Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Health Education & Behavior

Transféré par

Raheem BrooksDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Health Education & Behavior

Transféré par

Raheem BrooksDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Health Education & Behavior

http://heb.sagepub.com Coming Up in the Boogie Down: The Role of Violence in the Lives of Adolescents in the South Bronx

Nicholas Freudenberg, Lynn Roberts, Beth E. Richie, Robert T. Taylor, Kim McGillicuddy and Michael B. Greene Health Educ Behav 1999; 26; 788 DOI: 10.1177/109019819902600604 The online version of this article can be found at: http://heb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/26/6/788

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Society for Public Health Education

Additional services and information for Health Education & Behavior can be found at: Email Alerts: http://heb.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://heb.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://heb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/26/6/788

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

Coming Up in the Boogie Down: The Role of Violence in the Lives of Adolescents in the South Bronx

Nicholas Freudenberg, DrPH Lynn Roberts, PhD Beth E. Richie, PhD Robert T. Taylor, MPA Kim McGillicuddy Michael B. Greene, PhD

This article presents data gathered from young people in a poor urban community in New York City, the South Bronx. It seeks to help public health professionals better understand young peoples perceptions of violence in the context of their daily lives. Sources of data include a street survey, five focus groups, interviews with incarcerated young males, and observations of several youth programs. These data suggest that violence is pervasive in the lives of both young men and women, although gender plays an important role in shaping the experience of violence. Other factors that influence the experience of violence include patterns of substance use, availability and use of weapons, and a perception that the police do not respect young people. Despite numerous challenges, many young people do take actions to reduce violence. The article suggests actions public health professionals can take to strengthen the ability of families, schools, youth organizations, and young people themselves to reduce violence in low-income urban communities.

Violence is a pervasive presence in the lives of young people in urban communities in the United States. Despite recent declines in murder rates, homicide is a leading cause of

Nicholas Freudenberg is a professor and director of the Program in Urban Public Health, Hunter College, City University of New York. Lynn Roberts is an assistant professor, Program in Urban Public Health, Hunter College, City University of New York. Beth E. Richie is an associate professor, Department of Criminal Justice, University of Illinois, Chicago. Robert T. Taylor is a project coordinator, Program in Urban Public Health, Hunter College, City University of New York. Kim McGillicuddy is the director of Youth Force, Bronx, New York. Michael B. Greene is executive director of the Violence Institute of New Jersey, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark. Address reprint requests to Nicholas Freudenberg, DrPH, Program in Urban Public Health, Hunter College, City University of New York, 425 East 25th Street, New York, NY 10010; phone: (212) 481-4363; fax: (212) 481-5260; e-mail: nfreuden@hunter.cuny.edu. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Angela Martinez and Ana Motta-Moss for data analysis; Hunter College students Keisha Lugay, Chris DAnguilan, Nkeche Oguaghe, Claire Simon, and Eunice Paul; John Burghardt and Karen Needles of Mathematica Policy Research Incorporated for the data on incarcerated males; the young people of Youth Force for their development and administration of the street survey; and Susan Wilt and Wendy Chavkin for their helpful editorial suggestions. The research described here was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the participating or sponsoring organizations.

Health Education & Behavior, Vol. 26 (6): 788-805 (December 1999) 1999 by SOPHE

788

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

789

death and injury among young people, especially those in urban areas.1 A recent study found that one in four adolescent girls in the United States has been sexually or physically abused or forced to have sex against her will.2 National surveys show that almost one-fifth (18%) of high school students have carried a weapon to school at least one day in the last month and that 37% had engaged in a physical fight in the last year.3 Numerous studies over the past 10 years have documented high rates of exposure to violence among children and adolescents, particularly within urban neighborhoods.4-14 Many of these studies have documented adverse psychological and behavioral consequences of such exposure, including depression, hopelessness, acting-out behavior, delinquency, risky sexual behavior, and substance abuse.4,7,9,11-13 In recent years, the problem of youth violence has attracted the attention of public health researchers, elected officials, and the media. Too often, however, the public discourse on violence reflects the attitudes and beliefs of adults, especially those in more privileged positions, rather than of young people themselves. This article presents data gathered by university-based researchers from several sources in a single low-income urban community in New York City. The goal is to help public health professionals better understand young peoples perceptions of violence in the context of their daily lives in order to help young people and communities design more effective interventions to reduce violence. Since this article presents findings from one community, its relevance to other urban areas will need to be assessed. Another aim is to describe a methodology for relatively rapid and low-cost assessment of a social problem in a specific community. The process described seeks to engage researchers, service providers, and young people in defining the problem, collecting data, and interpreting the findings; create forums for those often excluded from the policy arena to voice their opinions; and initiate an iterative process by which a community and researchers can work together to create, apply, and test knowledge about complex urban phenomena such as youth violence. The team of investigators sought to answer four questions: 1. How do young people in the South Bronx experience violence in their lives, whether in the home, school, or community? 2. How do these experiences influence their behavior? 3. How does the experience of violence differ by age, gender, and housing environment (e.g., public housing vs. other types of housing)? 4. How is the experience of violence related to other forces in these young peoples lives such as family life, sexuality, substance use, employment, school, mass media, and interactions with police? The overall purpose of these studies was to assist a partnership between a universitybased research action center and a coalition of community-based youth organizations in designing initiatives at both the organizational level and the community level to reduce violence in the South Bronx.

THE COMMUNITY The South Bronx includes the poorest congressional district in the United States. It comprises several neighborhoods and has a total population of 470,703. Table 1 provides

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

790

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

Table 1.

