Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

086 - Personal Values and Mall Shopping Behavior - The Mediating Role of Attitudes of Chinese and Thai Consumers

Transféré par

Sidharth RayDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

086 - Personal Values and Mall Shopping Behavior - The Mediating Role of Attitudes of Chinese and Thai Consumers

Transféré par

Sidharth RayDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Page 1 of 10

ANZMAC 2010

Personal Values and Mall Shopping Behavior: The Mediating Role of Attitudes of Chinese and Thai Consumers

Yuanfeng Cai, College of Management, Mahidol University, bonniecyf@yahoo.com.cn Randall Shannon, College of Management, Mahidol University, a.randall@gmail.com

Abstract In this study, a value-attitude-behavior and a value-attitude-intention-behavior hierarchical model were tested in Thailand and China, respectively, to understand how consumers mall shopping behavior could be influenced by their personal values orientation in a non-Western context. The results revealed that while a valueattitude-behavior model could be used to profile Thai shoppers, a value-attitudeintention-behavior model worked better to portray Chinese shoppers. The findings imply that the mediating effect of shopping intention in these models may vary upon consumers shopping motives. Key words: personal values, attitudes, intention, mall shopping behavior.

Page 2 of 10

ANZMAC 2010 Personal Values and Mall Shopping Behavior: The Mediating Role of Attitudes of Chinese and Thai Consumers Introduction Over the decades, the notion developed that personal values can serve as grounds for behavioral decisions in consumption behavior (Carman, 1977; Williams, 1979; Kropp, Lavack and Holden, 1999; Doran, 2009). Consumption behaviors are viewed as a means to achieving desired end states or values, which has been well documented in the literature (Gutman, 1982; Reynolds and Gutman, 1988; Michon and Chebat, 2004). However, the major criticism of examining a simple relationship between values and behavior is that values are relatively abstract, thus are viewed as distal determinants of behavior that can only affect behavior through a number of less abstract or more proximal determinants, like attitudes and beliefs (e.g., Rokeach, 1968; Vinson, Scott and Lamont, 1977; Stern & Oskamp, 1987; Horton and Horton, 1990; Homer & Kahle, 1988; McCartly and Shrum, 1993, 1994; Grunert and Juhl, 1995; Thogersen and Grunert, 1997; Shim and Eastlick, 1998; Jayawardhenas, 2004). Accordingly, a value-attitude-behavior (VAB) hierarchy was developed and has been validated in healthy food consumption (Homer and Kahle, 1988; Grunert and Juhl, 1995), environmental behavior (McCartly and Shrum, 1993; Thogersen and Grunert, 1997), and more recently, e-shopping behavior (Jayawardhena, 2004). The testing of the model in a mall setting is relatively new and has been limited. In their seminal study, Shim and Eastlick (1998) replicated Homer and Kahles (1988) study, and found that compared with the previous study, the link between attitude and behavior was weaker in a mall setting, which implies the existence of additional factors that may influence this relationship. Shim and Eastlicks (1998) study was based in a Western context, thus it is unclear whether similar findings will hold in a non-Western context and whether the findings will differ across nations. The lack of studies in this domain has triggered our interest to bridge the gaps by testing the value-attitude-behavior model across two non-Western nations (i.e., China and Thailand) and explore additional mediators to gain further insight into the valuebehavior link. Literature Review & Hypotheses In the previous study, it was found that although attitude toward a shopping mall can directly influence mall shopping behavior, correlation between these two constructs was relatively weak (Shim and Eastlick, 1998). One possible reason may be attributed to the omission of the intention. A number of theorists have argued that compared with attitude, the intention to perform a behavior, is a closer cognitive antecedent of actual behavioral performance (eg., Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Fisher & Fisher, 1992; Gollwitzer, 1993). Intentions have been found to be predicted accurately by attitudes (Shepherd et al., 1988), and the more favorable the attitude with respect to a behavior, the stronger is the individuals intention to perform the behavior under consideration (Ajzen, 1991). Additionally, the effect of intentions in the attitude-behavior relation has been found

