Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

AJSS Manora

Transféré par

Alexander HorstmannDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

AJSS Manora

Transféré par

Alexander HorstmannDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

brill.nl/ajss

The Revitalisation and Reexive Transformation of the Manooraa Rongkruu Performance and Ritual in Southern Thailand: Articulations with Modernity

Alexander Horstmann

Max-Planck-Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity

Abstract In this article, I consider the changing forms of a traditional art genre and ritual cycle, Manooraa Rongkruu, in which it is possible for the living to communicate with the dead. I did eldwork on the dynamics of Theravada Buddhism, Islam and indigenous religion and multi-religious rituals in Southern Thailand from 20042007. Religious forms in Southern Thailand have been hybridised, fragmented, post-modernised and revitalised. The performance and art genre of the Manooraa enjoy high popularity in certain parts of Southern Thailand and is used to heal a number of modern ailments. The public performances in Takae, Patthalung and Ta Kura, Songkhla, attract hundreds of thousands of worshippers. I show that the revitalised and reexive religious practices of people in Southern Thailand to engage and worship the great ancestor spirits represent a multi-vocal arena, in which social transformations and discursive shifts are negotiated. Illustrations of the new performances of the Manooraa Rongkruu are provided to illustrate a ritual in movement that negotiates traditional obligations and postmodern requirements. Keywords Southern Thailand, ancestor spirits, Islam, Theravada Buddhism, revitalisation of tradition, social aspirations

Introduction Manooraa Rongkruu is an example how art creates a space that reaches from the world of the living to the realm of the dead.1 The essence of this possession ritual lies in the performance of designated spirit-mediums or even members of the community who become possessed by the ancestral spirits. This allows the living to remember loved ones they have lost, talk to the dead and recollect memories in communitas (Hemmet 1992; Parichat, 2006; Phittaya, 1992,

1 The short form of Manooraa in the Southern Thai dialect is Noora. I use Manooraa throughout for clarity.

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009

DOI: 10.1163/156848409X12526657425307

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

919

2003; Thienchai, 1999, 2003). In this article, I use this chief performance tradition to illustrate the revitalization and reexive transformation of local religion in Southern Thailand. While local intellectuals complain about the commodication and possible corruption of the Manooraa Rongkruu, I show that the creative articulation with the conditions of post-modernity is the foundation of its current revitalisation and its capacity to respond to new needs, identities and social aspirations. Whereas the Manooraa Rongkruu in the past used to incorporate ancestral beliefs, Theravada Buddhism and Islam, I argue that the recongured manifestation is thoroughly associated with the Thai state, Theravada Buddhism and modern aspirations.

Thai Popular Religion The picture of religion in Thailand today is characterised by a contradictory move: while conventional Theravada Buddhism seems to have lost much appeal with the younger generation, Buddhism is also being revived in new forms. The worship of Buddhist saints, the booming cult of Buddhist amulets, and the presence of magic monks show that Buddhism is far from being replaced by secularisation (Jackson, 1999a; Pattana, 2002; Taylor, 1999). The expansion of the capitalist market economy in Thailand has resulted in a deeply polarised society and in a widening gap between the poor and the very rich. Religious forms are no essential phenomena, but have reacted with exibility to the conditions of dislocation, rapid social change and social uncertainty and developed niches in the religious market and religious forms, catering to the poor, the lower middle-class and also to the very wealthy (Guelden, 2007 [1995]; Morris, 2000). Buddhism is also fragmented: Taylor argues that it has been commodied (Taylor, 1999). In Bangkok, for example, some of the temples have become like shopping centres in which wealthy patrons donate lavishly to the Sangha for Kathin or funeral ceremonies. Buddhism also becomes revitalised in new Buddhist movements where it appeals closer to the aspirations of the middleclasses: while the capitalist economy and the growing nation-state weakened ancestral traditions and traditional authority in the village, the same forces propelled the dramatic expansion, presence and visibility of spirit-mediums in urban areas (Morris, 2000; Pattana, 2005b; Tanabe, 2002). These urban spiritmediums co-exist and hybridise with revitalised and fragmented Theravada Buddhism. In the parade of deities, the Lord Buddha is regarded as the most respected spirit by spirit-mediums (Pattana, 2005a). Recent research shows that spirit-mediums enjoy huge popularity in contemporary Thailand (Pattana, 2002). It is the thesis of this chapter that the

920

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

growth in spirit-mediums is a reection of social, political and economic changes in Thailand and that religious practices of participation in spirit cults respond creatively to the social transformation of everyday life. The phenomenon is spread throughout the country and the rst studies emerged in southern Thailand (Cohen, 2001; Golomb, 1978, 1985; Guelden, 2005, 2007 [1995]).2 Regional dierences in mediumship reect the ethnic and religious composition and cultural diversity of the South. The manifestations of mediumship include Thai Buddhist, Malay Muslim and Chinese mediums which are possessed by dierent classes of spirits. The issues brought to mediums concern adultery, nancial problems, and various ailments that might be caused by black magic. Despite the existence of numerous clinics and hospitals in the South, healing of physical ailments, including chronic health problems, are still a major issue brought to mediums in parallel to mental problems (Golomb, 1985). Such ailments are also the triggers that urge people to host a Manooraa Rongkruu performance.

