Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Surgical Management of Vascular Lesion in H&N

Transféré par

Dipti Patil0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

109 vues7 pagesVascular anomalies are amongst the most common congenital abnormalities observed in infants and children. Their occurrence in the head and neck region is a source of functional and aesthetic compromise. A new classification based on the anatomical location and depth of the lesion has been proposed.

Description originale:

Titre original

Surgical Management of Vascular Lesion in h&n

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentVascular anomalies are amongst the most common congenital abnormalities observed in infants and children. Their occurrence in the head and neck region is a source of functional and aesthetic compromise. A new classification based on the anatomical location and depth of the lesion has been proposed.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

109 vues7 pagesSurgical Management of Vascular Lesion in H&N

Transféré par

Dipti PatilVascular anomalies are amongst the most common congenital abnormalities observed in infants and children. Their occurrence in the head and neck region is a source of functional and aesthetic compromise. A new classification based on the anatomical location and depth of the lesion has been proposed.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 7

Clinical Paper

Congenital Craniofacial Anomalies

Surgical management of

vascular lesions of the head and

neck: a review of 115 cases

S. C. Nair, N. J. Spencer, K. P. Nayak, K. Balasubramaniam: Surgical management

of vascular lesions of the head and neck: a review of 115 cases. Int. J. Oral

Maxillofac. Surg. 2011; 40: 577583. #2011 International Association of Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgeons. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

S. C. Nair

1

, N. J. Spencer

2

,

K. P. Nayak

3

, K. Balasubramaniam

3

1

Maxillofacial Surgery Department,

Bangalore Institute of Dental Sciences,

Bangalore, India;

2

University of Cincinnatti,

USA;

3

B.M. Jain Hospital, India

Abstract. Vascular anomalies are amongst the most common congenital

abnormalities observed in infants and children. Their occurrence in the head and

neck region is a source of functional and aesthetic compromise. This article reviews

the surgical management of 115 cases of vascular anomalies involving the head and

neck area treated by the authors between 1998 and 2009. It discusses the diagnostic

aids, treatment protocol and the results obtained. A new classication based on the

anatomical location and depth of the lesion has been proposed. This allows

guidelines for surgical ablation of the vascular lesions. The complications

encountered are discussed. The use of external carotid artery control as opposed to

pre-surgical embolization has proved effective and the technique is described. The

location and extent of a vascular malformation should dictate the preoperative

investigations, surgical procedure and subsequent outcome.

Keywords: surgery; head; neck; lesions.

Accepted for publication 3 February 2011

Available online 22 March 2011

Vascular anomalies are a group of lesions

derived fromblood vessels and lymphatics

with widely varying histology and clinical

behaviour. They constitute the most com-

mon congenital abnormalities in infants

and children. James Wardrop, a London

surgeon, rst recognized the differences

between true hemangiomas and the less

common vascular malformations in

1818

14

. Despite Dr. Wardrops work,

descriptive identiers such as Strawberry

hemangioma and salmon patch continued

to be used until the 1980s. This terminol-

ogy did not correlate with the biological

behaviour or histology of these lesions. In

1982, Mulliken and Glowacki greatly

advanced the eld by introducing a

biological classication which differen-

tiated vascular lesions into two distinct

entities: hemangiomas and vascular mal-

formations

13,14

. The term hemangioma

now describes a lesion that is neoplastic,

demonstrating endothelial hyperplasia.

Vascular malformations, conversely, do

not demonstrate cellular hyperplasia but

display progressive ectasia of abnormal

vessels lined by at endothelial on a thin

basal lamina. A more practical classica-

tion integrating their biological behaviour

with dynamics of ow was later advanced

(Table 1)

7

.

The diagnosis of this group of lesions

primarily depends on the history of the

lesion and the clinical presentation. Radio-

graphic evaluation may be helpful in

determining the exact extent, location

and ow dynamics of some lesions.

Patients and methods

One hundred and fteen patients treated

by the authors between 1999 and 2009

were reviewed retrospectively. Relevant

data including gender, age, age at presen-

tation of symptoms, anatomical site of

lesion, relevant radiographic investiga-

tions and period of follow up were tabu-

lated. Exclusion criteria included

segmental lesions and those associated

with syndromes such as Sturge-Weber.

Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011; 40: 577583

doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2011.02.005, available online at http://www.sciencedirect.com

0901-5027/060577 +07 $36.00/0 # 2011 International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

All patients underwent surgery as the

principal modality of treatment. Com-

puted tomography (CT) with contrast,

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and

angiography were used based on the ana-

tomical location and ow dynamics of the

lesion. Selective control of the external

carotid artery to reduce blood ow into the

lesion was used effectively by the author

in lieu of routine preoperative emboliza-

tion.

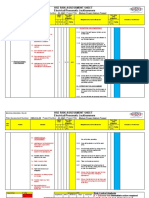

Technique for external carotid control

The external carotid artery (ECA) of the

involved side is exposed through a cervi-

cal incision, which often forms part of the

access for removal of the malformation

(Fig. 1). The sternocleidomastoid muscle

is retracted posteriorly at the level of the

greater cornu of the hyoid bone, exposing

the carotid sheath. The external carotid

distal to the carotid bifurcation is identi-

ed. The vessel is snared with a vascular

sling passed through a red rubber catheter.

Gentle strangulation of the vessel can be

accomplished by advancing the catheter.

This additional compression of the vessel

serves to reduce blood ow to the lesion.

The lesion is exposed with great care taken

not to disturb the vascular network. Feed-

ing arteries and draining vessels are iden-

tied and ligated, permitting total excision

of the lesion. The wound is closed primar-

ily with vacuum drains in situ. The mal-

formations were categorized into ve

types depending on their anatomy and

depth of location in the head and neck

region (Table 2). In type I supercial

lesions requiring excision of skin or

mucosa, local or regional aps have been

used in defect reconstruction (Fig. 2).

Type II submucosal lesions require com-

plete excision after elevation of skin aps

(Fig. 3). Type III lymphovenous malfor-

mations or venous malformations invol-

ving salivary glands are excised along

with the affected gland (Fig. 4). Type

IV intraosseous lesions require excision

with involved bone and reconstruction

when required (Fig. 5). Type V lesions

involving deep visceral spaces, such as the

parapharyngeal or infra-temporal fossa,

require mandibular access osteotomy for

complete exposure and total excision

(Fig. 6). The above classication helped

in determining the surgical approach and

reconstruction necessary for the type of

vascular lesion.

Results

Of the 115 patients evaluated, 63 were

male and 52 female. The youngest patient

was a 2-year-old girl with a lymphatic

malformation in the parotid region (type

III) and the oldest was a 58-year-old male

with a venous malformation involving the

entire tongue and submandibular region

(type II). Table 3 shows the patients cate-

gorized into types with gender distribu-

tion. 38 patients with type I, 44 patients

with type II, 12 patients with type III, 11

patients with type IV and 10 patients with

type V anomalies were treated success-

fully by surgical ablation of their vascular

lesions. Four patients with type I lesions

required reconstruction with local or

regional aps and 2 patients with type

IV lesions required reconstruction of

resected mandible. Only 88 patients could

provide an approximate time of appear-

ance of the lesion. In 27 patients the lesion

had been noticed at birth or soon after. The

remaining 61 patients were clinically

aware of it shortly before their rst surgi-

cal visit. Table 4 highlights the different

imaging techniques used according to the

578 Nair et al.

Table 1. Existing classication of hemangiomas and vascular malformations.

A. Hemangiomas

Supercial (capillary hemangioma)

Deep (cavernous hemangioma)

Compound (capillary cavernous hemangioma)

B. Vascular malformations

Simple lesions

Low-ow lesions

Capillary malformations (capillary hemangioma, port-wine stain)

Venous malformation (cavernous hemangioma)

Lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma, cystic hygroma)

High-ow lesions

Arterial malformation

Combined lesions

Arteriovenous malformations

Lymphovenous malformations

Other combinations

Fig. 1. ECA snared with vascular sling.

Table 2. Categorization of vascular malfor-

mation based on anatomical presentation.

Type I Mucosal/cutaneous (Fig. 2)

Type II Submucosal/subcutaneous (Fig. 3)

Type III Glandular (Fig. 4)

Type IV Intraosseous (Fig. 5)

Type V Deep visceral (Fig. 6)

Table 3. Patients and age according to the

types of the various vascular lesions.