Page 3 of 10

varied along the level of effort needed to perform the behavior (Bagozzi and Yi, 1989; Bagozzi et al., 1990; Schultz and Oskamp, 1996). According to Bagozzi et al., (1990), behaviors that require much effort are mostly determined deliberately and result from conscious thought processes before forming behavioral intentions; likewise, behaviors that require little effort are guided by less deliberate thoughts directly stimulated by attitudes. When the behavior requires substantial effort, the mediating role of intentions will be strong, and attitudes will have only indirect effects on behavior; when the behavior requires little effort, attitudes will influence behavior directly and the mediating role of intentions will be reduced. A review of the literature suggests that Chinese mall shoppers are more likely to be utilitarian driven (Tse et al., 1989; Tse, 1996; Li et al., 2004). Utilitarian shoppers tend to view shopping as work or a burden rather than fun (Rao and Monroe 1989; Sherry 1990; Nicholls et al. 2000), and they are more time conscious than recreational shoppers (Hansen & Deutscher 1977/78; Bellenger and Korgaonkar, 1980; Wilson and Holman 1984). Thus, it is assumed that deliberate conscious evaluation concerning the mall visit will be required for them to make the visit decision. Consequently, the intention to shop will be more likely to form as the end result of the evaluation of the behavior. Thus: H1: In the Chinese sample, the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy is mediated by shopping intention. Phillips (1966) proposed mai pen rai and sanuk, as two important Thai values. The value of mai pen rai (literally, something doesnt matter) suggests that adverse outcomes will get better eventually, so one should not worry about them, while the value of sanuk (literally, fun and joy) reflects that Thais tend to view life as full of fun and joy and not to be taken too seriously, even in the context of work (Warner, 2003). In addition, influenced by Buddhist teachings, Thais exhibit a strong present orientation. Several scholars have noted their tendency to seek present or immediate gratification (Skinner, 1962; Slagter and Kerbo, 2000). Chetthamrongchai and Davies (2000) proposed that hedonic shoppers score relatively high on present orientation, indicating that they are more concerned with what is happening now than in the past or in the future. Taken together, it is suggested that Thai shoppers will be more likely to shop for hedonic reasons. Hedonic shoppers tend to view shopping as fun rather than burden, thus less effort will be required for making the mall visit decision. Therefore: H2: In the Thai sample, the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy is not mediated by shopping intention. Research Methodology A self-administered survey was used to collect the data in both countries. The survey questionnaire was developed based upon a comprehensive review of related literature, as well as the result of a focus group with five respondents in China. Twenty-two items were selected from the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) (Schwartz, 1992) to measure personal values. Respondents were asked to rate each item on a 9-point unipolar scale with the end points not important at all and of decisive importance as a guiding principle in my life. The respondents were instructed to read the list of

Page 4 of 10

values first, then list out the value that was most important to them, and then list out the value most opposed to their values. They were then to rate the remaining values based on their importance. Based on the literature review (Bellenger et al., 1977; Wong et al., 2001; Sit et al., 2003) and the result of the focus group, twenty-two mall attributes were selected to measure respondents attitudes toward shopping malls. By employing convenience sampling, the total number of usable returned questionnaires was 643, with 320 in China, and 323 in Thailand, with a response rate of 30-40% in each country. Fewer usable surveys were obtained in China because many respondents did not understand what a shopping mall is, confusing it with other shopping venues such as department store, great merchandiser or anchor supermarket within a shopping mall, likely because the format is relatively new. After the data editing and cleaning up processes, the final number of questionnaires with no missing values for all variables under analysis was 305 in China, and 308 in Thailand. In terms of overall demographics, 90% were aged between 20 to 38, 69% were female, 71.6% were single and 82.7% had no children, 57.4% had a bachelors degree 65.7% were white collar, and 45.1% had monthly income between 2000 to 6000 Yuan (or 10,000 to 30,000 Baht). Compared with Chinese respondents, Thai respondents were older, better educated and more affluent (p=.000). Results of Analysis Before running the measurement model, a principal component factor analysis using varimax rotation was first conducted to identify underlying dimensions of values (Homer and Kahle, 1988; Shim and Eastlick, 1998). This was due to three reasons: 1) the importance of personal value dimensions tend to be varied upon situational factors in different contexts (Kahle, 1983; Beatty et al., 1991; Homer and Kahle, 1988); 2) it is suggested that resultant factors should be used in a causal modeling technique (Kahle and Kennedy, 1989); 3) to avoid the single-item measurement that is frequently raised in value surveys (Braithwaite and Scott, 1991). Measurement Model Results In the present study, SPSS 16.0 and structural equation modeling via AMOS 17.0 were used to test the hypotheses in both countries. Before proceeding with structural equation modeling (SEM), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed initially to validate the scales measuring the constructs (Hair et al., 2006). The results of the measurement model in both samples indicate that the factor loadings of the latent variables were generally high and statistically significant (i.e., >.50). The fact that all t-tests were significant indicated that all items were measuring the construct they were associated with. In addition, convergent validity may be further evidenced if each indicators standardized loading on its posited latent construct is greater than twice its standard error (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). The results indicate that all items under investigation met this requirement. Discriminant validity is demonstrated if both AVEs are greater than the squared correlation, and were met by both samples. Note that shopping behavior was a single item scale in the model, therefore, it was adjusted to reflect estimated variance. Using the level of reliability (.85) employed

