Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Hedstrom

Transféré par

Bruno Carriço de AzevedoDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Hedstrom

Transféré par

Bruno Carriço de AzevedoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

European Sociological Review, Vol. 12 No.

2,127-146

127

Rational Choice, Empirical Research, and the Sociological Tradition

PeterHedstrim and'RichardSwedberg

In this article we argue that rational choice theory can play a progressive role in unifying theoretical and empirical work in sociology. The basis of rational choice theorizing is outlined, and it is argued that important ideas of Karl Popper, Max Wsber, and Robert K. Merton properly belong in this tradition. Three elements in rational choice theorizing are deemed particularly essential for explanatory sociological theory: the principle of methodological individualism, the analytical mode of theorizing, and the notion of intentional explanation. The article also contains a critique of variable-centred research for paying insufficient attention to the role of actions and intentions in generating the data being observed. Acceptable explanations should, in principle, always specify the mechanism(s) involved, and this usually requires direct references to the actions and interactions of individuals.

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

Introduction

Most sociologists would agree that one should always strive to establish a symbiotic relationship between theory and empirical research, where each contributes to the development of the other. But most sociologists are also aware of the fact that this ideal is far from being realized, and most sociologists would have difficulty in naming more than a small number of studies where this ideal has actually been realized. What is particularly disturbing about contemporary developments in sociology, however, is that the gap between theory development and empirical research appears to be widening. In the increasingly fine-grained intellectual division of labour among sociologists, 'the theorist' has become ever more separated from concrete research. This is particularly true for postmodernist sociology, where the attempt to explain something has been more or less replaced by the ambition to interpret social phenomena, but it is also common among more traditional theorists, such as Jeffrey Alexander (see e.g. the critique of this tendency in Boudon, 1995: 233; and, for a telling example, Alexander, 1988: 78-81).

O Oxford Unjytnity Vna 1996

Due to the dominance of this type of nonexplanatory discourse, sociological theory appears to have less and less bearing on empirical research. A similarly lopsided attempt to analyse empirical data without the guidance of any substantive theory (but in the form of a few stereotyped references to 'theory") is also prevalent today. Most empirical research carried out by sociologists concerns subject-matters guided more by the political and social issues of the day than by sociological theory. As a result, empirical research currently has Little or no bearing on the development of sociological theory. In this situation it becomes imperative to examine what role rational choice theory can play in unifying theoretical and empirical work in sociology. The position that we shall take in this paper is that rational choice theory can indeed play an important role in this enterprise by providing tools for the construction of explanatory middle-range theories with clearly specified empirical referents. Rational choice theory provides an action theory that is useful in many branches of sociology and, perhaps even more importantly, rational choice theory represents

128

PETER HEDSTROM AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

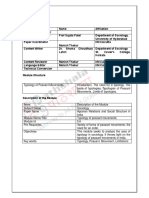

a type of theorizing that deserves to be emulated Actions more widely in sociology. This type of theorizing is amb/tical; it is founded upon the principle oi methodological individualism; and it seeks to provide causal cum intentional explanations of observed phenomena. Beliefs about possible Rational choice theory is often portrayed as being Interests action opportunities and alien to the sociological enterprise, and according their effects to many observers the rational actor assumption even represents a violation of a 'disciplinary taboo' (Baron and Hannan, 1994). This view of our intellecInformation tual heritage is not in accord with the historical record, however. The type of theorizing that rational choice theory represents is - contrary to current Figure 2. EJtmetts aj'defended mtimalcbokt explanations beliefs not a recent invention, but has a long tradition and an exceptionally rich sociological heritage to draw on. that actors, when faced with a choice between We shall devote special sections in this article to these points, while discussing the general relationship between rational choice theory and empirical research, and we will synthesize and extend previous arguments brought forward by rational choice sociologists.1 First, however, we shall present the core ingredients of rational choice explanations in order to lay the foundation for our argument. different courses of action, will choose the course of action that is best with respect to the actors interests. Recent scholarship in the rational choice tradition has brought the role of information into the foreground. If information is not perfect, as it rarely is in real-life situations, an actor will act on the basis of his or her beliefs about possible action opportunities and their effects. Individuals' beliefs and beliefformation processes have thus become important areas of rational choice theorizing, and individual actions should thus be seen as the results of three proximate causes: interests, beliefs, and opportunities (sec Figure 2).3 As Elster (1986) has emphasized, once we allow for imperfect information, the requirements for an action to be considered strictly rational become rather stringent. Not only must the action be optimal, given the actors beliefs about possible courses of action and their effects, but the beliefs themselves must also be optimal (or at least reasonable), given the currently available information. Finally the amount of information being collected must be reasonable given the actors interests and prior beliefs; to endlessly collect poindess information or to systematically ignore relevant information are, according to most accounts, obvious signs of irrational behaviour.4 In assessing the usefulness of this action theory it is essential to consider its role in the sociological enterprise. If it were intended as a psychological theory seeking to explain the behaviour of single individuals, its usefulness would be limited indeed.

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

The Basics of Rational Choice Theorizing

Rational choice theory is at its core a simple action theory that is deemed useful because it allows us to understand how aspects of a social situation can influence the choices and actions of individuals. O n the most fundamental level, a rational-choice explanation always invokes a model resembling the one in Figure 1. A rational choice explanation is characterized by the assumption diat an actor, when deciding which course of action to choose among those available in the actors opportunity set, always will choose the course of action that best satisfies the actors interests (see Elster, 1986; Hedstrom, forthcoming). 2 Rational choice theory is thus first and foremost an action theory predicting

Actions

Interests

Opportunities

Figure 1. Con dementsof'rationalchokeexplanations

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH, ANDTHE SOCIOIOGICAL TRADITION

129

Macro state or event atf = 1.

Macro state or event at t = 2.

Interests Beliefs Opportunities

Figure 3. Matro-Miov Imkagx atwrdbig to rational dxria theory

Individual Actions

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

But sociology is first and foremost a discipline concerned with the analysis of aggregate social systems and not the personalities of individual actors. Consequently, rational choice theory is not important to sociology as a behavioural theory of individual choice, but as an ideal-typical action mechanism in a theory of macro-level states or events. If we observe a relationship (represented by the dashed arrow in Figure 3) between two macro-level states or events (e.g. ascetic Protestantism and 'the capitalist spirit' or organizational characteristics and rates of mobility), we seek to make this correlation intelligible by explicating how the macro-state at time 1 influenced the interests, beliefs, and/or opportunities of individual actors; how these influenced individuals'choices of actions; and how these actions (and interactions) in turn generated a new macro-state at time 2. Rational choice theory proper only concerns the action mechanism which translates interests, beliefs, and opportunities into choice of action. The link between the context of action and the beliefs, interests, and opportunities of actors, as well as the link between individual actions and collective outcomes, are not part of rational choice theory as such. Many different situational and aggregation mechanisms are compatible with the assumption of rationally acting individuals. This type of approach to sociological theorizing is obviously extremely ambitious as compared to a traditional 'causal' approach, that simply classifies observed relationships at the macro-level without trying to establish a theoretical micro-foundation for the analysis. In order to accomplish this link

between different analytical levels, abstraction and simplification are obviously needed. The action mechanism of rational choice does not state what a concrete person would do in a concrete situation, but what a typical actor would do in a typical situation. It is our conviction that the use of this action mechanism will significantly improve sociologists' ability to analyse the core problem of sociology: how social structure constrains and enables social action by individual actors.

