Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Bleach

Transféré par

idontcareassDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Bleach

Transféré par

idontcareassDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

West Virginia University Extension Service

WL 314

CHLORINE AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Joyce E. Meredith, Ph.D. Extension Specialist Science and Technology Education The element chlorine is part of many different substances, including common table salt (sodium chloride). Elemental chlorine gas does not exist in nature, but it can be produced by a process which separates the sodium from the chlorine in saltwater. This elemental chlorine reacts strongly with other substances, particularly those containing the element carbon. The substances resulting from these reactions between chlorine and carbon compounds are called organic compounds of chlorine. According to Technology Review magazine, chlorine and its compounds are used in about 15,000 products having estimated annual U.S. sales of $71 billion. Chlorine is used to produce polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics, herbicides, pesticides, and pharmaceutical drugs; to bleach pulp and paper; and to disinfect drinking water. In addition to the 15,000 chlorine products manufactured by humans, nature releases 1,500 to 2,000 chlorine compounds to the environment. What's the problem with chlorine? Chlorine compounds and their by-products are suspected to cause a number of environmental and human health problems. One of the earliest examples of this problem was the pesticide DDT, an organic compound of chlorine which imitates the action of certain hormones like estrogen. In the 1950s populations of several bird species, including the bald eagle, dropped drastically. It was suspected that DDT in the environment caused female birds to produce eggs with thin shells, and caused males to be born with feminized reproductive organs. Another group of chlorine compounds, the polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), has had similar effects in birds and fish of the Great Lakes region. PCBs were once used widely in the electrical industry. Yet another group, the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), breaks down the Earth's protective ozone layer. CFCs have a multitude of uses, including serving as refrigerants in air conditioners and refrigerators, as an ingredient in polystyrene (Styrofoam), and as propellants for aerosol cans. DDT and PCBs are now banned in the United States, and CFCs are being phased out. Still, these chemicals will remain in the environment for years to come, as will their harmful effects. Furthermore, many scientists believe certain stilllegal chlorine compounds may imitate human hormones, causing serious health problems, such as low sperm counts, testicular cancer, and breast cancer. Also, the dioxinswhich are by-products of combustion, industrial processes involving chlorine, and chlorine bleaching of pulp and paperare known to cause cancer in laboratory animals. Some organic compounds of chlorine are persistent. That is, they do not biodegrade, or break down, very easily. Some of these compounds bioaccumulate in fat tissues. Also, some chlorine compounds biomagnify, meaning the concentration of the compounds gets higher in animals higher up the food chain. So, larger animals that feed on smaller animals, as human beings do, can be expected to have higher concentrations of these chlorine compounds in their bodies. Not everyone agrees that chlorine compounds pose a serious threat to the environment and to human health. Scientifically proving a direct link between chlorine and a human health problem is difficult because it is hard to isolate the effects of any one chemical from those of many other chemicals that may be present in the environment. Determining what dose of a chemical should be considered dangerous is also difficult. Some scientists believe the level of chlorine compounds present in the environment is not high enough to cause real problems.

What should we do about chlorine? Some feel the risks associated with chlorine are great enough that it should be banned altogether. In 1992, the International Joint Commission (IJC), an environmental advisory group organized by the U.S. and Canadian governments, formally recommended that the use of chlorine and chlorine compounds be phased out. The IJC recently renewed this recommendation in its 1994 biennial report. Greenpeace, an outspoken environmental organization, supports the chlorine ban, but so does the National Wildlife Federation, widely considered to be a moderate environmental group. Industry's position on the chlorine issue is represented by various organizations, including the Chlorine Institute, a nonprofit association of more than 200 chemical industry companies. The Chlorine Institute describes its mission as supporting industry and serving the public by promoting safe use of chlorine. The institute argues that chlorine and its compounds are essential to modern life, and that a complete ban on chlorine would be very costly to society. Instead, industry recommends evaluating each chemical individually and banning only those found to be harmful. This is the system the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) uses to regulate chemicals. On the other hand, the International Joint Commission argues that individually evaluating chemicals is a slow and tedious process, much too slow to adequately protect the environment and human health. They believe enough evidence exists to eliminate the use of all chlorine compounds. One option that industry currently has is to voluntarily cut back on the use of chlorine and chlorine compounds, replacing them with other chemicals and other ways of accomplishing the same tasks. However, shifting to chlorine-free technologies is likely to be expensive and timeconsuming. And in some cases, the chlorine-free technologies may turn out to be as bad, or worse, for the environment as chlorine. State governments can examine their existing laws and regulations to evaluate whether they provide

adequate protection to the environment and human health. For example, at the request of the governor, the Michigan Environmental Science Board carried out a six-month investigation of the chlorine issue. In its 1994 report, the board concluded that certain chlorine compounds, namely those that are toxic at low levels and are persistent in the environment, should be of concern. However, the board also concluded that a complete phase out of chlorine, as recommended by the International Joint Commission, is not necessary. At the federal level, the EPA has announced that it will "develop a national strategy for substituting, reducing, or prohibiting the use of chlorine and chlorinated compounds." The agency will form a task force to study the risks associated with chlorine and the possibilities of substituting chlorine-free technologies for those using chlorine. Some suggest that the EPA is taking a middle ground with this action. Additionally, the EPA will release a new reassessment of the health effects of dioxins. This report is due to be released in late 1995. What can you do about the chlorine problem? Here are some ways you can reduce the amount of chlorine and chlorine compounds that make their way into the environment. * * * * Use water-based paint removers, which do not contain chlorine compounds. Minimize your use of insecticides around the home and garden. Avoid dry cleaning your clothes. The dry cleaning process uses a chlorine compound. Use fewer plastic and vinyl products. Particularly avoid plastics with the number 3 recycling symbol, which indicates they are PVC, or polyvinyl chloride. Use unbleached paper products. Use less chlorine bleach.

