Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Opinion of The Court: Holder V Humanitarian Law Project

Transféré par

Andrew Hill0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

64 vues9 pagesThis Opinion of the Court is a product of my senior year constitutional law course: Current Cases before the Supreme Court. Before my professor and two classmates - acting as Supreme Court Justices - I argued for Holder and the United States government. The assignment that followed was this opinion: I wrote for the Court majority.

Titre original

Opinion of the Court: Holder v Humanitarian Law Project

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThis Opinion of the Court is a product of my senior year constitutional law course: Current Cases before the Supreme Court. Before my professor and two classmates - acting as Supreme Court Justices - I argued for Holder and the United States government. The assignment that followed was this opinion: I wrote for the Court majority.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

64 vues9 pagesOpinion of The Court: Holder V Humanitarian Law Project

Transféré par

Andrew HillThis Opinion of the Court is a product of my senior year constitutional law course: Current Cases before the Supreme Court. Before my professor and two classmates - acting as Supreme Court Justices - I argued for Holder and the United States government. The assignment that followed was this opinion: I wrote for the Court majority.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 9

1!

Opinion of the Court

Notice: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the

preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to

notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States,

Washington, D.C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, which

Justice Hill is particularly prone to making, in order to make corrections

made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

ERIC H. HOLDER, JR., ATTORNEY GENERAL, ET AL.,

v.

HUMANITARIAN LAW PROJECT, ET AL.

[December 14, 2009]

JUSTICE HILL delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case concerns the Antiterrorism and Effective

Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) of 1996, which grants the

Secretary of State discretion to designate foreign terrorist

organizations as such. Both the Kurdistan Workers Party

(PKK) and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)

were designated so the year AEDPA passed. U.S.C.

2339B(a)(1) of AEDPA makes illegal the provision of

material-support to designated foreign terrorist

organizations. Material-support, as defined by 18 U.S.C.

2339A(b)(1), includes:

any property, tangible or intangible, or service, in-

cluding currency or monetary instruments or finan-

cial securities, financial services, lodging, training,

expert advice or assistance, safehouses, false docu-

mentation or identification, communications equip-

merit, facilities, weapons, lethal substances, explo-

sives, personnel (1 or more individuals who may be

or include onself), and transportation, except medi-

cine or religious materials. (Emphasis added)

2!

Opinion of the Court

Humanitarian Law Project, et al., prior to AEDPA’s

passage, provided material-support to what it contends are

non-violent, law-abiding wings of said organizations.

Respondents brought their case(s), post-passage, premised

on the contention that material-support, as defined, is

unconstitutionally vague, to District Court, seeking an

injunction.

The United States District Court ordered a preliminary

injunction barring the enforcement of U.S.C. 2339B(a)(1),

citing the terms “training” and “personnel,” both of which

comprise material-support, as unconstitutionally vague.

The Government appealed the order to the Court of Appeals,

and that court affirmed. A second action was brought

against the Government, on grounds that the term “expert

advice or assistance,” also located in U.S.S. 2339B(a)(1), is

unconstitutionally vague. It too came before the Court of

Appeals.

During both sets of appeals, Congress passed the

Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act (IRTPA)

of 2004. This Act clarified the definitions of two terms in

question. “Training” no longer relied on its general

definition, instead becoming statutorily defined: "instruction

or teaching designed to impart a specific skill, as opposed to

general knowledge." 18 U.S.C. 2339A(b)(2). “Expert advice

or assistance,” too, became clarified: “advice or assistance

derived from scientific, technical, or other specialized

knowledge.” 18 U.S.C. 2339A(b)(3). In light of clarification,

both Courts of Appeals remanded the cases to the lower

courts.

Both cases, post-remand, were consolidated before the

District Court, where Respondents claimed the terms

“training,” “personnel,” “expert advice or assistance,” and

3!

Opinion of the Court

“service” are unconstitutionally vague. The District Court

agreed, save the term “personnel,” and the United States

Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed, ordering an

injunction, declaring the terms in question

unconstitutionally vague. We grant the Government’s

petition for certiorari and vacate the judgment of the Court

of Appeals.

We think the Court of Appeals erred in its decision.

The Court of Appeals’ holding rests on an erroneous

contention: that the terms in question are vague. These

terms include “training,” “expert advice and assistance,” and

“service.” Not one of these terms is vague, the general1 and

statutory2 definitions of each are clear. A person of ordinary

intelligence would be able to understand the meaning of

each, satisfying the Fifth Amendment Due Process

requirement. The vagueness doctrine is, in other words,

inapplicable.

