Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Spirituality and Medicine Elective

Transféré par

NASCE_UFMGDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Spirituality and Medicine Elective

Transféré par

NASCE_UFMGDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Vol. 39, No.

313

Innovations in Family Medicine Education

Joshua Freeman, MD, Feature Editor Alison Dobbie, MD, Feature Editor

Editors Note: Send submissions to jfreeman3@kumc.edu. Articles should be between 5001,000 words and clearly and concisely present the goal of the program, the design of the intervention and evaluation plan, the description of the program as implemented, results of evaluation, and conclusion. Each submission should be accompanied by a 100-word abstract. Please limit tables or gures to one each. You can also contact me at Department of Family Medicine, KUMC, Room 1130A Delp, Mail Code 4010, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Kansas City, KS 66160. 913-588-1944. Fax: 913-588-2496.

A Spirituality and Medicine Elective for Senior Medical Students: 4 Years Experience, Evaluation, and Expansion to the Family Medicine Residency

Gowri Anandarajah, MD; Sister Maureen Mitchell, DMin

Background: Evidence suggests that spirituality is important in patient care and medical education, yet there are few reports of spirituality and medicine curricular evaluation. Methods: We developed, implemented, and evaluated a 17-hour elective on spirituality and patient care for 4 consecutive years. We presented the elective to 10 fourth-year medical students (MS4s) in years one and two and to eight MS4s and 15 residents, faculty, and staff in years three and four. We evaluated knowledge and skills using pre-course and post-course questionnaires and written cases and learner satisfaction using course evaluations. Results: Students knowledge improved on the evidence about spirituality, clinical resources, role of chaplains, approaches to patient care, and recognizing spiritual distress. Reported course strengths included diversity of topics and instructors, universal principles, small-group format, case discussions, and opportunity for self-reection. Comments reected enhanced value in the meaning in medicine and whole person care. Conclusions: Senior medical students rated the elective positively and increased their knowledge of spirituality and medicine. It was also positively received by residents, faculty, and staff and paved the way for residency curricula in this subject. (Fam Med 2007;39(5):313-5.) An emerging body of evidence demonstrates spiritualitys beneficial role in patient care.1-3 In response to that evidence, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC),4 the World Health Organization (WHO),5 and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations

From the Department of Family Medicine, Brown Medical School (Dr Anandarajah); and North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, NY (Sister Mitchell).

(JCAHO) all recommend including spirituality in clinical care and education. Currently, more than 50% of medical schools6 and 31% of family medicine residencies7 offer courses on spirituality and medicine. However, a 2006 MEDLINE search revealed few articles evaluating spirituality curricula.8-10 At Brown Medical School, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a 17hour elective designed to improve learners knowledge and skills regarding spirituality and patient

care. For 2 years, we presented this elective to fourth-year medical students (MS4s), and subsequently we opened it to residents, faculty, and staff. In this article, we describe our initial 4-year experience and report our evaluation data. Methods Curriculum Design and Development Brown Medical School is a private medical institution, in the northeastern United States, with

314

May 2007 of eight, 22 -hour sessions over 4 weeks (Table 1). After 2 years as an MS4 elective, we opened participation to family medicine residents, faculty, and staff. Evaluation We assessed changes in students knowledge and skills regarding spirituality and patient care using a pre-course and post-course Likert-style questionnaire with seven knowledge items, four skills items, and an opportunity for free text comments.12 We used a paired sample t test to demonstrate mean changes in before and after scores. We used a pre-course and postcourse case study, with questions requiring short, essay-style responses to assess students depth of understanding regarding spiritual

Family Medicine issues involved in the case. We measured learner satisfaction with the course using individual session evaluation forms (six item, ratings 15, with 5 highest), plus standard medical school course evaluation forms (nine item, ratings 16, with 6 highest, plus written comments) submitted by students directly to the Ofce of Student Affairs. We calculated means and ranges for all numerical ratings and performed qualitative analysis, using the immersion/crystallization method13 on students written comments. Results Student pre-course and postcourse questionnaires in year one (n=3) showed improvement in all knowledge and skills questions. Individual sessions averaged ratings