Page 5 of 10

in previous studies (Joreskog and Sorbom, 1993; Shim and Eastlick, 1998), the error variance for the scale was estimated at .15 (1- reliability) (Hair et al., 2006, p.857). In the present study, shopping behavior was measured by money spent during the mall visit. Structural Equation Model Results In the Chinese sample, the value-attitude-behavior model was tested initially. The result indicated that the model demonstrated an acceptable fit with the data (2 =430.052, df=185, p=.000, GFI=.88, CFI=.85, RMSEA=.066). As hypothesized, personal values were positively correlated with attitudes (value1= .54, p<.001, value2= .19, p= .006), and attitudes were positively correlated with behavior (attitude =.18, p=.021). The results confirm the existence of value-attitude-behavior hierarchy in Chinese context. The value-attitude-intention-behavior model was then tested to justify the hypothesis. Its final model yielded a 2 value of 546.196 (p=.000), with 247 degree of freedom, GFI of .87, CFI of .85, RMSEA of .063 demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data. As hypothesized, attitudes were positively correlated with shopping intention (= .49, p<.001), and shopping intention was positively associated with shopping behavior (= .20, p=.010). The mediating effect of shopping intention was further confirmed with Baron and Kennys (1986) procedure. Therefore, H1 was supported. Similarly, the value-attitude-behavior model was tested first with the Thai sample, the model yielded a 2 value of 423.916 (p=.000) with 246 degree of freedom, and a GFI of .89, CFI of .89, RMSEA of .049, which demonstrated an acceptable fit with the data. The significant path coefficients also confirmed the existence of value-attitudebehavior hierarchy in a Thai context (value= .15, p =.044; attitude = .21, p=.036). In the test of value-attitude-intention-behavior model, although the statistics revealed that the model demonstrated an acceptable fit with the data (2 =554.582, p=.000, df=317, GFI=.88, CFI=.88, RMSEA=.049), a significant coefficient was not found for shopping intention. The result revealed that attitudes had a positive influence on shopping intention (attitude = .38, p<.001), but shopping intention did not correlate with behavior. In this regard, it can be concluded that shopping intention does not mediate the attitude-behavior link in the Thai sample. Therefore, H2 was supported. Discussion and Conclusions First, the results of this study provide empirical evidence to verify the existence of a value-attitude-behavior hierarchy in a non-western mall context. That is, personal values only influence mall shopping behavior indirectly through the mediating effect of attitude (Shim and Eastlick, 1998). In addition to attitudes, the results of this study suggested that shopping intention served as an additional factor that can be used to better explain the value-behavior relationship. Nevertheless, it was found that the value-attitude-intention-behavior model can only be used to understand shopping behavior of Chinese consumers, while the value-attitude-behavior model works better to predict Thai shoppers behavior. One possible reason behind is that shopping intention tends to emerge in the attitude-behavior link when level of effort needed to perform the behavior is high (Bagozzi and Yi, 1989; Bagozzi et al., 1990; Schultz and Oskamp, 1996). Arguably, the level of effort needed for mall shopping may vary upon the shopping motives. That is, consumers who shop for utilitarian reasons will

Page 6 of 10

need a relatively higher level of effort to conduct the shopping behavior. In contrast, consumers who shop for hedonic reasons will need a relatively lower level of effort to make the shopping decision. Although not directly tested, this study may shed some light for researchers about how value-behavior relationships will be influenced when consumers have different shopping motives. The testing of the value-attitudebehavior hierarchy based on different shopping motives may provide an interesting direction for future research.

