Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Kangaroo Mother Care - A Research Paper

Transféré par

Nathaniel BroylesCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Kangaroo Mother Care - A Research Paper

Transféré par

Nathaniel BroylesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Kangaroo Mother Care: An Argument for the Adoption of a Comprehensive KMC Program in U.S.

Hospitals

By Nathaniel B. Broyles

PSY 281 - Developmental Psychology I Prof. Elizabeth Geiling August 3, 2011

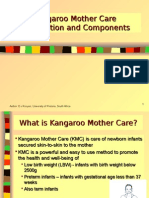

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) is a technique wherein newborns are carried directly against the skin of the mother. The practice was started in 1978 in Bogota (Colombia) in response to overcrowding and insufficient resources in neonatal intensive care units associated with high morbidity and mortality among low-birthweight infants. (Charpak, 514) It is practiced in low, middle, and high-income countries but is most prevalent in developing countries that do not have access to the same level of health care and medicine found in countries like the United States. It is primarily practiced because there is very little cost associated with its practice, which makes it affordable in a country where there may only be one trained medical doctor serving the needs of the equivalent of a mid-sized city in a more developed nation. Surprisingly, however, those infants who are getting by on KMC may be better off in some ways than those who are cared for in what we envision in America as normal.

Dr. Edgar Rey Sanabria founded the KMC practice in 1978 in order to address the critical lack of incubators, cross-infections, and infant abandonment at his hospital. The overcrowding and insufficient resources in Dr. Sanabrias neonatal intensive care unit led to a high morbidity and mortality rate among low-birthweight infants. The intervention that he developed involved continuous skin-to-skin care between infant and mother, exclusive breastfeeding, and early home discharge in the kangaroo position. (Charpak, 514)The theory behind KMC has its basis in neuroscience and operates on the premise that mother and infant are a dyad that should not be separated. Kangaroo refers to the means by which some marsupials care for their young, wherein the infant is kept warm in a maternal pouch and close to the breasts for unlimited feeding. (Ali, 156) Brain development in infants requires maternal sensory stimulation based on skin-to-skin contact and the incubator strips that stimulation away, leading to poorer brain development.

(Etika, 220) In many cases, incubator treatment is unnecessary for the health and survival of the infant but is still used as a matter of course.

Low-birthweight (LBW) infants are a major problem all over the world and not solely in less-developed countries. In developing countries, however, approximately 30% of all neonatal mortality is directly related to LBW. It has become common practice in hospitals around the world to treat LBW infants in incubators or with radiant warmers. In developing countries, these practices are often extremely difficult to implement due to the high costs of the equipment, difficulty in maintenance and repair of that equipment, unreliable power supply, and a lack of trained staff. (Ali, 156) It was an innovative and creative solution to a critical problem. The solution also had unexpected benefits that had researchers flocking to Bogota to learn this new technique.

Later testing to determine whether or not KMC was truly a viable alternative to what we think of as conventional care for LBW infants proved that, in many ways, KMC is a better alternative, provided that there are no other barriers than LBW for the infant to overcome. For instance, babies born prematurely would need more help than KMC can provide in order to develop physically enough that KMC becomes an option for care. When comparing conventional treatment of LBW infants with those receiving KMC, as was done from March 2006 to September 2007 in a randomized controlled trial (Ali, 159), the KMC infants demonstrated significantly higher weight gain during the course of their hospital stay. It is theorized that this is due to reduced energy requirements that the infant was able to direct towards growth. There was also a large reduction in respiratory rate and an increase in oxygen saturation in the infants

receiving KMC. Since both processes are gravity dependent, the upright position utilized in KMC practice seems likely to be a factor in explaining those results. Since placing an infant in skin-to-skin contact with their mother underneath a blouse or shirt inevitably creates an insulating effect, the KMC infants showed very few instances of hypothermia and a higher rectal temperature than those receiving conventional care. Incidences of infection were also significantly higher in the infants receiving more conventional care. (Ali, 160)

If the physical differences between LBW newborns receiving conventional care versus those being given KMC were not astounding enough, studies show that KMC has an effect on the neurobehavioral responses of infants. In fact, there is a significant difference in neurobehavioral development between infants receiving radiant warmer or incubator care and those receiving KMC. (Rebecca, 54) In one study, performed from June 30, 2008 through August 5, 2008, the physiological differences were observed through electronic thermometer and monitors. A Modified Brazelton Behavioral Assessment Scale was used to judge the neurobehavioral state of the infants. It should also be noted that this study was aimed at full-term newborns that were not classified as LBW. When observing the physiological state of both groups of infants, it was seen that both fell into what could be classed as normal parameters. It was in the neurobehavioral results that significant differences were found. The mean behavioral response score of the radiant warmer care infant was 5.6500 and the KMC infant mean was 5.9500. That is a differential that certainly cannot be ignored and explained away as an anomaly.

