Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

1 2

Transféré par

A.SkromnitskyDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1 2

Transféré par

A.SkromnitskyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Guest Editors Introduction

Frank Salomon, University of WisconsinMadison Sabine Hyland, St. Norbert College

Since about 2000, several converging debates have put Native American ways of writing (in the broadest sense: communicating by inscribed marks) onto the scholarly front burner. A sensible ethnohistorian might ask, whatever took so long? Isnt it evident that systems like pictography, petroglyphs, genealogical drawings, models of terrain, emblematic insignia, tribute tallies, colonial syllabograms, and the like form a very large part of humanitys graphic practice? Shouldnt anthropological common sense tell us that all kinds of inscription, not just true writing, make parts of a culture visible to its agents? Doesnt historical common sense decree that any account of a peoples past is incomplete if it fails to consider their way of organizing action through signs? Yet somehow, for a very long time, Amerindian graphic inventions, with the important exception of Maya writing, were hardly ever addressed in discussions about literacy. This neglect was not for lack of evidence. Readers of Ethnohistory hardly need to be reminded that 115 years have passed since Garrick Mallery published Picture-Writing of the American Indians (1893). Rather it was a result of conceptual discord about what writing is and which properties of graphismAndr Leroi-Gourhans (1993 [1964]: 187216) inclusivist termmerit study. In the first chapter of a deservedly influential compilation, The Worlds Writing Systems (1996), Peter T. Daniels reaffirmed a deep-rootedoriginally Aristoteliandefinition of writing as phonography: recording by means of signs that stand for segments of the speech stream. The attribute of interest was ability to unambiguously represent an utterance. Nobody can deny that scholars, including Mayanists, have

Ethnohistory 57:1 (Winter 2010) DOI 10.1215/00141801-2009-050 Copyright 2010 by American Society for Ethnohistory

Frank Salomon and Sabine Hyland

achieved legendary successes by following this formula. The unintended consequence, however, was to narrow grammatology down to studying civilization and phonetic writing, rather than the vast range of graphic behavior. An illogical but habitual corollary was that systems using other principles, or conveying information in ways other than verbal equivalence, were considered less worthy of study. These languished, defined only by what they were not: namely, not a part of the grand genealogy of letters as enshrined in the humanities. Discussions that return American inscriptions to the forefront are taking place in multiple arenas. Elizabeth Hill Boone and Walter Mignolos 1994 Writing without Words called this problem to the attention of a wide humanist audience, remobilizing Ignace Jay Gelbs 1952 attempt to theorize nonphonographic alternatives under the rubric of semasiography. By this Gelb meant signs that refer not to speech sounds but to the objects they name (music notation being a commonly cited example: written notes refer to sounds themselves, rather than to their verbal names). Semasiography seems at first to fit many American systems, such as clan insignia, at least at first glance. How far does this construct reach? The linguist Geoffrey Sampson (1985: 2645) has argued that general-purpose semasiography is an impossibility, because it would be impossibly prolific of signs. Semasiography appears to be a superior solution in cases where people lacking a common tongue must exchange information about a sharply delimited body of knowledge (as in music), and also in cases where the syntactic logic of sentences obscures a dissimilar logic in the thought to be communicated (as in mathematics). Many American scripts function under one or both of these conditions: for example, Panamanian shamanic pictography (Holmer and Wassn 1952, Severi 1997) or tributary and census khipu (Andean cord records). Semasiography is undergoing an immense, but questionably successful, growth as programmers strive for language-neutral ways to represent digital processes. The notion of semasiography also has defects. Mignolo (2003: 146) labels as problematic and obscure Giambattista Vicos declaration that all the nations have spoken in writing. Semasiography is a more precise term than Vicos notion of universal graphism was, but it too remains unanalytical. It uncomfortably throws together inscriptions whose systems of reference are similar but which differ in myriad other ways: systems of sign syntax, transient versus permanent signing, iconic or noniconic representation, standardizing versus esthetically innovating norms of inscription, and so on. Further theoretical sorting is needed. And when one actually digs into Amerindian graphic practice, one finds additional layers of complexity:

Introduction

many inscriptions use plural types of code. For example, Nahua pictography (Boone 2000) is often semasiographic but also in part phonographic and in part diagrammatica type of complexity likewise present in Maya and Egyptian systems. The long, quiet discussion about theorizing codes that are not writing proper has been taking place mostly in disciplinary interstices. Authors who offer rewarding attempts to parse not-exactly-writings into a more orderly space of study include philosophers writing about art (N. Goodman 1976 [1968]), semioticians writing about literacy (Harris 1995), art historians writing about symbolism (Elkins 1999), and linguists writing about the nonverbal (Benveniste 1985 [1969]). We do not yet have any consensual basis for sorting the cases or even agreement on what the analytical axes ought to be. The studies assembled here are primarily ethnographic, rather than theoretical. They demonstrate a wide enough range of cases to warn us that we should not be seeking any one, central New World graphic inclination but rather a fan of inventions exhibiting as much diversity as is already known from Old World studies. We do hope this collection will bring us from the ethnographic to the ethnological level of reading: we will see some common devices and usages and some axes of variation. We will gain an acute awareness that Amerindian inscriptions are as diverse as the social functions they had to address, but also be reassured that there is rhyme and reason in these functions relation to graphism. A second debate that returns Amerindian graphic usage to the limelight is taking place in the language-humanities groupings, chiefly English, Spanish, comparative literature, and the loose coalition called history of the book. Increasingly, literary scholars and literary historians see the colonial languages and their scripts as fields of interethnic contention rather than handmaidens of empire. Early (sixteenth-to-seventeenth-century) missionization took place in Christendoms most logocentric and catechetical moment, on both sides of the Reformation (Wandel 2006). Native American peoples quickly learned that inscription was the supremely authoritative form of language in the conquerors eyes. Everywhere in the New World this changed the terms of graphic practice. Interaction between native systems of pictography or emblematics and Christian scripture gave rise to many kinds of inscriptive readaptation. In this debate the colonial remaking of native graphism and the emergence of what one scholar (Cohen 2008) calls an alphabetic middle ground (echoing Whites 1991 coinage) become parts of a single fecund discussion. It was the theme of a conference at Duke University in 2008. However, for the most part, the discussion in language-humanities

Frank Salomon and Sabine Hyland

groupings (Gray and Fiering 2000) is reception discussion. It studies early perceptions of American languages and attempts at a philology of them, or concentrates on production of missionary texts, but has rarely included actual study of indigenous languages or inscriptions. Some parties to this discussion go as far as arguing that Amerindian discourse as rendered in Roman letters durably shaped New World literary directions (S 2004). Discussion about the Amerindian uptake of the alphabet suggests that when the original peoples took up the Roman alphabet, they used it innovatively, making it in effect a distinctive code. For the most part, literary humanists like Mignolo, often hewing to the discourse-and-power theses of Foucauldian theory, have emphasized the power of imperial literacy to suffocate, obscure, and even obliterate indigenous scripts. One can also imaginebut so far, only imaginea more positive study of the poetics that resulted from native peoples secondary graphogeneses (meaning cases in which the colonial situation stimulated new graphic inventions like the Algonquian and Yupik syllabaries). A third arena of study about Amerindian inscription is, of course, archaeology. The New Worlds greatest contribution to grammatology, the decipherment of Maya glyphsa true phonographic system, with other components adjoinedis no longer only a study of the classic Maya age. Archaeological finds such as the Cascajal block (Rodrguez Martnez et al. 2006) have begun to yield tantalizing evidence of Mesoamerican graphogenesis itself (Urcid Serrano 2001). In the Andean orbit, the discovery of khipus in a context that includes their mummified owners at Laguna de los Cndores (Urton 2001) and the study of khipus preserved within highland communities as patrimonial heritage (Salomon 2004) have enlivened discussion about khipus as the data infrastructure of polity. Although outside the scope of this volume, archaeological clarification of writing genesis (Houston 2004) promises to help ethnohistorians understand chronologically deeper strata to which our subject is related. Is there a New World answer to the perennial question about the relative importance of priestly and administrative functions in the emergence of scripts? Is the noun-plusnumber syntax typical of protocuneiform similar to khipu syntax? Does this comparison suggest that what was proto in relation to the Near East was further developed in the Andes in its protoness, tilting toward diagrammatic rather than verbal representation? Is the artfully redundant relation of icon to phonogram in Egypt an analogue to Mayan? Should we entertain the idea that phonography is not the only thing glyphs achieve? Because these potentials are not inherently bound to the pre-Hispanic ages, and can recur or interpenetrate in any age, archaeological teaching informs ethnography tellingly. The volume to result from a 2008 Dumbarton Oaks conference on

