Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Natalia 27 (1997) Complete

Transféré par

Peter CroeserTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Natalia 27 (1997) Complete

Transféré par

Peter CroeserDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

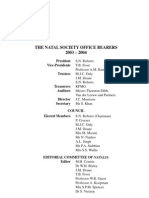

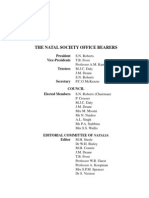

THE NATAL SOCIETY OFFICE BEARERS 1997

President

Vice-Presidents

Trustees

Treasurers

Auditors

Director

Assistant Director and

Secretary to the Council

M.le. Daly

Dr F.C. Friedlander

TB. Frost

S.N. Roberts

M.le. Daly

A.B. Burnett

S. N. Roberts

KPMG

Messrs Thomton-Dibb,

Van der Leeuw and Partners

Mrs S.S. Wallis

le. Morrison

COUNCIL

Elected Members MJ.C. Daly (Chairman)

S.N. Roberts (Vice Chairman)

Professor A.M. Barrett

A.B. Bumett

lH. Conyngham

1.M. Deane

T.B. Frost

Professor W.R. Guest

Professor A. Kaniki

H.Mbambo

Mrs S. Msomi

Mr::; TE. Radebe

Mrs J. Rosenberg

A.L. Singh

Ms P.A. Stabbins

Transitional Local Council Professor e.O. Gardner

Representatives N.S. Madlala

E. O. Msimang

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE OF NATALIA

Co-editors 1.M. Deane and TB. Frost

Dr W.H. Bizley

M.H. Comrie

Professor W.R. Guest

Dr D. Herbert

F.E. Prins

Mrs S.P.M. Spencer

Dr S. Vietzen

Secretary DJ. Buckley

Natalia 27 (1997) Copyright Natal Society Foundation 2010

Natalia

Journal ofthe Natal Society

No.27 December 1997

Published by Natal Society Library

P.o.Box 415, Piet.ermaritzburg 3200, South Africa

SA ISSN 0085-3674

Cover Picture

Vasco da Gama and Adamastor (Illustration from an

1880 edition ofCamoens's The Lusiads)

H] am that mighty hidden cape, called by you Portuguese the Cape of

Storms ... This promontory of mine, jutting out towards the South Pole,

marks the southern extremity of Africa. Until now it has remained

unknown: your daring offends it deeply. Adamastor is my name ... "

Canto 5 (W.e. Atkinson's 1952 translation)

Typeset by M.J. Marwick

Printed by The Natal Witness Printing andPublishing Company (Pty) Lld

Contents

Page

EDITORIAL ................................................ 5

UNPUBLISHED PIECE

Catherine Portsmouth's letter

Shelagh Spencer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . 6

ARTICLES

Vasco da Gama and the naming of Natal

Brian Stuckenberg .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

What Da Gama missed on his way to Sofala

illobane: a new perspective

Scratching out one's days

Gavin Whitelaw . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Huw Jones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Adrian Koopman ........................................ 69

OBITUARIES

Dennis Gower Fannin .. . . . . .. . .. . . . . . .. . . . . . .. .. . . . . .. .. . 92

Philip Rudolf Theodorus Nel ............................. 93

Gerhardus Adriaan ('Horace') RaIl ....................... 94

Nicholas Arthur Steele ... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

Auret van Heerden . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

NOTES AND QUERIES 101

BOOK REVIEWS ..... . 117

SELECT LIST OF RECENT

KWAZULU-NAT AL PUBLICATIONS 128

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

16th Century navigators using the nautical astrolabe and cross-staff.

(Illustration in the Warhaftig Historia, Magdeburg, 1557)

Editorial

It would be unthinkable for a journal named Natalia, with the remit that it has, not

to note the special significance of this issue's publication date. December 1997

marks the 500th anniversary of Vasco da Gama' s voyage up the south east Mrican

coast on his way to India. His naming of Terra de Natal on Christmas Day 1497 is

taken as the beginning of European contact with this part of the continent.

For years there has been doubt as to whether Natal is in fact the 'Christmas

Land' seen by Da Gama. Professor Eric A'{elson's researches led him to believe that

on Christmas Day 1497 Da Gama's three ships - the San Gabriel, the San Raphael

and the Berrio - were probably much further south, off the coast ofPondoland.

In this issue we publish the results of Dr Brian Stuckenberg's reconsideration of

the evidence, his conclusion being that the Portuguese flotilla was indeed in 'Natal

waters' when the historic naming took place. There is also an article by Gavin

Whitelaw discussing the people, social organisation and occupations Da Gama

would have encountered if he had landed and explored the country he had named.

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 continues to attract the attention of scholars, and

Huw Jones has provided an article which casts fresh ligllt on the Battle of Hlobane,

where Wood's forces suffered a serious reverse on 28 March 1879, prior to the

victory at Khambula. Anticipating the approaching Anglo-Boer War centenary, we

carry a previously unpublished letter by a very ordinary Englishwoman, Catherine

Portsmouth, who had the misfortune to be living near Van Reenen's Pass when

hostilities broke out in 1899. She and her family found themselves virtually at the

point of contact between the British and Boer forces.

After the old Burger Street Prison in Pietermaritzburg was decommissioned, and

before the buildings were repainted for their new use, two students in the

university's Department of Zulu studied the graffiti left by prisoners on cell walls.

Adrian Koopman has turned these observations and notes into an interesting account of

the attitudes and experiences of prisoners in recent years in that grim old place.

Notes and Queries continues to provide items of interest. Readers of Natalia are

invited to contribute short pieces appropriate to this section, or respond to items that

appear in it. The usual obituaries, book reviews and select list of recent KwaZulu

Natal publications complete the contents of this edition.

Together with the order form for Natalia 28, readers will find infomlation about

back numbers of the journal that are still available - some at really give-away

prices. This is an opportunity for subscribers of more recent date to acquire an

almost complete set of Natalia, going back to its first issue in 1971.

lM. DEANE

Catherine Portsmouth sletter

to herfamily in England, about her experiences during the

first 6 Inonths of'the Second Anglo-Boer War

Background

Catherine Portsmouth (1846-1933), bom Matthews, was the widow of Job Portsmouth

(1845-1895), who was bom in Basingstoke, Hampshire, while Catherine's birthplace was

nearby Rotherwick. Portsmouth arrived in Natal in 1874. He established a store and

forwarding agency at Good Hope, one mile south of what came to be lyford, and also a

stable for post-cart horses. Later he purchased 103 acres of the fanu Wagtenbeetjes Kop. This

was named Wyford, after the farm Wyeford, near the village of Sherbome St John, north of

Basingstoke, where Catherine had lived.

Catherine landed in Durban in December 1878 and the two were married in January 1879

after an eleven-year courtship. At first they lived in two wood-and-iron rooms behind the

store and stable, with an outdoor kitchen. In 1882 the substantial store and residence were

completed.

Four children were bom to the couple, viz. William (1881-1958), Elizabeth (1883

1887), Henry (bom 1885) and Catherine Dorothy (the 'Kittywee' of the letter, who was bom

in 1888).

Astride the road from Ladysmith to the Free State, as it was, the UnderberglGood

HopelWyford area almost constituted a village. (This Underberg should not be confused with

the present village of that name in the Southem Drakensberg.) Post-carts passed each way

daily, and for eight months of the year numerous wagons lumbered through, averaging 3 000

a month. Besides the Portsmouths' store and post-cart stage, there was the Good Hope Hotel,

a boarding-house, two blacksmith shops, a police station (with a staff of 10 to 15), a customs

house and a sheep-dipping officer. All this changed with the opening of the railway line to

the Free State border in 1891. The boarding-house and the smithies closed, the police station

was moved half-way up the pass, while the customs house was relocated at the village of Van

Reenen, seven miles away.

When the Second Anglo-Boer War broke out, the Portsmouth household consisted of

Catherine and her ten-year-old daughter, Richard Kermode (Dick) Sansbury (1869-1958),

the store manager, his two sisters Essie and Lilian, a guest, Jack and Mr Smith who

worked in the store. The Portsmouth sons, William and Henry, were in Durban, William

working, and Henry at school.

Once the of Ladysmith was lifted Mrs Portsmouth went to Durban to see her sons.