Page 7 of 10

References: Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50, 179-211. Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W., 1988. Structural Equation Modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Pshchological Bulletin 103, 411-23. Bagozzi, R. and Yi, Y.J., 1989. The degree of intention formation as a moderator of the attitude-behavior relationship. Social Psychology Quarterly 52(4), 266-79. Bagozzi, R.P., Yi, Y. and Baumgartner, J., 1990. The level of effort required for behavior as a moderator of the attitude-behavior relation. European Journal of Social Psychology 20, 45-59. Beatty, S.E., Kahle, L.R. and Homer, P., 1991. Personal values and gift-giving behaviors: a study across culture. Journal of Business Research 22, 149-157. Bellenger, D.N., Robertson, D.H and Greenberg, B.A., 1977. Shopping center patronage motives. Journal of Retailing 53, 29-38. Bellenger, D.N. & Korgaonkar, P.K., 1980. Profiling the recreational shopper. Journal of Retailing 56(3), 77-92. Braithwaite, V.A. and Scott, W.A., 1991. Values. 661-753 in John P. Robinson, Phillip R. Shaver, and Lawrence S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes, Academic Press, Inc. Carman, J.M., 1977. Values and consumption patterns: a closed loop. 403-07 in H.K. Hunt (Ed.). Advances in Consumer Research 5. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research. Chetthamrongchai, P. and Davies, G., 2000. Segmenting the market for food shoppers using attitudes to shopping and to time. British Food Journal 102 (2), 81-101. Doran C.J., 2009. The role of personal values in fair trade consumption. Jouranl of Business Ethics 84, 549-63. Fishbein, M., & I. Ajzen, 1975. Belife, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Fishbein, M. & M.J. Manfredo, 1992. A theory of behavior change. In influencing human behavior: theory and applications in recreation, tourism, and natural resource management, ed. M.J. Manfredo, 29-50. Champaign, IL: Sagamore. Gagnon, J.L., and Chu, J.J., 2005. Retail in 2010: a world of extremes. Strategy & Leadership 33(5), 13-23. Gollwitzer, P.M., 1993. Goal achievement: the role of intentions. In W.Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European Review of Social Psychology 4, 141-85. Chichester, UK:

Page 8 of 10

Wiley. Grunert, S. & Juhl, H., 1995. Values, environmental attitudes, and buying of organic foods. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39-62. Gutman, Jonathan, 1982. A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes. Journal of Marketing 46, 60-72. Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., and Tatham, R., 2006. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Hansen, R. and T. Deutscher, 1977/78. An empirical investigation of attribute importance in retail store selection. Journal of Retailing 53(4), (Winter), 59-64. Homer,P.M. & Kahle, L.R., 1988. A structural equation test of the value-attitudebehavior hierarchy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54, 638-46. Horton, R.L., & Horton, P.J., 1990. Organ donation and values: identifying potential organ donors. In Proceedings of the Society for Consumer Psychology, Meryl P. Gardner, ed., Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 55-59. Jayawardhena, Chanaka, 2004. Personal values influence on e-shopping attitude and behavior. Internet Research 14(2), 127-38. Joreskog, K.G. and Sorbom. D., 1993. LISREL 8. Chicago, IL:Scientific Software International, Inc. Kahle, Lynn R., 1983. Social Values and Social Change: Adaptation to Life in America, New York: Praeger. Kahle, L.R., and Kennedy, P., 1989. Using the List of Values (LOV) to understand consumers. The Journal of Consumer Marketing 6, 5-11. Kropp, F., Lavack, A.M. and Holden, S.J.S., 1999. Smokers and beer drinkers: values and consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of Consumer Marketing 16(6), 536-57. Li, Fuan; Zhou, Nan; Nicholls, J.A.F; Zhuang, Gujun; Kranendonk, Carl, 2004. Interlinear or inscription? A comparative study of Chinese and American mall shoppers behavior. The Journal of Consumer Marketing 21(1), 51. McCarty, J.A and Shrum, L.J., 1993. The role of personal values and demographics in predicting television viewing behavior: implications for theory and application. Journal of Advertising 22(4), 77-101. McCarty, J.A and Shrum, L.J., 1994. The recycling of solid-wastes: personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. Journal of Business Research 30(1), 53-62. Michon, R. and Chebat, J.C., 2004. Cross-cultural mall shopping values and habits: a

Page 9 of 10

comparison between English and French-speaking Canadians. Journal of Business Research 57(8), 883. Nicholls, J.A.F., Li, F., Mandokovic, T., Roslow, S. & Kranendonk, C.J., 2000. USChilean mirrors: shoppers in two countries. Journal of Consumer Marketing 17(2), 106-119. Phillips, H., 1966. The Thai Peasant Personality, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Rao, Akshay R. and Kent B. Monroe, 1989. The effect of price, brand name and store name on buyers perceptions of product quality: an integrative review. Journal of Marketing Research 26 (August), 351-357. Reynolds, Thomas J. and Jonathan Gutman, 1988. Laddering theory, method, analysis, and interpretation. Journal of Advertising Research 28, 11-34. Rokeach, M., 1968. Belife, Attitudes, and Values: A Theory of Organization and Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Schwartz, S.H., 1992. Universals in the structure and content of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries, in Zanna, M.P. (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25, Academic Press, Orlando, FL, 1-65. Schultz, P.W. and Oskamp, S., 1996. Effort as a moderator of the attitude-behavior relationship: general environmental concern and recycling. Social Psychology Quarterly 59(4), 375-83. Sheppard, B. H., Hartwick, J., & Warshaw, P.R, 1988. The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. Journal of Consumer Research 15, 325-343. Sherry, John F. Jr., 1990. A Socio-Cultural analysis of a midwestern flea market. Journal of Consumer Research 17 (June), 13-30. Shim. S., & Eastlick, M.A., 1998. The hierarchical influence of personal values on mall shopping attitude and behavior. Journal of Retailing 74(1), 139-60. Sit, J., Merrilees, B. and Birch, D., 2003. Entertainment-seeking shopping center patrons: the missing segments. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 31(2), 80-94. Skinner, W. G., 1962. Chinese Society in Thailand: An Analytical History. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Slagter, R. & Kerbo, H., 2000. Modern Thailand: A Volume in the Comparative Societies Series. New York: McGraw-Hill. Stern, P.C. & Oskamp, S., 1987. Managing scarce environmental resources. In D.

