Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Assignment - Original

Transféré par

joshykottumkalDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Assignment - Original

Transféré par

joshykottumkalDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

INTRODUCTION The term social movement have commonly used in European languages in the early nineteenth century.

This was the period of social upheaval. The political leaders and authors who used the term were concerned with the emancipation of exploited classes and the creation of a new society by changing value systems as well as institutions and /or property relationships. However, since the early 1950s, various scholars have attempted to provide definitions of the concept of social movements. The works of Rudolf Heberle (1951, 1968), Herbert Blumer and Gustield are important. Rudolf Heberle gives the following definition of social movement: The main criteria of a social movement is that, it aims to bring about fundamental changes in the social order. Social movement is a collective attempt to reach visualized goal especially a change in certain social institutions. DISTINCTION BETWEEN SOCIAL AND POLITICAL MOVEMENT Political scientists and sociologists do not make a distinction between social and political movements. Sociologists assume that social movements also include those movements which have a clear objective of bringing about political change. Two volumes on social movements, edited by the sociologist M.S.A.Rao, include two such studies: the Naxalite movement which aims at capturing state power, and the backward caste movement for asserting a higher status. Rudolf Heberele argues that all movements have political implications even if their members do not strive for political power. Andre Gunder Frank and Marta Fuentes make a distinction between social and political movements. According to them, social movements do not strive for state power but it seek more autonomy rather than state power. There is a difference between social and political power, and the latter is located in the state alone. According to these authors, the objective of social movements is social transformation and the participants get mobilized for attaining social justice. When we analyze these authors arguments on the differences between social power and political power in the contemporary world is to gloss over reality, and to ignore the complexities of political processes. Politics is not

located only in the political parties. The authors ignore the political implications of the movements involving issues concerning the sense of justice and injustice. Any collective endeavour, we believe, to bring about social transformation change in the labour and property relationship and to struggle for justice and rights involves capturing or influencing political authority, though it may not be on the immediate agenda. Therefore, in the present context, the difference between social and political movements is merely semantic. Generally social movements can be classified as revolt, rebellion, reform, and revolution to bring about changes in the political system. Reform does not challenge the political system but, it attempts to bring about changes in the relations between the parts of th system in order to make it more efficient, responsive and workable. A revolt is a challenge to political authority, aimed at over-throwing the government. The recent Egyptian Movement is the best example for it. A rebellion is an attack on existing authority without any intention of seizing state power. In a revolution, a section or sections of society launch an organized struggle to overthrow not only the established government and regime but also the socio-economic structure which sustains it, and replace the structure by an alternative social order. In the course of political movements, various tribes develop stronger ethnic identities. Various tribes of Nagaland or Mizoram have built up an alliance for achieving political demands. Not only that, the tribals of Chota Nagpur have also begun to unite with the non-tribal toiling masses to fight against exploiters. They raise mainly economic and political demands. HISTORY OF JHARKHAND MOVEMENT The word Jharkhand, meaning "forest region," applies to a forested mountainous plateau region in eastern India, south of the Indo-Gangetic Plain and west of the Ganga's delta in Bangladesh. The term dates at least to the sixteenth century. In the more extensive claims of the movement, Jharkhand comprises seven districts in Bihar, three in West Bengal, four in Orissa, and two in Madhya Pradesh. Ninety percent of the Scheduled Tribes in Jharkhand live in the Bihar districts. The tribal peoples, who are from two groups, the Chotanagpurs and the Santals, have been the main agitators for the movement. Jharkhand is mountainous and heavily forested and, therefore, easy to defend. As a result, it was traditionally autonomous from the central government until the seventeenth century when its riches attracted the Mughal rulers. Mughal

