Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

SDSU Master Thesis: Are MLMs and Pyramids The Same Thing? A Layperson's Guide To Evaluating This Often Misunderstood Business Model

Transféré par

Chris J SnookTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SDSU Master Thesis: Are MLMs and Pyramids The Same Thing? A Layperson's Guide To Evaluating This Often Misunderstood Business Model

Transféré par

Chris J SnookDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Is Network Marketing and Pyramid Selling the same thing?

A laypersons guide to evaluating the pros and cons of this often misunderstood business model.

Author: Chris J. Snook Management 790 Business Administration Department San Diego State University Fall 2005

_______________________________ Primary Advisor: Dr. Alex DeNoble Professor of Management San Diego State University

_______________________________ Secondary Advisor: Dr. Michael Cunningham Professor of Management San Diego State University

Abstract The goal of this project was to explore the academic research surrounding the Network Marketing/Direct Sale Industry as well as Pyramid Schemes, in an effort to locate a model and key characteristics and differences between legitimate and viable NMOs and illegitimate and fraudulent Pyramid Schemes. Historical case law was also researched to locate some landmark decisions that distinguished illegal and unethical direct-selling business models from ethical and sustainable ones. The culmination of this paper sets forth a set of guidelines, based upon the academic and legal research previously conducted, to act as a practical evaluation tool for the everyday layperson who is evaluating one or multiple home-based or NMOs for themselves. The goal is to take the intricate and complex research models, and create a bridge to the real world where most people are looking for a reliable metric to make an investment decision of their time and money into an NMO. These recommendations should be used as a minimum guideline for due diligence if the individual is serious about a low-cost, high-income potential opportunity.

Key Words o o o o o o Network Marketing Pyramid Scheme Direct Selling Organization development Ethics Home-based Entrepreneurs

Table of Contents Abstract Introduction/Industry background The NMO Consumers biggest need The Future of Network Marketing A day in the life of an NMO consumer prospect Landmark court cases and NMO/MLM law Practical evaluation of an NMO opportunity Conclusion NMO/Pyramid Checklist Appendix References i 1 4 6 7 13 18 19 20

ii

Introduction: Network marketing organizations, Multi-Level Marketing (MLM), or NMOs are retailselling (non-store) channels that use independent distributors not only to buy and resell company products at retail, but also to recruit new distributors to grow an independent sales network over time. Methods of compensation vary but often include commissions on personal volumes, group (network) volume, and overrides and bonuses for recruitment that are used to motivate NMO distributors (Coughlan and Grayson, 1998). According to W Gibb Dyer (Dyer, 2001), NMOs were among the most successful organizations in the 1990s with NMO industry sales growing from $30 billion annually to over $90 billion by the year 2000. Since its inception in the 1940s with Nutrilite (credited with being the first NMO) to its current $100+ billion dollar size the NMO industry has faced tons of criticism and scrutiny regarding the ethics of its business practices. This is because of their dark side likeness, the Pyramid Scheme. Pyramid schemes are a distinct version of MLM or NMOs that operate in a manner that is financially and/or culturally unethical (Koehn, 2001). Pyramids or endless-chain distributor schemes ask people to make an investment and, in return, grant them a license to recruit others who, in turn, recruit still others into the scheme. Pyramids are typically distinguished from legitimate MLMs or NMOs when the opportunity to recruit is the product (Koehn, 2001). Industry Background: Koehn goes on to say, in the Journal of Business Ethics 2001, that MLMs are one of the fastest growing types of business, and yet even some of the most prominent MLMs have been accused of being illegal Pyramid schemes. Koehn explains that the National Consumers League reported that in 1996 Pyramid schemes were the number one type of internet fraud, and the fourth most common in 1997.

Coughlan and Grayson (1998) note that an important characteristic of all NMOs (pyramid or legitimate) is that they perform little or no mass media advertising and rely primarily and solely on word-of-mouth advertising for both retail sales and distributor recruitment. The

proponents of NMOs focus on the concept that for experience type goods and services, the consumer prospect will trust information obtained from a friend working in an NMO as more credible than information obtained from media advertising. Proponents also note the low fixed costs of NMOs compared with operating retail stores (Vander Nat and Keep, 2002). This is the basis for the entire NMO concept and is supported by empirical evidence showing that word-ofmouth information from friends and relatives is more influential in consumers purchase decisions than any other form of advertising (Bhattacharya, 1999). How formidable is the NMO industry? Consider that 70% of direct-sales revenues in the world are generated by NMOs (Bhattacharya and Mehta, 2000). NMOs have been growing rapidly in recent years and yet with all of their success they have been tainted by a raging controversy over their practices. Critics focus on illegal or deceptive recruiting practices, false claims of income potential, cult-like social practices, etc. Many of these concerns are legitimate when the company in question falls under the gray areas of MLM/NMO business practices that lean towards the Pyramid classification. These negative attributes are typically non-existent within legitimate NMOs that are not Pyramids. Is this the classic tale of a few bad apples spoiling the whole bunch? If so, then how does someone evaluate an NMO to find out if it is fact a legitimate operation or a Pyramid? Below (Table 1.1) is a list of the several distinctive characteristics of all NMOs (both legitimate and Pyramids). The following portion of this paper uncovers further case law and litmus tests that distinguish between the ethical and non-ethical companies and the conclusion provides a

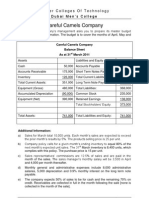

simple (but complete) due diligence checklist for any future network marketer to use in evaluating their target opportunity for its long-term/ongoing viability and ethics. Table 1.1 (adapted and created from Coughlan and Grayson 1998 and Koehn 2001) NMOs/MLMs MODEL TRADITIONAL RETAIL MODEL Lean Organizations (Independent distributors and field leaders) No Advertising Costs/Budget (Rely primarily on word-of-mouth personal selling, and motivating the distributors is crucial. Low operational capital requirements) No Salaries/Performance based pay Multiple Compensation Menu Pay from retail, recruiting, and group volume sources offer multiple opportunities for income generation Recruitment is key to exponential distributor income Depending on the compensation method in this area is where the line is drawn for legal and illegal MLM/NMOs. No recruitment or override opportunity for employee sales reps Wages/less-incentivized pay Standard Compensation Menu Typically salary-only or salary plus singlelevel commission structure Heavy Organizations (W2 employee sales people and managers) Heavy Advertising/Media Budgets (requires less talented and trained sales people, storefronts, and much more operating capital)