Although originally intended as an alternative practice in lower income settings, it is clear that KMC can also be utilized to great effect in high-technology environments also. Where KMC

is practiced in those more wealthy areas, the more traditional treatment tends to be supplemented by KMC sessions of one to a few hours for intermittent periods. (Nyqvist, 812) Many of the same effects noted in those LBW infants whose mothers utilize KMC are found even in those babies fortunate enough to be born in a more high-tech environment and receive intermittent KMC. In addition to those positive effects previously mentioned, infants experience: a decrease in the pain response for painful procedures, lower infant cortisol, and physiological parameters tend to be more stable during transport when KMC is used by parents (even hospital staff if the childs parents give permission). (Nyqvist, 813)

Other common benefits of KMC are psychosocial in nature. For instance, when engaging in KMC there is a more rapid healing from parental crisis reactions after the birth of a pre-term or LBW baby. In addition, recovery post-partum depression in new mothers is increased over those mothers who engage only in more conventional care of their infants and feel less stress associated with their newborn. Even the intermittent KMC usually practiced in more affluent hospitals results in a higher breastfeeding rate, longer durations of breastfeeding, and a higher proportion of exclusive breastfeeding while in the hospital and through follow-up care. (Nyqvist, 813)

KMC is not relegated to the sole domain of mothers as it can be equally important, even beneficial, for the father to also engage in the skin-to-skin contact of KMC. The interaction of the father is especially beneficial once mother and infant have been discharged from the hospital and are in their home environment. Unlike the marsupials whose name we use to characterize this particular method of infant care, humans do not have a belly pouch to carry an infant around

in and so mothers will, inevitably, need help in order to provide continuous KMC. Although the father cannot breastfeed the infant, the skin-to-skin contact provides much the same benefit that would be received from the mother. In fact, studies show that the fathers involvement in more direct KMC carries with it a greater sensitivity by the father, a better perception of the child by the father, and an all-around better home environment. It is hypothesized that this sense of coresponsibility and greater involvement happens the first time that the carrying position is used. (Tessier, 1448) Fathers who engaged in more traditional care may also develop those same feelings but it is more likely that KMC fathers will form those deeper connections more quickly.

Whereas the more traditional high-tech care found in Western societies, and which have become the norm around the world, can often cost tens of thousands of dollars in equipment and training, the implementation of KMC has no such costs associated with it. In fact, the only costs associated with KMC is for the training of the hospital personnel who would be responsible for educating new mothers and fathers on how to properly implement their personal KMC program and, perhaps, some literature to be printed and distributed to those same parents. There would be tremendous cost savings for the parents, too. Buying formula can be extremely expensive but breastfeeding is, essentially, free. Caring for a newborn can be a financial burden with all of the associated costs but paying for something that nature provides should not be one of them.

In 2010, a proposal was made to revise the World Health Organizations practical guide to include updated information and extensive revision. That proposal includes an exhaustive argument for the WHO to strongly endorse more comprehensive KMC practice worldwide. (Nyqvist, 825) All of the available evidence supports KMC as not just an alternative treatment

for LBW infants in low-income areas of the world but as an important component infant development. While low-income hospitals may, out of necessity, have KMC as the totality of infant care, KMC has proven to be equally as effective in a high-tech environment. While it must be acknowledged that KMC cannot completely replace all of the neonatal care that infants deserve, especially when the treatments are available, KMC should be universally practiced and taught to mothers in every hospital around the world. The benefits of KMC are tangible and cannot be denied as advantageous both to the dyad of mother and infant but to the entire family unit as well.