A Demographic and Health Profile of the South Bronx South Bronxa 470,703 8.5% 46% 60% 15% 48.2%-56.3%c 9.5%-14.9%c 9.8-11.5c 15.4-22.4c 58.2-76.3c New York City 7,319,759 6.3% 36% 31% 40% 22.2% 8.8% 8.9 10.5 26.7

Characteristic Total population Proportion of population aged 15-19 Race/ethnicity of population aged 15-19 Black Hispanicb White Proportion of households with annual income less than $15,000 Health indicators Infant mortality rate (1995) % Births with low birth weight (1995) % Births to teenagers (1995) Homicides per 100,000 (1991)

a. The South Bronx is defined as Community Planning Boards 1-6, which represent approximately the same area as United Hospital Fund neighborhoods 5, 6, and 7, Crotona-Tremont, Highbridge Morrisania, and Hunts Point Mott Haven. b. Hispanics can be either White or Black, so totals can be more than 100%. c. Range represents values for the three United Hospital Fund neighborhoods that constitute the South Bronx. SOURCE: Refs. 15-17.

demographic, socioeconomic, and health data on its population. Compared to New York City as a whole, the South Bronx has more than twice the rate of poverty; a greater proportion of adolescents; and higher rates of health problems such as infant mortality, low birth 15-17 weight, births to teenagers, and homicides. Media images of a neighborhood in flames and of presidential visits to survey the horrors of deteriorated housing and long-term unemployment have made the South Bronx a national symbol of urban decay. It is also true that the South Bronx has considerable assets, among which are a history of social change movements, a rich network of community organizations and health and social service agencies, and families dedicated to protecting and educating their children.18-22 In the last decade, substantial housing and economic redevelopment, as well as dramatic reductions in crime and homicide, have made some officials and residents more 20 optimistic about the future of the South Bronx.

METHODOLOGY To maximize the use of the limited funds available for this project and to preserve resources for intervention rather than needs assessment or research, researchers and community partners used data obtained from several sources including needs assessment studies, small-scale research projects on various populations of youth affected by violence, a survey of youth conducted by a participating community organization, and data from other studies in the South Bronx conducted by university-based researchers. Research studies conducted by university-based investigators were approved by the universitys institutional review board. In all studies, investigators and interviewers were

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

791

prepared to refer young people with violence-associated problems to appropriate services in the community. Since the purpose of the study was to inform the development of violence prevention programs by agencies in the South Bronx, data were selected to provide information about the perceptions and experiences of specific groups of youth. In addition, different quantitative and qualitative methodologies were used to balance the limitations of each and to enable integration of many sources of information. Other investigators have 23-26 described the benefits of using multiple data sources and methodologies. Street Survey of Young People A youth organization dedicated to empowering low-income young people to participate in social action designed and carried out a survey, which they called Coming Up in the Boogie Down (Boogie Down is slang for the South Bronx), of young people living in one neighborhood in the South Bronx. The group trained its members to recruit and 27 interview young people in various street settings. The goal was to recruit young people through street outreach methods, a common form of recruitment for youth agencies that are not school based. A convenience sample of 169 young people between 12 and 21 years completed the 30-minute semistructured interview, which covered topics such as education, housing, perceptions of community life, and experiences with violence. To achieve a balance of young people living in public and other types of housing, interviewers recruited extensively within and near public housing projects. Standard statistical tests were used to assess the significance of associations between variables of interest. Table 2 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the 169 survey respondents. Public Housing Project Focus Group To enrich the findings of the street survey, a focus group composed of young people living in a public housing project was conducted. Nine young people (five women and four men) aged 12 to 16, members of a youth program located in the housing project, provided their views of project life and their perceptions of violence. A summary describing recurrent themes was prepared. Young Womens Focus Groups To understand the perspective of young women concerning violence, three focus groups for adolescent women aged 13 to 19 were held. A total of 27 young women were recruited from three agencies. Each 2-hour session followed a structured series of questions designed to elicit perceptions of violence and its impact on these womens lives. Based on a review of these written summaries, an article identifying several recurring themes was prepared. Observations of Youth Programs Staff and students from the university served as volunteers or coordinators for three community-based youth interventions in the South Bronx during the period of study. They maintained logs and field notes of their interactions with youth and program staff. The purpose of this component was to better understand the experiences of young people

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

792

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

Table 2.

Characteristics of Young People Interviewed in the Street Survey (N = 169) n 95 73 77 68 18 13 2 4 59 89 20 76 91 78 150 % 56 43 46 41 11 8 1 3 35 53 12 46 54 47 92

Characteristic Gender Male Female Ethnicity/racea Latino-Caribbean African American Other Latino African Caribbean White Other Household composition Two parents One parent Other Housing Public housing Other housing Employment Have a job Education Currently in schoolb NOTE: Age range = 12-21, median = 15.7. a. Response categories not mutually exclusive. b. Last grade completed = 8.9, SD = 1.8.

and staff in different types of organizations and to develop recommendations for implementation by existing agencies. Field notes and logs were reviewed to identify organizational characteristics that facilitated or blocked involvement in formal and informal violence prevention activities. Interviews With Incarcerated Adolescent Males A significant proportion of young men in inner cities are involved in the criminal justice system, and this population plays an important role in urban violence. We reviewed findings from a group of jailed adolescent males whom we had interviewed for another study to better understand their experiences related to violence. In that study, a randomized trial was being used to evaluate the impact of an intervention to reduce drug use and rearrest among adolescent males 16 to 18 years old incarcerated in New York City jails. Intake interviews were completed with 194 young men who volunteered to participate in this study in 1997 and 1998 and were subsequently released 28,29 Prior to arrest, all participants lived in the South Bronx or a geointo the community. graphically adjoining community with similar social characteristics. The interviews were conducted in the jail by caseworkers who referred these young men to community organizations to receive services for the problems they identified after their release from jail. Table 3 presents data on the demographic characteristics of this population.

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

793

Table 3.

Characteristics of Young Men Interviewed in Jail (N = 194) n 43 120 12 2 17 14 56 151 % 22 62 6 1 9 7 29 78

Characteristic Ethnicity/race Latino Caribbean African American African Caribbean White Other Homeless in past year Employment Worked within 6 months prior to arrest Education Enrolled in schooling in year prior to arrest

NOTE: Age range = 16-18, median = 17. Mean number of prior arrests = 2.9.