Introduction

Scripts, Signs, and Notational Systems in Pre-Columbian America will provide a powerful conspectus on the archaeological discussion. Close to archaeology, but never quite merged with it, runs a long conversation among specialists in textile technologies. Similar discussion occurs among students of other forms of inscription upon the human person such as paint and tattoo (chiefly in South America). Faced with bodies of emblems and canons about their display, such scholars have variously claimed to see semasiographies (Frame 2007, La Jara 1973, SilvermanProust 1988, Arnold 1997) or even logosyllabics (Ziolkowski, Arabas, and Szemiski 2008). Zorn (2004: 97105) has warned cogently that reading is all too easy a metaphor for the cognitive processing these signaries involve. A fourth arena of scholarship has long existed equally in history proper and among ethnohistorians trained in anthropology. This debate concerns the use of indigenous inscription in colonial-native interactions. Well-matured examples occur both in North America (e.g., William Fentons contributions on wampum in eastern Algonquian and Iroquois territories, 1998: 80, 92, 101, 125, 178) and to the south (e.g., Carlos Sempat Assadourians 2002 synthesis on khipu as colonial medium). Parallel discussions concern scripts and colonial mission frontiers north and south (e.g., Eskimo syllabaries, Algonquian hieroglyphs, the Sequoyah syllabary, and Andean catechetical pictography). Recent rounds of this deep-rooted literature concern the imperialist import of such interaction, most notably under the theme colonization of the imaginary. The latter phrase corresponds to the original French title of Serge Gruzinskis masterwork on Nahua and Spanish inscription in interaction (translated as The Conquest of Mexico 1993). It remains the fullest single treatment of transculturation and interpenetration between coexisting Amerindian and European scripts. Some authors see colonial graphogenesis such as the Sequoyah syllabary (Bender 2002) or northern plains winter counts and calendars (Greene and Thornton 2007) as transforming images in response to state or mission frontiers. That is, they are not analogues to European media, but reconceptualizations of own culture in the context of sudden, unequal entry into a transatlantic community of visual sign use. At the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Ethnohistory in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the double session Graphic Pluralism brought together a hemispheric sampling of researchers concerned with one kind of Amerindian literacy problem. That class consists of situations in which conquest and colonization brought together Amerindian and European ways with signs, sometimes generating durable coexistence.

Frank Salomon and Sabine Hyland

Some of the problems researchers see in the course of their new forays are relatively code-internal: they concern the grammars of individual codes themselves and mechanisms of interpenetration among them. Others involve what linguists call external history. They pertain to the agenda of understanding writing and writings as parts of social communication regimes. The latter sort of studies ask, for example, what are the information needs of varied social formations: clan, precapitalist state, colonial tribe, interethnic alliance, innovative sect? In given cases, how do inscriptive systems gain or lose constative or performative authority? Where is control of codes lodged? What roles do cultural privacy and vernacularity play on the one hand, or lingua franca expansion on the other? The 2007 session took place at the portal of two larger ventures. One is the quest for a more omnidirectional grammatology, suited for understanding the properties of inscriptions outside the canonical terrain of writing. The other is a media historiography that places the originality of New World graphism into the complexity of mixed-media situations evolving around the edges of the transatlantic empires. That applies both to political empires and to hidden variation in the seemingly more unitary empire of letters. What were the diversities of intercultural life when code itself was diverse? In many parts of the New World, during at least four centuries, graphic pluralism provided an extra dimension to cultural complexity. Two centuries elapsed between Columbuss landfall and early proposals for a republic of letters generating enlightenment through a single common public medium, the alphabet (D. Goodman 1996: 10). When todays indigenous groupsCherokee friends of the Sequoyah script, Maya hieroglyphic revivalists, or Inuit partisans of syllabographyaffirm continuing value in a graphic diversity that predated the republic of letters, they remind us that Indian writings are more central than ever to a larger ethnohistorical literacy. References

Arnold, Denise 1997 Making Man in Her Own Image: Gender, Text, and Textile in Qaqachaka. In Creating Context in Andean Cultures. Rosaleen HowardMalverde, ed. Pp. 99134. New York: Oxford University Press. Bender, Margaret Clelland 2002 Signs of Cherokee Culture: Sequoyahs Syllabary in Eastern Cherokee Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Benveniste, mile 1985 [1969] The Semiology of Language. In Semiotics: An Introductory Anthol-