Works Cited Ali, S., Sharma, J., Sharma, R., & Alam, S. (2009). Kangaroo Mother Care as compared to conventional care for low birth weight babies. Dicle Medical Journal / Dicle Tip Dergisi, 36(3), 155-160. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Charpak, N., Ruiz, Juan G., Zupan, J., Cattaneo, A., Figueroa, Z., Tessier, R., Cristo., M., Anderson, G., Ludington, S., Mendoza, S., Mokhachane, M., Worku, B. (2005) Kangaroo Mother Care: 25 years after. Acta Paediatrica, 94(5), 514-522. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Etika, R., Roeslani, R. D., Alasiry, E., Endyarni, B., & Bergman, N. J. (2009). "HUMANITY FIRST, TECHNOLOGY SECOND" REDUCING INFANT MORTALITY RATE WITH KANGAROO MOTHER CARE: PRACTICAL EVIDENCE FROM SOUTH AFRICA. Folia Medica Indonesiana, 45(3), 219-224. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Rebecca, J., Nayak, S., & Paul, S. (2011). Comparison of Radiant Warmer Care and Kangaroo Mother Care Shortly after Birth on the Neurobehavioral Responses of the Newborn. Journal of South Asian Federation of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 3(1), 53-55. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Nyqvist, K. H., Anderson, G. C., Bergman, N. N., Cattaneo, A. A., Charpak, N. N., Davanzo, R. R., & ... Widstrm, A. M. (2010). State of the art and recommendationsKangaroo mother care: application in a high-tech environment. Acta Paediatrica, 99(6), 812-819. doi:10.1111/j.16512227.2010.01794.x Nyqvist, K. H., Anderson, G. C., Bergman, N. N., Cattaneo, A. A., Charpak, N. N., Davanzo, R. R., & ... Widstrm, A. M. (2010). Towards universal Kangaroo Mother Care: recommendations and report from the First European conference and Seventh International Workshop on Kangaroo Mother Care. Acta Paediatrica, 99(6), 820-826. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01787.x Tessier, R. R., Charpak, N. N., Giron, M. M., Cristo, M. M., de Calume, Z. F., & Ruiz-Pelez, J. G. (2009). Kangaroo Mother Care, home environment and father involvement in the first year of life: a randomized controlled study. Acta Paediatrica, 98(9), 1444-1450. doi:10.1111/j.16512227.2009.01370.x

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Serenity RPG Firefly Role Playing Game PDFDocument225 pagesSerenity RPG Firefly Role Playing Game PDFNathaniel Broyles67% (3)

- Dark HuntersDocument204 pagesDark HuntersNathaniel Broyles100% (3)

- John Carter of Mars QuickstartDocument27 pagesJohn Carter of Mars QuickstartCarl Dettlinger100% (1)

- Converting 2e Monsters Into 5EDocument10 pagesConverting 2e Monsters Into 5ENathaniel BroylesPas encore d'évaluation

- Editable Pathfinder Character SheetDocument2 pagesEditable Pathfinder Character SheetTimothie Spearman100% (1)

- Childhood and Adolescence: Voyages in Development, 7e: Chapter 7: Infancy: Social andDocument60 pagesChildhood and Adolescence: Voyages in Development, 7e: Chapter 7: Infancy: Social andNUR HUMAIRA ROSLIPas encore d'évaluation

- Pharaoh PDFDocument55 pagesPharaoh PDFFrederic Sierra50% (2)

- The Savage World of Flash Gordon Combat Options PDFDocument2 pagesThe Savage World of Flash Gordon Combat Options PDFNathaniel Broyles100% (1)

- Handbook of Parenting. - Vol 4 (Social Conditions, Applied ParentingDocument444 pagesHandbook of Parenting. - Vol 4 (Social Conditions, Applied ParentingEdi Hendri MPas encore d'évaluation

- Foster Social, Intellectual, Creative and Emotional Development of ChildrenDocument29 pagesFoster Social, Intellectual, Creative and Emotional Development of Childrenbing masturPas encore d'évaluation

- Fading Suns - Core Rulebook Second EditionDocument315 pagesFading Suns - Core Rulebook Second EditionLilLuvLip100% (5)

- BCPC 2022 Accomplishment ReportDocument2 pagesBCPC 2022 Accomplishment ReportBpv Barangay100% (8)

- Social Emotional DevelopmentDocument48 pagesSocial Emotional DevelopmentDinushika Madhubhashini100% (1)

- HP Family MattersDocument187 pagesHP Family MattersNathaniel Broyles0% (3)

- Lesson-Plan-Kangaroo-Mother CareDocument18 pagesLesson-Plan-Kangaroo-Mother CareG.Sangeetha bnch100% (1)