Discussion With Community Partners Findings from these five studies were presented to the community advisory board of the university/community partnership, which includes staff of community organizations and young people living in the South Bronx. This group offered a wide range of comments, suggestions, and interpretations of the findings. A written summary of these comments was prepared to inform this article. Limitations Each of the studies described here has methodological limitations. None is based on a representative sample of young people in the community, and all except the street survey and incarcerated sample selected young people already connected to some youth-serving organization. Information on youth who chose not to participate is not available, nor did participants reflect the full range of young people living in the South Bronx (e.g., recent immigrants or homeless youth). The different methodologies for sample recruitment, interview procedures, and data analysis precluded meta-analyses of data across studies or quantitative comparisons of findings from the different substudies. Strengths Despite these limitations, the combination of data sources and methods offers multiple perspectives on the role of violence in the lives of young people. Each sample was drawn from the larger universe of young people who are reached by youth-serving agencies in the community, and the different recruitment methods provided us with participant diversity: male/female, Black/Latino, older/younger, institutionalized/living at home, public/ private housing residents, and those in/out of school. Other researchers have had difficulty reaching these sectors of low-income urban youth. While many have used national probability samples or large school-based populations, allowing for broader generalizations, this study provides multiple perspectives on the nature and process of exposure, victimization, and perpetration of violence by youth in a low-income urban community.

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

794

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

FINDINGS The findings are presented by theme, and the source for each is specified to maximize the use of the diverse data sources. 1. Violence Is Pervasive in the Lives of Young People Young people in the South Bronx are witnesses, victims, and perpetrators of violence in many dimensions of their lives. According to the street survey, 89% of respondents personally knew someone who had been beaten up. 68% knew someone who had been stabbed. 65% knew someone who had been shot. 60% had witnessed someone being beaten up, 25% someone being stabbed, and 23% being shot. 23% had been beaten up, 10% stabbed, and 8% shot. 20% reported that they had experienced unwanted sexual touching or rape. These rates of exposure to violence are higher than comparable figures for national samples but within the range of those reported in similar urban neighborhoods.3,4,8,9,11,12 The young people also described high levels of using violence or intimidation in the previous 6 months: 61% had pushed, grabbed, or shoved someone. 59% had hit or punched someone. 17% had threatened someone with a weapon. 15% had hurt someone badly enough to need medical attention.

These and other experiences may have contributed to a perception of danger. Almost one-half (46%) reported that they did not feel safe in the building in which they lived, and 35% said they were sometimes afraid of living in the South Bronx. The young men interviewed in jail also described considerable levels of violence. More than one-quarter (26%) reported that they had been physically or sexually abused. Eleven percent reported that they had attempted suicide at some point in their lives. They had been arrested an average of 2.9 times prior to the current arrest, and 46% had previously been sentenced to jail or prison. Many respondents described high levels of violence within correctional facilities. Forty percent were currently in jail on a violencerelated charge; another 43% were incarcerated for drug charges. In the young womens and the public housing focus groups, almost every young person could recount some relatively recent personal experience with violence. Verbal threats and taunting constituted a continual refrain in their lives. Young women described the additional burden of sexual comments by males in school and on the street. Focus group participants articulated an implicit ecology of violence in which setting, time of day, type of violence, and perpetrator interacted to create specific patterns of risk that shaped young peoples behavior. For example, one young man in the public housing group noted that a local fast food establishment was not a safe place to hang out but that the housing project grounds were safe, at least in daylight hours.

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

795

2. Gender Plays a Powerful Role in Shaping the Experience of Violence Both young men and young women in the South Bronx experience high levels of violence, but gender plays a powerful role in shaping the impact of this violence. According to the street survey of youth: Males were more likely to report victimization in such categories as ever being beaten up (28% male vs. 14% female, p < .05), stabbed (14% vs. 3%, p < .05), or shot (12% vs. 1%, p < .05). Gender differences were not significantly different in other categories, including sexual victimization, or witnessing or experiencing other types of violence. Young men and women did not report significantly different rates of violent behavior in the past 6 months, including hitting, punching, or threatening someone with a weapon, carrying a gun, or getting in trouble in school because of violence. Gender differences in victimization are consistent with other studies of comparable 4,8-10,14 and others have reported high rates of violence among young women.30 populations, Some researchers, however, suggest that while arrests of women may have increased, levels of violence are stable.31,32 Young women in the focus groups provided a possible explanation of this unexpected similarity in rates of violent behavior. They speculated that women had become more aggressive in recent years. We are stronger and dont take shit anymore, said one young woman, but as a result, we get in more trouble now. Several participants also stressed the importance of not acting like a victim. Young women described situations in which they decided to initiate aggressive action to avoid appearing weak or afraid. Male/female relationships contributed to vulnerability to violence in a number of ways. At youth programs, observers noted frequent male harassment of females, ranging from teasing to more explicit, unwanted sexual advances. One focus group participant described an incident in which a group of girls cut school to attend a hooky party with a number of boys. One of the young women was sexually assaulted by several boys, and other girls reported knowledge of similar events. When asked to comment on these assaults, young women expressed the hope that they would not be so unlucky as to find themselves so victimized. Intimate relationships could also be problematic. Young women described relationships that began and ended rapidly. Young women wanted traditional relationships in which partners would take care of each other, an idealized goal that was rarely achieved. Young women reported that most people they knew were in a relationship all the time, moving from one partner to another when a romance ended. Young women noted that heterosexual peer relationships are problematic because boys do not always know their roles. Young women described their male peers as immature, irresponsible, insecure, and not knowing what girls need. Some of the young women ascribed these problems to male lack of knowledge, experience, and role models. These dynamics made violence more likely on several levels. Several young women felt that they were at constant risk of losing the relationship, and hence worked to keep it, sometimes putting up with violent or abusive behavior. Young men were described as holding most of the power in the relationship, particularly concerning its nature and length,

