Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

501 Teachers: The Key To EdTech Synthesis Paper

Transféré par

kris_meslerTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

501 Teachers: The Key To EdTech Synthesis Paper

Transféré par

kris_meslerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

TEACHERS: The Key Component to a Successful Educational Technology Program Kris Mesler EDTECH 571 Introduction to Educational Technology

Boise State University August 10, 2007

The Challenge Why dont teachers innovate when they are given computers? One of the greatest challenges in the educational technology realm is that of establishment and implementation of strategies to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for teachers to effectively use technology as an instructional tool. The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) requires 25% of state federal technology funding to be allocated for professional development, demonstrating the impact of professional development on the effective integration of technology into curriculum and instruction (Cradler, Freeman, Cradler & McNabb, 2002). Emphasis in this area underscores the importance of the teacher in the successful implementation of a successful educational technology program. Early expectations regarding computer use have not been realized due to two factors. The first was a mistaken notion that when computers are introduced, they lighten the load of teachers. The second factor is inadequate training of teachers in the use of computers, often rendering computers more trouble and expense than they are worth. As a result, some computers have ended up in the closets (Stratham & Torell, 1996). Many studies have cited the importance of the role of the teacher in the educational technology program. The report When Powerful Tools Meet Conventional Beliefs and Institutional Constraints: National Survey Findings on Computer Use by American Teachers (Becker, 1990), concluded that although computer availability is important, the most important factors determining whether teachers use computers effectively are planning time and teacher attitudes, style, and background. Miller and Olsen (1994) argued that the existence of innovative practices associated with the introduction of the computers in the classroom has less to do with the advent of technology than with the teachers pre-existing conception of practice. They also said that a teachers prior practices and routines influence computer use

in powerful ways. Project Homeroom (Hecht, et al., 1993) states that several key issues were identified as a result of the Project, the first being that innovation of this sort takes time to accomplishtime for teachers to learn about technology and time for teachers and students to accept change. Zoni (1992) notes that the most important element in the success of a program is providing adequate and on-going teacher training, on site, including adequate instruction and practice. Despot (1992) says that until teachers have access to technology, the computer will continue to be viewed as a supplement instead of an integral part of the learning process. Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow (Dwyer, 1994) observes that the greatest student advances seem to occur in classes where teachers are beginning to achieve a balance between the appropriate use of both direct instruction strategies and collaborative, inquiry-driven knowledge-construction strategies. In general, as the level of implementation and teacher integration increased, so did student performance and student and teacher effort (Van Dusen & Worthen, 1995). Key Components of the Successful Teacher Who Uses Technology Types of Teachers Three key components used in finding the teacher who uses technology effectively include determining the type of teacher involved, the use of constructivist pedagogy, and the implementation of successful teacher characteristics. A study done through the Center for Research on Information Technology and Organizations at the universities of California-Irvine and Minnesota (Becker & Riel, 2000) concluded that there were four types of teachers in classrooms today. They include teacher leaders, teacher professionals, interactive teachers, and private practice teachers. Some teachers believe work that takes place in their classrooms is essentially a private, individual practice. They are content to let curriculum, policy or standards decisions be made by outside experts and accept that teachers may teach in different ways, even though they think

some are ineffective or wrong. Others view their responsibilities as beyond the classroom teaching into the larger community of educators and administrators. They try to help other teachers be successful and to influence how teaching occurs in other places. These two separate views are the extremes of teaching. Other teachers fit somewhere in between. Three Professional Engagement measures were used to determine the type of teacher in the classroom through survey questions. Teachers who scored high in the areas of (1) within-school/informal interactions, (2) beyond-school contacts and (3) leadership were defined as Teacher Leaders. Teacher Leaders view their relationship to other educators within and beyond the school as an important determinant of the quality of student learning in the classroom (Glazer, 1999 as cited in Becker & Riel, 2000). They are more likely to build a professional identity than those engaged in private practice teaching. A typical Teacher Leader would be one that has a self-contained classroom. She (He) may or may not have attended a selective college and maintained a high GPA. She has also recently taken at least one graduate course for credit. At least once a week, she observes another teachers classroom and is observed herself by other teachers. She talks frequently with other teachers regarding how to teach a particular concept or about subject matter content. Several of those conversations have to do with planning group projects and the use of technology. She is also active in committee work and workshops and communicates with teachers in other places using electronic mail. She most likely has served as a workshop or conference leader and as a mentor to other teachers. Teacher Professionals have many of the same qualities as the teacher leader, but to a lesser degree. Their concern about what happens in other classrooms becomes part of their own definition of being successful. When teacher with a professional work-orientation experience pressure from school, district, or state recommendations that contradict their studied beliefs about good teaching, they work collectively to formulate a collective but