Theoretical Developments Bruce Knaufts idea of an articulatory space of the alternatively modern seems to be particularly apt to describe this adaptation of the local script to global economies (see Knauft, 2002). Knauft suggests that alternative modernities happen in a multi-vocal arena that is delimited and framed by local cultural and subjective dispositions on one side, and by global political economies (and their possibilities and limitations) on the other. This perspective has also been used by scholars of Thai religion. J. L. Taylor is among the rst scholars to speak about the hybridisation of Thai Buddhism (Taylor, 1999). Hybridisation means a temporal moment and site of contestation for spiritual meanings and relevance. Taylor argues that the rise of the neo-Buddhist movement Thammakai is a response to the wider forces of globalisation that have profound ramications for Thai social life. Besides hybridity, the postmodernist lens has been used by scholars to refer to current developments in Thai religion that have already seemed to have passed the modern stage. Peter Jackson argues that, The modern phase in Thai religion refers to following a path of doctrinal rationalisation accompanied by organisational centralisation and bureaucratisation whereas the postmodern one is characterised by a resurgence of supernaturalism and an eorescence of

2 I want to highlight the research of Marlane Guelden which is also sensitive to processes of feminisation of the Manoora and the presence and visibility of women in house-based spiritmedium shrines.

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

921

religious expression at the margins of state control, involving a decentralisation and localisation of religious authority. In other words, religion can become a commodity, political ideology, marker of identity, marketing machine or object of worship (Jackson, 1999b). In Manooraa Rongkruu performances, the actors and dancers using local semiotics show the local meaning of what it means to be modern. The Manooraa Rongkruu engages playfully with modernity and integrates modern techniques and commodities in their performance using modern keyboards, microphones, integrating the vastly popular country-song art genre Luuk tung, TV soap operas (lakhon), comments on sexuality, and jokes on politics. The Manooraa troupe becomes an economic enterprise that advertises its services. The Manooraa troupe of Sompong from Ban Takae, for example, owns a eet of ve trucks packed with props for the stage, costumes and crowns.3 The female Nai Manooraa in Tamot who organises a Manooraa dance school also operates a modern video-game hall to make a living. In many ways, the local art form Manooraa represents Knaufts articulatory space in which local belief and cosmology articulates with global culture and where customary production and exchange meets capitalism. The Manooraa performer today has to balance traditional beliefs, values and obligations and modern needs, aspirations and expectations. He is both a shaman and modern entertainer.

What is Manooraa? The Manooraa Rongkruu is a performance genre in which the ancestor spirits are entertained by music and dance and invited to come down to communicate with the living. The ancestor spirits are elevated to the status of teachers and healers. By singing the Manooraa verses, the Manooraa master and medium is able to mobilise the power of healing and knowledge (kruumor) and to transmit it to the designated mediums which become possessed by the spirits of the great Manooraa teachers. The Manooraa Rongkruu illustrates the vitality of popular religion and the spirit world, in tandem with the fragmentation of Theravada Buddhism and Islamic revivalisms in southern Thailand (see Horstmann, 2004). People in Southern Thailand feel they are part of an imagined community, as they are all considered descendents of the rst Manooraa teachers. People and houses, and sometimes whole villages, are considered of Manooraa descent (trakun Manooraa). People are trakun Manooraa because their ancestors were.

3

My own observation.

922

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

Aliation with the Manooraa is, thus, transferred from parents to their children (Gesick, 1995:67).

State of the Art The study of the Manooraa Rongkruu is characterised by an ideal perspective on its cosmological aspects. The perspective which I want to call folkloric does not consider the rapid transformation of the Manooraa Rongkruu and its reexive response to the conditions of modernity. Its focus on the ritual frame presents a picture of an unchanging ritual. This perspective is ahistorical because it ignores the adjustments that the ritual has made in relation to the external forces that impinge on the lives of the people in southern Thailand. This static approach has to do with the motivation of the researcher to provide an authentic picture of the ritual, and regards new elements of the Manooraa as unauthentic or corrupt. Unfortunately, the perpetuation of the traditional image of the Manooraa makes it problematic to understand its changing form. The Manooraa Rongkruu has always responded to the specic conditions of the time and has accommodated the specic interests and power constellations of specic local settings through history. Secondly, I think that previous studies have completely ignored the question of class. The Manooraa Rongkruu of today, the boundary of the rural and urban is withering away and meritmaking and religious practice in Thailand has a fundamental class dimension (Bowie, 1998).4

The Current State of the Manooraa in Southern Thailand Costume, movement and oerings of the Manooraa have not changed and the conventions are the same as a hundred years ago. The Manooraa Rongkruu is fundamentally an exchange between the living and the spirits. On the other hand, the Manooraa hybridises with modernity in a way that allows the mobile middle-class to express its aspirations of fortune. The performance of a Manooraa Rongkruu is being used to establish ones benefactor status in society or it is being used to exhibit ones power and prestige. By far the most encompassing meaning of the Manooraa Rongkruu is healing. In modern times, the Manooraa Rongruu is one of the most ecient remedies for modern illness:

The class dimension of merit-making is brought out clearly in Katherine Bowies work (see Bowie, 1998).