- Hubungan Preeklamsi Berat Dengan Kelahiran Preterm Di Rumah Sakit Umum Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat 2013Document10 pagesHubungan Preeklamsi Berat Dengan Kelahiran Preterm Di Rumah Sakit Umum Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat 2013Vera Andri YaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Kangaroo Mother Care 25 Years AfterDocument9 pagesKangaroo Mother Care 25 Years Afteraisyah nurfaidahPas encore d'évaluation

- DELA PEÑA - Journal Reading - 03-06-2022Document2 pagesDELA PEÑA - Journal Reading - 03-06-2022Mark Teofilo Dela PeñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison Between Kangaroo Mother Care and Traditional Incubator Care 1Document7 pagesComparison Between Kangaroo Mother Care and Traditional Incubator Care 1Gladys vidzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Literature Kangaroo Mother CareDocument5 pagesReview of Literature Kangaroo Mother Caregw1m2qtf100% (1)

- Skin-to-Skin Care For Term and Preterm Infants in The Neonatal ICUDocument6 pagesSkin-to-Skin Care For Term and Preterm Infants in The Neonatal ICUGabyBffPas encore d'évaluation

- Kangaroo Mother Care Brief FinalDocument2 pagesKangaroo Mother Care Brief FinalSirju RanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Current PracticeDocument4 pagesCurrent PracticeAmelia ArnisPas encore d'évaluation

- International Journal of Health Sciences and ResearchDocument7 pagesInternational Journal of Health Sciences and ResearchElis FatmayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief Resume of The Intended Work: "The Nation Walks On The Feet of Little Children."Document11 pagesBrief Resume of The Intended Work: "The Nation Walks On The Feet of Little Children."sr.kumariPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis On BreastfeedingDocument4 pagesThesis On Breastfeedingppxohvhkd100% (2)

- Brauchle - Ebp Synthesis Paper - Nur 332Document17 pagesBrauchle - Ebp Synthesis Paper - Nur 332api-405374041Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On Neonatal NursingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Neonatal Nursinggvxphmm8100% (1)

- Neonatal Dissertation TopicsDocument8 pagesNeonatal Dissertation TopicsPaperWritersCollegeSingapore100% (1)

- Breastfeeding Dissertation TopicsDocument8 pagesBreastfeeding Dissertation TopicsBuyACollegePaperOnlineMilwaukee100% (1)

- Nur 403 Tni PaperDocument11 pagesNur 403 Tni Paperapi-369824515Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On Exclusive Breastfeeding PDFDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Exclusive Breastfeeding PDFegtwfsaf100% (1)

- Examples of Breastfeeding DissertationDocument5 pagesExamples of Breastfeeding DissertationWriteMyPaperForMeIn3HoursCanada100% (1)

- Dissertation On Kangaroo Mother CareDocument4 pagesDissertation On Kangaroo Mother CareWriteMyPaperApaStyleUK100% (1)

- Benefits of Skin-To Skin Contact During The Neonatal PeriodDocument3 pagesBenefits of Skin-To Skin Contact During The Neonatal PeriodEMDR Uruguay NiñosPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Topics On BreastfeedingDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Topics On Breastfeedingafnhemzabfueaa100% (1)

- Provision of Kangaroo Mother Care: Supportive Factors and Barriers Perceived by ParentsDocument9 pagesProvision of Kangaroo Mother Care: Supportive Factors and Barriers Perceived by ParentsGladys Barzola CerrónPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On Exclusive BreastfeedingDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Exclusive Breastfeedingmadywedykul2100% (1)

- Thesis Statement Breastfeeding in PublicDocument5 pagesThesis Statement Breastfeeding in Publicafkntwbla100% (2)

- Neonatal Research PaperDocument5 pagesNeonatal Research Paperkrqovxbnd100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S1355184121001769 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S1355184121001769 MainIrene RubioPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On Pregnancy and ChildbirthDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Pregnancy and Childbirthnywxluvkg100% (1)

- Literature Review Kangaroo Mother CareDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Kangaroo Mother CareafdtuwxrbPas encore d'évaluation

- Nresearch PaperDocument13 pagesNresearch Paperapi-399638162Pas encore d'évaluation

- Metode KanguruDocument9 pagesMetode KanguruSyariifahhPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Literature On Care of Low Birth Weight BabiesDocument6 pagesReview of Literature On Care of Low Birth Weight Babiesc5rnbv5rPas encore d'évaluation

- 'Kangaroo Mother Care' To Prevent Neonatal Deaths Due To Preterm Birth ComplicationsDocument11 pages'Kangaroo Mother Care' To Prevent Neonatal Deaths Due To Preterm Birth ComplicationsLuzdelpilar RcPas encore d'évaluation