The NMO Consumers Biggest Need: The following is an excerpt from Letters to the Editor in Networking Times November/December 2005:

I was recently approached by a woman with a network marketing concept that I would like to do with her, but I am not sure if it is legitimate. The company sells a motivational CD system for $1,500; $500 goes to the company, and the seller profits $1,000. The second phase of the program is selling a conference trip for $8,000, with $3,000 going to the company and $5,000 going to the seller. This approach sounds brilliantbut is this a scam? --Eileen Egyedy Many people today are facing a similar dilemma as they look to find an additional source of income through some type of direct selling, network marketing, or home-based business. They want to know what is good and what is too good to be true. The editor of Networking Times responded to Eileens question with several paragraphs of generic advice due to the vagueness of the company-in-questions business model. Some of the key points he made were to scrutinize the program carefully prior to signing up, and that if the company was paying out 67% of the revenue to the salesperson that longevity of that opportunity may be sacrificed. However, Eileen may or may not know what to look for to evaluate this opportunity for ethical practices, stable business modeling, track record, etc. The editors advice to talk with other distributors who have already succeeded in this company is not necessarily constructive either, since most will only talk positively about the company they are convinced is there opportunity for financial success (Styler, Rob 1998). It is for people like Eileen that this paper is being written, and hopefully many more qualified researchers will continue to do work in this area of opportunity evaluation tools for home-based, NMO entrepreneurs. The Bureau of Labor

Statistics (BLS) estimates that close to 8,500 people per day sign up or start some form of homebased business in the United States. The World Federation of Direct Selling Association

(WFDSA) explains that there are six categories defining distributor types in NMOs.

1)

Wholesale/Discount buyers-they sign up as salespeople merely to buy the companys products at wholesale;

2)

Short Term/Specific Objective-those who join to make extra money before the holidays, etc. and like NMO because of the ease of entry and egress for the saleforce;

3)

Quality of Life Improvers-those who arent earning adequate incomes with their careers and work NMOs part-time to supplement their incomes and improve their lifestyle;

4)

Careerists-Full time direct salespeople who are micro-entrepreneurs running a sales business in partnership with the NMO. distributors fall into the Careerist category; Note: Only 6% of U.S.

5)

Social Contacts-those who join the NMO because they enjoy the company of other people and positive environment of like-minded people;

6)

Recognition-those who sign up because NMOs have no glass-ceilings, and equal opportunity for equal effort without sexual or ethnic preferential treatment.

With the statistics showing that only 6% of people that join NMOs are seeking to launch themselves a full-time business/career (Careerists) it is increasingly important that the other five distributor types who may be less business-savvy by nature or experience level have a simple but complete matrix of evaluating each potential NMO for its ethics, legitimacy, and potential longevity. It is also a business model that has outwardly targeted the part-time individual not the full-time Careerist. This may lend some insight to the theory that in network marketing

businesses only a handful of participants earn significant incomes. That would make sense when

you look at the simple statistic that 94% of distributors in the U.S. only work a few hours per week. The idea that network marketing is a bad business model because only a small percentage of distributors make the high-incomes that are often associated or promoted at NMO opportunity sessions, may not be a clear cut conclusion. Pyramids are bad business and most people lose and never recoup their investment in a Pyramid-type model, however, a legitimate NMO offers any distributor an equal opportunity to earn whatever they work for. Just like any other business model, it may be fair to assume that what you reap you will have sewn first. If you want bigtime returns then you must put in big-time hours (Careerists), whereas if it is your goal to earn some extra money then part-time effort will more than likely produce part-time financial rewards. The Future of Network Marketing Noted economist, Paul Zane Pilzer, author of The Next Millionaires, and White House advisor to two Presidents including Ronald Reagan, is a big fan of Network Marketing. He predicts that $10 trillion dollars of the $50 trillion in new wealth that will be created in the U.S. economy between 2006 and 2016 will represent individuals who rise from entrepreneurial beginnings to become new millionaires. He estimates that approximately ten million people will become new millionaires during this decade-long period, and that many of them will earn their fortunes in Network Marketing. His prediction is carefully thought out in minute detail in his book, as he explains that the economic trends and societal shifts of our entrepreneurial revolution come from the increased migration from corporations to self-employed, home-based businesses; the extraordinary boom in wellness products and services, and the modern worlds profound need for the educational distribution function of word-of-mouth advertising. Pilzer focuses on the positives of increased unemployment in our economy stems from the boom business shift

towards efficiency and the increasing demand for retraining people. Opportunities are more accessible than ever and the playing field has never been more equal. He notes that in his opinion Network Marketing is the best place for this retraining to occur. Whether you buy into Pilzers ideas 100% or only partially, the consensus of the reviewed literature is clear that NMOs will only continue to gain momentum over the next decade, and the need for educating consumers of NMOs on how to pick an opportunity wisely has never been greater than right now. A day in the life of an NMO consumer prospect: Through multiple interviews and personal attendance at twelve separate NMO opportunity overviews (meetings) during primary research of this paper, the following description will describe the recruitment or exposure process most common to those being shown an NMO opportunity (whether it ends up being legitimate or a Pyramid). This anecdotal explanation is important for a clear understanding of the decision environment and external variables that a prospect is dealing with while trying to make an objective decision. The typical recruit or prospect is approached via the phone or in person by a close friend or family member who is excited and has someone they want the prospect to meet who is extremely successful and is looking to expand their business in the prospects local area. They are only in town on Tuesday or Thursday night at their office or hotel and the friend has made a special request that this successful person meet the prospect. The prospect is told that the company is holding a meeting, company overview, or open house and there is an opportunity to meet some top executives of the company. Once they agree to go and support their friend, they end up arriving to the event and being introduced to local superstars as they are escorted into a large room with a group of other people and told that the presentation will begin shortly. The