The Importance of Rational Choice for Sociology

Over and above the specifics of this action mechanism and its usefulness in situational analysis (which will be discussed more fully below), we wish to argue that the type of theorizing that rational choice theory represents should be emulated more widely in sociology. This type of theorizing is (1) analytical, (2) founded upon the principle of methodological individualism, and (3) seeks to provide intentional explanations of observed phenomena. The Primacy of the Analytical Rational choice theory represents a type of theorizing which is explicitly analytical. The theoretical analysis proceeds by first constructing an analytical model of the situation to be analysed (an 'ideal type'). This theoretical model is ideally constructed in such a way that it includes only those elements believed to be essential to the problem at hand. The target of the

130

PETER HEDSTRCM AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

theoretical analysis, then, is this model and not the reality which the model is intended to explain. However, to the extent that the theoretical model has been constructed in such a way that it incorporates the essential elements of the concrete situation, the results of the theoretical analysis will also shed light on the real world situation that the model is intended to explain. Or, as Schumpetcr (1908: 5278) once put it, when the tailor is good, the coat will fit. Much of sociological theorizing appears to be guided by a disbelief in the value of analytical abstractions and by a corresponding belief in the possibility of providing theoretical accounts of what happens as it actually happens. No one would dispute the attractiveness of this position if it were possible to realize, but accounting for something "as it actually happens' is always problematic, and is reminiscent of Ranked by now outdated and naive historicist position that history should always be analysed 'wie es eigentlich gewesen' (Ranke [1824] 1885: vi; for a different approach to the relationship between rational choice and history, sec Blossfeld's contribution to this issue). As argued by Mario Bungc (1967) among others, simply describing all the events, microscopic and macroscopic, that take place in a room during one second would if it were technically possible - take centuries, and this very fact is the main reason for the necessity of an analytical approach. Even in the most trivial description of a social situation, we are forced to be highly selective about which events to include and which events to exclude from the description; and this choice, implicitly or explicitly, is guided by our prior belief about the essential elements of the situation. Thus, even the most detailed descriptive accounts are alway 'models' of concrete social situations, and these descriptive models will always distort reality by accentuating certain aspects of the situation and ignoring others. An important implication of this, as emphasized by Gudmund Hernes (1979), is that the alternative to a specific model never can be no model at all, but is always an alternative model. Or in Hernert more colourful language, 'models are to social science what metaphors are to poetry - the very heart of the matter' (Hernes, 1979: 20). The distinction between a complex social reality and an intentionally simplified analytical model of

this reality seems to have been lost in many sociological discussions of rational choice theory. The standard sociological critique of rational choice theory focuses on the realism of its assumptions and views theories and theoretical assumptions as the equivalent of empirical hypotheses. Because rational choice theory is based upon simplified and therefore, strictly speaking, inaccurate assumptions, according to this view, it should be rejected like any other hypothesis that fails an empirical test. Criticism of this sort - which basically entails pointing out that theories which are intentionally built upon empirically inaccurate or incomplete assumptions, are indeed built upon empirically inaccurate or incomplete assumptions - is clearly redundant. Criticizing an analytical model for lack of realism is a common instance of the logical fallacy which consists in mistaking the abstract for the concrete what Whitehead ([1925] 1948:52) called 'The Fallacy of Misplaced Concreteness'. The choice between the infinitely many analytical models that can be used for describing and analysing a given social situation can never be guided by their truth value, because all models by their very nature distort the reality they are intended to describe. The choice must instead be guided by how useful the various analytical models are likely to be for the purpose at hand. Friedman (1953) presents the classic arguments against the notion that theory choice should be based on the accuracy of theoretical assumptions. As pointed out by Sen (1980) and others, Friedman overstates his case, however, and fails to make a distinction between descriptively foist statements and descriptively meompktt statements. While descriptive incompleteness appears to be a defining characteristic of all important theories, there are no inherent advantages in basing theories on descriptively false assumptions, as Friedman seems to imply.5 The failure of many sociologists to recognize that all theoretical work is based on implicit or explicit analytical models that by definition distort the reality they are intended to describe or explain, has generated many unproductive debates within the discipline. We believe that the infusion of rational choice theory into current sociology will increase the awareness of the distinction between the abstract and the concrete, and thereby contribute to the development of explanatory theory.

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH, ANDTHE SOCIOLOGICAL TRADITION

131

explained by the intended and unintended consequences of individuals' action. But faced with a The second aspect of rational choice theorizing world consisting of causal histories of nearly infinite that would contribute to better explanatory the- length, in practice we can only hope to provide ories, if emulated more widely, is, in our view, information on their most recent history.6 By taking the principle of methodological individualism. certain macro-level states as given and incorporatMethodological individualism is the doctrine that ing them into the explanation, the realism and the states that social phenomena are in principle only precision of the proposed explanation is greatly explicable in terms of individuals' actions (cf. improved. The principle behind such analyses, as Schumpctcr, 1908: 88-98). It is useful to distin- seen above in Figure 3, is to start with a given guish between a strong and a weak version of macro-structure, to examine how changes in this methodological individualism. The strong version structure are likely to alter the actions of the indiviof the doctrine only accepts 'rock-bottom' expla- duals populating the structure, and then to deduce nations, i.e. explanations that include no how these new patterns of behaviour are likely to references to aggregate social phenomena in the influence the same macro-structure at a later point explamms. The weak version of methodological in time. individualism takes the same ontological position The weak version of methodological individuas the strong version, but accepts for the sake of alism advocated here, and of which rational choice realism non-explained social phenomena as part theory is a sub-category, is in our view an essential of the explanation (see Udehn, 1987). methodological principle for the construction of Methodological Individualism While the search for rock-bottom explanations is often intellectually challenging and intriguing, it usually leads to stories of the state-of-nature type. These sorts of stories, in our view, are often of limited use since they ignore too many essential elements of the social situation. Legal rules, social institutions, productive capacities, and the like, arc often essential elements of sociological explanations, and are the results of long and intricate historical processes. As the philosopher David Lewis aptly put it: 'Any particular event that we might wish to explain stands at the end of a long and complicated causal history. We might imagine a world where causal histories are short and simple; but in the world as we know it, the only question is whether they are infinite or merely enormous' (Lewis, 1986: 214). From the perspective of the strong individualistic programme, these sorts of institutions must either be ignored and a world of short and simple causal histories be assumed, which to us seems unacceptable; or they must be endogenized, which, given the current state of social theory, seems unrealistic. For an empirical science like sociology, these types of state-of-nature stories are therefore likely to be of limited use. The weak version of methodological individualism agrees with the proponents of the strong version that all social institutions can, in principle, only be explanatory sociological theory. This type of theory should be sharply distinguished from theories that imply that structural outcomes can and should be explained directly in terms of structural causes, without giving any explicit attention to the role of human agency. Comparative crossnational research, for example, is an area of sociology where 'holistic* theorizing still seems to be fully accepted. \^udations in national policy outcomes are often explained with reference to other aggregate entities, such as 'policy regimes' (Esping-Andersen, 1990) and 'families of nations' (Castles, 1993), with only scant and post hoc attention given to possible micro-macro linkages. (For other influential examples of this type of theorizing, see Skocpolls (1979) theory of revolutions, Blau's (1977) theory of inequality and heterogeneity, and Hannan^ theory of organizational evolution (see Hannan and Carroll, 1992).) From the perspective of a methodological individualist, approaches that explain structural outcomes directly in terms of structural causes, are incomplete and therefore unsatisfactory. A proper understanding of the processes that generate macro-level change and variation entails showing how macro-states at one point in time influence the behaviour of individual actors, and how their actions add up to new macro-states at a later point in time.

