Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Dealing With Downstream Customers: An Exploratory Study

Transféré par

wubealemDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dealing With Downstream Customers: An Exploratory Study

Transféré par

wubealemDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study

Bas Hillebrand

Institute for Management Research, Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and

Wim G. Biemans

University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Abstract Purpose In B2B markets, the demand for a suppliers products is derived from demand further down the supply chain. This complexity poses several challenges for B2B rms, especially when they are located near the beginning of a supply chain. This study aims to investigate to what extent rms near the beginning of the supply chain are oriented towards downstream customers, the problems they encounter in extending their market orientation to include downstream customers, and how they deal with these problems. Design/methodology/approach This study uses an exploratory research method. It is based on in-depth interviews with 31 managers from 21 upstream suppliers. Findings The ndings suggest that rms are aware of the importance of downstream customers, but frequently fail to establish effective relationships with them. The paper identies several barriers that hamper an orientation on downstream customers and shows how rms may deal with these barriers. Research limitations/implications The paper includes several implications for further research, including the suggestion to test a set of seven propositions. Practical implications This study identies several barriers that may prevent a rm from implementing a downstream customer orientation as well as several strategies to deal with these barriers. Originality/value The paper explores the neglected implications of derived demand, one of the most distinctive characteristics of B2B marketing. Keywords Market orientation, Demand, Product development, Business-to-business marketing, Channel relationships Paper type Research paper

An executive summary for managers and executive readers can be found at the end of this article.

Introduction

Probably the most distinctive characteristic of rms supplying products to other rms, especially those positioned near the beginning of the supply chain, is that the demand for their products is derived from the demand for the customers products and thus, ultimately, end user demand (Fern and Brown, 1984). But surprisingly, the extant literature all but ignores the problems caused by derived demand. Most business-to-business (B2B) marketing textbooks dene derived demand, explain how it complicates demand forecasting, and argue that business marketers should look at both their immediate customers and the downstream markets served by them. But they fail to go beyond these general observations and offer insight into the consequences of derived demand, the managerial challenges it causes and solutions to deal with them. Similarly, the market orientation literature shows that market-oriented organizations are better

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0885-8624.htm

able to fulll customer demands and needs with superior products (Atuahene-Gima, 1995; Han et al., 1998; Li and Calantone, 1998), but popular conceptualizations of the market orientation construct only include immediate customers and neglect downstream customers (i.e. the customers customers, their customers etc). The neglect of these issues in the extant literature is in sharp contrast to the problems many B2B rms experience in dealing with downstream customers. For example, a focus on immediate customers only may harm both product and rm performance. After all, even though immediate customers may be interested in a product, success frequently requires downstream customers to also acknowledge the products value and invest in it. This is especially relevant for B2B suppliers of entering goods that become part of the customers product. Extending ones view beyond the rms immediate customers thus will contribute to product success and rm performance. This is in line with the original conceptualization of the market orientation construct (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990; Narver and Slater, 1990). As Narver and Slater (1990, p. 21) put it, a company must understand not only the cost and revenue dynamics of its immediate target buyer rms, but also

Received: October 2008 Revised: May 2009 Accepted: September 2009 The authors would like to thank Karen Janssen, Gerben van Egdom and Pim Sebok for their assistance with the data collection.

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 26/2 (2011) 72 80 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited [ISSN 0885-8624] [DOI 10.1108/08858621111112258]

72

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

the cost and revenue dynamics facing the buyers buyers, from whose demand the demand of the immediate market is derived. It is also in line with several calls for closer attention to other stakeholders than just the immediate customer (Greenley and Foxall, 1996; Maignan and Ferrel, 2004; Matsuno et al., 2005). Unfortunately, these calls have not been heeded yet; downstream customers are still ignored in market orientation studies, leaving B2B rms in need of actionable guidelines on how to deal with these downstream customers. This paper explores the neglected implications of derived demand. It investigates: . to what extent rms near the beginning of the supply chain are oriented towards downstream customers; . the problems they encounter in extending their market orientation to include downstream customers; and . how they deal with these problems. This study contributes to the extant literature on market orientation by showing how an extended market orientation differs from a traditional market orientation and what this means to rms. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, it discusses the theoretical background focusing on the relationship between rms and their downstream customers in various streams of research. Next, it presents the methodology used in the exploratory study and its major ndings. It concludes with a discussion of the studys implications and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical background

Despite repeated calls for broadening the market orientation construct (Greenley and Foxall, 1996; Maignan and Ferrel, 2004; Matsuno et al., 2005) the question how rms deal with downstream customers has largely been ignored. In line with the concept of market-oriented behavior (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990), an orientation to downstream customers is here dened as the generation, organization-wide dissemination and responsiveness to intelligence about downstream customers. While this is conceptually very similar to traditional market orientation, an orientation to downstream customers is different because B2B rms are by denition separated from their downstream markets by their immediate customers. Especially for suppliers of entering goods (such as components and raw materials) that become part of their customers products this may result in problems related to: . gathering information about supply chain structure and individual downstream customers (such as supply chain levels, key parties at each level, decision-making processes, product requirements and the level and variability of downstream demand) and disseminating this information to all relevant parties within the rm; and . providing downstream customers with relevant information, i.e. developing effective relationships and targeting them with marketing programs. In other words, the distance between a supplier and its downstream customers complicates their interaction. This suggests the need for a closer look at how the traditional market orientation concept may be extended. While the literature hardly mentions how rms should deal with downstream customers, certain elements of downstream customer orientation or related issues have been studied. For example, some authors discuss the inuence of downstream 73