The IRTPA defined the term “training” to include only

“instruction or teaching designed to impart a specific skill,

as opposed to general knowledge.” 18 U.S.C. 2339A(b)(2).

This definition, so claims the Court of Appeals, is vague

because it requires individuals to draw impossible

distinctions between prohibited instruction in a “specific

skill” and permissible instruction in “general knowledge.”

Respondents are forced to guess whether human rights

advocacy, a form of training, is a “specific skill” or relies on

“general knowledge.” The fact is, Respondents (like the

average person) are able to distinguish between common

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

1 Webster’s Third New International Dictionary defines each term in question with certain lucidity.

Terms defined in this publication are what we shall refer to as “general definitions.”

2 The IRTPA clarifies the meaning of each word. Terms defined within this Act are what we shall

refer to as “statutory definition.”!

4!

Opinion of the Court

knowledge and knowledge that is so specialized that it is

foreign to the experiences of most people.

Respondents introduce a hypothetical: Under the

Government’s definition, teaching geography would be

permissible because it constitutes “general knowledge,” but

teaching the political geography of terrorist organizations

would constitute a banned “specific skill,” as would the

teaching of English. Such a focused transfer of information

might be construed as imparting a “specific skill.” How is

the layman to know the difference? This argument is duly

noted, but holds little merit. Persons of ordinary

intelligence can distinguish between what is commonly or

generally known and what is a skill possessed by relative

few. Whether or not vague in hypothetical situations,

Respondents’ conduct falls under the definition of training

in both the statutory and general definition. Whether said

term is vague in other contexts is irrelevant.

More broadly, respondents’ arguments indicate only

that under this statute, as under any statute, "imagination

can conjure up hypothetical cases" in which there is

uncertainty. American Commc’ns Ass’n v. Douds, 339 U.S.

382, 412 (1950). Respondents fail to show that the statute

does not give a person of ordinary intelligence a reasonable

opportunity to know what is prohibited." Grayned v. City of

Rockford, 408 U.S. 104, 108 (1972).

The term “expert advice or assistance” fulfills the 5th

Amendment Due Process requirement that a person of

ordinary intelligence be able to understand the term’s

meaning. The Court of Appeals held that “expert advice or

assistance”, clarified by the IRTPA as “imparting scientific,

technical, or other specialized knowledge” is vague and that

“scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge” fails to

clarify the term “expert advice or assistance.” The Court of

5!

Opinion of the Court

Appeals concluded that while “scientific” and “technical”

knowledge is lucid, “other specialized knowledge” is not. To

argue that point, under the principle of ejusdem generis,

“other specialized knowledge” takes its meaning from the

surrounding terms “scientific” and “technical.”

A person with no legal background, contends the Court

of Appeals, would find the term in question unintelligible.

Moreover, all general knowledge, contends the Court of

Appeals, was once specialized knowledge and this in some

sense is derived from such knowledge. In rebuttal,

Petitioner contends (and this Court agrees) that the statute

applies to advice derived from what is currently specialized

knowledge – not to what is now general knowledge but was

once specialized knowledge at some point in the past.

The Court of Appeals held that “service” is vague

because each of the other challenged provisions could be

construed as a provision of service. The term service, says

the Court of Appeals, presumably includes providing

members of the PKK and LTTE with “expert advice or

assistance” on how to lobby or petition representative bodies

such as the United Nations. “Service” would also include

training members of the PKK or LTTE on how to use

humanitarian and international law to resolve ongoing

disputes. “Service” is clear in any related capacity, as

determined by 387 F3d 144 United Sates v. Homa

International Trading Corporation, it was determined that

the term “service,” as used in a statute prohibiting the

export of “services” to Iran, is “unambiguous.” This term

may be understood by a person of ordinary intelligence and,

like the two previous terms, is not unconstitutionally vague.

6!

Opinion of the Court

II

This Court holds the vagueness doctrine inapplicable to

the terms (and statute) in question. “Training,” “expert

advice or assistance,” and “service” may be understood by a

person of ordinary intelligence, satisfying the 5th

Amendment Due Process requirement. By looking to the

plain words that compose the statutory and general

definitions, there is no denying the modest, if not crystal,

clarity of each term. The foundation of this Court’s rejection

of Respondent’s contention is in concert with that of

Petitioner. Petitioner contends that the Court of Appeals

conflated the vagueness and overbreadth doctrines; that a

statute’s broad application demonstrates breadth, not

vagueness. In suggesting that “training,” “expert advice and

assistance,” and “service” are vague because each might be

construed to prohibit First Amendment freedoms, the Court

of Appeals reveals its fundamentally flawed (though

perhaps forgivable) thinking. It has applied the overbreadth

doctrine, but termed it the vagueness doctrine.