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

132

PETER HEDSTRC-M AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

Intentional Explanations As suggested by Jon Elster (1983), the types of explanations used by social scientists are either causal, functional, or intentional (or combinations of these). Of these, causal and intentional explanations are the ones that arc most central to the social sciences, since it can be shown that all reasonable functional explanations can be expressed more clearly in causal and/or intentional terms. In sociology, and particularly in empirically oriented sociology, causal explanations dominate today, and usually take the following form: Tf the occurrence of a particular event A tends to be followed by another event B, and if there is no third event C that is likely to be the cause of both A and B, then A is said to be the cause of IF. Explanations of this sort are valuable in that they provide detailed and systematic information on when the behaviour being analysed, is likely to be observed, and on the characteristics of the actors who are likely to exhibit this sort of behaviour. Causal explanations of this sort usually remain silent, however, when it comes to questions of why event A is likely to be a cause of B, or why actors with these characteristics act the way they do. To answer these types of questions - to explain why we observe the regularities we observe - usually entails explicating the mechanism by which A generates B, and this is where intentional explanations enter the picture. An intentional explanation, unlike a causal explanation of the correlational kind, seeks to provide an answer to the question of why actors act the way they do; and to explain an action intentionally means that we explain the action with reference to the future state it was intended to bring about In this way, an intentional explanation allows us to'understand* the act, in the Weberian sense of the term. If, as argued above, all social phenomena are explicable only in terms of individuals' actions, intentional explanations are essential for understanding the social phenomena in general. Many proponents of Hrs/eben-based explanations explanations that directly refer to actors' intentions interpret this as implying that explanations consist in detailing the subjective meanings' that concretely existing actors attach to their behaviour. However, these interpretative exercises tend to produce stories about concrete cases rather than

explanations proper. Rational choice theory represents a special type of intentional explanation, which is analytic rather than concrete, and which obtains generality by the attribution of purpose to actors. The theoretical analysis consequently does not pertain to the subjective meanings and intentions of concretely existing actors but to the intentions of typical, but hypothetical, actors. To the extent that the attribution of purpose has been successful, in the sense that the intentions of the hypothetical actors approximately coincide with the actual intentions of the real actors, the analytical model will be able to shed light on the real world situation that the model is intended to explain. Analytical models such as these, that combine generality with the requirements of Vtrstcben-hzstd explanations, are in our view indispensable components of explanatory sociological theories.

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

Situotional Analysis and Rational Choice

The rationality-based approach to sociological theorizing advocated here closely resembles what Karl Popper had in mind with his notion of 'situational analysis', which he held to be the proper approach of any explanatory social science. Although Popper never fully explicated the details of this approach (e.g. Farr, 1985; Koertge, 1975), its guiding principle is perfectly clear: namely, that individuals' actions are to be explained with reference to the logic of the situation in which they occur.7 A situational analysis, according to Popper, proceeds by first making an analytical model of the social situation to be analysed. This situational model consists of elements representing the actors' decision-making environments as well as their interests (aims) and beliefs. The explanatory power of situational analysis is arrived at by working out what sorts of actions are implicit in the social situation. That is to say, concrete actions are explained by analysing how hypothetical actors would act in a situation like the one described in the situational model. In order to work out the actions implicit in the situational model, Popper meant that it is essential to assume that actors act rationally, which in this context essentially means that actors act appropriately, given their decision-making contexts, interests, and beliefs.

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH, ANDTHE SOCIOLOGICAL TRADITION

133

Popper considered the rationality postulate to be so essential for arriving at explanatory social theory that he, the great falsificationist, argued that it should be maintained even though it is usually false: I regard the principle of adequacy of action (that is, the rationality principle) as an integral part of every, or nearly every, testable social theory. Now if a theory is tested, and found faulty, then we have always to decide which of its various constituent parts we shall make accountable for its failure. My

thesis is that it is sound ntttbodologcalpolicy to decide

not to make the rationality principle, but the rest of the theory - that is, the [situational] model accountable. (Popper, 1994:177) The reason for Popper deviating from his otherwise so strongly held beliefs in falsification as the engine of scientific development is, of course, that he fully realized the model-based nature of all explanations in the social sciences. Unlike the situation in some of the physical sciences, explanatory theories in the social sciences explain typical events and these explanations are deduced from models of typical actors placed in typical situations. We fully agree with Popper that this form of situational analysis is essential for arriving at explanatory sociological theories. Its strength derives from the following facts: 1 it avoids the confusion between the abstract and the concrete by being explicitly analytical; 2 actions and intentions are at the core of the explanations; and 3 the characteristics of the social situation arc not ignored (as in the state-of-nature type of stories discussed above), but rather constitute key explanatory factors. Despite its obvious sociological relevance, Popper% form of situational analysis has not left any noticeable imprints on current sociological theory.

Some researchers and theorists in the social network tradition have developed ideas closely resembling those of Popper, however. These scholars have used networks as situational models describing action opportunities and information channels, and have assumed actors to act appropriately given this situation (see e.g. Granovetter, 1985; Burt, 1992; Mizruchi, 1992). Variations in actors' structural locations, or in their social situations, to use Popper^ terminology, are assumed to induce them to choose different courses of action; and the essence of the analysis is the explanation of individual actions with reference to the characteristics of the situations in which they occur. The network analyst who has argued most explicitly and forcefully for the usefulness of a situational approach is Mark Granovetter: The notion that rational choice is derailed by social influences has long discouraged detailed sociological analysis of economic life and led revisionist economists to reform economic theory by focusing on its naive psychology. My claim here is that however naive that psychology may be, this is not where the main difficulty lies - it is rather in the neglect of social structure. What looks to the analysts like nonrational behavior may be quite sensible when situfltional constraints, especially those of embeddcdness, are fully appreciated. (Granovetter, 1985: 506) As we interpret Granovetter^ embeddedness approach, it is essentially a Popperian approach where network models arc used for modelling the social situation, and where the rationality principle is used to work out what is implicit in the social situation. In order for situational analysis to constitute the core of explanatory sociology more generally, however, it must attain a certain level of generality and