customers by focusing on the bullwhip effect, referring to the phenomenon that orders to the supplier tend to have larger variance than sales to the buyer (i.e. demand distortion), and the distortion propagates upstream in an amplied form (i.e. variance amplication) (Lee et al., 1997, p. 546). This bullwhip effect complicates demand forecasting, increases costs and reduces customer service levels. McCullen and Towill (2002, p. 178) concluded that the bullwhip effect is still alive and travels well over long distances. Others looked at specic methods to approach downstream customers. For example, the marketing literature on pull strategies describes how demand from immediate customers may be stimulated by targeting downstream customers (Paliwoda and Bonaccorsi, 1993) or by using ingredient branding, i.e. branding aimed at downstream customers (McCarthy and Norris, 1999; Venkatesh and Mahajan, 1997). The business network literature acknowledges the importance of indirect relationships (Mattsson, 1987), but largely ignores the role of downstream customers. For instance, while many researchers investigated the involvement of suppliers, competitors, distributors and other third parties in NPD (Gemunden et al., 1996; Hakansson, 1987; Ford, 1997), the role of downstream customers has been neglected. This is a glaring oversight because new products that do not fulll the needs of downstream customers are not likely to succeed (Jones and Ritz, 1991; Mesak and Darrat, 2004). The supply chain management (SCM) literature explicitly addresses interactions between organizations at different levels of the supply chain. While some argue that rms may also ourish using a rather narrow customer horizon, excluding most downstream customers (Holmen and Pedersen, 2003; Storer et al., 2003), SCMs central tenet is that rms in a supply chain affect the performance of other supply chain members (Mentzer et al., 2001). This implies the need to understand the entire supply chain and cooperate and coordinate with other member rms (Cooper et al., 1997; Spekman et al., 1998; Skjoett-Larsen et al., 2003; Gundlach et al., 2006, Soroor et al., 2009). For instance, Holmen et al. (2007) describe how rms may use supply network initiatives to create a supply network. The SCM literature also stresses the role and importance of power (e.g. Butaney and Wortzel, 1988; Hingley, 2005) and trust (e.g. Myhr and Spekman, 2005). But although a supply chain implies interaction between multiple actors, empirical studies typically take a dyadic approach focusing on buyer-seller relationships in the context of a supply chain and ignoring issues concerning the supply chain as a whole (Carter and Ellram, 2003). A notable exception is a study of the orientation of the whole supply chain on the end-consumer (Grunert et al., 2005). The present study extends this study by focusing on the orientation of one rm (rather than a whole supply chain) on all downstream customers (not necessarily the end-consumer) and investigating how rms deal with the intricacies of derived demand.

Research method

Treading on relatively unfamiliar grounds, this study used an exploratory research method. In-depth interviews with managers from upstream suppliers were used to investigate the extent to which they are aware of downstream customers and take them into account. To increase the likelihood that suppliers are aware of and working with downstream

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

customers, we selected suppliers positioned near the beginning of their supply chains. In addition, the selected rms represent various industries (bers, food ingredients, metal, plastics) to capture a diverse set of contexts. The study consists of two phases. The rst phase used a rather broad approach to the topic, using a semi-structured list of issues to explore the role of downstream customers and identify relevant issues. The interviews covered rm demographics, supply chain structures, the extent to which suppliers work with downstream customers, problems experienced in dealing with downstream customers, strategies for dealing with them and their success. Because the rst phase revealed that issues with downstream customers are especially relevant when rms are developing and marketing new products, the second phase zoomed in on the most relevant issues in this context. In each respondent rm, a recently introduced new product was selected and respondents were asked to discuss the roles of immediate and downstream customers in developing and marketing that product. Firms were added to the sample until the results converged and additional interviews yielded no substantial new insight (Eisenhardt, 1989). A total of 11 products from nine rms were investigated, including a coating, a robot for agriculture, an ingredient for cattle feed and a plastic. This second phase rened the ndings from the rst phase. In total, i.e. for both phases of the study, we interviewed 31 respondents from 21 rms. We asked for the person most knowledgeable about the rms customers and marketing efforts as our respondent. In most rms, this was a senior manager with a job title that clearly indicated his/her involvement with the rms markets and customers (such as business unit managers or marketing managers). In other rms, the most suitable respondent turned out to be a general manager or R&D manager. The interviews typically lasted one-and-a-half to two hours. All interviews were taperecorded. Detailed interview reports were sent to the respondents, who checked them for mistakes or omissions and offered further explanation for ambiguous issues. The interview reports were coded using descriptive, interpretive and pattern codes (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Familiar techniques such as tables and owcharts (Miles and Huberman, 1994) were used to explore ideas and shape the analysis. Following qualitative inquiry practices, we coded our data iteratively and constantly rened our interpretations on the basis of subsequent interview data. When subsequent data did not raise any questions about our interpretations or add anything new to our understanding, we agreed that we had reached saturation.

downstream customers problematic (or shied away from even trying) because of several barriers related to gathering information from and providing information to downstream customers. These barriers as well as how rms try to deal with these barriers are discussed below. Value of the product to downstream customers The ndings show that many rms wanting to connect to their downstream customers are having difculties with that because downstream customers are not always interested in discussing or co-developing a new product. Information offered to downstream customers must be meaningful to them and demonstrate that the product has signicant downstream value. But this may be problematic for two reasons. First, the products benets to downstream customers may be very indirect and hard to quantify. While a new product may be critical to the immediate customers product, the new products contribution is likely to dilute further down the value chain. For example, one respondent explained that their coating improved the quality of specic components, but when these components are used in electric shavers they account for only 60 eurocents out of a total consumer price of 150 euro. The coating does add value by lowering costs, improving the look and feel of the nal product and increasing its durability, but it represents only a very small part of the consumer product evaluated by downstream customers. Second, many downstream customers lack the expertise to assess the value of a new upstream product. Several respondents mentioned that downstream customers frequently need to be educated about the value of upstream products. For instance, a supplier to the apparel industry found that most shirt manufacturers (downstream customers) do not know how a starch specialty used by a blender (immediate customer) affects the quality and cost of their shirts. Another respondent, in the food industry, emphasized that small downstream customers tend to focus on the higher price of an ingredient, ignoring the benets of these ingredients because they lack the skill to recognize these benets. Some large downstream customers do possess the skill to assess the value of ingredients because they have specialized departments staffed by experts, which makes it easier to convince them to use the higher-price ingredients. A lack of perceived value obviously hinders the communication and cooperation between the supplier and its downstream customers. Many respondents stated that downstream customers being unable to assess the value of their upstream products is the number one reason for not employing ingredient branding: downstream customers were believed not to see the relevance of the ingredient, let alone the brand of the ingredient. We also found that the further down the supply chain the more problems downstream customers are likely to have with correctly assessing the value of the product, simply because it is likely to represent only a smaller portion of their product and to be less related to their own elds of expertise. This suggests the following propositions: P1. Upstream suppliers are more oriented towards downstream customers when these customers are able to assess the value of the upstream product. Downstream customers are more likely to be able to assess the value of an upstream product when the downstream customer is less far down the supply chain.

Results

All respondents were well aware of the importance of downstream customers, but this awareness did not always cause them to pay special attention to them. Some managers accepted the inuence of downstream customers as an inherent characteristic of their supply chains and felt that it was outside their control. In the words of one respondent: many people [in our rm] just focus on our customers and dont look any further. It would only make things more complicated and there is little we can do about it. Others realized that downstream customers complicate product development and marketing by requiring suppliers to look beyond their immediate customers. Firms found involving 74

P2.