According to the overbreadth doctrine, a statute that

affects First Amendment rights is unconstitutional if it

prohibits more protected speech than is necessary to achieve

an important government interest.

According to the vagueness doctrine, a crime defined so

vague that a person of ordinary intelligence could not

determine what elements constitute the crime, qualifies it as

such. Such a vague statute is unconstitutional on the basis

that a defendant could not defend himself or herself against

a charge of a crime, which he or she could not understand,

and thus would be denied due process required by the 5th

Amendment.

7!

Opinion of the Court

If a statute is overbroad, it restricts protected rights,

where a statute deemed vague is simply unintelligible. The

two are clearly distinct.

As we determined, none of the three terms in question

is vague. The statutory and general definition of each may

be understood by a person of ordinary intelligence. The

terms in question may, however, be overbroad. The Court of

Appeals held that any of the three terms could be construed

to prohibit First Amendment freedoms. For instance, the

Court of Appeals reasoned training is vague because it could

be read to encompass speech and advocacy protected by the

First Amendment. This brings us to the second question

that demands judgment. Are the terms in question

overbroad? The Court of Appeals, in its holding, declared

the statute as just broad enough. Petitioner, however,

contends the contrary. We find it necessary to address this

claim, insofar as to buttress our central holding.

Respondents contend the statute in question is

overbroad because it regulates speech. We do not consider

this so. The statute in question regulates conduct,

specifically the provision of material-support to designated

foreign terrorist organizations. Speech is regulated only

incidentally. Given this fact, we subject this statute to

intermediate scrutiny under the four-pronged test set out in

United States v. O’Brian.

The O’Brian test requires: 1) that the regulation be

within the government’s power; 2) that the regulation

promote an important interest; 3) that the interest be

unrelated to restricting free expression; and 4) that the

regulation restrict First Amendment rights no more than

necessary. U.S.C 2339B(a)(1) satisfies each requirement. 1)

The regulation is within the government’s power, it is the

8!

Opinion of the Court

federal government’s prerogative to regulate the dealings of

its citizens with foreign entities; 2) the regulate does

promote an important interest, specifically the prevention of

global terrorism; 3) the interest is unrelated to restricting

free expression, it is related to stopping terrorism; and 4)

the regulation restricts First Amendment rights no more

than necessary, it is narrowly tailored given the deference

due Congress in foreign affairs.

The regulation in question satisfies the O’Brian test.

This in mind, we assert that the terms in question are just

broad enough, not overbroad (and certainly not vague).

III

Not as weighty as each aforementioned contention, but

important nonetheless, are several pertinent facts. These

facts weigh on our decision. Firstly, the political branches

(i.e. Congress and the President) are due deference in

foreign affairs. Both branches are aware of the dangers that

threaten the United States of America that the Supreme

Court of the United States, and all lower courts, are not.

The CIA, wise to the threat of foreign terrorist organizations,

does not debrief the courts, but does debrief Congress. This

in mind, it is best to grant latitude to the Government.

Secondly, there is a strong case to be made that support

given to the PKK and LTTE, material or other, funds

terrorist activities. Respondents maintain that they support

only the non-violent, law-abiding wings of these

organizations. After all, Respondents aim to help these

groups seek assistance from the United Nations, the

outcome of which may reduce violence. Still, support, and

the money to which that support is tantamount, is fungible.

If Respondents provide a service free of charge, then money

is freed up in other, perhaps violent, law-breaking wings.

9!

Opinion of the Court

There exists little oversight in these organizations, so one

cannot, in all certainty, know where money flows. For all

Respondents may be aware, the services they contribute to

said organizations may help free up cash to pay for terrorist

activities that put at risk American lives.

We weight heavily the fact that no term in question,

“training,” “expert advice and assistance,” or “service,” is

vague. We also weight heavily the fact that no term in

question is overbroad. According to the O’Brian test, the

statute in question is legitimate, appropriate, and

constitutional. It is also in our mind that the political

branches are due deference and that service to those

designated terrorist organizations, to which money is

tantamount, is fungible. All of this in mind, we come to our

decision. We remand and reverse the ruling of the Ninth

Circuit Court of Appeals.