7587 students per year. Over 4 years, 18 MS4s completed this 17hour back to class elective (senior seminar), offered with other senior seminars during the nal month of fourth year. In year three, 15 family medicine residents, faculty, and staff also completed the elective. The course leaders, a family physician (Hindu) and a Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE)-trained hospice chaplain (Roman Catholic), selected core content based on a review of the literature,11 attendance at national conferences, and clinical experience. Guest speakers, carefully selected based on expertise, reputation, and proven clinical experience, included MDs, CPE chaplains, and PhDs from a variety of specialties, cultures, and faith backgrounds. The course consisted

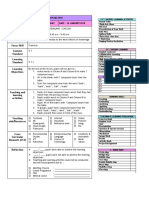

Table 1 Course Outline

Session 1 (2 hours) Topics 1. Introduction to the course/topic 2. Spirituality and Medicine From the Medical/Scientic Perspective Spirituality and the Care of the Patient: Culturally Sensitive Spiritual Assessment and Spiritual Care 1. The Role of the Physician 2. The Role of the Clinical Chaplain Spirituality and Medicine From the Perspectives of the Worlds Religions Part 1: Judaism Part 2: Christianity Spirituality and Medicine From the Perspectives of the Worlds Religions Part 3: Hinduism and Buddhism Part 4: Islam Part 5: Overall Discussion Self Understanding and Self Care: The rst step toward comprehensive, compassionate, whole-person care. Content Overview. Whole person care. Denitions of spirituality (secular and religious). Research and literature review. Clinical skills Training of clinical chaplains Resources Ethical/boundary issues Overview of basic tenets of each religion Implications for clinical care Same Teaching Method Lecture Discussion

Session 2 (2 hours)

Lecture, role-play Case discussions Optional shadowing experience Guest speakers Variety

Session 3 (2 hours)

Session 4 (2 hours)

Guest speakers Variety Discussion Story telling Careful facilitation by course leaders

Session 5 (2 hours)

Session 6 (2 hours)

Case Studies: Spirituality and the Pediatric Patient 1. Chronic Illness and Death of a Child 2. Birth of a Child Case Studies: Spirituality and Addiction Case Studies: Death and Dying/Hospice Course summary/evaluations

Themes, similarities, differences The telling of our own spiritual journeys Self-care strategies Biases/barriers to patient-centered care Skills for specic clinical scenarios

Session 7 (2 hours) Session 8 (2 hours)

Same Same Summary/feedback

Guest speakers Case-based discussions Stories Role-play Same Same Discussion, forms

Innovations in Family Medicine Education of 4.5 out of 5 (range 3.74.94), with the overall course averaging 5.96 out of 6. In year two (n=7), session ratings improved, with some changes in guest speakers and content. In year three, we successfully opened participation to the family medicine department. The participants (n=16) were an eclectic group of MS4s, residents, faculty (MDs, PhD, MSW, DMin, RD) and staff (RNs). After the eight scheduled sessions, the family medicine core group chose to incorporate monthly elective spirituality and medicine seminars into the residency curriculum, covering many additional topics. In year four, while the monthly family medicine residency series continued, the 1-month senior seminar was again offered to MS4s (n=7). Pre- and post-questionnaire matched pair analysis showed improvement in all seven knowledge and four skills questions. The greatest improvements were in knowledge of evidence (P=.042), resources for spiritual care (P=.006), the role of chaplains (P=.004), and skills in recognizing spiritual distress (P=.034). Qualitative analysis of pre- and post-course case write-ups revealed that after the course, students gave moredetailed answers, had more-dened approaches to understanding the patients spiritual concerns, and described a greater repertoire of resources to help in the patients care. Session evaluations averaged very good to excellent, with one outlier (new guest speaker). Overall course ratings averaged 5.5 out of 6 with relative weaknesses in amount of assigned readings (too little) and problem-based approach. Qualitative analysis of written feedback over all 4 years revealed the courses strengths as diversity of topics and instructors, universal principles of worlds religions, small-group format, case discussions, and opportunity for self-ref lection. Suggestions for improvement included more readings, additional topics, and eld trips. Overall comments stressed the value of meaning in medicine and whole-person care. Discussion Over these 4 years, our spirituality and medicine elective attracted small groups of enthusiastic participants who reported high satisfaction and demonstrated increased knowledge and skills. Presenting the elective was rewarding but labor intensive. However, this elective was successfully adapted to an optional monthly seminar series in the family medicine department for an additional 3 years and paved the way for an ongoing required curriculum in our residency program for the past 5 years. This elective was limited to a small number of participants at one medical school and residency program. While we successfully demonstrated improvements in students knowledge and skills, we did not demonstrate whether that improved knowledge translated into changed behavior in the clinical setting. As spirituality and medicine becomes more prominent in the medical literature, we recommend that some of this content be included in the required medical school and residency curricula to train a majority of learners, rather than a minority. Possible curricular venues include spiritual assessment and history during interview courses,9 clinical approaches in clerkships,8 or while teaching about death and dying. Additional content might include rounds with clinical chaplains; discussions of specic spiritual practices, for example, meditation and prayer; and beliefs specic to local and minority populations. Finally, content should reect a respect for the beliefs (and nonbeliefs), both secular and religious, of all learners and patients, thus lowering the barriers to providing high-quality, compassionate, whole-person care to our patients.