- Metode Kangguru BBLRDocument5 pagesMetode Kangguru BBLRdiana seviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal AnakDocument11 pagesJurnal AnakShinta Andi SarasatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Assess The Knowledge and Practice of Mothers Regarding Kangaroo Care With A View To Develop Health Education Module On Kangaroo CareDocument9 pagesAssess The Knowledge and Practice of Mothers Regarding Kangaroo Care With A View To Develop Health Education Module On Kangaroo CareIJARSCT JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Breastfeeding Thesis PaperDocument4 pagesBreastfeeding Thesis PaperBestCustomPaperWritingServiceCanada100% (2)

- Educacion A Familias Niños TQTDocument12 pagesEducacion A Familias Niños TQTPauli VelásquezPas encore d'évaluation

- 107 Lec Finals 3RD LessonDocument8 pages107 Lec Finals 3RD LessonChona CastorPas encore d'évaluation

- Nresearch PaperDocument14 pagesNresearch Paperapi-400982160Pas encore d'évaluation

- Northwest Mothers Milk BankDocument12 pagesNorthwest Mothers Milk Bankapi-241882918Pas encore d'évaluation

- Zaylaa 2018Document15 pagesZaylaa 2018Daniel MalpartidaPas encore d'évaluation

- A. KMC Introduction, Components & BenefitsDocument25 pagesA. KMC Introduction, Components & BenefitssantojuliansyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Hasni B.ingDocument9 pagesJurnal Hasni B.ingrasdianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Breastfeeding Benefits Research PaperDocument8 pagesBreastfeeding Benefits Research Paperafnhdcebalreda100% (1)

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaDocument16 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaesakkiammalPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Literature Related To Kangaroo Mother CareDocument8 pagesReview of Literature Related To Kangaroo Mother Carec5swkkcnPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Kangaroo Mother Care On The Likelihood of Breastfeeding From Birth Up To 6 Months of Age: A Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesEffect of Kangaroo Mother Care On The Likelihood of Breastfeeding From Birth Up To 6 Months of Age: A Meta-AnalysispurplemmyPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review Breast FeedingDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Breast Feedings1bivapilyn2100% (2)

- Misamis University College of Nursing and Midwifery Ozamiz CityDocument12 pagesMisamis University College of Nursing and Midwifery Ozamiz CityDENMARKPas encore d'évaluation

- MODULE 3: Kangaroo Mother CareDocument11 pagesMODULE 3: Kangaroo Mother CareKristina BurburanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pacifier and Bottle Nipples: The Targets For Poor Breastfeeding OutcomesDocument3 pagesPacifier and Bottle Nipples: The Targets For Poor Breastfeeding Outcomesbeleg100% (1)

- Artificial Womb To Maintain Fluidfilled LungsDocument2 pagesArtificial Womb To Maintain Fluidfilled LungsHas SimPas encore d'évaluation

- Neonatology Thesis TopicsDocument7 pagesNeonatology Thesis Topicspwqlnolkd100% (1)

- Association Between Rooming-In Policy and Neonatal HyperbilirubinemiaDocument6 pagesAssociation Between Rooming-In Policy and Neonatal HyperbilirubinemiaRissa IchaPas encore d'évaluation

- Zainab ProjectDocument35 pagesZainab ProjectOpeyemi JamalPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Paper EthicsDocument9 pagesFinal Paper Ethicsapi-726698459Pas encore d'évaluation

- Breast Feeding Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesBreast Feeding Literature Reviewgatewivojez3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Water Birth Research PaperDocument6 pagesWater Birth Research Papergw10ka6s100% (1)

- Strategies For Feeding The Preterm Infant: ReviewDocument10 pagesStrategies For Feeding The Preterm Infant: ReviewSanjuy GzzPas encore d'évaluation

- Intensive Care of The Neonatal FoalDocument32 pagesIntensive Care of The Neonatal FoalAristoteles Esteban Cine VelazquezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Preemie Parents' Companion: The Essential Guide to Caring for Your Premature Baby in the Hospital, at Home, and Through the First YearsD'EverandThe Preemie Parents' Companion: The Essential Guide to Caring for Your Premature Baby in the Hospital, at Home, and Through the First YearsPas encore d'évaluation

- Official RT NamesDocument12 pagesOfficial RT NamesAnonymous 2UAIvU04FPas encore d'évaluation