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

Interests of actor /

Interests of actor/

/

Action of actor /

Beliefs of actor /

Opportunities of actor/

e \

\

Beiefs of actor/ Action of actor/

_

Opportunities of actor/

Figure 4. Inttraction chains making action social

134

PETER HEDSTRfiM AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

not just tell specific stories about concrete cases: in leaves an organization, a vacancy is created in this Popper's words, the situational analysis must rest on person^ old position and this vacancy constitutes a * typical situational model, capable of "explaining in a mobility or promotion opportunity for other actors. principle" (to use Hayek% term) a vast class of struc- If an individual within the organization is promoted turally similar events' (Popper, 1994:168). For such a to fill this vacancy, a new vacancy is created in this typical situational model to be useful more widely in personis old job. Someone else must be promoted to sociology it must, in addition, explicate mechanisms fill this vacancy, which in turn creates a new vacancy, that make individual action social, in the Weberian and so on. Vacancies created at higher levels of the sense of the term. Actions arc social when the choice hierarchy thus move through the organization and of one actor influences or is influenced by the provide promotion opportunities for other actors.8 choices of other actors. Given the type of action In these sorts of situations, actions are social and theory discussed above, action becomes social - highly interdependent, in that one individuals that is, interdependent - when one actoris choice action directly enables or hinders the actions of or anticipated choice of action influences the beliefs, other individuals. The operation of the vacancy interests, and/or opportunities of other actors. Ele- chain mechanism is not restricted to job mobility ments of such a model are illustrated in Figure 4. systems, but is operative in a vast class structurally One standard sociological critique of rational similar situations, such as tracking in educational choice theory is that it assumes actors to be atom- systems (Sarensen, 1983), and even in certain nonized. Given the discussion above, it should be clear human-related events, such as the movement of herwhy we do not think that this sort of critique has any mit crabs between different snail shells (see Chase, bearing on the theory of rational choice as such. The 1991). theory of rational choice is an ideal-typical action Another type of mechanism, linking not actions mechanism linking individuals' beliefs, interests, to opportunities but actions to beliefs, is the beliefand opportunities to their choice of action. Whether formation mechanism underlying several classic actors are assumed to be atomized or not is part of works of sociology during the post-war period, the more general situational model, and not the such as the self-fulfilling prophecies of Robert K. action mechanism as such. The type of interaction Merton ([1948] 1968), the network diffusion prochain illustrated in Figure 4 is an example of a situa- cesses of James Coleman et al (1996), and the tional model rendering the choices of rational actors threshold-based behaviour of Mark Granovetter interdependent and social. (1978). Merton, Coleman, and Granovetter all From the perspective of explanatory theory it is assume that individuals act adequately, given the essential that the mechanisms assumed to link one social situation they are in. The mechanism that individuals action to the beliefs, interests, and/or gives these analyses their counter-intuitive appeal, opportunities of others, are of some generality and concerns the ways in which they assume individuals' capable of explaining in principle a vast class of beliefs to be formed. More specifically, their prostructurally similar events. Space limitations only posed mechanism states that one individuals belief allow us to allude to a couple of such mechanisms in the value or necessity of performing an act is a that make action social. One important type of function of the number of other individuals who mechanism, linking one individual^ actions to the have already performed the act. In a situation charopportunities of other actors, is the vacancy chain acterized by a great deal of uncertainty, it seems mechanism of Harrison White (1970). This mechan- reasonable to assume that the number of individuals ism is operative in situations where positions and who perform a certain act signals to others the likely individual incumbents of positions are clearly sep- value or necessity of the act, and this signal will arate entities, and where vacant positions represent influence other individuals' choices of action. Meropportunities for other actors. The way in which this tonis bank customers based their (initially faulty) mechanism operates is best illustrated with an exam- judgements about the solvency of the bank on the ple. Organizations can be viewed as systems of job number of other customers withdrawing their savpositions linked to one another -through typical ings from the bank; Coleman's physicians based recruitment of promotion paths. If an individual their evaluations of the possible effect of a new

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH, ANDTHE SOCIOLOGICAL TRADITION

135

drug on the actions of their colleagues; and Granovetter's restaurant visitors based their decisions on where to cat on the number of diners already in the restaurant. It is this belief-formation mechanism that is at the heart of the self-fulfilling prophecies of Merton, the network effects of Coleman, and the bandwagon effects of Granovetter, and it is an example of another type of semi-general mechanism that makes action social. As we have argued elsewhere (Hedstrom and Swedbcrg, forthcoming), we believe that the generality of sociological theory is to be found at the level of mechanisms, and that the future of explanatory sociological theory hinges on our ability to specify and to systematize these sorts of mechanisms.

Rational Choice and Empirical Research

The limitations of causal modelling 9

In our opinion, the main reason for advocating explanations that refer directly to meaningful events - that is, to the activity that generated the data we observe - is that these sorts of explanations provide (or encourage) deeper and more finegrained explanations. The search for generative mechanisms diminishes the size of the black box and helps us distinguish between true causality and coincidental association. The distinction between black-box or variablebased explanations and explanations that refer to explicit and generative mechanisms can be illustrated in more general terms with the following example that is adopted from the work of Mario Bunge (1967). Assume that we have observed a systematic relationship between two types of events or variables, I and O. The way in which the two sets of events or variables are linked to one another is expressed by the mechanism, At:

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

The widespread use and knowledge of survey anal- What characterizes a black-box explanation is that ysis and the statistical techniques needed for the link between input and output, or between expiaanalysing survey data have clearly improved sociolo- tions and explanandum, is assumed to be devoid of gists' ability to describe societal conditions and to structure or, at least, whatever structure there may test sociological theories. But the increasing use of be, is considered to be of no inherent interest (perthese techniques has also fostered the development haps because it cannot be observed). In a black-box of a variable-centred type of theorizing that only explanation, the 'mechanism' linking input and outpays scant attention to explanatory mechanisms put is a purely syntactical link between a column of (see e.g. Esser, contribution to this issue). Coleman values for the input, I, and a column of values for the (1986) has aptly described this type of sociology as a output, O. form of 'individualistic behaviorism! The guiding One important difference between black-box principle behind this type of theorizing - usually explanations and the type of explanation advocated referred to as 'causal-modelling" - is the notion here concerns the information content of the prothat individual behaviour can and should be posed mechanism. Since the alleged 'mechanism' in explained by various individual and environmental , a black-box explanation (e.g. a regression coefficient) 'determinants', and the purpose of the analysis is to is derived exclusively from I and O, it contains no estimate the causal influence of the various variables information that is not already contained in the representing these determinants.10 According to events or variables themselves. The approach advoColeman, this emphasis on 'causal' explanations of cated here does not rest with describing the form of behaviour represented a considerable change from the relationship between the entities of interest but the type of explanatory account used in the earlier addresses a further and scientifically more challenging tradition of community studies: "One way of problem: why is there a relationship to start with?12 describing this change is to say that statistical assoOne line of sociological research that illustrates ciation between variables has largely replaced the shortcomings of black-box explanations is meaningful connection between events as the basic some of the current research on class and its tool of description and analysis" (Coleman, 1986: individual correlates. In empirically oriented 11 1327-8). sociology, individuals' class-belonging has become

136

PETER HEDSTR6M AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

a popular explanation for various individual-level phenomena such as income (e.g. Kalleberg and Berg, 1987) and health (e.g. Townsend and Davidson, 1990). Despite the common sociological rhetoric of describing class as a 'determinant' of various individual traits and behaviours, class in and of itself obviously cannot influence an individual's income or health. 'Class' is not causal agent, rather it is a constructed aggregation of occupational titles. A statistical association between 'class' and income or 'class' and health tells us that individuals from certain 'classes' have lower incomes or worse health than others, but it does not say why this is the case. To answer such questions it is necessary to introduce and explicate the generative mechanisms that might have produced the observed differences in average income or health between the occupational groups that the researchers have assigned to different 'classes'. Statistical 'effects' of a class-variable in contexts like these are essentially an indicator of our inability to properly specify the underlying explanatory mechanisms. One could even say that the worse we do in specifying and incorporating the actual generative mechanisms into the statistical model, the more 'effect' the class-variable will appear to have. Correlations and other empirical findings always call for theoretical explanations. Unless the mechanisms that may have produced the observed correlations are clearly stated, our understanding is incomplete and the explanation wanting.13 Considerable skill and intellectual energy are devoted to the task of describing how variables like 'class' and 'health^ or 'industrialism'and 'extent of meritocracy' are related to one another, while the mechanisms that may have generated the relationships are often left implicit. What is usually needed for understanding why we observe the relationships we do observe, is an analytical model that conjectures certain mechanisms that show how the values of an 'independent variable' are likely to influence the opportunities, beliefs, and/or interests of individual actors; and how their actions and interactions, in their turn, generate the values of the 'dependent variable'. And it is as an integral part of these sorts of models that rational choice theory constitutes an indispensable tool for empirical sciences such as sociology.