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

While this may be taken to suggest that rms near the beginning of the supply chain depend on downstream customers ability to assess upstream value, several respondents indicated that they try to change this by educating their downstream customers. We found three basic approaches. First, some rms engage in market research on downstream markets to learn more about these markets and to be better equipped to target downstream customers and convince them to switch to their ingredient. Armed with information about downstream customer demand for products containing the upstream ingredient, rms are better able to convince both downstream customers and immediate customers to switch to their ingredients. For instance, a manufacturer of food ingredients used the results from consumer research to convince skeptic downstream customers (supermarket chains) and immediate customers (food manufacturers) that consumers are ready for functional foods (food with specic health enhancing ingredients, like milk with extra calcium). This strategy requires substantial investments, especially when the downstream markets are very different from the immediate markets with which the rm is familiar. Second, some respondents indicated that they had developed supply chain value models that demonstrate how each supply chain member stands to benet from adopting (a product with) the suppliers ingredient by quantifying the upstream products impact on the downstream customers business. For instance, a supplier of ingredients for the apparel industry used such models to convince downstream customers that a higher-quality starch increases effectiveness and lowers costs. The development of these models required a lot of time and effort, as well as detailed information about manufacturing processes used throughout the chain. To develop them, the supplier even hired people specialized in the manufacturing processes of downstream customers. Third, some rms try to make the value of the upstream product more explicit by showing immediate and downstream customers how to use the product. Frequently, a customers reluctance to adopt a new product is partly due to his inability to implement it in manufacturing. One respondent related how a new ber caused problems for both immediate and downstream customers because it required modications to existing manufacturing processes. The ber supplier decided to build an application lab to study the various customer manufacturing processes and advise immediate and downstream customers on how to use the new ber. Attitude of immediate customers The second barrier identied in this study is the attitude of immediate customers towards a suppliers initiatives to collect information from or provide information to downstream customers. Many rms near the beginning of the supply chain rely on their immediate customers for market intelligence, making them very dependent on their immediate customers and sometimes resulting in limited or distorted information. Several respondents experienced signicant problems with demand forecasting because they had insufcient information about downstream markets. In some industries customers do not want to provide information about the demand for their products. This is particularly true for resellers that depend on uctuations in supply and demand for their income. For instance, in the metal industry information about the demand for certain types of metal is not likely to be shared. 75

Immediate customers may also resist marketing efforts directed at downstream customers. They want control over the selection of components and do not want suppliers to create a pull effect from downstream customers. Indeed, several respondents stated that they refrained from any marketing activities directed at downstream customers because they do not want to offend their immediate customers. For example, ingredient branding requires immediate customers to display the ingredients brand and they are not always willing to cooperate. One of our respondents, a supplier to the automotive industry, suggested ingredient branding to its immediate customers and was ercely rejected. Other respondents seriously considered e-commerce, but most of them worried about the reactions from immediate customers, since these immediate customers are likely to perceive the rms e-channel as a direct competitor. Clearly, many rms are careful not to upset their immediate customers by approaching downstream customers. As one respondent put it: We are very restrained in that respect: we only approach our downstream customers when we are absolutely sure we wont get into any problems with our immediate customers. Some even said that they were unwilling to bring up the issue because of feared negative reactions from immediate customers. This was especially the case for rms that were highly dependent on their immediate customers. Nevertheless, several respondents found their immediate customers to be less antagonistic than described above or even supportive. Supportive immediate customers come in two kinds. Some cooperate (e.g. by sharing information about downstream customers, jointly developing products for downstream customers or marketing the new product to downstream customers), but still remain the single or main channel of communication between supplier and downstream customers. In these cases the immediate customers act as a proxy for downstream customers, thus staying in control of the relationship. Other immediate customers did allow direct access to downstream customers. Especially complex products frequently require direct relationships with downstream customers and relying on third parties (such as distributors who are less knowledgeable about the products technical characteristics) may be risky and jeopardize the rms reputation. Whether immediate customers functioned as intermediate between the supplier and its downstream customers or facilitated direct communication between them, in both cases the supplier can increase its orientation towards downstream customers, i.e. to obtain information about downstream customers and to provide information to downstream customer. But with immediate customers acting as intermediates the collected information about downstream customers may be distorted. These ndings suggest that immediate customers may hold different attitudes towards their suppliers attempts to be focused on downstream customers. They can be positioned on a spectrum ranging from unsupportive to supportive, with unsupportive immediate customers prohibiting any kind of information exchange between supplier and downstream customers and supportive immediate customers providing information about downstream customers, granting access to them and performing marketing (research) activities on behalf of the supplier. An immediate customers attitude towards supplier activities aimed at downstream customers appears to depend on the customers relative market power (which is

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

based on variables such as the customers share of wallet and the availability of alternatives for both parties) and its overall level of marketing sophistication. The immediate customers attitude is especially likely to impact the rms information exchange with downstream customers when the rm is dependent on the immediate customer. This results in the following propositions: P3. Firms are more oriented towards downstream customer when immediate customers support such initiatives. The attitudes of immediate customers have a stronger effect on the rms orientation towards downstream customers when the rm strongly depends on its immediate customers.

P4.

Capability to interact with downstream customers While most respondents acknowledged the importance of working with downstream customers, we found that only a few rms actually had established direct relationships with downstream customers. One reason for this lack of direct connections with downstream customers is that many suppliers lack the capability to interact with downstream customers. Because working with downstream customers requires detailed information about unfamiliar markets and substantial resources they prefer to stick to their knitting. To effectively communicate with downstream customers rms need several capabilities. First of all, they must be able to adapt their marketing (research) activities to completely different settings. This is especially the case when they approach the ultimate downstream customer, i.e. consumers, because this requires them to carry out consumer marketing (research), which involves a whole new set of skills. Some of the rms decided to leave consumer marketing and research to their customers further down the supply chain, but others picked up the gauntlet. For instance, a food ingredients supplier hired a manager with extensive consumer marketing experience to investigate and target the consumer market. Another food ingredients supplier beneted from the fact that it is part of a larger organization that includes business units with consumer marketing experience. Second, because rms near the beginning of the supply chain typically sell products that are used as ingredients for various other products, they must be able to monitor a wide range of industries affected by a wide range of different factors. While they may be able to quickly chart their most relevant supply chains, they frequently experience great difculty in gathering in-depth information about downstream customer requirements as input for product development and marketing. A respondent from a metals supplier stated that it is almost impossible to obtain accurate demand forecasts for all industries they supply to since they are all affected by different industry-specic factors. While the demand for cans is largely determined by the availability of fruits and vegetables, which depends on weather conditions in several countries, the demand for cars depends on various economic factors that differ per region. Collecting and analyzing such detailed information for several industries is a daunting task. Especially in the case of very diverse downstream markets the required information system quickly grows to unwieldy proportions and complexity. A chemicals supplier noted that while success in the automotive industry requires up-to-date information on car development 76