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

796

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

leading to female feelings of vulnerability and powerlessness. The competition for males and the ways some young men manipulated this became a major source of conflict between the young women, sometimes leading to physical fights. Some young women reported that they decided to avoid the problems of younger men by choosing older male partners. This decision may further exacerbate the power differential between the two partners. Some recent research suggests that young women in relationships with older 33 men are more vulnerable to violence and other health problems. Finally, the participants explained that they believed that the cumulative effects of betrayal and mistreatment contributed to feelings of low expectations for themselves, low self-esteem, and lack of sympathy for others in the same situation, feelings that they believed increased their vulnerability to violence. The focus groups with young women provided an opportunity to explore their definitions of violence and the impact of different categories of violence. They described three distinct forms of violence. The first, labeled abuse, was characterized by hitting, punching, beating, extreme verbal intimidation, or sexual violence by a family member or someone in an intimate relationship (e.g., a boyfriend). Participants noted that in abusive relationships, one partner had more power than the other. Young women generally said that they were unable to fight back in an abusive relationship because of the power difference and found a passive response more self-protective. Young women also identified abuse as the most degrading and damaging form of violence. They distinguished between abuse, which occurred in a long-term intimate relationship with a more powerful person, and assault, which was a single or rare event carried out by a less well known person. A second category of violence was fighting between peers or siblings. The young women described this type of violence as occurring between relatively equal individuals. Fights started with a disagreement or argument. Frequently, the immediate cause of the fight was the desire of one participant to show she could not be victimized, a motive also reported by young men in the public housing focus group and in the youth programs. Less frequently, females reported that they fought with each other about a male. The third category young women described was play fighting, verbal assaults, and threats. While this often started innocently, the pushing or name calling sometimes led to physical fights. Verbal threats also forced some young people to alter their patterns of behavior. One young woman said she stopped attending an after-school program because she had beef with several other girls there. In the focus groups and the observations of youth programs, play fighting and teasing were described both as occurring between equals and as a form of bullying of those perceived to be weaker. It is worth noting that young women rarely described the random violence that often dominates media portrayals of urban life. Mostly, the young women knew the people with whom they had violent or abusive interactions. 3. The Roles of Victim and Perpetrator Are Not Always Clearly Distinguishable In both the popular media and the criminology literature, victim and perpetrator are often clearly distinguished roles. These differences were not so apparent to the young people in the South Bronx. Focus groups members reported that the initiator of teasing or taunting sometimes became the victim of physical violence, a finding confirmed in the observations of youth programs. Young people explained that they often initiated violence in the belief that such action would protect them against more serious reprisals.

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

797

They also described situations in which violence spun out of control for reasons they could not always identify. The street survey found significant associations between various measures of victimization and perpetration. Young people who had been sexually abused were more likely to have carried a gun in the past 6 months than those who had not been so abused ( p < .01). Those who had been shot were significantly more likely than other respondents to have hit or punched someone, hurt someone badly enough to require medical attention, or threatened someone with a weapon ( p < .05 for all three) in the last 6 months. Causal relationships between victimization and perpetration cannot be established with these data, but the participants in the focus groups described a cycle in which selfassertion, fear, preemptive aggression, and revenge contributed to escalating levels of violence. These descriptions are similar to those found in an analysis of the scripts that 34 motivate serious violent behavior, including homicide, among urban young men. 5. Alcohol and Drug Use Interact With Violence Drugs and alcohol are a regular presence in the lives of many young people in the South Bronx. In the street survey the following was reported: 36% reported trying marijuana and 23% beer or malt liquor. 54% reported never getting high on drugs or alcohol. 27% reported getting high more than once a week, including 21% who got high daily or more frequently. In addition, among those who got high, rates of daily or more frequent use were twice as high for males than for females ( p < .05). In the interviews with incarcerated young men, 41% reported binge drinking of alcohol in the month prior to arrest. 84% had used marijuana. 9% had used crack or cocaine and 2% heroin in the 6 months prior to arrest. In discussions with these young men, many reported that they were high on alcohol or drugs at the time of their arrest. However, few (20%) identified substance abuse as a primary problem after release from jail. Education and employment were viewed as more serious problems. The young women in the focus groups generally did not describe substance abuse as a significant problem for themselves. Violence on the part of their male partners, play fighting, and assaults on the part of peers were not described as having been caused by drugs or alcohol. The one striking exception was a young woman who reported being gang raped by several drunken boys and men. Parental drug or alcohol abuse was viewed as an important cause of violent behavior toward children and youth. Several young women mentioned that in their experience, child abuse, especially sexual abuse, was associated with adult use of alcohol. Respondents also reported that parental drug or alcohol use diminished parents capacity to protect children against harm. The respondents suggested that experiences with violence or abuse in one setting could spill over to other settings. For example, many noted that bad parentsthose who

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

798

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

abused or neglected their children or used drugs or alcohol heavilyoften raised bad children, who mess up their own lives and the lives of other children by fighting, intimidation, and taunting. 6. Weapons Play Both Real and Symbolic Roles in Violence Young people observed that weapons of all sorts are readily available in the South Bronx. Thirty six percent of the street survey respondents reported that they had carried a knife or box cutter (a tool with a razor-sharp blade) and 8% had carried a gun in the previous 6 months, and 17% had threatened someone with such a weapon. Carrying a weapon was not significantly associated with gender, age, or housing status. Victimization was, however, associated with weapons: Those who carried a gun were significantly more likely to have been victims of beatings ( p < .05) or sexual assault( p < .01), and those who used a weapon to threaten someone in the last 6 months were more likely to have been stabbed ( p < .01). Most of the girls in the focus group reported that they had at least one weapon that they used on occasion to protect themselves against violence or to feel safe. Weapons included pepper spray, key rings, knives, box cutters, and, less frequently, guns. Several young women agreed with one participant when she said she would advise any girl to carry something in case she needs to fight. Young women described a strategic approach to making decisions about which weapons to carry or use in different circumstances. Metal objects, for example, could not safely be taken to school, since most schools had metal detectors. Knives and guns increased the risk of stiffer sanctions if the young woman was arrested, so these weapons were often hidden in a place where they could be retrieved if needed. While young women described how weapons made them feel safer and more protected, they also acknowledged that weapons created danger in some circumstances, by either risking more serious criminal charges or provoking higher levels of violence from the victim. 7. Young People See the Police as Both a Cause of and Protection From Violence Police interactions with young people have attracted significant media attention in 35-37 Our studies showed a consistently problemNew York City and elsewhere recently. atic relationship between young people and the police in the South Bronx. Focus group participants acknowledge that police have an important role in reducing crime and protecting the community, whereas focus group participants personal interactions with the police are most often seen to be negative. In the street survey, 16% had been arrested, 12% detained in jail or a juvenile facility, and 6% had been arrested in the last 6 months. Age and gender were not associated with arrest, but a history of sexual assault was ( p < .01). The young women in the focus groups noted that the police were often helpful to old folks and little kids but not to teenagers. The young women consistently described the police as being unhelpful to them when they had problems. One young woman mentioned her reluctance to report someone who was stalking her to the police because she was afraid that the police would exacerbate rather than solve the problem. Several young women reported they occasionally chose not to report criminal activity to the police for