substantive response rather than expecting each teacher to resolve the conflict individually. The differences in peer interaction and leadership behavior between the top two categories of Professional Engagement, Teacher Leaders and the Teacher Professionals are not as great as the differences between both those groups and the remaining teachers. In both groups, these are teachers who demonstrate a sense of their responsibility to engage in a regular interchange with an educational community beyond their classroom students. Both categories are referred to as Professionally Engaged Teachers (Becker & Riel, 2000). The typical Teacher Professional has taken a great deal of college-level coursework over time, having not only a masters degree, but also credits beyond. She (He) has a high level of interaction with teachers at her own school, but fewer with teachers at other schools. She talks about her subject matter with other teachers regularly, and has at least weekly discussions with them about teaching concepts, and she visits other classrooms to observe teaching as well. She participates on committees and attends workshops regularly. She has presented at workshops occasionally and informally mentors other teachers at her school. Her teaching is observed occasionally by others, and does not e-mail other teachers as often as a Teacher Leader would. Interactive Teachers scored medium or higher in at least one of the three Professional Engagement areas and nearly 80% of them scored high in at least one area. However, in at least one area, Interactive Teachers failed to meet a medium standard (Becker & Riel, 2000). Interactive Teachers do engage in substantial interaction with other teachers, but do not do so both in school and beyond school and in a way that their professional leadership is publicly visible. A typical Interactive Teacher is less professionally engaged than either a Teacher Leader or a Teacher Professional. She (He) attended a relatively unselective college and had a modest GPA, but is still taking courses for credit. She doesnt observe other teachers

classrooms often, but spends regular time talking informally with other teachers about teaching methods, technology, and subject-matter issues. She attends conferences and workshops during the school year, but does not participate on committees or any other leadership positions. She is a fairly new teacher and the activities she is involved in may lead to becoming more of a leader and participant in Professional Engagement. Private Practice Teachers have little time for meetings, conferences, or other forms of professional engagement. They use the textbooks and other teaching resources they are given or which they gather themselves, and construct their own instructional practices without much input from others. They may be afraid to share needs with other teachers and instead choose to spend much of their time in their own classroom. Almost half of all Private Practice Teachers did not meet even medium standards for Professional Engagement in any area and 85% of them did not meet a high standard in any area (Becker & Riel, 2000). The typical Private Practice Teacher has many years of teaching experience and is middle aged. She (He) attended a moderately selective college and attained modest grades but does not have an advanced degree or many graduate credits. She rarely observes other teachers or is observed by others. She has some conversations with teachers, but they are of a personal rather than professional nature. She attends workshops frequently, but does not communicate with teachers using e-mail. She does not show any interest in leadership positions and there are few indications that she is involved with her peers, although she has taught for several years. At the conclusion of the study, only 2% of teachers in the study met the criteria for being a Teacher Leader, while another 10% fell into the Teacher Professional category. Interactive Teachers constituted 29% of the remainder, while 58% were classified as Private Practice Teachers (Becker & Riel, 2000). Successful educational technology professional development must reach the 87% of those in the Interactive Teacher and Private Practice

Teacher categories, as those in the Teacher Leader and Teacher Professional categories tend to be active learners in the field of educational technology. Constructivist vs. Transmission Teaching There are two contrasting styles of teaching philosophy that must be taken into consideration when developing educational technology strategies for the classroom. A transmission view of good teaching includes direct instruction and repetitive skills practice around a fixed curriculum. The opposite constructivist view sees learning as knowledge construction through collaborative projects and problem solving tasks. A thriving educational technology program is best accomplished by those teachers with a constructivist view of learning. The active learning dimension of constructivist practices contains the elements: (1) the use of student projects, (2) small group work, and (3) an infrequent use of direct instruction activities. Teachers using constructivist practices ask students to write reflectively, pose questions that call for deep thinking, assign problem-solving tasks and organize their classroom time to promote meaning-making among students, all part of an active learning program. In an educational technology program, constructivist teachers use many computer experiences to accomplish active learning and they use electronic mail, multimedia authoring software, and presentation software personally as well. Successful Teacher Characteristics Three characteristics of teachers that were significantly linked with successful integration of technology innovations were: Technology Proficiency in using hardware and software, and in understanding the conditions that support technology use. Teachers must be able to set up the infrastructure required for the assignments they will give to students. Compatibility of teaching style, content, and the software and hardware. Teachers who saw an intimate connection between the selected technology

and their curriculum were more likely to implement their innovations successfully. Social awareness of the school culture and organization. Teachers need to be aware of the technology use patterns of other teachers in order to schedule hardware and software needed to complete a project (Zhao, Pugh, Sheldon, Byers, 2001).

