Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Working Paper On The Partnership Principle in The EU Cohesion Policy

Transféré par

European Citizen Action ServiceDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Working Paper On The Partnership Principle in The EU Cohesion Policy

Transféré par

European Citizen Action ServiceDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

WORKING PAPER ON THE APPLICATION OF THE PARTNERSHIP PRINCIPLE IN EU COHESION POLICY

This working paper is prepared as a basis for discussion at the Open Days forum of 7 October on partnership. It is the first stage in a project bringing together ECAS and three Regions-Lazio (Italy), Region du Centre (France) and Lower Saxony (Germany). However this document is the responsibility of ECAS alone and does not commit the partners. It should be seen as parallel to the separate case studies from the 3 regions which are also presented at the forum

I. INTRODUCTION This working paper on the application of the Partnership principle in EU cohesion policy is a basis for discussion at the civil society forum during the open days for regions and cities on 7 October 2009 in Brussels. This event is held this year as a partnership between ECAS and Region du Centre (France), Saxony Anhalt (Germany) and Lazio (Italy). This overview should be read alongside the specific case studies each region will present at the Open Days forum. The case studies are based on a questionnaire from ECAS. The forum and other events will provide more input allowing us to develop this working paper and complete our report by the end of November. Open days is also an opportunity for finding more participants, so that a critical mass of regions come together to exchange personnel and best practice on partnership. The collective efforts of different stakeholders are regarded by the European Union (EU) as central to the Lisbon strategy for growth and jobs. Partnership is one of the guiding principles promoted as fundamental to the implementation of European Cohesion policy where it is seen as enhancing legitimacy, greater coordination of funds1 Both in EU policy documents and the academic literature, it is pointed out that partnership takes very different forms and is applied in different context: A distinction is made between vertical partnership among the European Commission, member states and regions and horizontal partnership between public authorities and private stakeholders: social partners, universities and civil society more generally. Partnership according to the regulations setting up the cohesion funds applies to all stages of the elaboration of strategies, programming, implementation and evaluation of the funds. A distinction is made therefore between two forms of partnership which in the social fund regulation is made quite explicit: partnership as a governance mechanism (art. 5) and partnership in relation to projects (art. 3). Partnership can take on a wide range of forms, depending on the size and constitutional structure of the member states and be more or less institutional or more or less legally binding, sometimes bringing together leading actors from organisations, sometimes the organisation themselves. Capacity building and delivery mechanism can be located in public authorities (ministries or regions) or be devolved to special overarching structures or technical assistance mechanisms.

In this working paper, the main focus is on horizontal partnership. The reason for this is that research has tended to concentrate on vertical partnership. This is because partnership as a system of multi-level governance among public authorities is an attractive topic for research and is part of managing programmes more effectively to achieve strategic objectives in meeting the complex demands of cohesion policy. The emphasis is on government, rather than on governance with its strong implication that public authorities cannot achieve their objective alone, but have to work in concert with civil society. There is in practice considerable overlap between vertical and horizontal partnership, but the conclusions of different studies that the partnership principle progressed in the 2000 2006 are based primarily on more evidence of the former, and scattered evidence of the latter.2

European Commission, Partnership in the 2000 -2006 Programming Period, Analysis of the implementation of the partnership principle. Discussion paper of DG Regio, 2005 2 Ex-post evaluation of Cohesion policy programmes 2000-06 co-financed by ERDF working package 11 final report

II. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PARTNERSHIP PRINCIPLE IN EU COHESION POLICY TO INCLUDE CIVIL SOCIETY The salient feature of this development has been on the one hand to extend vertical partnership - from member states to regions or other competent authorities and on the other to introduce and extend horizontal partnership to the social partners, which remain the privileged partners3, to civil society more generally. From a European perspective, the partnership principle was first introduced in 1988 as one the four fundamental principles governing the structural funds. Since then, the principle has evolved significantly starting from a narrow definition, which only included the Commission and the member states, to a wider partnership. In the negotiations for the 2007-2113 structural funds, member states were at first reluctant but finally accepted at the instigation of the European Commission the European Parliament and a coalition of European NGOs to add the following broadening out of the partnership principle in article 11: (c) any other appropriate body representing civil society, environmental partners, non-governmental organisations, and bodies responsible for promoting equality between men and women.

The clear historical trend is therefore for the theory and practice of partnership to progress, as the quid pro quo of the increasing decentralisation and application of the subsidiarity principle to structural fund operations. The inclusion of civil society generally as a partner in EU Cohesion policy from 2007 appears to have had a positive effect, even though it is too early to judge actual results. The fund regulation in the previous period created some uncertainty by singling out environmental partners and bodies responsible for promoting equality between men and women as to which NGOs should be involved. Authorities in the new member states in particular were not certain about the extent to which they should adopt an inclusive approach. They are now under more of an obligation to include the broad span of interests which can make a contribution to the strategy and programmes. There is also some evidence that the broader horizontal partnership has led to more consideration of civil society and the scope and limits of its participation in Cohesion policy by national authorities. Since the broader definition of partnership could build on the experience of the previous round of structural funds (2000 2006), socio-economic actors could begin to feel less like critical outsiders and more like participants in the process (cf. case study by Lazio). A narrow application of the previous definition of horizontal partnership input to policy and the execution of projects requiring the coming together a wide range of stakeholders was problematic. There is no simple definition of a civil society which is impossible to categorise: The common features of this sector are independence from governments, political parties or commercial interests i.e. definition in terms of what it is not.