presentation may run anywhere from 45 minutes to 3 hours and at the conclusion of it, prospects are told that they are in right place at the right time but that knowing that and taking action is the difference between those who get financial success and those who dont. At this point they are handed an application for distributorship and given the option to buy the companys product as a customer, or to be a customer and distributor. After attending a dozen different companys opportunity overviews during primary research, there is one common thread in all cases. The opportunity and product always looks good! There was not one case in which the presentation looked like there was anything to worry about, other than the common concern by prospects that it looks too good to be true. In observation the majority of people either signed up immediately or declined to get involved. After talking with several different self-proclaimed professional network marketers, it was discovered that although some people who decline the first night do sign up at a later date, most people that get involved do so after the first impression. If that is the norm, then it appears that most people are making their decision on emotion/feeling and who showed them the opportunity not the opportunity/company itself. This may not always be a bad thing, however, it does prevent the person from evaluating the company at a level deep enough to determine if the company is at risk of being a Pyramid or short-lived. Another anecdotal finding through primary research of attendance at multiple NMO trainings or corporate rallys in which a large number of distributors were present, is that informal polling of 300 distributors uncovered that 60-70% of distributors originally signed up in their NMO because of the opportunity (potential financial gain), whereas 30-40% of distributors polled originally signed up because it was a great product. This is not a fundamental flaw of NMOs because controlling consumer behavior is not necessarily possible, but it does create a fundamental uphill battle for NMO corporate

executives to consistently make sure the focus is on creating a market for their product, not just the opportunity. Another common thread in all these opportunity sessions was that regardless of the financial success of the various distributors, the enthusiasm for the opportunity was consistent among those in attendance who were apparently earning six-figures or more, or those who had yet to make a sale outside of their immediate family. Due to this one-sided positivity, it became necessary to attempt to quantify the issues and impact related to the inherently high turnover rates amongst their distribution agents in NMOs. An interview with a 19-year network

marketing-industry veteran and self made multi-millionaire with personal experience in legitimate NMOs and NMOs which fell into the Pyramid realm shed light on the fine line between the legitimate and illegitimate NMO, and the challenge for all field agents in discriminating between the two. This distributor confirmed information on the World Wide Scan Network (www.worldwidescam.com), an independent agency that follows the cases, lawsuits, complaints, and or practices of potentially fraudulent or historically fraudulent NMOs, that many times an NMO may fall into the Pyramid realm because of the selling or recruiting practices of certain Big Hitters, (an industry term for people with the ability to recruit huge downlines or organizations), that are not controlled properly by corporate officials. This veteran distributor also focused on the need for training in order to be successful in network marketing. Without a road map to success, it is next to impossible to get there regardless of the industry, however, another common aspect of Pyramids is the requirement or manipulation of downline distributors into paying high costs for extra training, travel, etc. which all generate non-commissionable back-end revenue for the Pyramid owner. Legitimate NMOs will have high quality sales training, business building, and product training support made available to their field distributors,

however, it must be optional and the challenge for NMO corporate officials and field leaders is the fine gray line between providing encouragement and motivation to downline distributors while at the same time maintaining a free will environment. Turnover rates tend to be high in network marketing because people are untrained and unskilled at sales and business building, and fail to make the amount of money they interpreted was possible during their initial exposure to the opportunity. They get frustrated because network marketing wasnt a get rich quick proposition for them, and quit, blaming the opportunity instead of themselves. On the flipside of this coin, is the distributor who pays a couple of hundred dollars (sometimes thousands) per month on training and travel, building an organization of people that do the same, bringing in adequate or sometimes substantial gross income, but whose cash outflow exceeds the cash inflow. Several gung-ho distributors follow a system of success verbatim and earn strong fivefigure monthly incomes, but accumulate equally as much in debt to make it happen. This leads to burnout, frustration, and negative emotions around the principles of the NMO and the industry itself (Styler, 1998). The take home message of the anecdotal research in this message for the prospective distributor is to carefully analyze the minimum overhead of the NMO opportunity, and also any potential hidden fees or necessary extras (training and development, etc.) and factor that into your base monthly operating expenses so that you can compare the revenue ramp up necessary to truly earn a net profit/income that fits your desired goal. In other words, treat network marketing like any other business. It has the potential to be a low-overhead, highly leveraged business, but Pyramids can end up being nothing more than a money pit and school of hard knocks education. (Styler, 1998)

10

The key premise behind a Pyramid scam is the promise of extremely high financial returns with the apparent minimal effort. Jeffrey A. Babener, a leading lawyer and consultant to NMO executives on case law and statutes that govern the NMO industry legitimacy, set forth the following simple distinctions of a Pyramid vs. Legitimate MLM/NMO: Distributors in a network marketing program that are merely buying product to buy into the deal, as opposed to an intention of really making a market for the product, are really working a pyramid scheme, not a legitimate direct selling business (Babener, 2003).