4

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

923

depression, nervous breakdowns, disputes or clashes within the family, personal crises. In this, the Manooraa Rongkruu keeps the traditional function: it is essentially a vow ritual. However, the therapy concerns the maladjustment to modern times. The performance in Takae keeps the form of the Manooraa Rongkruu but it is a much bigger event. The basic meaning of the performance in Takae is similar to the performance in the village though. The performance in Takae is a prosperity ritual; the sponsors and participants hope to excel in business: if the powerful ancestor spirits come down and are prepared to consult with the living, and if the host has been generous, he will be reimbursed with fortune, health and incredible wealth. The dierence is that the traditional ritual remains limited to the kinship group, while the events in Takae equate to a pilgrimage. The travel and participation in Takae is a sacred journey that is regularly undertaken by some pilgrims. The pilgrims hope to merge with the power and charisma of the rst teacher of Manooraa and the tutelary spirit of southern Thailand, Si Sata. The meaning of the ritual is the same; only the size diers. Buddhism in southern Thailand was always indigenised in order to become accepted by the rural population. Buddhist rituals in southern Thailand incorporated ancestral spirit beliefs, whereby the spirits were subordinated to the authority of the Buddha. In the post-modern era, new forms of Buddhism have emerged that hybridise with spirit cults and magic. In southern Thailand, the Manooraa Rongkruu was always associated with Buddhism. The Manooraa teacher usually performs an ordination ceremony and spends some time in the temple. The best Manooraa teachers were allowed to perform in the oldest and most recognised temples and a regular competition was held in Wat Kian in Bang Geow, in Patthalung province. The Manooraa always depended on the patronage by wealthy local elites, the Buddhist Sangha and the nation-state. Yet, it would be erroneous to call the Manooraa a Buddhist ritual. The Manooraa Rongkruu is a multi-religious ritual, in which both Buddhism and Islam were integrated. When I talked to a Manooraa master, shadow-puppet master and national artist who performed for the royal family, he said that the power of Manooraa depends on the sincerity of the heart only. For people who have performed a vow, it is obligatory to invite a Manooraa troupe. Manooraa is about the relationship between the people and spirits. The religious aliation, Buddhist or Muslim, is secondary. The Songkhla Lake area, the heart of Manooraa, came under the inuence of competing Thai and Malay mandala, whereby the Siamese quickly gained the upper-hand. Hence, Theravada Buddhism was installed in southern Thailand. The chronicles of southern Thai townships show that local society was concerned about coming under growing control by the centre in the North

924

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

and that ethnic or religious aliation was not as important as a marker of cultural distinction as it is today (cf. Gesick, 1995). It is dicult to speculate, but from the biography of famous Manooraa teachers, we can assume that the Manooraa came under the increasing inuence of the nation-state and the Buddhist Sangha. In the 1930s, the Manooraa Rongkruu was instrumentalised for government purposes by using famous Manooraa teachers for government propaganda. Manooraa teachers were invited to teach in public colleges. The introduction of new forms of patronage strengthened the morale and prestige of the Manooraa genre. Manooraa teachers showed that they were able to incorporate a politisation of the Manooraa and to mediate between the government and the villagers. As media in the countryside were rare, the Manooraa troupes that travelled the countryside became, themselves, mediators who transmitted the latest news to the population. Although Manooraa troupes fell under new forms of government patronage, the Manooraa troupes were able to keep much of their autonomy. Sometimes, sketches were used to comment on the politics and to joke about certain politicians. In the last decades, the expansion of markets did not leave the Manooraa genre untouched. The market economy poured new energy into the Manooraa and, in turn, provided the means to keep modernity spirited. As Manooraa troupes depended on the market, Manooraa teachers became religious entrepreneurs and their troupe religious enterprises. Manooraa Rongkruu became a religious commodity and one that was eagerly demanded. The troupes that used to travel the countryside now were hired for their performance. It was no longer enough to provide food and drink, but the performance, including the teacher, the dancers and musicians had to be paid. In addition, Manooraa troupes were now hired for public performances in old Buddhist monasteries, such as Wat Kian, Wat Takae and Wat Takura. The troupes began to specialise and occupy specic segments in the market. It was more important then ever to be famous and to have a great reputation. The Manooraa now operated within the booming consumer culture and adjusted once more to current economic realities. A Manooraa teacher in his house showed me his calendar which is fully booked. His troupe meets regularly in his house to prepare the next performance. He performs throughout the region, including in the urban area of Songkhla. The Manooraa Rongkruu is not a rural romantic phenomenon anymore, but has moved into the city. This Manooraa teacher lives in a row-house in a suburban area of Songkhla. His urban connection does not make him less authentic in the eyes of his audience. What counts is his communication with the power of the ancestor spirits.