All the Portsmouths retumed to Wyford in June 1900. Their existence in a 'no man's

land' between the Boers and the British ended in August, when the latter occupied the

village of Van Reenen. Despite Mrs Portsmouth's efforts to remain on her property, the

tamily was evacuated in July 1901, orders having been given for the removal of all residing

within twenty miles of the border.

Natalia 27 (1997), S. Spencer pp. 6-18

7 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

A tew months later, in October, tUrther troubles a111icted the tamily. Henry Portsmouth,

Dick Sansbury and two others were arrested for high treason, accused of having provided the

Boer forces with supplies. Fortunately they were acquitted in April 1902, there being no

evidence to support the charge.

In June 1902 the family retumed to Wvford, where, in Henry's words, they had to 'start

a1resh trom rock-bottom to build it up as a prosperous fann and store and to rc-establish the

home' The British had been using the property as a remount depot and veterinary hospital.

Both Job and Catherine Portsmouth arc buried at Wyford.

Much of the above Portsmouth intormation is taken from a record \\Titten atler 1960 by

Henry Portsmouth, before the farm passed out ofthe family.

The copy of the letter used for publication is a typewritten precis of Mrs Portsmouth's

diary. The latter was written in an exercise book, and was in existence up to the begitming of

the Second World War, when it was lent to friends and never returned. There are anomalies

in the spelling of Dutch names. Mrs Portsmouth could have been responsible for some, e.g.

Pretorias for Pretorius and Coetze for Coetzee, but van Roya/van Royer instead of van

Rooyen, and Bylor for Byloo, vander Lure/van der Leeman for van der Leeuw, and Rinsloo

instead of Prinsloo might have occurred in the original transcription.

The editor would like to thank Mr Alan Povall of Hillcrest, Natal, for lending the copy of

the letter and Henry Portsmouth's notes, and to Mr and Mrs Hubert EltIers of St Albans,

Hertfordshire, for giving pennission for publication. Mrs Shirley Elffers is the daughter of

Henry Portsmouth.

Mrs Portsmouth's grammar and punctuation have been len unchanged.

Underberg, Natal

South Africa.

Nov. 19th, 1899.

To my beloved friends in the old country; who will be interested to read the

experiences of the little party in the Underberg home, during the terrible war

between the Dutch and English, and of our share in all that was so painful, from

October 11th till March 23rd 1900.

My letter expressed some of the fears which filled our hearts, but I purposely

refrained from stating that there was a possibility of our being in danger here, being

so near to the Free State border. In all the up country districts every home (with few

exceptions) was left; the inmates going down nearer the coast. I was advised to do

so. for weeks this was a matter of special prayer to be guided rightly and I believe

and still believe. I was led to stay here, and as my story is told I think my dear

friends will think so too.

My last letters to the dear ones at Rose Hill and to Hursted were written on the

11th and 12th of October - just as the Boers were massed at Van Reenen. We sent

a Kafir boy, at some risk, through to Ladysmith with letters. He broUgllt back a few,

and we were told that all letters for the upper districts were to be held at the GPO,

Maritzburg (what a pile must be there for us). Cousin Mary's of Sept. 22nd I

received on Oct. 19th. The two letters from my boys which I looked for did not

come, neither did Lillie get any from Mr Chapman I.

On the 12th and 13th of Oct. the Boers could be seen at the very top of the

mountains round the Berg and with a field glass we could see them facing their big

guns.

8 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

Saturday 14th, a day, the close of which will ever stand out as the most terrible

of all to us. In the morning Mrs W Scott

2

came over begging us to find some way for

her to get into Ladysmith, she was in a great state of fear and excitement. Dick and I

talked it over and decided to let her have the waggon, and start that afternoon, it

was a risk we knew. All was bustle and confusion, and in the midst of it all, a

gentleman drove into the yard with a lady n u r s e ~ the lady nurse had been attending

a case in Harrismith, and was wanting to get through to Natal (Durban really)

before hostilities commenced. The gentleman had been kind enough to offer to get

her down as far as Underberg. She went on in the waggon with Mrs Scott. The

gentleman was Mr Meiring

3

, the head of the Free State Customs, he was well

known to the Sansburys in Harrismith, and to Mr Fraser. In Bloemfontien they met

as friends. After the waggon had started Mr Meiring said to me, 'Mrs Portsmouth

my horses have come all the way from Harrismith and are pretty well knocked up,

will you hire me a pair to go up the Berg?' I said at once, 'Is it safe?' and he replied

with great dignity, 'perfectly safe. I will see your horses safely returned with

whoever takes mine up.' Then I appealed to Dick, who also said, 'It is alright (sic)

with Mr Meiring.' Mr Fraser offered to take the horses up. My two horses were put

into the spider, and then it was found that Mr Meiring's were not riding horses and

so could not be ridden up the Berg. At last Dick took them in hand and drove them

up before him. Mr Fraser was with him. I was in the kitchen preparing food for

some refugees who had come through from Harrismith. Some time after Mr Fraser

returned saying, 'Dick insisted on going himself as the horses were such a trouble.'

Seven o'clock and no Dick, eight o'clock and then we began to fear. Another

hour told us plainly something was wrong. Oh! what a night that was and the next

day (Sunday) it was terrible. We slept that night from pure exhaustion of body and

spirit, then the awakening Monday morning [October 16th] to the agony of it all, to

what it meant to poor Dick and ourselves. I think in my heart I said, 'God has

forsaken me.' I thank him the darkness did not last long. The morning hours passed

away, about twelve 0' clock we saw on one of the distant hills a commando of Boers

moving along, and an hour and a half later they passed our home. We saw them

coming, and thought it best to shew ourselves. Mr Fraser and Mr Smith

4

went on to

the verandah in front of the store, Essie, Lillie and I, with Kittywee clinging to me,

stood by the open dining room window. The Boers, a rough low looking lot of men,

all armed, about 50 in number, halted outside the gates. We waited scarcely

wondering, hardly feeling. Then Mr Fraser walked boldly down to them, asked if

they wished to come in, they said no, and began to move on at once. When they had

all passed and we knew we were safe for that time, the reaction from the strain

came. Poor Kittywee burst into tears, and the girls and I were very shaky. Mr Byloo5

came back from his dinner, just as the last were passing, and he hurried to enquire

for 'Mr Sansbury,' one answered, 'Oh yes, we have him a prisoner, and he is being

sent to Harrismith.' The poor Kaffirs all ran into the bushes near to hide, and stayed

till the Boers were at a safe distnce. A little later a message came from our

neighbours the Pretoriuses

6

to tell me the Field Cornet was coming to see me. In a

few minutes he was here. I went into the dining room to him, he rose and said, 'Mrs

Portsmouth I believe, I am Field Comet van Rooyen and I have called to tell you

that you will be perfectly safe here, so long as you stay quietly in your home and

9 Catherine Port.smouth's letter

remain perfectly neutral. You will not be interfered with. our men will receive

orders not to touch you or destroy your property or anything belonging to you.' Then

we enquired about Dick, and I told him exactly how he had come to be up the Berg,

he listened. and said he was sorry for us, but we might rest assured that he was quite

safe. We pleaded for his release. this he gave no hope of till the war was over, but

that would not be long he said. He was very angry with Mr Meiring and said he had

no authority to take an Englishman into the Laager

7

and he too had been arrested.

He gave me permission to write to Dick an open letter, and he took it and promised

it should be delivered, which it was, but Dick was not allowed to write to us. They

tried to suspect him of being a spy. WelL we were thankful for so much mercy

vouchsafed to us that day, some of the burden was lifted from our hearts, and to me

there was a sweet thought that my staying here had saved this dear home from being

ruined. Perhaps my boys will value it all the more ,,,hen they understand at what a

cost it was saved. How good for us that we can only see a step before us.

INovember] 23rd. Before I go on with the history of the days succeeding those of

which I have written. I must tell of the great joy which came to us yesterday, 22nd.

Dick came back to us safe and well, his return was a direct answer to prayer. Oh

what a day it was to us, I shall be able to write quite differently now, because my

heart is brimming over with thankfulness.

Our friends the Bloys8 left their home on - of Oct.