Page 10 of 10

Stokols & I. Altman (Eds. ), Handbook of Environmental Psychology, (1043-1088). New York: Wiley. Thogersen, J and Grunert, S.C., 1997. Values and attitudes formation towards emerging attitude objects: from recyclying to general, waste minimizing behavior. Advances in Consumer Research 24, 182-89. Tse, D.K., 1996. Understanding Chinese people as consumers: past findings and future propositions. In M.H. Bond (Ed.), Handbook of Chinese Psychology, 352-63. Tse, D.K., Belk, R.W., & Zhou N., 1989. Becoming a consumer society: a longitudinal and cross-cultural content analysis of prints ads from Hong Kong, the Peoples Republic of China, and Taiwan. Journal of Consumer Research 15 (March), 457-72. Vinson, D., Scott, J. & Lamont, L., 1977. The role of personal values in marketing and consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing April, 44-50. Warner, Malcolm, 2003. Culture and Management in Asia. New York: Routledge Curzon. Williams, R.M., Jr., 1979. Change and stability in values and value systems: a sociological perspective. In M. Rokeach (Ed.), Understanding Human Values: Individual and Societal. New York: Free Press. Wilson, R.D. and R.H. Holman, 1984. Time allocation dimensions of shopping Behavior. Academy of Consumer Research 11(1), 29-34. Wong G.K.M., Lu, Y., Yuan, L.L., 2001. SCATTR: an instrument for measuring shopping center attractiveness. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 29(2), 76-86.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- WCST ManualDocument234 pagesWCST ManualLaura González Carrión89% (47)

- Light Retention Scale, 5th Edition (LRS-5)Document1 pageLight Retention Scale, 5th Edition (LRS-5)Danielle PerjatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Group No 8 - Blue Tokai Coffee (Final Report)Document50 pagesGroup No 8 - Blue Tokai Coffee (Final Report)Sumit Bhagat100% (1)

- Measures of Personality and Social Psychological ConstructsD'EverandMeasures of Personality and Social Psychological ConstructsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Personal Values and Mall Shopping BehaviourDocument29 pagesPersonal Values and Mall Shopping BehaviourPutri AzharikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cross Cultural DifferencesDocument32 pagesCross Cultural DifferencesKwan KaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vietnamese Individual Investors' Behavior in The Stock Market: An Exploratory StudyDocument9 pagesVietnamese Individual Investors' Behavior in The Stock Market: An Exploratory StudyDang Doan NuoiPas encore d'évaluation

- w-3 CASE STUDY 3 STORE ENVIRONMENT AND CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR PDFDocument18 pagesw-3 CASE STUDY 3 STORE ENVIRONMENT AND CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR PDFSerena AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Cross-Cul Tural Dif Fer Ences in Con Sumer de Ci Sion-Mak Ing StylesDocument31 pagesCross-Cul Tural Dif Fer Ences in Con Sumer de Ci Sion-Mak Ing Stylesann2020Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparative Analysis of Consumer Behavior of Three CohortsDocument20 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Consumer Behavior of Three CohortsJezzyl DeocarizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender - Differences Intention To Buy Fair TradeDocument45 pagesGender - Differences Intention To Buy Fair TradeBharath WarajPas encore d'évaluation

- Repurchase Intention of Brand Automobile - TPBDocument11 pagesRepurchase Intention of Brand Automobile - TPBNguyen Manh QuyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Predicting Consumer Patronage Behaviour in The Egyptian Fast Food BusinessDocument17 pagesPredicting Consumer Patronage Behaviour in The Egyptian Fast Food BusinessSud HaPas encore d'évaluation