administration eventually led to more outside interference and a change from the traditional collective system of land ownership to one of private landholders. These trends intensified under British colonial rule, leading to more land being transferred to the local tribes' creditors and the development of a system of "bonded labor," which meant permanent and often hereditary debt slavery to one employer. Unable to make effective use of the British court system, tribal peoples resorted to rebellion starting in the late eighteenth century. In response, the British government passed a number of laws in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to restrict alienation of tribal lands and to protect the interests of tribal cultivators. The advent of Christian missions in the region in 1845 led to major cultural changes, which were later to be important in the Jharkhand movement. A significant proportion of the tribes converted to Christianity, and schools were founded for both sexes, including higher institutions to train tribal people as teachers. Jharkhand's mineral wealth also has been a problem for the tribes. The region is India's primary source of coal and iron. Bauxite, copper, limestone, asbestos, and graphite also are found there. Coal mining began in 1856, and the Tata Iron and Steel Factory was established in Jamshedpur in 1907. The modern Jharkhand movement dates to the early part of the twentieth century; activity was initially among Christian tribal students but later also among nonChristians and even some non-tribals. Rivalries developed among the various Protestant churches and with the Roman Catholic Church, but most of the groups coalesced in the electoral arena and achieved some successes on the local level in the 1930s. The movement at this period was directed more at Indian dikus (outsiders) than at the British. Jharkhand spokesmen made representations to British constitutional commissions requesting a separate state and redress of grievances, but without much success. Independence in 1947 brought emphasis on planned industrialization centering on heavy industries, including a large expansion of mining. A measure of the economic importance of the Jharkhand mines is that the region produces more than 75 percent of the revenue of Bihar, a large state. The socialist pattern of development pursued by the central government led to forced sales of tribal lands to the government, with the usual problem of perceived inadequate compensation. On the other hand, government authorities felt that because the soils of the region are poor, industrialization was particularly necessary for the local people, not just

for the national good. However, industrial development brought about further influx of outsiders, and local people considered that they were not being hired in sufficient numbers. The nationalization of the mines in 1971 allegedly was followed by the firing of almost 50,000 miners from Jharkhand and their replacement by outsiders. Land was also acquired by the government for building dams and their reservoirs. However, some observers thought that very little of the electricity and water produced by the dams was going to the region. In addition, government forestry favored the replacement of species of trees that had multiple uses to the forest dwellers with others useful only for commercial sales. Traditional shifting cultivation and forest grazing were restricted, and the local people felt that the prices paid by the government for forest products they gathered for sale were too low. In the decades since independence, these problems have persisted and intensified. On the political front, in 1949 the Jharkhand Party, under the leadership of Jaipal Singh, swept the tribal districts in the first general elections. When the States Reorganisation Commission was formed, a memorandum was submitted to it asking for an extensive region to be established as Jharkhand, which would have exceeded West Bengal in area and Orissa in population. The commission rejected the idea of a Jharkhand state, however, on the grounds that it lacked a common language. In the 1950s, the Jharkhand Party continued as the largest opposition party in the Bihar legislative assembly, but it gradually declined in strength. The worst blow came in 1963 when Jaipal Singh merged the party into the Congress without consulting the membership. In the wake of this move, several splinter Jharkhand parties were formed, with varying degrees of electoral success. These parties were largely divided along tribal lines, which the movement previously had not seen. GENESIS OF JHARKHAND MOVEMENT This may be divided into three parts (a) Bloody revolts of the tribals (b) Moderate socio-economic movements (c) the political movements. (a) The bloody revolts: The period of bloody revolts of the adivasees to protect their Jharkhand land took place from 1771 to 1900 AD. The first ever revolt against the landlords and the British government was led by Tilka Manjhi, a valiant Santhal leader in Santal tribal belt in 1771. He wanted to liberate his people from the clutches of the unscrupulous landlords and restore the lands of their ancestors.