9

, they are just on the border,

it seemed wiser to do so, more so, because Mr Bloy is a very strong politician, and

was well knmvn and intensely hated by his Dutch neigllbours. How sad they were

over leaving their home and all the work of years, not knowing how or when they

migllt return. It was well for them they left that day. Mrs Bloy and her daugllters

went by train Monday morning. Mr Bloy drove down the next morning to his farm

at Colenso. Now the Boers have reached Colenso. and we wonder and long to know

if these friends are safe.

After Mr van Rooyen had told us we were quite safe here, he talked of Mr Bloy.

They had been to his house that morning

lO

, broken it open, looted all they could

found his diary or letter book in which he said there was enough to condemn him.

He was a rebel, a traitor, and he would shoot him if he saw him and told his men to

do the same: he would not trouble to bring him to trial. Strange unreasonable talk,

seeing Mr Bloy was not under Dutch rule, but under British. Then he went on to

say: that Natal was their country, indeed the whole of South Africa was, the English

had no business with it. He said, 'We have taken Mafeking (not true), we are taking

Dundee today (not true), then we shall take Ladysmith and very soon be in Durban,

and plant our flag 12 miles on the other side of Durban.' This greatly amused us,

this was the man from whom we thOUgllt we were accepting a kindness, we had to

sit and listen. Afterwards we heard that orders had been given to the men not touch

any property where the owner had remained. These men were carrying the Free

State flag, and this part of Natal is now spoken of as the Free State. No one in the

neighbourhood of Underberg has been interfered with, our friends are all safe, their

property also. It may seem like boasting, but indeed it is not, I am humbled while

uplifted to think how God has let my influence work for good, my deciding to stay

here decided our few neighbours to do the same. I have more at stake than anyone

10 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

else here, if 1 could risk my life by staying, they could too, so they reasoned, and the

result has been that not one home has been touched not a head of cattle taken.

Tuesday [October1 17th. The very air seemed full of unrest and excitement,

numbers of Boers going to Ladysmith came in during the day. We were feeling so

keenly about Dick that I think rumours failed to touch us, as they otherwise would

have done; I had to keep quiet and calm, for Kitty's sake, she was ill for a few days

with fear and excitement and the trouble about Dick. I was most anxious about her. 1

thank God that she has recovered and has been well and braver ever since. That

night I could not get to sleep for long, it must have been about three o'clock when I

did so, and was awakened five o'clock by a slight noise of doors opening and

shutting. At once I guessed the Boers were passing down, and that Lillie and Mr

Fraser were about. I would not move for fear of rousing Kittywee. In a little while

Lillie stole quietly into my room to tell me that it was so. Mr Fraser was first to hear

the noise and was up quickly and tapped at Lillie' s window as before arranged, she

went on to the verandah and they watched them for two and a half hours. They were

not going in army order, in twos and threes, and at times quite an interval, then

came a great many guns and waggons. Aftenvards we were told the first passed

about one o'clock and the last at five o'clock. It was a little starlight, the

figures could just be seen.

The talk was that Ladysmith was to be attacked in a few days, and they were

certain of succeeding, that is six weeks ago, and Ladysmith is still occupied by the

English.

The next days, [October] 18th! 19th120th were full of excitement, the ambulance

waggons and staff passed down; outspanned not far away, the men came in to buy

and we were very busy in the store, rain was falling and they all seemed very

miserable. The ambulance staff largely consisted of Englishmen, \vho had

volunteered for this work. rather than be commandeered to fight. Reports were

brought in of a few skirmishes - of course we could only hear the Dutch side, and

they invariably report one killed on their side and two/three wounded. So this week

passed on: our hearts were heavy for Dick, the girls and I drew very closely together

in this trouble and sorrow, and we were wonderfully strengthened: precious words of

comfort were brought home to our hearts. On Saturday 21 st a company of 80 armed

Boers passed down, followed by six waggons, containing food and ammunition,

nearly all came to the store and bought. I had no other thought then, but that they

would demand what they wanted, and go off with it, but they paid for everything

and were quite civil.

11 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

Thursday 24th. The thought of Dick in prison was much in our hearts, and the

thought of an appeal to the General had been in my thoughts some days: at last I

spoke of it and the others thought ,ve might try, though the hope of success was

small. I wrote out an appeal that morning, explaining how Dick was taken to their

Laager, and pleaded that in justice he might be released. My letter was approved of

by alL and 1 had not finished it ten minutes when an opportunity of sending it

offered it did seem providential. We waited five days then came a reply in Dutch,

how excited we were, while it was being translated. It was to say: The General could

not grant my request as to releasing Mr Sansbury, but he assured me of his safety,

also that he had given orders for my horses to be sent back. We ,vere sadly

disappointed and it was a fresh trial to our faith. In a day or two our spirits revived

and the girls and I clung to God's promises of help and deliverance, so the days

passed. We were very busy in our store. Boers were continually up and down and

came in to buy.

Sunday lOctoberJ 29th was a quiet day. In the afternoon some of our neighbours

came and 'the war' was the one topic of conversation. A report came that Mr Bloy

and one son were shot but as it \vas said they 'were shot in the fight at Elandslaagte.

,ve would not believe it. They would not be in the fight not anywhere near it we

have neither heard it confirmed or contradicted since. The Boers ,vould like it to be

true! How' little we ever thought our beautiful little colony of Natal would be the

scene of such horrors as are now being enacted in it. The homes made with such

toiL costing many years of hard work. almost ruined not much besides the walls

standing, doors and windows broken and the wood used for fire,vood furniture

smashed to pieces. organs, pianos. many expensive instruments deliberately

chopped to pieces. beds and mattresses cut open. and strewn round the houses. In

several instances the people had got up from a meal. the things being left on the

table. all their wearing apparel left. this was torn to pieces and scattered about.

On Nov. 2nd my horses were returned to me, also my keys. Dick had the keys of

the safe in his pocket and we had not been able to get at the books or cash box. Both

horses and keys were sent by a responsible man. and I was asked to sign a paper

saying I had received them. I did feel very thankful and somehow. the horses

com.ing back increased our faith that in good time Dick \vould be restored to us.

The fight at Dundee had taken place by now. Reports came to us very often just

then, and from them we could gather that the Dutch were not so successful as they

expected to be, but they boasted much of the number killed on the English side. and

the few on their own. From a Free State paper we heard that our soldiers did well. It

was talked of by a few leaning towards the English as a victory, but we knew that

they retired to Ladysmith. Whether this was necessary, or part of the plan we knew

not. We grieved to learn that General Pen (sic) Symons

ll

,vas killed in this figllt.

Now every day the Boers coming into the store would remark that they were going

to take Ladysm.ith tomorrow, later on they said 'next week.'

Nov. 3rd. We could hear the big guns quite distinctly. In the afternoon a number

of Boers came down from the Laager, also more waggons, and outspanned just

12 Catherine Portsmouth '."; letter

above us. to the left Cousin Harry Smith will know the spot I refer to. They came

and as usual were going to take Ladysmith. We are told what would be laughable

tales. if it did not touch what is so real and terrible. One day it would be that the

soldiers could not possibly hold out much longer, they were starving, and that they

were tired of it all, then that they were trying to make terms with 10ubert for peace,

anything to get out of Ladysmith. I wonder, did they really think we believed all

this?

9th. I am sitting at our evening meal when footsteps were heard round the

verandah, and a gentleman looked in at the open window asking, 'Is Mrs

Portsmouth here?' It was Dr Wilson

12

of Harrismith. 'We are an ambulance party,

may we put our waggonettes inside your yard for the night?' It was quite pleasant to

hear an English voice. He had two others with him. We invited them to dine with

us, this they gladly accepted. They had been having a very rough time, and enjoyed

the comforts of a spread table once more. The Boers were suspicious of Dr Wilson

and would not have him to attend to them, so he had orders to return to Harrismith,

and his helpers with him. One of these was a young fellow from Parker, Wood &

CO.

13

, Harrismith. In conversation I found they were allowed business

communication with their Vrede firm. so I asked him if he could manage to let my

sister know we were safe here, and he willingly undertook to do so. It was not safe

for him to take a letter from me to forward he migllt be searched, and such a letter

would lead to suspicion. I do hope the message reached Lizzie, but of course there

has been no means of hearing from her, thougll I have since heard. We had been

hoping very much that Dick would be allowed some liberty, but from these friends we

found he was not. This was an increased sorrow to us, our faith has indeed been tried.