projects, the packaging industry demands close attention to uctuations in prices and demand. As both markets are crucial to the rm but at the same time require completely different types of information, the rm decided to develop two separate information systems. Third, rms must be able to identify the right decision makers within each supply chain. For instance, a manufacturer of bers used in bullet-proof helmets wondered whether it should target the end users (e.g. Ministries of Defense) or intermediate customers such as weavers (who weave the ber into cloth), pressers (who press cloth into bare helmets) or helmet manufacturers (who add the inner helmet and fastenings). The importance of such a capability is illustrated by a manufacturer of uid handling products for the automotive industry that only targeted its immediate customers. It lost business to a competitor that actively sold a car manufacturer (i.e. a downstream customer) on the use of its ingredient, which caused the car manufacturer to overrule its component supplier and demand a product with the competitors ingredient. The losing manufacturer explained the loss of the customer succinctly: We did not have access to the real decision maker. Especially key decision makers located far down the supply chain may be difcult to identify. These three key capabilities of implementing a downstream customer orientation are formally captured in the following propositions: P5. Firms are more oriented towards downstream customers when they are able to adapt their marketing (research) activities to new settings. Firms are more oriented towards downstream customers when they are able to manage information about a wide set of different industries. Firms are more oriented towards downstream customers when they are able to identify key decision makers in the supply chain.

P6.

P7.

These propositions are especially relevant for rms near the beginning of the supply chain because they tend to be confronted with more unfamiliar settings, a large variety of downstream markets and more problems with identifying key decision makers.

Discussion

This study contributes to the extant literature about market orientation by investigating three related issues: 1 the extent to which rms near the beginning of the supply chain are oriented towards downstream customers; 2 the problems they encounter when extending their market orientation to include downstream customers; and 3 the strategies to deal with these problems. This is the rst study that expands the concept of market orientation to downstream customers and thus contributes to the extant literature on both market orientation and B2B marketing. It explores not only the extent of B2B suppliers orientation towards downstream customers, but also the problems in implementing such an orientation and strategies that increase the likelihood of success. Our ndings suggest that rms near the beginning of the supply chain know that downstream customers inuence the success of their new products, and thus their long-term survival, but at the same time many fail to act on this. Thus, in terms of recognition

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

rms near the beginning of the supply chain are fairly oriented to downstream customers, but not in terms of actual behavior. This reects the market orientation literature, which conceptualizes market orientation from both behavioral and cognitive perspectives (Homburg and Pesser, 2000) and which notes that several barriers may prevent a marketoriented culture from resulting in market-oriented behavior (Matsuno et al., 2005). This study contributes to this literature by showing that additional barriers prevent rms from extending the traditional market orientation concept and implementing an orientation towards downstream customers. Our study identied several barriers that may prevent a rm from implementing a downstream customer orientation, either related to downstream customers (the degree to which downstream customers recognize the value of upstream products), to the immediate customers (the degree to which immediate customers are unsupportive to the rm), or to the rm itself (capabilities needed for a downstream customer orientation). This emphasizes that, unlike the traditional market orientation, an orientation towards downstream customers requires a multi-actor perspective. A rms ability to effectively work with downstream customers largely depends on the immediate customers willingness to cooperate. Even when downstream customers are convinced of an upstream products value, immediate customers may resist the suppliers downstream activities. This nding echoes the role of dependence as a key factor in understanding supply chain relationships (Grunert et al., 2005; Palmer, 2007). Managerial implications The results from this study describe several strategies that rms may employ to deal with these barriers. Implementation of a downstream customer orientation starts with charting the rms most important supply chains in terms of supply chain levels, key players per level and upstream product value per level. This is a major effort since most upstream suppliers are unfamiliar with downstream markets and the value downstream customers derive from upstream products. The construction of supply chain value models that specify their upstream products value at various levels of the supply chain may be helpful here (Anderson and Narus, 1998; Matthyssens et al., 2009). In promoting the use of analytics, Davenport (2006, p. 104) states that the most procient analytics practitioners dont just measure their own navels they also help customers and vendors measure theirs. In some cases, providing information is not enough and customers may only be persuaded when the supplier helps them in using the upstream product in their manufacturing systems. Application labs can be used to help customers and learn about manufacturing requirements further down the supply chain. Because immediate customers may feel threatened by and resist supplier initiatives towards downstream customers, suppliers must defuse such fears. For instance by explaining the benets of a downstream customer orientation to immediate customers (e.g. in terms of improved products and increased market acceptance of new products because of involvement and commitment from downstream customers). But this is no easy task. Especially in markets with strong price competition, immediate customers have little incentive to cooperate. Some of the rms investigated tried to change the rules of the game by persuading the most receptive customers to focus on added value and cooperation rather 77

than price and competition, but this is a process of delicate sensing and probing. However, while it may be tempting to implement a downstream customer orientation, it is not always feasible. Our study indicated that such initiatives may seriously damage relationships with immediate customers. Also, rms may lack the required resources and skills to adequately approach downstream customers directly; a downstream customer orientation needs to be supplemented by the required marketing capabilities (Morgan et al., 2009). In such cases, the immediate customer may serve as a proxy of downstream customers, i.e. to provide the upstream rm with information about its own customers and to target the downstream customers with information from its upstream supplier. Obviously, this requires the immediate customer to have detailed information about downstream customers and to be willing to share this information with the supplier. Also, in these situations upstream suppliers still need to carefully assess the quality of their immediate customers information about downstream customers. Although this study did not formally investigate the relationship between an orientation of downstream customers and new product performance, the exploratory ndings suggest that both an orientation towards immediate customers and an orientation towards downstream customers are needed for new product success. While a traditional market orientation (towards immediate customers) may result in products that offer value to immediate customers, they do not necessarily match the requirements of downstream customers. The whole supply chain needs to adopt a new product in order for a supplier to be truly successful (Jones and Ritz, 1991; Mesak and Darrat, 2004). When downstream customers embrace a product concept, their acceptance can be used to persuade immediate customers as well. But an exclusive focus on downstream customers may result in products that are resisted by the rms immediate customers. Thus, upstream suppliers need to be focused on both immediate customers and downstream customers. Limitations and future research This is the rst study to provide a comprehensive overview of what it means to extend a traditional market orientation to include downstream customers. The studys ndings resulted in several propositions that explain the drivers of an upstream suppliers orientation towards downstream customers. However, this study was exploratory in nature and only looked at a limited numer of B2B suppliers of entering goods, using face-to-face interviews with key informants. Thus, one avenue for future research would be to test these propositions through conrmatory studies using larger samples of rms in several different industries and contexts. For instance, future researchers should investigate the downstream customer orientations of B2B suppliers of goods that do not become part of their customers products. In addition, future research might study the downstream customer orientation of manufacturers of consumer products that deal with distributors and large key retail accounts. In addition, our ndings revealed several factors that hinder a rms orientation towards downstream customers and indicate how rms may deal with them. Future research might focus on developing the tools and techniques that managers may use to tackle these problems. Especially useful would be tools and techniques to help managers identify the key