The most famous Pyramid king is probably Luigi Ponzi. Ponzi started his investment scam by putting up $150 and getting ten friends to do the same. He promised the friends a 50% return on investment (ROI) in 90 days or less. He then recruited a second set of friends, many times larger than the first set to each invest $150 with the same promise of 50% ROI. With the new money collected from the second set he repaid the first set of investors their principle ($150) plus the 50% return ($75). The enthused investors naturally promoted the scheme which helped provide the second group of investors the same result, and the scheme mushroomed from there. The Ponzi machine was born, because he had delivered 50% returns in 90 days or less, plus now he was paying a 10% finders fee to those who brought in new investors. The intrigue and genius of the scheme was its simplicity. The problem was that although the original investors (now recruiters) were paid handsomely off of their recruiting efforts, the last ones in found that there was nobody left to recruit and the cash flow stopped, leaving them with a financial loss, while Ponzi and his team had long moved on (Koehn 2001). The David Rhodes electronic chain letter is another example of an illegal Pyramid/Ponzi scheme. It started with a list of 10 people who were all told to send in money to the person at the

11

top of the letters list and to forward the letter to ten bulletin boards, after placing their name on the 10th position of the list. Those who participated were promised they would start receiving money once their name reached the 5th position on the list. Koehn (2001) diagrammed how many people would need to participate before a person would reach the 5th position as follows: Copies in Generation 10 100 1,000 10,000 100,000 1,000,000 10,000,000 Participants Position -10 9 8 7 6 5 Watrous (1999) notes that there are not 10,000,000 bulletin boards in existence, and that even if they substitute real people for bulletin boards that one soon runs out of people. Meanwhile David Rhodes and a handful of others received a lot of $1 in the mail.

12

The commonalities between Pyramid schemes, Ponzi schemes, and chain letters is that in all cases people are enticed into making an investment of money and time by false promises of returns that become increasingly unsustainable as more people are drawn into the scheme. This is the genesis of the idea that only the people at the top make any money. That is true in the case of a Pyramid-type deal, but that is a myth in a legitimate NMO/MLM opportunity. In a legitimate NMO opportunity the financial return is sustainable because the money and commissions are based upon real product sales as well as recruitment. The cash flows to the company and the distributor are based upon true growth and true market acceptance of the product and are therefore sustainable for the duration, and equal to every distributor regardless of when they signed up. The challenge today is that unlike the original Ponzi schemes and chain letters which obviously had no real product, the complex schemes of today have utilized things products such as gold shares, jewelry, etc. to make the scheme look more legitimate (Reese 1999). Koehn (2001) indicates that as long as the returns come primarily from recruiting new people to make investments in jewels and in fees giving them the privelege to do recruiting, the scheme remains fraudulentschemes are unethical because it is not in the public interest to have businesses that are recruitment-rather than product-, centered. Landmark Court Cases and MLM/NMO Law In 2003, during the 108th Congress 1st session meeting on March 12, a Bill cited as the Anti-Pyramid Promotional Scheme Act was presented to The House or Representatives (See Appendix). Congress found that Pyramids, chain letters, and related promotional schemes

constituted a threat to interstate commerce and the financial well-being of the citizens of the United States and should be considered enterprises which 1) finance returns to participants through sums taken from newly attracted participants; 2) promise new participants large returns

13

for their investments, and; 3) involve unfair and deceptive sales tactics, leading to the victimization of unwitting individuals. Congress also recognized that the internet made

Pyramids an international and global threat and that the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals erred in defining a pyramid promotional scheme in Webster v. Omnitrition Intl, Inc. (79F.3d 776; 9th Cir. 1996). The act made it illegal as of March 2004 for anyone to promote via any means of communication (internet, mail, etc.) in interstate and/or foreign commerce, a Pyramid promotional scheme. It also clarified that the Attorney General of each state may bring action against any person who is engaged in or about to engage in any act or practice that constitutes a Pyramid promotional scheme (108th Congress 1st meetingAppendix A) The following list (Table 1.2) of practices are offered up as red flags to potential prospect of NMO opportunities that the company may not be product-centered Table 1.2 (adapted from Koehn 2001) 1) Focusing on growth through the recruitment of new distributors instead of on sales of

Non-harmful products.

2) Requiring substantial upfront fees from those people who are recruited to sell the products. 3) Pressuring recruits to purchase corporate products for their own consumption or to stockpile large

amounts of inventory.

The 1990s represented a period of landmark cases that uncovered and further clarified the legal gray areas that can be abused by Pyramids disguising themselves as legitimate NMOs. In order to understand what gray areas they abused it is important to note the prior court case utilized in NMO court cases prior to the 1990s as the barometer between ethical and unethical practices. FTC v. Koscot (1975) helped create the original (now inadequate) Koscot test which stated: a Pyramid scheme is an arrangement in which participants pay money in return for which they receive (1) the right to sell the product and (2) the right to receive in return for

14

recruiting other participants into the program, rewards that are unrelated to the sale of product to ultimate users. In FTC v. Amway, (1979) the court ruled that Amway was not operating a Pyramid scheme because they were not charging a large sum of money upfront and noted the following provisions and controls in their operating procedures: 1) 70% or all distributor purchases were required to be resold prior to re-ordering (preventing inventory loading), 2) the 10 customer rule which required each distributor to make retail sales to at least ten different customers each month, and 3) the companys buyback policy which offered a minimum 90% refund on all product returned to the company in salable condition (Vander Nat and Keep 2002). This landmark case and ruling is what saved the network marketing industry from extinction and it opened up and legitimized NMOs as an ethical and viable business model. However, it also created loopholes that other cons and scam artists have exploited to feign legitimacy and operate illegal Pyramids (Webster v. Omnitrition, 1996; FTC v. Equinox Intl. Corp, 1999; FTC v. Jewelway Intl, Inc., 1997, FTC v. FutureNet Inc. 1998). For instance, even though Equinox Intl had a documented 70% rule in their operating procedures, as well as a 6-retail sales rule, and required distributors to submit proof of these sales by turning in certificates each month that documented any combination of personal consumption, retail sales, or sales to downline distributors; the companys records (during litigation) only showed collected receipts with a total retail volume of 17% of distributor purchases. Equinox had no method of verifying sales to the public and there was considerable testimony from former distributors that they were encouraged to make up receipts in order to qualify for the 6-retail rule each month (Vander Nat and Keep 2002). In the case of FutureNet, Inc. it was shown that the upfront price of the opportunity was close to 6 times the reasonable market value for the product, and was shown to compensate