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

925

The absence of invited Muslim relatives in one Manooraa Rongkruu ceremony of a Chinese-Thai family which I observed in Tamot, Pattalung, illustrates the exhaustion of the integrative potential of the Manooraa. The Islamic ancestor spirit did enter and possess the Buddhist medium which was dressed in Islamic clothes, because no Islamic medium was available. The Manooraa Rongkruu is strongly identied with the Buddhist temple, and the reformist Islamic discourse widespread in the Muslim communities resents the Hindu and Buddhist elements of the ceremony. However, the revived Manooraa Rongkruu tradition in the Songkhla Lake area seems to be losing its Islamic component, which was always weaker than the Buddhist one. While the belief in the power of the ancestors has not withered away in the Muslim communities, the Manooraa Rongkruu ceremonies of the present are largely catered to Buddhists. That does not mean that the Manooraa Rongkruu is a Buddhist tradition, but rather it is a hybridised ceremony integrating myth, history, performing arts, belief and ritual practice. The absence of Muslims in the Manooraa ceremony conrms the transformation of plural spaces into a type of mere co-existence, in which the ritual spaces of Buddhists and Muslims are increasingly separated. The Manooraa is, thus, no longer able to bring all family members together and there are other dimensions than communitas that motivate host families to book a full Manooraa Rongkruu ceremony. Performances of the Manooraa Rongkruu in the Songkhla Lake Region Today In the following, I provide sketches of the new performances of the Manooraa Rongkruu as I observed them in my eldwork to bring out the new articulations of the Manooraa Rongkruu with the forces of modernity. The Manooraa Rongkruu in Ban Dhammakhot, Songkhla Ban Dammakot, where I observed three consecutive Manooraa Rongkruu ceremonies in the household of Wandi and Leg, is exemplary for villages in rural Thailand. Here, many villagers have to leave the village to make a living. There is simply not enough land to feed everyone. The village is not far from the district centre and the main road. Away from their ancestral land, they are not protected by the benevolent spirits and are, thus, vulnerable to the uctuations of the market. The village is named after the Buddhist temple. Not far from Ban Thammakhot, there are Muslim villages near the Lake. The Muslim villages are much poorer than the Buddhist village. Wandi and her husband

926

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

Leg made a small fortune by making cakes and selling them to wholesalers in Hatyai. Thus, the status of Wandi and Leg rose to new rich and they employed many households in their business. However, the business was not stable and the income highly uctuating. In addition, Wandi became ill. She became depressed, anti-social and less lively. She felt unwell. Wandi and Leg dedicate a room to the ancestors. In the garden, they keep a spirit house, where the guardian spirits of the land live. They give regular oerings to the spirits. Wandi and Leg have held Manooraa Rongkruu for three consecutive years. They believe that they should hold a Manooraa every year to have their business be protected by the spirits. The Nai Noora promised that their generosity towards the spirits will be recompensed by increased wealth. Wandi and Leg hired a highly-reputed Manooraa troupe from Songkhla, and they prepared the food and oerings a month in advance. The oerings were presented on great silver plates and included elaborate and accurately presented dishes. In addition, the hosts prepared owers, fresh fruit and more platters. The oerings included both Buddhist and Muslim items presented on dierent shrines in the rong. The performance was opened by ve monks and hardly any Muslims participated. The Buddhist spirit-medium was possessed by the Muslim ancestor spirit. Relatives arrived from many directions and gave donations to help cover the cost of the ritual. In addition to the rich oerings, the food for the guests was plentiful and delicious, consisting of southern Thai dishes. The guests were served water but joked during the performances with alcoholic drinks. Wandi and Leg made a point that the performance was very costly and that not every family could aord this; in a bad year, even Wandi and Leg may have to postpone it. Some details deserve special attention. The spirit-mediums are professional mediums from the city. Family members become possessed, too, but one can say that the urban spirit-mediums returned to the village and merged with the Manooraa Rongkruu. The boundaries become blurred. The ritual was used to treat some patients from the kinship group in the rong; this did not include the host. These sessions between the professional spirit-mediums and the patients were special. The spirit-medium was possessed by powerful ancestor spirits and moved the burning candle in circling movements over the head of the patient who lies on a mat in the rong. Through the therapy, the spirit-medium aimed to remove excess heat and wind, thus exorcising the harmful spirit. My eld notes illustrate the atmosphere of the possession of Wandi by the ancestor spirits of the family:

The Nai Manooraa, his wife, his assistant and the musicians invoke the ancestors with loud verse. Wandi, the female head of the household, appears as a medium and embod-

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

927

ies the powerful spirit of the domain. The spirit accepts the oering by Wandis eating of the re. The trancer returns ecstatically with the candle in her hand to the shrine in the house, to pay her respect to the deities in the house, moves back to the rong and climbs the ladder to the palai to venerate the great teachers before returning to the core family where the spirit meets the family members, beginning with the oldest grandfather and proceeding by declining age through to the daughter. In great emotional warmth, she hugs and embraces the family members and tears are shed, because the ancestors have not seen the living for a long time. The spirit is joking and laughing with family members and the community. The ancestors inquire about the status of the family and provide valuable advice. Then, Wandi is waning, fully exhausted, to rewake later as Wandi.

The Manooraa Rongkruu: Between Healing, Social Reputation and Prosperity Cult Spirit possession is a technique to cope with aiction and illness, in which the host possessed by a spirit speaks in the manner and tone, and performs the role of the spirit to communicate through bodily movements with the clients (Tanabe, 2002:58). The Manooraa Rongkruu is a healing ceremony in which the social relations of the living and the dead are refreshed and by which the ancestors speak to the living. People in Thailand believe if the life essence leaves the house, its inhabitants are left vulnerable to spirit attack. The motivations to stage a Manooraa Rongkruu ceremony are manifold:

The therapeutic function is among the most important. In the case of the host in Sichon, Nakhornsrithammarat, the head of the family lost her voice and regained it only after requesting it from her ancestors. She vowed that she would host a Manooraa every year. In Songkhla, Wandi was not in good shape. In a third case, the head of the family again felt depressed. In the Manooraa Rongkruu, the ancestor spirits are called to exorcise evil from the house and the community, to tame the malevolent spirits and to rebalance the fragile equilibrium of benevolent and malevolent spirit forces.