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

downstream customers to focus on. When B2B suppliers are able to measure and communicate the value offered by their ingredients to downstream customers, another relevant issue is how to share the added value among all relevant parties. Future researchers might identify the variables that determine a suppliers capability to capture the value created for immediate and downstream customers, as well as the various strategies to appropriate value (Wagner and Lindemann, 2008). Other researchers might want to focus on the variables that determine an immediate customers willingness to cooperate with a supplier in targeting downstream customers. Finally, future research may focus on interaction with downstream customers in specic contexts, such as product development, and identify best practices concerning the involvement of downstream customers and the management of effective downstream relationships. In this paper, we have expanding the concept of market orientation to include downstream customers. The ideas and ndings presented here offer numerous fruitful suggestions for further research into the intricacies of a suppliers downstream customer orientation. Such research will contribute to B2B suppliers market orientation and rm performance.

References

Anderson, J.C. and Narus, J.A. (1998), Business marketing: understand what customers value, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 76 No. 6, pp. 53-65. Atuahene-Gima, K. (1995), An exploratory analysis of the impact of market orientation on new product performance; a contingency approach, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 275-93. Butaney, G. and Wortzel, L.H. (1988), Distributor power versus manufacturer power: the customer role, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 52 No. 1, pp. 52-63. Carter, C.R. and Ellram, L.M. (2003), Thirty-ve years of The Journal of Supply Chain Management: where have we been and where are we going?, The Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 27-39. Cooper, M.C., Lambert, D.M. and Pagh, J.D. (1997), Supply chain management: more than a new name for logistics, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 1-14. Davenport, T.H. (2006), Competing on analytics, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 84 No. 1, pp. 98-107. Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989), Building theories from case study research, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 532-50. Fern, E.F. and Brown, J.R. (1984), The industrial/consumer marketing dichotomy: a case of insufcient justication, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 48 No. 2, pp. 68-77. Ford, D. (Ed.) (1997), Understanding Business Markets: Interaction, Relationships and Networks, The Dryden Press, London. Gemunden, H.G., Ritter, T. and Heydebreck, P. (1996), Network conguration and innovation success: an empirical analysis in German high-tech industries, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 13 No. 5, pp. 449-62. Greenley, G.E. and Foxall, G.R. (1996), Consumer and nonconsumer stakeholder orientation in UK companies, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 35 No. 2, pp. 105-16. 78

Grunert, K.G., Fruensgaard Jeppesen, L., Risom Jespersen, K., Sonne, A-M., Hansen, K., Trondsen, T. and Young, J.A. (2005), Market orientation of value chains: a conceptual framework based on four case studies from the food industry, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 39 Nos 5/6, pp. 428-55. Gundlach, G.T., Bolumole, Y.A., Eltantawy, R.A. and Frankel, R. (2006), The changing landscape of supply chain management, marketing channels of distribution, logistics and purchasing, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 21 No. 7, pp. 428-38. Hakansson, H. (Ed.) (1987), Industrial Technological Development: A Network Approach, Croom Helm, London. Han, J.K., Kim, N. and Srivastava, R.K. (1998), Market orientation and organizational performance: is innovation the missing link?, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 62 No. 4, pp. 30-45. Hingley, M.K. (2005), Power to all our friends? Living with imbalance in supplier-retailer relationships, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 34 No. 8, pp. 848-58. Holmen, E. and Pedersen, A-C. (2003), Strategizing through analyzing and inuencing the network horizon, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 32 No. 5, pp. 409-18. Holmen, E., Pedersen, A-C. and Jansen, N. (2007), Supply network initiatives a means to reorganise the supply base?, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 22 No. 3, pp. 178-86. Homburg, C. and Pesser, C. (2000), A multiple-layer model of market-oriented organizational culture: measurement issues and performance outcomes, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 37 No. 5, pp. 449-62. Jones, J.M. and Ritz, C.J. (1991), Incorporating distribution into new product diffusion models, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 8, pp. 91-112. Kohli, A.K. and Jaworski, B.J. (1990), Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54 No. 2, pp. 1-18. Lee, H.L., Padmanabhan, V. and Whang, S. (1997), Information distortion in a supply chain: the bullwhip effect, Management Science, Vol. 43 No. 4, pp. 546-58. Li, T. and Calantone, R.J. (1998), The impact of market knowledge competence on new product advantage: conceptualization and empirical examination, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 62 No. 3, pp. 13-29. McCarthy, M.S. and Norris, D.G. (1999), Improving competitive position using branded ingredients, Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 267-85. McCullen, P. and Towill, D. (2002), Diagnosis and reduction of bullwhip in supply chains, Supply Chain Management, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 164-79. Maignan, I. and Ferrel, O.C. (2004), Corporate social responsibility and marketing: an integrative framework, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 3-19. Matsuno, K., Mentzer, J.T. and Rentz, J.O. (2005), A conceptual and empirical comparison of three market orientation scales, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58 No. 1, pp. 1-8. Matthyssens, P., Vandenbempt, K. and Goubau, C. (2009), Value capturing as a balancing act, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 56-60. Mattsson, L-G. (1987), Indirect relations in industrial networks; a conceptual analysis of their signicance for the