What do teachers need to consider in order to be successful in technology integration? Teachers must be technologically proficient. Most teachers realize their level of knowledge in the use of technology. When new programs become available, they must take steps to become proficient in the new hardware or software in order to concentrate on the teaching process, rather than their learning of technology. Teachers must also face any anxiety they have about technology in general, whether because of their age and experiences when growing up, or due to demographics and the availability of local technology. Also related to this anxiety are the teachers attitudes and beliefs toward technology in education. If teachers do not see the need and uses of technology in the classroom, they will be unwilling to make it a part of their daily routine. Previous and planned professional development emphasizing the use of technology in the classroom is of the utmost importance in order to spark the creative interest of the teachers. As stated earlier, those teachers with the constructivist style of teaching will be better suited to successfully implementing a viable technology program. Recognition of their own style of teaching will help teachers realize what they are missing in their own classrooms, and encourage them to boost their expertise in the field. Implications for Educators, Administrators, and other Decision Makers Educators and decision makers can take several steps to support technology innovations. They include: 1. Enabling teachers to select technologies that easily integrate into their teaching style and the school culture.

2. Providing opportunities for in-service and pre-service teachers to reflect upon their attitude toward computer technologies, and to clarify their preferred instructional strategies. 3. Providing hands-on practice with the integration of technology and curriculum objectives. 4. Enabling teachers to understand the value of using technology as a means rather than as an end. 5. Involving school personnel in planning and implementing technology innovations in classrooms. 6. Considering the real limitations that exist in contemporary classrooms. 7. Taking small, evolutionary steps when integrating with curricula, so teachers may experience success rather than frustration with the technology. 8. Providing Internet connections in classrooms, rather than in computer labs that must be reserved far in advance. 9. Identifying and enabling mentors who can model technology integration and provide guidance specific to the curriculum needs of the teacher/learner. Administrators can also influence the success of technology innovations by: 1. Supporting the formation and implementation of Acceptable Use Policies for responsible use of the Internet. 2. Funding and facilitating access to technical assistance for equipment maintenance and Internet connectivity. 3. Providing staff development and mentoring opportunities for teachers to learn to use technology with curriculum objectives (Zhao, Pugh, Sheldon, Byers, 2002). Conclusion- The Continuing Challenge Many of the steps that educators, decision makers, and administrators may take evolve as the world of technology evolves. Professional development is a crucial element in any coordinated approach to improving technology use in schools, and there needs to be continuing improvement and expansion of the kinds of training options available to teachers. Other teacher enhancements that should also be pursued in the search for the perfect educational technology program are improvement in the preparation of new teachers,

including their knowledge of how to use technology for effective teaching and learning; increasing the quantity, quality, and coherence of technology-focused activities aimed at the professional development of teachers; and improving real-time instructional support available to teachers who use technology (U. S. Department of Education, 2000). The important role of the teacher in educational technology cannot be ignored. Teaching remains centered on the teacher, and computers are employed as the tools that they are. The use of computer technology will not lead to the replacement of teachers; instead, effective use of computers leads to consistently good methods and materials for the benefit of teachers as well as students. With proper implementation, computer technology does not remove all challenges nor does it replace teachers; but it can lead to transformation in the classroom, creating a superior environment for learning (Stratham & Torell, 1996). Teachers must have adequate motivation, interest, and training to prepare successful instruction using computers.