Partnership in cohesion policy: European social fund support to social partners in the 2007-2013 period

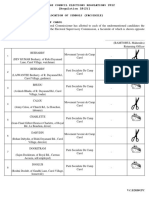

Unlike SMEs, (small and medium-sized enterprises) NGOs cannot be categorised according to size, since some are large organisations with important assets in land or property whilst others are run on a largely voluntary basis. There is a tendency to categorise NGOs in terms of advocacy (i.e. campaigning for authorities to provide services on introduce new laws in the public interest) or service delivery (i.e. providing assistance to their members or to a wider community with government support). Many organisations however cover both functions. There is no particular type of activity which does not have a civil society dimension, but as the box below suggests, NGOs are generally either concentrating on specific themes or on specific target groups in the population. The range of activity is so broad that nothing is typical, except that it tends to be replicated by government or the private sector.

Themes

Arts and culture Development and aid Environment Education and training Human rights and civil liberties Health Peace and conflict resolution Poverty and hunger Rural development Social enterprise/economic development Social rights and employment issues Wildlife and animal welfare Target groups Alcohol/drug addicts Children and youth Consumers Disabled Elderly Ethnic minorities Immigrants Refugees/asylum seekers Unemployed Women One of the problems for applying the partnership principle is the question what is civil society? to which there is no easy answer. Where answers are found, the definition and make-up of a particular civil society will shadow but is unlikely to correspond to the make-up of the public sector and the line ministries. The first step must be to overcome this barrier to understanding and dialogue. The advantage of the label civil society is that whilst it includes non-governmental organizations (NGOs), it is broader and can cover a wider range of interests and has in practice eroded the distinction 4

between stakeholder and citizen participation. Within the context of EU cohesion policies, there is often emphasis on definitions which stress the contribution NGOs make at the local level such as community development or their contribution to those parts of the economy which are more social than market. Thus for example in some countries, NGOs are seen as part of a broader social economy grouping associations, co-operatives, mutuals, and foundations. The notion of the Third Sector as distinct from the other two - the public and private sectors - denotes something similar. The label voluntary sector is also useful because it stresses the huge asset of NGOs in their ability to mobilize citizens and benefit from volunteers. All these labels are valid but none is entirely adequate for a sector which escapes easy categorisation. That is why the broad term civil society fits. The diffuse nature of civil society both raises unanswerable questions and tends to hide its real potential as a partner, since its real size and strength is invisible, undocumented and not even included in the national accounts: A study on global civil society in 40 countries conducted by the Johns Hopkins University has revealed that national and international quantitative and qualitative surveys of the sector tend to underestimate its real economic value, partly because it is not recognised as such in the national accounts and official statistics. This set of institutions is in fact a major economic and social force in virtually every country throughout the world (i.e. both industrialized and developing countries). In Europe, it represents about the same size as the construction industry and the financial services sector. Also, the Third Sector has been the most significant source of new jobs compared to other traditional sectors of the economy. From the same study, a similar picture emerged from data on expenditure. Overall, the Third Sector represents around 5% of the combined GDP in the countries studied. The comparative research carried out has also demonstrated that even in periods of recession the sector can grow and that it is the fastest creator of new jobs to meet new social needs in the services sector. In EU 27, 9-10% of the active population including volunteers are included in civil society. The origins and sources for considering partnership as a governance mechanism and as a tool for projects and are quite different: Partnership as a governance mechanism. The Commissions white paper on European governance of 2001 is still regarded by academics as the source for introducing the partnership principle in EU regional policy. In its guidelines for cohesion policy 2007-2013, the Commission shows itself to be a strong advocate for partnership which applies not only to the economic agenda but also to the broader effort to involve citizens who, through the partnership and multilevel governance arrangements under which cohesion policy is managed, can become directly involved in the Unions growth and jobs strategy The white paper resulted in the Commissions minimum standards of consultation of December 2002, which provides a useful guide, but applied only to Europeanlevel and not to decentralised policies. Further consideration of European governance was moved to the very different context of the Convention on the future of Europe, and in turn frozen by the negative French and Dutch referenda on the constitutional Treaty. Assuming the Lisbon Treaty is ratified, the governance debate is likely to be revisited in terms of article 11 and the principle of participatory democracy. Since the publication of the white paper, progress has also been made with plan D for democracy, dialogue and debate with experiments such as the citizens panels on the future of European rural policy OECD has also progressed the state of the art significantly, both 5

under the LEED forum on partnerships and local governance and its more general and comprehensive handbook for governments in information, consultation and participation. Partnership as a tool for projects In parallel, there has been a perceptible trend in EU policy making and projects to require broad partnerships round cross-cutting agendas for growth and jobs, sustainable development or migration. As the Commission puts it in the guidelines for cohesion policy: In this context, measures are important that seek to rehabilitate the physical environment, redevelop brownfield sites especially in old industrial areas, and preserve and develop the historical and cultural heritage with potential spin-offs for tourism development in order to create more attractive cities in which people want to live. The regeneration of existing public spaces and industrial sites can play an important role in avoiding suburbanization and urban sprawl, thereby helping to create the conditions necessary for sustainable economic development. More generally, by improving the planning, design and maintenance of public spaces, cities can plan out crime helping to create attractive streets, parks and open spaces which are safe and feel safe. In urban areas, the environmental, economic and social dimensions are strongly interlinked. A high quality urban environment contributes to the priority of the renewed Lisbon Strategy to make Europe a more attractive place to work, live and invest Such place-based approaches which can apply as much to rural as to urban developments require underpinning by a strong civil society. In parallel to the pull factors to develop the interface between public authorities and the citizen by introducing cross-cutting reforms in favour of more transparency, access and participation, there has been a corresponding push factor from the challenges cohesion policy has to face on the ground through more place-based, less sectoral, interventions. III. ADVANTAGES CLAIMED FOR PARTNERSHIP, BUT ALSO SOME OF THE OBSTACLES A key resource manual is the Guidebook how ESF managing authorities and intermediate bodies support partnership produced by the community of practice on partnership, which in turn grew out of the collaboration of a group of managing authorities in the EQUAL programme. The first part of the study analyses 10 reasons for partnership, which are summarised below, but also the obstacles faced. The second part called the key success factor framework starts with overarching pointers of good governance: accountability, participation and engagement, skills-building, appreciation of time. A detailed framework is then provided that shares a series of factors that have been successfully used in different Member States to promote partnership during each distinct phase of the programme cycle:

Operational Programme Analysis and Design carrying out a contextual analysis, promoting an enabling environment, identifying synergies with other programmes, and encouraging stakeholder engagement in the analysis and design process. Operation Programme Delivery Planning integrating stakeholders into programme procedures and setting up mechanisms for stakeholder involvement in projects Calls For and Appraisal Of Proposals supporting incorporation of partnership in project proposals and assessing partnership rationale and implementation mechanisms. Animation during Project Implementation providing ongoing support to partnership projects and building the capacity of stakeholders to actively participate in programme governance. Monitoring and Evaluation Reporting on the status of partnership projects, promoting participatory evaluation at both programme and project level, and systematically feeding back lessons about partnership into practice. At each stage of the cycle examples of practices that have worked successfully to endorse partnership in different Member States are given. A series of partnership in different Member States are given. A series of partnership pointers and tips from programme and project representatives, individual experts, NGO and social partner groupings are also provided. Advantages claimed for partnership The ten point rationale for partnership, extracted and summarised from the guidebook: 1. FOCUS We are able to more clearly identify gaps, needs and prioritiesand develop targeted approaches to address them. 2. COORDINATION Working in partnership can improve and synchronise policy coordination so that reach is improved and duplication avoided. 3. ACCESS TO RESOURCES A range of diverse resources from different stakeholders can be accessed in order to address particular problems and challenges. 4. SOCIAL CAPITAL Connections reinforce social networks while also promoting a deeper shared understanding 5. INNOVATION More creative approaches by sharing diverse perspectives, ideas and resources 7

6. CAPACITY BUIDLING Working in partnership with different actors can also enhance the opportunities for improving strategic and operative capacity 7. EMPOWERMENT Direct engagement with target groups should enable those who are disadvantaged/marginalised to have a stronger voice in the political arena 8. LEGITIMACY Wider stakeholder mobilisation can give a more democratic policy mandate as involvement and support of organisations that are trusted by society can increase public acceptance of necessary reforms 9. STABILITY The inclusion of civil society concernscan contribute to a more integrated and cohesive society. 10. SUSTAINABILITY Working in collaboration can promote long-term, durable and positive change

The obstacles to partnership The spread of good practice on partnership faces however obstacles which are often of a basic kind, before a partnership has even been bought into existence. When it has, as the ESF guidebook points out, working in partnership is not an easy option. Combining diverse organisational approaches resources and styles requires a considerable investment of time and energy Moreover, partnership has come under increased scrutiny to show that it makes an impact and that the sum is genuinely more important than the parts. This is not always easy to demonstrate Obstacles include: Information gaps to potential partners Whilst information on EU Cohesion policy has improved, stakeholders in either vertical or horizontal partnership do not always have a clear perception of the European policy context within which they are working. It helps if the European context is closely linked to the national development plan or regional policy. However, it is significant that a region like Lazio which is advanced in terms of the application of participatory democracy, feels that it is necessary to launch a new website on regional policy. Without better information and understanding, many actors whose participation is voluntary, do not make a link between their own activity and the policy and do not know where to start. Requirements for information and training are often too sophisticated and target those which are already insiders. The difficulty of adding horizontal to vertical partnership. The partnership between national and regional authorities and with the European Commission is in itself not an easy option, with many studies pointing to the distrust which can exist among different levels of governance. Adding on consultation and participation of stakeholders is seen as an additional burden. The latter often feel they are boarding the train late without a clear sense of its destination and the rules of engagement. Partnership can often create expectations which are not fulfilled, with NGOs finding that some of their arguments progress only to be rejected at the point of decision-making by powerful line ministries or regional authorities. The implication is that social partners, civil society and other stakeholders need to shadow the vertical partnership and also link up and operate at different geographical levels. Other difficulties in running a successful partnership. Although the difficulties could be encountered in almost any setting and in relation to any policy, there is still a sense that the most serious of these relate to the difficulties of managing a particularly demanding and complex policy, rather than resistance to partnership as such. Lack of time is the most frequently mentioned obstacle to creating partnerships. Such are the demands of management, reporting and the increasing frequency of checks and audits that it becomes increasingly difficult to add on partnership. This is even more the case, when all the advice goes in the direction of the need to invest in considerable prior preparation and on going efforts to nurture the partnership. Lack of capacity of the partners. Particularly in the new member states, authorities point to the lack of capacity of civil society organisations to engage with national and regional economic policy and their lack of resources to become active participants. Equally, whilst there are solutions to such problems, they require in turn time and effort to introduce facilities such as the use of technical assistance for capacity building or global grants. 9

Lack of stability. Despite the broad acceptance of partnership, it still meets with resistance from silo working by both public officials and NGOs or other civil society organisations. The case studies from the 3 regions also point out that there are inevitably different levels of engagement, with some partners more active than others and not necessarily sharing the same interests. In general, partnerships are a network of people, and so are not helped by frequent changes in personnel both in the administration and among stakeholders.