Type Age (years) Female Male

I 744 (24.705)

a

15 23

II 352 (23.27)

a

25 19

III 243 (26.2)

a

7 5

IV 849 (22.8)

a

3 8

V 1856 (32.8)

a

4 6

a

Average age.

type of malformation. At the authors

centre CT scanning with contrast is the

most frequently used imaging modality.

Table 5 demonstrates the method of hae-

morrhage control used for the malforma-

tion. Pre-surgical embolization was

restricted to two patients and external

carotid artery control was required in 52

patients. Complications encountered are

listed in Table 6. One hundred and eleven

patients gained an acceptable aesthetic

outcome with a single procedure. Table

7 summarizes the surgical plan employed

for each type of lesion and the reconstruc-

tion used when required.

Discussion

The rst public demonstration of ether

anaesthesia by William Green Morton in

1846 was for surgical removal of a venous

vascular malformation

14

. Numerous

attempts to understand, classify and treat

these lesions have met with unpredictable

outcomes. The classication proposed by

Mulliken and Glowacki differentiated this

group of lesions into the biologically active

hemangiomas and inactive vascular mal-

formations. Classication led to improved

understanding of the behaviour of these

lesions. Timing of treatment could be based

on a scientic understanding of the lesions

biological behaviour rather than clinical

appearance or the surgeons sense of

gestalt

14

. Subsequently, Mulliken and

Kaban introduced the ow dynamics of

vascular lesions, describing hi-ow and

low-ow vascular malformations

10

. More

recently, a practical classication (Table 1)

has helped to consolidate all previous clas-

sication

7

. The authors have categorized

vascular lesions requiring surgery into ve

types. This simplied categorization pro-

vides input into the investigation and effec-

tive surgical management of various

lesions based on anatomical presentation.

Diagnosis of vascular malformations

depends on precise identication, accurate

history, physical examination and the

proper use of imaging. Advances in ima-

ging have led to the unnecessary exposure

of many lesions. Grey scale ultrasound

and Doppler analysis are useful in dening

whether the lesion is solid or cystic and in

establishing the ow dynamics of a

lesion

17

. In evaluating vascular malforma-

tions, MRI has a major advantage over CT

or angiography in differentiating heman-

giomas from the surrounding structures,

but its cost and limited availability can be

prohibitive to its use. In the authors

experience, imaging is restricted to CT

with contrast for most lesions for cost

reasons. MRI is restricted to 2 patients

Surgery for vascular head and neck lesions 579

Fig. 2. Type I low ow cutaneous venous malformation.

Fig. 3. Type II low ow vascular malformation in the buccal region.

Table 4. Imaging techniques used in the different types of vascular lesion.

Type I

n = 38

Type II

n = 44

Type III

n = 12

Type IV

n = 11

Type V

n = 10

CTC 32 34 7 2 6

MRI 0 1 1 0 0

Angiogram 0 5 4 8 4

No investigation 6 4 0 1 0

and angiography to 18 patients (Table 4).

Angiography, particularly digital subtrac-

tion angiography (Fig. 7), has a specic but

limited role in the diagnosis of vascular

lesions. It is restricted to lesions requiring

therapeutic endovascular intervention

7

.

Selective embolization as a single treat-

ment modality is rarely successful with

high owanomalies because of rapid estab-

lishment of newpathways of ow. Ligation

of main feeder vessels is also forbidden due

to low success rates and its elimination of

access for future embolization

3,5,12,16

.

The use of temporary control (ligation)

of the ECA instead of presurgical embo-

lization has proven effective in reduction

of blood ow to the lesion, allowing effec-

tive excision with minimal blood loss.

Where blood replacement is required,

autologous transfusion is preferred. When

embolization is chosen subsequent to digi-

tal subtraction angiograph (DSA) it should

proceed from distal to proximal thus ablat-

ing both the nidus and its source

18

. Choice

of embolic agents is purely the clinicians

preference. Gelfoam, polyvinyl alcohol,

silicone uid and isobutyl-2 cyanoacrylate

are commonly used agents

7

. When embo-

lization is used, surgery is carried out

within 2448 h to prevent the develop-

ment of collateral blood supply

1,4,6,9,11

.

