Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Phil Am Care Health Systems V CA

Transféré par

amazing_pinoyDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Phil Am Care Health Systems V CA

Transféré par

amazing_pinoyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Philamcare Health Systems v. Court of Appeals (2002) Ynares-Santiago, J.

Ratio decidendi: The insurable interest of respondents husband in obtaining the health care agreement was his own health. The health care agreement was in the nature of non-life insurance, which is primarily a contract of indemnity. Petitioner: Philamcare Health Systems, Inc. Respondents: Court of Appeals and Julita Trinos Facts Ernani Trinos applied for a health care coverage with Philamcare Health Systems. In the application form, he answered no to the question: Have you or any of your family members ever consulted or been treated for high blood pressure, heart trouble, diabetes, cancer, liver disease, asthma or peptic ulcer? The application was approved for one year and he was issued a Health Care Agreement. Trinos was entitled to avail of hospitalization benefits and out-patient benefits such as annual physical examinations and preventive health care. The agreement was extended for 2 years. The coverage was increased to P75,000.00 per disability. Ernani suffered a heart attack and was confined at the Manila Medical Center for one month. While her husband was in the hospital, Julita Trinos tried to claim benefits under the health care agreement. Philamcare denied her claim and said that the Health Care Agreement was void because of a concealment regarding Ernanis medical history. Doctors at the MMC discovered at the time of Ernanis confinement that he was hypertensive, diabetic and asthmatic. Trinos paid the hospitalization expenses of P76,000. After her husband was discharged from the MMC, he was attended by a physical therapist at home. Later, he was admitted at the Chinese General Hospital. One morning, Ernani had fever and died. On July 24, 1990, respondent instituted with the Regional Trial Court of Manila an action for damages against Philamcare Health Systems and its president, Dr. Benito Reverente. She asked for reimbursement of her expenses plus moral damages and attorneys fees. RTC: Judged in favor of Julita Trinos and ordered Philamcare Health Systems to pay and reimburse the medical and hospital coverage of the late Ernani Trinos worth P76,000 plus interest, moral damages of P10,000, P10,000.00 as exemplary damages, attorneys fees of P20,000.00, plus costs of suit. CA: Affirmed the decision of the trial court but deleted all awards for damages and absolved president Reverente. Petitioners arguments A health care agreement is not an insurance contract; hence the incontestability clause under the Insurance Code does not apply. The agreement grants living benefits, such as medical check-ups and hospitalization which a member may immediately enjoy so long as he is alive upon effectivity of the agreement until its expiration. Only medical and hospitalization benefits are given under the agreement without any indemnification. Petitioner argues that it is not an insurance company but a Health Maintenance Organization under the Department of Health. Issue: Is a health care agreement an insurance contract? Yes Ruling Section 2 (1) of the Insurance Code defines a contract of insurance as an agreement where one undertakes for a consideration to indemnify another against loss, damage or liability arising from an unknown or contingent event. An insurance contract exists where the following elements concur: (1) The insured has an insurable interest; (2) The insured is subject to a risk of loss by the happening of the designated peril; (3) The insurer assumes the risk; (4)