IV. ASSESSMENTS OF PARTNERSHIP WORKING IN PRACTICE The assessments are extremely difficult to make, except on the case-by-case basis shown by the three partner regions. This is made more complicated by the different national institutional arrangements for regional policy, which the ex-post evaluation report clarifies as follows: A regional government managed approach, as in Austria, Belgium, Germany (except for Objective 1 federal Ops) and Italy (Objective 2). States or provinces designed the programmes. Federal/national governments tended to be involved in the process late and to a limited extent, focusing on regulatory compliance issues and/or national funding issues. A regional approach, with national coordination or steering, as in Denmark, Finland, France, Italy (Objective 1), the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Regional authorities (provinces, regional councils, counties, devolved administrations) were responsible for the development of strategic priorities and drafting all or parts of programmes, but within a national framework or subject to national approval. A national government led approach, with regional input, as in Greece and Hungary. Programming consisted of a mix of programmes developed by national ministries based on standard national interventions (applied to each regional programme) and regionally defined elements. Programme drafts were shaped and approved by national inter-ministerial committees. Where Integrated Regional Operational Programmes were in place, regional authorities played a more active role (Poland). A national government managed approach, as in Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia and Slovenia. Programming was undertaken by government offices or interministerial groups, with regional/local and other bodies making inputs at various stages of the design process.

The different constitutional arrangements are not the only variable factor. There are also a number of different influences on partnership stemming from the particular decision-making process for the management of the funds. In some countries, i.e. new member states there is a close relationship between EU cohesion policy and domestic spending or the national plan. This may make mobilisation of a wide range of actors easier than in cases where the European funds are seen as a specialised addition to regional development. 10

In several countries, there are special instruments committees, working parties linking the different levels of government but it is not always apparent to what extent these are primarily coordination instruments, or also directed towards partnership. An example of the latter would be the National Thematic Group on Partnership in Sweden. In the evaluation report, the research for the European Parliament and the case study of Lower Saxony, there are examples of intermediate bodies to help develop capacity for the partnership. For example, in 1992 the Irish Government set up a company called Pobal which has responsibility for the national management, coordination and support of partnerships. It would make sense to review the achievements of such bodies and the regional development agencies which often play a similar role. Cross-cutting themes demand special or reformed partnerships. The ex-post evaluation of cohesion policy programmes contains an interesting chapter on sustainable development, which was subject to numerous different interpretations across member states and forms of partnership. Finally, there is a wide range of different consultation bodies. Some are formal forums also used for domestic economic and social policy, which gives them a certain weight and representativity (i.e. Austria). The disadvantage is that the actors in EU regional policy are to some extent specialised with their European links. In other cases, as in the UK, the practice appears to be more open invitations to respond to consultations on draft documents and public hearings. There could be a case for using both established mechanisms and more adhoc open systems.

Here is what the ex-post evaluation report says of enhanced partnership working over the period. Overall, there is evidence that partnership-working increased in the 2000-06 period. Among specific examples, Cohesion policy management in Ireland saw an increase in regional involvement following the creation of two new NUTS II regions. In Greece, a transition began to be made from top-down planning approach to more regional involvement with enhanced partnership working. In Spain and France, a system of co-responsibility between regional and central governments was introduced which allowed regions to take on more significant tasks and capacity in regional administrations. In the EU10, the introduction of partnership-working was sometimes difficult due to a lack of resources and experience (Latvia) and often remained at a rather formal level (Lithuania, Slovakia). However, some reported progress in collaborative working relationships during the course of the 2004-06 period, notably in Cyprus, where partnerships and public consultation schemes were strengthened and institutionalised. Lastly, in some Member States (Italy, Sweden, United Kingdom), it is clear that the experience of partnership within Cohesion policy programmes was being adopted within aspects of domestic regional development policy implementation.

11

One would have thought that comparisons would be easier by looking at monitoring committees the main vehicle for partnership, but reading between the lines of the evaluation report, this is apparently not the case. The extent of partnership in terms of both vertical and horizontal relationships differed considerably across the EU25 in the 2000-06 period. At the apex of the management structure, the Monitoring Committees provided the most important platform for formal partnership-working in all Member States. The composition of the Committee varied across countries, but typically included the Managing and Paying Authorities, regional and sectoral policy Ministries, regional authorities and development bodies, trades unions, employer organisations, chambers of commerce, NGOs (particularly in the gender equality and environmental fields), educational organisations, RTDI bodies and the voluntary sector. The Commission was also represented in an advisory (but often active) role. The regulatory requirements ensured wide partnership representation, an important factor in countries where this was weak in other areas of policymaking and where central and/or regional government authorities dominated the process. In Slovakia, for example, the EU requirements ensured that a third of the Monitoring Committee members were from central private sector and socio-economic partners. In Hungary, half of the Committee places were reserved for regional, economic, social and other partners, and in Lithuania, one third of the places were reserved for socioeconomic partners. Differences in practice are not explained only by the differences in constitutional settings or specific decision-making processes for EU Cohesion policy. Whilst there is probably more progression both towards regionalisation and towards partnership, there is also a natural tendency for research done for the EU Institutions, because it covers 27 member states, to gloss over the differences and difficulties, which are shown more in academic studies. Certainly, there is a difference between old and new member states. Old member states were shown to be able to build on the experience of previous financial perspectives and improve partnership. New member states were apparently not able to benefit enough from EU support prior to membership through Phare and pre-accession funds, so partnership was new. This difference will disappear over time and could be speeded up by more exchange of best practice. However, there are lessons here for future enlargements. Roughly, we can distinguish three categories: Regions/governments which pay lip service to the principle, giving purely formal and general accounts saying article 11 of the basic regulation has been implemented, but without saying how. Some authorities do not even appear to acknowledge that there is a specific requirement. However, most do. Not surprisingly, partnership tends to be viewed in this formalistic way particularly in new member states, where the emphasis is on compliance with the letter rather than the spirit of partnership and the overriding priorities are proper financial management and absorption of the funds. Those which go further and also describe a mixed picture, stressing both the advantages of partnership, but also some of its shortcomings, such as the lack of knowledge, organisation and commitment by the socio-economic partners and NGOs. Adding civil society to the regulation appears to have encouraged 12

more thinking about how to consult more widely. This is an interesting group, probably willing to learn more from best practice in more advanced regions. Those which go much further mostly the regions rather than the governments in developing wide-spread publicity and a well organised consultation plan. They also provide more details about what has been done: meetings, hearings, results and assessments of how partnership worked.