The Manooraa helps boost the economy of the household. In Songkhla, the nairong Manooraa told the audience that the spirits are appeased and that the host family will be rich and healthy. The Manooraa Rongkruu ceremony has become a costly enterprise as the Manooraa troupe normally does not receive any sponsorship. The host has to pay for the artists, dancers, costumes and stage and, most costly, for the food to entertain the guests. Every guest, whenever she or he arrives, should be properly served. The guests also donate some money to the hosts but the donation will not cover the expenses. Hence, the poor cannot aord the Manooraa and the performance. That said, the poor can ock to the Manooraa ceremonies in the village, enhancing the benefactor status of the host family or to the big spectacles in Takae or Takura.

928

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

The enchanting arena of the Manooraa Rongkruu reects highly contradictory modernisation processes. Although the poor can hardly aord to host a performance, they are not excluded from the audience and are equally fed. They participate in the preparation of the dishes and elaborate oerings. The rich hosts hold Manooraa Rongkruu performances in which they display their power and wealth. The choice of the Nai Noora, the decoration of the stage, the oerings, the choice of the spirit medium, and the food all inuence the representation of the host in the community. Thus, the Manooraa Rongkruu is not only a ritual of communitas, but is a ritual in which power and wealth can be celebrated and in which merit-making is in the hands of the new rich. The Manooraa Rongkruu is used equally to rebuild ones social reputation in the community and kinship group after falling victim to all kinds of modern misfortunes and as an increasingly individual strategy for social, economic and political success. This new meaning of the Manooraa Rongkruu becomes even more evident in the public, spectacular performances of the Manooraa Rongkruu in Wat Takae and in Wat Takae that are sponsored by extremely wealthy temples, the local government or wealthy businesspeople in the area. These public performances attract thousands of pilgrims and worshippers every year. The Manooraa Rongkruu, in honour of the rst teacher in Takae, and the Ta Yai Yarn, in honour of the rst teachers mother, have become highly commodied festivals that, however, keep the intimacy and the spirituality of the original Manooraa epos in which all people are descendents of the rst teachers and are, thus, expected to venerate the great ancestors. The Grand Crowning Manooraa Rong Kru for the First Manooraa Teacher in Wat Takae, Pattalung The ceremony in the temple Wat Takae in Pattalung takes place annually in the last week of April for veneration of the rst teacher of the Manooraa, Khun Si Sata, the son of Mae Simmala, and believed to be a reincarnation of the Hindu god Shiva. Six of twelve Manooraa-founder spirits are said to possess spirit mediums in Wat Takae. The grand ritual in Wat Takae is a public spectacle which attracts hundreds of people from all parts of the South to honour the rst teacher of the Manooraa, Khun Si Sata and to oer him a gift. It is believed that the soul of Si Sata is living in Wat Takae. The Nairong Manooraa who has the privilege to perform in the grand ceremony in Wat Takae is regarded as direct successor of Si Sata and has to be among the greatest living Manooraa teacher in southern Thailand. During the grand Manooraa Rong Kru ceremony at Wat Takae, the

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

929

successor of the rst Manooraa teacher is crowned and accepted as a teacher of the grand Manooraa. The Manooraa teacher derives his power from the spirit of the rst teacher, Khun Si Sata, whose spirit is present and who observes the performance with keen interest. Khun Si Sata is commemorated with a statue that sits like a Buddha in a small Viharn building that has been constructed in the temple to accommodate him. The pilgrims oer owers and food oerings to the spirit of Si Sata in the small Viharn. The great ritual is carried out among the Manooraa-family, which includes all people with Manooraa descent. As nearly all households in old villages are trakun Manooraa, everybody is called upon to join the ceremony in Takae. It is a hot day and huge crowds come to the temple. The event is organised by a committee, which consists of the abbot, local civil servants and prominent businessmen. The main representatives of the preparation committee present the Manooraa Rongkruu at Takae as a Buddhist tradition. One particular businessman in construction and engineering who dresses in the traditional white clothes of the spirit-mediums is the main sponsor of the event. This businessman accumulates huge prestige by sponsoring the ceremony. During the ritual, he will be possessed by the ancestor spirits and dance among other mediums in the pavilion. He is among the designated spirit-mediums that participate every year in the Takae ceremony. Entrance to the stage is restricted by the authority of the Manooraa teacher. Nevertheless, it seems that people come and go and that the stage becomes a very uid space. A hundred onlookers are allowed to stay closely to the stage in the hot sun to observe the spectacle and to comment on it. The music is extremely noisy and loudspeakers blast across the temple terrain. After the performance of the Manooraa dancers, the stage is lled with dancers, and people who wear the Manooraa mask of the hunter. Old women join and begin spontaneously to dance. Spirit-mediums in white clothes join the scene and become successively possessed by the great Manooraa ancestor spirits. The stage is constantly lled with possessed spirit-mediums and dancers, unless the nairong Manooraa calls the dancers from the stage to make space for a ritual. After a break, the Manooraa teacher gives waiting families the possibility to enter the stage and to present their children. Some babies suer from a skin illness that leaves terrifying red sores in the face. As the medical treatment of this illness is dicult and costly, the magical treatment by the Manooraa teacher is a viable alternative. This special ritual- called yiap sen (stepping on the sore) is well known in southern Thailand and has been performed for centuries. In the perspective of the Manooraa, the illness is caused by