10th. For the first time a Dutchman who was in the store expressed a doubt as to

their being able to take Ladysmith. Also at this time we heard good reports of the

work our troops were doing. During these days a great many troops of horses, cattle

and goats and sheep passed. these the Boers had looted, and they continue to do this.

finding Ladysmith more difficult than they expected. Some of the men were ordered

to go dmvn towards Colenso, the numbers has (sic) varied from 2 000 up to 5 000,

they have gone even beyond Colenso. Before this the capture of the Gloucester

Regiment was reported and this was all too true. We cannot hear full particulars,

but we know there must have been some gross blunder for a whole regiment to be

captured the Boers \vere greatly elated at tIns. After much thought I decided, with

the approval of all in the home, to try a second appeal to the General on Dick's

behalf. I wrote it out and to make it more sure of the General reading it himself, got

Mr van der Leeuw to translate it into Dutch. I copied it, we decided it was best the

appeal should go direct from me, not througll any medium. We waited an

opportunity of sending it, not one occurred for a few days, then a more respectable

Dutchman than many was in the stores, and Mr Fraser gave him the letter to hand

over to the General then in charge at Van Reenen, with a request that he would

forward it to General Prinsloo14

On Friday the 17th [November] the Boers moved from Van Reenen to near

Ladysmith, I should rather say the Laager, there were not many men left up there,

about 60 went down and 95 waggons. They all outspanned in the same place I have

before mentioned. What a lot it looked, and all was hurry and excitement, we did a

13 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

lot of business that day, mostly in clothes, for we had already sold out of much in

the grocery way. Dick had kept the stock up to about its usual amount, we had not

felt it wise to go in for anything extra, for no one knew if it would be taken from us

or not. We could have done double the business, had we had the goods, but I do not

regret this. I feel sure our reasons then were right though now we have scarcely

anything left to sell. We sent word to our neighbours that they must get a supply of

necessities at once if they wished to for if the goods were in the store, we should

not dare to refuse to sell to the Boers when they came in to buy. So for a while yet,

we in this neighbourhood have necessaries, but I will now finish this day. Mr Byloo,

Fraser and Smith were kept busy as possible the whole day, the young Boers walked

round the verandah into the garden [and] helped themselves to fruit. Fortunately it

was nearly all green just then, we had just cleared a tree of the most beautiful plums.

They were all carrying guns, but they were quite civil. expressed some surprise that

we had not gone away, and wondered what kind of people we were not to have done so.

On this Saturday the 18th 65 more waggons came down, they went on beyond

the Pretorius' to outspan. Sunday 19th was a quiet day, Mr Fraser. Lillie and Katie

went for a walk in the morning. Essie and Mr Smith were up in the garden amongst

the pines. and I was in the house alone, when an armed Boer, as I thought, came

round the verandah, I confessed to a little fear, being all alone. I went to the door

and spoke to him and he answered in English. He said he did not want anything,

only he was so surprised to find the house occupied, that he called to see who lived

here. He said all the houses lower down are empty, and the Boers have destroyed

everything, what could not be taken away they have broken to pieces, it is sad to see,

he added. Then he told me he was an Englishman, had lived in Heilbron 14 years

and so was commandeered. He had leave of absence for 14 days and was going

home - fighting against his own countrymen - I listened to his conversation but

said very little, it would have been unwise, thOUgll I believe his sympathies were

with the English. He stayed and rested quite a long time, I got him some tea and the

others all came back before he left.

Monday passed as usual. we were told that Lizzie' s husband was commandeered,

and was with the Vrede commando near Ladysmith. I felt troubled, yet hoped it was

not correct.

22nd. A red letter day indeed. Just after dinner. about two 0' clock. Mr Fraser

came to me saying, 'there is a man from Vrede who knows Mr Povall in the store,

will you not come and speak to himT I went and found 1\\"0 there, a Dutchman, an

old gentleman whom I had met at Lizzie' s, and an Englishman. They had both seen

Herbert and Lizzie a few days previously, and they were all well. Herbert had not

been sent to the front, how thankful I was. These gentlemen were only going to the

front to have a look, and offered on their return to take a letter for me to 111y sister.

14 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

They returned in ten days' time and I sent a few lines by them. I think they would

take it safely.

A little later I was resting in my room when I heard Mr Fraser open the passage

door very knock loudly at the girls' door and call, 'come quickly here is

someone coming you will like to see.' I heard Lillie' s voice at once, . Dick, Dick.'

You may be sure we were all together pretty quickly, Dick was off his horse and in

the house before Essie and I had time to run out and meet him. Oh what a meeting it

was! I must leave you to picture our delight and the thankfulness. How much there

was to tell as soon as Dick's escort, three armed Boers, had gone. We gathered in

the dining room to hear and to tell, Dick did not know at all why he had been

released, a telegram from the General to the Landdrost came on Sunday to say,

'Sansbury was to be released, and a safe escort given him to Underberg.' It was too

late to leave Harrismith that day, the train had gone (the Dutch are running the train

they took on October the 11th from the Natal Government, as far down as they can),

so he went to see the friends who had been so good to him all those five weeks, and

left on Wednesday for home, when he arrrived about three o'clock. He was looking

so well. we had not dared to hope this. Three lady friends, after much trouble and

perseverance, obtained permission to send him in food three times a day, and they

just fed him up, also they got in many little comforts which helped him wonderfully.

When we told about the appeal sent to General Prinsloo, Dick was sure it was that

that had been the means of his release. we are all very thankful.

Dec. 20th. I have not written anything of late, there is not much to write, unless I

put down the tales the Boers bring of their success, but these have not been much of

late. they have pretty well given up the idea of taking Ladysmith, but on Sunday the

17th we had a terrible report. Of course we only hear the Dutch version, and

knowing how they exaggerate, how little truth there ever is in the nWllber they give.

we try to hope it is not so bad.

On Friday the Boers entrapped the troops at Colenso, they say the English had

been firing with their cannon for three days and the Boers did not reply, so the

troops thOUgllt they had gone from the hill. and prepared to pass through the drift.

But the Boers had been working nights and had dug trenches and were in hiding, so

were already (sic) to fire upon the troops. They report that over 2 000 of our men

were killed, 150 prisoners with ammunition. They never tell of the killed and

wounded on their own side, though the man who told this story did say there were

60 Dutch killed and a great number wounded. We have felt so sad and yet we hope

the number killed is incorrect, we never doubt the ultimate result, but Oh! it does

seem as though it would be a long time yet, and the loss of life is terrible, and the

desolate homes and hearts.

Only four days to Xmas Day, is there any hope of the usual happy meeting with

our dear ones (note the numbers killed were greatly exaggerated, we are told not

more that 168). We must be patient and wait till all is over to hear the truth.

Jan. 14th 1900. You see dear friends it is some time since I have added to my

journal. I had not the heart to write through Xmas time and New Year. There was

15 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

no happy meeting and my dear boys are still far away, and I can get no news of

them, but I hope they had news of us about that time, and they would be cheered.

Through a friend we got a letter sent to Mrs Loze at Delagoa Bay and she sent it to

all our dear ones in Durban and Maritzburg telling them we were safe. We received

a post card from her on New Year's day, also a letter from Lizzie. It seemed a good

omen for the Ne,,,, Year, they were the first letters for three months.

The Boers attacked Ladysmith in the early morning of Saturday 6th [but] were

repelled with heavy losses, many whom we knew personally were killed, we hear

too, that the British troops are making preparations to cross the Tugela, it scarcely

seems worth writing these things. You will hear in England all about it, and we, so

much nearer, are shut off from all reliable information, but we have so many

mercies left to us, our comfortable home and the daily routine of duties keeping us

busy and occupied, and each trying to help one another, the burden of care and

anxiety is lightened for each one. We are all separated from some dear ones and

have sympathy one for another.