Introduction

ogy. Robert E. Innis, ed. Pp. 22546. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Boone, Elizabeth Hill 2000 Stories in Red and Black: Pictorial Histories of the Aztecs and Mixtecs. Austin: University of Texas Press. Boone, Elizabeth Hill, and Walter D. Mignolo, eds. 1994 Writing without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Cohen, Matt 2008 Prospectus: Early American Mediascapes. Presentation at the conference Early American Mediascapes, Duke University, Durham, NC, 15 16 February. Daniels, Peter T. 1996 The Study of Writing Systems. In The Worlds Writing Systems. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, eds. Pp. 320. New York: Oxford University Press. Elkins, James 1999 The Domain of Images. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Fenton, William Nelson 1998 The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. Frame, Mary 2007 Lo que Guaman Poma nos muestra, pero no nos dice sobre Tukapu Revista Andina 44: 969. Gelb, Ignace Jay 1952 A Study of Writing: The Foundations of Grammatology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Goodman, Dena 1996 The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Goodman, Nelson 1976 [1968] Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. Gray, Edward G., and Norman Fiering. 2000 The Language Encounter in the Americas, 14921800: A Collection of Essays. New York: Berghahn Books. Greene, Candace S., and Russell Thornton, eds. 2007 The Year the Stars Fell: Lakota Winter Counts at the Smithsonian. Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, and University of Nebraska Press. Gruzinski, Serge. 1993 The Conquest of Mexico: The Incorporation of Indian Societies into the Western World, 16 th18 th Centuries. Cambridge: Polity Press. Harris, Roy 1995 Signs of Writing. London: Routledge. Holmer, Nils Magnus, and S. Henry Wassn 1952 The Complete Mu-Igala in Picture Writing: A Native Record of a Cuna

Frank Salomon and Sabine Hyland

Indian Medicine Song. Etnologiska Studier. Vol. 21. Gteborg: Gteborgs Etnografiska Museet. Houston, Steven 2004 The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. New York: Cambridge University Press. La Jara, Victoria de 1973 La dcouverte de lcriture pruvienne. ARCHEO (Lima) 62: 815. Leroi-Gourhan, Andr 1993 [1964] Gesture and Speech. Cambridge: MIT Press. Mallery, Garrick 1893 Picture-Writing of the American Indians. Annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Vol. 10 (188889) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Mignolo, Walter 2003 The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization. 2nd Ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Rodrguez Martnez, Mara del Carmen, Ponciano Ortz Ceballos, Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Stephen D. Houston, Karl A. Taube, and Alfredo Delgado Caldern 2006 Oldest Writing in the New World. Science 313 (5793): 161014. S, Lcia 2004 Rain Forest Literatures: Amazonian Texts and Latin American Culture. Cultural Studies of the Americas, no. 16. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. Salomon, Frank 2004 The Cord Keepers: Khipus and Cultural Life in a Peruvian Village. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Sampson, Geoffrey 1985 Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Sempat Assadourian, Carlos 2002 String Registries: Native Accounting and Memory according to the Colonial Sources. In Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu. Jeffrey Quilter and Gary Urton, eds. Pp. 11950. Austin: University of Texas Press. Severi, Carlos 1997 Kuna Picture-Writing: A Study in Iconography and Memory. In The Art of Being Kuna. Mari Lyn Salvador, ed. Pp. 24570. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. Silverman-Proust, Gail P. 1988 Weaving Technique and the Registration of Knowledge in the Cuzco Area of Peru. Journal of Latin American Lore 14, no. 2: 20741. Urcid Serrano, Javier 2001 Zapotec Hieroglyphic Writing. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. Urton, Gary 2001 A Calendrical and Demographic Tomb Text from Northern Peru. Latin American Antiquity 12, no. 2: 12747.

Introduction

Wandel, Lee Palmer 2006 Eucharist in the Reformation: Incarnation and Liturgy. New York: Cambridge University Press. White, Richard 1991 The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 16501815. New York: Cambridge University Press. Ziolkowski, Marius, Jarowslaw Arabas, and Jan Szemiski 2008 Tuqapu (tocapu): Una escritura logogrfica en el imperio inca? Paper presented at VII Congreso Internacional de Etnohistoria, Lima, 5 August. Zorn, Elayne 2004 Weaving a Future: Tourism, Cloth, and Culture on an Andean Island. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- IncaoccupationsaragurofinalDocument414 pagesIncaoccupationsaragurofinalA.SkromnitskyPas encore d'évaluation

- 1110176108Document36 pages1110176108A.SkromnitskyPas encore d'évaluation

- War and Early State Formation in The Northern Titicaca Basin, PeruDocument6 pagesWar and Early State Formation in The Northern Titicaca Basin, PeruA.SkromnitskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Spanish Use of Inca Textile Standards: Catherine J. JulienDocument25 pagesSpanish Use of Inca Textile Standards: Catherine J. JulienA.SkromnitskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Hunting Technologies in Andean Culture: Glynn CustredDocument14 pagesHunting Technologies in Andean Culture: Glynn CustredA.SkromnitskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Book of Games Alfonso X 1283Document65 pagesBook of Games Alfonso X 1283A.Skromnitsky100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 1.SDH Basics PDFDocument37 pages1.SDH Basics PDFsafder wahabPas encore d'évaluation