The British government sent its troops and crushed the uprisings of Tilka Manjhi. Soon after in 1779, the Bhumij tribes rose in arms against the British rule in Manbhum, now in West Bengal. This was followed by the Chero tribes unrest in Palamau. They revolted against the British Rule in 1800 AD. Hardly seven years later in 1807, the Oraons in Barway murdered their big landlord of Srinagar west of Gumla. Soon the uprisings spread around Gumla. The tribal uprisings spread eastward to neighbouring Tamar areas of the Munda tribes. They too rose in revolt in 1811 and 1813. The Hos in Singhbhum were growing restless and came out in open revolt in 1820 and fought against the landlords and the British troops for two years. This is called the Larka Kol Risings 1820-1821. Then came the great Kol Risings of 1832. This was the first biggest tribal revolt that greatly upset the British administration in Jharkhand. It was caused by an attempt of the Zamindars to oust the tribal peasants from their hereditary possessions. The Santhal insurrection broke out in 1855 under the leadership of two brothers Sidhu and Kanhu. They fought bitterly against the British troops but finally they too were crashed down. Then Birsa Munda revolt broke out in 1895 and lasted till 1900. The revolt though mainly concentrated in the Munda belt of Khunti, Tamar, Sarwada and Bandgaon, pulled its supporters from Oraon belt of Lohardaga, Sisai and even Barway. It was the longest and the greatest tribal revolt in Jharkhand. It was also the last bloody tribal revolt in Jharkhand. (b) Moderate movements of 20th century: The 20th century Jharkhand movement may be seen as moderate movement as compared to the bloody revolts of the 19 th century. Having the Chhotanagpur Tenancy Act 1908 to protect their lands, the tribal leaders now turned to socio-economic development of the people. In 1914 Jatra Oraon started what is called the Tana Movement. Later this movement joined the Satyagrah Movement of Mahatma Gandhi in 1920 and stopped giving land tax to the Government. In 1915 the Chotanagpur Unnati Samaj was started for the socio-economic development of the tribals. This organisation had also political objectives in mind. When the Simon Commission in 1928 came to Patna the Chotanagpur Unnati Samaj sent its delegation and placed its demand for a separate Jharkhand State for self-rule by the tribals. The Simon Commission however did not accede to the demand for a separate Jharkhand State. Thereafter Theble Oraon organised Kishan Sabha in 1931. In 1935 the Chotanagpur Unnati Samaj and the Kishan Sabha were merged with a view to acquire political power subsequently. (c) Jharkhand Party: Political Movement: In 1939 Jaipal Singh was invited to come to Ranchi from Darjeeling to join Adivasi Mahasabha. He came and joined the Adivasee Mahasabha and was elected its President. After the independence of

the country, the Adivasee Mahasabha was given the name of Jharkhand Party. Jaipal Singh remained the President of the Jharkhand Party from 1939 to 1960. The Jharkhand Party grew stronger politically gradually but various Commissions examining the demands for a separate Jharkhand State rejected its demand one after another. In August 1947 the Thakkar Commission rejected it saying that it would not be to the advantage of the adivasees. In 1948 Dar Commission also examined the demand for a separate Jharkhand state but rejected it on linguistic grounds. Despite these reports of these Commissions going negative in nature, Jharkhand Party never lost sight of its ultimate target a separate state of Jharkhand. It fought first General Election in 1952 and won 32 seats in the Bihar Assembly. In the second General Election in 1957 too Jharkhand Party won 32 seats and for two terms the party remained the leading opposition party. In 1955 the Report of the State Reorganisation Commission came out. Here too the demand for a separate Jharkhand state was rejected. In the third general election in 1962 the party could win only 23 seats in the Bihar Assembly. Personal interests of the Jharkhand leaders started playing upper hands. The party merged with the Congress Party in 1963. In the 4th General Election held in 1967 the party had a very poor show. It could win only 8 seats. The party was soon split into several splinter groups each claiming to be the genuine Jharkhand party. These were All India Jharkhand Party of Bagun Sumroi, Jharkhand Party of N.E. Horo, Hul Jharkhand Party of Justin Richard which further got fragmented and was called Bihar Progressive Hul Jharkhand Party led by Sibu Soren. Finally in 1973 Jharkhand Mukti Morcha was formed under the leadership of Sibu Soren. In 1986 All Jharkhand Students Union (AJSU) made its appearance on the political stage. In order to keep all these political parties in good humour, the Bihar Government brought out several Committees like Jharkhand Coordination Committee (JCC), a Committee on Jharkhand matters, Jharkhand Peoples Party (JPP) led by Dr. Ram Dayal Munda. All political parties carrying with themselves the name of Jharkhand gradually dwindled except the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha led by Sibu Soren. Creation of a new Jharkhand State In a historic move both the houses of Parliament passed the Bihar Reorganisation Bill 2000 during the first week of August and the President gave his assent to it a few days later. With this the stage is all set for the formal beginning of the governance of the new Jharkhand state from the 15 th of November 2000. This witnesses the fulfillment of the long cherished dream of the people of

Chhotanagpur and Santhal parganas for a separate state of Jharkhand. The new state will comprise of 18 districts in Santalparganas and Chotanagpur. These districts are: Ranchi, Gumla, Lohardaga, Singhbhum East, Singhbhum West, Palamau, Garhwa, Hazaribagh, Chatra, Koderma, Bokaro, Dhanbad, Giridih, Deoghar, Godda, Dumka, Pakur and Sahibganj. There will be 81 assembly seats, 14 Lok Sabha seats and 6 Raj Sabha seats in the new state.