However, it has to be concluded that extracting any worthwhile or comparable information from the national strategic frameworks and the operational programmes is a daunting task.

13

V. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTED RECOMMENDATIONS The EU regulations make partnership an important part of the governance of cohesion policy, whilst leaving considerable latitude to national and regional authorities as to how it should be applied. This is evidently the right approach in a diverse community of 27 member states. It is currently however almost impossible to verify without a large research budget, if the partnership principle is applied correctly. This is one of the issues dealt with in the recommendations below. The application of the partnership principle faces a dilemma: On the one hand, since the partnership principle is the quid pro quo of subsidiarity, it would be paradoxical to attempt to force uniform application from the centre. There is also some evidence that partnership when seen as an imported European concept simply creates resistance, mistrust, a formalistic response, even though its application is fundamentally in the interests of the member states and regions themselves. On the other hand, civil society organizers and reformers in the public sector, where application of the partnership principle is weak, do look to the European Institutions and more advanced regions to offer guidance. Institutional differences can be exaggerated, particularly when it comes to horizontal partnership with non-state actors.

As the ESF guidebook points out: While country contexts undoubtedly differ, generic success factors for endorsing partnership have been identified and the lessons from these diverse experiences not only provide examples of how partnership can be promoted and reinforced in line with ESF regulations (as both a governance mechanism and in relation to projects), but also in finding solutions to address the challenges encountered in working collaboratively. Striking the right balance is not easy whilst the partnership principle has extended into a system of multilevel governance to include civil society, the Commissions communication on the 2000 2006 funds and the more extensive work package 11 in the export evaluation of cohesion policy programmes for the same period leave many questions unanswered. This is partly because of the different perspectives of new and old member states and the priority to absorbing enlargement. When it comes to evaluating the 2007 2013 funds these differences will have diminished to an extent, but this process should be speeded up as much as possible. Broad objectives should include initiatives to apply the partnership principle in a more balanced and consistent way across the funds. Based on the example of EQUAL, a programme to which partnership was central, guidelines have been mainstreamed in the European social fund through a community of practice. There has not been an equivalent development in regional policy, possibly because national and regional constitutional factors are a more dominant factor, but they are not such as to make creating a community of practice impossible. There should also be effort to give more attention not just to vertical partnership but to horizontal partnership also. For example, the study done for the European Parliament which was optimistic in its conclusions on the application of the partnership principle was based primarily on examining coordination and delivery mechanisms between member states and regions. Similarly, the European Commission could take the lead by targeting civil society more 14

deliberately when it consults on aspects of cohesion policy and its development after 2013. Whilst a centralizing approach to enforcement will not work, application of the partnership principle throughout all stages of the fund operations is nevertheless a legal requirement. The EU should therefore put the onus on a decentralized approach to enforcement, requiring member states and regions to apply the regulations and demonstrate that they have done so. Suggested recommendations: (i) The Commission should propose a new framework for multilevel governance and partnership

As the former Commissioner for regional policy, Danuta Hubner pointed out The European Union needs to rethink the concept of governance in order to better prepare its policies and implement them more efficiently and above all, in order to get closer to European citizens4. The entry to force of the Lisbon Treaty with its article 11 on the principle of participatory democracy will encourage such a process. The white paper on European governance of 2002 with its focus much more on stakeholder consultation than wider citizen participation now appears out of date. There are both new developments specific to partnership in the structural funds, and other initiatives such as the OECD handbook for governments on information, consultation and participation, which provide sufficient models for updating the message. (ii) The Commission should bring together local leaders in participatory democracy

One of the partners in this project Lazio is a region which has developed practices of participatory democracy involving both citizens and stakeholders on the basis of a specific regulation. The managing authority rightly points out: The risk that we constantly run into and that should be avoided entirely is to straight jacket the partnership exchange into a formal procedure, and especially to jeopardize the liveliness of the proactive contribution of all participants. This requires leadership and animation. The participatory democracy toolbox of citizens juries, consultations or town hall meetings is spreading. In Europe, there is still the challenge of marrying citizen and civil society consultation. Although such techniques are more associated with Porto Allegre and the U.S., some 90 citizens in Europe have introduced participatory budgeting. The spread of such techniques and their application to EU cohesion policy require above all political leadership. The Commission should identify and bring together the political leaders at national and local level who have made citizen participation a central feature of community building and strategy for the region. This could be lined to the recommendation in the ex-post evaluation report of the 2000 2006 period for a cohesion policy leadership programme.

Quoted y Jean-Marie Beauply, MEP on 30 October 2008

15

(iii)

Member states and regions should draw up an information, consultation and participation plan covering all stages of cohesion policy operators

All policy documents point in one way or another to the need for such a plan. The ESF Guidelines stress that partnership programmes and projects must devote adequate time and energy to developing an agreed vision. The DG regio discussion paper on partnership in the 2000 2006 programming period concludes that member states themselves could decide to organise a seminar at the start of the next programming period to discuss the envisaged partnership arrangements with the partners similarly the ex-post evaluation report concludes, particularly in relation to new member states, but this is equally valid for any region: The interpretation of partnership needs to be defined more clearly, specifying which organisations are regarded as partners, the expectations and aims of their contributions, and the ways in which they are to be involved at each stage of management and implementation. In this way, both sides understand the rules of the game which become more predictable. The implication of the ESF guidelines is that time and conflict with other priorities are the main obstacles to partnership. Investment of time in preparing the ground and having a plan before the partnership comes into being are therefore conditions for success. Without such a plan, accountability and evaluation are not possible. (iv) The plans should be published and outcomes evaluated