* *

1995: 5M

Trade or company names are given for information only. No endorsement or recommendation to the exclusion of other products that also may be suitable is intended. Programs and activities offered by the West Virginia University Extension Service are available to all persons without regard to race, color, sex, disability,religion, age, veteran status, sexual orientation or national origin. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Director, Cooperative Extension Service, West Virginia University.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- PM TB Solutions C07Document6 pagesPM TB Solutions C07Vishwajeet Ujhoodha100% (6)

- Vibration of Two Degree of Freedom SystemDocument23 pagesVibration of Two Degree of Freedom SystemDewa Ayu Mery AgustinPas encore d'évaluation

- C4.1 Student Activity: Amount of SubstanceDocument7 pagesC4.1 Student Activity: Amount of SubstanceOHPas encore d'évaluation

- Horizontal or Vertical Installation Check ValvesDocument5 pagesHorizontal or Vertical Installation Check ValvesAVINASHRAJPas encore d'évaluation

- WEST SYSTEM Product LiteratureDocument8 pagesWEST SYSTEM Product LiteraturecockybundooPas encore d'évaluation

- CW Cat enDocument44 pagesCW Cat enStefanArtemonMocanuPas encore d'évaluation

- Mining and Fisheries ResourcesDocument19 pagesMining and Fisheries Resourcesedenderez094606100% (2)

- Combustion Analysis Extra Problems KeyDocument2 pagesCombustion Analysis Extra Problems KeyJoselyna GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Calculation Pressure DropDocument9 pagesCalculation Pressure DropdasubhaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Polymers Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials 3rd Edition by J M G Cowie and V ArrighiDocument2 pagesPolymers Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials 3rd Edition by J M G Cowie and V Arrighiwahab0% (1)

- 8.4 Performance Qualification Protocol For Dispensing BoothDocument13 pages8.4 Performance Qualification Protocol For Dispensing BoothArej Ibrahim AbulailPas encore d'évaluation

- Ce 259 11819 #08 Response SpectraDocument11 pagesCe 259 11819 #08 Response SpectraLuis Ariel B. MorilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuclear Fusion PowerDocument11 pagesNuclear Fusion PowerAndré RebelloPas encore d'évaluation

- CENG 122 Fall 2014 Syllabus Zhang CurriculumDocument3 pagesCENG 122 Fall 2014 Syllabus Zhang Curriculumtcd_usaPas encore d'évaluation

- "Mechanical Measurements" T. Beckwith, R. Marangoni, and J. Lienhard, Sixth Edition, Pearson Prentice Hall 2009Document2 pages"Mechanical Measurements" T. Beckwith, R. Marangoni, and J. Lienhard, Sixth Edition, Pearson Prentice Hall 2009Timothy FieldsPas encore d'évaluation

- ThermodynamicsDocument8 pagesThermodynamicsZumaflyPas encore d'évaluation

- Direct Water Injection Cooling For Military E N G I N E S and Effects On The Diesel CycleDocument11 pagesDirect Water Injection Cooling For Military E N G I N E S and Effects On The Diesel Cycledipali2229Pas encore d'évaluation

- BISMUTO NUEVO Id4-Bis PDFDocument11 pagesBISMUTO NUEVO Id4-Bis PDFCarlos BarzaPas encore d'évaluation

- AFR - Turbine PDFDocument20 pagesAFR - Turbine PDFChetanPrajapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Powerpoint in ConchemDocument12 pagesPowerpoint in ConchemCrystel EdoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Concrete Reinforcement and Glass Fibre Reinforced PolymerDocument9 pagesConcrete Reinforcement and Glass Fibre Reinforced PolymerchanakaPas encore d'évaluation

- Heterocyclic CompoundsDocument26 pagesHeterocyclic Compounds29decPas encore d'évaluation

- Ti O2Document4 pagesTi O2Muhamad Fahmi Dermawan EndonesyPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemical Thermodynamics Y: David A. KatzDocument44 pagesChemical Thermodynamics Y: David A. Katztheodore_estradaPas encore d'évaluation

- Iso 5418 1 1994Document9 pagesIso 5418 1 1994Faiza MarrakchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Experimental Investigation On Black Cotton Soil Treated With Terrabind Chemical and Glass PowderDocument12 pagesExperimental Investigation On Black Cotton Soil Treated With Terrabind Chemical and Glass PowderIJRASETPublicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- PPU NotesDocument38 pagesPPU Noteswadhwachirag524Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Report Experiment 1Document5 pagesLab Report Experiment 1Jessica NicholsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Decomposition of A Multi-Peroxidic Compound: Triacetone Triperoxide (TATP)Document8 pagesDecomposition of A Multi-Peroxidic Compound: Triacetone Triperoxide (TATP)mwray2100% (1)

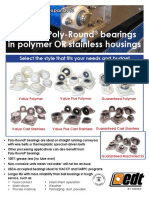

- Solution Poly-Round Bearings in Polymer OR Stainless HousingsDocument3 pagesSolution Poly-Round Bearings in Polymer OR Stainless HousingsLeroy AraoPas encore d'évaluation