Factors in the Jharkhand Movement DN Struggles against ethnic or national oppression are important for building democratic foundations for India. These struggles are also important for the working class. For all the segmentation of the labour market, there is nevertheless a connection among the segments. The Jharkhand movement thus deserves the support of all democrats and socialists. *\ THE resurgence of the Jharkhand movementhas raised a lot of hopes and fears. In the people of the area (tribals and nontribals alike) there is a renewed sense of unity and expectation, tinged with the apprehensive remembrance of past betrayals. In the ruling classes, both at the centre and the relevant states, there is concern at the possibility of new 'trouble spots', a concern increased by the significant presence of Marxist-Leninists in this latest phase of the Jharkhand movement. The States' Reorganisation Committee (SRC) in the mid-fifties had given a verdict against the formation of Jharkhand state on three grounds: the tribals are a minority in the region; there is no specific link language in Jharkhand; and the economic balance of the neighbouring states would be disturbed were Jharkhand state to be formed. The clinching reason must certainly have been the third, for the revenue and job-potential of the four states of Bihar, Orissa, Bengal and Madhya Pradesh would certainly be affected by the formation of Jharkhand state. Jharkhand forms a kind of reserve for the Indian economy as a whoie and for the economies of these four statesa. lot can be taken out and not much of it need be put back. Further, the expanding job opportunities in this mineral-rich area (the Ruhr of India) can be useful in mitigating the frustrations of youth in these four states. There is a common misconception that the Jharkhand demand is for an adivasi (or tribal) state. Then, it is very easily argued, as by the SRC, that since the adivasis do not form a majority of the population in this region, therefore the demand for

Jharkhand state, an adivasi state, cannot be granted. The adivasis (a term that originated in Jharkhand) are now less than 35 per cent of the population in this area. It is not certain when, if ever, they constituted a majority of the population. For the past few hundred years the adivasis of this area have lived in a symbiotic relation with various artisan and seivice castes, referred to as sadans, who now account for upto 50 percent of the population. In the many revolts in the area, the sadans too participated in large numbers. Though these sadans are often of the same castes as are found in the adjoining plains, yet there is little contact between the Jharkhand castes and their corresponding castes outside. Marriage, which is a very good indicator of the existence of social relations, is, even for these castes, confined to Jharkhandi circles.

COMPOSITE CULTURE The symbiotic relation between the adivasis and the sadans has resulted in the creation of a composite culture (and common psychological make-up). This composite culture of the Jharkhand, with its adivasi core, is somewhat different from the adjoining composite cultures of the plains. The sarna dharma, with its naturalistic base, has got fused with the religions that have come from the plains, whether Hinduism, Islam or Christianity. Adivasis and sadans alike partake of both sets of doctrines and practices. Song and dance (in theme, melody and rhythm) are more or less common to the various tribes and to the sadans. In fact, though the effect of both Hinduism and Christianity has been to look down upon communal dancing, the resurgence of the Jharkhand movement has influenced a return to communal dancing. Is there a material base for this shared Jharkhandi culture, a material base different from that of the plains? In the first place, the movement towards settled, plough agriculture is here much morerecent than it was in the plains. This movement is continuing even todaytribes like the Kharia only settled down in this century, while the Korwa (in Palamu) and many others are still settling down. Besides the regularly-cultivated lowlands, some amount of upland is also cultivated. The uplands, however, are not cultivatedregularly. A modified slash-and-burn agriculture is carried on in these uplandsthe land is cultivated every three or four years and jungle allowed to^ grow in between. Secondly, even where the adivasis have long ago taken to settled agriculture (as is the case with the Santhals, Mundas, Oraons and others) they nevertheless retain a considerable element of gathering (as