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

799

fear that the police would respond disproportionately, since the police did not respect Black and Latino kids in the South Bronx. The public housing focus group members also mentioned that they believed the primarily White police officers in the South Bronx had negative attitudes toward Black and Hispanic youth. Several advisory board members reported that in their experience, even police officers who grew up in the South Bronx or similar neighborhoods did not necessarily treat young people with respect. 8. Many Young People Take Action to Reduce Violence Young people themselves play a role in preventing or reducing violence. Street survey participants reported that they had stopped an argument (51%) or a fight (45%) in the last 6 months. Focus group participants described strategies to protect themselves against violence: traveling with friends, maintaining mental alertness, and, as previously described, responding to threats forcefully so as to preempt violence. 9. Some Young People Believe That Schools and Community Organizations Could Do More to Reduce Violence As in other communities, schools play a significant role in the lives of young people in the South Bronx. More than three-quarters of both the street survey and incarcerated respondents were enrolled in school in the last year. While most young people in the street survey reported that their school had a violence prevention (84%) or conflict mediation service (82%), the majority did not think much of them. Sixty-six percent rated their schools violence prevention program as fair or poor, and 59% rated the conflict mediation service similarly. It should be noted that the survey did not ask respondents whether they had participated in these activities. Focus group participants were also generally unenthusiastic about school-based programs. One young woman said, Everyone has gone to one of those programs but no one has ever stopped a fight or walked away from a relationship because of the steps they teach. One young woman said she would prefer self-defense classes in which girls learn how to fight. Youth programs play an important role in the lives of young people who participated in these studies. In the street survey, 39% reported that they went to youth programs every day and 20% went twice weekly. Only 21% had never been to a youth program. Time spent at a youth program, however, was not significantly associated with any of the violence perpetration behaviors measured in the survey. Focus group participants often mentioned a staff person at a youth agency as an important source of support and information. They also complained about teasing, taunting, and fighting at the youth programs, a complaint supported by the observations.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PREVENTION This section describes the implications of these findings for the development of community-based efforts to reduce youth violence in low-income urban communities. The recommendations are drawn from the comments of young people in the focus groups, the suggestions of the community advisory board based on its review of the study findings, and the researchers experience in developing and evaluating youth programs. The recommendations can best be seen as hypotheses that require further testing by

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

800

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

intervention research. In addition, since the objective of this work was to understand youth violence in the South Bronx, those in other areas will need to investigate the specific dynamics of violence in their communities. 1. Violence Prevention Programs Need to Strengthen the Specific Protective Factors and Reduce the Specific Risk Factors for Violence That Young People Identify in Their Own Communities The young people in these studies identified several factors that they believe protect them against violence and other factors that increase their vulnerability. These are summarized in Table 4. It is noteworthy that many of the major influences in their livesfamily, peers, school, and neighborhoodwere described as both protective and risk factors. This dual character of what should be the stable foundations of adolescent life make coming of age in low-income urban neighborhoods especially difficult. Other elements such as gangs, weapons, and the police played both positive and negative roles in relation to violence, further complicating the task of safely reaching adulthood. Most interventions to reduce youth violence fall into two categories: hard approaches, such as more police, stiffer sentences for juveniles, and curfews, and soft interventions, such as conflict resolution, after-school programs, sports and recreation 38-43 While each of these approaches programs, and support groups for victims of violence. has a role to play in reducing violence, none seems to adequately address the complexity or pervasiveness of violence described by young people themselves. Moreover, existing programs do not always adequately assess the protective mechanisms young people describe using themselves, nor do they develop specific strategies to reduce the risks they identify (e.g., abusive parents, violent or disrespectful police, a 40 popular culture that sometimes celebrates male violence against women). One solution may lie in helping young people to find safe yet realistic alternatives to the protection that a gang or an accessible weapon is perceived to offer. The participants in these studies identified ways that adults and institutions failed to protect them adequately: Parents warned them against strangers instead of family members or friends; schools taught conflict resolution skills that did not address the scope or magnitude of violence in their lives; community organizations could not always provide them with safe space or consistent adult relationships. If violence prevention programs are to achieve sustainable reductions in violence, they must address the real threats that young people experience, not those imagined by adults. 2. Develop Interventions That Address Both the Shared and the Gender-Specific Needs of Adolescent Males and Females Practitioners in the field now realize that young women need youth programs that 44-46 Other work has focused address their specific needs and create safe spaces for them. on the importance of helping young men to develop attitudes and behaviors that support both positive male identities and gender justice.47 These findings suggest that young men and women share certain important characteristics with respect to violence: high rates of exposure, victimization, and perpetration of various forms of violence; negative attitudes toward the police and school-based violence prevention programs; and feelings of not being respected by adult authorities. However,