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

rms strategic activities, in Belk, R.W. et al. (Eds), Marketing Theory: Proceedings of the 1987 AMA Winter Educators Conference, AMA, Chicago, pp. 127-32. Mentzer, J.T., DeWitt, W., Keebler, J.S., Min, S., Nix, N.W., Smith, C.D. and Zacharia, Z.G. (2001), Dening supply chain management, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 1-25. Mesak, H.I. and Darrat, A.F. (2004), An empirical inquiry into new subscriber services under interdependent adoption processes, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 180-92. Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994), Qualitative Data Analysis; An Expanded Sourcebook, Sage, Beverly Hills, CA. Morgan, N.A., Vorhies, D.W. and Mason, C.H. (2009), Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and rm performance, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 30 No. 8, pp. 909-20. Myhr, N. and Spekman, R.E. (2005), Collaborative supplychain partnerships built on trust and electronically mediated exchange, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 20 Nos 4/5, pp. 179-86. Narver, J.C. and Slater, S.F. (1990), The effect of a market orientation on business protability, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54 No. 4, pp. 20-35. Paliwoda, S.J. and Bonaccorsi, A.J. (1993), Systems selling in the aircraft industry, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 155-60. Palmer, R. (2007), The transaction-relational continuum: conceptually elegant but empirically denied, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 22 No. 7, pp. 439-51. Skjoett-Larsen, T., Thernoe, C. and Andresen, C. (2003), Supply chain collaboration, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 33 No. 6, pp. 531-50. Soroor, J., Tarokh, M.J. and Shemshadi, A. (2009), Theoretical and practical study of supply chain coordination, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 131-42. Spekman, R.E., Kamauff, J.W. and Myhr, N. (1998), An empirical investigation into supply chain management: a perspective on partnerships, Supply Chain Management, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 53-67. Storer, C.E., Holmen, E. and Pedersen, A.-C. (2003), Exploration of customer horizons to measure understanding of netchains, Supply Chain Management, Vol. 8 No. 5, pp. 455-66. Venkatesh, R. and Mahajan, V. (1997), Products with branded components: an approach for premium pricing and partner selection, Marketing Science, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 146-65. Wagner, S.M. and Lindemann, E. (2008), Determinants of value sharing in channel relationships, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 23 No. 8, pp. 544-53.

management. He has published in Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Organization Studies, Journal of Service Management, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Journal of Business Research, and International Journal of Research in Marketing, among others. Bas Hillebrand is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: B.Hillebrand@fm.ru.nl Wim G. Biemans is Associate Professor of Innovation at the Faculty of Economics and Business of the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. His research focuses on B2B marketing and innovation. He has published several books and numerous academic papers in the major journals in these areas, such as Journal of Product Innovation Management, Technovation, R&D Management, International Journal of Innovation Management, Industrial Marketing Management, and Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. In addition, he is a frequent reviewer for these journals.

Executive summary and implications for managers and executives

This summary has been provided to allow managers and executives a rapid appreciation of the content of the article. Those with a particular interest in the topic covered may then read the article in toto to take advantage of the more comprehensive description of the research undertaken and its results to get the full benet of the material presented. Distant relatives are the best kind and the further the better said American humorist Kin Hubbard, but it is no cause for amusement when distance gets in the way of effective cooperation and collaboration with your relatives in the supply chain. While rms are aware of the importance of downstream customers, they frequently fail to establish effective relationships with them. The distance between a supplier and its downstream customers complicates their interaction. Most business-to-business marketing textbooks dene derived demand, explain how it complicates demand forecasting, and argue that business marketers should look at both their immediate customers and the downstream markets served by them. But they fail to go beyond these general observations and offer insight into the consequences of derived demand, the managerial challenges it causes and solutions to deal with them. Most upstream suppliers are unfamiliar with downstream markets and the value downstream customers derive from upstream products. Many rms near the beginning of the supply chain rely on their immediate customers for market intelligence, making them very dependent on these immediate customers and sometimes resulting in limited or distorted information. Many rms have signicant problems with demand forecasting because they have insufcient information about downstream markets. In some industries customers do not want to provide information about the demand for their products. This is particularly true for resellers that depend on uctuations in supply and demand for their income. For instance, in the metal industry, information about the demand for certain types of metal is not likely to be shared. By interviewing managers from upstream suppliers about the extent to which they are aware of downstream customers and take them into account, Bas Hillebrand and Wim Biemans explore the neglected implications of derived 79

About the authors

Bas Hillebrand is Associate Professor of Marketing at the Nijmegen School of Management, Institute for Management Research of the Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands. He studied business administration at Tilburg University and holds a PhD from the University of Groningen. His research interests include new product management, adoption research, and relationship

Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study Bas Hillebrand and Wim G. Biemans

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing Volume 26 Number 2 2011 72 80

demand. They investigate to what extent rms near the beginning of the supply chain are oriented towards downstream customers, the problems they encounter in extending their market orientation to include downstream customers, and how they deal with these problems. Implementation of a downstream customer orientation starts with charting the rms most important supply chains in terms of supply chain levels, key players per level and upstream product value per level. The construction of supply chain value models that specify their upstream products value at various levels of the supply chain may be helpful. In some cases, providing information is not enough and customers may only be persuaded when the supplier helps them in using the upstream product in their manufacturing systems. Application labs can be used to help customers and learn about manufacturing requirements further down the supply chain. Because immediate customers may feel threatened by and resist supplier initiatives towards downstream customers, suppliers must defuse such fears. For instance by explaining the benets of a downstream customer orientation to immediate customers (e.g. in terms of improved products and increased market acceptance of new products because of involvement and commitment from downstream customers). But this is no easy task. Especially in markets with strong price competition, immediate customers have little incentive to cooperate. Some of the rms investigated in this study tried to change the rules of the game by persuading the most receptive customers to focus on added value and cooperation rather than price and competition, but this is a process of delicate sensing and probing. While it may be tempting to implement a downstream customer orientation, it is not always feasible. Such initiatives

may seriously damage relationships with immediate customers. Also, rms may lack the required resources and skills to adequately approach downstream customers directly; a downstream customer orientation needs to be supplemented by the required marketing capabilities. In such cases, the immediate customer may serve as a proxy of downstream customers, i.e. to provide the upstream rm with information about its own customers and to target the downstream customers with information from its upstream supplier. Obviously, this requires the immediate customer to have detailed information about downstream customers and to be willing to share this information with the supplier. Also, in these situations upstream suppliers still need to carefully assess the quality of their immediate customers information about downstream customers. Both an orientation towards immediate customers and an orientation towards downstream customers are needed for new product success. While a traditional market orientation (towards immediate customers) may result in products that offer value to immediate customers, they do not necessarily match the requirements of downstream customers. The whole supply chain needs to adopt a new product in order for a supplier to be truly successful. When downstream customers embrace a product concept, their acceptance can be used to persuade immediate customers as well. But an exclusive focus on downstream customers may result in products that are resisted by the rms immediate customers. Thus, upstream suppliers need to be focused on both immediate customers and downstream customers. (A precis of the article Dealing with downstream customers: an exploratory study. Supplied by Marketing Consultants for Emerald.)