opposed to production) of forest produce in their economic life. Where deforestation has taken place migration for low-paid wage labour has replaced the collection and sale of forest produce, as a necessary supplement to the agriculturalincome. In areas where forests still exist forest produce yields at least half the income of a village. Further, the sadans, who (except for the traders like the Sahus and Telis or some of the former zamindari intermediaries) are generally worse off economically than the adivasis, depend even more than the latter on the collection and sale of forest produce. Consequently,the Jharkhand area as a whole is characterised by the combination of gathering and producing in its economic activities. A third factor in the shared Jharkhandi culture is the weakness of the process of endogenous state formation. The Chero and Nagbanshi kingdoms that did develop were more in the nature of pre-state formations, lacking as they did a standing army. K S Singh points out that this state formation too was a feature of the Dravidian tribes (Chero and Nagbanshi)where the land had been made into private property, and not of the Kolarian tribes (Santhal, Munda, Ho) where the land continued to remain the property of the clan. Among the Kolarian tribes there developed only dominant lineages and not a kingdom. The lack or weakness of endogenous state formation meant that the state machinery has remained alien to Jharkhandi society. When the British, for the first time, established an administrative machinery over the area, the intermediaries they had to use, whether traders, landlords, administrators or lowly-clerks and policemen, were largely from outsideleading to the identification of diku (meaning outsider) with exploiter. The weakness of endogenous state formation also meant that the armed people remained armeda condition reinforced by the continuing forest economy. This (the weakness of endogenous state formation) is not a factor of production. But it has certainly had its influence on the culture and psychological make-up of the Jharkhandis. NATIONAL QUESTION Conning back to the question of the nature of the demand for Jharkhand state, if it is not an adivasi state, then what is this Jharkhand state? The newly-formed Jharkhand Co-ordination Committee (JCC) has identified it as the demand of the Jharkhandi nationality. This immediatel raises from 'Marxists', as from the SRC, the objection that there is no common language in Jharkhand. This is true. It is also true that the existence of Economic and Political Weekly January 30, 1988 185 a common (or link) language would very much strengthen the process of nationality formation. But. does the absence of

a common language mean that a nationality cannot come into existence? Or, that until such a common language can be fashioned the people in question cannot claim the status of a nationality? The example of the Nagas, who even now have three major languagesthose of the Ao, Sema and Angami tribes shows that the absence of a common language need not prove an insuperable barrier. Nor, as Lenin had pointed out, did tiny Switzerland suffer because it had three official languages. Despite speaking French, Italian or German can anyone deny that the Swiss have evolved as a nation in their own right and not merely * as a multi-national state? And what about India itself? Is there an Indian nation coming into being, or are there only so many separate nationalities? In the name of Marxism there are many varieties of empiricism. Starting from definitions (in this case Stalin's definition of the nation) which are essentially ex post facto classificatory devices, they miss ouf on the historical processes involved. As a result unfolding history yields an increasing number of exceptions to the 'definition'. If we do not start from the fact that Lenin's and Stalin's analysis of the national question was situated in the problematic of Europe in the phase of capitalism, it will not be possible to comprehend the different processes in other parts of the world. For instance, in western Europe the strong, centralised state arose as a result of the formation and maturing of bourgeois nations. But in China, Egypt and, to an extent, India the" centralised state appeared in the feudal era itself. Marx had clearly realised that nations could arise under different conditions in different structures. Thus he refers to 'peasant nations' and 'pastoral nations'. These feudal and even pre-feudal nations are distinguished by Marx from 'hunting and fishing tribes'. The Chinese communists explicitly rejected the European

approach to the national question.-They used the word nationality to signify all ethnic groups, granting them all equal status, irrespective of the historical stage of development at which they were. The journey from tribe to lineage to nation is a long and complicated journey. In India the usual method, based on the material foundation of the spread of settled agriculture, has been the transformation of tribes into castes and then via the growth of local ruling (or sub-ruling) classes. Certain tribes, like the Ahoms of Assam and the Jats of Punjab, have themselves been central to the formation of the corresponding nationalities. More recently the Naga and Mizo tribes have evolved into distinct nationalities. Imperialism distorted the process of nation and nationality building by, among other things, setting up often arbitrary provincial boundaries. The tribes were the worst sufferers in this respect, divided up among various statesand they had no substantial exploiting classes which could weld them together in the fight for nationality status. Further, imperialism introduced wage labour and other cash relations. In these the Jharkhandis were accorded the position of 'drawers of water and hewers of wood'. Whether as providers of forest products or as suppliers of labour power they came at the bottom of the scalecoolie labour, first for the tea plantations, then for the coal mines and so on. This status of the Jharkhandis has not changed to this day. The absence of a recognised and mature national identity helps maintain this low status (low even within the working class