The Limited Use of General Purpose Surveys for the Development of Sociological Theory We do not wish to suggest that quantitative analysis of large-scale survey data is of minor importance for the sociological enterprise; quite the contrary. This sort of quantitative research is obviously essential, for descriptive purposes, for testing predictions derived from sociological theories, and for suggesting clues as to what to look for. We do, however, believe that many sociologists have had too much faith in statistical analysis as a tool for generating theories, and in the possibilities of using general purpose surveys for explaining why something happens. If quantitative research is to advance beyond the description of the 7O-type of relationships referred to above, and become directly relevant for identifying the mechanisms that link I and 0 - that is, become directly relevant for the development of explanatory sociological theory general purpose survey data is not enough. To the extent that individual action is social, in the sense discussed above, the data must contain sufficient texture to allow the assessment of the operation of the mechanisms believed to link one individual^ action to that of others - and if the data were not originally gathered with these mechanisms in mind, the power of the tests allowed for are likely to be limited. The dangers inherent in using traditional survey data when the process being analysed is social, can be illustrated with Granovetter's (1978) notion of threshold-based behaviour. As mentioned above, Granovetter's core idea is that an individual's decision to perform a certain act, e.g. to participate in a collective movement, often depends in part on how many other actors have already decided to participate. Granovetter further assumed that actors differ in terms of the number of other actors who must already have performed the act before they decide to do the same, and he introduced the concept of 'threshold' to describe this individual heterogeneity. In the context of collective movements, an actor's threshold denotes the proportion of the group which must have joined the movement before the actor in question decides to do the same. Some individuals have a threshold of 0 per cent: they are the initiators or entrepreneurs who are willing to participate in a collective action even if no one else is willing to do so. Others have a threshold of 100 per

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH, ANDTHE SOCIOLOGICAL TRADITION

137

cent - they are the true 'free-riders' who refuse to participate no matter how many others have decided to join - but most individuals have thresholds between these two extremes. An important qualitative result of Granovetter's analysis was that even slight differences in thresholds can produce vastly different collective outcomes. Assume for example a group of 100 people in which one individual has a threshold of 0, one has a threshold of 1, one has a threshold of 2, and so on up to the last individual who has a threshold of 99. Initially only the person with a threshold of 0, will participate. His or her participation will activate the person with a threshold of 1 and this person's participation, in turn, will activate the person with a threshold of 2. This process will continue until all 100 people participate. Now imagine another group that is identical with the first group except for the fact there is no person with a threshold of 1 but two persons with a threshold of 2. The groups are virtually identical and their interests in the goods or services the collective action was intended to bring about is more or less the same, but the collective outcomes they generate are dramatically different. The person with a threshold of 0, of course, will participate in this group as well. But since there is no one with a threshold of 1, the process ends at this point; only one person in the second group will participate in the 'collective' movement. If we now select a random sample of individuals from the joint population of these two groups, what is likely to happen is that the possibility of recovering the social process that generated the collective outcome is likely to be destroyed, since many individuals who were crucial in triggering sample members'actions have been excluded from the sample. Furthermore, if a traditional regression-like analysis was performed on this sample data, the results are likely to be rather misleading. Assume that the decision whether or not to participate was coded as a 01 dummy variable, that various variables describing the characteristics of the individuals were included as independent variables, and that the parameters of a logistic regression equation were estimated. The results of this analysis would then indicate that variables correlated with group membership were important for the decision to participate. If the first group was made up of men and the second group of women, or if the first group

was composed of working-class persons and the second group of middle-class persons, the results of the analysis would suggest that gender and/or class were important in the decision to participate. The results would invite speculations about gender-based or class-based differences in the propensities to join social movements. But as we know - because we designed the thought experiment the two groups are virtually identical and their preferences for the collective good, save one person, are the same. The "effect' of the class or gender variable is an artefact, due to the use of a sample that was selected without any thought for the recursive nature of the process being examined. This is, of course, an extreme example, but it illustrates the importance of using theory-driven sampling designs and the dangers inherent in testing sociological theories on the basis of data that has been collected for entirely different purposes. General purpose surveys are in many cases more suited for description and overall tests of theoretical predictions than for detailed tests of mechanismbased theories, particularly theories where social action is deemed important.

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

Rational Choice Theory and the Sociological Tradition

As mentioned in the introduction of this article, rational choice sociology is not as youthful as is commonly thought, but in reality has deep roots in the sociological tradition. Among the sociological classics, there is particularly the work of Max Weber, which to a considerable extent falls within the rational choice paradigm (for a different view, see eg. Ulteeis contribution to this issue). And of the post-Weberian sociologists, there is first and foremost Robert K. Merton, whose work, in many respects, parallels that of Weber. What makes it important to consider Weber and Merton in this context is that their work can contribute to the development of rational choice sociology. In the next few pages we will highlight aspects of Weberis and Mertonls work that are of particular importance in this context. In doing this, we also, indirectly, show that rational choice is indeed an organic part of sociology.

138

PETER HEDSTR6M AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

Max Weber

The three key elements in rational choice theorizing that we earlier argued were essential to sociology methodological individualism, analytical primacy, and intentionality (Vinteben) can all be found Max Weberis sociology. That only the individual can be an actor in sociological analysis is something that Weber insisted on very strongly. Weber was extremely hostile to the tendency in Germany in his day to use holistic entities as actors; at the most, he said, people can orient their actions to the idea of this type of entity. Just like economic theory, he concluded, 'sociology must adopt strictly individualisticmethods'.14 The idea of analytical primacy is central to Weber's work. It is, for example, present in his discussion of causality - such as the idea that causal chains are in principle infinite and that the analyst therefore has to step in and decide where to cut them off and that this decides which factors are singled out in the explanation. There is also Weber's well-known argument that the kind of concepts that sociologists should use must not only be abstractions (all concepts are abstractions) but in addition must entail an 'analytical accentuation of certain elements of reality' (Weber [1904], 1949: 90). The individual actor in Weber's sociology is conceptualized as one of these 'ideal types' and must consequently not be equated with a concretely existing individual, as seen from a psychological perspective. The individual actor in a sociological analysis is exclusively defined as the agent of 'social action' which is defined, in its turn, through the actoris orientation to the behaviour of other actors.15