Even though there are reporting requirements for including sections on partnership in the strategic reference frameworks and operational programmes the results are incomplete and in no way comparable. This is not due to the diversity of structures across member states and regions, but to the fact that the extent of reporting on partnership is treated as optional. It is likely that participants in consultation exercises are also not receiving enough feedback and explanation of why some proposals were accepted and others rejected. This can be a main cause of frustration. Member states and regions should draw up and publish information, consultation and participation plans before the programming period. Reports on the results of the process should compare these to the actual outcomes (schedule of meetings, numbers of responses to requests for consultation and public information). In this way, it should be possible for citizens in one region to compare the results with other regions or across borders and to encourage the spread of the best practice which does exist. This should be part of a more dynamic and interactive approach with partners between more official events which in turn requires resources. (v) Capacity building of partners

The ex-post evaluation of the 2000-2006 programmes stresses that adequate capacities have to be available in partner organisations, and basic training on cohesion policy and the programme cycle is a necessary precondition for effective inclusion. Technical assistance at all geographical levels can be opened up for this purpose. A striking feature common to the selection of examples of best practice on partnership is the extent to which they originate in decisions to set up intermediate or supportive structures, providing a link between the public and private sphere for supporting the work of socio-economic actors and of the 16

managing authorities. Both Austria and Ireland for example have such special intermediate arrangements. Similarly, the case study of Saxony-Anhalt includes a competence centre for partnership which helps prepare social partners for meetings, carries out training and information activities and even prepared strategies. This is a successful example of supporting social and economic actors which could well be replicated. Such capacity building is necessary not only among civil society organisations but often for officials and regions which have insufficient experience in running information, consultation and participation exercises. (vi) Towards a community of practice on partnership in European regional policy

The implementation of the partnership principle should be a bottom-up exercise. Using technical assistance or the INTERREG programme, there is scope for a group of regions to establish a community of practice. This should include elected and appointed officials as well as socio-economic actors in civil society. Over time such a community of practice could produce for the regional fund the type of handbook or guidelines which exist for the social fund. The first step however would be to provide for an exchange and knowledge-building programme of study visit and one-to-one mentoring involving protagonists on both sides of the partnership equation. For example, region A is willing to learn more about the partnership capacity centre of region B whilst B wishes to learn about participatory budgeting in region C or the creation of a new website and interactive tools in region D. From such an exchange programme a network of contacts and one-stop shops could emerge and guidelines which could then become a model for mainstreaming the partnership principle.

17

MAIN SOURCES Partnership in the 2000 2006 programming period (discussion paper of DG Regio) (November 2005). Study done for the European Parliament: Governance and partnership in regional policy (PE. 397.245) (January 2008) Guidebook: How ESF managing authorities and intermediate bodies support partnership (December 2008). Ex-post evaluation of Cohesion policy programmes 2000 2006 Co-financed by ERDF working package 11 - Final report. European Policies Research Centre, Glasgow The illusion of inclusion access by NGOs to the structural funds in the new member states of Eastern and Central Europe, Brian Harvey, ECAS Available national strategic reference frameworks and operational programmes Partnership and Structural funds: from the principle to the reality social NGOs demands Discussion and case studies from the partner regions Lazio, Region du Centre and Saxony-Anhalt Policy network and institutional gaps in European Union structural funds management in Poland, Poznan University of economic (m.sapala@ae.poznan.pl; i.musialkowska@ae.poznan.pl ) Civil society participation in the structural and Cohesion policies in the Central European new member states (Kaman Dezseri, Institute for World Economy Budapest)

18

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Corporate Responsibility in Europe: Government Involvement in Sector-specific InitiativesD'EverandCorporate Responsibility in Europe: Government Involvement in Sector-specific InitiativesPas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons From Europe: A Comparative Seminar On Commissioning From The Third Sector in The EUDocument52 pagesLessons From Europe: A Comparative Seminar On Commissioning From The Third Sector in The EUNCVOPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Enterprise An International Literature Review 2006Document96 pagesSocial Enterprise An International Literature Review 2006Ray BrooksPas encore d'évaluation

- Cs Roadmap 2021 24 FinalDocument41 pagesCs Roadmap 2021 24 FinalAlecos KelemenisPas encore d'évaluation

- CFR PartngoDocument27 pagesCFR PartngoAbhishek YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Asymmetric Patterns in The Civil Society's Access To The European Commission. The Cases of DG FISMA and TRADEDocument31 pagesAsymmetric Patterns in The Civil Society's Access To The European Commission. The Cases of DG FISMA and TRADEgiuseppe.fabio.montalbanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fin - 16th Meeting of The Eastern PartnershipDocument7 pagesFin - 16th Meeting of The Eastern PartnershipEaP CSFPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaction Paper #6Document6 pagesReaction Paper #6Louelie Jean AlfornonPas encore d'évaluation

- GreenPaperonCitizenScience PDFDocument54 pagesGreenPaperonCitizenScience PDFdungenesPas encore d'évaluation

- Social EuDocument4 pagesSocial EuSimran LakhwaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Com 2013 280 Local Authorities in Partner Countries enDocument10 pagesCom 2013 280 Local Authorities in Partner Countries enAntónio TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Fes - Social Dialogue in Georgia - EngDocument31 pagesFes - Social Dialogue in Georgia - EngMarina MuskhelishviliPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyers-2002-European Journal of Political ResearchDocument28 pagesBeyers-2002-European Journal of Political ResearchRafaela PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparing NGO Influence in The EU and The U.S.: BriefDocument8 pagesComparing NGO Influence in The EU and The U.S.: BriefChristian RasmussenPas encore d'évaluation