930

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

malevolent spirits: a female spirit would have selected the child and, therefore, marked it. According to the legend, Khun Si Sata healed this illness and removed the sores from the faces of two hunters by washing his feet in seawater and putting them on the wounds. The parents bring their babies on the stage and put them on a soft pillow. In the dance the nairong Manooraa bathes his bare foot in a bowl of sacred water and betel leafs. He writes a mantra in old Khmer language on the big toe and puts it into a ame. The rhythm of the music intensies, when the nairong Manooraa moves his foot turns around and touches the face of the child rmly with his bare foot. The musician beats the drums strongly and increases the dramatics. The nairong Manooraa is possessed by the spirit of the rst Manooraa teacher and uses his power and knowledge in the healing ritual. The authority of the nairong Manooraa in healing the sores is unquestioned and widely known in southern Thailand. The yiap sen ritual is repeated several times as many parents come with their babies to the ceremony full of hope that the spirit can be domesticated and bring healing. The climax of the Takae ceremony is the crowning initiation ceremony. The assistant of the nairong Manooraa who was dressed in white clothes during the ritual, is prostrating in front of the nairong Manooraa. There is concentrated silence at this stage as everybody is aware of this precious moment. The nairong Manooraa puts a crown on the head of his assistant, thereby transmitting the power and knowledge of the Manooraa tradition to him. The crowned assistant is now able to found his own Manooraa group and perform with it. The new Manooraa master is now allowed to change his costume and to wear the beautiful costume of the Nai Manooraa. He submits himself under the authority of his teacher for the duration of the ritual, but will eventually succeed him. After the crowning ritual, he carried out his rst performance under the auspices of his teacher and the spirit of Si Sata. During the ritual, the stage is one of the main theatres of action, but in parallel, the image of Si Sata in the small temple building also attracts large crowds who oer candles, owers, incense, betel leaves and food in worship of the rst teacher. In the Takae ritual, only the great ancestors are invited to the boost, including the rst Manooraa teachers, the guardian spirits of the land of Takae, the kings and Buddhist saints. Spirit-mediums and masked dancers feel free to occupy the stage throughout the ritual. Every single ritual, whether in the intimate sphere of the house or in public space, represents the microcosm of the world and the universe in the understanding of the Manooraa. The public performance in Takae attracts hundreds of participants and onlookers who hope to benet from the presence of Si Satas spirit and his power to heal.

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

931

In the rst week of May, another grand ceremony attracts thousands of pilgrims who come in families to ock to participate in the merit-making activities at the temple of Ta Kura in Satingpra. The ritual in Satingpra is also organised by a committee consisting of local bureaucrats and the Buddhist abbot of Ta Kura. The ceremony transforms the sleepy village of Ban Ta Kura into a huge feast in which large crowds are attracted by the healing power of the Buddha image that is stored in a box behind two temple doors. The unwrapping of the small Buddha image under the music of the Manooraa musicians is the highlight of the festival. In addition, hundreds of young women are ordained as Buddhist nuns for one day in fullment of a vow to Mae Simmala.

The Manooraa Rongkruu as Spiritual Experience, Prosperity Cult and Pilgrimage The crowds joining the festivals do so for several reasons. Many come regularly every year as pilgrims to worship the great Manooraa ancestors. They emphasise the importance of the ritual by giving it the attribute: big. Here, the cosmological power is particularly dense. It is, thus, possible to participate in the life essence and to dance to the Manooraa verse even only for a few minutes and for a 50 Baht ticket. My friends join the Ta Yai Yarn every year. They also participate in the ritual of two religions at the cemetery in Ban Tamot, Patthalung, since one of my friends grandparents are buried there. My friends are also interested in Buddhist saints, amulets, and all kinds of Buddhist relics which he collects; he also visits a Buddhist nun regularly who resides alone in the wood. They believe that the Ta Yai Yarn is especially benevolent to women who worship Mae Simmala, the mother of the Manooraa and the mother of southern Thailand. Young women ock to the Ta Yai Yarn in order to full a vow to Mae Simmala, thereby conating Manooraa Rongkruu and Theravada Buddhism. Many people are attracted by the Manooraa troupes that are being considered the greatest in the region and the successors of the great Manooraa teachers who, themselves, passed away and are among the great ancestors. The participants request a boon and reciprocate by dancing with the hunters mask in the temple. People come in large families to party, mingle with the crowds and visit the many market stalls, selling Buddhist amulets, Manooraa music, food and drinks. In Wat Takae, the stepping on the red sore healing ritual is very prominent. Nai Manooraa Sompong is widely known for his delicate dance, for his proximity to the gods and for his healing power. Families come from