- Application of Geoelectric Method For GroundwaterDocument11 pagesApplication of Geoelectric Method For GroundwaterMunther DhahirPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Channels: A Strategic Tool of Growing Importance For The Next MillenniumDocument59 pagesMarketing Channels: A Strategic Tool of Growing Importance For The Next MillenniumAnonymous ibmeej9Pas encore d'évaluation

- ALE Manual For LaserScope Arc Lamp Power SupplyDocument34 pagesALE Manual For LaserScope Arc Lamp Power SupplyKen DizzeruPas encore d'évaluation

- 24 DPC-422 Maintenance ManualDocument26 pages24 DPC-422 Maintenance ManualalternativbluePas encore d'évaluation

- CiscoDocument6 pagesCiscoNatalia Kogan0% (2)

- Epreuve Anglais EG@2022Document12 pagesEpreuve Anglais EG@2022Tresor SokoudjouPas encore d'évaluation

- Predator U7135 ManualDocument36 pagesPredator U7135 Manualr17g100% (1)

- Trade MarkDocument2 pagesTrade MarkRohit ThoratPas encore d'évaluation

- Mahesh R Pujar: (Volume3, Issue2)Document6 pagesMahesh R Pujar: (Volume3, Issue2)Ignited MindsPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 To 20 Years - Girls Stature-For-Age and Weight-For-Age PercentilesDocument1 page2 To 20 Years - Girls Stature-For-Age and Weight-For-Age PercentilesRajalakshmi Vengadasamy0% (1)

- Importance of Communications 05sept2023Document14 pagesImportance of Communications 05sept2023Sajib BhattacharyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Artificial Intelligence Techniques For Encrypt Images Based On The Chaotic System Implemented On Field-Programmable Gate ArrayDocument10 pagesArtificial Intelligence Techniques For Encrypt Images Based On The Chaotic System Implemented On Field-Programmable Gate ArrayIAES IJAIPas encore d'évaluation

- DFo 2 1Document15 pagesDFo 2 1Donna HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

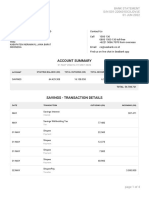

- Seabank Statement 20220726Document4 pagesSeabank Statement 20220726Alesa WahabappPas encore d'évaluation

- TFGDocument46 pagesTFGAlex Gigena50% (2)

- Arduino Uno CNC ShieldDocument11 pagesArduino Uno CNC ShieldMărian IoanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4 - Basic ProbabilityDocument37 pagesChapter 4 - Basic Probabilitynadya shafirahPas encore d'évaluation

- BJAS - Volume 5 - Issue Issue 1 Part (2) - Pages 275-281Document7 pagesBJAS - Volume 5 - Issue Issue 1 Part (2) - Pages 275-281Vengky UtamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Contoh Discussion Text Tentang HomeworkDocument8 pagesContoh Discussion Text Tentang Homeworkg3p35rs6100% (1)

- Introduction To Retail LoansDocument2 pagesIntroduction To Retail LoansSameer ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 GDL Web-Site 04 (2021-2022) For 15284Document2 pages07 GDL Web-Site 04 (2021-2022) For 15284ABCDPas encore d'évaluation

- 385C Waw1-Up PDFDocument4 pages385C Waw1-Up PDFJUNA RUSANDI SPas encore d'évaluation

- Practical Modern SCADA Protocols. DNP3, 60870.5 and Related SystemsDocument4 pagesPractical Modern SCADA Protocols. DNP3, 60870.5 and Related Systemsalejogomez200Pas encore d'évaluation

- Colorfastness of Zippers To Light: Standard Test Method ForDocument2 pagesColorfastness of Zippers To Light: Standard Test Method ForShaker QaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dec JanDocument6 pagesDec Janmadhujayan100% (1)

- Introduction To Atomistic Simulation Through Density Functional TheoryDocument21 pagesIntroduction To Atomistic Simulation Through Density Functional TheoryTarang AgrawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Iphone and Ipad Development TU GrazDocument2 pagesIphone and Ipad Development TU GrazMartinPas encore d'évaluation

- Please Refer Tender Document and Annexures For More DetailsDocument1 pagePlease Refer Tender Document and Annexures For More DetailsNAYANMANI NAMASUDRAPas encore d'évaluation

- Kapinga Kamwalye Conservancy ReleaseDocument5 pagesKapinga Kamwalye Conservancy ReleaseRob ParkerPas encore d'évaluation