- FN - Partnership Principle and PracticeDocument9 pagesFN - Partnership Principle and PracticeEuropean Citizen Action ServicePas encore d'évaluation

- Gaspp 92002Document107 pagesGaspp 92002Ibrahim ZahreddinePas encore d'évaluation

- Participation of Civil Society in EU Trade Policy Making How Inclusive Is InclusionDocument17 pagesParticipation of Civil Society in EU Trade Policy Making How Inclusive Is InclusionMAIMUN YUSUF YAHYEPas encore d'évaluation

- Hand Policy Recommendations-EnDocument7 pagesHand Policy Recommendations-EnRéka BaloghPas encore d'évaluation

- Art:10 1007/BF02929026 PDFDocument8 pagesArt:10 1007/BF02929026 PDFnisar.akPas encore d'évaluation

- Contextualising Public (E) Participation in The Governance of The European UnionDocument11 pagesContextualising Public (E) Participation in The Governance of The European UniongpnasdemsulselPas encore d'évaluation

- Communicating Europe': The Role of Organised Civil Society: Elizabeth MonaghanDocument14 pagesCommunicating Europe': The Role of Organised Civil Society: Elizabeth Monaghannesimtzitzii78Pas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing Eu Lobbying PDFDocument13 pagesAnalyzing Eu Lobbying PDFManojlovic VasoPas encore d'évaluation

- Analytical Paper - Successful Partnerships in Delivering Public Employment Services (2013)Document39 pagesAnalytical Paper - Successful Partnerships in Delivering Public Employment Services (2013)manosmatPas encore d'évaluation

- Code Good Practice of Civil ConsultationsDocument17 pagesCode Good Practice of Civil ConsultationsMadarász CsabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Socializing The European Semester: EU Social and Economic Policy Co-Ordination in Crisis and BeyondDocument27 pagesSocializing The European Semester: EU Social and Economic Policy Co-Ordination in Crisis and BeyondMillie Thorn von PropstPas encore d'évaluation

- Ultilevel Citizens New Social Risks and Regional Welfare: Working Paper Instituto de Políticas Y Bienes Públicos (Ipp)Document21 pagesUltilevel Citizens New Social Risks and Regional Welfare: Working Paper Instituto de Políticas Y Bienes Públicos (Ipp)Dimitri FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper No. 7Document24 pagesResearch Paper No. 7jairo cuenuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Theory of Partnership - Why Have Partnerships?Document39 pagesThe Theory of Partnership - Why Have Partnerships?Stuti SarafPas encore d'évaluation

- TerjemahanDocument6 pagesTerjemahanHukma ZulfinandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grammatikas - Administrative ConvergenceDocument23 pagesGrammatikas - Administrative ConvergenceVassilis GrammatikasPas encore d'évaluation

- Prof. Dr. Boban Stojanović, Jean Monnet ESSAYDocument5 pagesProf. Dr. Boban Stojanović, Jean Monnet ESSAYBoban StojanovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Position Paper v3 AugDocument61 pagesPosition Paper v3 AugGeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Management-Collaborative and Network-Based Forms of StrategyDocument19 pagesStrategic Management-Collaborative and Network-Based Forms of StrategyNoemi G.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Challenges For European Welfare Systems PDFDocument10 pagesChallenges For European Welfare Systems PDFar15t0tlePas encore d'évaluation

- Convocatoria Europea. European Union Programme For Employment and Social Solidarity ProgressDocument24 pagesConvocatoria Europea. European Union Programme For Employment and Social Solidarity ProgressGotzone MoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Dg-4-Afco Et (2003) 329438 enDocument68 pagesDg-4-Afco Et (2003) 329438 enEdited By MEPas encore d'évaluation

- Ocal Overnance and Artnerships: AS F Oecd S L PDocument14 pagesOcal Overnance and Artnerships: AS F Oecd S L PLenb AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 2a, 606-609Document26 pagesWeek 2a, 606-609Anika MullerPas encore d'évaluation

- Communication EUSA 2017Document13 pagesCommunication EUSA 2017Selia Faradisa MZPas encore d'évaluation

- Stubbs Zrinscak Social Policy and Croatia's EU MembershipDocument8 pagesStubbs Zrinscak Social Policy and Croatia's EU MembershipPaul StubbsPas encore d'évaluation

- Within and Without The State: Strengthening Civil Society in Conflict-Affected and Fragile SettingsDocument29 pagesWithin and Without The State: Strengthening Civil Society in Conflict-Affected and Fragile SettingsOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Theoretical Approaches of The Implementation System of European Cohesion PolicyDocument17 pagesTheoretical Approaches of The Implementation System of European Cohesion PolicyBourosu AlinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Greiss Et Al. - Europe As Agent That Fills The GapsDocument26 pagesGreiss Et Al. - Europe As Agent That Fills The Gapsjany janssenPas encore d'évaluation

- Bauhr Charron2020Document20 pagesBauhr Charron2020novaliePas encore d'évaluation

- Governance Vs Politics The European Union S Constitutive Democratic DeficitDocument20 pagesGovernance Vs Politics The European Union S Constitutive Democratic DeficitElenaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Stakeholders in Development of Social Economy Organizations in Poland: An Integrative ApproachDocument17 pagesThe Role of Stakeholders in Development of Social Economy Organizations in Poland: An Integrative Approachjanine mendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- p2p Public Services Finland 2012Document132 pagesp2p Public Services Finland 2012HD49Pas encore d'évaluation

- National CSR Policies enDocument46 pagesNational CSR Policies end_rusu_octavianPas encore d'évaluation

- Mazzeorinaldi 2016Document21 pagesMazzeorinaldi 2016JerardoMijailGomezOrosPas encore d'évaluation