- Migration and BusinessDocument19 pagesMigration and BusinessPrachi Jain AggarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Cues-Customer Behavior Relationship: The Mediating Role of Emotions and CognitionDocument12 pagesSocial Cues-Customer Behavior Relationship: The Mediating Role of Emotions and CognitionhendraPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document9 pagesChapter 3Emmanuel MwapePas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurial Intention Among Chinese StudentsDocument11 pagesEntrepreneurial Intention Among Chinese StudentsMutiara WahyuniPas encore d'évaluation

- CheckDocument7 pagesCheckMehdi HassanzadePas encore d'évaluation

- An Empirical Investigation of The Relationships Among A Consumer's Personal Values, Ethical Ideology and Ethical BeliefsDocument19 pagesAn Empirical Investigation of The Relationships Among A Consumer's Personal Values, Ethical Ideology and Ethical BeliefsMomina AbbasiPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Store Atmospherics On Customer BehaviorDocument22 pagesImpact of Store Atmospherics On Customer BehaviorYunus KarakasPas encore d'évaluation

- An Analysis of Consumer Values, Needs and Behavior For Liquid Milk in Hazara, Pakistan (Saf)Document15 pagesAn Analysis of Consumer Values, Needs and Behavior For Liquid Milk in Hazara, Pakistan (Saf)Rao DaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment # 2 - Literature Review of Behavioral IntentionDocument14 pagesAssignment # 2 - Literature Review of Behavioral Intentionapi-3719928100% (1)

- Peran Keluarga Dalam Perilaku Pembelian Hedonis Sigit WibawantoDocument14 pagesPeran Keluarga Dalam Perilaku Pembelian Hedonis Sigit WibawantoMaya damayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Review LitDocument9 pagesReview LitBablu JamdarPas encore d'évaluation

- Tourism Management: Young Hoon Kim, Mincheol Kim, Ben K. GohDocument7 pagesTourism Management: Young Hoon Kim, Mincheol Kim, Ben K. GohLilyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Behaviour in Organizations: A Literature Review: Marmat Geeta, Jain Pooja, Mishra PNDocument6 pagesEthical Behaviour in Organizations: A Literature Review: Marmat Geeta, Jain Pooja, Mishra PNsaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory of Reasoned ActionDocument8 pagesTheory of Reasoned ActionraulrajsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- ShoppingOrientationandStoreImage PDFDocument10 pagesShoppingOrientationandStoreImage PDFDaeng SikkiPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review: Project TitleDocument16 pagesLiterature Review: Project TitleSiyuan HuPas encore d'évaluation

- Customer Style InventoryDocument9 pagesCustomer Style InventoryPRATICK RANJAN GAYEN50% (2)

- PR 1-2-3 (Questionnaire)Document18 pagesPR 1-2-3 (Questionnaire)allysa kaye tancioPas encore d'évaluation

- 06 Chapter 2Document32 pages06 Chapter 2hardikbhuva2804Pas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer PerceptionDocument14 pagesConsumer PerceptionBablu JamdarPas encore d'évaluation

- CB Final Project AnalysisDocument21 pagesCB Final Project AnalysisAprajita SaxenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Nature of Store Ambiance and Individual Impulse Buying Tendency On Impulsive Purchasing Behaviour: An Emerging Market PerspectiveDocument15 pagesUnderstanding Nature of Store Ambiance and Individual Impulse Buying Tendency On Impulsive Purchasing Behaviour: An Emerging Market PerspectiveJessica TedjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Male Skincare Buyer BehaviourDocument14 pagesMale Skincare Buyer BehaviourMuhammad AlJavaPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Norms Consumer BehaviourDocument5 pagesSocial Norms Consumer Behaviourteodora popescuPas encore d'évaluation

- 26 Tinashe ChuchuDocument14 pages26 Tinashe ChuchuSanchithya AriyawanshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: The Theory of Reasoned Action 1: Marketing Consumer BehaviorDocument9 pagesRunning Head: The Theory of Reasoned Action 1: Marketing Consumer BehaviorKirkfranck KipPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument10 pagesReview of Related LiteratureRuby AtasinPas encore d'évaluation

- Applying The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) in Saving Behaviour of Pomak HouseholdsDocument12 pagesApplying The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) in Saving Behaviour of Pomak HouseholdsTrix CCPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On Impulse BuyingDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Impulse Buyingeaibyfvkg100% (1)

- Han2012 Repurchase PDFDocument12 pagesHan2012 Repurchase PDFFAJAR SENTOSO ,Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1.literature Review: Impulse BuyingDocument4 pages1.literature Review: Impulse Buyingtender headPas encore d'évaluation