theories' and not ^ways-true theories' (on this point, see the excellent discussion in Hernes 1994: 426-7). As to the concept of Ursttben, it is well known that Weber uses it mainly for explanatory purposes: the in individual actorls intention is related to his or her action; and the latter is explained by the former if there exists a meaningful and adequate connection between the two. What, however, constitutes a common misperception of Weber's ideas on intentional explanations (as we noted earlier), is the notion that the analyst must start by establishing how concrete individuals perceive reality, say via interviews. On the contrary, the analyst (Weber says) should begin the analysis by conducting an ideal type; and this analytical type is then to be used in a model which will be helpful or not in explaining a specific phenomenon, depending on its usefulness in orienting the research towards the empirical reality. In our opinion, what has just been said about Weber, clearly suggests that important parts of his programme in sociology do indeed fall within the paradigm of rational choice sociology - a position that we share with some other sociologists.17 What Weber's perspective can add to contemporary rational choice sociology is a different issue and could easily swell into a book-length study. Here, however, we shall only point to two aspects of Weber's work that are relevant in this context: namely, his concept of rationality, and his idea that as the world becomes more rational, the scope for rational choice analysis will also grow. As to thefirstpoint, we agree with Boudon (1987), that it is Weber's introduction of an expanded concept of rationality - more precisely, the distinction between 'instrumental rationality* ^jvtckmtionaiitSt) and 'value-rationality" {Wirtratwnalitaf) that is of particular interest here. Arguing for the use of 'context-bound rationality" in sociology, Boudon writes: It is alao important to see one main difference between the economic and the sociological individualistic traditions [read: rational choice traditions]. Although these two traditions hold as a postulate that individualistic actions must be considered rational% the sociological individualistic tradition gives a much broader meaning to this notion. This point is well known, and every sociology student knows, for instance, that Weber

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

When analysing social action, Weber argued, the analyst should initially assume that the action is rational, and then confront empirical reality with his or her model. If there is no meaningful fit between the two, the deviation from rationality has to be explained.16 On the other hand, if the rational model does fit the designated part of empirical reality like, say, Gresham's Lawfitsa certain empirical pattern this does not mean that it will alsofitother situations. Like Coleman (1964), Weber claimed that a model can only fit certain types of reality, not all types; social science theories are 'sometimes-true

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH ANDTHE SOCIOLOGICAL TRADITION

139

to Morton's work as to that of Weber. There are differences in emphasis, however, and while Weber produced a systematic treatise in sociology, Merton's There are two aspects of Weber's distinction between instrumental rationality and value-rational- work has evolved more through serendipity. While it ity that deserve to be highlighted. First, by joining is dear, for example, that Merton is a methodologitogether values and rationality in one single con- cal individualist, there is no formal statement to this cept - Vftrtrationalitat - Weber clearly broke with effect in his work. None the less, Mcrton"s actor is an the tendency to view 'values' and 'rationality* as individual who sets about things in a perfectly purincompatible with one another or as each other's posive and resolute manner (eg. Coser, 1975: 239). opposites. In brief, instead of seeing values as inher- From early on, Merton stressed the importance of ently irrational, Weber suggests that a value can be the individual actor making a 'choice between pursued just as rationally as any material interest; various alternatives' (Merton 1936: 895). And as values appear in the social world primarily as Arthur Stinchcombe has shown in his article on 'material interests'and 'ideal interests' in Weber's ter- Merton's concept of social structure, this emphasis minology. Second, a key difference between value on choice has remained constant in Merton's work rationality and instrumental rationality has to do (Stinchcombe, 1975). Indeed, in Merton's recent with the different role that unanticipated conse- work on the concept of 'opportunity structure', the quence play in the two. When an actor acts in an notion of 'socially structured choices' plays a key role instrumentally rational fashion, an effort is always (e.g. Merton, 1995: 29, 33). The primacy of the analytical is also an integral part made to take into account all the consequences of an action, as opposed to in value-rational action. In of Merton's work. No other sociologist has been able the latter type of action, the actor is typically satis- to conceptualize his own and others' ideas in such elefied once he or she has chosen whatever action is gant models or theorems to the same extent: the Selfmost likely to realize the ideal interest in question. fulfilling Prophecy, the Matthew Effect, theThomas Weber does not extend his analysis of unanticipated Theorem, and so on. As in Weber, one can find in consequences any further than this - something Merton the argument that a parsimonious sociowhich, however, Robert Merton has done, as will logical analysis docs not need to take psychological be discussed below. aspects into account, and that one should start with Another major theme in Weber's sociology is that the assumption of rationality and then trace deviaof rationalization. To the extent that rationalization tions from it (e.g. Merton [1936] 1976:147). Two of Merton's most important contributions to is treated as some kind of philosophy of history (as sociology, his theory of social structure and his elaWeber himself sometimes treated it), it is of little interest to sociology. The idea that the scope for boration on the theme of unanticipated conserational action may increase under certain empirical quences, are also of interest to rational choice socioconditions - and that it has increased considerably logy. While many theorists tend to view social in certain spheres of Western society - is, on the structure in terms of positions that exist independent other hand, a suggestive idea. Weber argued, for of the individual, the thrust of Merton's analysis is example, that 'the historical peculiarity of the capita- different. For him, the building blocks of social listic epoch' has to do with the fact that 'the structure are rather the individual's choice and the approximation of reality to the theoretical proposi- means and ends that are used to realize specific interests. tions of economics has been a constantly incnasmg one" Arthur Stinchcombe (1975), who has discussed (Weber [1908] 1975: 33) - and the same argument Merton's theory of social structure in a well-known article, summarizes Merton's theory of social struccan be made for rational choice sociology. ture in the following terms: 'individual choice behavior' aggregates into 'rates of institutionally consequential behavior*, and these affect the 'instituRobert K. Merton tional patterns shaping alternatives', which in their Methodological individualism, analytical primacy, turn affect the initial 'individual choice behavior" and intentionality (Wrrttben) are equally important (see Figure 5).

introduced the notion of Mrtmtioiiafflt beside what is called Zwtckrntioiulitai. (Boudon 1987: 63-4)

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

140

PETER HEDSTROM AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

Institutional patterns shaping alternatives

Individual choice behaviour motives, information, sanctions, bearing on the alternatives presented

Rates of institutionally consequential behaviour

Structural induction of motives, control of information, and sanctions Development of social character

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

F i g u r e d RobertK. MertontTbtary of SodaJ

Structim,asswmrnai^lyArtbwSthicbaml>e.So\jiVx:Stiiubcombe(1975),11

Although Stinchcombc uses a slightly different terminology from the one we used above, his summary statement brings out the obvious parallels that exist between Merton's conceptual scheme and the type of rational-choice-based situational analysis advocated above. The focus of the analysis in both cases is explaining why individuals placed in different regions of the social structure or in the terminology used above, in different social situations tend to choose different courses of actions. Furthermore, these actions are explained in terms of different action alternatives (opportunities), different motives (interests), and differential access to relevant information. Finally, both in Mcrtorfs social structural paradigm and in situational analysis, the variation in these proximate causes of action is explained with reference to the characteristics of the actors' social situations.18