15

recruitment of distributors rather than retail sales. Vander Nat and Keep summarized it best in 2002: These FTC settlements reflect the following position: If an organization sells goods or services to the public and the participants in the organization obtain monetary benefits from (1) recruiting new members, and (2) selling the organizations goods and services to consumers, the organization is deemed a pyramid scheme if the participants obtain their monetary benefits primarily from the recruitment rather than the sale of goods and services to consumers (see order provisions and language in FTC v World Class Network, Inc. 1997; FTC v. JewelWay International, Inc., 1997; FTC v. Equinox International, Inc., 1999) The Vander Nat and Keep Formal MLM/Pyramid Model evaluates the level of retailbased rewards in two main ways: (1) direct retail commissions received from the markup above wholesale cost and (2) indirect retail commissions paid to sponsoring distributors for the volume of product sold to the public by their downline of recruits. They do note that in applying their model, however, prosecutors will still encounter issues of market timing and market conditions, because a NMO going through rapid growth may have a large amount of new distributors who have yet to develop retail sales, which can temporarily skew the results to the appearance of potential Pyramid. They note that in such a case it would be prudent to analyze the companys existing distributors for level of retail-based growth and commissions at the non-distributor level (Vander Nat and Keep 2002). Since MLM/NMO companies build their growth on the sale of products as well as the ongoing recruitment of new distributors, it is very possible for the corporation to start off and operate ethically and legitimately, but to degenerate quickly into unethical, fraudulent,

16

recruitment-centered Pyramid schemes. This is why it is important to understand who the corporations top management is and what their business track record inside and outside of the industry is. If they have a clean history for ethical business before, then the opportunity will probably be a long-term viable venture. It is mandatory for the NMO CEOs and top

management to stay on top of the independent field leaders that come into the organization and to strictly enforce its policies and procedures on distribution agents, because one rogue distributor can destroy an otherwise ethical and healthy NMO. It is also imperative to have buyback provisions in place so that distributors do not get stuck with excess product, keep upfront fees minimal for the right to distribute the product, and to make purchases of sales tools, training materials, etc. optional not mandatory. It is common practice for ethical NMOs to frequently terminate the distributorships of individuals who operate their sales teams with a recruitmentcentered vs. product-centered orientation. The most frequented online resource for due diligence or current events regarding potential or obvious scams in network marketing is: www.worldwidescam.com The World Wide Scam Network (WWSN) is not anti-MLM/NMO, and in their position paper they note that although they tend to focus primarily on the wrongdoings of the industry it is merely out of their commitment to eradicating scams, scammers, from the universe. In the paper they are asked the questions Is Network Marketing a viable career choice? Can you really make a decent living selling products through an honest MLM program (to which they responded): In our opinion, the answer is Yes! Here is our theory in this regard. The more honest the company, the people behind it, and the product they are selling, the harder you are going to have to work to make a living wage. This assumes that the product, whatever it

17

is, has real intrinsic value, the company has a fair compensation plan, and their promotions and sales techniques are professional, legal, and ethicalbut honest network marketing is not an easy road to wealth-it is simply another choice available to yoube prepared to work hard as you would with any other job (www.worldwidescam.com 2005). Are there ANY advantages to working in Network Marketing? Sure-the same benefits and risks which would accompany a choice to be independent and self-employed in any other form of sales or serviceAs a self-employed business person you will also be able to legally avail yourself of various income tax benefits, make your own decisions regarding time, money, and effort invested in your business, and control your own destiny in a way that a salary worker never canthe options of residual sales from an expanding downline can be an important income source for your future. Practical Evaluation of an NMO opportunity The Vander Nat and Keep Formal MLM/Pyramid Model confirms that there is more than one way for a firm to be retail based. The common method utilized by legitimate NMOs is to tie upline rewards directly to recruits retail activity, because it is the most provable. Assuming that retail sales are sufficient to cover all costs of goods sold, a compensation model that ties rewards directly to the achieved level of retail sales will secure that all upline rewards are paid by Advanced Retail Commissions vs. Effective Recruitment Rewards. In the defense of legitimate NMOs that may still have more confusing and complex approaches to solving the retail-based question, Vander Nat and Keep note that it can be partly because existing public policy has not clearly articulated the importance of retail sales. They explain through their model and research,

18

that regardless of the method by which a legitimate NMO answers the retail question, it is imperative that the NMO must place their emphasis on selling product to customers outside of the distribution network so that a balance between the expansion of the distributor network and the customer base is maintained. (Vander Nat and Keep, 2002) Conclusion: As stated at the outset of this paper, it is imperative that an ongoing adjustment be made to the evaluation tools utilized by prospects of NMO/MLM opportunities. Below is the final deliverable for the layperson who intends to consume an NMO opportunity under any of the previously mentioned six distributor classifications. This NMO due diligence checklist is a consensus of the most recent academic research regarding NMOs and Pyramids, the formal MLM/Pyramid Model and mathematical analysis developed by Vander Nat and Keep (2002), the legal advice of Jeffrey Babener and Associates (who currently represent 10 of the largest NMOs in the Direct Selling Industry and consult to numerous others over the last twenty years, and the anecdotal research and conversations with several Careerist NMO industry veterans who have been involved in both legitimate and illegitimate opportunities over the course of their careers. Many such veterans interviewed have seen some of their hard work and fortunes evaporate because of the corporate leaders fraudulent practices For the reader the following criteria apply when utilizing this checklist. If you have 0 Nos then the company is solid, with minimal risk of becoming a Pyramid. If you have 1-2 Nos, then dig further and realize they are on the fringe and may not have longevity past 3-5 years; and 3+ Nos, means run fast in the opposite direction! Furthermore, it is advised that you use this tool periodically after you are involved with your chosen company, as marketing plans are often changed along the way, to stay informed as to the legal and ethical direction of the company you are representing.