The use of presurgical embolization was

restricted to two patients with type V

(deep visceral) lesions, both of which

required ECA control intraoperatively

despite embolization. One of these

patients presented for surgical manage-

ment after undergoing an emergent embo-

lization. The second presented with both

ECAs feeding into the lesion; one was

embolized and the other controlled with

temporary intraoperative ligation.

Sclerotherapy has a promising but lim-

ited role in the management of vascular

lesions. Success has been realized in the

treatment of macrocystic lesions. The ther-

apy has been less effective in treating

microcystic vascular malformations

2,8,15

.

The different agents used include sodium

tetradecyl sulphate (3%), sodiumtetradecyl

acetate and more recently OK 432 (lyophi-

lized Streptococcus pyogenes treated with

benzyl penicillin)

7

.

Surgery has been used effectively to

eradicate or minimize the lesion in this

review of 115 cases. Surgery must be

aimed at removal of the entire nidus along

with any structure associated with the

lesion because any remaining vasculature

will probably lead to recurrence. The pro-

posed classication (Table 2) was used to

help plan the approach and extent of

resection. Supercial lesions required

excision of skin or mucosa with recon-

580 Nair et al.

Fig. 4. (a) Type III lymphovenous malformation in left parotid gland. (b) Exposure of lesion

through preauricular incision with cervical extension. (c) Excised specimen showing cystic

spaces. (d) 2-Month postoperative appearance after total excision of lesion with gland.

Fig. 5. Type IV intra bony hi-ow arterial malformation in maxilla.

struction using local or regional aps.

Lesions involving the parotid or subman-

dibular gland require excision of the gland

with preservation of nerves. Deeper

lesions necessitate access osteotomies

for excision. Lesions within bone, under-

went bone resection followed with recon-

struction using autologous grafts. In one

patient with arteriovenous malformation

(AVM) in the mandible, successful repla-

cement of the resected mandible after

enucleation of the pathology was per-

formed. Skeletal deformities secondary

to lymphangiomas were common and

required secondary correction of the ske-

letal deformity. Table 7 demonstrates the

authors surgical approach to vascular

malformations based on anatomical pre-

sentation. The complications were

restricted to morbidity with no mortality.

The most common problem encountered

was incomplete excision requiring another

operation at a later date. Temporary par-

esis of branches of facial nerve and exces-

sive intraoperative haemorrhage were also

seen. Excessive haemorrhage was dened

as blood loss requiring more than auto-

logous transfusion. The overall satisfac-

tion quotient was high.

In conclusion, the use of intraoperative

control of branches of the external carotid

artery has proved a successful, safe and

effective method of intraoperative hae-

morrhage control when removing these

potentially bloody lesions. The approach

is easy to incorporate into the access

necessary to remove the lesion. An

increase in morbidity by this approach

was not seen compared with lesions trea-

ted with preoperative embolization. The

present accepted classication (Table 1)

attempts to correlate the biological classi-

cation by Mulliken and Glowacki with

the ow dynamics of the lesion. Whilst

Surgery for vascular head and neck lesions 581

Fig. 6. Type V MRI showing venous malformation in lateral and post-pharyngeal space.

Table 5. Number of patients who had ECA control as against pre-surgical embolization.

Type I

n = 38

Type II

n = 44

Type III

n = 12

Type IV

n = 11

Type V

n = 10

ECA control 1 32 11 11 10

Non-ECA control 37 12 1 Nil Nil

Embolization Nil Nil Nil 1

a

1

a

a

Had ECA control along with presurgical embolization.

Table 6. Complications encountered in the different types of vascular anomalies with the site and prescribed imaging modality.

SL Classication Age Sex Site Investigation Complication

1 Type IV 8 M Lt maxilla Angio Excessive intraoperative haemorrhage

2 Type II 23 F Rt cheek Angio Incomplete excision

3 Type IV 8 M Lt maxilla Angio with presurgical

embolization

Recurrence in mandible

4 Type I 19 F Lt upper lip CTC Overexcision with hypoplastic apearance

5 Type II 31 F Rt cheek CTC Temporary neuroparesis VII nerve

6 Type I 25 F Tongue CTC Residual lesion cheek

7 Type I 22 F Lower lip CTC Incomplete excision and scarring

8 Type II 21 F Lt lower eyelid CTC Temporary ectropion

9 Type V 18 F Lt infra temporal fossa Angio with presurgical

embolization

VII nerve weakness

10 Type V 23 M Lt temporal fossa CTC Intraoperative haemorrhage from cavernous sinus

Table 7. Surgical treatment advocated for the types of vascular anomalies.