It is so ordered.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Odpowiedzialność Cywilna Z Tytułu Wad ProduktuDocument19 pagesOdpowiedzialność Cywilna Z Tytułu Wad ProduktuKatarzyna Strębska-LiszewskaPas encore d'évaluation

- Matter 2Document33 pagesMatter 2Cetacean HumpbackPas encore d'évaluation

- Cook v. State of RI, 10 F.3d 17, 1st Cir. (1993)Document14 pagesCook v. State of RI, 10 F.3d 17, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- The One Made by The Declarant While Testifying at A Trial orDocument8 pagesThe One Made by The Declarant While Testifying at A Trial orAdi CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- US V Purganan (MR)Document6 pagesUS V Purganan (MR)NN DDLPas encore d'évaluation

- James Harvey Johnson v. Warden Noah Alldredge and Corrections Officer Cronrath, 488 F.2d 820, 3rd Cir. (1973)Document10 pagesJames Harvey Johnson v. Warden Noah Alldredge and Corrections Officer Cronrath, 488 F.2d 820, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Descriptive Questions With Answers: 1. To Which Proceedings Is The Indian Evidence Act Applicable?Document47 pagesDescriptive Questions With Answers: 1. To Which Proceedings Is The Indian Evidence Act Applicable?Alisha VaswaniPas encore d'évaluation

- CASE NO. 13-4429 United States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitDocument21 pagesCASE NO. 13-4429 United States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitEquality Case FilesPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court Material Support OpinionDocument65 pagesSupreme Court Material Support OpinionThe Dallas Morning NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Harvard Westlake Engel Neg Alta Round4Document15 pagesHarvard Westlake Engel Neg Alta Round4Fabio JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Joe Pepe, 501 F.2d 1142, 10th Cir. (1974)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Joe Pepe, 501 F.2d 1142, 10th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Doctrine of Estoppel Under The Indian Evidence ActDocument18 pagesDoctrine of Estoppel Under The Indian Evidence ActSushant NainPas encore d'évaluation

- Ui - Administrative Law II Lecture NotesDocument78 pagesUi - Administrative Law II Lecture NotesAdeyemi adedolapoPas encore d'évaluation

- Brownell v. Tom We Shung, 352 U.S. 180 (1956)Document5 pagesBrownell v. Tom We Shung, 352 U.S. 180 (1956)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence ProjectDocument18 pagesEvidence ProjectAayush SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Galeza, Dorota Hard CasesDocument27 pagesGaleza, Dorota Hard CasesAndreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Abhaydev-20191bal9001-Evidence Law Research Paper-1Document22 pagesAbhaydev-20191bal9001-Evidence Law Research Paper-1Satyam ThakurPas encore d'évaluation

- Drafting Pleading and Conveyancing Project O: Injunctions and Its Kinds'Document18 pagesDrafting Pleading and Conveyancing Project O: Injunctions and Its Kinds'Shubhankar ThakurPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Law - SynthèseDocument190 pagesCommon Law - SynthèseNate AGPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavits by Peter Hanauer, Ll.b.Document55 pagesAffidavits by Peter Hanauer, Ll.b.Julian Williams©™100% (1)

- Civil CasesDocument5 pagesCivil CasesSIDFlux TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- Peruta v. California Thomas DissentDocument8 pagesPeruta v. California Thomas DissentWashington Free BeaconPas encore d'évaluation

- Jay Artz v. Jo Anne B. Barnhart, Commissioner of The Social Security Administration, 330 F.3d 170, 3rd Cir. (2003)Document8 pagesJay Artz v. Jo Anne B. Barnhart, Commissioner of The Social Security Administration, 330 F.3d 170, 3rd Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Law 2 OutlineDocument15 pagesConstitutional Law 2 OutlinepasmoPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Law 1 NotesDocument92 pagesEvidence Law 1 NotesAkello Winnie princesPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Law Review Crammer'S Guide (Finals)Document20 pagesPolitical Law Review Crammer'S Guide (Finals)Ar-Reb AquinoPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. John Doe, 980 F.2d 876, 3rd Cir. (1992)Document12 pagesUnited States v. John Doe, 980 F.2d 876, 3rd Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Law 2 OutlineDocument16 pagesConstitutional Law 2 Outlinepasmo100% (1)