19

NMO or PYRAMID DUE DILIGENCE CHECKLIST:

NMO COMPANY CHARACTERISTICS CEO/Management Team: Can you access Career Bios of Key management and document the findings? Are their records clean? Product/Price 1) Is it fairly priced to comparable products? Is it high quality and is there a need in the market? Is it proprietary to the company and only available through its distributors? 2) Is the product backed by a strong customer satisfaction refund policy? 3) Would customers buy the companys product if there was no financial opportunity attached to it? Distribution Requirements 4) Can you become a distributor for the company without any major investment other than purchasing a sales kit or demo materials at company cost? ($0-$100) 5) Are qualifications for earning a check small (i.e. maintaining a minimum personal order, and/or 1-10 retail customers per month) 6) Does the compensation plan discourage inventory loading? Enforce a 70% rule prior to repurchase of personal consumption? 7) Does the company have a sufficient buyback policy for for distributors? 8) Are upline and personal commissions paid only on actual product sales to end-users (can be both inside and outside of the network), and avoid paying bonuses or commissions for the mere act of sponsoring or recruiting new distributors? 9) Does the company have a trackable method of ordering to quantify how many retail customers of the product are distributors and non-distributors? 10) Are you safe from risk of a financial loss (above the cost of the product that you can consume) by involving yourself in this opportunity? 11) Do the companys literature and training materials scrupulously avoid claims of income potential or promises of income other than verifiable income levels within its program? (i.e. Do they carefully distinguish what is possible from what is likely?) Training 12) Does the company have substantial (yet optional) training and development programs for new and existing distributors that provides a road map and support system to reach the top promotional levels of the company? (If it is a start up, is their adequate training on product specs and sales in the pipeline for the near future?) YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO YES YES NO NO YES NO YES NO YES NO YES YES NO NO YES NO NMO YES PYRAMID RISK NO

20

APPENDIX

References: Babener, Jeffrey, A. (2003) Is this a Pyramid or a legitimate MLM? www.mlmlaw.com Bloch, Brian; (1996). Multilevel Marketing: Whats the Catch? Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics. Vol. 8-1, 21-30. Bhattacharya, Patralekha. (1999). Network Marketing: A Product characteristic approach. American Marketing Association. Conference Proceedings. Vol 10; 59-60 Bhattacharya, Patralekha and Mehta, Krishna Kumar; (2000). Socialization in Network Marketing organizations: is it cult behavior? Journal of Socio-Economics. Vol. 29: 361374. Brookes, Richard and Little, Victoria; (1997). The new marketing: What does customer focus now mean? Marketing and Research Today. Vol 25-2, 96-106. Chang, Aihwa; Tseng, Chiung-Ni, (2005). Building customer capital through relationship marketing activities; The case of Taiwanese multilevel marketing companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital: Vol 6:2, 253-266 Coughlan, Anne T. and Grayson, Kent, (1998). Network Marketing organizations: Compensation plan, retail network growth, and profitability. International Journal of Research in Marketing. Vol 15, 401-426. Croft, Robin, Cutts, Lindsay and Mould, Patricia; (2000). Shifting the risk: Buyback protection in Network Marketing schemes. Journal of Consumer Policy; Vol 23-2, 177190. Dyer, Jr., Gibb W. (2001). Network marketing: An effective business model for family-owned. Family Business Review Vol 14-2, 97 FTC v. Amway Corp. (1979), 93 FTC 618 FTC v. Equinox Intl Corp (1999), CV-S-99-0969-JBR-RLH (Nevada, August 3) FTC v. FutureNet Inc. (1998), Civ. No. 98-1113 GHK (AIJx) (C.D. Calif., February 17) FTC v. Jewelway International, Inc. (1997), Civ. No. 97-383 TUC JMR (D. Ariz., June 24) FTC v. Koscot Interplanetary, Inc.(1975), 86 FTC at 1180. FTC v. World Class Network, Inc. (1997), No. SACV-97-162 AHS (Eex) (C.D. Calif., February 28).

Ho, Dixon; (2002). An Exploration of Network Marketing as socially embedded exchange. American Marketing Association Conference Proceedings. Vol 13; 251-252 Koehn, Daryl, (2001). Ethical Issues connected with Multi-level Marketing schemes. Journal of Business Ethics: Vol 29;1/2, 153-160. Kustin, Richard A. and Jones, Robert A.; (1995). Research note: A study of direct selling perceptions in Australia. International Marketing Review. Vol 12-6, 60-68. Mswell, Pumela and Sargeant, Adrian; (2001). Modeling distributor retention in network marketing organizations. Market Intelligence & Planning; Vol 19-6,7; 507-514. Networking Times: Moving the Heart of Business. (2005) Nov/Dec, Vol 4 Issue 6, p8 Pilzer, Paul Zane,.(2004) The Next Millionaires. Pratt, Michael G.; (2000). The Good, the Bad, and the Ambivalent: Managing Identification among Amway Distributors. Administrative Science Quarterly. Vol 45-3, 456-527 Pratt, Michael G, and Rosa, Jose Antonio. (2003). Transforming work-family conflict into commitment in network marketing organizations. Academy of Management Journal. Vol 46-4, 395. Reese, S. (1999) Securities Law and MLM-Whats the Deal? MLM Law Library at www.mlmlaw.com Styler, Robert (1998) Spellbound: My Journey Through a Tangled Web of Success. Sandy Creek Publishing. Vander Nat, Peter J and Keep, William W.; (2002). Marketing Fraud: An approach for differentiating Multi-level Marketing from Pyramid schemes. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. Vol 21-1, 139-151. Watrous, S. (1999) www.mlmlaw.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hindustan Unilever Marketing Strategies and PoliciesDocument46 pagesHindustan Unilever Marketing Strategies and Policiesroma4321Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-MLM ZealotsDocument52 pagesAnti-MLM ZealotsLen ClementsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Miracle Morning For Network Marketers Grow Yourself FIRST To Grow Your Business FAST (Elrod, Hal Petrini, Pat Corder, Honoree)Document212 pagesThe Miracle Morning For Network Marketers Grow Yourself FIRST To Grow Your Business FAST (Elrod, Hal Petrini, Pat Corder, Honoree)NAMORY FOFANAPas encore d'évaluation