One aspect of unanticipated consequences, Merton says, which is amenable to analysis has to do with what caused them, and he here suggests a typology of five different sources: 'ignorance','error' 'imperious immediacy of interests'.'basic values', and 'self-defeating predictions' (cf. Merton [1936] 1976: 154). As to the first of these, 'ignorance' Merton notes that the more immediate an action is, the more likely it is that the actor will not have had time to gather enough information; he also points out that in certain situations it might be rational not to gather enough information, given the scarcity of energy and time. 'Errors' may also cause unintended consequences; and the example Merton uses is that of a perfectly rational habit which, however, leads the actor wrong when he or she is encountering new circumstances. The term 'imperious immediacy of interests' indicates a situation where the actor is so eager to realize his or her interests, Merton's article 'The Unanticipated Consethat he or she so-to-spcak overshoots; the interest quences of Purposive Social Action' (1936) is also is so strong that the action does not accomplish of relevance in this context Here Merton notes that what it is intended to do - and hence creates uninmany thinkers before him - including Weber tended consequences. "Basic values' covers the same have noticed the phenomenon of unanticipated situation as Weber^ notion of value-rationality, consequences, but that little systematic work has namely that the believer tends to disregard the con19 been done on this topic. Drawing especially on sequences of what he or she considers to be the the work of Frank Knight in Risk, Uncertainty and rational choice in a situation.'Self-defeating predicProfit (1921), Merton says that purposive action tion' source number five for unintended always entails "a choice between various alternatives" consequences - represents the opposite of a selfbut he emphasizes that this choice has nothing to do fulfilling prophecy: something that has been prewith psychology (Merton 1936: 895).

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH, ANDTHE SOCIOLOGICAL TRADITION

141

dieted to happen, will not happen, precisely because the actors have become aware that it may happen and therefore decide to stop it. What Melon's analysis of social structure and unintended consequences can contribute to a rational choice sociology becomes clear if we compare bis ideas with those of Popper on situational analysis. Popper, to recall, argues that if we know what situation a typical actor is in, and if we make the assumption that the actor is rational, then we will be able to predict what he or she will do. The example that Popper used in his famous talk in 1963 on the principle of rationality is that of a pedestrian who is in a hurry to cross a road in ordei to catch a train: given the intention and the situation, we can predict how this will be done. What Popper has practically eliminated from his analysis, however, is the element of social structure or the interaction between different actors, and this is where Merton's analysis of social structure, as well as of unintended consequences, comes into the picture. Single actions may under certain circumstances, as we know, become 'institutionally consequential' (Stinchcombe), and these institutional effects can be intended as well as unintended. What appears sociologically most interesting is obviously situations that are such that they tend to give rise to interdependent social action. It is in these types of situations - i.e. situations when one individual's action, directly or indirectly, influences other actors' opportunities, beliefs, and/or interests - that unanticipated consequences are likely to loom large. And it is the characteristics of these types of situations that Merton focused on in his theory of social structure.

Concluding Remarks

Over the last few decades, sociologists' ability to produce good and relevant descriptions of social situations has improved considerably, because of both access to better quality data and the use of more appropriate and sophisticated statistical techniques. As many previous commentators have observed, sociological theory has not progressed in a similar manner, and there also appears to be a growing dissatisfaction within the discipline about the explanatory power of sociological theory.

We believe that at the root of this problem lies an unfortunate separation between empirical and theoretical work, and in this paper we have argued that the infusion of rational choice theory within sociology can contribute to a narrowing of this gap. Rational choice theory provides an action theory that represents a useful micro-foundation for macro-theories in many branches of sociology, and rational choice theory also represents a type of theorizing that deserves to be emulated more widely in sociology. This type of theorizing is analytical; it is founded upon the principle oimttbodologicalindividualism; and it seeks to provide causal cum intentional explanations of observed phenomena. This type of analytical and deductive theorizing is important because it encourages deeper and more fine-grained explanations of observed events than the variable-centred type of theorizing that currently dominates empirically oriented research. The notion of what an explanation entails is very limited in variable sociology, and is often restricted to estimating the strength and functional form of statistical relationships between variables. However, proper explanations of observed relationships entails explicating the mechanisms through which the relationship was produced, and this usually requires direct reference to the actions and interactions of individuals. Gudmund Hemes sums up our position on the relationship that should exist between theoretical and empirical work in this manner: *an empirical regularity begs for a model to interpret it; a model begs for a regularity to interpret' (Hernes, 1994: 435). But, if quantitative research is to have more bearing on the development of sociological theory, the practice of quantitative research also needs to change. First of all, the focus of the research must become theoretically more relevant Today, most empirical sociological research is guided more by the political and social issues of the day than by the potential contribution it can offer to the development of sociological theory. That these sorts of influences can be an important obstacle to scientific development is a point emphasized already by Thomas Kuhn.20 Secondly, and partly as a result of the policy focus of much empirical sociological research, general purpose surveys have come to be a dominant source of data for empirical researchers. These types of data

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

142

PETER HEDSTRdM AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

3. Interests, beliefs, and opportunities also interact in complex and interesting ways, but these interactions do not need to concern us here, 4. See Boudon (1989) for a slighdy different view on the role of 'unreasonable' beliefs in rational choice explanations; see also BlossfeldV (1996) discussion of Elstcr in this issue. In a different article on this theme, John Gold5. Friedman takes a rather extreme position with regard thorpe (1996) discusses the relationship between to theory-building: no matter how obscure the analyses of large quantitative data-sets and rational assumptions or explanatory mechanisms are, a thechoice theory. We agree with much of what he says, ory with better predictive ability is always to be but we also feel that his argument needs to be compreferred. However, the use of rational actor models plemented by a discussion of small, but strategically in the social sciences is not only, or even primarily, chosen data-sets. In our view, the best way of develdue to its superior predictive power; equally imporoping as well as of testing new aspects of rational tant is the fact that the proposed explanatory mechanism has considerable face validity. In Sen% choice theory (as well as sociological theory more terminology, the rational choice postulate is not a generally) is to use a data-set where the theory to be false but an incomplete description of the principles tested has guided the collection of data. The reader guiding the behaviours of decision-making units. may recall such studies as those by Torsten HagerHence, even though rational choice theory is an strand on the spread of technological innovations; importrant instrument for making predictions, it is by James Coleman, Elihu Katz, and Herbert Menzcl not merely an instrument, as Friedman seems to on the introduction of a new drug; and by Mark imply; it also is a theory that offers genuine insights Granovetter on the way that information about job into the complexities of existing social systems (see opportunities travels through weak versus strong Popper, 1994). ties. What makes these studies so valuable is exactly 6. Alfred Marshall, when discussing the use of abstract that they launch a new idea while the question of reasoning in economics, advanced a similar argurepresentativeness and generalization to large social ment regarding the necessity of short chains of units, such as a national population, is less important deductive reasoning. See Marshall [1920] 1986: 644. at this stage of the research process. To our earlier 7. Popperfc most detailed discussion of sicuational anaarguments that rational choice sociology can be of lysis can be found in his famous essay on the help in narrowing the gap between theory and rationality principle, based on a talk given at the Department of Economics of Harvard University in empirical research, we should therefore add that in 1963 (Popper, 1994). See also Popper (1966). many situations small, but strategically chosen study 8. The logic of vacancy chains within organizations is populations are of crucial importance. more fully developed in Hedstrdm (1992). 9. In Hcdstrflm and Swedberg (forthcoming) we discuss in greater detail the limitations of causal modelling as an explanatory strategy. 10. The affinity between behaviourism and structural equation modelling was also noted by O. D. Duncan: In [structural equation] models that purport to 1. For previous work along these lines, see in particular explain the behavior of individual persons, the coefColeman (1986, 1990). See also Wippler and Lindenberg (1987) as well as the various contributions in ficients [of the structural equation] could well take Abell (1991) and Coleman and Fararo (1992). the form of units of response per unit of stimulus 2. Since many sociologists seem to misunderstand the strength; the structural equation is, in effect, a stimuimplications of this assumption, it should be explicitly lus-response law' (Duncan, 1975:162-3). pointed out that these individual preferences also can 11. Throughout his career, Coleman was a strong propoinclude the well-being of other actors. Thus the nent of a generative view of causality and he often rational choice framework is not restricted to the anaexpressed serious doubts about the usefulness of the lysis of purely selfish behaviour. For Webcrls similar type of causal analysis referred to above. Already in point - using the notion of 'ideal interest' - see Introduction to Mathematical Sociology he wrote: "Note, later in this paper. however, that there is nowhere the proposal simply are excellent for descriptive work, but they rarely contain sufficient texture to shed light on the mechanisms believed to link one individual^ action to that of others nor to generate insights into the micro-level processes that might have generated the data being observed.