References Becker, H. J. (1991). When powerful tools meet conventional beliefs and institutional constraints: National survey findings on computer use by American teachers. The Computing Teacher (May 1991) Baltimore, MD. Center for Research on Elementary and Middle Schools. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 337 142). Retrieved August 9, 2007 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ430225 Becker, H. and Riel, M. (2000). Teacher professional-engagement and constructivistcompatible computer use (TLC report 7). Teaching, Learning, and Computing:1998 National Survey (TLC). Center for Research on Information Technology and Organizations, University of California, Irvine. Retrieved August 1, 2007 from http://www.crito.uci.edu/tlc/findings/report_7/startpage.html Cradler, J., Freeman, M., Cradler, R. and McNabb, M. (2002, September). Research Implications for Preparing Teachers to Use Technology. Learning and Leading with Technology Vol. 30 No. 1. International Society for Technology in Education, Washington, D.C. Retrieved August 1, 2007 from http://www.iste.org Despot, P. C. (1992). Nurturing the communication abilities of second grade students by using notebook computers to enhance the writing process. Practicum Report, Nova University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 351 700). Retrieved August 9, 2007 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=ED351700 Glazer, J. (1999, April). Considering the professional community: An analysis of key Ideas, intellectual roots, and future challenges. Paper presented at the American Education Research Association, Montreal, Canada. Hecht, J. B., Dwyer, D. J., Roberts, N. K., Schoon, P. L., Kelly, J., Parsons, J., Nietzke, T., and Virlee, M. (1993). Project Homeroom second year experience: A final report on the project in the Maine East High School, New Trier High School, Amos Alonzo Stagg High School. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 366 638). Retrieved August 9, 2007 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=ED352029 Miller, L., and Olson, J. (1994). Putting the Computer in Its Place: A Study of Teaching with Technology. Journal of Curriculum Studies, Vol. 26 No. 2. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. EJ 493 884). Retrieved August 9, 2007 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ493884 Stratham, D.S. and Torell, C.R. (1996). Computers in the classroom: the impact of technology on student learning. Boise, ID: Army Research Institute. U. S. Department of Education (2000). The national technology education plan. e-Learning: Putting a world-class education at the fingertips of all children. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved August 1, 2007 from http://www.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/techconf00/report.html Van Dusen, L. M., and Worthen, B. R. (1995). Can integrated instructional technology

transform the classroom? Educational Leadership, Vol. 53 No. 2. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. EJ 513 394). Retrieved August 9, 2007 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ513394 Zhao, Y., Pugh, K., Sheldon, S., and Byers, J. (2002). Conditions for classroom technology innovations: Executive summary. Teachers College Record, Vol. 104 No. 3, East Lansing, MI. Retrieved August 1, 2007 from http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentID=10850 Zoni, S. J. (1992). Improving process writing skills of seventh grade at-risk students by increasing interest through the use of the microcomputer, word processing software, and telecommunications technology. Practicum Report, Nova University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 350 624). Retrieved August 9, 2007 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=ED350624

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- 592 Rationale PaperDocument33 pages592 Rationale Paperkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- 505 Final Evaluation ReportDocument14 pages505 Final Evaluation Reportkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- 513 Pythagorean Worked ExamplesDocument15 pages513 Pythagorean Worked Exampleskris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- 501 Digital Divide MemoDocument4 pages501 Digital Divide Memokris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

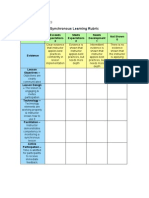

- 523 Synchronous Lesson RubricDocument2 pages523 Synchronous Lesson Rubrickris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- 506 UK Unit JustificationDocument19 pages506 UK Unit Justificationkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- 505 Hawaii ScenarioDocument7 pages505 Hawaii Scenariokris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- 504 Cognitive Theory Synthesis PaperDocument16 pages504 Cognitive Theory Synthesis Paperkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- 504 Annotated BibliographyDocument7 pages504 Annotated Bibliographykris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- 506 Travel Brochure RubricDocument2 pages506 Travel Brochure Rubrickris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- 501 Dark Side SpeechDocument7 pages501 Dark Side Speechkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- 505 Final Evaluation ProposalDocument6 pages505 Final Evaluation Proposalkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Moderator: Invite Classmates To Virtual Classroom and Point Out Elements ofDocument20 pagesModerator: Invite Classmates To Virtual Classroom and Point Out Elements ofkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- 503 Proportion Project HandoutsDocument62 pages503 Proportion Project Handoutskris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- 506 UK Visual ContentDocument2 pages506 UK Visual Contentkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- 503 Program Development ReportDocument28 pages503 Program Development Reportkris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- 597 Basics of Design Final Project PlanDocument41 pages597 Basics of Design Final Project Plankris_meslerPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- Homeschooling Pros and ConsDocument9 pagesHomeschooling Pros and ConshzPas encore d'évaluation

- Working Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesWorking Lesson Planapi-623457578Pas encore d'évaluation