and other producing classes) of the Jharkhandis, Ethnic or national oppression/ discrimination add to and itensify class exploitation. National oppression deprives the workers of their dignity and weakens them in the fight against the extremes of exploitation to which they are subject. What imperialism and the Indian ruling classes want is that the Jharkhandis become a 'coolie nation', so that they can easily be suppressed as the lowest-paid workers and producers. This coolie status is evident not only among the expatriate Jharkhandis in the tea-gardens of Assam and Bengal (the earnings of these permanent workers is the lowest of all workers in large-scale enterprise, lower even than that of contract workers in many other industries) but also in the Jharkhandis' own homeland. CLASS EXPLOITATION The link between extreme class exploitation and national oppression was revealed in the mid-seventies wave of struggles in Dhanbad. The trade union struggle was correctly combined with that of identity assertionand it was this combination that brought some benefits to the lowest of the coal miners. For those who would be socialists and wish to think only in terms of benefits to the working class, that should be reason enough to support the movement for Jharkhand state. The ad vance of this movement, even without having achieved fulfilment in the creation of Jharkhand state, is already emboldening the Jharkhandi workersnot only those in Jharkhand but also those in

Bengal and Assam. The struggle for Jharkhand will not end class exploitation, but it will be a weapon in the hands of the most-deprived workers to end the extremes of exploitation and bring it (exploitation) to a more 'normal' level. Jharkhand will not automatically end this extreme exploitation, but it will decidedly be a weapon in that struggle. The extreme exploitation of the Jharkhandi workers is itself bound up with the depressed condition of the other major (rather, the major) class in Jharkhand, i e, Publishers of the Professional Social Sciences FOOD AND POVERTY India's Half Won Battle GILBERT ETIENNE There is nothing more important to drawing important policy conclusions from empirical evidence than the intuitive insights that come [from] many days of close association with the families whose efforts, hopes and aspirations are the stuff of good policyGilbert Etienne brings those intuitive insights from years of direct observation and experience. . . I can think of no more insightful observer of the Asian and particularly the Indian, rural scene.' John W Mellor, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D.C. After forty years of independence, India is free from the danger of devastating famines and is no longer at the mercy of grain imports. Yet, the battle is only half over,there remains the battle against poverty. It is this battle that Gilbert Etienne focuses on his absorbing study. 272 pages/225 x 145 mm/Rs 175 (hb)/Rs 85 (pb)/1988 S A G E PUBLICATIONS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED Post Box 4215. New Delhi 1.10048

186 Economic and Political Weekly January 30, 1988 the peasantry. As mentioned earlier, this peasantry is only in a few places a fullfledged peasantry, but otherwise combines gathering of forest produce with agriculture. The seth-mahajan-bureaucrat combine sucks the life blood out of these producers. Deforestation deprives them of their old world, and pushes them to the margin in the new world. The numerous dams and other projects have had much the same effect. In a particularly cruel irony, the number of dams in Jharkhand has been increasing, while the proportion of land irrigated in Jharkhand has been declining. Land has been closely associated with the political struggle in Jharkhand. The connection existed not only in the nineteenth century peasant uprisings, but has continued to the present day. The peasant uprising of 1969-70 in Debra-Gopiballavpur, spilling over into Baharagora and other adjoining areas of the Bengal-BiharOrissa border region, has become part of the folklore of Jharkhand. In the midseventies, outside Dhanbad, the spread of the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha was closely linked to militant mass movements for the recavery of land and other assets seized by the moneylenders. Forest issues have not got the same prominence fis land. But it should be remembered that the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act, enacted after the uprising led by Birsa Munda, recognised not ony the right to land but also, in some places, the community's right to the forests. These khuntkalti forests still remain under community and not government ownership. In