Jan. 28th [1900]. The weeks pass, still we are shut off from the means of

communication, I think of you all often and often. You will be troubled at the long

weeks of silence, and we too are troubled and find the long waiting a heavy strain

upon us, at times I have felt discouraged and an.xious, our provisions are getting

low, we have fruit and vegetables in abundance, and for a while yet we have flour,

sugar. tea and other small necessaries. Paraffin, candles and matches we have to use

with care, our neigllbours are not quite so well off. The Macfarlanes begged for a

little sugar as they were quite out; Mrs van der Leeuw for a little tea, Mrs Pretorius

for candles, which I had to refuse, and just as I sat down to my writing a kaffir, an

old kitchen boy of mine, came begging for a little paraffin, he has a sick child, and

had to sit up at nigllt with him. I gave it, how could I refuse, when I had it, but we

may be without ourselves ere long. Yet with all this, let me not forget God's mercies

which are so many, and great. Our daily needs have been supplied with all the quiet

and comfort this dear home can give. Most of us are brave and hopeful, and

deliverance is surely not far off.

On the 17th our troops came across the Tugela and we hear of heavy fighting

and heavy losses on both sides, for a week the cannons were going the whole day

from early morning till dark, they are fighting in two places, and from both we can

hear the guns. We have so hoped they would get throUgll to Ladysmith this past

week but fear it is not so. for two days no news has reached us, the cannons are quiet,

they may be fighting the small guns, if so of course, that means they are close together.

March 2nd. You see how long it is since I have written anything in my journal. I

had no heart to do so, and then to hear no news of my boys took much of my

courage away. I was afraid too. that I might write in a way that would pain you as

you read. And now what we have been waiting for so long has come. Yesterday

16 Catherine Port.'TllOuth ',,' letter

morning very early the glad news of the release of Ladysmith was brought to us. Oh!

with what thankful hearts we received it. 1 am going to look up my diary, and go on

from where I left off.

Jan. 28th. After the week of heavy fighting we heard our troops had retired, and

with this we had to be content all was quiet, no guns going and we did not know

\vhat to think, yet did not lose our faith in our brave soldiers. but oh, it was a time of

waiting.

On the 17th [February I we heard the good news that the troops had released

Kimberley, we rejoiced then. For a few days we had various reports of the troops at

Colenso, that they were advancing, that the Boers had been driven out of some of

their good positions. then we heard that they (our troops) intended being in

Ladysmith on the 28th. we waited in hope and fear. Then early Wednesday morning

the 1st March, the news was brought to us that Ladysmith was relieved. some of the

troops had got in the previous afternoon. Can you imagine how we felt the intense

relief, the deep thankfulness, the joy. Oh! it was a glad time.

You will have read much of it all. long ere this. it must have been a terrible time

for our poor soldiers, and for the Boers. They had to fly and at once orders were

given for the Free State laagers to move back to Van Reenen, they got away in a

great hurry believing the soldiers were following them. We have had no news of the

ambulance men, many of whom are English. They said those in command had kept

the defeat of the Transvaal Boers quiet, that many of the Free State Boers did not

know of it did not know why the orders \vere given for the retreat and it was

even circulated amongst them that it was for 'change of air', as there were so many

fever patients.

Some men on horseback reached here by six o'clock, having ridden all night

such an exciting day we had, many off-saddled near by. and then a little later

waggons came along, and through the whole day this went on. Waggons, carts.

traps, cattle and horsemen. some passing on up the Berg, some outspanning for a

while. a great many came to the store and were quiet and civil, seemed to be rather

rejoicing in going back: than depressed because defeated. Many of the Dutch

fanners of NataL I should say the few who were left, also trekked out yesterday.

afraid of the soldiers. Mr and Mrs Pretorius also went out. We were sorry they did. it

is not at all likely they would have been interfered with, but they believe everything

bad of the English soldiers: and so were frightened. Today has been a repetition of

yesterday, only that the waggons had finished passing earlier than the previous day.

We do not know at all what is coming now: if the Boers intend making a stand on

the Berg or not, if troops are coming up here, or not. We hope and pray there will be

no fighting near us and that we will be able safely to get into Ladysmith in a day or

two to post letters and send telegrams, and hear of at least some of our dear ones, so

we are all busy writing.

17th..... Last Sunday evening we had an exciting and anxious time for a while.

Two of the Macfarlanes came in to tell us they had notice from the military to leave,

as they would be in range of the firing from both sides. Mr Macfarlane and his son

17 Catherine Portsmouth's letter

went to Ladysmith on the Friday, and George was sent home to tell the others and

get their goods packed. A waggon was to be sent for them the next night. We were

very troubled and expected a notice that we too must move. We had quite a sad

hOUL and came such a relief it ,vas like a message from God. Mr Fraser was also in

Ladysmith to get out letters, saw Mr Macfarlane in the street who told him that he

had been advised to move. Mr Fraser went at once to the authorities and inquired if

it was really necessary. told them how we were situated, and of our two invalids

l5

who could not be moved without great danger. They asked many questions as to why

I did not leave as others had done. Mr Fraser told them we had made the place

ourselves, that I loved it and knew that the only chance of saving it from being

ruined by the Boers was to stay in it, and the Boers had respected our trust in them,

and had not molested us in any way. Then Lord Dundonald

16

ordered a special

permit to be written out giving us permission to stay in our home through the

present crisis. It is not stated in the permit. but Mr Fraser was told the risk was our

own, but we had nothing to fear unless there was fighting on the Berg and any of

the Boer cannon struck the house. So once again ,ve are cast entirely upon God who

has done such great things for us in the past. Mr Fraser brought letters from our

friends and from my dearest boys, they are well and have had many kind friends,

who have given them pleasure, and thought of and cared for them.

Since this is Sunday [March 18th J we have had [ a] quiet and uneventful day

'''ithout any news, this evening we hope the boy17 will return from Ladysnrith ,,,ith letters.

23rd [March] Durban. You will wonder at the above address. I am here (at last)

with my own dearest boys; Kittywee and I arrived last night. It took me a long time

to decide that it was the right thing to do. the girls and Dick were quite urgent for

me to come a\\"ay and see my boys. I do trust this has been of God's guidance. they

all tried to make it easy for me. and were so sure that there was no cause to fear

an)11ring going wrong.

We left my loved home at half-past five in the morning, and reached Ladysmith

at half-past eleven. We met British patrol parties twelve miles down the road, and

then a large camp about 15 miles. The Ladysmith friends were delighted to see me

and Kittywee. The town is very desolate and dirty as yet, dry and barren [but] the

buildings are not greatly damaged. We left at ten the next morning. reaching

Durban at half-past nine. Willie looks well and so tall, he went up to Harry early

this morning and brought him down and he has stayed the whole day with us, he too

is well and has grown very much.

I cannot write of our meeting, but our hearts are full of thankfulness to God who

has given us the great joy of being together again. I have at times some fear for our

dear home at Underberg, but I do know something of the quiet rest God can give,

after such months of daily experience of his power to sustain and protect through

such dangers. Now dear ones alL this long story must close. With warm true love to

each dear one.

Ever yours lovingly and affectionately.

Katie Portsmouth.

18

Catherine Portsmouth ','I' letter

BIBLlOGR\I)HY

f)1L'tlOnarr of,\'Ollfh ,1fncan biography: Yol. 1 \Iatthinus Prinsloo: Vot 4 Douglas :VI B H Codlran.::,

WilIiam Pcrln Symons

Hawkins, Eliza Blandl';: The stot)' otHarnsflllth, 18-19-1920. (LadysmitJl, 1 n2)

lIolmd-::tl's map of Natal and Zululalld. (Joharull..'sburg,. 1(27)

},;mal 1 R95, I R99 (Pictennaritzburg,. 1894, I Rn)

Portsmouth. llcrlry: IIistoricalnotcs of H)fonL known originally as l'nderberg,. (Typeseript n,d,)

South Ajhcan who's who 1910 p.530

Spcnc,-,'c S 0'13: Bntlsh set/lers in Natal. 182-1 185-, volume 2, pp.I06 8. (Pietermaritzburg, 1(83)

FA j)le geskledems van f farrwmth. (Bloemti)nkin, 1(32)

TI/nes o(Xatal2 Dec. 1897 (obituary ofMrs Ilcnrictta Stranack)

I Ch_'orge Chapman whom Lilian was to marry after the war. In 1913 tJle widowed Chapman married

CatJ1crine Portsmouili.