- Rajaguru RajeshDocument8 pagesRajaguru RajeshAtul PrasharPas encore d'évaluation

- Persuasion in The Marketplace How Theori PDFDocument36 pagesPersuasion in The Marketplace How Theori PDFDea JagoketikPas encore d'évaluation

- Mohan G., Sivakumaran B., Sharma P.Document22 pagesMohan G., Sivakumaran B., Sharma P.Νικόλας ΜερμίγκηςPas encore d'évaluation

- Nudging Progress To Date and Future DirectionsDocument17 pagesNudging Progress To Date and Future DirectionsRita ParushkinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment GuidelineDocument10 pagesAssignment GuidelineJefree SarkerPas encore d'évaluation

- 527 1348 1 PBDocument18 pages527 1348 1 PBGustu Pramana PutraPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On The Shopping Behavior of Duty Free Shop UsersDocument12 pagesA Study On The Shopping Behavior of Duty Free Shop Usersk60.2113340007Pas encore d'évaluation

- Zeithaml 1988Document21 pagesZeithaml 1988Rushi VyasPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0148296315003409 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0148296315003409 MainlucianaeuPas encore d'évaluation

- Attitudes and The Attitude-Behavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic ProcessesDocument34 pagesAttitudes and The Attitude-Behavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic ProcessesRocioCollahuaTorresPas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief Literature Review On Consumer Buying BehaviourDocument6 pagesA Brief Literature Review On Consumer Buying BehaviourShubhangi Ghadge75% (4)

- Impact of Cultural Values and Life Style On Impulse Buying Behavior: A Case Study of PakistanDocument8 pagesImpact of Cultural Values and Life Style On Impulse Buying Behavior: A Case Study of PakistanBerjees ShaikhPas encore d'évaluation

- Branding Iterature ReviewDocument21 pagesBranding Iterature ReviewMr PlagiarismPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Behaviour and Impulsive Buying BehaviourDocument38 pagesConsumer Behaviour and Impulsive Buying BehaviourNeeraj Purohit100% (3)

- The Influence of Personality Types On The Impulsive Buying Behavior of A ConsumerDocument9 pagesThe Influence of Personality Types On The Impulsive Buying Behavior of A ConsumerSilky GaurPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualitative Research:: Intelligence for College StudentsD'EverandQualitative Research:: Intelligence for College StudentsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Choosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesD'EverandChoosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing Social Policy: Multiple Perspectives for Critically Understanding and Evaluating PolicyD'EverandAnalyzing Social Policy: Multiple Perspectives for Critically Understanding and Evaluating PolicyPas encore d'évaluation

- Brand Activation: Do Something Awesome With PeopleDocument36 pagesBrand Activation: Do Something Awesome With PeopleSidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Statistical Tools For Data AnalysisDocument26 pagesStatistical Tools For Data AnalysisSidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On " Effectiveness of Brand Strategy of Britannia Biscuits "Document68 pagesA Study On " Effectiveness of Brand Strategy of Britannia Biscuits "joelcrasta83% (12)

- Science and Scientific RESEARCH-An IntroductionDocument27 pagesScience and Scientific RESEARCH-An IntroductionSidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- 3359 - Scale of Measurement, Reliabilty&ValidityDocument19 pages3359 - Scale of Measurement, Reliabilty&ValiditySidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

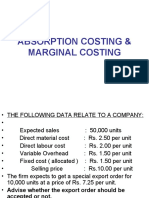

- Accounting For Decision Making (Adm) : Course Instructor: S.K.Padhi Class - 1Document23 pagesAccounting For Decision Making (Adm) : Course Instructor: S.K.Padhi Class - 1Sidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- MaterialsDocument5 pagesMaterialsSidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Absorption Vs MarginalDocument9 pagesAbsorption Vs MarginalSidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Cost Volume Profit AnalysisDocument20 pagesCost Volume Profit AnalysisSidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Cost SheetDocument2 pagesCost SheetSidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Cost ConceptsDocument21 pagesCost ConceptsAltaf AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- 4853 - CID-sessions 3-4-5Document35 pages4853 - CID-sessions 3-4-5Sidharth Ray100% (1)

- 4852 - CID - Sessions 1-2-3Document25 pages4852 - CID - Sessions 1-2-3Sidharth RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment and Certification of X Ray Image Interpretation Competency of Aviation Security ScreenersDocument31 pagesAssessment and Certification of X Ray Image Interpretation Competency of Aviation Security ScreenersJPFJPas encore d'évaluation