the mid-fifties Palamu witnessed a movement for 'jungle raj' led by the Kherwars, under Fetal Singh. In the seventies and eighties opposition to deforestation, monoculture of eucalyptus and the like have appeared on the agenda. Surprisingly the question of higher prices for forest produce has not got the attention it deserves. Why this has been so requires analysis. The problem of deforestation has merged into another problemthe typically modern one of displacement due to dams, mines, factories, cantonments and so on. The sudden loss of the conditions of labour (land and forest) has turned lakhs of Jharkhandis into destitutes, reduced to selling their labour power for a pittance. The demand for a state, for recognition as a nationality, is a demand within the limits of bourgeois democracy. It is a demand to end all forms of ethnic oppression and discrimination against the struggling nationality. It is a demand to be admitted as an equal partner in the building of the composite (multi-national) India. All of this places the demand for Jharkhand within the category of bourgeois democracy. GROWTH OF A PROTO-BOURGEOISIE But is there a bourgeoisie in Jharkhand? There are some who would deny the existence of a bourgeoisie in Jharkhand. They would even deny the existence of classes. But these are mere fictions. Not only are there different classes of producers among the Jharkhandis, there are also classes of exploiters among

the Jharkhandis. But they are not the main exploiters (who remain the imperialists, their compradors, the state and the big trader-moneylender-bureaucrat network). Whatever landlords and rich peasants exist are confined to the former ruling clans and dominant lineages. But community solidarity and common subordination somewhat modify the relationship of these classes with the labourers they employ. There is, for instance, the practice, not only in the tribes but also in the semi-tribal communities such as Mahatos, of master and servant eating together. The plates of both are washed by the women of the houseexpressing both the equality of men and the subordination of women. More important as exploiting classes are the growing sections of small traders and petty contractors. The former come mainly from the traditioinal, local trading castes, like Sahu and Teli; though there are new entrants from those like school teachers and other government employees, who do have some cash. These small traders are distinguished from the seths and mahajans not only by the small scale of their operations, but also by their relation with the sellers in buying operations. Jharkhandis distinguish two kinds of tradersthose who take the basket of goods in their hands before stating the price; and those who first settle the price and then take the basket. In the former case they recognise an element of force (the objectification of ethnic oppression). This is the practice of the seths and mahajans who turn ethnic oppression into profit.

Around the industrial centres and in connection with government works, some Jharkhandi petty contractors have grown up. Their origin lies mainly in attempts to buy off the Jharkhand movement at various times. Over the years one can identify the growth of a proto-bourgeois class of small traders and petty contractors. From just elements a decade ago, a class is now visible. Proto-bourgeois elements can be more easily bought off, than a proto-bourgeois class. The interests of this proto-bourgeois class definitely lie in the formation of a Jharkhand state, where they would be able to employ governmental and bureaucratic position to use the exchequer for their own accumulation. Significant entrants into the current phase of the Jharkhand movement are the educated youth. Here too the numbers have grown substantially. Both discrimination and the contempt in which the dominant nationalities hold them, have pushed the educated youth towards the Jharkhand movement. IMPORTANT FOR WORKING CLASS All in all, the conjunction of class and community interests in Jharkhand pushes in the direction of realising the ethnic, (nationality) aspirations. But whether this will in fact be achieved depends on the strength of the movement. If it pushes forward and links up with other democratic movements in the country, then the Jharkhandi identity could mature and strive to become an equal associate in the composite India. If it fails to push forward,

then the people of Jharkhand could continue along the present line and be turned into subordinate castes and coolie labour. Instead of concentrating on definitions, it is necessary to ask the question: Do the Jharkhandis face ethnic oppression? As the struggle against such oppression is obviously justified, the unity of the victims of this oppression and their common struggle can well lead to the formation of a nationality. Were the numerous Naga tribes already a nationality when they began to assert their right of selfdetermination in the 1950s? Or did they become a nationality in the course of this struggle? It is not for the high priests of the developed nationalities (or ^of the 'mainstream') to decide when ethnic groups that identify themselves as a commonality can be accorded the label of nation or nationality. Such matters will be decided on the field of struggle. When this process of struggle against national oppression is under way, it is the task of democrats to support it. Finally, this struggle is important not only for the Jharkhandis. Areas like Jharkhand are witness to a lack of bourgeois democracy, a lack even more severe than'that in the semi-feudal plains. More so than in the plains, armed suppression is the response of the state to movements in Jharkhand. Struggles against ethnic or national oppression and discrimination are important to build democratic foundations for India. These struggles are also important for the working class. The struggle to end discrimination and to raise the wages of the worst-off workers are necessary parts of the working class movement.