2 PrL'Sumably the wife of William Scott, fanner and blacksmiili, whose address in ilie 1899 Natal

,.j lmanac app.;ars as 'Scols{on, Yan Scolston or Scottslown was onc ofilie bOf(k'f fanns.

3. J IJ :"Ieiring and J C Rosa were ili.; otlicials at customs in Harrismiili customs

union bL"I.WL'CI1 'atal and ilic OFS \\as in force, 1890-94,

4. Smith, a suff(''fer tt'om tuberculosis. later died at Il):ford.

5. Pn.. 'SlImably G. Byloo who appt.'ars in ilie IR99 Natal ,41manac as a ti.lffi1cr of '{ lndcrbL'fg. Van

'. I Iowever, from tJ1C text it he was working in tJ1e Portsmouilis' store.

6. Presumably Gemardus Philipplls Pretorius, of Good Hop.;, whose name in boili

t11'; I (:95 and 1899 Almanacs, 'lbL'fc was also a G P Pretorius '(A's son)' who is Jistcxl as a fanner of

Alant:: Dnll. a 1;lrn1 adjoining Wagtenheetres J.:op.

7. 'Ibis mll!>1 havt.' bedl ilie BOL'fS' ht?4ldquart.;rs inside tJ1e OFS border.

&. Francis Ridlard Dloy (l (:36 1(06) had a border The Reproach. Bloy was a man of irascible

temperamcrlL The vcry nami..'S ofhis fanns iliis besides The Reproach, he had

so ilirollgh iliat was not granted as much land as iliought himself entitled.

\\bd1 his died in 1905 h-.: attributed hi..'f d.;aili to tJ1e 'cold-blooded ,-,welty' and 'negli.X.'t' of ilie

Natal GowmmcrlL whidl only in 1903 comp-::tlsated tJlem for loss.;:.;, and in his opinion. vcry

inadUIuately. quok'S trom a Id-lcr he wrote to tJ1e Re:;ident Magistrate when rUIuired to fill

in hL'f deatJl notice.

9. '[be tnms,.:ript does not rL'Cord ilie day in Ol..tohcr !\1rs B10y left on !\10nday (9 Ol..tobt.'f) and Bloy ilie

tollO\ving day.

10. '01is giv.;:.; impression tJut B1oys' home \vas on 16 October. Bloy himself maintained

it was 13 Octob",'f, whim coincid",'S wiili Mrs PorL<;moutJ1's entry lInd-.:r ilie date 22 November. where

sht.' iliat Sansbury. Whdl arrL'Sl.;d hy tJle Boers on 14 OI..'tobL'f. was at fiTh1 mi!>1akcrl t()r

Bloys' son, whom iliey had shot at 'a days

11. Major-GL'11cral Sir \\'i11iam PL't1l1 SYl110ns 1&99). ilie command",'f of ilie British forct.'S at

Dundee.

12. Dr Edward Fitzgcrald Bannat!n..: Wilson (born I g59. Jjmcrick. Ireland). who had come to Souili

,\1rica in 18R3. After tJle war h.; was Harrisl11itJl'S district surgL'on.

I]. Parkcr. Wood & Co. was a Durban tintl WitJ1 branmt!S in \lawl and beyond ilie Bcrg.

14. lbe OFS Chief Commandant, r-.lallhinus Prinsloo (1838-1903), He was mosru as sum once ilie

conmlandos of Harrismiili, Vre<.k Ikthkht?l11, Heilbron. Kroonstad and Winburg (a total of more ilian

6000 burghers) had mustered n.;ar Harrismit11. PrL'SlIInably iliis was at ilic 'I..aager' mentioned in ilie

15. One was r-.1r Smiili, 'The oilier could have Ik'l:.'1l Sansbury. It would seem iliat she died young.

16. Douglas M B H CodmlI1e, 12ili Earl of Dundonald (1852 1935). As commander of seL'Ond

Cavalry Brigade. he spear-headed tJ1C tinal drive towards Ladysmiili.

17. i.e. her Aific.'1n servant.

SHELAGH SPENCER

Vasco da Gama and the

naming ofNatal

Introduction

Five hundred years ago probably on 8 July 1497- four ships set sail from Lisbon

on a voyage that would prove to be of profound importance. The fleet was under the

command of Vasco da Gama, and the objective set for him by the King, D. Manuel

L was to complete a long saga of exploration along the Mrican coast undertaken by

Portuguese mariners in search of a sea route to India. Bartolomeu Dias had arrived

at the southern end of Mrica and ascertained its latitude during his voyage of 1487

1488. He also had seen that the coastline beyond Algoa Bay extended away to the

north-east. The long-sought entl)' into the Indian Ocean had at last been discovered

a spectacular feat by the small nation of Portugal.

By the time of Vasco da Gama's voyage, Portuguese investigations had greatly

improved knowledge of the wind and current systems in the Atlantic, and he was

able to take a route not previously tried

l

. He sailed to the western side of the South

Atlantic, tllereby avoiding difficulties always faced by ships trying to go against the

south-east trade winds along the West Mrican coast. Cautiously seeking the Cape of

Good Hope from the west. the fleet finally sighted land on 4 November, and

anchored three days later in what is today called St He1ena Bay.

There a meeting of contrasting cultures occurred. The local community appeared

and barter was attempted by the Portuguese, but spices and gold were unknown to

those hunter-gatherers. On 16 November, the fleet departed and rounded the Cape

Peninsula on the 22nd, only after several attempts frustrated by contrary winds.

They reached the bay of Silo Bras (Mossel Bay) on the 25th, and anchored there for

13 days. Bartolomeu Dias had been there before them, and it was a known source of

fresh water. The local people had cattle and sheep, and Vasco da Gama's men

succeeded in bartering for an ox. Unfortunately, both visits to Mossel Bay ended

badly, marred each time by misunderstandings and mutual hostility between

Mricans and Europeans. The ships left on 8 December, heading eastwards towards

Algoa Bay and the furthest point reached by Dias.

It is the next part of the voyage, during the remainder of December, that is the

topic of this study. The celebration of Christmas Day in 1497 by Vasco da Gama

and his crews as they sailed up the south-eastern coast led to the land known today

as Natal acquiring that name in commemoration of the Nativity. This is a very

familiar story, now part of folklore. It has been told in numerous popular histories,

Natalia 27, (1997), B. Stuckenbergpp. 1929

20 f,asco da Gama and the naming ofXatal

repeated in formal academic works, and even been an inspiration to poets::!. But no

less distinguished an authority on the history of Portuguese exploration in Southern

Mrica than Professor Eric Axelson has stated in several of his major writings. that

this attribution of the name was a mistake. He declared that the fleet was much

further south on 25 December. actually near Port St lohns. How did he arrive at this

conclusion. and was he correct?

The voyage during December 1497

Only one first-hand account exists today of the voyage of Vasco da Gama during

1497-1499. Although anonymous. its author has been identified as Alvaro Velho,

who was aboard the Sao Rafael.

3

The first English translation of this was by E. G.

Ravenstein in 1898.

4

Another translation was published by Axelson in 1954. in his

book South African Explorers. He republished it with extensive conunentary in

Dias and his successors.6 a book issued in 1988 to commemorate the voyage of

Bartolomeu Dias.

The following record of progress by the fleet during December. and quotations

from Velho' s account are taken from Axelson' s translation.

25 November (Saturday): arrived in Mossel Bay.

7 December (Thursday): attempted departure from Mossel Bay thwarted by lack

of\vind.

8 December (Friday): departed from Mossel Bay.

15 December (Friday): passed Ilheus Chaos (Bird Islands) in Algoa Bay.

16 December (Saturday): passed Kwaaihoek where Bartolomeu Dias had erected

his last padrao, reached Rio de Infante (Keiskamma River) and lay to during the

nigllt.

17 December (Sunday): continued along the coast wind astern, until evening.

when the wind changed to the east and the fleet had to tack out to sea.

18 December (Monday): at sea in unfavourable conditions.

19 December (Tuesday): near sunset the wind changed to the west: the fleet lay

to overnight so that the land could be reconnoitred the next day to establish their

whereabouts.

20 December (Wednesday): went landwards, and found themselves off llheu da

Cruz (St Croix Islands) in Algoa Bay: the ships resunled their original course' ...

with a very strong stern wind which lasted three or four days ... From that day

onwards it pleased God in his mercy for us to make progress and not retrogress.'