- A Reaction Paper To "Genetic Encores: The Ethics of Human Cloning"Document4 pagesA Reaction Paper To "Genetic Encores: The Ethics of Human Cloning"Nathaniel Broyles100% (3)

- WH40K RPG Deathwatch Rites of BattleDocument257 pagesWH40K RPG Deathwatch Rites of BattleJared Meyers92% (26)

- A Reaction Paper On The Amish Rite of Passage: RumspringaDocument4 pagesA Reaction Paper On The Amish Rite of Passage: RumspringaNathaniel Broyles100% (1)

- Book Review - A Child Called ItDocument6 pagesBook Review - A Child Called ItNathaniel BroylesPas encore d'évaluation

- A Reflection On Platonic ThoughtDocument8 pagesA Reflection On Platonic ThoughtNathaniel BroylesPas encore d'évaluation

- Prevalence and Factors Hindering First Time Mothers From Exclusively Breast Feeding in Kyabugimbi Health Centre IV, Bushenyi District UgandaDocument11 pagesPrevalence and Factors Hindering First Time Mothers From Exclusively Breast Feeding in Kyabugimbi Health Centre IV, Bushenyi District UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONPas encore d'évaluation

- Metro Manila Developmental Screening Test MMDSTDocument20 pagesMetro Manila Developmental Screening Test MMDSTMellePas encore d'évaluation

- (2014) Positive ParentingDocument9 pages(2014) Positive ParentingDummy MummyPas encore d'évaluation

- STEM-Report As On 31.05.2022 at 9.00 AM: Samagra Shiksha - KanniyakumariDocument31 pagesSTEM-Report As On 31.05.2022 at 9.00 AM: Samagra Shiksha - KanniyakumariAshwanth DevPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument383 pagesUntitledMicah Barroa BernalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Sina-On, Glennie - Critical Essay - Final Paper For HE 290ADocument9 pagesSina-On, Glennie - Critical Essay - Final Paper For HE 290AGlennieMarieSina-onPas encore d'évaluation

- Welcome To Seminar: Dr. Sharmin Afroze Dr. Amlendra Kumar YadavDocument20 pagesWelcome To Seminar: Dr. Sharmin Afroze Dr. Amlendra Kumar YadaviiTzZ CaRfTPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature and Arts A-18Document16 pagesLiterature and Arts A-18Rebecca LôboPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Labour in The PhilippinesDocument1 pageChild Labour in The PhilippinesmauiPas encore d'évaluation

- Resilience in ChildrenDocument27 pagesResilience in Childrenapi-383927705Pas encore d'évaluation

- EARLY DIAGNOSIS - CEREBRAL PALSY Prechtl's General Movements AssessmentDocument4 pagesEARLY DIAGNOSIS - CEREBRAL PALSY Prechtl's General Movements AssessmentMaria Del Mar Marulanda GrizalesPas encore d'évaluation

- SP Final EssayDocument12 pagesSP Final Essayapi-660405105Pas encore d'évaluation

- Growth & DevtDocument15 pagesGrowth & DevtKATE LAWRENCE BITANTOSPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1 - Introduction To Human DevelopmentDocument24 pagesLesson 1 - Introduction To Human DevelopmentMarjorie Emanel CullaPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2-The Stages of Development and Developmental TasksDocument2 pagesModule 2-The Stages of Development and Developmental TasksdonixPas encore d'évaluation

- Prenatal PeriodDocument4 pagesPrenatal PeriodMark Kenneth Cape CoronadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Proper Positioning of Babies For BreastfeedingDocument3 pagesProper Positioning of Babies For BreastfeedingKathleen ColinioPas encore d'évaluation

- Notebook Lesson XL by SlidesgoDocument20 pagesNotebook Lesson XL by SlidesgoRochelle Ann CunananPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Tools Used in India Part-2Document6 pagesAssessment Tools Used in India Part-2Sumit ShahiPas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide To Finding Quality Child Care: You Have A Choice!Document12 pagesA Guide To Finding Quality Child Care: You Have A Choice!Adina GabrielaPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Psychology Worksheet Module 11Document7 pagesChild Psychology Worksheet Module 11Şterbeţ RuxandraPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Month Visit: Handout ParentDocument2 pages1 Month Visit: Handout ParentFauthPas encore d'évaluation

- CERTIFICATESDocument12 pagesCERTIFICATESRhoda Mae DelaCruz YpulongPas encore d'évaluation