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

801

Table 4. Factor

Protective and Risk Factors for Violence Identified by Young People Protective Mechanisms Provide support, encouragement, and safety; set limits Risk Mechanisms Abuse or neglect children; fail to protect against real threats; overprotect, leading to dangerous rebellion; overwhelmed by other responsibilities Tease and taunt, leading to fights; pull into turf or other battles Fail to ensure safe place; fail to provide skills needed to avoid violence

Family/parents

Friends/peers

Provide emotional support; offer safety against other youth Youth programs Offer safer places, relationships with caring adults, and opportunities to try new activities Schools Provide safer space

Gangs

Mass media

Drugs and Alcohol

Police

Weapons

Fail to provide skills needed to avoid violence; fail to engage youth, leading to involvement in risk behavior and risk environments Provide protection Attack some young people; media hype on gangs leads schools and police to overreact, provoking disrespect of youth and possible violence Expose young people to ideas Reinforce disrespect for females; portrays and images outside their own young men of color as enemy, making community them possible targets of violence; reinforce images of romance that increase young womens vulnerability Increase parental abuse or neglect; can lead to sexual victimization; create violence through drug trade; elicit police response threatening community safety Help to reduce crime and violence Harass or assault young people; make victims reluctant to report crime because of fear they will be harassed or response will be excessive Provide feeling of safety, protect Increase threat of retaliation from others; against violence increase risk of serious criminal charges

male and female adolescents experience violence differently: Violence against young women is more associated with intimate relationships than it is for young men, and young womens concepts of romance and heterosexual relationships play a role in their vulnerability to violence. For young people, violence is not a single phenomenon but rather a continuum of behaviors and attitudes. Effective violence prevention programs need to deconstruct the meaning of different forms of violence and address the gender-specific dimensions of each form, sometimes separately for young women and men, at other times integrating the two. In one agency, for example, the goal may be to reduce sexual harassment of young women so they can participate fully in existing activities, whereas in another agency, the goal may be to create specific programs to attract girls. All violence prevention programs

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

802

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

need to help young men and women analyze the role of the media in shaping attitudes on gender and violence and to combat messages that encourage violence against women. 3. Analyze the Specific Causes and Consequences of Different Forms of Violence in the Lives of the Young People Served by a Youth Program in Order to Address Each Adequately Violence was a regular refrain in the lives of most young people who participated in these studies, but it played different roles in the lives of different groups of young people. In our studies, age, gender, and family issues played out differently in different settings. For some of the incarcerated young men, for example, parental drug or alcohol use made it difficult or unsafe for them to return home after release from jail, increasing the chances that they would be exposed to violence on the streets. Parental drug treatment or safe transitional housing may be the best protection against additional violence for this group. Young women in the focus groups reported that they sometimes turned to older male partners to avoid the immaturity of their male peers. Providing access to older female role models may help these young women to assess the risks and benefits of older partners more carefully. Assessing experiences by setting, category of violence, and types of perpetrators and victims can help program planners to map the ecology of youth violence in the specific communities where they work. This approach may help to ground interventions in the circumstances of a particular population or neighborhood and to make them more effective in achieving their objectives. 4. Assist Youth Programs to Offer Young People Meaningful Relationships With Adults Who Care, a Safe Space to Explore Options, and Opportunities to Connect With a Wider World Focus group participants articulated what they wanted from a youth program: stable and caring adults, a safe place to explore new ideas and activities, and opportunities to investigate the world outside their community. Each confirms basic principles of youth 48,49 put together, they provide for a youth program in which young people development; can begin to gain the skills and confidence needed to reduce their risk of violence in the home, school, and community. Some young people find the resources to help them reach adulthood safely within their family or school but, as our data show, others do not. Youth programs have the potential to offer such support to young people. However, a variety of factors made it difficult for some youth programs to achieve this basic goal. In one setting, for example, the lack of structured activities provided few alternatives to the teasing, bullying, and play fighting. Limited resources, changing priorities on the part of public and private funders, and the resulting high staff turnover can make it difficult for youth agencies in low-income urban communities to respond to young peoples needs effectively. Public health professionals can help community-based agencies to strengthen their programs for youth by helping to develop structured, comprehensive interventions; create and sustain an environment in which violence and harassment are not accepted; and establish linkages with other health-promoting organizations inside and outside the community. Equally important, public health workers can help youth organizations to create or join coalitions to advocate for the public resources needed to protect young people

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

803

from violence. These include support for comprehensive youth programs, job training, and preparation for and access to quality secondary and higher education. Finally, we believe that these studies suggest alternative approaches to working with communities to analyze and address problems such as youth violence. Some of the methods we used were as follows: Creating forums in which young people and staff of youth organizations can articulate their perspectives on violence; Involving youth and community residents in planning and interpreting studies; Selecting targeted samples that provide information about various aspects of violence and young people; Analyzing data collected for other purposes to shed light on the topic of interest; Using long-term relationships with the community to gain access to the variety of settings in which youth can be found; and Designing several low-cost, short-term studies to produce useful results within a reasonable time frame. Research of this type is not a substitute for more systematic or longitudinal studies. It does, however, offer the opportunity to understand a problem from the perspectives of those it affects and to engage key stakeholders in creating solutions to one of the most pressing social problems facing low-income urban communities.