- Fast Start To Success Manual PDFDocument32 pagesFast Start To Success Manual PDFharrybelloisPas encore d'évaluation

- MLM Amway StoryDocument35 pagesMLM Amway StorymlmstarPas encore d'évaluation

- BSCM 1 PDFDocument54 pagesBSCM 1 PDFSerap DemirPas encore d'évaluation

- Transportation$Assignmnet-Review ProblemsDocument4 pagesTransportation$Assignmnet-Review Problemsilkom12Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mrs. StoneDocument11 pagesMrs. StonespanischkindPas encore d'évaluation

- Retail Formats of Khaadi and Amir AdnanDocument32 pagesRetail Formats of Khaadi and Amir AdnanWaqas Cheema63% (8)

- Case Study 1 Ethics and The ManagerDocument2 pagesCase Study 1 Ethics and The ManagerTino AlappatPas encore d'évaluation

- The Top Multilevel Marketing System: Strategies for Building a Successful BusinessD'EverandThe Top Multilevel Marketing System: Strategies for Building a Successful BusinessPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Network MarketingDocument6 pagesWhat Is Network MarketingMatthew NovelozoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Secrets to Succeeding in Network Marketing Offline and Online: How To Achieve Financial Success Selling Network Marketing Products And ServicesD'EverandThe Secrets to Succeeding in Network Marketing Offline and Online: How To Achieve Financial Success Selling Network Marketing Products And ServicesÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- Pyramid&NetworkMarketing PDFDocument8 pagesPyramid&NetworkMarketing PDFCharaka Chathuranga VithanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vignan Jyothi Institute of Management: Submitted byDocument17 pagesVignan Jyothi Institute of Management: Submitted byMahesh Goyal100% (1)

- Alliance in Motion Global Company PoliciesDocument31 pagesAlliance in Motion Global Company PoliciesManuel Ledda Bautista100% (2)

- Its Your Right: Beginning But Once You Trust Him, You Will Be Able To Apply What He SaysDocument3 pagesIts Your Right: Beginning But Once You Trust Him, You Will Be Able To Apply What He SaysMoh G Al-ghamdiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Enhanced Qnet Vietnam'S Compensation PlanDocument18 pagesThe Enhanced Qnet Vietnam'S Compensation PlanDr Joby JosephPas encore d'évaluation

- Network Marketing: Ashawin KherDocument37 pagesNetwork Marketing: Ashawin KhermayurkasalePas encore d'évaluation

- Network Marketing Sales ProcessDocument65 pagesNetwork Marketing Sales ProcessTRAINER HDI KEDOYAPas encore d'évaluation

- WFDSA Annual Report 112718Document17 pagesWFDSA Annual Report 112718Oscar Rojas GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Multi Level MarketingDocument27 pagesMulti Level Marketingabhi_lbsim100% (1)

- Social Media Bootcamp - Workshop AgendaDocument4 pagesSocial Media Bootcamp - Workshop AgendaTodd LohenryPas encore d'évaluation

- Leadership Summit December 2010Document83 pagesLeadership Summit December 2010harryvaranPas encore d'évaluation

- Amway-Direct Selling and Supply ChainDocument3 pagesAmway-Direct Selling and Supply ChainSachin R. KanojiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Network Marketing by Robert Kiyosaki Donald TrumpDocument5 pagesWhy Network Marketing by Robert Kiyosaki Donald Trumpneil allan maryPas encore d'évaluation

- Invite ArticleDocument3 pagesInvite ArticleSirvan Moulaei100% (1)

- Qnet Company PlannerDocument6 pagesQnet Company PlannerKool Live SmartiePas encore d'évaluation

- NDOP-BWW Presentation - 093914Document20 pagesNDOP-BWW Presentation - 093914MAHAMMAD ANWAR ALIPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Binary MLM SoftwareDocument2 pagesWhat Is Binary MLM SoftwareShruti Bansal0% (1)

- NetworkingDocument50 pagesNetworkingRuxPas encore d'évaluation

- N Target To Mastery: Managing Your ProspectsDocument8 pagesN Target To Mastery: Managing Your ProspectsMichael HengPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Project PLAN: No. Task Person Todoandwhatislefttodo (+profa's Advice)Document4 pagesMarketing Project PLAN: No. Task Person Todoandwhatislefttodo (+profa's Advice)Gavrus AndreeaPas encore d'évaluation

- CRMDocument31 pagesCRMabhisht89Pas encore d'évaluation

- MLM PresentationDocument9 pagesMLM Presentationapi-643117257Pas encore d'évaluation

- BizB9 ProfileDocument72 pagesBizB9 ProfilePawan Prakash SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Chapter 19 Managing Personal CommunicationDocument32 pagesCase Study Chapter 19 Managing Personal CommunicationNur FateyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Network MarketingDocument6 pagesNetwork MarketingkomalPas encore d'évaluation

- A Chance To Make Money Doing Something I Love: Kim KlaverDocument8 pagesA Chance To Make Money Doing Something I Love: Kim KlaverRichard Oluseyi AsaoluPas encore d'évaluation

- How Fuck King MenDocument2 pagesHow Fuck King MenNgô TuấnPas encore d'évaluation

- What Are 40 Life Changing Success Tips? (3-5) 40 Success Tips!Document4 pagesWhat Are 40 Life Changing Success Tips? (3-5) 40 Success Tips!Martin F LucasPas encore d'évaluation

- Network MarketingDocument3 pagesNetwork Marketingavijitcu2007Pas encore d'évaluation

- MLM News Direct Selling Facts, Figures and NewsDocument9 pagesMLM News Direct Selling Facts, Figures and NewsNuuraniPas encore d'évaluation