Classication Male Female Treatment

Type I Mucosal/cutaneous lesion arising from

papillary dermis involving skin or mucosa (n = 38)

23 15 Excision with overlying skin or mucosa

Primary closure or regional ap

Type II Submucosal or subcutaneous with no discoloration

of overlying skin (n = 44)

19 25 Surgical access to lesion with total excision and primary

closure

Type III Lesions involving glands ex-parotid/

submandibular (n = 12)

5 7 Surgical access to glandular lesions with excision along

with the involved gland and primary closure (Fig. 4AD)

Type IV Skeletal involving the facial skeleton

ex-maxilla/mandible/zygoma (n = 11)

8 3 Excision of involved skeletal structure with reconstruction

Type V Deep visceral ex-parapharyngeal/

infratemporal (n = 10)

6 4 Mandibulotomy to access the lesion followed by total excision

this is helpful in understanding the lesions

behaviour, a further categorization of

lesions that require operative intervention

based on the technique needed for surgical

treatment would be helpful to the managing

surgeon. The authors describe a simplied

algorithmfor effective management of vas-

cular lesions requiring surgery (Table 7).

For example, hemangiomas are treated

with a wait and watch policy since they

frequently undergo resolution, but vascular

malformations causing functional or aes-

thetic deformity are dealt with at the earliest

opportunity. Proper management depends

not only on the biological behaviour, but

also on site of anatomical presentation.

Presentation of a lesion not only as a venous

malformation, but as a type V venous mal-

formation gives the surgeon the additional

information needed to plan treatment prop-

erly. Adequate imaging techniques are the

key to the successful diagnosis and effec-

tive treatment of all vascular anomalies.

Angiography should be restricted to

anomalies requiringendovascular interven-

tion and lesions that may have feeders from

the internal carotid artery. MRI with fat

suppressed images is most effective. The

use of alternative therapy, such as emboli-

zation and sclerotherapy, has an effective

but limited role in treating vascular lesions.

The use of clinical data with non-invasive

imaging techniques, followed by precise

surgery has been successful in providing

satisfactory treatment in the majority of

patients. Segmental and large composite

lesions require multiple therapies. Eradica-

tion is unlikely with either surgery alone or

combination therapies.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Retrospective case review ethical clear-

ance not required.

Acknowledgements. Prof. Paul Stoelinga,

Nijmegen, Netherlands and Dr. Deepak

Gopalakrishnan, University of Cincin-

natti, USA are acknowledged for their

support in preparing this manuscript.

References

1. Azzzolini A, Bertani A, Riberti C.

Superselective embolization and immedi-

ate surgical treatment; our present

approach to treatment of vascular heman-

giomas of the face. Ann Plast Surg 1982:

9: 4260.

2. Baneieghlal B, Davis MR. Guidelines

for the successful treatment of lymphna-

gioma with OK-432. Eur J Pediatr Surg

2003: 13: 103107.

3. Biller HF, Krespi YP, Som PM. Com-

bined therapy for vascular lesions of the

head and neck with intra-arterial emboli-

zation and surgical excision. Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg 1982: 90: 37.

4. Burrows PE, Lasjaunias PL, Ter

Brugge KG, Flodmark O. Urgent and

emergent embolisation of lesions of head

and neck in children: indications and

results. Pediatrics 1987: 80: 386394.

5. Demuth RJ, Milller SH, Kellar F.

Complications of embolization treatment

for problem cavernous hemangiomas.

Ann Plast Surg 1984: 13: 135144 6.

6. Emjolras O, Logeart I, Gelbert F,

Lemarchand-Venencie F, Reizihne

D, Guichard JP, Merland JJ. Arterio

venous malfomations: a study of 200

cases. Ann Dermatol Venerol 2000:

127: 1722.

7. Ethunandan M, Mellor TK. Heman-

giomas and vascular malformations of the

maxillofacial region review. Br J Max-

illofac Surg 2006: 44: 263272.