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

Notes

RATIONAL CHOICE, EMPIRICAL RESEARCH, ANDTHE SOCIOLOGICAL TRADITION

143

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

to engage in curve-fitting, without an underlying 18. It may be added that Merton* famous analysis of anomie is cast in these terms as well, though a dismodel which expresses a social process. If the data tinction between 'means' and tnds' has now been happen tofita simple curve, this may provide an ecoadded: the actor can choose between accepting socinomical statement of the data, in terms of the one or ety's means as well as goals ('conformity"), accepting two parameters of the distribution curve. But if there the goals but not the means ('innovation"), and so on is no underlying model with a reasonable substantive (Mcrton 1938, revised version 1968). interpretation, little has been gained by such curve 19. The modern analysis of this problem dates from Carl fitting" (Coleman, 1964: 518). Monger's argument in the Mttbodtnstrtit that many It should be emphasized that the distinction between social structures' like money, market prices and "black boxes'and 'mechanisms' is to some extent timerates of interest arc 'the unintended result of innubound. In the words of Patrick Suppes (1970: 91): merable efforts of economic subjects pursuing "From the standpoint of either scientific investigation individual interests' (Menger [1883] 1985: 158; cf. or philosophical analysis it can fairly be said that one pp. 13959). Weber would soon echci a similar opiman* mechanism is another man* black box. I mean nion: 'the fundamental substantive and by this that the mechanisms postulated and used by methodological problem of economics is constituted one generation are mechanisms that are to be by the question: how are the origins and persistence explained and understood themselves in terms of of the institutions of economic life to be explained, more primitive mechanisms by the next generation.' institutions which were net purposefully created by It is important to note that simply making up an*/hoc collective means, but which nevertheless function story tailored to a specific case does not constitute an purposefully?' (Weber [1903-6] 1975: 80). According acceptable sociological explanation. Even moderto Hayek,'the aim of social studies is "to explain the ately talented journalists are able to make up these unintended or undesigned results of many men"' ad hoc stories, and, as Arthur Stinchcombc once (Hayek, 1967: 100). And, finally, Popper has written noted, * student [of sociology] who has difficulty a that 'the characteristic problems of the social sciences thinking of at least three sensible explanations for arise only out of our wish to know the unintendednmseany correlation that he is really interested in should quautt, and more especially the unwanted constqtanca probably choose another profession' (Stinchcombc which may arise if we do certain things' (Popper, 1968:13). Serious, non-commonsensical, sociological 1965:124). explanations require mechanisms of some generality. The quote comes from an unpublished letter by Weber 20. 'Such [socially important] problems can be a distraction, a lesson brilliantly illustrated by several facets of to economist Robert Liefmann, dated 9 March 1920, seventeenth-century Baconianism and by some of and cited in an article by Wolfgang Mommsen (1965: the contemporary social sciences' (Kuhn, 1970:87). 44). The full quote reads (in Mommsen* translation): If I have become a sociologist (according to my letter of accreditation), it is mainly in order to exorcise the spectre of collective conceptions which still lingers among us. In other words, sociology itself can only proceed from the actions of one or more separate Abell, P. (ed.) (1991) Rational Choice Theory. Edward Elgar Publishing, Aldcrshot. individuals and must therefore adopt strictly individualistic methods'. Cf. also Weber [1921-2] 1978: Alexander, J. C. (1988) The new theoretical movement. In 13-15. Smclser, N. (cd.) Handbook of Sociology. Sage, London, 77-102. For Weber* notion of causality, see Weber [1904] 1949, [1905] 1949; for his distinction between sociology and Baron, J. N. and Hannan, M. T. (1994) The impact of economics on contemporary sociology, Journal of psychology, sec eg. Weber [1921-2] 1978: 18-19, and for the definition of social action, see Weber [1921Economic Literature, 33,1111-46. 2] 1978:4. Blau, P. M. (1977) Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory ofSocial Structure. Free Press, New York. For Weber* idea that the analysis should start from rational action, sec e.g. Weber [1921-2] 1978: 6; [1917] Blossfeld, H. P. (1996) Macrosociology, rational choice theory and time: a theoretical perspective on the 1949: 41-2. empirical analysis of social processes, European SocioloSee Boudon (1987), Hcrncs (1994), and Hechter and gical Review, 12/2,181-206. Kiser (1995). See also in this context the use made by Coleman and Hernes of Tbt Protestant Ethic (Cole- Boudon, R. (1982) The Unintended Consequences of Social Action. St Martin's Press, New York. man, 1986,1990: 6-10; Hernes, 1989).

Downloaded from esr.oxfordjournals.org at Pontif?cia Universidade Cat?lica do Rio de Janeiro on July 1, 2011

References

144

PETER HEDSTROM AND RICHARD SWEDBERG

sociological alliance. European Sociological Review, Boudon, R. (1987) The individualistic tradition in 12/2, 109-26. sociology. In Jeffrey Alexander eta/, (eds.) The MicroMacro Link. University of California Press, Berkeley, Granovetter, M. (1978) Threshold models of collective behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 83, 45-70. 1420-43. Boudon, R. (1989) Subjective rationality and the explanation of social behavior, Rationality and Society, Granovettcr, M. (1985) Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedncss. American Journal 2,173-96. ofSociology, 91, 481-510. Boudon, R. (1995) How can sociology 'Make sense' again?, Scbwit^iriscbt Zeitungfur Scr/iologie, 21,233-41. Hannan, M. T. and Carroll, G. R. (1992) Dynamics of Bungc, M. (1967) Studies of the Foundations, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science, iii, Scientific Research, SpringerOrganisational Populations. Oxford University Press,

Verlag, Berlin.

Burt, R. S. (1992) Structural Holts: The Social Structure of

New York. Hayek, F. A. (1967) The results of human action but not of

human design. In Studies in Philosophy, Politics and

Competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mast.

Castles, F. C. (ed.) (1993) Families of Nations: Patterns of Public Policies in Western Democracies. Dartmouth,

Economics. Routlcdge & Kegan Paul, London, 96-105. Hechter, M. and Kiser, E. (1995)^4 Proposal for Conducting