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

80

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shedding The Commodity MindsetDocument5 pagesShedding The Commodity MindsetDaxPas encore d'évaluation

- In Holland V Hodgson The ObjectDocument5 pagesIn Holland V Hodgson The ObjectSuvigya TripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Consulting Interview Case Preparation: Frameworks and Practice CasesD'EverandConsulting Interview Case Preparation: Frameworks and Practice CasesPas encore d'évaluation

- QUARTER 3, WEEK 9 ENGLISH Inkay - PeraltaDocument43 pagesQUARTER 3, WEEK 9 ENGLISH Inkay - PeraltaPatrick EdrosoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Slater and Narver 1998Document7 pagesSlater and Narver 1998Anuj KaulPas encore d'évaluation

- An Assessment of Customer Service in Business-To-BDocument20 pagesAn Assessment of Customer Service in Business-To-BAcodor DoorPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Wholesale Brands For Buyer Loyalty: A Transaction Cost PerspectiveDocument9 pagesThe Role of Wholesale Brands For Buyer Loyalty: A Transaction Cost PerspectiveNeeraj VishwakarmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Business To Business Marketing 4th Edition by Brennan ISBN Solution ManualDocument20 pagesBusiness To Business Marketing 4th Edition by Brennan ISBN Solution Manualfrancisco100% (19)

- Solution Manual For Business To Business Marketing 4Th Edition by Brennan Isbn 1473973449 978147397344 Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesSolution Manual For Business To Business Marketing 4Th Edition by Brennan Isbn 1473973449 978147397344 Full Chapter PDFmary.graf929100% (13)

- Literature Review On Relationship Marketing PDFDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Relationship Marketing PDFafmzxpqoizljqo100% (1)

- Pricing PurchasingDocument11 pagesPricing PurchasingDesrina Putri MarlipPas encore d'évaluation

- Business To Business Marketing 4th Edition Brennan Solutions Manual DownloadDocument6 pagesBusiness To Business Marketing 4th Edition Brennan Solutions Manual DownloadCoryRogerswpak100% (35)

- Customer ServicesDocument19 pagesCustomer ServicesAnda StancuPas encore d'évaluation

- Business To Business Marketing EssayDocument5 pagesBusiness To Business Marketing EssayLeonardo CalvintPas encore d'évaluation

- Differences in Exchange Situations in Fast Moving Consumer Goods' MarketsDocument37 pagesDifferences in Exchange Situations in Fast Moving Consumer Goods' MarketsRahul KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- StorbackaDocument15 pagesStorbackaRobin BishwajeetPas encore d'évaluation

- Blurring TheDocument9 pagesBlurring ThefarhanadaudPas encore d'évaluation

- Solution Manual For Business To Business Marketing 4th Edition by Brennan ISBN 1473973449 9781473973442Document36 pagesSolution Manual For Business To Business Marketing 4th Edition by Brennan ISBN 1473973449 9781473973442juliebeasleywjcygdaisn100% (26)

- Balancing MarqueringDocument11 pagesBalancing Marqueringlucia zegarraPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Manufacturer's Salespeople in Inducing Brand Advocacy by Retail Sales AssociatesDocument15 pagesRole of Manufacturer's Salespeople in Inducing Brand Advocacy by Retail Sales AssociatesAtri RoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Foreign Distributors: Chapter Summary & Case StudyDocument23 pagesForeign Distributors: Chapter Summary & Case StudyEka DarmadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter-1: An Analytical Study On Distribution Strategies and Customer Satisfaction of Mak Lubricants PVT LTDDocument8 pagesChapter-1: An Analytical Study On Distribution Strategies and Customer Satisfaction of Mak Lubricants PVT LTDVaishnavi pandurangPas encore d'évaluation

- ArticleDocument9 pagesArticleFizza ShahidPas encore d'évaluation

- Business To Business Marketing 4th Edition Brennan Solutions ManualDocument21 pagesBusiness To Business Marketing 4th Edition Brennan Solutions ManualAnthonyJacksonekdpb100% (17)

- MArket ResearchDocument10 pagesMArket ResearchNisha GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- CRM-Unit IDocument40 pagesCRM-Unit IOsamaMazhariPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolving Pricing Practices: The Role of New Business Models: Dhruv Grewal and Anne L. RoggeveenDocument4 pagesEvolving Pricing Practices: The Role of New Business Models: Dhruv Grewal and Anne L. RoggeveencharanPas encore d'évaluation

- An International Study of The Impact of B2C Logistics Service Quality On Shopper Satisfaction and LoyaltyDocument16 pagesAn International Study of The Impact of B2C Logistics Service Quality On Shopper Satisfaction and LoyaltyKarla Quispe MendezPas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship Marketing An Important Tool For Succe PDFDocument11 pagesRelationship Marketing An Important Tool For Succe PDFSimon Malou Manyang MangethPas encore d'évaluation

- The Analysis of FMCG Product Availability in Retail Stores: February 2015Document9 pagesThe Analysis of FMCG Product Availability in Retail Stores: February 2015andrew garfieldPas encore d'évaluation

- Study On B2B MarketingDocument34 pagesStudy On B2B MarketingNikhila KuchibhotlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Branding of CommoditiesDocument16 pagesBranding of CommoditiesanujpatniPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.1 BackgroundDocument27 pages1.1 BackgroundrahulprajapPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Branding in The Banking IndustryDocument3 pagesRole of Branding in The Banking IndustryAkshita Rajawat0% (1)

- Understanding Key Account ManagementDocument75 pagesUnderstanding Key Account ManagementConnie Alexa D100% (1)

- Full Download Business To Business Marketing 4th Edition Brennan Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesFull Download Business To Business Marketing 4th Edition Brennan Solutions Manualcomnickshay100% (35)

- The Financial Impact of CRM ProgrammesDocument15 pagesThe Financial Impact of CRM ProgrammesPrabhu ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- SegmentationDocument11 pagesSegmentationmridz11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Derivatives: A Question of TrustDocument10 pagesMarketing Derivatives: A Question of Trustram9261891Pas encore d'évaluation

- Adding ValueDocument12 pagesAdding ValueramsankarkmPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing Routes To MarketDocument20 pagesManaging Routes To MarketbugcheckvnPas encore d'évaluation

- Masters ThesisDocument88 pagesMasters ThesisJVD PrasadPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid Term Assignment: Adeel Ahmed Khwaja Salman Shakir Madiha Anwar Waqas Mahmood ChaudryDocument6 pagesMid Term Assignment: Adeel Ahmed Khwaja Salman Shakir Madiha Anwar Waqas Mahmood ChaudryMadiha AnwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Business To Business Marketing OverviewDocument10 pagesBusiness To Business Marketing OverviewJoel ColePas encore d'évaluation

- B2B Services Branding in The Logistics Service IndustryDocument11 pagesB2B Services Branding in The Logistics Service IndustryUttam SatapathyPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Papers On Distribution ChannelsDocument8 pagesResearch Papers On Distribution Channelsihprzlbkf100% (1)