Such assumption of risk is part of a general scheme to distribute actual losses among a large group of persons bearing a similar risk; and (5) In consideration of the insurers promise, the insured pays a premium. Section 3 of the Insurance Code states that any contingent or unknown event, whether past or future, which may damnify a person having an insurable interest against him, may be insured against. Every person has an insurable interest in the life and health of himself. Section 10 provides: Every person has an insurable interest in the life and health: (1) of himself, of his spouse and of his children; (2) of any person on whom he depends wholly or in part for education or support, or in whom he has a pecuniary interest; (3) of any person under a legal obligation to him for the payment of money, respecting property or service, of which death or illness might delay or prevent the performance; and (4) of any person upon whose life any estate or interest vested in him depends. In the case at bar, the insurable interest of respondents husband in obtaining the health care agreement was his own health. The health care agreement was in the nature of non-life insurance, which is primarily a contract of indemnity. Once the member incurs hospital, medical or any other expense arising from sickness, injury or other stipulated contingent, the health care provider must pay for the same to the extent agreed upon under the contract. The answer assailed by petitioner was in response to the question relating to the medical history of the applicant. This largely depends on opinion rather than fact, especially coming from respondents husband who was not a medical doctor. Where matters of opinion or judgment are called for, answers made in good faith and without intent to deceive will not avoid a policy even though they are untrue. Thus, although false, a representation of the expectation, intention, belief, opinion, or judgment of the insured will not avoid the policy if there is no actual fraud in inducing the acceptance of the risk, or its acceptance at a lower rate of premium. In such case the insurer is not justified in relying upon such statement, but is obligated to make further inquiry. There is a clear distinction between such a case and one in which the insured is fraudulently and intentionally states to be true, as a matter of expectation or belief, that which he then knows, to be actually untrue, or the impossibility of which is shown by the facts within his knowledge, since in such case the intent to deceive the insurer is obvious and amounts to actual fraud. The fraudulent intent on the part of the insured must be established to warrant rescission of the insurance contract. Concealment as a defense for the health care provider or insurer to avoid liability is an affirmative defense and the duty to establish such defense by satisfactory and convincing evidence rests upon the provider or insurer. In any case, with or without the authority to investigate, petitioner is liable for claims made under the contract. Having assumed a responsibility under the agreement, petitioner is bound to answer the same to the extent agreed upon. In the end, the liability of the health care provider attaches once the member is hospitalized for the disease or injury covered by the agreement or whenever he avails of the covered benefits which he has prepaid. Under Section 27 of the Insurance Code, concealment entitles the injured party to rescind a contract of insurance. The right to rescind should be exercised previous to the commencement of an action on the contract. In this case, no rescission was made. The cancellation of health care agreements as in insurance policies require the concurrence of the following conditions: (1) Prior notice of cancellation to insured; (2) Notice must be based on the occurrence after effective date of the policy of one or more of the grounds mentioned; (3) Must be in writing, mailed or delivered to the insured at the address shown in the policy; (4) Must state the grounds relied upon provided in Section 64 of the Insurance Code and upon request of insured, to furnish facts on which cancellation is based. None of the above pre-conditions was fulfilled in this case. When the terms of insurance contract contain limitations on liability, courts should construe them in such a way as to preclude the insurer from non-compliance with his obligation. Being a contract of adhesion, the terms of an insurance contract are to be construed strictly against the party which prepared the contract the insurer. Ambiguity must be strictly interpreted against the insurer and liberally in favor of the insured, especially to avoid forfeiture. This is

equally applicable to Health Care Agreements. The phraseology used in medical or hospital service contracts must be liberally construed in favor of the subscriber, and should be strictly construed against the provider. Philamcare Health Systems Inc. had twelve months from the date of issuance of the Agreement to contest the membership of the patient if he had previous ailment of asthma, and six months from the issuance of the agreement if the patient was sick of diabetes or hypertension. The periods expired, so the defense of concealment or misrepresentation no longer lie. The health care agreement is in the nature of a contract of indemnity. Hence, payment should be made to the party who incurred the expenses. Respondent paid all hospital and medical expenses. She is entitled to reimbursement. Dispositive: The decision of the Court of Appeals is affirmed.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Law of War Part 4Document6 pagesLaw of War Part 4amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of War Part 2Document5 pagesLaw of War Part 2amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

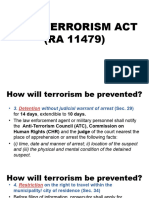

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 2Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 2amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of War Part 5Document3 pagesLaw of War Part 5amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of War Part 3Document3 pagesLaw of War Part 3amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of War Part 1Document3 pagesLaw of War Part 1amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 5Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 5amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- JR 2 RRDDocument3 pagesJR 2 RRDamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Military Justice System Part 2Document7 pagesMilitary Justice System Part 2amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Military Justice System Part 4Document5 pagesMilitary Justice System Part 4amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- NLRC Notice On PICOPDocument11 pagesNLRC Notice On PICOPamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 4Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 4amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 3Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 3amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Planner Cover PageDocument1 pagePlanner Cover Pageamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Military Justice System Part 3Document6 pagesMilitary Justice System Part 3amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Philippine Government Directory of Agencies and OfficialsDocument293 pages2022 Philippine Government Directory of Agencies and Officialsamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Annex B - AffidavitDocument1 pageAnnex B - Affidavitamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Language RoutineDocument1 pageLanguage Routineamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Blue Sands AttireDocument1 pageBlue Sands Attireamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines Map ChartDocument1 pagePhilippines Map Chartamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- INTERVIEW QUESTIONS (INCIDENT+IQ) - Ebanking Channels - FT, Bills Payment, Cardless WithdrawalDocument2 pagesINTERVIEW QUESTIONS (INCIDENT+IQ) - Ebanking Channels - FT, Bills Payment, Cardless Withdrawalamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Fully Booked Reading ChallengeDocument1 pageFully Booked Reading Challengeamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

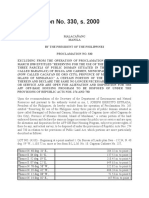

- PP 330Document2 pagesPP 330amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

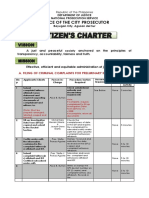

- OCP Bayugan CityDocument7 pagesOCP Bayugan Cityamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Every Good Boy Does FineDocument1 pageEvery Good Boy Does Fineamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