25 December (Monday): 'On Christmas Day ... we had discovered 70 leagues of

coast.'

The point at issue concerns the distance of 70 leagues attained by Christmas

Day. In determining where they might have been, two questions of critical

importance need to be answered: what distance was represented by the measurement

of 70 leagues, and from what starting point had it been measured? Concerning the

second question, Axelson

7

was surely correct in interpreting the phrase '... we had

discovered' to mean that the fleet had passed a length of coast new to Portuguese

exploration, i.e. beyond the furthest point reached by Bartolomeu Dias, namely the

Keiskamma River.

21

Vasca da Gama and the naming afNatal

..:.j

I

Cape St LUCira

. I

o 100 200 300

....;. ....)

1 I . ',' ()

km (approx.) :: /J

...; 1

h

-;l

Durban::.::',:'

... :.. (

':::/

:-.:' / /

Port

. / '" I

..... )/: .... //,( 14 .

.. "

... /

.

.. : ....... /')(

East . ... /i /

:.: / ,

/

;

/

,.r

.....

Fig. 1. The average course of the Agulhas Current. shown by the heavy line. wIth bars denotmg

standard deviations at eight sites listed in Table 1. (Atter Grundlingh. J983.)

22 vasco da Gama and the naming ofNatal

The distance of '70 leagues'

Axelson first took up the question of the distance sailed during 20-25 December in

his book South-East Ajrica 1488-1530.

8

He made the following statement:

Assuming Dias' s farthest to have been the Keiskanuna, da Gama had on

December 25 reached the Umtwalumi River. Seventy leagues from the Kowie,

however. \vould have taken him to the Umtamvuna. Seventy leagues from the

site of the last padrdo of Dias would have taken him to a few miles north of

Port GrosvenoL Apart from the consideration that 70 is a round figure, it is

impossible to resist the conclusion that it was an exaggeration. The daily run

from Mossel Bay to the Infante averaged only 32 or 33 miles a day. whilst if the

four or five days wasted in the vicinity of Bird Islands be included, the run

drops to the region of 23. It is unreasonable to suppose that the 240 miles from

the Infante northwards, along a coast where the Agulhas current runs if

an)1hing more strongly, could be covered at an average of 55 miles a day:

except with the assistance of a stronger wind lasting longer than was described

in the Roteiro.

In 1973, he returned to this topic in Portuguese in South-//ast Ajrica 1488

1600.

9

\vith these words: 'On Christmas Day the pilots calculated that the

expedition had discovered 70 leagues, so a section of the Transkei coast received the

name Natal. Three days later the mariners caught fish off what was probably the

Durban bluff.' To this statement he attached the following footnote: I I) '70 leagues,

168 miles, from the Keiskamma river would have taken the squadron to the vicinity

of Waterfall Bluff. 18 miles north of Port St Johus.' For this calculation, a league

was taken to be 6.66 km. There seems to be an error of arithmetic here, or perhaps a

lapsus calami: 70 leagues would in fact be about 466 km (289 miles, or 252 nautical

miles): the distance from the Keiskamma River to Port St lohns is much less

about 280 km (174 miles). If about 466 km had been 'discovered', the fleet would

have been somewhere between present-day Scottburgh and Umkomaas.

In Dias and hi.)" successors,]] Axelson recalculated 70 leagues at 5.92 km per

league,12 and he stated that the ships would have got to 20 miles beyond Port St

lohns if indeed they had covered 70 leagues. He wrote: .... it is difficult to believe

that in five days. even with a strong stern wind the ships could have made good 266

miles against the Agulhas current. and it is probable that they were in the vicinity of

Brazen Head fI8 km south of Port St lohns} on Christmas Day.' Here there appears

to be another inconsistency: 70 leagues at 5.92 km per league equals 414 km (257

miles. 223 nautical miles), a distance that would have placed the ships far beyond

Port St 10hns - in fact, north of the Mtam\una River (which is about 360 km from

the Keiskamma) and off the Natal South Coast

In these discussions of the progress of the fleet, an important point must not be

overlooked. There is no information on when the Keiskamma River was passed for

the s.econd time. so we cannot be sure of the time \vhen the distance of 70 leagues

would have been commenced. All we are told is that the ships left the St Croix

Islands on 20 December and had an uninterrupted jounley up the coast. An

assumption has to be made at this point as a basis for further discussion, and it is

this: that the fleet left the St Croix Islands at midday, and that the 70 leagues

23 Vasco da Gama and the naming a/Natal

'discovered' had been attained by midday on Christmas Day (it could be relevant

that latitude would have been determined by readings taken at midday). The

distance between the St Croix Islands and the Keiskamma River (c. 175 km) must

therefore be added to the 414 km represented by 70 leagues (total 589 km) in all

calculations.

Axelson's arguments thus revolve around two issues: first, he considers that the

ships would not have been able to maintain a rate of progress adequate to cover such

a distance in five days; and, second, that their progress would have been greatly

impeded by the Agulhas Current. Concerning the question of the speed of the ships,

an assessment depends considerably on whether the fleet sailed throughout that

period without interruption. Axelson 13 asserted that after passing the furthest point

reached by Dias and entering unexplored territory, ' ... it became customary when

possible to lie to during the nights.' But there is no clear evidence for this; Velho

records only that the fleet lay to on two occasions: on the night of 16 December

when they reached the Keiskamma River, and 19 December, after two days of

easterly wind when the ships had to tack out to sea and lost sight of land.

If sailing continued day and night without interruption, during five 24-hour

periods from midday on 20 December to midday on 25 December, then the fleet

would have covered 589 km in 120 hours; thus they would have sailed at 4.9 kph or

2.65 knots. That would have been an extremely slow average speed, within

the capacity of caravels, and unlikely in view of ' ... the very strong stem wind which

lasted for three or four days.' Such slowness would require an explanation. If,

however, the ships lay to at night, they would have still had at least 14 hours of light

daily in which to sail, and thus a hypothetical total of 56 hours over the five days.

Average speed would then have been 8.4 kph or 4.5 knots, probably within the

capacity of caravels.

14

Assistance from counter-currents going up the coast could

also have been in their favour, which is discussed below. Perhaps sailing continued

at night when there was a moon or enough light to make it safe.

Axelson15 compared the run beyond Algoa Bay to the journey from Mossel Bay

to the Keiskamma River, for which he estimated a daily average of 32 or 33 miles. If

sailing continued throughout the night, the fleet would have averaged 2.21 kph or

1.19 knots. Certainly that would have been extraordinarily slow, but there was ' ... a

great tempest' on 12 December, and the ships had to run with the wind astern under

' ... greatly lowered foresail' in an unspecified direction. Velho does not tell us how

long the gale lasted. Their progress may also have been slowed by westward

meanders from the Agulhas Current moving across the Agulhas Bank. The

comparison thus has dubious validity.

Another matter needs to be considered: how was the distance of 70 leagues

measured? During the eastward voyage from the Cape of Good Hope, only dead

reckoning by the use of compass, log-line and sand-glass was possible. Once the

fleet was past Algoa Bay and proceeding north-eastwards, measurements of latitude

by the cross-staff or the mariner's astrolabe

l6

would also have been possible. Velho

records no latitudes, but they must have been measured as the journey progressed.

Velho did, however, give estimates of distances of various legs of the journey.

Axelson

l7

compared these with his own measurements, as follows:

24 Vasco da Gama and the naming o/Natal

Velho ~ ~ ~ (footnote)

St Croix Bird Islands 5 leagues 7.8 leagues (no. 27)

Mossel Bay St Croix 60 leagues 68 leagues (no. 28)

Cape Good Hope - Mossel Bay 60 leagues 67 leagues (no. 29)

Bird Islands K waaihoek 5 leagues 5.7 leagues (no. 30)

K waaihoek Keiskamma River 15 leagues 15 leagues (no. 3 1 )

In no case was there an overestimation by the Portuguese: all distances except the

last are underestimates, possibly due to technical imperfections in their method of

dead reckoning. The last estimate was almost correct according to Axelson (he

found it to be only 2 miles short of the Keiskamma River); it was the only one that

could have been made through readings of latitude. Axelson' s opinion that 70

leagues ' ... was an exaggeration' thus seems unjustified. There is, however, a

questionable tendency to record distances in round figures or in multiples of five.