- TVI Express PresentationDocument70 pagesTVI Express PresentationNito Fonacier II100% (1)

- Social Media Preso FullDocument65 pagesSocial Media Preso FullmcmawebPas encore d'évaluation

- Diamond Rush GuideDocument11 pagesDiamond Rush GuideJohn TurnerPas encore d'évaluation

- SSRN Id1751657Document23 pagesSSRN Id1751657Kamran LakhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- QNet FAQDocument2 pagesQNet FAQDeepak GoelPas encore d'évaluation

- MLMDocument27 pagesMLMVanita AggarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Benefits of Social Media in Network MarketingDocument3 pages3 Benefits of Social Media in Network MarketingDela Cruz FamilyPas encore d'évaluation

- Network Marketing ProjectDocument32 pagesNetwork Marketing ProjectVinay Singh82% (11)

- 2019 Active World Team 1-Year Flyer Opt2Document1 page2019 Active World Team 1-Year Flyer Opt2JackDi75% (4)

- Herbalife Products Introduction Version 2Document34 pagesHerbalife Products Introduction Version 2A AlamPas encore d'évaluation

- Credibilities PDFDocument60 pagesCredibilities PDFYamuna j100% (1)

- 3 Reasons Most Businesses Don't Reach 6 FiguresDocument2 pages3 Reasons Most Businesses Don't Reach 6 FiguresMoises A. AlmendaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Amway GIP2014-15booklet PDFDocument24 pagesAmway GIP2014-15booklet PDFprakash kakaniPas encore d'évaluation

- DSA Fact Sheet 2010Document1 pageDSA Fact Sheet 2010Kevin ThompsonPas encore d'évaluation

- 10X Lead System - Social and Content EmailsDocument14 pages10X Lead System - Social and Content EmailsnordinPas encore d'évaluation

- QNet TimelineDocument7 pagesQNet TimelineShaimaa Abdel KhalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Multi-Level Marketing: Presented By: Rowelyn D. EnajeDocument10 pagesMulti-Level Marketing: Presented By: Rowelyn D. EnajeWelyn Dael Enaje100% (1)

- La Beuna VIDA - AssignmentDocument19 pagesLa Beuna VIDA - AssignmentLeo Vambe100% (1)

- Entrepreneurship Seminar - Jun 2013Document96 pagesEntrepreneurship Seminar - Jun 2013BookwormatworkPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study of Network Marketing Adopted by Phoenix InfraDocument17 pagesA Study of Network Marketing Adopted by Phoenix InfraDeepankar ShendePas encore d'évaluation

- Autoresponder For BusinessDocument12 pagesAutoresponder For BusinessVOIP telephone servicePas encore d'évaluation

- Skin&BeyondDocument16 pagesSkin&BeyondBenjamin Paolo GogoPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods To Initiate VenturesDocument16 pagesMethods To Initiate VenturesRaquel GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Eicher Motors - Group 5Document8 pagesEicher Motors - Group 5akirocks71Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tutorial Partnership LawDocument7 pagesTutorial Partnership LawLoveLyzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nitin Ghai Neeraj Jain Shubham Gupta Mohit Gupta Garima SinghDocument30 pagesNitin Ghai Neeraj Jain Shubham Gupta Mohit Gupta Garima SinghShubham GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Roxana Nicoleta Filip-CVDocument3 pagesRoxana Nicoleta Filip-CVroxanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Buffet 131209045007 Phpapp01Document72 pagesBuffet 131209045007 Phpapp01kumar satyam100% (1)

- Ogdcl Rig Tor Rm-4573Document8 pagesOgdcl Rig Tor Rm-4573Ahmed Imtiaz RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Brian Tracy - The Universal Laws and YouDocument39 pagesBrian Tracy - The Universal Laws and YouKonstantinos A. Smouliotis100% (2)

- Feasibility Slaughter House - Punjab 2011Document36 pagesFeasibility Slaughter House - Punjab 2011YasinPas encore d'évaluation

- SCM QP EFF Based Pricing StrategyDocument47 pagesSCM QP EFF Based Pricing StrategysreeharireddylPas encore d'évaluation

- Product Life CycleDocument11 pagesProduct Life CycleASHWINI SINHAPas encore d'évaluation

- Moonka Auto - Team 5Document3 pagesMoonka Auto - Team 5manee4uPas encore d'évaluation

- Customer Profitability Analysis: F.M.KapepisoDocument9 pagesCustomer Profitability Analysis: F.M.Kapepisotobias jPas encore d'évaluation

- QB Enterprise Solutions Bookkeeper Job Description PDFDocument3 pagesQB Enterprise Solutions Bookkeeper Job Description PDFnaumanahmad867129Pas encore d'évaluation

- LiloDocument44 pagesLiloapi-355708440Pas encore d'évaluation

- Biskitta (PAK) - Marketing ProjectDocument35 pagesBiskitta (PAK) - Marketing ProjectGirija RamdasPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment Budgeting 1 WorksheetDocument9 pagesAssignment Budgeting 1 WorksheetSultan Bin OboodPas encore d'évaluation

- The Motley Fool "Options Edge" HandbookDocument11 pagesThe Motley Fool "Options Edge" Handbookapi-25895447100% (4)

- Accounting 6-7Document8 pagesAccounting 6-7janePas encore d'évaluation

- Plunketts Airline Hotel and Travel Industry Almanac-Plunkett Research (2011)Document510 pagesPlunketts Airline Hotel and Travel Industry Almanac-Plunkett Research (2011)rajat sharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Account Question 12Document5 pagesAccount Question 12Kapildev SubediPas encore d'évaluation

- ERP - Functional SpecificationDocument22 pagesERP - Functional SpecificationUsman AbbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Information Systems Strategic Plan (Issp) For Royce Racing EnterprisesDocument7 pagesInformation Systems Strategic Plan (Issp) For Royce Racing EnterprisesSabrinaPas encore d'évaluation