- Bryan Kohberger: Order Denying Motion To Dismiss IndictmentDocument13 pagesBryan Kohberger: Order Denying Motion To Dismiss IndictmentLeigh EganPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Batuklal 1Document48 pagesEvidence Batuklal 1Enkay67% (9)

- Stilted Standards of Standing PDFDocument38 pagesStilted Standards of Standing PDFSam MaulanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Insanity OverviewDocument23 pagesInsanity OverviewMissy MeyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Assignment Law 035 Introduction To Legal Learning SkillsDocument12 pagesFinal Assignment Law 035 Introduction To Legal Learning SkillsManaf MahmudPas encore d'évaluation

- Writ of Amparo Ppt2Document19 pagesWrit of Amparo Ppt2Anonymous 1lYUUy5TPas encore d'évaluation

- Minneci v. Pollard, 132 S. Ct. 617 (2012)Document18 pagesMinneci v. Pollard, 132 S. Ct. 617 (2012)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- In The United States District Court For The District of ColumbiaDocument12 pagesIn The United States District Court For The District of ColumbiaChrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Evidence Notes MLTDocument15 pagesLaw of Evidence Notes MLTKomba JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Calvin Hardee v. Robert Kuhlman, Acting Superintendent, Woodbourne Correctional Facility, 581 F.2d 330, 2d Cir. (1978)Document8 pagesCalvin Hardee v. Robert Kuhlman, Acting Superintendent, Woodbourne Correctional Facility, 581 F.2d 330, 2d Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Evidence Assignment Semester 06 LLB 3year 01Document21 pagesLaw of Evidence Assignment Semester 06 LLB 3year 01Mayur KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- The "Ambiguity" Fallacy: Ryan D. DoerflerDocument11 pagesThe "Ambiguity" Fallacy: Ryan D. DoerflerĐăng KhoaPas encore d'évaluation

- NYULawReview 83 1 Portnoi 試用情況Document30 pagesNYULawReview 83 1 Portnoi 試用情況howen520Pas encore d'évaluation

- Adr Assignment PDFDocument16 pagesAdr Assignment PDFraj rastogiPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept of Natural JusticeDocument28 pagesConcept of Natural JusticeMaruf Allam80% (5)

- Chapter One: Evidence Law General IntroductionDocument207 pagesChapter One: Evidence Law General IntroductionsitotawPas encore d'évaluation

- Lex Lata Ed 1 of 2014Document6 pagesLex Lata Ed 1 of 2014Tawanda ZhuwararaPas encore d'évaluation

- Crtiorary N ProhibitionDocument6 pagesCrtiorary N ProhibitionAgustino BatistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hoult v. Hoult, 57 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1995)Document12 pagesHoult v. Hoult, 57 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- JR HazardousWastesKnowing 1990Document16 pagesJR HazardousWastesKnowing 1990preston brownPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotation On Offer of Evidence (Legal Research)Document19 pagesAnnotation On Offer of Evidence (Legal Research)noorlawPas encore d'évaluation

- Anthony Andrews v. United States, 441 F.3d 220, 4th Cir. (2006)Document14 pagesAnthony Andrews v. United States, 441 F.3d 220, 4th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Chaos in The Courtroom Reconsidered Emotional Bias and Juror NullificationDocument20 pagesChaos in The Courtroom Reconsidered Emotional Bias and Juror NullificationJen ShawPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court DecisionDocument3 pagesSupreme Court DecisionKJPas encore d'évaluation

- IntroductionDocument3 pagesIntroductionxfv2fkvpdbPas encore d'évaluation

- NSDS EVIDENCE101 A PRIMERONEVIDENCELAW 03jun141Document14 pagesNSDS EVIDENCE101 A PRIMERONEVIDENCELAW 03jun141wensislaus chimbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Project On EstoppelDocument22 pagesEvidence Project On EstoppelPrerna Delu0% (1)

- Rubie Rogers, and Cross-Appellants v. Robert Okin, M.D., and Cross-Appellees, 634 F.2d 650, 1st Cir. (1980)Document18 pagesRubie Rogers, and Cross-Appellants v. Robert Okin, M.D., and Cross-Appellees, 634 F.2d 650, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Writ of AmparoDocument34 pagesWrit of AmparoKim Escosia100% (1)

- SA U14 Wills and Succession June 2011 PDFDocument14 pagesSA U14 Wills and Succession June 2011 PDFNathan NakibingePas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals For The Second CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Second CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide Civil AppealsDocument159 pagesGuide Civil AppealswircexdjPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 43 - Appeals FRM CTA & QJADocument3 pagesRule 43 - Appeals FRM CTA & QJAJoseph PamaongPas encore d'évaluation