8. Giguere CM, Bauman NM, Sata Y,

Burke DK, Grienwald JH, Pransky

S, Kelley P, Georgeson K, Smith

RJ. Treatment of lymphangiomas with

OK-432(Picibani) sclerotherapy: a pro-

spective multiinstitutional trial. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002:

128: 11371144.

9. Jackson IT, Carreno R, Potparic Z,

Hussain K. Hemangiomas, vascular mal-

formation, and lymphovenous malforma-

tions: classication and methods of

treatment. Plast Recontr Surg 1993: 91:

12161230.

10. Kaban LB, Mulliken JB. Vascular

anomalies of maxillofacial region. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 1986: 44: 203213.

11. Kahout MP, Hansen M, Pribaz JJ,

Mulliken JB. Arterio venous malforma-

tions of the head and neck: natural history

582 Nair et al.

Fig. 7. Digital subtraction angiography of submandibular hi-ow AVM.

and management. Plast Reconstr Surg

1998: 102: 643654.

12. Merland JJ, Riche MC, Hadjean E.

The use of superselective arteriography,

embolization and surgery in the current

management of cervicocephalic vascular

malformations (350 cases). In: Williams

HB, ed: Symposium on Vascular Malfor-

mation and Melanotic LesionsSt Louis,

Mosby, 1983.

13. Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangio-

mas and vascular malformations in

infants and children: a classication

based on endothelial characteristrics.

Plast Reconstr Surg 1982: 69: 412422.

14. Mulliken JB, Young AE. Vascular

birthmarks. Hemangiomas and Malfor-

mations. Philadelphia: Saunders 1988.

15. Ogita S, Tsuto T, Nakamura K, Degu-

chi E, Iwai N. OK-432 therapy in 64

patients with lymhangioma. J Pediatr

Surg 1994: 29: 784785.

16. Persky MS. Congenital vascular lesions

of the head and neck. Laryngoscope

1986: 96: 1002.

17. Platiel HJ, Burrows PE, Kozakewich

HPW, Zurakowski D, Mulliken JB.

Soft tissue vascular anomalies: utility of

US for diagnosis. Radiology 2002: 214:

747754.

18. Waner M, Suen JY. Hemangiomas and

Vascular Malformations of the Head and

Neck. New York: Wiley-Liss 1999:.

Address:

Sanjiv C. Nair

Maxillofacial Surgery

Bangalore Institute of Dental Sciences

Wilson Garden

Bangalore 560 029

India

Tel.: +91 98454 33106

E-mail: snmaxfax@gmail.com

Surgery for vascular head and neck lesions 583

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- SHCO Second Edition - NEDocument65 pagesSHCO Second Edition - NESwati Bajpai100% (2)

- Milton Terry Biblical HermeneuticsDocument787 pagesMilton Terry Biblical HermeneuticsFlorian100% (3)

- Business Research Chapter 1Document27 pagesBusiness Research Chapter 1Toto H. Ali100% (2)

- Factoring Problems-SolutionsDocument11 pagesFactoring Problems-SolutionsChinmayee ChoudhuryPas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure of El Cimarron by HenzeDocument2 pagesBrochure of El Cimarron by HenzeLuigi AttademoPas encore d'évaluation

- LEGO Group A Strategic and Valuation AnalysisDocument85 pagesLEGO Group A Strategic and Valuation AnalysisRudmila Ahmed50% (2)

- Small Healthcare Organization: National Accreditation Board For Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (Nabh)Document20 pagesSmall Healthcare Organization: National Accreditation Board For Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (Nabh)Dipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)Document11 pagesEnhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)Dipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- 5th Edition Hospital STD April 2020 PDFDocument148 pages5th Edition Hospital STD April 2020 PDFFeroz Ikbal100% (1)