- Comparative Study Tesco and SainsburyDocument66 pagesComparative Study Tesco and SainsburyAdnan Yusufzai100% (1)

- Customer Relationship ManmagementDocument51 pagesCustomer Relationship ManmagementmuneerppPas encore d'évaluation

- b2b Marketing LaurensiaPutriAswanDocument15 pagesb2b Marketing LaurensiaPutriAswanlaronPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Evaluation and Competitive Advantage in Retail Financial Services - A Research AgendaDocument22 pagesConsumer Evaluation and Competitive Advantage in Retail Financial Services - A Research Agendajjle100% (2)

- Customer Relationship ManagementDocument255 pagesCustomer Relationship ManagementRamchandra MurthyPas encore d'évaluation

- 09 Latydhova Syaglova Oyner PDFDocument9 pages09 Latydhova Syaglova Oyner PDFCatherine JeanePas encore d'évaluation

- Pricing Types: Signalling Market Positioning IntentD'EverandPricing Types: Signalling Market Positioning IntentPas encore d'évaluation

- Supply Chain Management Term Paper TopicsDocument5 pagesSupply Chain Management Term Paper Topicsafmzynegjunqfk100% (1)

- Are Product Returns A Necessary Evil? Antecedents and ConsequencesDocument17 pagesAre Product Returns A Necessary Evil? Antecedents and ConsequencesKshitiz GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Conceptualisations of The Consumer in Marketing ThoughtDocument21 pagesConceptualisations of The Consumer in Marketing Thoughtwail iyadPas encore d'évaluation

- Customers Rule! (Review and Analysis of Blackwell and Stephan's Book)D'EverandCustomers Rule! (Review and Analysis of Blackwell and Stephan's Book)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Market Segmentation: How to Do It and How to Profit from ItD'EverandMarket Segmentation: How to Do It and How to Profit from ItPas encore d'évaluation

- The Customer Revolution (Review and Analysis of Seybold's Book)D'EverandThe Customer Revolution (Review and Analysis of Seybold's Book)Pas encore d'évaluation

- An Introduction to Global Supply Chain Management: What Every Manager Needs to UnderstandD'EverandAn Introduction to Global Supply Chain Management: What Every Manager Needs to UnderstandPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Management Worked Assignment: Model Answer SeriesD'EverandMarketing Management Worked Assignment: Model Answer SeriesPas encore d'évaluation

- Walmart Assignment1Document13 pagesWalmart Assignment1kingkammyPas encore d'évaluation

- Math 209: Numerical AnalysisDocument31 pagesMath 209: Numerical AnalysisKish NvsPas encore d'évaluation

- Cap 1 Intro To Business Communication Format NouDocument17 pagesCap 1 Intro To Business Communication Format NouValy ValiPas encore d'évaluation

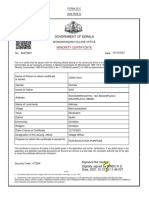

- Government of Kerala: Minority CertificateDocument1 pageGovernment of Kerala: Minority CertificateBI185824125 Personal AccountingPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 12 - Gerund and Infinitive (Task)Document1 pageUnit 12 - Gerund and Infinitive (Task)AguPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Islm WBDocument6 pages2 Islm WBALDIRSPas encore d'évaluation

- Mahabharata Reader Volume 1 - 20062023 - Free SampleDocument107 pagesMahabharata Reader Volume 1 - 20062023 - Free SampleDileep GautamPas encore d'évaluation

- MKTG How Analytics Can Drive Growth in Consumer Packaged Goods Trade PromotionsDocument5 pagesMKTG How Analytics Can Drive Growth in Consumer Packaged Goods Trade PromotionsCultura AnimiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan1 Business EthicsDocument4 pagesLesson Plan1 Business EthicsMonina Villa100% (1)

- Comparative Analysis Betwee Fast Restaurats & Five Star Hotels RestaurantsDocument54 pagesComparative Analysis Betwee Fast Restaurats & Five Star Hotels RestaurantsAman RajputPas encore d'évaluation

- Hyrons College Philippines Inc. Sto. Niño, Tukuran, Zamboanga Del Sur SEC. No.: CN200931518 Tel. No.: 945 - 0158Document5 pagesHyrons College Philippines Inc. Sto. Niño, Tukuran, Zamboanga Del Sur SEC. No.: CN200931518 Tel. No.: 945 - 0158Mashelet Villezas VallePas encore d'évaluation

- Business Intelligence in RetailDocument21 pagesBusiness Intelligence in RetailGaurav Kumar100% (1)

- Basic Statistics For Business AnalyticsDocument15 pagesBasic Statistics For Business AnalyticsNeil Churchill AniñonPas encore d'évaluation

- Accounting For Employee Stock OptionsDocument22 pagesAccounting For Employee Stock OptionsQuant TradingPas encore d'évaluation

- E-Book 4 - Lesson 1 - Literary ApproachesDocument5 pagesE-Book 4 - Lesson 1 - Literary ApproachesreishaunjavierPas encore d'évaluation

- PCA Power StatusDocument10 pagesPCA Power Statussanju_81Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics - FinalsDocument18 pagesEthics - Finalsannie lalangPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Effectively CommunicateDocument44 pagesHow To Effectively CommunicatetaapPas encore d'évaluation

- Esok RPHDocument1 pageEsok RPHAzira RoshanPas encore d'évaluation

- Richards and Wilson Creative TourismDocument15 pagesRichards and Wilson Creative Tourismgrichards1957Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Court of Heaven 1Document2 pagesThe Court of Heaven 1Rhoda Collins100% (7)

- 580 People vs. Verzola, G.R. No. L-35022Document2 pages580 People vs. Verzola, G.R. No. L-35022Jellianne PestanasPas encore d'évaluation

- Glgq1g10 Sci Las Set 4 ColoredDocument4 pagesGlgq1g10 Sci Las Set 4 ColoredPogi AkoPas encore d'évaluation

- GMAT2111 General Mathematics Long Quiz 2Document2 pagesGMAT2111 General Mathematics Long Quiz 2Mike Danielle AdaurePas encore d'évaluation

- Apcr MCR 3Document13 pagesApcr MCR 3metteoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Geoland InProcessingCenterDocument50 pagesGeoland InProcessingCenterjrtnPas encore d'évaluation

- Colour Communication With PSD: Printing The Expected With Process Standard Digital!Document22 pagesColour Communication With PSD: Printing The Expected With Process Standard Digital!bonafide1978Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thermal ComfortDocument6 pagesThermal ComfortHoucem Eddine MechriPas encore d'évaluation