Vol. 39, No. 5

315

Acknowledgments: We thank Jeff Stumpff, MA, for assistance with quantitative analysis of precourse and post-course questionnaires, and Roger Mennillo, MD, and members of the Brown Family Medicine Department Scholarship Promotion Forum for reviewing the manuscript. Corresponding Author: Address correspondence to Dr Anandarajah, Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Department of Family Medicine, 111 Brewster Street, Pawtucket, RI 02860. 401-729-3272. Fax: 401-729-2923. gowri_ anandarajah@brown.edu. REFERENCES 1. Larimore WL, Parker M, Crowther M. Should clinicians incorporate positive spirituality into their practices? What does the evidence say? Ann Behav Med 2002;24(1):69-73. 2. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: implications for clinical practice. South Med J 2004;97:1194-1200. 3. Sulmasy DP. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. The Gerontologist 2002;42:24-33. 4. AAMC Report 1998: Report I of the Medical School Objectives Project. Learning objectives for medical school education: guidelines for medical schools. Acad Med 1999;74:461-2. 5. WHOQOL SRPB Group. A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Soc Sci Med 2006;62(6):1486-97. Epub 2005, September 13. 6. Fortin AH, Barnett KG. STUDENT JAMA. Medical school curricula in spirituality and medicine. JAMA 2004;291(23):2883. 7. King DE, Crisp J. Spirituality and health care education in family medicine residency programs. Fam Med 2005;37:399-403. 8. Musick DW, Cheever TR, Qinlivan S, Nora LM. Spirituality in medicine: a comparison of medical students attitudes and clinical performance. Acad Psychiatry 2003;27:6773. 9. King DE, Blue A, Mallin R, Thiedke C. Implementation and assessment of a spiritual history-taking curriculum in the rst year of medical school. Teach Learn Med 2004;16(1):64-8. 10. Barnett KG, Fortin AH VI. Spirituality and medicine: a workshop for medical students and residents. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(5):481-5. 11. Anandarajah G. Designing and implementing spirituality and medicine curricula for medical students and residents: getting started. Ann Behav Sci Med Educ 2002; 8(1):28-36. 12. Anandarajah G, Stumpff J. Attitudes, knowledge, and skills of clerkship medical students regarding spirituality and medicine. Ann Behav Sci Med Educ 2005;11(2):85-90. 13. Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications, Inc, 1999.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Views and Opinions of Teachers in A Brazilian Medical SchoolDocument5 pagesViews and Opinions of Teachers in A Brazilian Medical SchoolNASCE_UFMGPas encore d'évaluation

- Spirituality in UKDocument7 pagesSpirituality in UKNASCE_UFMGPas encore d'évaluation

- Spirituality in MedicineDocument7 pagesSpirituality in MedicineNASCE_UFMGPas encore d'évaluation

- Angústia Espiritual - RevisãoDocument11 pagesAngústia Espiritual - RevisãoNASCE_UFMGPas encore d'évaluation

- A Qualitative and Quantitative Study - Parnia and FenwickDocument8 pagesA Qualitative and Quantitative Study - Parnia and FenwickNASCE_UFMGPas encore d'évaluation

- Near Death Experiences - Pim Van LommelDocument7 pagesNear Death Experiences - Pim Van LommelNASCE_UFMGPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Smart GoalsDocument3 pagesSmart Goalsapi-266581680Pas encore d'évaluation

- Portfolio RubricDocument2 pagesPortfolio Rubricapi-245166476Pas encore d'évaluation

- Liberal Arts Mathematics - Teacher's GuideDocument400 pagesLiberal Arts Mathematics - Teacher's GuideMLSBU110% (1)