- ESP Course Syllabus Focuses on English Language SkillsDocument7 pagesESP Course Syllabus Focuses on English Language SkillsEmenheil Earl EdulsaPas encore d'évaluation

- English7 Q1 M1 W1Document22 pagesEnglish7 Q1 M1 W1donabelle mianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum VitaeDocument2 pagesCurriculum VitaeEvita EsguerraPas encore d'évaluation

- IJEAP Volume 10 Issue 1 Pages 35-53Document19 pagesIJEAP Volume 10 Issue 1 Pages 35-53firman alam sahdiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Field Study 3 Compilation on Technology in Learning EnvironmentsDocument11 pagesField Study 3 Compilation on Technology in Learning EnvironmentsJennyrose AmoguisPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundations of Education SB Year 1Document328 pagesFoundations of Education SB Year 1Jorah Sanchez100% (3)

- Reading Remediation PlanDocument3 pagesReading Remediation PlanWinerva Pascua-BlasPas encore d'évaluation

- Digos City Senior High School: Department of EducationDocument2 pagesDigos City Senior High School: Department of EducationJULIE CRIS CORPUZPas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge Primary Global Perspectives Teacher Guide 0838 - tcm142-469225Document45 pagesCambridge Primary Global Perspectives Teacher Guide 0838 - tcm142-469225Fahma Abdulle100% (5)

- Teacher-Directed Violence and Stress: The Role of School SettingDocument8 pagesTeacher-Directed Violence and Stress: The Role of School SettingAnel RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- 3HEM311 Student GuideDocument16 pages3HEM311 Student GuidekhangegPas encore d'évaluation

- Education-School MattersDocument113 pagesEducation-School MattersEphraim PrycePas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Negative Effects of TechnologyDocument6 pagesThe Negative Effects of TechnologyDonald Jhey Realingo Morada100% (1)

- Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Secondary School Teachers in Klang, MalaysiaDocument4 pagesDepression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Secondary School Teachers in Klang, MalaysiaAhmad Shahril Ab HalimPas encore d'évaluation

- M6 in MC PEH3Document13 pagesM6 in MC PEH3jeno purisimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Q N Performance Strategists Edid 6502 Group ProjectDocument40 pagesQ N Performance Strategists Edid 6502 Group Projectapi-597475939Pas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Lesson Plan Subject:: Form Class Date Week Time Venue Attendance ThemeDocument3 pagesDaily Lesson Plan Subject:: Form Class Date Week Time Venue Attendance ThemeHafizah PakahPas encore d'évaluation

- Ms 6 Science SyllabusDocument4 pagesMs 6 Science Syllabusapi-322611900Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Guide For Catch Up Friday - National Reading ProgramDocument3 pagesTeaching Guide For Catch Up Friday - National Reading Programjoey mataac100% (15)

- FINAL GGUSD Student Bill of RightsDocument6 pagesFINAL GGUSD Student Bill of Rightspiu uPas encore d'évaluation

- ETEC 532 - Vignette AnalysisDocument4 pagesETEC 532 - Vignette AnalysisCamille MaydonikPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Survey QuestionnaireDocument10 pagesSurvey QuestionnaireTricia Mhae F. MoralesPas encore d'évaluation

- PRE and POST Class Observation ConferenceDocument6 pagesPRE and POST Class Observation ConferenceIsrael Asinas94% (17)

- The Bull's Eye - May 2012Document11 pagesThe Bull's Eye - May 2012dbhsbullseyePas encore d'évaluation

- How To Involve Various Educational Stakeholders in Education ImprovementDocument2 pagesHow To Involve Various Educational Stakeholders in Education ImprovementNel RempisPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of E-Library On Student Academic PerformanceDocument31 pagesImpact of E-Library On Student Academic Performanceadekanmiadeolu82% (22)

- The Role of Teachers in Improving School Education: T.PushpanathanDocument4 pagesThe Role of Teachers in Improving School Education: T.PushpanathanPushpanathan ThiruPas encore d'évaluation

- A Thesis Manuscript of Group 5 Complete 3Document87 pagesA Thesis Manuscript of Group 5 Complete 3Ana MariePas encore d'évaluation

- A-level Maths Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsD'EverandA-level Maths Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (8)

- A Mathematician's Lament: How School Cheats Us Out of Our Most Fascinating and Imaginative Art FormD'EverandA Mathematician's Lament: How School Cheats Us Out of Our Most Fascinating and Imaginative Art FormÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)