For all the segmentation of the labour market, there is nevertheless a connection between the segmentslow wages in the bottom segment help to depress the wage standard as a whole. The Jharkhand movement thus deserves the support of all democrats and socialists. Economic and Political Weekly January 30, 1988 187

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

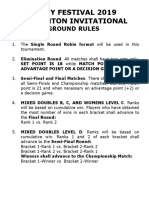

- Ground Rules 2019Document3 pagesGround Rules 2019Jeremiah Miko LepasanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Acfrogb0i3jalza4d2cm33ab0kjvfqevdmmcia - Kifkmf7zqew8tpk3ef Iav8r9j0ys0ekwrl4a8k7yqd0pqdr9qk1cpmjq Xx5x6kxzc8uq9it Zno Fwdrmyo98jelpvjb-9ahfdekf3cqptDocument1 pageAcfrogb0i3jalza4d2cm33ab0kjvfqevdmmcia - Kifkmf7zqew8tpk3ef Iav8r9j0ys0ekwrl4a8k7yqd0pqdr9qk1cpmjq Xx5x6kxzc8uq9it Zno Fwdrmyo98jelpvjb-9ahfdekf3cqptbbPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Lodge LeadershipDocument216 pagesLodge LeadershipIoannis KanlisPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Multiple Linear RegressionDocument26 pagesMultiple Linear RegressionMarlene G Padigos100% (2)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Delaware Met CSAC Initial Meeting ReportDocument20 pagesDelaware Met CSAC Initial Meeting ReportKevinOhlandtPas encore d'évaluation

- D5 PROF. ED in Mastery Learning The DefinitionDocument12 pagesD5 PROF. ED in Mastery Learning The DefinitionMarrah TenorioPas encore d'évaluation

- Mirza HRM ProjectDocument44 pagesMirza HRM Projectsameer82786100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Chapter 019Document28 pagesChapter 019Esteban Tabares GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- 1027 12Document3 pages1027 12RuthAnayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Booklet - Frantic Assembly Beautiful BurnoutDocument10 pagesBooklet - Frantic Assembly Beautiful BurnoutMinnie'xoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Created By: Susan JonesDocument246 pagesCreated By: Susan JonesdanitzavgPas encore d'évaluation

- Traps - 2008 12 30Document15 pagesTraps - 2008 12 30smoothkat5Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Trigonometry Primer Problem Set Solns PDFDocument80 pagesTrigonometry Primer Problem Set Solns PDFderenz30Pas encore d'évaluation

- Operational Effectiveness + StrategyDocument7 pagesOperational Effectiveness + StrategyPaulo GarcezPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Critical Review For Cooperative LearningDocument3 pagesCritical Review For Cooperative LearninginaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Ivler vs. Republic, G.R. No. 172716Document23 pagesIvler vs. Republic, G.R. No. 172716Joey SalomonPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument6 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Leisure TimeDocument242 pagesLeisure TimeArdelean AndradaPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Unidad 12 (libro-PowerPoint)Document5 pagesUnidad 12 (libro-PowerPoint)Franklin Suarez.HPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Public Service Media in The Networked Society Ripe 2017 PDFDocument270 pagesPublic Service Media in The Networked Society Ripe 2017 PDFTriszt Tviszt KapitányPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Zimbabwe Mag Court Rules Commentary Si 11 of 2019Document6 pagesZimbabwe Mag Court Rules Commentary Si 11 of 2019Vusi BhebhePas encore d'évaluation

- Rosenberg Et Al - Through Interpreters' Eyes, Comparing Roles of Professional and Family InterpretersDocument7 pagesRosenberg Et Al - Through Interpreters' Eyes, Comparing Roles of Professional and Family InterpretersMaria AguilarPas encore d'évaluation

- WaiverDocument1 pageWaiverWilliam GrundyPas encore d'évaluation

- BGL01 - 05Document58 pagesBGL01 - 05udayagb9443Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan MP-2Document7 pagesLesson Plan MP-2VeereshGodiPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative LawDocument7 pagesAdministrative LawNyameka PekoPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Ui-Ux-By Harry Muksit - SDocument109 pagesUnderstanding Ui-Ux-By Harry Muksit - Sgodzalli44100% (1)

- Hero Cash Cash Lyrics - Google SearchDocument1 pageHero Cash Cash Lyrics - Google Searchalya mazeneePas encore d'évaluation

- Working Capital Management-FinalDocument70 pagesWorking Capital Management-FinalharmitkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grade 3Document4 pagesGrade 3Shai HusseinPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)