References

1. Fingerhut LA, Ingram DD, Feldman JJ: Homicide rates among US teenagers and young adults: Differences by mechanism, level of urbanization, race and sex, 1987 through 1995. JAMA 280:423-427, 1998. 2. The Commonwealth Fund: The Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls. New York, Louis Harris and Associates, 1997. 3. Kann L, Kinchen SA, Ross JG, et al: Youth risk behavior surveillanceUnited States, 1997 (CDC Surveillance Summary, August 14, 1998). MMWR 47(SS-3):1-31, 1998. 4. Jenkins EJ, Bell CC: Exposure and response to community violence among children and adolescents, in Osofsky JD (ed.): Children in a Violent Society. New York, Guilford Press, 1997, pp. 9-31. 5. Bell CC, Jenkins EJ: Community violence and children on Chicagos southside. Psychiatry 56:46-54, 1993. 6. Osofsky JD, Wewers S, Hann DM, Fick AC: Chronic community violence: What is happening to our children? Psychiatry 56:7-21, 1993. 7. Martinez P, Richters J: The NIMH community violence project II: Childrens distress symptoms associated with violence exposure. Psychiatry 56:23-35, 1993. 8. Schubiner H, Scott R, Tzelepis A: Exposure to violence among inner-city youth. J Adolesc Health 14:214-219, 1993. 9. Schwab-Stone ME, Ayers TS, Kasprow W, Voyce C, Barone C, Shriver T, Weissberg RP: No safe haven: A study of violence exposure in an urban community. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:1343-1352, 1995. 10. Sheehan K, DiCara JA, LeBailly S, Christolffel KK: Childrens exposure to violence in an urban setting. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med 151:502-504, 1997. 11. Berman SL, Kurtines WM, Silverman WK, Serafini LT: The impact of exposure to crime and violence on urban youth. Am J Orthopsychiatry 66:329-336, 1996.

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

804

Health Education & Behavior (December 1999)

12. DuRant RH, Getts A, Cadenhead C, Emans SJ, Woods ER: Exposure to violence and victimization and depression, hopelessness, and purpose in life among adolescents living in and around public housing. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 16:233-237, 1995. 13. Freeman LN, Mokros H, Poznanski EO: Violent events reported by normal urban school-aged children: Characteristics and depression correlates. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:419-423, 1993. 14. OKeefe M: Adolescents exposure to community and school violence: Prevalence and behavioral correlates. J Adolesc Health 20:368-376, 1997. 15. New York City Department of City Planning: 1997 Annual Report on Social Indicators (NY DCP#98-16). New York, New York City Department of City Planning, 1998. 16. United Hospital Fund: New York City Community Health Atlas 1994. New York, United Hospital Fund, 1994. 17. New York City Department of Health: Summary of reportable diseases and conditions, 1996. City Health Information 17:1-28, 1998. 18. Morales I (director): Palante Siempre Palante: The Young Lords Party [Film]. New York, Association of Hispanic Arts, 1996. Available from Association of Hispanic Arts, 173 East 116th Street, New York, NY 10026. 19. Kozol J: Amazing Grace: The Lives of Children and the Conscience of a Nation. New York, Crown Books, 1995. 20. Hall T: A South Bronx very different from the cliche. The New York Times, February 14, 1999, sec. 11, pp. 1, 6. 21. Walsh J: Stories of Renewal: Community Building and the Future of Urban America. New York, Rockefeller Foundation, 1997. 22. Foley D, Epstein R: Zone offense. City Limits 21(9):10-11, 1996. 23. Patton MQ: Utilization-Focused Research: The New Century Text (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 1997. 24. Gilbert N (ed.): Researching Social Life. Newbury Park, CA, Sage, 1993. 25. Kim S, Kibel B, Williams C, Helpler N: Evaluating the success of community-based substance-abuse prevention efforts: Blending old and new approaches and methods (MD DHHS Pub. No [SMA] 96-3110), in Bayer A-H, Brisbane FL, Ramirez A (eds.): Advanced Methodological Issues in Culturally Competent Evaluation for Substance Abuse Prevention. Rockville, MD, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, 1996, pp. 159-182. 26. Fawcett SB, Paine-Andrews A, Francisco VT, et al: Empowering community health initiatives through evaluation, in Fetterman D, Kaftarian SJ, Wandersman A (eds.): Empowerment Evaluation Knowledge and Tools for Self-Assessment and Accountability. Thousand Oaks, CA, 1996, pp. 2161-2187. 27. Youth Force: Report on Boogie Down Survey. Unpublished report, 1998. 28. Hunter College Center on AIDS, Drugs and Community Health: Health Link: Description of a Model Program to Reduce Substance Abuse and Recidivism. New York, Hunter College Center on AIDS, Drugs and Community Health, 1997. 29. Freudenberg N, Wilets I, Greene M, Richie B: Linking women in jail to community services: Factors associated with rearrest and retention of drug-using women following release from jail. JAMWA 53:89-93, 1998. 30. Ellickson P, Saner H, McGuigan K: Profiles of violent youth: Substance abuse and other concurrent problems. Am J Public Health 87:985-991, 1997. 31. Chesney-Lind M: Girls, Delinquency and Juvenile Justice. Pacific Grove, CA, Brooks/Cole, 1995. 32. Girls, Inc., Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention: Prevention and Parity: Girls in Juvenile Justice. New York, Girls, Inc., 1996. 33. Abma J, Sonenstein FL: Teenage Sexual Behavior and Contraceptive Use: An Update. Paper presented to the Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998.

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Freudenberg et al. / Role of Violence