- Lesson 8: Higher Thinking Skills Through IT-Based ProjectsDocument17 pagesLesson 8: Higher Thinking Skills Through IT-Based Projectsharryleengitngitjune100% (7)

- Week: 3 Class / Subject Time Topic/Theme Focus Skill Content Standard Learning Standard Learning ObjectivesDocument9 pagesWeek: 3 Class / Subject Time Topic/Theme Focus Skill Content Standard Learning Standard Learning ObjectivesAlya FarhanaPas encore d'évaluation

- TPI Profile SheetDocument4 pagesTPI Profile SheeterickperdomoPas encore d'évaluation

- Advertisement No. 02/2015 ONGC Eastern Sector: ASSAM Application For ASSAMDocument1 pageAdvertisement No. 02/2015 ONGC Eastern Sector: ASSAM Application For ASSAMSaurav SenguptaPas encore d'évaluation

- KRA, Objectives, MOVsDocument31 pagesKRA, Objectives, MOVsQueenie Anne Soliano-Castro100% (1)

- CIW Student TextbookDocument390 pagesCIW Student Textbookcoollover100% (3)

- MEGIC Essential 1-3 PDFDocument8 pagesMEGIC Essential 1-3 PDFCristina Mendoza Ramon100% (1)

- Inclusive Innovation and Innovative ManagementDocument504 pagesInclusive Innovation and Innovative ManagementThan Nguyen100% (2)

- Classroom Activities For MusicDocument2 pagesClassroom Activities For Musicapi-237091625Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample SOP - Electrical EngineeringDocument1 pageSample SOP - Electrical EngineeringKishore ChandranPas encore d'évaluation

- Teacher Professional Growth Plan Peter Vooys 2 0Document5 pagesTeacher Professional Growth Plan Peter Vooys 2 0api-288533354Pas encore d'évaluation

- LPKPM SPM 2012 Bahasa Inggeris Paper 1 KDocument3 pagesLPKPM SPM 2012 Bahasa Inggeris Paper 1 KAndrew Chan100% (1)

- Math Module 3-Lesson 1Document12 pagesMath Module 3-Lesson 1Mabel Jason50% (4)

- Presentasi First Principles of Instructional by M David MerrilDocument20 pagesPresentasi First Principles of Instructional by M David MerrilRici YuroichiPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated Bibliography: Ideas For Public Libraries To Promote Lifelong LearningDocument13 pagesAnnotated Bibliography: Ideas For Public Libraries To Promote Lifelong Learningapi-199155734Pas encore d'évaluation

- CT20151665101 JLDocument3 pagesCT20151665101 JLAman KaushalPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Lesson Plan For Demo (Science 1)Document6 pages2022 Lesson Plan For Demo (Science 1)NOGARD FELISCOSOPas encore d'évaluation

- Individual Learner's Record (LR)Document1 pageIndividual Learner's Record (LR)JeTT LeonardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Done Virtual Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesDone Virtual Lesson Plan Templateapi-541728737Pas encore d'évaluation

- CURRICULUM VITAE - Docx - TO TRINH PDFDocument3 pagesCURRICULUM VITAE - Docx - TO TRINH PDFTrần Trí ThươngPas encore d'évaluation

- Belits Resume OnlineDocument2 pagesBelits Resume Onlineapi-550460644Pas encore d'évaluation

- Accommodations and ModificationsDocument1 pageAccommodations and Modificationsapi-549234739Pas encore d'évaluation

- For Newbs & Vets Exploration Guide RSD NationDocument8 pagesFor Newbs & Vets Exploration Guide RSD NationfloredaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading 4 B Memorias de Un Estudiante de Manila P JacintoDocument2 pagesReading 4 B Memorias de Un Estudiante de Manila P JacintoClaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maths Quest 11 Mathematical Methods CAS PrelimsDocument12 pagesMaths Quest 11 Mathematical Methods CAS Prelimspinkangel2868_14241150% (4)

- Designing Reading AssessmentDocument6 pagesDesigning Reading AssessmentRasyid AkhyarPas encore d'évaluation

- Booklist Y3: Pakistan International School Jeddah - English Section Academic Session 2020-2021Document1 pageBooklist Y3: Pakistan International School Jeddah - English Section Academic Session 2020-2021Fahad Nauman SafirPas encore d'évaluation