- #4 The Impact of Organizational Culture On Corporate PerformanceDocument10 pages#4 The Impact of Organizational Culture On Corporate PerformanceNaol FramPas encore d'évaluation

- Douglas Mcgregor'S Theory X and Y: Toward A Construct-Valid MeasureDocument17 pagesDouglas Mcgregor'S Theory X and Y: Toward A Construct-Valid MeasureSARIPAH ABDUL HAMIDPas encore d'évaluation

- HVV Articles-Topic 7Document16 pagesHVV Articles-Topic 7Diem HoangPas encore d'évaluation

- American Nurses Association Nursing Journal Toolkit-Quantitative Research Study Critique Guide To Research CritiqueDocument12 pagesAmerican Nurses Association Nursing Journal Toolkit-Quantitative Research Study Critique Guide To Research CritiqueAndreah YoungPas encore d'évaluation

- The Scale For Interpersonal Behaviour and The Wolpe-Lazarus Assertiveness Scale: A Correlational Comparison in A Non-Clinical SampleDocument5 pagesThe Scale For Interpersonal Behaviour and The Wolpe-Lazarus Assertiveness Scale: A Correlational Comparison in A Non-Clinical SampleSarah GracyntiaPas encore d'évaluation

- MAth Thesis 10gDocument29 pagesMAth Thesis 10gHag LakíuPas encore d'évaluation

- Inspiring Future Entrepreneurs: The Effect of Experiential Learning On The Entrepreneurial Intention at Higher EducationDocument12 pagesInspiring Future Entrepreneurs: The Effect of Experiential Learning On The Entrepreneurial Intention at Higher EducationIJELS Research JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- 20 Item Shyness ScaleDocument2 pages20 Item Shyness ScaleAzn_JennPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Differences in Abstract Reasoning: Psy101 Lab Report-02Document24 pagesGender Differences in Abstract Reasoning: Psy101 Lab Report-02Sabrina Tasnim Esha 1721098Pas encore d'évaluation

- Group Work ReportDocument33 pagesGroup Work ReportAiman LombokyPas encore d'évaluation

- Trends in Mathematics and Science StudyDocument16 pagesTrends in Mathematics and Science StudyWilliam Molnar100% (1)

- Most Essential Learning Competencies (MELC) - Based Modules Learners' Mastery and Performance in Mathematics VIDocument13 pagesMost Essential Learning Competencies (MELC) - Based Modules Learners' Mastery and Performance in Mathematics VIPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Rater ReliabilityDocument23 pagesRater ReliabilityNina SudimacPas encore d'évaluation

- Designing and Evaluating A Humanfactors Investigation Tool (HFIT) For Accident AnalysisDocument25 pagesDesigning and Evaluating A Humanfactors Investigation Tool (HFIT) For Accident AnalysisRauf HuseynovPas encore d'évaluation

- Measuring Young Children's Attitudes Toward Peers With Disabilities: Highlights From The ResearchDocument11 pagesMeasuring Young Children's Attitudes Toward Peers With Disabilities: Highlights From The Researchanggie mosqueraPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing A Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge TPACK Assessment For Preservice Teachers Learning To Teach English As A Foreign LanguageDocument17 pagesDeveloping A Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge TPACK Assessment For Preservice Teachers Learning To Teach English As A Foreign LanguageJoseph100% (1)

- Tuckman 2005Document7 pagesTuckman 20052021Arla Patra VarlinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Aljohns ReviewerDocument4 pagesAljohns Revieweraljohn_riveraPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 Foundations of SelectionDocument12 pages11 Foundations of SelectionMoaz JavaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Principles of Language Assessment - Practicality, Reliability, Validity, Authenticity, and WashbackDocument5 pagesPrinciples of Language Assessment - Practicality, Reliability, Validity, Authenticity, and Washbackscott tiger100% (1)

- Slide Workshop SmartPLS v2Document30 pagesSlide Workshop SmartPLS v2Delta100% (2)

- The Impact of Social Media Marketing On CustomerDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Social Media Marketing On CustomerNajamPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Social Influences PDFDocument21 pagesThe Role of Social Influences PDFRini SartiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Measuring Service Quality in Higher Education: Hedperf Versus ServperfDocument17 pagesMeasuring Service Quality in Higher Education: Hedperf Versus ServperfSultan PasollePas encore d'évaluation

- Item Analysis: Complex TopicDocument8 pagesItem Analysis: Complex TopicKiran Thokchom100% (2)

- Effectiveness of Geogebra in Learning Linear FunctionsDocument6 pagesEffectiveness of Geogebra in Learning Linear FunctionsChristian Elim SoliganPas encore d'évaluation