805

34. Wilkinson DL, Fagan J: The role of firearm scripts: The dynamics of gun events among adolescent males. Law and Contemporary Problems 59:55-89, 1996. 35. Amnesty International: USA: Police Brutality and Excessive Force in the New York City Police Department. New York, Amnesty International, 1996. 36. Herbert B: Whats going on? The New York Times, February 14, 1999, p. 13. 37. Yardley J: In two minority neighborhoods, residents see a pattern of hostile street searches. The New York Times, March 29, 1999, p. B3. 38. Sherman LW, Gottfredson D, MacKenzie D, Eck J, Reuter P, Bushway S: Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesnt and Whats Promising? Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Justice, 1997. 39. Montgomery IM, Torbet PM, Malloy DA, Adamcik LP, Toner MJ, Andrews J: What Works: Promising Interventions in Juvenile Justice. Washington, DC, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 1994. 40. Greene MB: Youth violence in the city: The role of educational interventions. Health Educ Behav 25:175-193, 1998. 41. Wilson-Brewer R: Peer violence prevention programs in middle and high schools. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews 6:233-250, 1995. 42. Doucette-Gates A, Thompson N, Dawkins N: Final Report: Steps to Successful Implementation of Youth Violence Prevention Programs. Atlanta, GA, Macro International, 1996. 43. Thomas SB, Leite B, Duncan T: Breaking the cycle of violence among youth living in metropolitan Atlanta: A case history of Kids Alive and Loved. Health Educ Behav 25:160-174, 1998. 44. Pastor J, McCormick J, Fine M: Makin homes: An urban girl thing, in Ledbeater BJ, Way N (eds.): Urban Girls: Resisting Stereotypes, Creating Identities. New York, New York University Press, 1996, pp. 15-32. 45. Acoca L, Austin J: The California GirlsStory. San Francisco, National Council on Crime and Delinquency, 1998. 46. Acoca L: Inside/outside: The violation of American girls at home, on the streets and in the juvenile justice system. Crime & Delinquency 44:561-589, 1998. 47. Fine M, Genovese T, Ingersoll S, Macpherson P, Roberts R: Insisting on innocence: Accounts of accountability by abusive men, in Lykes M, Banuazzi A, Liem R, Morris M, Albee G (eds.): Myths about the Powerless: Contesting Social Inequalities. Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1996, pp. 128-154. 48. Jessor R: Successful adolescent development among youth in high risk settings. Am Psychol 48:117-126, 1993. 49. Dryfoos J: Safe Passage: Making It Through Adolescence in a Risky Society: What Parents, Schools and Communities Can Do. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Downloaded from http://heb.sagepub.com at HUNTER COLLEGE LIB on February 10, 2010

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

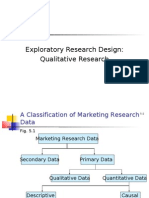

- Exploratory Research DesignDocument23 pagesExploratory Research DesignimadPas encore d'évaluation

- International Horse Park Feasability StudyDocument44 pagesInternational Horse Park Feasability Studymhanna4485Pas encore d'évaluation

- Special Education - FullDocument15 pagesSpecial Education - FullTeguh ImsanPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ProposalDocument14 pagesResearch Proposalapi-462457806Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ib Business Management Exam Style Marketing QuestionsDocument6 pagesIb Business Management Exam Style Marketing Questionsalex.dumphy777Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nampila. MIT. Dev of A Computer-Assisted School Info System For Namibian SchoolsDocument141 pagesNampila. MIT. Dev of A Computer-Assisted School Info System For Namibian SchoolsMarcos Perez100% (1)

- PR 1 Lecture 2Document29 pagesPR 1 Lecture 2Mabell MingoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Research ProcessDocument5 pagesConsumer Research ProcessGirija mirjePas encore d'évaluation

- Listening To Students Customer Journey Mapping at Birmingham City University Library and Learning ResourcesDocument18 pagesListening To Students Customer Journey Mapping at Birmingham City University Library and Learning ResourcesThi Viet Hoa DangPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Conduct A Focus Group Discussion (FGD) - Methodological ManualDocument18 pagesHow To Conduct A Focus Group Discussion (FGD) - Methodological ManualRaj'z KingzterPas encore d'évaluation

- The Challenges in The Provision of Counselling Services in Secondary Schools in TanzaniaDocument22 pagesThe Challenges in The Provision of Counselling Services in Secondary Schools in TanzaniaTubers ProPas encore d'évaluation

- Focus Groups Theory and PracticeDocument4 pagesFocus Groups Theory and PracticeJosé Félix Salazar CrucesPas encore d'évaluation

- ENTREP - Module 2 - Identifying and Recognizing OpportunitiesDocument15 pagesENTREP - Module 2 - Identifying and Recognizing OpportunitiesIsaiah AlduesoPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Research Methods BRMDocument29 pagesBusiness Research Methods BRMNivedh VijayakrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sex Education: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationDocument15 pagesSex Education: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationNevvi WibellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Main Doc. MJMC2A (SPARSH TAPISH AND ALANKRITA)Document13 pagesResearch Main Doc. MJMC2A (SPARSH TAPISH AND ALANKRITA)Alankrita TiwariPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Conduct A Successful Focus Group Discussion - SocialCopsDocument9 pagesHow To Conduct A Successful Focus Group Discussion - SocialCopsLasantha WickremesooriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Travel and Toursim Paper 2Document3 pagesTravel and Toursim Paper 2maevaPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Opportunity and Generating IdeasDocument37 pagesBusiness Opportunity and Generating Ideasillya amyraPas encore d'évaluation

- Voice of Customer Robert Cooper PDFDocument13 pagesVoice of Customer Robert Cooper PDFBiYa KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Yougov The Social Work ProfessionDocument68 pagesYougov The Social Work ProfessionKunal JaiswalPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Research Written ReportDocument9 pagesMarketing Research Written ReportAda Araña DiocenaPas encore d'évaluation

- FGD Definition 24th May 11.32PMDocument2 pagesFGD Definition 24th May 11.32PMFeisal FeyzePas encore d'évaluation

- Studying North Korea Through North Korean MigrantsDocument17 pagesStudying North Korea Through North Korean MigrantsrameenPas encore d'évaluation

- MDSX County NAACP Health Committee - HES Report 11 - 2019 - FinalDocument29 pagesMDSX County NAACP Health Committee - HES Report 11 - 2019 - FinalCassandra DayPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 Business Ideas & OpportunitiesDocument20 pagesChapter 2 Business Ideas & OpportunitiesMamaru Nibret DesyalewPas encore d'évaluation

- Cia 1Document9 pagesCia 1kumar.vinod183Pas encore d'évaluation

- VRTS114 - PPT X PRELIM EXAMDocument106 pagesVRTS114 - PPT X PRELIM EXAMJPPas encore d'évaluation

- Women in STEM in Egypt (British Council Booklet - 2021)Document36 pagesWomen in STEM in Egypt (British Council Booklet - 2021)Pivot Global EducationPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrep 12 q1 m4 Market Research 011507Document19 pagesEntrep 12 q1 m4 Market Research 011507Rina BaldosanoPas encore d'évaluation