932

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

everywhere to have their infants cured through the Nai Nooras foot. All kinds of patients come to have their illnesses or misfortune cured. People come also to worship the rst teacher of the Manooraa epos, Si Sata, and stay for hours in the small pavilion. They come also to consult the spirit-medium which sits in front of the image of Si Sata and is in a state of spirit possession. All this happens in an old Buddhist temple which is fully open for the Manooraa ceremony. All the hotels in the surroundings of Wat Takae are fully booked. Some local teachers describe the Manooraa Rongkruu as a Buddhist art genre and Si Sata as a Buddhist. The Buddhist character of the Manooraa Rongkruu is also underlined in the narrative of the donation of a golden Buddha image by Mae Simmala to Wat Ta Kura and by the ordination of young women as nuns for one day. Perhaps the most interesting case is the arrival of a group with a veiled Muslim woman and a sick baby. Because of her veiling, everybody recognises her as modern Muslima. Some of the Muslim participants may not wear Islamic clothes and are not recognisable as Muslims. This woman made a case in showing o her Islamic aliation but made a desperate move to nd a cure for her baby. She was received by the Nai Manooraa who put his foot on the babys face under some drumming. The Muslim woman was unaware of the commercialisation of the ceremony and was deeply uncomfortable in the crowd. Finally, she bought the ticket and her right to see the Manooraa master for ve minutes. This case shows that even as a modern Muslima, the woman hoped to receive a cure from the great ancestor spirits, in whose power she clearly believed. Although the Manooraa ceremony was performed in a Buddhist temple, the Manooraa Rongkruu remained a multi-religious ritual open for Buddhists, Muslims or any other religion. Nevertheless, the Manooraa Rongkruu ceremony is appropriated by the local government, some businesspeople and the Buddhist Sangha. The Manooraa Rongkruu in the modern era has, thus, changed into a hybridised Buddhist one and few items remind one of its multi-religious character. The relationship between the intimate and the public is an interesting aspect of the Manooraa Rongkruu. Even the mass gatherings in Takae and Takura keep some intimacy that is associated with the possession of the spirit-medium by the great ancestor spirits. As to the private performances where strangers are not allowed (in contrast to the anonymous crowds arriving in Takae and Takura), the Manooraa Rongkruu is a combination of the intimate and the public par excellence. The Manooraa Rongkruu is intimate just as the spirit altar for the ancestors of the house is intimate; it is also public as the performance is open for relatives, friends and neighbours. It would be asocial not to appear for the Manooraa performance.

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

933

Conclusion Early ethnography on the conceptualisation of popular religiosity and the Manooraa seem to be caught in a substantialist and essentialising categorisation of ritual in which the person is conceptualised as a total, unchanging entity. While structuralist concepts have pointed out the importance of exchange of gifts in the interactions between healer and patient, they have limited themselves by ignoring the transformation of the person under external conditions and the religious strategies of the clients and patients to cope with the emotional disturbances they face, as well as with issues of modernity. Exchange models that rely on the reproduction of social relations fail to account for the processes of individualisation of spirituality in a postmodern world. I argue for a more dynamic perspective in which the revitalisation of the Manooraa and its changing functions can be explained more convincingly. To explain the agency of Thai popular religion, we have to consider the new functions of the Manooraa Rongkruu during the economic boom and decline of Thailand in the last few decades. Host families sometimes book a full Manooraa Rongkruu ceremony as a conscious strategy to accumulate merit and to enhance social prestige in the community. I would argue that the decisive factor in the revitalisation of the Manooraa Rongkruu is the individualistic search of the lower- and middle-class for spiritual experience, performance and fullment of their spiritual needs.

References

Bowie, K. A. (1998) The Alchemy of Charity: Of Class and Buddhism in Northern Thailand. American Anthropologist 100(2): 469481. Cohen, E. (2001) The Chinese Vegetarian Festival in Phuket. Religion, Ethnicity and Tourism on a Southern Thai Island. Bangkok: White Lotus. Gesick, L. (1995) In the Land of Lady White Blood: Southern Thailand and the Meaning of History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. Golomb, L. (1978) Brokers of Morality. Thai ethnic adaptation in a rural Malaysian setting. Honolulu: University of Hawaii press. (1985) An anthropology of Curing in multi-ethnic Thailand. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Guelden, M. (2005) Spirit Mediumship in Southern Thailand. The Feminization of Manooraa Ancestral Possession, in Wattana Sugunnasil (ed.), Dynamic Diversity in Southern Thailand. Chiangmai: Silkworm Press. (2007) [1995] Spirits among us. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, Pp. 152181. Hemmet, Christine (1992) Le Manooraa du Sud de la Thailande: un culte aux ancetres, BEFEO 79, 2: 261282. Horstmann, A. (2004) Ethnohistorical Perspectives on Buddhist-Muslim Relations and Coexistence in Southern Thailand. From Shared Cosmos to the Emergence of Hatred? SOJOURN, Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 19(1): 7699.