- European Research Institute On Cooperative and Social EnterprisesDocument38 pagesEuropean Research Institute On Cooperative and Social EnterprisesRay CollinsPas encore d'évaluation

- NGO Participation in Policy Development FINALDocument27 pagesNGO Participation in Policy Development FINALdragan golubovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 10. The Public Policy Process Module 10. OutlineDocument13 pagesModule 10. The Public Policy Process Module 10. OutlineTanjim HasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Conceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and The United States Convergences and DivergenceDocument23 pagesConceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and The United States Convergences and DivergenceMuhammad AbdullahPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Community Sector Peak BodiesDocument5 pagesThe Role of Community Sector Peak BodiesJosé Silveira de PinhoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide To CSR in Europe - Country Insights by CSR Europes National Partner OrganisationsDocument157 pagesA Guide To CSR in Europe - Country Insights by CSR Europes National Partner OrganisationsLaksmana Indra ArdanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook On IntegrationDocument180 pagesHandbook On Integrationmuhammad_ajmal_25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Society Alliances and Coalitions Blog ENGDocument7 pagesCivil Society Alliances and Coalitions Blog ENGSaimir MustaPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief Austria On Moldovan Civil Society (2019)Document6 pagesBrief Austria On Moldovan Civil Society (2019)Mihai MihaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Integration - What WorksDocument84 pagesIntegration - What WorksMigrants OrganisePas encore d'évaluation

- NCERT Solutions Class 12 Political Science The End of BipolarityDocument13 pagesNCERT Solutions Class 12 Political Science The End of BipolarityRohan RonPas encore d'évaluation

- Jose Rizal and Ninoy AquinoDocument2 pagesJose Rizal and Ninoy AquinoLourdes EsperaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bendersky On Carl SchmittDocument15 pagesBendersky On Carl SchmittsdahmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Manuel Quezon's First Inaugural AddressDocument3 pagesManuel Quezon's First Inaugural AddressFrancis PasionPas encore d'évaluation

- 1byrne J J Mecca of Revolution Algeria Decolonization and TheDocument409 pages1byrne J J Mecca of Revolution Algeria Decolonization and Thegladio67Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mimi's Corner: Message From University Club President Amy KramerDocument4 pagesMimi's Corner: Message From University Club President Amy KramercolinPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakst Notes PDFDocument76 pagesPakst Notes PDFMahnoor AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Burma: United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Must Declare Burmese Junta's 2008 Constitution As NULL and VOIDDocument3 pagesBurma: United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Must Declare Burmese Junta's 2008 Constitution As NULL and VOIDBurma Democratic Concern (BDC)100% (2)

- Desert Exposure November 2013 PDFDocument56 pagesDesert Exposure November 2013 PDFdesertexposure100% (1)

- Which Voting System Is Best For Canada?: Stéphane Dion, MPDocument15 pagesWhich Voting System Is Best For Canada?: Stéphane Dion, MPGillian GracePas encore d'évaluation

- How To Read Žižek by Adam KotskoDocument15 pagesHow To Read Žižek by Adam KotskozizekPas encore d'évaluation

- CT-Sen Gotham Research Group For Chris Murphy (Oct. 2012)Document3 pagesCT-Sen Gotham Research Group For Chris Murphy (Oct. 2012)Daily Kos ElectionsPas encore d'évaluation

- MachiavelliDocument19 pagesMachiavelliLö Räine AñascoPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Blunder Land of Indian PoliticsDocument5 pagesIn The Blunder Land of Indian PoliticsVijay M. DeshpandePas encore d'évaluation

- Causes of Martial Law in PakistanDocument2 pagesCauses of Martial Law in Pakistangulled199365% (34)

- Altman y Pérez-Liñán, 2002, Sesión 8Document17 pagesAltman y Pérez-Liñán, 2002, Sesión 8nicolasibarra84Pas encore d'évaluation

- Associational Life in MyanmarDocument64 pagesAssociational Life in MyanmarAye Myint KyiPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti Defection Law in IndiaDocument5 pagesAnti Defection Law in IndiaAnonymous H1TW3YY51KPas encore d'évaluation

- Richards Final IPSD Paper PDFDocument31 pagesRichards Final IPSD Paper PDFSanjay MehrishiPas encore d'évaluation

- Camp CarolDocument3 pagesCamp CarolL'express MauricePas encore d'évaluation

- Conference Proceedings Crime Justice and Social Democracy An International ConferenceDocument406 pagesConference Proceedings Crime Justice and Social Democracy An International ConferenceAndrés AntillanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Municipal Republican Committee Reps 2012-2014Document21 pagesMunicipal Republican Committee Reps 2012-2014Mercer County GOPPas encore d'évaluation

- Georg Lukács Record of A Life An Autobiographical Sketch PDFDocument206 pagesGeorg Lukács Record of A Life An Autobiographical Sketch PDFPablo Hernan SamsaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. John Foot - Modern ItalyDocument285 pagesDr. John Foot - Modern ItalyTea SirotićPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethiopian Education Policy PDFDocument2 pagesEthiopian Education Policy PDFKristin83% (18)

- Lukács ReconsideredDocument250 pagesLukács Reconsideredphoibosapollo75Pas encore d'évaluation

- Roots of Yoruba Igbo ConflictDocument7 pagesRoots of Yoruba Igbo Conflictyemi akinade100% (1)

- Mandela's First Letter To VerwoerdDocument4 pagesMandela's First Letter To VerwoerdAustil MathebulaPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Theory of Impossibilism Chapter VII SPGB 1904 1921Document12 pagesPolitical Theory of Impossibilism Chapter VII SPGB 1904 1921Wirral SocialistsPas encore d'évaluation

- Mugabe Inside The Third ChimurengaDocument51 pagesMugabe Inside The Third ChimurengaRask Hetmański100% (4)