- Aneurysmal Bone CystDocument5 pagesAneurysmal Bone CystDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- 0PIOIDDocument77 pages0PIOIDDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- ChandraDocument17 pagesChandraDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Adverse Effect of Chemotherapy.Document3 pagesAdverse Effect of Chemotherapy.Dipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Cerebral Shunts: DR Dipti Patil (1 MDS) Dept of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery KCDS, BangloreDocument25 pagesCerebral Shunts: DR Dipti Patil (1 MDS) Dept of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery KCDS, BangloreDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Harish: Odontogenic Kerato CystDocument4 pagesHarish: Odontogenic Kerato CystDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- New Findings and Controversies in Odontogenic TumorsDocument4 pagesNew Findings and Controversies in Odontogenic TumorsDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Additives To Local Anesthetics For PeripheralDocument1 page1 Additives To Local Anesthetics For PeripheralDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Intravenous Lipid Emulsion As Antidote For Local ADocument1 pageIntravenous Lipid Emulsion As Antidote For Local ADipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Clotting FactorDocument2 pagesClotting FactorDipti Patil100% (1)

- Forehead Flap: DR Dipti Patil (1 MDS) Dept of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery KCDS, BangloreDocument42 pagesForehead Flap: DR Dipti Patil (1 MDS) Dept of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery KCDS, BangloreDipti PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Secretary: A. Duties and TasksDocument3 pagesMedical Secretary: A. Duties and TasksNoona PlaysPas encore d'évaluation

- Houses WorksheetDocument3 pagesHouses WorksheetYeferzon Clavijo GilPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading 7.1, "Measuring and Managing For Team Performance: Emerging Principles From Complex Environments"Document2 pagesReading 7.1, "Measuring and Managing For Team Performance: Emerging Principles From Complex Environments"Sunny AroraPas encore d'évaluation

- 4TES-9Y 20KW With InverterDocument4 pages4TES-9Y 20KW With InverterPreeti gulatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Omnibus Motion (Motion To Re-Open, Admit Answer and Delist: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesOmnibus Motion (Motion To Re-Open, Admit Answer and Delist: Republic of The PhilippinesHIBA INTL. INC.Pas encore d'évaluation

- W1 MusicDocument5 pagesW1 MusicHERSHEY SAMSONPas encore d'évaluation

- Poetry Analysis The HighwaymanDocument7 pagesPoetry Analysis The Highwaymanapi-257262131Pas encore d'évaluation

- Body ImageDocument7 pagesBody ImageCristie MtzPas encore d'évaluation

- Your Song.Document10 pagesYour Song.Nelson MataPas encore d'évaluation

- Four Year Plan DzenitaDocument4 pagesFour Year Plan Dzenitaapi-299201014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bruce and The Spider: Grade 5 Reading Comprehension WorksheetDocument4 pagesBruce and The Spider: Grade 5 Reading Comprehension WorksheetLenly TasicoPas encore d'évaluation

- SwimmingDocument19 pagesSwimmingCheaPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 Electrical Jack HammerDocument3 pages9 Electrical Jack HammersizwePas encore d'évaluation

- HDFCDocument60 pagesHDFCPukhraj GehlotPas encore d'évaluation

- Electronic Form Only: Part 1. Information About YouDocument7 pagesElectronic Form Only: Part 1. Information About YourileyPas encore d'évaluation

- Gmail - Payment Received From Cnautotool - Com (Order No - Cnautot2020062813795)Document2 pagesGmail - Payment Received From Cnautotool - Com (Order No - Cnautot2020062813795)Luis Gustavo Escobar MachadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Abb PB - Power-En - e PDFDocument16 pagesAbb PB - Power-En - e PDFsontungPas encore d'évaluation

- Connecting Microsoft Teams Direct Routing Using AudioCodes Mediant Virtual Edition (VE) and Avaya Aura v8.0Document173 pagesConnecting Microsoft Teams Direct Routing Using AudioCodes Mediant Virtual Edition (VE) and Avaya Aura v8.0erikaPas encore d'évaluation

- AllisonDocument3 pagesAllisonKenneth RojoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - (Accounting For Foreign Currency Transaction)Document25 pages2 - (Accounting For Foreign Currency Transaction)Stephiel SumpPas encore d'évaluation

- COPARDocument21 pagesCOPARLloyd Rafael EstabilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Clasificacion SpicerDocument2 pagesClasificacion SpicerJoseCorreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Meter BaseDocument6 pagesMeter BaseCastor JavierPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic of The Philippines Legal Education BoardDocument25 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Legal Education BoardPam NolascoPas encore d'évaluation

- Coffee in 2018 The New Era of Coffee EverywhereDocument55 pagesCoffee in 2018 The New Era of Coffee Everywherec3memoPas encore d'évaluation