934

A. Horstmann / Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (2009) 918934

Jackson, P. A. (1999a) Royal Spirits, Chinese Gods, and magic monks: Thailands Boom-time religions of prosperity. SEAR 7(3): 245320. (1999b) The enchanting spirit of Thai capitalism: The cult of Luang Phor Khoon and the post-modernization of Thai Buddhism. Southeast Asia Research 7(1): 560. Knauft, B. M. (2002) Critically Modern: Alternatives, Alterities, Anthropologies. Indiana University Press: Bloomington. Morris, R. C. (2000) In the Place of Origins. Modernity and its Mediums in Northern Thailand. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Muecke, M. (1979) An explication of wind illness in Northern Thailand, Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 3: 267300. Parichat Jungwiwattanaporn (2006) In Contact with the Dead: Manooraa Rong Khru Cha Ban Ritual of Thailand. Asian Theatre Journal 23(2): 374395. Pattana Kitiarsa (2002) You may not believe, but never oend the spirits. Spirit-medium cult discourses and popular media in modern Thailand, in T. Craig and R. King (eds.), Global goes Local. Popular Culture in Asia. Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press. (2005a) Beyond Syncretism: Hybridization of Popular Religion in Contemporary Thailand. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 36(3): 461487. (2005b) Magic Monks and spirit mediums in the politics of Thai popular religion. InterAsia Cultural Studies 6(2): 209226. Phittaya Butsararat (1992) Manooraa Rongkruu, Tha Khae Village, Phatthalung Municipal District, Patthalung Province. M.A. thesis, Srinakharinwirot University. (2003) The Change and Relations between Society and Culture in the Low Lying Areas of Songhkla Lake. The Case Study of Nang Talung and Manooraa after the Government Reformation in the Period of King Rama the Fifth to the Present Day. Presented at the Conference The Tendency of Changes of Songkla Lake: History, Culture, and Developing Vision. The Institute for Southern Thai Studies, Songkhla, Thailand (in Thai). Tanabe, S. (2002) The Person in Transformation: Body, Mind and Cultural Appropriation, in S. Tanabe and C. F. Keyes (eds.), Cultural Crisis and Social Memory. Politics of the Past in the Thai World. London/New York: Routledge/Curzon. Taylor, J. L. (1999) Postmodernity, remaking tradition and the hybridization of Thai Buddhism. Anthropological Forum 9(2): 163187. Thienchai Isaradej (1999) Social Implications of Manooraa Rongkruu: A Case-Study of Ban Bo-Dang. M.A. Thesis, Silapakorn University (in Thai). (2003) Manooraa Rongkruu: The Ritual of Personality Formation of the South, in Jaomae Khunpuu Changsaaw Chaangfawn and other Stories about Ceremonies and Theatre Arts. Bangkok: Sirithorn Anthropology Centre (in Thai).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- ACCOUNTING FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION FUNDSDocument12 pagesACCOUNTING FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION FUNDSIrdo KwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Monson, Concilio Di TrentoDocument38 pagesMonson, Concilio Di TrentoFrancesca Muller100% (1)

- Current Events Guide for LET TakersDocument7 pagesCurrent Events Guide for LET TakersGlyzel TolentinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Annexure 2 Form 72 (Scope) Annexure IDocument4 pagesAnnexure 2 Form 72 (Scope) Annexure IVaghasiyaBipinPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs Drilon Guidelines on Deployment BanDocument1 pagePhilippine Association of Service Exporters vs Drilon Guidelines on Deployment BanRhev Xandra AcuñaPas encore d'évaluation

- NAME: - CLASS: - Describing Things Size Shape Colour Taste TextureDocument1 pageNAME: - CLASS: - Describing Things Size Shape Colour Taste TextureAnny GSPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Literature CircleDocument10 pagesFinal Literature Circleapi-280793165Pas encore d'évaluation

- USP 11 ArgumentArraysDocument52 pagesUSP 11 ArgumentArraysKanha NayakPas encore d'évaluation

- G11SLM10.1 Oral Com Final For StudentDocument24 pagesG11SLM10.1 Oral Com Final For StudentCharijoy FriasPas encore d'évaluation

- Supplier of PesticidesDocument2 pagesSupplier of PesticidestusharPas encore d'évaluation

- BOM - Housing Template - 6.27.22Document4 pagesBOM - Housing Template - 6.27.22Eric FuentesPas encore d'évaluation

- Torts and DamagesDocument63 pagesTorts and DamagesStevensonYuPas encore d'évaluation

- Adjusted School Reading Program of Buneg EsDocument7 pagesAdjusted School Reading Program of Buneg EsGener Taña AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Alsa Alsatom MB, MC - Service ManualDocument26 pagesAlsa Alsatom MB, MC - Service ManualJoão Francisco MontanhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Planning and Program Budgeting in Romania RecentDocument6 pagesStrategic Planning and Program Budgeting in Romania RecentCarmina Ioana TomariuPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Science Assignment PDFDocument6 pagesPolitical Science Assignment PDFkalari chandanaPas encore d'évaluation

- MadBeard Fillable Character Sheet v1.12Document4 pagesMadBeard Fillable Character Sheet v1.12DiononPas encore d'évaluation

- AmulDocument4 pagesAmulR BPas encore d'évaluation

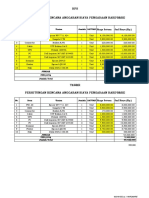

- HPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANDocument2 pagesHPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANYanto AstriPas encore d'évaluation

- A Review Article On Integrator Circuits Using Various Active DevicesDocument7 pagesA Review Article On Integrator Circuits Using Various Active DevicesRaja ChandruPas encore d'évaluation

- A Christmas Carol AdaptationDocument9 pagesA Christmas Carol AdaptationTockington Manor SchoolPas encore d'évaluation

- Bhojpuri PDFDocument15 pagesBhojpuri PDFbestmadeeasy50% (2)

- Eating Disorder Diagnostic CriteriaDocument66 pagesEating Disorder Diagnostic CriteriaShannen FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Document16 pagesReading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Ericka Marie AlmadoPas encore d'évaluation

- All About Linux SignalsDocument17 pagesAll About Linux SignalsSK_shivamPas encore d'évaluation

- McKesson Point of Use Supply - FINALDocument9 pagesMcKesson Point of Use Supply - FINALAbduRahman MuhammedPas encore d'évaluation

- 20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesDocument58 pages20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesLin Xinhui75% (4)

- Protein Synthesis: Class Notes NotesDocument2 pagesProtein Synthesis: Class Notes NotesDale HardingPas encore d'évaluation

- Epq JDocument4 pagesEpq JMatilde CaraballoPas encore d'évaluation

- 001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxDocument2 pages001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxTelle MariePas encore d'évaluation