We can conclude only that the distance of 70 leagues was measured in some way,

and that it may have been an underestimate.

The Agulhas Current

There is no evidence that the average speed of Da Gama' s ships was such that a

voyage of 70 leagues (say 223 nautical miles) could not have been accomplished in

five days, even if the distance from the St Croix Islands is added. The discussion

shifts therefore to the question of whether the Agulhas Current would so have

impeded the ships that such a distance could not have been achieved. Axelson cited

this as a conclusive factor in each of his discussions of the topic.

A brief description of the Agulhas Current was given by Axelson.18 In the

following account, I have taken information and quote freely from excellent

publications by Dr Marten Griindlingh19 and Dr E. H. Schumann.

20

In the southern hemisphere, currents are intense on the western side of the ocean

basins as a result of anticlockwise gyres driven by the m ~ o r wind belts, which are

reinforced by the Coriolis Force created by the rotation of the earth. In the South

Indian Ocean, these forces combine to produce the Agulhas Current (Fig. I) along

the east coast of South Africa, ' ... one of the strongest currents of the world's

oceans. ,21 It forms off northern KwaZulu-Natal, through the confluence of waters

from the western side of the Mo<;ambique Channel and from the South Equatorial

Current going westwards around the southern end of Madagascar. The current takes

the form of a well-defined, intense central core or jet. For most of the time it flows

offshore of the 200m isobath, following the continental slope all the way in a

smooth, quasi -linear fashion, with a sideways meandering displacement of 10-15

km on either side.

22

The core has a width of some tens of kilometres, and with

current velocities on either side being considerable in parallel to the core, the overall

width can be up to 100 km (off Durban. for instance).

Fig. 1, modified from a map by Dr Griindlingh,23 shows clearly the average

course of the core, together with bars expressing standard deviations of averages at

eight sites. Data relating to this map are given in Table 1 (from Griindlingh24).

25 Vasco da Gama and the naming ofNatal

Table 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Latitude 2815' 29"'15' 3020' 31"03' 3130' 3230' 3315' 3345'

Core distance

offshore (km) 29 58 43 30 43 35 50 69

Standard deviation 14 9 19 6 16 15 9 6

Bottom depth at

intersection (m) 1100 500 2400 2300 2200 1300 2200 1900

The map and table show that the core, and hence the full strength of the current,

during 77% of the time would be found offshore of the 200m isobath, with current

force diminishing landwards as the seabed rises. The map also makes it clear that

the largest standard deviation (where the current wanders most) is in the vicinity of

Durban. The smallest standard deviations occur off Port Edward and off Port

Elizabeth where the rise of the Agulhas Bank deflects the current offshore. In

coastal waters the current normally has little or no effect. It would have been

possible for the fleet to avoid its effects by sailing along the 25m isobath all the way

from Algoa Bay to Durban, a course \vith no obstacles in the way.25

Coastal or shelf currents occur in the inshore waters, and may constitute

northward flows referred to as counter-currents. They are often apparent in the

summer when discoloured water entering the sea from rivers is visibly moved

northwards along the coast. When westerly winds blow, the Agulhas Current moves

further offshore, and the counter-currents then increase and speed up.

The only encounter with a current recorded by Velho along the south-eastern

coast started on 17 December, after the ships had passed the Keiskamma River. The

wind changed to the east, and the fleet tacked out to sea to avoid the dangers of a lee

shore, until close to sunset on the 19th, when the wind turned again to the west.

They lay to that night, adrift, and the next day went landwards to find out where

they were: ' ... to their amazemenC

26

they found themselves back in Algoa Bay near

the St Croix Islands. A strong westerly wind then ' ... enabled us to overcome the

currents.' In tacking out to sea, Da Gama' s ships probably encountered the inshore

flank of the Agulhas Current in the region where the core normally lies about 50 km

offshore (Locality 7 in Fig. 1). A strong easterly wind of the sort they experienced

often moves the current shorewards. This encounter clearly created a great

impression. Camoens conveyed it well:

F or many days our gallant vessels ride

Through calm and stormy waves alternately,

With t1uctuating hope our only guide

We opened up new paths across the sea.

And then, it seemed all progress was denied.

The ocean, changing mood inconstantly,

Despatched a current of such weight and force

We made no headway in our northern course.

26 Vasco da Gama and the naming ofNatal

From this same retardation you may guess

How powerful that current, how extreme.

The force of wind which favoured us was less

Than the head-on opposition of that stream.

Then Nolus, the old south-wester, in distress

At this deep challenge Neptune flung at him

Unleashed a furious rage that blew us free

In airy triumph 0' er the stubborn sea. 27

The Agulhas Current certainly had the potential to be a serious impediment, but

Axelson's view that Da Gama' s fleet tried to sail against it all the way along the

south-eastern coast is surely improbable. Having experienced the current so

dramatically, the mariners would have been alerted to its existence. The Portuguese

pilots in the Age of Discoveries attached great importance to 'nature's signs,28 as

aids to navigation. The roteiros they compiled contain information on what should

be looked for at various stages in the carreira da india. Clues such as the colour of

the sea, direction of the waves, the species of birds and direction of their flight, 29

presence of drifting seaweeds and of debris from large rivers, were important,

especially as no means existed then of measuring longitude. Experienced pilots

would quickly detect changes in the maritime environment.

It is pertinent to appreciate that the Agulhas Current is a very visible

phenomenon, presenting many signs of its presence. Its core water is a superb,

intense ink-blue colour, remarkably pellucid and quite unmistakable. In summer,

the core has a temperature of up to 28C., and so is perceptibly warmer than coastal

waters. For this reason the current shows conspicuously in images assembled by

heat receptors on the NOAA satellite (Fig. 2). Carried in the water are many

different organisms that proclaim its tropical origin: spectacular jellyfish pulsate on

their way; siphonophores, such as the violet-blue 'Portuguese man-o' -war'

(Physalia) buoyed by its float and Vel/ela with its vertical 'sail', populate the

surface; flying-fish scatter over the waves, and oceanic birds are about. The current

is also often marked by a line of towering clouds which can be seen from afar, for

example off Algoa Bay even though the current is well off shore there (Fig. 1 and

Table l)?O

With so much evidence of a powerful current, the fleet would prudently have

kept inshore. This would also have enabled them to monitor their progress better.

That they were at times close enough to see the land in considerable detail is proven

by the following passage by Velho,31 referring to their journey north of the

Keiskamma River:

As we coasted along two men began to run along the beach opposite us. This

land is very attractive and well situated; and we saw many cattle wandering

about on the land here; and the further we advanced the better did the land

become and the higher the groves oftrees.

27 Vasco da Gama and the naming ofNatal

Fig. 2. An image ofSouthern Africa recorded by the NOAA Satellite on the night of 10 October 199:,

It was compiled through measurements ofsurface temperatures. The warm sea ofJMozambique

can be seen extending into the Agulhas Current whose course is clearly apparent along the

south-eastern coast of South Africa. Recorded by RSMAS. University o.(Miami. and publicly

available on the 1nternet,

Conclusions

An indeterminate uncertainty surrounds all the calculations made above, and

assumptions had to be made. The validity of the results depends particularly on the

accuracy of Velho's record of 70 leagues: its correctness will never be known. but it

is inconceivable that incompetent or inexperienced pilots and captains would have

been chosen for such an important voyage. For the ships to have been south of the

Mtamvuna River at midday on Christmas Day, an unlikely overestimate - about

11 % of the distance sailed - would be required, or a misreading of latitude of at

least ~ o . It is more probable that the fleet was north of the Mtamvuna, even by 60

km or more, and thus off or past present -day Hibberdene.

In their History of Natal,32 Brookes and Webb take a light-hearted view of the

possibility that Vasco da Gama gave the name Natal to a part of the Pondoland

coast. They wrote: 'Since no one in Pondoland desires to be thought a Natalian, and

since after all the present Port Natal was discovered "within the Octave,,33 there

would seem to be no great harm in accepting Vasco da Gama's name as applying to

the present Province. It is doubtful how far Julius Caesar was right in using the

name "Britannia", but correct or incorrect Britain and Natal are alike accepted