- Con Law Fed State FlowchartDocument5 pagesCon Law Fed State Flowchartrdt854100% (1)

- Sanidad V Comelec GDocument3 pagesSanidad V Comelec GEugene DayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Moncayo Integrated Small-Scale Mining Association vs. South East Mindanao Gold Mining CorporationDocument2 pagesMoncayo Integrated Small-Scale Mining Association vs. South East Mindanao Gold Mining CorporationJug HeadPas encore d'évaluation

- LTD - Director of Lands Vs IAC GR No. L-73002Document4 pagesLTD - Director of Lands Vs IAC GR No. L-73002Maya Sin-ot ApaliasPas encore d'évaluation

- Tan v. CincoDocument9 pagesTan v. CincoPrincess Trisha Joy UyPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurisdiction of Civil CourtsDocument19 pagesJurisdiction of Civil CourtsHarjyot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Shabnam and Saleem Press Release - 25 May - 25.5.15 @1615Document1 pageShabnam and Saleem Press Release - 25 May - 25.5.15 @1615Live LawPas encore d'évaluation

- Defamation and Contempt of CourtDocument4 pagesDefamation and Contempt of CourtHarsh DixitPas encore d'évaluation

- Sabah State ConstitutionDocument45 pagesSabah State ConstitutionR,RyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of ConstitutionDocument4 pagesDefinition of ConstitutionVishnu PathakPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative Law Work 1Document9 pagesAdministrative Law Work 1bagumaPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory Regarding Plaint and Written Statement-Obaid Khan 1887036Document6 pagesTheory Regarding Plaint and Written Statement-Obaid Khan 1887036supervuPas encore d'évaluation

- Complaint On Senior Kansas Judge John Sanders - Kansas Commission On Judicial Qualifications December 30, 2019 - Kasey KingDocument13 pagesComplaint On Senior Kansas Judge John Sanders - Kansas Commission On Judicial Qualifications December 30, 2019 - Kasey KingConflict GatePas encore d'évaluation

- 1611RDocument30 pages1611RRaushan Tara JaswalPas encore d'évaluation

- International Shoe v. State of Washington - 326 U.S. 310 (1945) - Justia US Supreme Court CenterDocument16 pagesInternational Shoe v. State of Washington - 326 U.S. 310 (1945) - Justia US Supreme Court CenterDeanna Clarisse HecetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bale ImgDocument2 pagesBale ImgsectionbcoePas encore d'évaluation

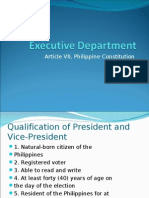

- Article VII, Philippine ConstitutionDocument47 pagesArticle VII, Philippine ConstitutionDiaz Ragu100% (4)

- CBEA vs. BSPDocument4 pagesCBEA vs. BSPblue_blue_blue_blue_bluePas encore d'évaluation

- Del Castillo, J.:: Factual AntecedentsDocument5 pagesDel Castillo, J.:: Factual AntecedentsShine MerillesPas encore d'évaluation

- Dinesh Kumar Bhardwaj Vs State Bank of India Thru' Regional ... On 20 November, 2015Document17 pagesDinesh Kumar Bhardwaj Vs State Bank of India Thru' Regional ... On 20 November, 2015Bijay TiwariPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Procedures NotesDocument12 pagesCriminal Procedures NotesKingPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 CasesDocument11 pages1 Casesnaim indahiPas encore d'évaluation

- Burger King Corp. v. RudzewiczDocument2 pagesBurger King Corp. v. RudzewiczSam Mate100% (1)

- Portea Vs PabellonDocument2 pagesPortea Vs PabellonIvan Montealegre ConchasPas encore d'évaluation

- Nottebohm Case DigestDocument2 pagesNottebohm Case DigestJazztine Artizuela100% (3)

- Philippine Banking Corporation v. TensuanDocument3 pagesPhilippine Banking Corporation v. TensuanJoshua Buenaobra CapispisanPas encore d'évaluation

- Paddy Land Circular Setaside Judgment 403694Document36 pagesPaddy Land Circular Setaside Judgment 403694sdevanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lacson v. Executive SecretaryDocument3 pagesLacson v. Executive SecretaryMatt LedesmaPas encore d'évaluation