifting Security Paradigms - Toward ResilienceLewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Brazil May Become The Saudi Arabia of Ethanol. or The Iraq.Document5 pagesBrazil May Become The Saudi Arabia of Ethanol. or The Iraq.Lewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Infrastructure Risk and Renewal: The Clash of Blue and Green - PERI Symposium ProceedingsDocument103 pagesInfrastructure Risk and Renewal: The Clash of Blue and Green - PERI Symposium ProceedingsLewis J. Perelman100% (1)

- Carbon Policy: The Right - and Wrong - Ways To Use NAFTADocument14 pagesCarbon Policy: The Right - and Wrong - Ways To Use NAFTALewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Homeland Security Is Always Political, So Deal With ItDocument2 pagesHomeland Security Is Always Political, So Deal With ItLewis J. PerelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Crisis of Infrastructure Resilience: The Clash of Blue, Green, and RedDocument12 pagesThe Crisis of Infrastructure Resilience: The Clash of Blue, Green, and RedLewis J. Perelman100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Syllabus African ArtDocument5 pagesSyllabus African ArtjuguerrPas encore d'évaluation

- Moral Relativism Explained PDFDocument14 pagesMoral Relativism Explained PDFJulián A. RamírezPas encore d'évaluation

- An Ethic of Care CritiqueDocument4 pagesAn Ethic of Care CritiqueJoni PurayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rethinking Diaspora(s) : Stateless Power in The Transnational MomentDocument35 pagesRethinking Diaspora(s) : Stateless Power in The Transnational MomentCoca Lolo100% (1)

- Czech Republic Communication TableDocument4 pagesCzech Republic Communication Tableapi-270353850Pas encore d'évaluation

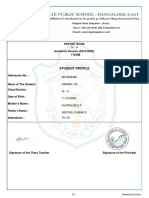

- Student Profile: Report BookDocument3 pagesStudent Profile: Report BookchitradevipPas encore d'évaluation

- On Open Letter To The White ManDocument50 pagesOn Open Letter To The White ManTravis Hall0% (2)

- Letter of Application CAEDocument8 pagesLetter of Application CAEAleksandra Spasic100% (1)

- How We Express Ourselves 1 17 13Document4 pagesHow We Express Ourselves 1 17 13api-147600993100% (1)

- UCSP - Understanding Culture Society and Politics: More Superior Than OthersDocument2 pagesUCSP - Understanding Culture Society and Politics: More Superior Than OthersRyle Valencia Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- 129Document7 pages129TuanyPas encore d'évaluation

- Hall, Stuart. Local and Global.Document12 pagesHall, Stuart. Local and Global.PauloMaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2013) - Developing L2 Pragmatics PDFDocument19 pagesBardovi-Harlig, K. (2013) - Developing L2 Pragmatics PDFjpcg1979100% (1)

- Tips - The Warrant Chiefs Indirect Rule in Southeastern N PDFDocument350 pagesTips - The Warrant Chiefs Indirect Rule in Southeastern N PDFISAAC CHUKSPas encore d'évaluation

- Analytical ExpositionDocument12 pagesAnalytical Expositionmarkonah56Pas encore d'évaluation

- Freedom Jesus Culture Chord Chart PreviewDocument3 pagesFreedom Jesus Culture Chord Chart PreviewAndy CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- ApostropheDocument1 pageApostropheOmar H. AlmahdawiPas encore d'évaluation

- Participative Management and Employee and Stakeholder Ok, Chapter of BookDocument22 pagesParticipative Management and Employee and Stakeholder Ok, Chapter of BookflowersrlovelyPas encore d'évaluation

- Protsahan BrochureDocument6 pagesProtsahan BrochuresharadharjaiPas encore d'évaluation

- My Notes - Human Rights LawDocument2 pagesMy Notes - Human Rights LawMary LeandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fragmented Citizenships in GurgaonDocument11 pagesFragmented Citizenships in GurgaonAnonymous GlsbG2OZ8nPas encore d'évaluation

- Travel Writing - Legal IssuesDocument7 pagesTravel Writing - Legal Issuesaviator1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Business Issues SyllabusDocument6 pagesContemporary Business Issues Syllabusgeenius8515Pas encore d'évaluation

- Child Care 2 - Connection Between Reading and WritingDocument12 pagesChild Care 2 - Connection Between Reading and Writingrushie23Pas encore d'évaluation

- Internship ReportDocument32 pagesInternship ReportMinawPas encore d'évaluation

- Disappearance of MayansDocument4 pagesDisappearance of MayansBwallace12Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bravery Stands Tall Washington Crossing The DelawareDocument8 pagesBravery Stands Tall Washington Crossing The Delawareapi-273730735Pas encore d'évaluation

- E Tech DLL Week 7Document3 pagesE Tech DLL Week 7Sherwin Santos100% (1)

- The Rise of Nationalism in EuropeDocument15 pagesThe Rise of Nationalism in EuropeG Abhi SheethiPas encore d'évaluation

- Diglossia and Early Spelling in Malay (24 Pages)Document24 pagesDiglossia and Early Spelling in Malay (24 Pages)Nureen SyauqeenPas encore d'évaluation