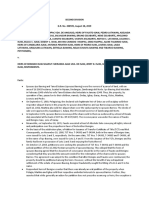

- Motion To Release Firearm SampleDocument2 pagesMotion To Release Firearm Sampleamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Self HelpDocument25 pagesSelf Helpamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ra 10121Document23 pagesRa 10121amazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- EstafaDocument241 pagesEstafaamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- JuneDocument21 pagesJuneamazing_pinoyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Rule 15 19 Case DigestDocument40 pagesRule 15 19 Case DigestAnonymous r1cRm7FPas encore d'évaluation

- Contracts Pointers 1Document16 pagesContracts Pointers 1Daniel Kristoffer Saclolo OcampoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sir Romar (Waiting For Revised Art. 13 and 14)Document8 pagesSir Romar (Waiting For Revised Art. 13 and 14)shahiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Stan Lee Lawsuit POWDocument20 pagesStan Lee Lawsuit POWgmaddausPas encore d'évaluation

- 41 Tul LRev 359Document23 pages41 Tul LRev 359manojvarrierPas encore d'évaluation

- ACE Foods, Inc. v. Micro Pacific Technologies Co., Ltd.Document3 pagesACE Foods, Inc. v. Micro Pacific Technologies Co., Ltd.viva_33100% (3)

- G.R. No. 222821, August 09, 2017 North Greenhills Association, Inc., Petitioner, V. Atty. Narciso MORALES, Respondent. Decision Mendoza, J.Document11 pagesG.R. No. 222821, August 09, 2017 North Greenhills Association, Inc., Petitioner, V. Atty. Narciso MORALES, Respondent. Decision Mendoza, J.Pearl LingbawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Escabarte vs. Heirs of IsawDocument2 pagesEscabarte vs. Heirs of IsawMicha Rodriguez100% (1)

- Carpio-Morales V Court of AppealsDocument8 pagesCarpio-Morales V Court of AppealsHarry Eugenio Jr AresPas encore d'évaluation

- Re Application For Admission To The Philippine Bar, Vicente D. Ching, 316Document2 pagesRe Application For Admission To The Philippine Bar, Vicente D. Ching, 316Red HalePas encore d'évaluation

- Motion For Rehearing (Final) r1Document46 pagesMotion For Rehearing (Final) r1jamcguirePas encore d'évaluation

- Complainant Vs Vs Respondent: First DivisionDocument9 pagesComplainant Vs Vs Respondent: First DivisionPaul Joshua Torda SubaPas encore d'évaluation

- Term Paper in Statutory ConstructionDocument17 pagesTerm Paper in Statutory ConstructionMichelle VillamoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Audit in CIS EnvironmentDocument5 pagesAudit in CIS EnvironmentKathlaine Mae ObaPas encore d'évaluation

- Code of Professional Conduct-ReviewerDocument4 pagesCode of Professional Conduct-ReviewerRabelais MedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ordonez v. USA - Document No. 3Document3 pagesOrdonez v. USA - Document No. 3Justia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases For Digest Criminal ProcedureDocument224 pagesCases For Digest Criminal ProcedureAR GameCenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Adekeye and Others VDocument1 pageAdekeye and Others VAbū Bakr Aṣ-ṢiddīqPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Negotiable Instruments, 6 Edition 2007: by Poh Chu Chai Lexis NexisDocument2 pagesLaw of Negotiable Instruments, 6 Edition 2007: by Poh Chu Chai Lexis NexisJohn Dx LapidPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhanani V Crasnianski (2011) Contract FormationDocument42 pagesDhanani V Crasnianski (2011) Contract FormationchrispittmanPas encore d'évaluation

- DELA CRUZ vs. ASIAN CONSUMER AND INDUSTRIAL FINANCE CORPORATIONDocument4 pagesDELA CRUZ vs. ASIAN CONSUMER AND INDUSTRIAL FINANCE CORPORATIONLou StellarPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases 1Document29 pagesCases 1Owen BuenaventuraPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.application ProceedingsDocument6 pages1.application Proceedingsliam mcphearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Lagrosas v. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Digest)Document2 pagesLagrosas v. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Digest)ArahbellsPas encore d'évaluation

- General Leasing and Managing AuthorityDocument14 pagesGeneral Leasing and Managing AuthorityKatharina SumantriPas encore d'évaluation

- Co OwnershipDocument7 pagesCo OwnershipYugenndraNaiduPas encore d'évaluation

- Case. Sarmiento vs. MisonDocument5 pagesCase. Sarmiento vs. MisonIrina MiQuiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mprevi 2002Document52 pagesMprevi 2002lamtran55100% (3)

- HRH Maharance of Borada V CompressDocument4 pagesHRH Maharance of Borada V CompressNavi AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Samsung 3127Document8 pagesSamsung 3127sabatino123Pas encore d'évaluation